CHAPTER 1

A Great Divergence?

Kori Schake and Jim Mattis

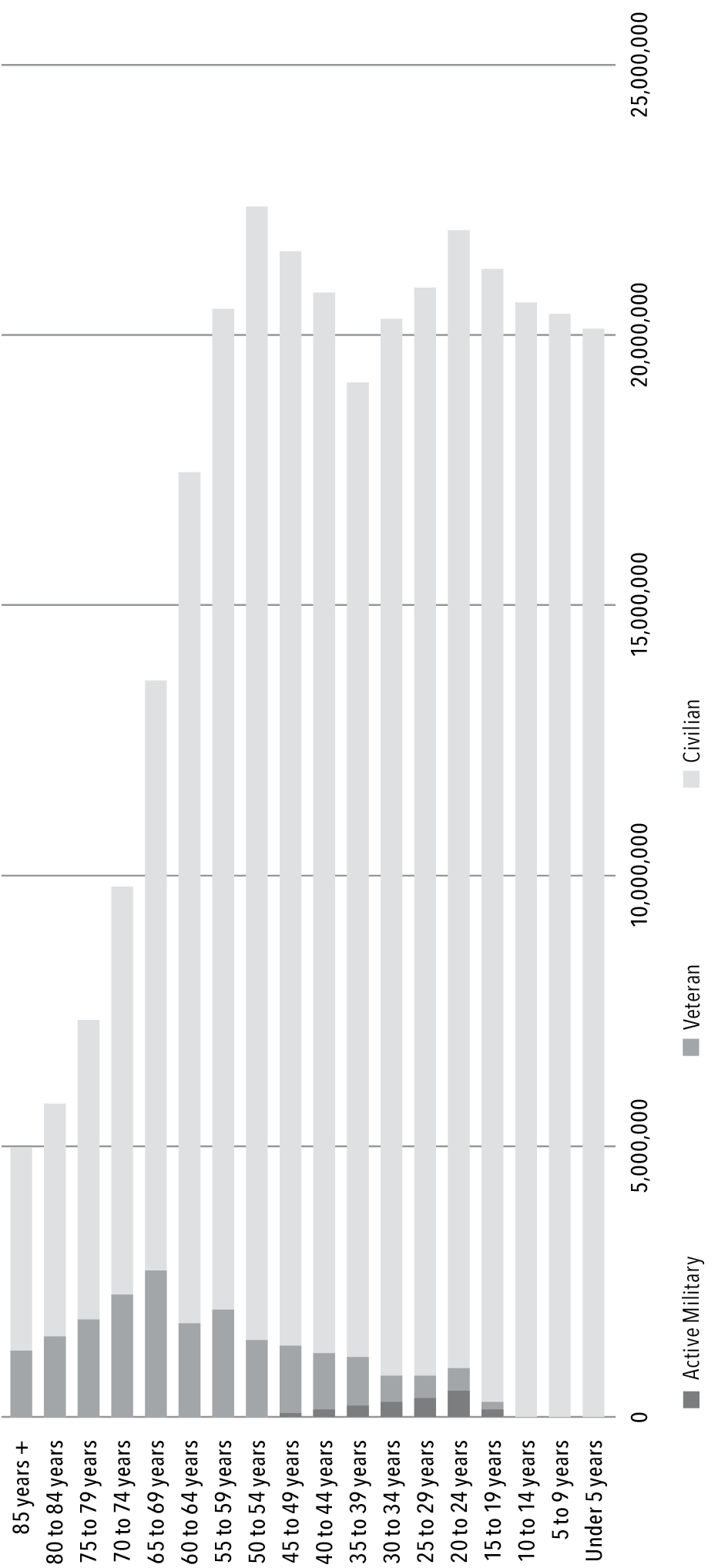

We initiated this project out of curiosity about whether, after forty years of an all-volunteer force, a small force relative to our overall population, and twelve years of continuous warfare, the American public was losing connection to its military. Our concern was not loss of connection in the sense that preoccupies academic experts on civil-military relations in the United States—a military insubordinate to civilian control. We saw scant evidence of that in either our policymaking or military experience. Rather, with less than one half of one percent of the American public currently serving in our military (see figure 1.1) and with the high pace of deployments for significant elements of our fighting forces, we were interested in the cumulative effect of having a military at war when the broad swathe of American society is largely unaffected. Whether or not the different experiences of our military and the broader society amount to a “gap” and whether such a gap is adequately defined seemed worthy areas to delve into.

