Ravi A. Madan and William L. Dahut

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Prostate cancer (CaP) is the most common noncutaneous malignancy and the second most frequent cause of cancer-related mortality in men in the United States; in 2017 there will be an estimated 161,360 men diagnosed with CaP and 26,730 deaths from the disease. A greater than 30% decline in incidence in recent years is likely due to decreased screening. The long-term implications of this remain unknown.

Prostate cancer (CaP) is the most common noncutaneous malignancy and the second most frequent cause of cancer-related mortality in men in the United States; in 2017 there will be an estimated 161,360 men diagnosed with CaP and 26,730 deaths from the disease. A greater than 30% decline in incidence in recent years is likely due to decreased screening. The long-term implications of this remain unknown.

The frequency of clinically aggressive disease varies geographically, but the frequency of occult tumors does not, suggesting the influence of environmental factors in the etiology of CaP.

The frequency of clinically aggressive disease varies geographically, but the frequency of occult tumors does not, suggesting the influence of environmental factors in the etiology of CaP.

RISK FACTORS

Age: Risk increases progressively with age, with about 70% of cases in men over the age of 65.

Age: Risk increases progressively with age, with about 70% of cases in men over the age of 65.

Family history: Risk increases 2-fold with a first-degree relative diagnosed with CaP, 5-fold with two first-degree relatives.

Family history: Risk increases 2-fold with a first-degree relative diagnosed with CaP, 5-fold with two first-degree relatives.

Race: In the United States, incidence is highest among African Americans, followed by whites, then Asians. African-American men are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced disease and have a greater than 2-fold risk of death from the disease.

Race: In the United States, incidence is highest among African Americans, followed by whites, then Asians. African-American men are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced disease and have a greater than 2-fold risk of death from the disease.

Geography: Risk is lowest in Asia, high in Scandinavia and the United States.

Geography: Risk is lowest in Asia, high in Scandinavia and the United States.

Diet: Consumption of red meat and animal fat has been associated with CaP, while eating cruciferous vegetables, soy products, and lycopene-containing tomato products may be protective.

Diet: Consumption of red meat and animal fat has been associated with CaP, while eating cruciferous vegetables, soy products, and lycopene-containing tomato products may be protective.

Genetic Drivers: Emerging understanding about the underlying genetics of prostate cancer suggests that androgen receptor mutations drive the majority of advanced (metastatic, castration resistant) disease, but 20% to 30% of cases may have underlying DNA damage repair mutations. In addition, an analysis of 692 men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer found that nearly 12% had inherited (germline) mutations in the DNA repair pathway. Retrospective data suggest that these defects in DNA repair may be prognostic for worse clinical outcomes in men with newly diagnosed disease.

CHEMOPREVENTION TRIALS

5-α Reductase Inhibitors

Two clinical trials have evaluated the ability of 5-α reductase inhibitors to prevent CaP in asymptomatic men older than 50 years, although neither is approved for this purpose.

Two clinical trials have evaluated the ability of 5-α reductase inhibitors to prevent CaP in asymptomatic men older than 50 years, although neither is approved for this purpose.

In the Prostate Cancer Prevention trial, finasteride was compared to placebo in more than 9,000 men. There was a reduction in the incidence of CaP from 24.8% in the placebo arm to 18.4% in the finasteride arm within 7 years (P < 0.001).

In the Prostate Cancer Prevention trial, finasteride was compared to placebo in more than 9,000 men. There was a reduction in the incidence of CaP from 24.8% in the placebo arm to 18.4% in the finasteride arm within 7 years (P < 0.001).

In the REDUCE trial, 8,321 men randomized to receive either dutasteride or placebo. Again, there was a reduction in the incidence of CaP in the treatment arm by 22.8% over the 4-year study period (P < 0.001).

In the REDUCE trial, 8,321 men randomized to receive either dutasteride or placebo. Again, there was a reduction in the incidence of CaP in the treatment arm by 22.8% over the 4-year study period (P < 0.001).

Both of these prevention studies found an increase in the percentage of aggressive tumors (Gleason score 7 to 10) in patients treated with the respective 5-α reductase inhibitors compared to the placebo. Subsequent pathology reviews of prostatectomy specimens did not confirm this increase, indicating potential sampling bias in the biopsies, perhaps due to a preferential reduction in normal versus tumor tissue caused by the effect of the 5-α reductase inhibitors.

Both of these prevention studies found an increase in the percentage of aggressive tumors (Gleason score 7 to 10) in patients treated with the respective 5-α reductase inhibitors compared to the placebo. Subsequent pathology reviews of prostatectomy specimens did not confirm this increase, indicating potential sampling bias in the biopsies, perhaps due to a preferential reduction in normal versus tumor tissue caused by the effect of the 5-α reductase inhibitors.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not endorse either finasteride or dutasteride for the prevention of prostate cancer.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not endorse either finasteride or dutasteride for the prevention of prostate cancer.

SCREENING

Screening for CaP involves testing for levels of PSA and/or DRE. Screening of asymptomatic men is controversial. Debate centers on whether biologically and clinically significant cancers are being detected early enough to reduce mortality or, conversely, whether cancers detected by screening would cause clinically significant disease if left undetected and untreated. Autopsy series have shown that more men die with, rather than from, CaP, and the rate of occult CaP in men in their 80s is approximately 75%.

Screening for CaP involves testing for levels of PSA and/or DRE. Screening of asymptomatic men is controversial. Debate centers on whether biologically and clinically significant cancers are being detected early enough to reduce mortality or, conversely, whether cancers detected by screening would cause clinically significant disease if left undetected and untreated. Autopsy series have shown that more men die with, rather than from, CaP, and the rate of occult CaP in men in their 80s is approximately 75%.

The Prostate, Lung, Colon, and Ovary (PLCO) screening trial and the European Study on Screening for Prostate Cancer are evaluating clinical outcomes based on screening versus no screening. Data from the PLCO trial reveal that the rate of death from CaP was very low and did not differ significantly between subjects assigned to screening (n = 38,340) or no screening (n = 38,343), with nearly 15 years of follow-up. Despite these two large studies the evidence does not clearly support uniform population-based screening practices using PSA.

The Prostate, Lung, Colon, and Ovary (PLCO) screening trial and the European Study on Screening for Prostate Cancer are evaluating clinical outcomes based on screening versus no screening. Data from the PLCO trial reveal that the rate of death from CaP was very low and did not differ significantly between subjects assigned to screening (n = 38,340) or no screening (n = 38,343), with nearly 15 years of follow-up. Despite these two large studies the evidence does not clearly support uniform population-based screening practices using PSA.

Data from the European study suggest that PSA screening was associated with a reduction in the rate of death from CaP by 21% after a median follow-up of 13 years. These data indicate 781 men would need to be screened and 27 additional cases of CaP would need to be treated to prevent one death from CaP. Contamination from PSA screening outside the trial were less likely in Europe and could explain the differences with this study and the PLCO study.

Data from the European study suggest that PSA screening was associated with a reduction in the rate of death from CaP by 21% after a median follow-up of 13 years. These data indicate 781 men would need to be screened and 27 additional cases of CaP would need to be treated to prevent one death from CaP. Contamination from PSA screening outside the trial were less likely in Europe and could explain the differences with this study and the PLCO study.

Controversy surrounds screening recommendations for prostate cancer in the United States. As of 2012, the US Prevention Services Task force recommends against PSA screening.

Controversy surrounds screening recommendations for prostate cancer in the United States. As of 2012, the US Prevention Services Task force recommends against PSA screening.

The American Cancer Society suggests patients make an informed decision about PSA screening after a discussion with their health-care provider. Such decisions should be at age 50 for men who are healthy and expect to live 10 more years, at age 45 for men who are at high risk (African American or those with a first-degree relative having prostate cancer at an age under 65) or 40 for the highest-risk patients (multiple first-degree relatives having prostate cancer at an age under 65).

The American Cancer Society suggests patients make an informed decision about PSA screening after a discussion with their health-care provider. Such decisions should be at age 50 for men who are healthy and expect to live 10 more years, at age 45 for men who are at high risk (African American or those with a first-degree relative having prostate cancer at an age under 65) or 40 for the highest-risk patients (multiple first-degree relatives having prostate cancer at an age under 65).

•Most advocates of screening acknowledge the limited benefits in men who are over 75 years of age or men with less than 10 years of projected survival due to other comorbidities. It is likely that most men who fall in this category will not have their lifespan limited by CaP and thus screening may be unnecessary.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Even with declines in PSA screening in the United States, most men are asymptomatic at diagnosis.

