CHAPTER 14

LITTLE FOOT

IN THE POST-APARTHEID era, South Africa joined in the run of discoveries, opening up new vistas not only on human ancestors but on modern humans. Throughout the apartheid era, while South Africa was shunned by the rest of the world, South African palaeoanthropologists and palaeontologists had persevered with their research, turning Sterkfontein and Swartkrans into the two richest cave sites in the world. By 1994, Sterkfontein alone had yielded more than 700 australopithecine specimens—males and females, infants, children, adolescents and adults—ranging in age from 3 million years to less than 1 million years. But it was a piece of brilliant detective work in the post-apartheid era that led to the most spectacular discovery of all.

In 1994, Ron Clarke, the field director at Sterkfontein, was searching through boxes of fossil animal bones collected previously from a deep underground cavern known as the Silberberg Grotto when he found several hominid foot bones among the jumble of remains that had been overlooked. The fossils had been chiselled out fourteen years before from breccia blocks originally blasted out from the lowest levels of the Silberberg Grotto by lime workers in the 1920s and 1930s.

Clarke was already renowned in the trade for his exceptional skills as a palaeontologist. Born in England in 1944, he had worked for six years as an assistant to Louis Leakey, displaying a particular talent for reconstructing hominid fossils. He had also helped Mary Leakey excavate the Laetoli footprints. He had been in charge of excavations at Sterkfontein since 1991.

Examining the bones, Clarke concluded that four of them belonged to the left foot of an Australopithecus. The bones revealed apelike as well as humanlike characteristics, indicating that the australopithecine had been both bipedal and prehensile, with a grasping tree-climbing capability, spending time in the trees as well as on the ground. Even on their own, the four conjoining bones represented a highly significant find; they were estimated to date back more than 3 million years, making them the oldest hominid discovery yet made in South Africa. In his initial report, Clarke speculated that the australopithecine had fallen down a narrow shaft into the underground cave system and died there, along with a variety of animals. Because the bones were so small, Phillip Tobias proposed naming the specimen ‘Little Foot’.

Three years later, in May 1997, Clarke happened to open a cupboard in the hominid strong room at the Witwatersrand Medical School and noticed a box labelled ‘Cercopithecoids’, containing monkey fossils taken from the Silberberg Grotto. Opening the box, he immediately spotted through the plastic of a polythene bag ‘a tell-tale white bone’ belonging to a hominid and, upon examining it, realised that it fitted with one of the foot bones of Little Foot. Then he found three more foot bones of Little Foot in the same box.

One week later, looking through the contents of another bag, he found what proved to be a vital clue in the chain of events that followed: the slightly damaged fragment of a hominid tibia—the lower leg bone—with an oblique break just above the ankle that looked as if it could have been caused by miners’ blasting. Searching for more fragments of the same tibia, Clarke retrieved—from a bag labelled bovid (antelope) tibiae—a hominid tibia shaft with the distal end intact. This second piece of tibia turned out to fit perfectly with the other bones of the left foot of Little Foot.

Then Clarke realised that the first piece of tibia he had found came from the right leg of the same individual. He remembered finding a small foot bone in the 1994 box which, at the time, he had not been able to match with the other left foot bones. ‘When I looked at it again, I found that it was a hominid bone from the right foot, a mirror image of one of the newly discovered bones of the left foot’.

In all, Clarke had accumulated twelve foot and lower leg bones from a single individual. The conclusion he reached was crucial: ‘The fact that we now had foot and leg bones of both sides of one individual meant that the whole skeleton had to be there embedded in the breccia of that lower cave, the Silberberg Grotto’.

Clarke made a cast of the right tibia that had been broken off at an oblique angle and sent two of the Sterkfontein preparators, Nkwane Molefe and Stephen Motsumi, to look for a matching section of bone in the exposed breccia surfaces of the Silberberg Grotto. ‘The task I set them was like looking for a needle in a haystack’, recalled Clarke.

On 2 July 1997, Molefe and Motsumi began their search. The area of search included the walls, floor and ceiling. The surfaces were damp and covered in mud. The only light came from their hand-held torches. Yet on the second day they found an exact match for the cast in the side of a long slope of hard breccia. ‘The fit was perfect despite the bone having been blasted apart by lime workers sixty-five or more years previously’, said Clarke. ‘I knew then that, encased in that steep slope of ancient cave infill, we would uncover something that palaeoanthropologists had wanted for so long—a complete skeleton of Australopithecus’.

Using hand-held lamps, Clarke, Molefe and Motsumi began to chisel away carefully at the concrete-like breccia. By May 1998, they had uncovered the lower legs. But then, to their consternation, for month after month, they found nothing more. Clarke eventually deduced that the upper part of the body had collapsed into a lower cavity and had been sealed over with thick stalagmite. He selected an area of stalagmite for Motsumi to work on. The next day, Motsumi made a direct hit on pieces of bone that turned out to be the back of a lower jaw and the end of an upper arm bone. Clarke cautiously chipped away more of the rock. ‘The glint of tooth enamel sent a shiver down my spine. It was an upper molar which, together with the lower jaw, told us that we had located the skull’.

Further chiselling revealed that the australopithecine lay on its back on a slope with its left arm extended above its head, its right arm by its side and its legs crossed. The skull was complete, with only some minor cracking and displacement. The skeleton suggested it was an adult, about four feet tall, aged by palaeomagnetic dating as 3.3 million years old. Of particular significance was the discovery of a perfectly preserved hand. It was shaped like that of a modern human hand in proportion, but much more muscular, with a short palm, a long thumb and relatively short fingers. ‘Such a hand with a long and very muscular opposable thumb had apparently evolved in our ancestors for the purpose of firmly grasping branches during tree-climbing’, Clarke explained. ‘This, together with the almost equal arm and leg lengths and the slightly opposable big toe, is consistent with a human ancestor that climbed cautiously in trees’.