FIGURE 1.1 United States Civil-Military Population Pyramid

Courtesy of Tim Kane. (Data from United States Census Bureau, “Current Population Survey,” 2012, http://www.census.gov/population/age/, http://www.census.gov/hhes/veterans/data/, and from Defense Manpower Data Center, 2014 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community, 2014, http://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2014-Demographics-Report.pdf, p. 35.)

Source: Tim Kane, The Hoover Institution, based on US Census, ACS, and DMDC (most recent data as of 2015.

The untethering of our military from our society could be damaging to both in many ways. Some thought that our civilian society would become perhaps more willing to engage in wars and certainly more hardened to the costs of warfare from which they have the luxury of being insulated. Anecdotes indicated that public inexperience with veterans could complicate their reintegration into society, even cause them to be perceived as a threat to the broader society. With little experience of warfare in the general population, the public may have scant appreciation for what is needed to win our wars or become contemptuous of the military virtues necessary for winning on the battlefield when those virtues are out of synch with the values of our civil society. Elected political leaders without military expertise may have trouble crafting strategies for the successful conduct of our wars. The military could even come to consider itself a society apart, different from, and more virtuous than, the people they commit themselves to protecting, like praetorian guards at the bacchanalia, as one soldier described it. Or our military could begin to feel that society “owes them something,” fostering entitlement attitudes that would chip away at the culture essential to retaining warriors in our military forces. We were concerned above all about suggestions that the rest of society has simply become apathetic to the issues that dominate the consciousness of those who have been putting their lives on the line for the rest of us in the wars our country is fighting.

While major surveys of public attitudes occasionally focus series on veterans’ issues and include some questioning in these areas, we were surprised at the dearth of systematic data or quantifiable indicators to gird analysis about the American public’s understanding of, and relationship to, its military. After two extensive polls and cross-disciplinary exploration, we are greatly relieved to say that the concern about the American public losing connection to its military was not substantiated by research conducted for this project. The common perception of divergence is wrong. Public opinion surveys conducted as part of this study strongly suggest that while the American public is not knowledgeable about military issues, its judgment is fundamentally sound, and its concern is unabated for the soldiers, sailors, airmen, coastguardsmen, and Marines who fight the nation’s wars.

Whatever they think of the wars our country is fighting, Americans no longer blame their military as many did during the Vietnam War. The enormous respect Americans have for our military is obvious in ways large and small throughout society: the near-universal convention of thanking men and women in uniform for their service; the now-standard practice of tributes to our military during major sporting events; airlines’ policy of boarding military passengers first (without apparent exasperation by other travelers); and—especially—the overwhelming support in Congress for increasing military pay and benefits, even when the military services themselves would like to curtail the rate of growth. No one gets elected in America running against the troops. Foreign troops serving in America are often amazed at the affection Americans demonstrate for our military personnel.

In this way, the broader society reflects the distinction prevalent in the military itself between personal judgments about a war and the commitment to fighting it. Choosing war is the business of elected politicians in America; fighting war is the business of our military. The sturdiness of this principle on both the civilian and military sides of the equation goes a long way to explaining the affection Americans now have for their military, even though less than 16 percent of Americans served or had a family member serve since 9/11.

The American military’s continuing function as a conveyor belt into the middle class is another strong source of public affection. Strong majorities of both the public and elites consider the American military one of the few remaining reliable means of economic advancement, especially for minorities and the poor. As an institution, it is also considered fairer than virtually any other: it clearly defines and rewards merit. Our research revealed that these long-standing conventions still have powerful resonance with the American public.

The surveys identified, however, many gaps between the American public and its military. We wondered whether some of these gaps make public support for the military broad but shallow. In other words, support for the military is an easy social convention because it demands little from the broader populace. We also explored whether some gaps could in time erode important elements of America’s beneficial civil-military relationship. Moreover, some operant gaps appear not between civilians and the military but between civilians and civilian elites or between civilians and governmental elites, with concomitant effects for the military.

Research Questions

Reviewing the literature on civil-military relations and utilizing our experience in defense policy and the military, respectively, we identified several initial concerns for exploration in the surveys.