Even with declines in PSA screening in the United States, most men are asymptomatic at diagnosis.

Patients with local or regional disease may be asymptomatic or have lower urinary tract symptoms similar to those of benign prostatic hypertrophy or occasionally hematuria.

Patients with local or regional disease may be asymptomatic or have lower urinary tract symptoms similar to those of benign prostatic hypertrophy or occasionally hematuria.

Symptoms of metastatic disease include bone pain, changes in urination patterns, and weight loss; spinal cord compression is a rare but serious complication of metastatic disease.

Symptoms of metastatic disease include bone pain, changes in urination patterns, and weight loss; spinal cord compression is a rare but serious complication of metastatic disease.

WORKUP AND STAGING

Biopsy

Abnormal PSA and/or DRE is followed by transrectal ultrasound with core biopsy. Historically, a PSA of >4 ng/mL was the threshold for biopsy, but current data suggest that cancers can be seen with lower PSA levels. In recent years a greater emphasis has also been placed on rate of PSA rise as a trigger for biopsy. A negative biopsy should prompt reassessment in 6 months with repeat biopsy as needed.

Abnormal PSA and/or DRE is followed by transrectal ultrasound with core biopsy. Historically, a PSA of >4 ng/mL was the threshold for biopsy, but current data suggest that cancers can be seen with lower PSA levels. In recent years a greater emphasis has also been placed on rate of PSA rise as a trigger for biopsy. A negative biopsy should prompt reassessment in 6 months with repeat biopsy as needed.

There is an evolving role for combining magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound guided prostate biopsy in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. As opposed to random biopsies of the prostate, data from MRI imaging of the prostate is used to identify anatomic regions in the prostate that likely contain tumor. These regions can be deliberately oversampled during the biopsy procedure (informed biopsy) or using software that creates a fusion of the MRI image with real-time ultra sound, a targeted biopsy of the intraprostatic tumor can be done.

There is an evolving role for combining magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound guided prostate biopsy in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. As opposed to random biopsies of the prostate, data from MRI imaging of the prostate is used to identify anatomic regions in the prostate that likely contain tumor. These regions can be deliberately oversampled during the biopsy procedure (informed biopsy) or using software that creates a fusion of the MRI image with real-time ultra sound, a targeted biopsy of the intraprostatic tumor can be done.

Pathology

Ninety-five percent of CaPs are adenocarcinomas. Adenocarcinoma arises in the peripheral zone of the prostate in approximately 70% of patients.

Ninety-five percent of CaPs are adenocarcinomas. Adenocarcinoma arises in the peripheral zone of the prostate in approximately 70% of patients.

Small cell variants of prostate cancer are very rare and characterized by aggressive tumors with increased likelihood to have soft tissue metastasis, especially to the liver. These tumors may be more susceptible to DNA damaging agents (PARP-inhibitors or platinum agents) although randomized data in this population is lacking. It is important to note that adenocarcinoma with “neuroendocrine features” is more common than small cell variants and should be treated primarily as adenocarcinoma.

Small cell variants of prostate cancer are very rare and characterized by aggressive tumors with increased likelihood to have soft tissue metastasis, especially to the liver. These tumors may be more susceptible to DNA damaging agents (PARP-inhibitors or platinum agents) although randomized data in this population is lacking. It is important to note that adenocarcinoma with “neuroendocrine features” is more common than small cell variants and should be treated primarily as adenocarcinoma.

Sarcoma, lymphoma, small cell carcinoma, and transitional carcinoma of the prostate are rare.

Sarcoma, lymphoma, small cell carcinoma, and transitional carcinoma of the prostate are rare.

Primary and secondary Gleason grades are determined by the histologic architecture of biopsy tissue. The primary grade denotes the dominant histologic pattern; the secondary grade represents the bulk of the nondominant pattern or a focal high-grade area. Primary and secondary grades range from 1 (well differentiated) to 5 (poorly differentiated). The combined grades comprise the GS (range 2 to 10). Gleason 6 or less are considered low risk, Gleason 7 is considered intermediate risk, and Gleason 8 to 10 is considered high risk.

Primary and secondary Gleason grades are determined by the histologic architecture of biopsy tissue. The primary grade denotes the dominant histologic pattern; the secondary grade represents the bulk of the nondominant pattern or a focal high-grade area. Primary and secondary grades range from 1 (well differentiated) to 5 (poorly differentiated). The combined grades comprise the GS (range 2 to 10). Gleason 6 or less are considered low risk, Gleason 7 is considered intermediate risk, and Gleason 8 to 10 is considered high risk.

A new grading system has been proposed and is being increasingly incorporated into pathologic review of prostate tumors. This system is designed to subdivide Gleason 7 based on morphology and dominant pathology and perhaps separate Gleason 8 from Gleason 9 and 10.

A new grading system has been proposed and is being increasingly incorporated into pathologic review of prostate tumors. This system is designed to subdivide Gleason 7 based on morphology and dominant pathology and perhaps separate Gleason 8 from Gleason 9 and 10.

There is no role in re-evaluating GS once treatment has begun.

There is no role in re-evaluating GS once treatment has begun.

At diagnosis, because of sampling bias, GS may change following radical prostatectomy (RP) (20% of scores are upgraded and up to 10% are downgraded).

At diagnosis, because of sampling bias, GS may change following radical prostatectomy (RP) (20% of scores are upgraded and up to 10% are downgraded).

Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), and perhaps proliferative inflammatory atrophy (PIA), are considered precursor lesions.

Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), and perhaps proliferative inflammatory atrophy (PIA), are considered precursor lesions.

Baseline Evaluation

In candidates for local treatment, a bone scan is indicated for patients with bone pain, T3 or T4, GS >7, or PSA >10 ng/mL. There is no clinical evidence that a baseline bone scan improves survival in populations with better prognostic factors.

In candidates for local treatment, a bone scan is indicated for patients with bone pain, T3 or T4, GS >7, or PSA >10 ng/mL. There is no clinical evidence that a baseline bone scan improves survival in populations with better prognostic factors.

In candidates for surgery, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis is obtained for T3 and T4 lesions, PSA >20 ng/mL, or GS >7 to detect enlarged lymph nodes. Endorectal MRI may help in determining the presence of extraprostatic extension. CT scans aid in treatment planning for radiation therapy (RT).

In candidates for surgery, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis is obtained for T3 and T4 lesions, PSA >20 ng/mL, or GS >7 to detect enlarged lymph nodes. Endorectal MRI may help in determining the presence of extraprostatic extension. CT scans aid in treatment planning for radiation therapy (RT).

Baseline laboratory tests include complete blood count, creatinine level, PSA (if not yet done), testosterone, and alkaline phosphatase level.

Baseline laboratory tests include complete blood count, creatinine level, PSA (if not yet done), testosterone, and alkaline phosphatase level.

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

Stage at diagnosis

Stage at diagnosis

Gleason Score

Gleason Score

PSA level

PSA level

Number of cores and percentage of each core involved

Number of cores and percentage of each core involved

Inherited genomic abnormalities

Inherited genomic abnormalities

TREATMENT OF LOCALIZED DISEASE

Active Surveillance

For men aged 60 to 75 years with a >10-year life expectancy or low-grade (GS ≤ 6), T1c-T2a tumors, active surveillance is a reasonable alternative to immediate local therapy. In addition, men aged 50 to 60 years with those same features and low-volume (<3 cores, <50% of any one core involved) tumor may also be candidates for active surveillance. For patients with a <10-year life expectancy, CaP-specific mortality is very low and local definitive therapy may not be appropriate.

Surgery

Approaches include retropubic (RRP), perineal (RPP), or laparoscopic, with the latter often done with robotic assistance (RALP). Typical hospital stays are 1 to 2 days, with 7 to 14 days of urethral catheterization. Surgeries are somewhat longer with RALP, but hospital stays are usually shorter.

Approaches include retropubic (RRP), perineal (RPP), or laparoscopic, with the latter often done with robotic assistance (RALP). Typical hospital stays are 1 to 2 days, with 7 to 14 days of urethral catheterization. Surgeries are somewhat longer with RALP, but hospital stays are usually shorter.

Pelvic lymph node dissection may be performed at the time of RP in patients at high risk of developing positive lymph nodes, but may not be necessary in patients with T1c disease, PSA <10 ng/mL, and GS <7.