He contrasted the australopithecine’s arms and hands with those of modern apes. Modern apes possess long arms and long hands, with long palms, long fingers and short thumbs, developed so that they can suspend themselves beneath branches and move by arm-swinging from branch to branch. When walking on the ground, they use their long arms as supports and walk on their knuckles. By comparison, human ancestors like australopithecines never went through a knuckle-walking stage, but instead retained a primitive hand that was specialised only in its opposable thumb for branch-grasping.

‘It was this long opposable thumb and relatively short palm and fingers that provide the necessary manual ability for tool-use and toolmaking’, said Clarke. ‘It is the combination of this hand and the large complex brain that has enabled humans to develop into the only advanced cultural animal on earth’.

The cave systems in the Sterkfontein area continued to yield spectacular finds. In 2008, a research team led by Lee Berger, a palaeontologist at the University of the Witwatersrand, discovered the first of four fossilised skeletons in a pitlike excavation at Malapa, once part of an ancient underground cave system about 150 feet deep. The Malapa fossils—two adult females, an adolescent boy and an infant—were found within a few feet of each other, suggesting they had died at the same time or soon after one another. The theory was that they had probably died after falling or climbing down a vertical shaft leading to the underground cave system. Within days of their death, a sudden rainstorm and mudflow had washed their bodies—along with the bodies of sabre-toothed cats, hyenas, wild dogs and horses—into a deeper, waterlogged recess where they were encased in calcified rock.

The fossils were dated about 1.9 million years old. Living on the cusp of the emergence of Homo, they possessed a mixture of features: Some were modern, with small teeth, long legs, projecting noses, advanced pelvises; others were archaic, with long arms and small brains. Berger’s team decided they should be assigned as australopithecines rather than to Homo and gave them the name Australopithecus sediba—a Sesotho word meaning ‘fountain’ or ‘wellspring’.

Announcing the finds in 2010, Berger followed the long tradition among palaeontologists of making grand pronouncements about their field discoveries. ‘We do feel that possibly sediba might be the Rosetta Stone for defining for the first time just what the genus Homo is’, he said.

Mary Leakey, seen here at Laetoli at the end of a trail of hominid footprints fossilised in volcanic ash. The trail dates from 3.6 million years ago and shows that hominids had acquired the upright, bipedal, free-striding gait of modern humans by that time.

A single adult footprint from the trail at Laetoli. The footprints show a well developed arch to the foot and no divergence of the big toe.

Mary Leakey at work with the American palaeoanthropologist Tim White during excavations at Laetoli in 1978.

Donald Johanson and Tim White announce the naming of a new hominid species Australopitchecus afarensis in 1979, provoking a furious controversy.

Proconsul africanus: The reconstructed skull of a Miocene era primate discovered at Rusinga Island, Kenya.

The Taung child skull—Australopithecus africanus—discovered in 1924.

An Australopithecus robustus skull discovered at Swartkrans, South Africa, in 1949.

Nutcracker Man, or Zinjanthropus boisei, a robust australopithecine discovered at Olduvai by Mary Leakey in 1959.

A Homo habilis skull found in East Turkana, Kenya, in 1973.

A collection of hominid fossil skulls, together with femur and tibia fragments, found at East Turkana. The skulls are: a Homo habilis specimen known as 1470 after its classification number (centre); Australopithecus africanus (bottom); and Australopithecus robustus boisei (top). These three hominid species were found among deposits that showed they lived contemporaneously, approximately 1.5 million years ago.

A reconstruction of the skeleton of Lucy—Australopithecus afarensis—discovered at Hadar, Ethiopia, in 1974.

A reconstruction of Lucy’s head.

Elisabeth Vrba, a South Africa–born palaeontologist who discovered evidence of dramatic evolutionary change occurring 2.5 million years ago while studying the fossil record of African antelopes.

Yves Coppens, a French palaeoanthropologist involved in major discoveries in Ethiopia and Kenya, pictured in 1983.

Martin Pickford and Brigitte Senut with the remains of ‘Millennium Man’, the first major discovery of the 21st century, which they subsequently named Orrorin tugenensis.

Ron Clarke, a British-born palaeontologist, pictured alongside Little Foot, a Sterkfontein australopithecine which he discovered after a brilliant piece of detective work.

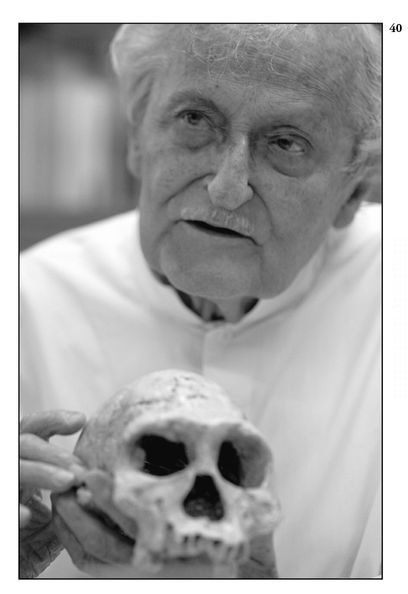

Phillip Tobias, a South African scientist, renowned for his work at Sterkfontein and other southern African sites, pictured in 2006 at the age of eighty.

French palaeontologist Michel Brunet with the 7 million years-old Toumaï skull from Sahara.

An engraved ochre tablet found at Blombos Cave, South Africa, dating back about 75,000 years ago, evidence of early artistic endeavour from Africa.