Ignorance

Does the public have a basic working knowledge of the military? Does their lack of knowledge lead to worrisome misconceptions—for example, that all veterans suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), making them potentially dangerous? Knowledge differences could also affect recruitment and make the public less empathetic about the demands of military life. Does the differential level of knowledge cause the public to be too deferential to military views or cause the public to believe the military is insufficiently deferential to civilians on issues properly decided by suits rather than uniforms?

Public ignorance could also affect the choices political leaders make about warfare: whether to use military force at all, whether to adopt an approach of overwhelming or incremental force, how much political capital to expend on war efforts, whether they face political reversals for escalating costs or failure to achieve their war aims. It can also lead to dramatic and rapid collapses in public support for war efforts. The relationship is interactive: the less informed the public, the greater latitude governmental elites have to avoid electoral consequences for the material and human cost of strategic failure and the more likely public support is to be erratic and quickly eroded.

Strategy Differences

Is there a different approach to making strategy as the result of fewer military veterans’ involvement at high civilian policymaking levels? Before 9/11, it was believed that civilians have a more relaxed view of threats than does the military; since 9/11, scholarly concern has shifted to the way civilians can be too willing to use military force while policymakers focus on civilian opinion and may not understand how to use military force effectively.

Several studies suggest a “veteran advantage” in the making of policy; namely, that veterans are believed to be more hesitant to use military force than civilians. Civilians tend to overstate what military force can achieve, to assume a wider margin for error than those with knowledge and experience from military service, and to lack the analytic discipline essential to developing clear and achievable war aims. Moreover, in a political culture with wide acceptance for the use of military force, veterans are better positioned politically to withstand public pressure favoring it. But military leaders often try to leach the politics out of political decision making in order to better analyze problems and develop strategy; this can lead to “perfect” solutions impractical for consideration by elected officials whose portfolios are broader than the military mandate alone.

Isolation

Because of its smaller size and how little the wars affect the general public, is the military growing more distant from society? Some of the impediments to routine interaction between civilians and the military are the result of budget or operational choices, such as consolidating military forces on fewer larger bases. Some are a consequence of base security or convenience. The result is seclusion for many military families from nearby support in the broader community and less understanding of the demands of military life by civilians.

Most civilians, for example, would have little idea of how to comfort a military family grieving a loss—something that was a much more common experience when our military was larger and service compulsory. Many well-intentioned Americans cannot even find a thread of conversation when discussing military service with a veteran other than asking about PTSD or sexual harassment in the case of female vets. This is potentially a two-way problem: veterans may not want to dwell on their wartime experiences or let such experiences define them in the eyes of society.

Cultural Differences

There is a fundamental difference between military rank structure and the egalitarian culture of America. This sometimes leads civilians without personal familiarity with the military to believe military service is “only about following orders.” There is also among some civilians the temptation to treat warfare as just another arena of politics, with public indifference giving latitude for the imposition of social choices—conservative or progressive—uninformed by the grim exigencies and atavistic demands of warfare. This can translate into a perceived lack of respect by civilians in a military culture steeped in respect.

The culture gap can also lead to difficulties in military recruitment and the reintegration of veterans. Is the public sensitive to the military’s concern that too great a focus on benefits may not bring into the military the types of people the military believes it needs? It can also lead to service members and their families undervaluing the well-intentioned gestures civilians make toward them (for example, yellow ribbons or verbal thank-yous), mistaking unfamiliarity for empty tokenism.

The perception is widespread in the military that civilians are insensitive to its culture—more than insensitive: intolerant. Is our military ideologically and socially out of step with the rest of society? Does the public appreciate that values and practices in the military considered old-fashioned and even out of step with the broader society are considered by many in the military to be integral to their fighting functions in defense of that society? Will a progressive society continue to invest in and connect itself to a military whose requirements for success on the battlefield demand attributes fundamentally at odds with those of the society it protects? If not, is a war-winning military sustainable in a society in which war’s gruesome realities must be reconciled to an operant degree with the larger society’s human aspirations?