Pelvic lymph node dissection may be performed at the time of RP in patients at high risk of developing positive lymph nodes, but may not be necessary in patients with T1c disease, PSA <10 ng/mL, and GS <7.

Nerve-sparing RP may conserve potency in men with disease not adjacent to the neurovascular bundles that travel posterior-lateral to the prostate. The bilateral nerve-sparing technique is associated with 60% to 90% of patients recovering spontaneous erections versus only 10% to 50% with the unilateral technique. Both groups, however, may respond to oral therapy for erectile dysfunction.

Nerve-sparing RP may conserve potency in men with disease not adjacent to the neurovascular bundles that travel posterior-lateral to the prostate. The bilateral nerve-sparing technique is associated with 60% to 90% of patients recovering spontaneous erections versus only 10% to 50% with the unilateral technique. Both groups, however, may respond to oral therapy for erectile dysfunction.

There is no role for neoadjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) prior to RP, although ongoing studies in high-risk patients are evaluating ADT with modern antiandrogens (enzalutamide and abiraterone) to determine the potential to decrease or eliminate tumor prior to RP.

There is no role for neoadjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) prior to RP, although ongoing studies in high-risk patients are evaluating ADT with modern antiandrogens (enzalutamide and abiraterone) to determine the potential to decrease or eliminate tumor prior to RP.

Patients with microscopic lymph node metastasis diagnosed following RP may have a longer overall survival (OS) if given ADT rather than at time of clinical recurrence/metastatic disease.

Patients with microscopic lymph node metastasis diagnosed following RP may have a longer overall survival (OS) if given ADT rather than at time of clinical recurrence/metastatic disease.

Salvage RP following RT may be done in select cases where local disease is organ confined. However, salvage RP is more technically demanding and is associated with higher morbidity.

Salvage RP following RT may be done in select cases where local disease is organ confined. However, salvage RP is more technically demanding and is associated with higher morbidity.

Immediate morbidity or mortality: less than 10%.

Immediate morbidity or mortality: less than 10%.

Impotence: 20% to 60%, varying with age and extent of disease.

Impotence: 20% to 60%, varying with age and extent of disease.

Urinary incontinence: improves with time, generally less than 10% to 15% 2 years after surgery.

Urinary incontinence: improves with time, generally less than 10% to 15% 2 years after surgery.

Urinary structure: approximately 10%, most can be managed with simple dilatation.

Urinary structure: approximately 10%, most can be managed with simple dilatation.

Inguinal Hernia: approximately 10%, but substantially less with minimally invasive surgery.

Inguinal Hernia: approximately 10%, but substantially less with minimally invasive surgery.

The Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study found statistically significant differences in outcomes following RP or RT. For patients with normal baseline function, RP was associated with inferior urinary function, better bowel function, and similar sexual dysfunction compared with RT.

The Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study found statistically significant differences in outcomes following RP or RT. For patients with normal baseline function, RP was associated with inferior urinary function, better bowel function, and similar sexual dysfunction compared with RT.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation Therapy as Definitive Therapy

External beam RT (EBRT) targets the whole prostate, frequently including a margin of extraprostatic tissue, seminal vesicles, and pelvic lymph nodes.

External beam RT (EBRT) targets the whole prostate, frequently including a margin of extraprostatic tissue, seminal vesicles, and pelvic lymph nodes.

Higher doses given over approximately 8 weeks are associated with higher PSA control rates, but shorter courses of therapy are also under investigation.

Higher doses given over approximately 8 weeks are associated with higher PSA control rates, but shorter courses of therapy are also under investigation.

Three-dimensional (3D) conformal RT allows for maximal doses conforming to the treatment field, while sparing normal tissue.

Three-dimensional (3D) conformal RT allows for maximal doses conforming to the treatment field, while sparing normal tissue.

Intensity-modulated RT is a type of 3D conformal RT that is designed to conform even more precisely to the target.

Intensity-modulated RT is a type of 3D conformal RT that is designed to conform even more precisely to the target.

Proton beam irradiation focuses virtually greater energy within a very small area, thus theoretically minimizing damage to normal tissue.

Proton beam irradiation focuses virtually greater energy within a very small area, thus theoretically minimizing damage to normal tissue.

Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) may allow for higher doses of radiation to be given in less fractions.

Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) may allow for higher doses of radiation to be given in less fractions.

There is incomplete data comparing EBRT, proton and SBRT at this time and so patients should have discussions about the relative benefits of these options with their radiation oncologists.

There is incomplete data comparing EBRT, proton and SBRT at this time and so patients should have discussions about the relative benefits of these options with their radiation oncologists.

At least three randomized controlled trials have shown that combining ADT with RT in patients at high risk for recurrent disease (Table 14.1) improves OS. ADT is usually given during RT and for 2 to 3 years thereafter. It may also be used for 2 months prior to RT to help decrease tumor size and thus the target volume of RT. For patients with intermediate risk disease, 6 months of ADT has demonstrated improved outcomes as well.

RT with Adjuvant ADT and Chemotherapy

A randomized phase III trial suggested that in high risk patients, six infusions of docetaxel 75 mg/m2 administered in 21-day cycles with prednisone starting 28 days after RT improved 4-year OS (93% vs. 86%; HR 0.49 using a one-sided 0.05 type I error and 90% power). One key limitation of this study was the use of a one-sided type I error, raising concerns about the robustness of the data. It remains unclear how widely adopted this approach is, but longer follow-up will certainly be of interest.

TABLE 14.1 Risk Categories for Post-therapy Prostate-Specific Antigen Failure

Lowa | Intermediateb | Highb | |

Stage | T1c, T2a | T2b | T2c |

PSA | <10 | 10–20 | >20 |

Gleason score | ≤6 | 7 | ≥8 |

a All parameters required.

b Only one parameter required.

Adapted from D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Optimizing patient selection for dose escalation techniques using the prostate-specific antigen level, biopsy Gleason score, and clinical T-stage. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45(5):1227–1233.

Interstitial brachytherapy with radioactive palladium or iodine seeds that delivers a much higher dose of radiation to the prostate is used in CaP patients with low-risk tumors and some intermediate-risk patients. Better definitions of tumor volume and radiation dosimetry have made this outpatient technique more accurate. CT and/or transrectal ultrasound are used to guide seed placement.

Combined EBRT and Brachytherapy

EBRT followed by brachytherapy boost is an increasingly used strategy. Preliminary clinical data support the safety and efficacy of this approach in a selected population of patients, but long-term follow-up and head to head comparisons is lacking. Nonetheless, many radiation oncologists are using this treatment combination in patients with high-risk disease.

General indications for the use of adjuvant RT after RP include positive surgical margins, seminal vesicle involvement, and evidence of extracapsular extension. Nonetheless, the potential for cure with adjuvant RT will vary significantly from patient to patient and thus the risks and benefits of adjuvant RT should be evaluated in each case individually. Some studies have indicated that lower PSA and Gleason score have been associated with better disease-free survival.

General indications for the use of adjuvant RT after RP include positive surgical margins, seminal vesicle involvement, and evidence of extracapsular extension. Nonetheless, the potential for cure with adjuvant RT will vary significantly from patient to patient and thus the risks and benefits of adjuvant RT should be evaluated in each case individually. Some studies have indicated that lower PSA and Gleason score have been associated with better disease-free survival.

For select patients with rising PSA after RP and a high likelihood of organ-confined local recurrence (e.g., PSA <1.0 and slowly rising), salvage RT may be considered. However, there are limited data on which to make recommendations.

Acute (Typically Resolve within 4 Weeks)

Cystitis

Cystitis

Proctitis/enteritis

Proctitis/enteritis

Fatigue

Fatigue

Impotence (30% to 45%)

Impotence (30% to 45%)

Incontinence (3%)

Incontinence (3%)

Frequent bowel movements (10% more than with RP)

Frequent bowel movements (10% more than with RP)

Urethral stricture (RT delayed 4 weeks after transurethral resection of the prostate).

Urethral stricture (RT delayed 4 weeks after transurethral resection of the prostate).

Focal Therapy for Disease Confined to a Region of the Prostate

Focal therapy for newly diagnosed CaP confined to a limited area of the prostate remains investigational. This strategy is different from other therapies for localized disease in that only a focal region of the prostate, as opposed to the entire glad, is targeted with hopes of limiting side effects. Cryosurgery destroys CaP cells through probes that subject prostate tissue to freezing followed by thawing. This procedure is associated with the high rates of erectile dysfunction due to freezing of the neurovascular bundle. Additional focal therapy strategies include thermal ablation via laser or high-intensity focused ultrasound among other techniques. There are limited data in highly selected populations on long-term outcomes for focal therapy. Thus, at most centers prostate focal therapies are largely reserved for consideration as salvage procedures.

COMPARISON OF PRIMARY TREATMENT MODALITIES

Comparing treatment modalities in terms of overall and disease-free survival is difficult because of the differences in study design, patient selection, and treatment techniques. Randomized trials are difficult to accrue to as patient choice for radiation or surgery can often not be overcome. Historical comparisons are flawed because patients with more comorbidities or advanced age often get radiation.

While there are no satisfactory randomized trials comparing RT with RP, these approaches appear to have similar PSA-free survival (also called biochemical relapse-free survival) in appropriately matched patients at 5 years, but differ in type and frequency of side effects.

While there are no satisfactory randomized trials comparing RT with RP, these approaches appear to have similar PSA-free survival (also called biochemical relapse-free survival) in appropriately matched patients at 5 years, but differ in type and frequency of side effects.

In recent years, high risk patients who previously were treated predominantly with radiation and adjuvant ADT are increasingly having surgery. To some degree this is related to the emergence of MRI imaging where discrete lesions and possible extracapsular extension is better defined. Longer follow-up is required to determine the impact of surgery in this population.

In recent years, high risk patients who previously were treated predominantly with radiation and adjuvant ADT are increasingly having surgery. To some degree this is related to the emergence of MRI imaging where discrete lesions and possible extracapsular extension is better defined. Longer follow-up is required to determine the impact of surgery in this population.

FOLLOW-UP AFTER DEFINITIVE TREATMENT

Patients treated with curative intent should have PSA levels checked at least every 6 months for 5 years, then annually. Annual DRE is appropriate for detecting recurrence.

Patients treated with curative intent should have PSA levels checked at least every 6 months for 5 years, then annually. Annual DRE is appropriate for detecting recurrence.

After RP, a detectable PSA suggests a relapse. PSA failure after RT is defined as 2 ng/mL over the nadir, whether or not the patient had ADT with RT.

After RP, a detectable PSA suggests a relapse. PSA failure after RT is defined as 2 ng/mL over the nadir, whether or not the patient had ADT with RT.

TREATMENT FOR MEN WITH RISING PSA AFTER LOCAL THERAPY

Treatment for patients who have rising PSA (biochemical failure) after local therapy has not been standardized and clinical trial data is incomplete (Fig. 14.1).

Treatment for patients who have rising PSA (biochemical failure) after local therapy has not been standardized and clinical trial data is incomplete (Fig. 14.1).

Salvage RT, salvage RP, or salvage focal therapy (as previously described) may be offered to select patients with local recurrence.

Salvage RT, salvage RP, or salvage focal therapy (as previously described) may be offered to select patients with local recurrence.

Men may live more than a decade after biochemical failure, thus a more conservative approach (e.g., surveillance, treating when symptomatic or based on PSA velocity) is a reasonable option for many men.

Men may live more than a decade after biochemical failure, thus a more conservative approach (e.g., surveillance, treating when symptomatic or based on PSA velocity) is a reasonable option for many men.

Using PSA doubling time (i.e., less than 3 to 6 months) as a trigger to initiate ADT is frequently done in clinical practice; however, no randomized trials have prospectively evaluated this approach. Retrospective data suggests that a PSA doubling time of less than 3 to 6 months may be associated with development of metastatic disease visible on conventional imaging.

Using PSA doubling time (i.e., less than 3 to 6 months) as a trigger to initiate ADT is frequently done in clinical practice; however, no randomized trials have prospectively evaluated this approach. Retrospective data suggests that a PSA doubling time of less than 3 to 6 months may be associated with development of metastatic disease visible on conventional imaging.

ADT effectively lowers PSA; however, there are no definitive data indicating better survival with ADT than with no ADT in biochemical recurrent prostate cancer.

ADT effectively lowers PSA; however, there are no definitive data indicating better survival with ADT than with no ADT in biochemical recurrent prostate cancer.

Randomized data from over 1,300 subjects demonstrated that ADT given intermittently (in 8-month cycles) was non-inferior to continuous ADT in terms of OS. Intermittent ADT was predictably associated with better quality of life outcomes.

Randomized data from over 1,300 subjects demonstrated that ADT given intermittently (in 8-month cycles) was non-inferior to continuous ADT in terms of OS. Intermittent ADT was predictably associated with better quality of life outcomes.

Emerging imaging platforms that are more sensitive at detecting (micro) metastatic disease may alter how this stage of disease is managed in the future.

Emerging imaging platforms that are more sensitive at detecting (micro) metastatic disease may alter how this stage of disease is managed in the future.

FIGURE 14.1Treatment options for biochemical recurrence/nonmetastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Continuous ADT employs repeated doses of GnRH agonists/antagonists to provide a constant testosterone suppression. Orchiectomy would also be an option. Intermittent ADT employs two or three-month doses of testosterone-lowering therapy, which are then discontinued if the PSA declines as expected. From there, PSA slowly recovers, lagging behind testosterone recovery. In selected patients, this approach can be used to alleviate some ADT toxicity. ADT is often reinstituted based on a PSA doubling time similar to the “surveillance of PSA” approach described in the figure.

TREATMENT OF SYSTEMIC DISEASE EVOLUTION OF RESPONSE CRITERIA IN METASTATIC DISEASE

The Prostate Cancer Working Group 3 and the Implications for Clinical Practice

As the understanding of CaP has evolved in the past decade, in the context of new available therapies and greater experience with older therapies, a consensus was generated by Prostate Cancer Working Group 3 (PSWG3) on determining response in clinical trials.

As the understanding of CaP has evolved in the past decade, in the context of new available therapies and greater experience with older therapies, a consensus was generated by Prostate Cancer Working Group 3 (PSWG3) on determining response in clinical trials.

Perhaps most importantly, PSA should not be used as the sole criteria to discontinue a therapy. Furthermore, the PSWG3 recommends that early changes in PSA and modest increases in pain, which could represent a tumor flare phenomenon, should not result in the discontinuation of therapy. This is especially important because PSA was not solely used to evaluate response of some of the latest therapies, thus discontinuing based on PSA alone could diminish the expected benefits of some therapies.

Perhaps most importantly, PSA should not be used as the sole criteria to discontinue a therapy. Furthermore, the PSWG3 recommends that early changes in PSA and modest increases in pain, which could represent a tumor flare phenomenon, should not result in the discontinuation of therapy. This is especially important because PSA was not solely used to evaluate response of some of the latest therapies, thus discontinuing based on PSA alone could diminish the expected benefits of some therapies.

For patients with metastatic CaP, objective changes on imaging studies (CT and bone scan) should be the primary criteria used to assess progression of disease in the absence of clear clinical progression of symptoms.

For patients with metastatic CaP, objective changes on imaging studies (CT and bone scan) should be the primary criteria used to assess progression of disease in the absence of clear clinical progression of symptoms.

To assess imaging, lymph nodes must be greater than 2 cm at baseline. In addition, physician discretion can be used for baseline lymph nodes less than 1.0 cm that grow to larger than 1.5 cm.

To assess imaging, lymph nodes must be greater than 2 cm at baseline. In addition, physician discretion can be used for baseline lymph nodes less than 1.0 cm that grow to larger than 1.5 cm.

Two new bone lesions on bone scan are required to document progressive disease, with one important exception. New lesions on the first bone scan should trigger another bone scan 6 or more weeks later, as these new lesions may have been present on the first scan, but missed on initial imaging or they may represent the “tumor flare phenomenon.” If the second (and subsequent) bone scans show less than two new lesions and the patient is otherwise clinically stable, he should be considered to have stable disease.

Two new bone lesions on bone scan are required to document progressive disease, with one important exception. New lesions on the first bone scan should trigger another bone scan 6 or more weeks later, as these new lesions may have been present on the first scan, but missed on initial imaging or they may represent the “tumor flare phenomenon.” If the second (and subsequent) bone scans show less than two new lesions and the patient is otherwise clinically stable, he should be considered to have stable disease.

For the treatment of patients outside of clinical trials the implications of the PCWG3 are as follows:

For the treatment of patients outside of clinical trials the implications of the PCWG3 are as follows:

•Radiographic response criteria should be used to determine disease progression in metastatic CaP as opposed to PSA alone.