Undermining Military Effectiveness

Many of the policies civilians are most eager to change about the military are perceived by civilians as social in nature: the inclusion of women in the infantry, and allowing homosexuals and transgender people to serve openly in America’s military forces, for example. The public may perceive them as civil rights issues; the military by and large does not. In fact, there is concern in the military both about distrust among junior ranks toward their seniors for not defending the military’s prerogatives and about losing those people we most need to draw to and keep in our fighting ranks. Are civilians intruding into healthy and necessary functional practices by the military? Are there social pressures on the military to adopt a victim mentality? How committed is the public at large to effecting these changes? Do they perceive trade-offs with military effectiveness? Is the public open to military arguments or do gaps in understanding prevent the arguments from gaining traction? Are uninformed civilian leaders viewing military leaders in political terms, leading them to dismiss as partisan sound military advice or to vet military leaders by their perceived politics rather than military qualifications?

Changed Civil-Military Relationships

Far down in our list is the issue that predominates in academic inquiry: diminishing loyalty to civilian leaders. We see little evidence of this in today’s American military, but serious people worry about commitment on the part of the military to upholding the principle that elected leaders have a “right to be wrong”—to go against military advice because civilian leaders have to aggregate societal preferences and make decisions about how much to commit to war efforts.

It is currently more common to hear complaints that the military is too deferential to its political leadership, but might there eventually develop a counterpressure in the military to insist rather than advise? Are changes in public attitudes about elected leaders eroding restraints that the professional ethos of the American military imposes on itself? These pressures could push the military into politicized roles, something it is deeply uncomfortable with, or cause cynicism about civilians for hiding behind the military to avoid taking responsibility for their political choices. Perceptions of politicization by civilian leaders can also lead to vetting military nominees for political pliancy.

The Grief Gap

The American military feels its casualties deeply and has rituals and ceremonies to grieve losses and bind military units and communities together. The public is largely unaffected by deaths and wounds from the wars, and we have few public rituals beyond Veterans Day and Memorial Day to involve the public and pull the military into the broader society in times of grief. This can lead to a perception by the military that broader society does not understand their losses. There also seems to be an atrophying in the broader society of understanding and willingness to bridge the gap of grief and meaningfully engage Gold Star families. What had been a more common experience of loss in previous wars now tends to be an isolating experience for military families. Are there practices that can be promulgated throughout society, as has been the practice of routinely thanking our military for its service, to better get our civilian arms around our military in times of loss?

Military Entitlement

Another azimuth of potential concern is whether civilian society has begun to think about the American military as, and the military has come to behave like, just another interest group in our national political scrum. Is there tension between a self-regarding “only 1 percent serve” attitude among the military and a “you signed up for this” attitude among the public? Are choices by the military leadership about when and how to engage in public debate over spending or policy issues delegitimizing? Is the political activism of veterans’ organizations and retired military officers shading perceptions of the active-duty military? Will the national indebtedness lead to trade-offs between public beneficiaries that stoke resentment about veterans’ preferences? All of these things could portend a diminished demonstration of respect for the military by American society. And while it would take a cataclysmic collapse to bring regard for the military down to the levels of public distrust encountered by every other organ of the federal government, this diminishment would still represent a significant change in the relationship the American public has had with its military since the Vietnam nadir.

Civilian-Military versus Elite Civilian Categories

There is a widespread (although possibly outdated) perception that our soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, coastguardsmen, and their families tend to be more religious and hold more politically conservative views than the rest of society. This tendency may also be true of the general population of our country as compared with elites. Which of the many ways to define elite—advanced education, high income, skilled profession, community stature, policy influence—have relevance for civil-military issues? Do elites accurately understand public attitudes about the issues? Are elites of some stripes less appreciative of martial values than the rest of civilian society?

The public may share the military’s views but not know, or care, whether the military is allowed to preserve them. Are elites responding to public pressure for social change in the military? Or are they seeking to utilize the military as a laboratory for social change, capitalizing on the lack of connection between the military and general public and making the military lead (instead of follow) the broader society’s trends? Sensing that the military speaks for the public could lead elites to distrust military advice, or the advisors themselves, for having a court of appeal in the public if their advice is rejected by elected leaders.

Nonmilitary Purposes

Americans like our military partly because it is good at its job. Does that incline policymakers to utilize the military rather than other national tools to achieve their objectives? Many of our current national security challenges require developing cultural expertise about societies becoming threats to us because of their weakness—not obviously a military task. The past decade has been a long slog of mastering (or remastering) counterinsurgency, and inherently civilian functions have migrated to the military because as a country we keep selecting strategies that rely on “whole of government” capacities our government manifestly lacks. Put another way, if only our intelligence agencies and military are organized to compete in a globalized world, do our national leaders fail to use traditional diplomacy and instead reach too often for the military instrument?

Has the nature of contemporary national security threats seemed too elusive for military force to effectively combat? Has observing our military at war for the past decade affected public confidence in its central obligation of winning the nation’s wars? Has the tendency among elected officials to talk of all veterans as though they are disabled and to represent all trauma as weakening rather than strengthening diminished public confidence in our fighting forces?

Familiarity

Lastly, we were interested in whether the panoply of civil-military issues could be addressed by fostering simple familiarity. Earlier studies have found the strongest correlate of shared civilian and military attitudes to be personally knowing someone who is or has been in military service. With the smaller size and professionalization of our military is that familiarity being lost? If so, does that lead to “brittle and shallow” public support? Does knowing someone in the military make the public more or less likely to give the benefit of the doubt on issues where the public is not fully informed? Is the American system of national security policymaking, designed for dialectic discussion at high levels between elected leaders and the military, so brittle that it requires heroic effort to function?

Methodology

We did not address all of these questions, but they provided the universe of inquiry in which we thought about the issues, developed polling questions to probe for public attitudes, and looked for interesting answers among the data. Many of them touch on related phenomena.

Most of these issues were identified in the seminal Triangle Institute for Security Studies (TISS) project of 1998, which, it turns out, is the last systematic research about civil-military relations conducted on a large scale. Much of our understanding was shaped by it, and many of our survey questions were cribbed directly from it. This pilferage not only represents the highest academic compliment but also was intended to provide a second set of data points on these issues following over a decade of war with our all-volunteer military—a first in our history. We anticipate future studies will continue this practice so that trend analysis will become possible. It would be a great benefit to scholarship for such data collection to become routine across decades.

This study attempts to accomplish five objectives:

• collect data on American public attitudes toward the military;

• identify those gaps between civilian and military attitudes on issues central to the military profession and the professionalism of our military;

• determine which if any of these gaps are problematic for sustaining the traditionally strong bonds between the American military and its broader public;

• analyze whether any problematic gaps are amenable to remediation by policy means; and

• assess potential solutions.

Much of the debate about civil-military issues is driven by anecdotal or impressionistic evidence. Experiential data is valid but may not be generalizable. We sought the ability to determine whether the concerns were systemic. In order to explore these questions, we designed and conducted two extensive surveys of public attitudes. Public opinion research is, of course, not definitive, and we can only make limited claims on the basis of two studies. But there is no knowing what the public thinks without asking the public, and we wanted to start the exploration with at least some data on which to base analyses by a cadre of thinkers.

We attempted across the two surveys to ask questions differently in order to get some sense of the degree to which responses were sensitive to wording. In developing the surveys we were guided by the experts at the internet-based market research firm YouGov. We began with a baseline survey, to identify general issues, train our judgment on the tradecraft of survey design, and gauge whether potentially interesting attitudes might merit further and more detailed research. Our initial, baseline survey suggested that surprising and interesting variations may exist between elites and the general public on these issues. We designed the second, much larger survey to test that proposition across a wide array of substantive issues.

Coming up with a robust definition of “elite” proves surprisingly difficult. Separating wealth from political affiliation, and in some cases profession from political affiliation, turns out to be tricky. The Triangle study from 1998—far and away the most important survey of public attitudes—was criticized by Andrew Kohut of the Pew Research Center for a selection bias that, he believed, called some of the study conclusions into question. The wizards at YouGov puzzled over this for us and developed a methodology, described thus via email, that we hope will prove useful:

The dataset includes 500 interviews with a sample of elites designed to represent opinion leaders in 10 professional areas of expertise—media, business and finance, state and local government, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), think tanks and academia, religious organizations, and congressional staff. The elite sample was randomly drawn from leaders in the sectors of business and finance, academia, and religious organization using publicly available lists of leaders. Academics were selected from members of the National Academy of Sciences, executives from the largest 500 US companies ranked by total annual revenue as of June 1 of the current year, journalists from the 2013 list of best state-based political reports, religious organizations from a database of religious institutions compiled from the Pluralism Project at Harvard University. Congressional staff, NGO leaders, and think tank staff were recruited via YouGov’s DC Insider recruiter.