•Initial changes on bone scan are not sufficient to remove patients from a treatment; patients could continue therapy if subsequent bone scans show less than two new lesions.

•Changes in lymph nodes less than 2 cm in diameter should be interpreted with caution.

•PSA should still be followed but interpreted with caution and not be used as a singular criteria to determine when to discontinue a therapy.

THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES FOR METASTATIC DISEASE ANDROGEN-DEPRIVATION THERAPY

ADT is the mainstay of treatment for metastatic CaP (Table 14.2), in addition to its potential role with localized disease and in neoadjuvant and adjuvant setting with RT.

ADT is the mainstay of treatment for metastatic CaP (Table 14.2), in addition to its potential role with localized disease and in neoadjuvant and adjuvant setting with RT.

Bilateral surgical castration and depot injections of GnRH agonists (e.g., leuprolide, goserelin, and buserelin) and a GnRH antagonist (degarelix) provide equally effective testosterone suppression. Combined androgen blockade can be achieved by adding an oral androgen receptor antagonist (ARA; e.g., nilutamide, flutamide, and bicalutamide). However, this is controversial and provides little if any definitive survival benefit.

Bilateral surgical castration and depot injections of GnRH agonists (e.g., leuprolide, goserelin, and buserelin) and a GnRH antagonist (degarelix) provide equally effective testosterone suppression. Combined androgen blockade can be achieved by adding an oral androgen receptor antagonist (ARA; e.g., nilutamide, flutamide, and bicalutamide). However, this is controversial and provides little if any definitive survival benefit.

GnRH agonists initially increase gonadotropin, causing a transient (~14 day) increase in testosterone that can lead to tumor flare. Tumor flare can be prevented by the use of an ARA, which binds to the androgen receptor (AR), effectively stopping the ability of the AR to activate cell growth. An ARA is often given for 1 to 2 weeks prior to GnRH agonist in patients at risk for complications (pain, obstruction, and cord compression) associated with tumor flare. For high-risk patients, bilateral orchiectomy can decrease testosterone more quickly.

GnRH agonists initially increase gonadotropin, causing a transient (~14 day) increase in testosterone that can lead to tumor flare. Tumor flare can be prevented by the use of an ARA, which binds to the androgen receptor (AR), effectively stopping the ability of the AR to activate cell growth. An ARA is often given for 1 to 2 weeks prior to GnRH agonist in patients at risk for complications (pain, obstruction, and cord compression) associated with tumor flare. For high-risk patients, bilateral orchiectomy can decrease testosterone more quickly.

The use of the GnRH antagonist (degarelix) obviates the concern for tumor flare as it leads to more rapid reduction in testosterone without an initial increase in serum testosterone levels. For this reason, it may be preferred in the setting of initial treatment for men diagnosed with symptomatic metastatic disease.

The use of the GnRH antagonist (degarelix) obviates the concern for tumor flare as it leads to more rapid reduction in testosterone without an initial increase in serum testosterone levels. For this reason, it may be preferred in the setting of initial treatment for men diagnosed with symptomatic metastatic disease.

•CaP cells generally respond to ADT, producing durable remissions and significant palliation. Duration of response ranges from 12 to 18 months, with a limited number of patients having a complete biochemical response for several years. Ultimately, for most patients CRPC cells emerge and lead to disease progression.

Continuing testosterone suppression after patients develop CRPC is also considered the standard of care for both nonmetastatic and metastatic disease. Androgens still play a very important role in driving the growth of CRPC, as evidenced by the benefits seen with new antiandrogen therapy (enzalutamide and abiraterone) in metastatic CRPC (mCRPC). Levels of AR and intracellular androgens within the tumor cells are significantly elevated in these patients and thus continuing ADT indefinitely in CRPC is recommended.

Continuing testosterone suppression after patients develop CRPC is also considered the standard of care for both nonmetastatic and metastatic disease. Androgens still play a very important role in driving the growth of CRPC, as evidenced by the benefits seen with new antiandrogen therapy (enzalutamide and abiraterone) in metastatic CRPC (mCRPC). Levels of AR and intracellular androgens within the tumor cells are significantly elevated in these patients and thus continuing ADT indefinitely in CRPC is recommended.

TABLE 14.2 Systemic Therapies for Prostate Cancer

Treatment | Dose | Most Common Side Effects |

Bilateral orchiectomy | N/a | Impotence, loss of libido, gynecomastia, hot flashes, and osteoporosis |

GnRH agonists (most common formulations) | ||

Goserelin acetate (Zoladex) | 3.6 mg SC every month or 10.8 mg SC every 3 mo | Potential for tumor flare due to transient initial increase in testosterone, loss of libido, gynecomastia, hot flashes, and osteoporosis |

Leuprolide acetate (Lupron) | 7.5 mg SC every month or 22.5 mg i.m. every 3 mo, or 30 mg SC every 4 mo | Potential for tumor flare due to transient initial increase in testosterone, loss of libido, gynecomastia, hot flashes, and osteoporosis |

GnRH agonist | ||

Degarelix (Firmagon) | 240 mg SC initial dose followed by 80 mg SC every 28 d | Hot flashes, weight gain, erectile dysfunction, loss of libido, hypertension, hepatotoxicity, gyecomastia, and osteoporosis |

Androgen receptor antagonists (ARAs) | ||

Bicalutamide (Casodex) | 50 mg PO daily | Nausea, breast tenderness, hepatotoxicity, hot flashes, loss of libido, and impotence |

Flutamide (Eulexin) | 250 mg PO three times per day | Diarrhea, nausea, breast tenderness, hepatotoxicity, loss of libido, and impotence |

Nilutamide (Nilandron) | 150 mg PO daily | Visual field changes (night blindness or abnormal adaptation to darkness), hepatotoxicity, impotence, loss of libido, hot flashes, nausea, disulfiram-like reaction, and pulmonary fibrosis (rare) |

Androgen biosynthesis inhibitors | ||

Ketoconazole (Nizoral) | 200 or 400 mg PO 3 times a day with hydrocortisone 20 mg PO in the morning and 10 mg in the evening. (Ketoconazole is absorbed at an acidic pH; therefore, the concomitant use of H2 blockers, antacids, or proton pump inhibitors should be avoided.) | Adrenal insufficiency is limited with physiologic dosing of hydrocortisone. Other side effects include impotence, pruritus, nail changes, adrenal insufficiency, nausea, emesis, and hepatotoxicity. (Ketoconazole is a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4, and thus multiple drug interactions are possible so review of medications is important.) |

Abiraterone (Zytiga) | 1,000 mg PO daily (on an empty stomach) Taken with prednisone 5 mg PO twice a day | Peripheral edema, hypertension, fatigue, hypokalemia, hypernatremia, increased triglycerides, hepatotoxicity, and hot flashes. (Abiraterone is a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4, and thus multiple drug interactions are possible, so review of medications is important.) |

Enzaluatmide | 160 mg PO once daily | Fatigue, hot flashes, diarrhea, peripheral edema, fatigue, arthralgia, and musculoskeletal pain. Limited risk of seizures (less than 1%) but care should be taken in patients with seizure history or those who are on medications that may lower the seizure threshold |

Immunotherapy | ||

Sipuleucel-T (Provenge) | Infusion of ≥50 million autologous CD54+ cells after ex vivo cellular processing given every 2 wk for three total doses | Fatigue, fever, chills, headache, nausea, emesis, myalgias, and infusion reaction symptoms |

Chemotherapy regimens | ||

Docetaxel (Taxotere) | 75 mg mg/m2 IV every 21 d with prednisone 5 mg PO twice daily | Granulocytopenia, infection, anemia, fatigue, anemia, neutropenia, fluid retention, sensory neuropathy, nausea, fatigue, myalgia, and alopecia |

Cabazitaxel (Jevtana) | 25 mg mg/m2 IV every 21 d with prednisone 5 mg PO twice daily | Myelosuppression, infection, fatigue/weakness, fever, diarrhea, nausea, emesis, peripheral neuropathy, arthralgias, peripheral edema, alopecia, and dyspepsia |

Mitoxantrone (Novantrone) | 12–14 mg mg/m2 IV every 21 d with prednisone 5 mg PO twice daily | Edema, myelosuppresion, cardiac toxicity, fever, fatigue, alopecia, nausea, diarrhea, infection, and hepatotoxicity |

Docetaxel (Taxotere) + carboplatin (Paraplatin) | Docetaxel at 60 mg/m2 with carboplatin AUC 4 every 21 d with daily prednisone 5 mg PO twice daily | Myelosuppression, infection, hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, pain, renal failure, and thrombosis. (These were seen in limited experience with 34 patients.) |

Radiopharmaceuticals | ||

Radium 223 | 6 monthly infusions at 55 kBq (1.49 microcurie) per kg IV | Myelosuppression, nausea, diarrhea, emesis, peripheral edema |

TREATMENT FOR METASTATIC CASTRATION-SENSITIVE PROSTATE CANCER

This population of patients develop metastatic disease with normal levels of testosterone (i.e., while not on therapy with ADT). This population includes men who have metastatic disease at their primary diagnosis or those who develop it while in the follow-up after definitive therapy but are not receiving ADT.