We sought out experts to apply their perspectives to the YouGov data. Our sorting criteria for authors was simple: we chose the people we learn from. We wanted a host of scholars to sort out what it all meant, for, as with picking raspberries, we would miss a lot if the data were examined from a single perspective. Rosa Brooks, Georgetown University law professor, defense policy analyst, and military spouse probes the paradoxes of public attitudes. Mackubin Thomas Owens, editor of Orbis and author of US Civil-Military Relations after 9/11, considers how the data challenge or reaffirm his thinking. Peter Feaver, Duke University professor of political science who ran the 1998 Triangle study, Major Jim Golby, and Lindsay Cohn explore the differences in findings between that study and our data. Benjamin Wittes, founder of the Lawfare blog, and Cody Poplin of the Brookings Institution examine perceptions of the military justice system. Nadia Schadlow, from the Smith-Richardson Foundation, reflects on executive branch difficulties putting military force into broad and effective national security strategies. Tom Donnelly, director of the Marion Ware Center for Defense Studies at the American Enterprise Institute, gives his insights on how changing public attitudes affect Congressional action in defense policy. Tod Lindberg, Hoover fellow and author of The Heroic Heart: Greatness Ancient and Modern (2015), looks across the political spectrum for similarities and differences in our cultural attitudes about the military. Matthew Colford and A. J. Sugarman, recent Stanford graduates now both working in policy jobs in Washington, suggest ways to better connect young Americans with the military. Jim Hake, founder and CEO of the nongovernmental organization Spirit of America, also picks up the theme of how to better connect Americans to the nation’s war efforts. In concluding, we try to sift through the issue of whether the public attitudes displayed in the surveys conducted for this project are consistent with preserving dominant military power for the United States.

Main Findings

Rosa Brooks explores a series of paradoxes in American attitudes toward their military: enthusiasm for our military coupled with ignorance about it; mistrust with awe; belief that our military is the world’s best with opinion that it is incapable of addressing today’s most pressing threats; appreciation for our military’s professionalism with decrying of its institutional differences from broader civilian society. She perceives a “pernicious gap between elite civilian political leaders and elite military leaders: a gap of knowledge, and a gap of trust,” arguing that “if we want a military that is strong, capable and responsive to America’s changing needs, we will need to rethink many of our most basic assumptions about the military and its role.”

Mackubin Thomas Owens gives an overview of civil-military frictions in America, emphasizing that current levels fall well within historical norms and that the bargain between the American people, the president, the Congress, and their military is always being renegotiated. He illustrates that our system of military subordination to civilian control with wide latitude for military input in advance of policy decisions relies fundamentally on mutual trust between civilian officials and military leaders. He believes the YouGov data show a worrisome trend toward distrust of the military among elites—especially self-described “very liberal” elites—as well as a growing political partisanship in the military that augur greater civil-military friction. Moreover, he considers the uninformed public gives political leaders wider latitude to impose “transmutation” of progressive cultural values over the functional imperatives of the military for success on the battlefield.

Jim Golby, Lindsay Cohn, and Peter Feaver explore the ways fighting extended wars our all-volunteer force was not designed for, and without the other resources of a full wartime mobilization of society, have affected civil-military relations since the seminal 1998 Triangle study. They find a striking continuity in public attitudes and are reassured the all-volunteer force has not become dangerously isolated from the rest of society. They do identify a large increase in civilian ignorance or apathy about military issues and also in civilian deference to the military on conduct of the wars, which they consider may be connected to decline in trust of civilian leadership. They see in the YouGov data a disturbing public acceptance of norms for military behavior improper in the American civil-military model, belief that the military has different values than the rest of society, and decline in familiarity with our military. They offer several recommendations to shore up important elements of American civil-military relations, including better scholar and journalist policing of politicization of the military by politicians and veterans’ groups, and caution against policy remediations such as the draft, which they consider “a cure that is worse then the disease.”

Benjamin Wittes and Cody Poplin emphasize the volatility and contradictions in public attitudes about the wars our country is fighting, noting that, while pessimism Americans have about the policies being pursued stokes support for stronger actions, the public’s ignorance about military issues precludes them from developing stable views on the complex issues of current conflicts where military operations are tightly integrated with issues more often associated with law enforcement and justice. They worry that this combination will lead to ineffectual counterterrorism policies, policies that symbolize toughness without achieving lasting effects, unless political leaders engage the public more substantively. They also highlight the fact that, while Americans generally support the military having different standards from those in our broader society, there is significant public opposition to specific applications by the military of those different standards.

Nadia Schadlow suggests that public attitudes are much less a constraint on the making of strategy than civilian leaders attest. She emphasizes that engagement of the public has substantial effects on public attitudes, especially given the high frequency of “don’t know” responses in the YouGov surveys. The nature of the war, its anticipated costs, strong civil-military leadership, and the coherence of strategy weigh heavily in public consideration. By failing to engage the public on its strategy, civilian leaders may be creating the constraint of public disapproval that they argue is determining their policy choice.

Thomas Donnelly believes that, while scholars of civil-military relations advocate energetic civilian management of military policy—and politicians even believe they practice that supreme command—in reality, we have a rigid distinction between military and civilian spheres of competence and high levels of civil-military tension that are debilitating to our national security policies. He argues for a Janowitzian approach, with greater blending of civilian and military perspectives. Donnelly also believes the familiarity gap between civilians and the military has led to pity rather than respect for the difficulties service families undergo on our behalf. He concludes, “It’s only a little hyperbolic to conclude that some Americans—those who feel most removed from military life—see the service as an experience leading to pathological behavior.”

Tod Lindberg is, by contrast, sanguine about the state of civil-military relations, drawing from survey data that a high level of trust in the military is “a bedrock component of the American social compact.” He emphasizes the distinction of self-described “very liberal” Americans in their attitudes toward the military as compared with those in every other political category, for example in debates over the movie American Sniper and with regard to their confidence that the military can be made more like the rest of society without negative repercussions in their ability to win our nation’s wars. He notes that the 4.8 percent of Americans who hold these views are considerably fewer than often have held a skeptical view of our military yet they wield a disproportionate cultural influence that can alienate civilians unfamiliar with the military, and that can often impose policy changes on social issues within our military.

Matthew Colford and A. J. Sugarman modeled a greater civilian effort to connect with our military, designing and teaching a course on civil-military relations while still undergraduate students at Stanford University. They point out that “young Americans between 18 and 29 have made the transition into adulthood during the single longest period of continuous war in American history,” and YouGov survey data illustrate that their attitudes are indeed different from their elders. Colford and Sugarman note that young Americans’ attitudes toward the military actually accord most closely with those over 65, the last generation to have experienced our country being at war for an extended duration. But given the smaller size of our contemporary American military and policies by universities that still in effect restrict ROTC programs, young Americans are significantly less informed. Colford and Sugarman offer several suggestions for ways the military could interact more with young Americans and open itself up to greater involvement by young Americans.

While most scholars of civil-military relations place the burden of reconnecting the civilian and military spheres of American civic life on the military, Jim Hake shows that “the resources and brainpower of our citizens—unfettered by bureaucracy and the inevitable restrictions on the use of taxpayer funds—can have an off-scale impact” on military operations. His chapter describes creating an organization that crowd-funds support to the mission needs of deployed troops, a venture capital model of giving civilian America a participatory role in projects to assist military missions and thereby reconnecting them directly with the war effort and deployed servicemen and women.

In conclusion, we explore some possible consequences of two themes that emerged strongly for us from the data: public disengagement and the effect of high levels of public support for the military combined with very low levels of trust in elected political leaders. The pervasiveness of “don’t know” responses across the breadth of survey questions indicates a public largely uninformed about military issues. In all but the arena of social issues, the public defers to military judgment—and familiarity with the military tends to erase even this exception. This deference contrasts starkly with the decline in public respect for, and trust in, its elected leaders, which has the potential to shift toward the military the balance of responsibility properly tilted toward elected civilian leaders.

We also reflect on whether American society is becoming so divorced from the requirements for success on the battlefield that not only will we fail to comprehend our military, but we also will be unwilling to endure a military so constituted to protect us. In particular, we are concerned that civilians believe the military can sustain a war-winning force without the values our military inculcates in order to produce success on the battlefield.

Because we believe complacency about military requirements could lead to terrible outcomes for our country, we also venture some recommendations for remediation of this gap in cultural appreciation appropriate in a nation whose military is under civilian control. Most of the weight of these recommendations falls to civilians, not the military. Many of them focus on the responsibility of elected leaders. All of them seek to foster greater familiarity that will ensure our military are braided tightly to our broader society in a manner that will keep alive our experiment in democracy.