This population of patients develop metastatic disease with normal levels of testosterone (i.e., while not on therapy with ADT). This population includes men who have metastatic disease at their primary diagnosis or those who develop it while in the follow-up after definitive therapy but are not receiving ADT.

A randomized study (n = 790) established that six infusions of docetaxel (75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) substantially improved overall survival in this population 57.6 versus 44.0 months (HR 0.61). (Daily prednisone was not required.)

A randomized study (n = 790) established that six infusions of docetaxel (75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) substantially improved overall survival in this population 57.6 versus 44.0 months (HR 0.61). (Daily prednisone was not required.)

Docetaxel was required to be initiated within 120 days of starting ADT in this population.

Docetaxel was required to be initiated within 120 days of starting ADT in this population.

A subgroup analysis with longer follow-up has suggested that patients with low volume disease (less than four bone lesions, no visceral disease or no disease beyond the spine or pelvis) did not benefit from the addition of docetaxel to ADT, perhaps calling into question the benefits in the “low volume” population.

A subgroup analysis with longer follow-up has suggested that patients with low volume disease (less than four bone lesions, no visceral disease or no disease beyond the spine or pelvis) did not benefit from the addition of docetaxel to ADT, perhaps calling into question the benefits in the “low volume” population.

Emerging data from two additional studies in this population also indicates that abiraterone with ADT is superior to ADT alone. There is no clear evidence at this time as to which treatment, abiraterone or docetaxel is superior with ADT in this population.

Emerging data from two additional studies in this population also indicates that abiraterone with ADT is superior to ADT alone. There is no clear evidence at this time as to which treatment, abiraterone or docetaxel is superior with ADT in this population.

TREATMENT OF NONMETASTATIC CASTRATION-RESISTANT PROSTATE CANCER AND THE USE OF SECOND-LINE ARAS

Through the development of resistance mechanisms such as upregulation of the AR or intratumoral production of androgens, patients may develop progressive disease despite castration levels of testosterone (CRPC).

Through the development of resistance mechanisms such as upregulation of the AR or intratumoral production of androgens, patients may develop progressive disease despite castration levels of testosterone (CRPC).

For patients with a rising PSA but no evidence of metastatic disease ARAs can be added to ADT to provide a combined androgen blockade, which may delay disease progression or the development of metastasis.

For patients with a rising PSA but no evidence of metastatic disease ARAs can be added to ADT to provide a combined androgen blockade, which may delay disease progression or the development of metastasis.

Upon progression of disease with ARA and ADT, it is important to note that up to 20% of patients treated with combined androgen blockade have a PSA decline of ≥50% upon discontinuation of oral ARA (range, 15% to 33%), although these declines generally last only 3 to 5 months. This proportion may be lower with shorter-term use ARA use. This ARA withdrawal response occurs within 4 to 6 weeks, depending on the ARA’s half-life.

Upon progression of disease with ARA and ADT, it is important to note that up to 20% of patients treated with combined androgen blockade have a PSA decline of ≥50% upon discontinuation of oral ARA (range, 15% to 33%), although these declines generally last only 3 to 5 months. This proportion may be lower with shorter-term use ARA use. This ARA withdrawal response occurs within 4 to 6 weeks, depending on the ARA’s half-life.

Some patients with rising PSA (and still no evidence of metastasis) after ARA withdrawal may benefit from switching to other ARAs or initiating treatment with ketoconazole. A proportion of patients (35% to 50%) will have PSA declines with second-line and even third-line antiandrogen therapy.

Some patients with rising PSA (and still no evidence of metastasis) after ARA withdrawal may benefit from switching to other ARAs or initiating treatment with ketoconazole. A proportion of patients (35% to 50%) will have PSA declines with second-line and even third-line antiandrogen therapy.

Emerging data suggests enzalutamide induces superior progression-free survival relative to bicalutamude in nonmetastatic castration resistant prostate cancer.

Emerging data suggests enzalutamide induces superior progression-free survival relative to bicalutamude in nonmetastatic castration resistant prostate cancer.

TREATMENT FOR METASTATIC CASTRATION-RESISTANT PROSTATE CANCER

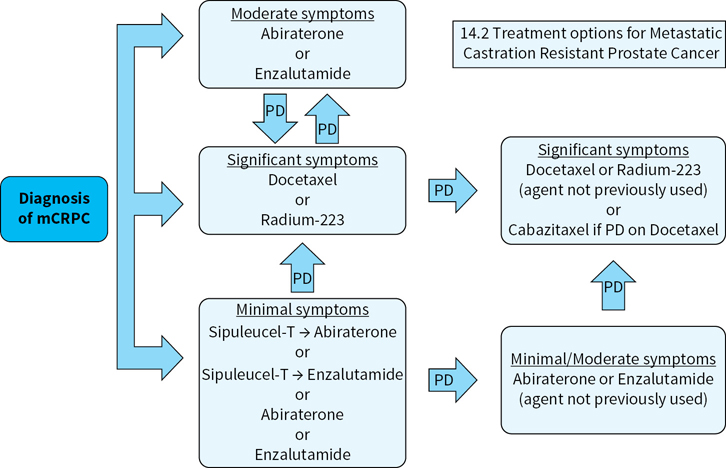

Multiple treatment options are now available for the treatment of mCRPC as opposed to prior to 2010 when only docetaxel had demonstrated the ability to extend survival in this population. Given multiple forms of therapy including immunotherapy, chemotherapy, radiopharmaceuticals, and modern antiandrogen therapy, symptoms and pace of disease will likely dictate which treatments are most appropriate for each individual patient. At this time no standard sequence of therapy has been demonstrated as most effective (Fig. 14.2).

FIGURE 14.2Suggested treatment approach for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. At this time there is no clear data on the optimal sequence in mCRPC. One strategy is to base treatment of mCRPC on presenting symptoms of the patient, selecting therapies that are less toxic for patients with minimal symptoms. Pace of disease should also be factored in, as rapidly progressing disease may require earlier chemotherapy, even before the onset of significant symptoms. Also, a brief previous response to ADT should temper the expectations for subsequent abiraterone or enzalutamide, as these particular disease manifestations may not be as dependent on the androgen receptor pathway for growth.

Immunotherapy

Sipuleucel-T (Provenge)—is an activated cellular therapy that is derived from a patient’s own immune cells, which are collected via leukapheresis. Once removed from circulation, the peripheral immune cells are sent to a central processing facility where they are exposed to a fusion peptide of PAP-GMCSF for 48 hours. The goal is to activate immune cells via ex vivo processing so that when they are reinfused into the patient, they generate an immune-mediated antitumor response.

Sipuleucel-T (Provenge)—is an activated cellular therapy that is derived from a patient’s own immune cells, which are collected via leukapheresis. Once removed from circulation, the peripheral immune cells are sent to a central processing facility where they are exposed to a fusion peptide of PAP-GMCSF for 48 hours. The goal is to activate immune cells via ex vivo processing so that when they are reinfused into the patient, they generate an immune-mediated antitumor response.

Although sipuleucel-T has been shown to improve survival versus placebo (25.8 vs. 21.7 months; HR 0.77; P = 0.02), it does not change short-term disease progression or cause decreases in PSA in most patients. For this reason, sipuleucel-T should ideally be followed by another therapy to provide short-term control and allow for the potential long-term effects, which can potentially improve survival. Patients whose disease on scans, PSA, and symptoms all remain stable after sipuleucel-T could be followed up closely until one of those parameters dictates the initiation of a subsequent therapy.

Although sipuleucel-T has been shown to improve survival versus placebo (25.8 vs. 21.7 months; HR 0.77; P = 0.02), it does not change short-term disease progression or cause decreases in PSA in most patients. For this reason, sipuleucel-T should ideally be followed by another therapy to provide short-term control and allow for the potential long-term effects, which can potentially improve survival. Patients whose disease on scans, PSA, and symptoms all remain stable after sipuleucel-T could be followed up closely until one of those parameters dictates the initiation of a subsequent therapy.

Sipuleucel-T is indicated in patients with minimal symptoms related to their CaP. Although sipuleucel-T can be given 3 months after chemotherapy, given its delayed effects, it would seem most appropriate to give this treatment prior to chemotherapy.

Sipuleucel-T is indicated in patients with minimal symptoms related to their CaP. Although sipuleucel-T can be given 3 months after chemotherapy, given its delayed effects, it would seem most appropriate to give this treatment prior to chemotherapy.

Androgen Biosynthesis Inhibitor

Abiraterone (Zytiga) is a selective and irreversible CYP17 inhibitor and significantly reduces secondary androgen production (including testosterone precursors dehydroepiandrosterone and androstenedione) from the adrenal glands and likely within CaP cells.

Abiraterone (Zytiga) is a selective and irreversible CYP17 inhibitor and significantly reduces secondary androgen production (including testosterone precursors dehydroepiandrosterone and androstenedione) from the adrenal glands and likely within CaP cells.

Abiraterone has demonstrated improved OS in mCRPC patients relative to placebo regardless of previous chemotherapy.

Abiraterone has demonstrated improved OS in mCRPC patients relative to placebo regardless of previous chemotherapy.

Abiraterone can be used in mCRPC patients who are chemotherapy-naïve and who have mild pain from their metastatic disease. It has been shown to delay the need for narcotics in this population.

Abiraterone can be used in mCRPC patients who are chemotherapy-naïve and who have mild pain from their metastatic disease. It has been shown to delay the need for narcotics in this population.

Abiraterone has also been shown to improve pain and quality of life in patients who have already received chemotherapy.

Abiraterone has also been shown to improve pain and quality of life in patients who have already received chemotherapy.

Abiraterone requires co-administration of prednisone (10 mg daily) to limit treatment-related toxicity.

Abiraterone requires co-administration of prednisone (10 mg daily) to limit treatment-related toxicity.

Androgen Receptor Inhibitor

Enzaluatmide (Xtandi) is a modern version of the ARAs previously discussed although this agent has broader anti-AR properties beyond binding to the AR with greater binding affinity. It also significantly reduces AR translocation to the nucleus and limits DNA binding, and inhibits coactivator recruitment and receptor-mediated DNA transcription. In addition, enzalutamide has not demonstrated any agonist properties unlike previous ARAs.

Enzaluatmide (Xtandi) is a modern version of the ARAs previously discussed although this agent has broader anti-AR properties beyond binding to the AR with greater binding affinity. It also significantly reduces AR translocation to the nucleus and limits DNA binding, and inhibits coactivator recruitment and receptor-mediated DNA transcription. In addition, enzalutamide has not demonstrated any agonist properties unlike previous ARAs.

Like abiraterone, enzalutamide has demonstrated efficacy compared to placebo in men with mCRPC regardless of previous chemotherapy and can improve moderate levels of pain.

Like abiraterone, enzalutamide has demonstrated efficacy compared to placebo in men with mCRPC regardless of previous chemotherapy and can improve moderate levels of pain.

Unlike abiraterone, enzalutamide does not require daily prednisone.

Unlike abiraterone, enzalutamide does not require daily prednisone.

Enzalutamide should not be used in patients with a seizure history or medications that may substantially lower the seizure threshold.

Enzalutamide should not be used in patients with a seizure history or medications that may substantially lower the seizure threshold.

CHEMOTHERAPY FOR mCRPC

In spite of the advent of new antiandrogen therapies for mCRPC, chemotherapy is still important in treating symptomatic disease.

Docetaxel (Taxotere)

Docetaxel (Taxotere)

•Improved median OS from 16.5 months (mitoxantrone/prednisone) to 18.9 months (P = 0.0005) and improved quality of life (functional assessment of cancer therapy-prostate, 22% vs. 13%; P = 0.009). Although the absolute magnitude of the difference between the two arms was less than 3 months, it is important to note that the study did employ a cross-over meaning that patients not randomized to docetaxel initially may have received docetaxel when they had progressive disease.

•Docetaxel is perhaps most appropriate for patients with mCRPC who have intermediate or significant levels of symptoms.

•Docetaxel would also be a reasonable option for patients with rapidly progressing disease as determined by objective changes on imaging.

Cabazitaxel (Jevtana)

Cabazitaxel (Jevtana)

•This treatment became the second chemotherapy approved for CaP. A phase III study trial compared this taxane with mitoxantrone in patients who already received docetaxel. (Prednisone 5 mg twice daily was also given in both groups.) Cabazitaxel improved time to progression 2.8 versus 1.4 months (P < 0.0001) but also met the primary endpoint of the trial by extending survival 15.1 versus 12.7 months (P < 0.0001).

•It is important to note that there was an 8% incidence of febrile neutropenia, and 2% of patients died from neutropenia-related infections. Thus serious consideration should be given for the use of growth factor support in appropriate patients.

•A study comparing docetaxel and cabazitaxel as frontline chemotherapy for mCRPC did not find that cabazitaxel was superior.

Mitoxantrone (Novantrone) + prednisone

Mitoxantrone (Novantrone) + prednisone

•Shown to improve quality of life, but not disease-free survival or OS, in two earlier randomized controlled trials versus steroids alone.

•Mitoxantrone is stopped at a cumulative dose of 140 mg/m2. Prochlorperazine is used as an antiemetic.

•Mitoxantrone may be appropriate for symptomatic patients who have either progressed on or who are not candidates for taxane-based chemotherapy regimens.

Docetaxel (Taxotere) + carboplatin

Docetaxel (Taxotere) + carboplatin

•A single-arm phase II trial of patients (n = 34) who progressed on docetaxel-based chemotherapy evaluated this combination and showed a partial response rate of 14% with a median progression-free survival of 3 months and an OS of 12.4 months.

•This combination may be most appropriate in patients who have a small cell variant of CaP (~2% of patients).

RADIOPHARMACEUTICALS FOR METASTATIC PROSTATE CANCER

The radioisotopes strontium-89 (Metastron) and Samarium-153 lexidronam (Quadramet) have previously demonstrated palliative benefits in mCRPC patients with bone disease, but were frequently associated with substantial myelosuppression.

The radioisotopes strontium-89 (Metastron) and Samarium-153 lexidronam (Quadramet) have previously demonstrated palliative benefits in mCRPC patients with bone disease, but were frequently associated with substantial myelosuppression.

The alpha-emitting radium-223 (Xofigo) has demonstrated the ability to have palliative benefits and, unlike its predecessors, the ability to extend OS in mCRPC. This benefit was seen in symptomatic patients regardless of previous chemotherapy.

The alpha-emitting radium-223 (Xofigo) has demonstrated the ability to have palliative benefits and, unlike its predecessors, the ability to extend OS in mCRPC. This benefit was seen in symptomatic patients regardless of previous chemotherapy.

Radium-223 has less impact on the bone marrow, because alpha particles have a limited destruction radius, but anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia can still be encountered.

Radium-223 has less impact on the bone marrow, because alpha particles have a limited destruction radius, but anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia can still be encountered.

Ultimately, radium-223 is commonly reserved for late stage, symptomatic patients because of the historic role of radioisotopes in mCRPC, but earlier use may be warranted. Safety data has suggested radium-223 can be safely given with abiraterone and enzalutamide, but it remains unclear if either combination is more beneficial than sequential use.

Ultimately, radium-223 is commonly reserved for late stage, symptomatic patients because of the historic role of radioisotopes in mCRPC, but earlier use may be warranted. Safety data has suggested radium-223 can be safely given with abiraterone and enzalutamide, but it remains unclear if either combination is more beneficial than sequential use.

Emerging Option: Poly (adenosine diphosphate [ADP]-ribose) polymerase (PARP)-Inhibitors

As described above, increasing data is suggesting that both germline defects and mutations in the DNA repair pathway are present in a subset of men with prostate cancer.

As described above, increasing data is suggesting that both germline defects and mutations in the DNA repair pathway are present in a subset of men with prostate cancer.

Early phase II data has suggested that prostate cancer patients with germline or somatic mutations overwhelming response rates to PARP-inhibitors.

Early phase II data has suggested that prostate cancer patients with germline or somatic mutations overwhelming response rates to PARP-inhibitors.

Larger studies are ongoing and the FDA has granted breakthrough therapy status to olaparib.

Larger studies are ongoing and the FDA has granted breakthrough therapy status to olaparib.

SUPPORTIVE MEASURES

Hot flashes from hormonal therapy are most commonly treated with low-dose venlafaxine or gabapentin with variable success. The potential side effects of these medicines also have to be taken into account when using them to treat hot flashes.

Hot flashes from hormonal therapy are most commonly treated with low-dose venlafaxine or gabapentin with variable success. The potential side effects of these medicines also have to be taken into account when using them to treat hot flashes.

Painful gynecomastia, often seen when ARAs are used alone, can be prevented with EBRT to the breasts (2 to 5 fractions) or may be treated with tamoxifen.

Painful gynecomastia, often seen when ARAs are used alone, can be prevented with EBRT to the breasts (2 to 5 fractions) or may be treated with tamoxifen.

Testosterone-lowering therapy causes a decrease in estradiol, needed to maintain bone density, which may lead to osteoporosis. Many specialists recommend that patients receiving ADT should be given daily vitamin D and calcium supplements unless contraindicated. Obtain baseline bone mineral density before starting long-term ADT. Treatment with bisphosphonates should be considered in patients with low bone mineral density.

Testosterone-lowering therapy causes a decrease in estradiol, needed to maintain bone density, which may lead to osteoporosis. Many specialists recommend that patients receiving ADT should be given daily vitamin D and calcium supplements unless contraindicated. Obtain baseline bone mineral density before starting long-term ADT. Treatment with bisphosphonates should be considered in patients with low bone mineral density.

MANAGEMENT OF BONE METASTASES

While narcotics can be used to alleviate bone pain, the anti-inflammatory effects of NSAIDs should not be overlooked in patients with bone metastasis as a first-line measure.

While narcotics can be used to alleviate bone pain, the anti-inflammatory effects of NSAIDs should not be overlooked in patients with bone metastasis as a first-line measure.

RT directed to painful spinal cord metastases provides palliation in approximately 80% of patients. Side effects generally are limited to fatigue and anemia that are usually reversible. Generally, the painful vertebral lesion and the two vertebrae superior to and inferior to the lesion are treated with 30 Gy. The spinal cord can tolerate radiation up to approximately 50 Gy, so retreatment of some lesions may be considered.

RT directed to painful spinal cord metastases provides palliation in approximately 80% of patients. Side effects generally are limited to fatigue and anemia that are usually reversible. Generally, the painful vertebral lesion and the two vertebrae superior to and inferior to the lesion are treated with 30 Gy. The spinal cord can tolerate radiation up to approximately 50 Gy, so retreatment of some lesions may be considered.

Bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclastic bone resorption and can decrease skeletal-related events in patients with advanced metastatic CRPC. Zoledronic acid 4 mg IV every 3 to 4 weeks has been approved for this indication. Side effects include infusion-related myalgias, renal dysfunction, and osteonecrosis of the jaw. Dose should be adjusted for renal insufficiency.

Bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclastic bone resorption and can decrease skeletal-related events in patients with advanced metastatic CRPC. Zoledronic acid 4 mg IV every 3 to 4 weeks has been approved for this indication. Side effects include infusion-related myalgias, renal dysfunction, and osteonecrosis of the jaw. Dose should be adjusted for renal insufficiency.

Denosumab (Xgeva) is a fully humanized antibody that binds to RANK-ligand that is crucial in the function of osteoclasts, which play a vital role in bone resorption. Even though it is mechanistically different from bisphosphonates, there is a similar incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Denosumab (Xgeva) is a fully humanized antibody that binds to RANK-ligand that is crucial in the function of osteoclasts, which play a vital role in bone resorption. Even though it is mechanistically different from bisphosphonates, there is a similar incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

In light of the potential toxicity and the benefits, treatment with bisphosphonates or RANK-ligand inhibitor could be considered for patients with disease in the spine and other weight-bearing bones of the pelvis and lower extremities.

In light of the potential toxicity and the benefits, treatment with bisphosphonates or RANK-ligand inhibitor could be considered for patients with disease in the spine and other weight-bearing bones of the pelvis and lower extremities.

SPINAL CORD COMPRESSION

Vertebral column metastases impinging on the spinal cord can cause spinal cord compression, an oncologic emergency common in patients with CaP who have widespread bone metastases.

Vertebral column metastases impinging on the spinal cord can cause spinal cord compression, an oncologic emergency common in patients with CaP who have widespread bone metastases.

Pain is an early sign of spinal cord compression in more than 90% of patients. Muscle weakness or neurologic abnormalities are other indicators of spinal cord compression, along with weakness and/or sensory loss corresponding to the level of spinal cord compression, which often indicate irreversible damage. Genitourinary, gastrointestinal, and autonomic dysfunction are late signs; spinal cord compression usually progresses rapidly at this point.

Pain is an early sign of spinal cord compression in more than 90% of patients. Muscle weakness or neurologic abnormalities are other indicators of spinal cord compression, along with weakness and/or sensory loss corresponding to the level of spinal cord compression, which often indicate irreversible damage. Genitourinary, gastrointestinal, and autonomic dysfunction are late signs; spinal cord compression usually progresses rapidly at this point.

Diagnosis requires a thorough history and physical, with special attention to musculoskeletal and neurologic examinations. The standard for diagnosing and localizing spinal cord compression is MRI, usually with gadolinium. A myelogram may be used in patients with contraindications to MRI such as a pacemaker.

Diagnosis requires a thorough history and physical, with special attention to musculoskeletal and neurologic examinations. The standard for diagnosing and localizing spinal cord compression is MRI, usually with gadolinium. A myelogram may be used in patients with contraindications to MRI such as a pacemaker.

High-dose steroids should be started (e.g., dexamethasone ≥24 mg IV followed by 4 mg IV or PO every 6 hours) as soon as history or neurologic examination suggests spinal cord compression.

High-dose steroids should be started (e.g., dexamethasone ≥24 mg IV followed by 4 mg IV or PO every 6 hours) as soon as history or neurologic examination suggests spinal cord compression.

Neurologic/orthopedic surgeons and/or radiation oncologists should be consulted soon after diagnosis.

Neurologic/orthopedic surgeons and/or radiation oncologists should be consulted soon after diagnosis.

Suggested Readings

1.Antonarakis ES, Feng Z, Trock BJ, et al. The natural history of metastatic progression in men with prostate-specific antigen recurrence after radical prostatectomy: long-term follow-up. BJU Int. 2012;109(1):32–39.

2.Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Wang H, et al. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):1028–1038.

3.Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(5):424–433.

4.Bolla M, Collette L, Blank L, et al. Long-term results with immediate androgen suppression and external irradiation in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer (an EORTC study): a phase III randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9327):103–106.

5.Bolla M, Gonzalez D, Warde P, et al. Improved survival in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy and goserelin. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(5):295–300.

6.Bolla M, van Poppel H, Tombal B, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy for high-risk prostate cancer: long-term results of a randomised controlled trial (EORTC trial 22911). Lancet. 2012;380(9858):2018–2027.

7.Crawford ED, Eisenberger MA, McLeod DG, et al. A controlled trial of leuprolide with and without flutamide in prostatic carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(7):419–424.

8.de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):1995–2005.

9.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1147–1154.

10.Eisenberger MA, Blumenstein BA, Crawford ED, et al. Bilateral orchiectomy with or without flutamide for metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(15):1036–1042.

11.Epstein JI, Zelefsky MJ, Sjoberg DD, et al. A contemporary prostate cancer grading system: A validated alternative to the Gleason score. Eur Urol. 2016 Mar;69(3):428–435.

12.Gleave M, Goldenberg L, Chin JL, et al. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy: update. J Urol. 2003;169(4):A690.

13.Granfors T, Modig H, Damber JE, Tomic R. Combined orchiectomy and external radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for nonmetastatic prostate cancer with or without pelvic lymph node involvement: a prospective randomized study. J Urol. 1998;159(6):2030–2034.

14.Hanks GE, Pajak TF, Porter A, et al. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Phase III trial of long-term adjuvant androgen deprivation after neoadjuvant hormonal cytoreduction and radiotherapy in locally advanced carcinoma of the prostate: the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Protocol 92-02. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(21):3972–3978.

15.Hoskin PJ, Motohashi K, Bownes P, et al. High dose rate brachytherapy in combination with external beam radiotherapy in the radical treatment of prostate cancer: initial results of a randomized phase three trial. Radiother Oncol. 2007;84(2):114–120.