Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation 30

Abraham S. Kanate, Michael Craig, and Mehdi Hamadani

INTRODUCTION

The effective therapeutic implementation of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) took the concerted efforts of several prominent investigators spanning the 20th century. Seminal work done predominantly on murine models identified the cellular basis of hematopoiesis and raised the possibility of HCT in humans in the first half of the 20th century. The latter half witnessed the successful (albeit with early setbacks) therapeutic application of human HCT. For his pioneering efforts in the field, Dr. E. Donnall Thomas received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1990. Currently, it is estimated that over 50,000 patients undergo HCT annually worldwide that includes both autologous (auto-HCT) and allogeneic (allo-HCT) transplantation.

Hematopoietic transplantation is an effective therapeutic option for patients with a wide range of malignant and benign conditions. While high dose therapy and auto-HCT, where the patient serves as the donor, are implemented chiefly in the management of multiple myeloma (MM) and lymphoma, allo-HCT is primarily used in the treatment of leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and bone marrow failures states and involves the transfer of hematopoietic cells from a donor to the patient. Apart from matched related donor (MRD) allo-HCT, patients may be offered allografts from matched unrelated donors (MUD), mismatched unrelated donors (MMUD), haploidentical related donors or umbilical cord blood (UCB). In recent years the application of HCT has broadened to include older and frail patients with the advent of reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens. Advances in supportive care, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing, prevention and treatment of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and better management of complications have led to improved survival and outcomes. A brief overview of autologous and allogeneic HCT is provided in this chapter, along with a discussion of the complications and their management.

HEMATOPOIETIC STEM CELLS

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) reside within the bone marrow space in close association with stromal cells and extracellular matrix proteins and are capable of producing progenitor cells that can reconstitute the hematopoietic system including lymphoid and myeloid cell lines. True HSC are characterized by their unlimited self-renewal capacity, pluripotency (ability to differentiate), quiescence and extensive proliferative capacity. While committed progenitor cells may retain some of the HSC properties and may repopulate the hematopoietic system, they lack self-renewal capacity. In humans, the HSC immunophenotype is characterized as CD34+, CD38 –, Thy-1low and lacking lineage-specific markers, although a population of CD34– stem cells has also been described. Considering the abundance of hematopoietic cells, true HSCs are relatively rare and constitute only 1 in 10,000 bone marrow cells. The HSC when infused to a recipient retains the ability to migrate and occupy bone marrow niches by virtue of surface adhesion molecules, chemokines and their receptors. The number of CD34+ cells in the infused graft product has important ramifications on post-HCT outcomes as lower CD34+ cell dose may be associated with a higher risk of graft failure, delayed engraftment and hematopoietic recovery resulting in higher non-relapse mortality (NRM).

STEM CELL SOURCES

Bone Marrow

Originally bone marrow was considered the sole source of acquiring HSCs for both autologous and allogeneic transplantation and is obtained via repeated aspiration of the marrow from the posterior iliac crest usually under general anesthesia. The goal is to obtain >2 x 108/kg recipient body weight of total nucleated/mononuclear cells (TNC) to allow safe engraftment. The maximum volume of marrow that may safely be removed at a given time is 20 mL/kg donor weight. The harvesting procedure is very well tolerated with no long-term adverse effects. Common side effects include pain at the procedure site, neuropathy, infection, and rarely anemia. Transfusion of autologous red cells obtained from the harvested product is considered in many centers. Transplantation with peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPC) has largely replaced marrow-derived HSCs as the choice of cells for almost all auto-HCT and majority of the allo-HCT in adult patients. However, marrow remains the chief source of HSCs in pediatric patients and in some adults with non-malignant hematological disorders such as aplastic anemia. Recent data have also led to resurgent use of marrow-derived products in unrelated and haploidentical-related donor HCT.

Peripheral Blood

Growth factors such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) are used to “mobilize” or increase the number of HSCs and progenitor cells in the peripheral blood, which are collected by apheresis. The minimum goal of PBPC collection is 2 x 106/kg recipient body weight of CD34+ cells. The PBPC collection is very safe with no long-term adverse effects to the donor. The administration of growth factors to healthy donors may produce minor bone pain, with splenic rupture and myocardial infraction being extremely rare but significant complications. Plerixafor is a chemokine receptor antagonist against CXCR4, which mobilizes HSC and is currently approved in combination with G-CSF prior to auto-HCT in lymphoma and myeloma patients. In the setting of auto-HCT, cytotoxic agents are sometimes used prior to G-CSF mobilization. The post-chemotherapy recovery phase improves the PBPC yield and may also in addition provide antineoplastic effects. PBPC grafts generally result in more rapid engraftment and hematopoietic recovery. Based on existing evidence, PBPC is preferred over marrow grafts in auto-HCT. It is more controversial in the setting of allo-HCT. Due to the 10 to 20 fold higher T-lymphocytes present in the PB product, there is concern for increased GVHD. Results of early comparative studies in MRD allo-HCT demonstrated earlier engraftment, similar acute GVHD and relapse rates, but increased chronic GVHD with the use of PBPC in some but not all studies. A randomized trial evaluating peripheral blood vs. bone marrow allo-HCT in the MUD setting showed increased chronic GVHD with the peripheral blood product, which was offset by delayed engraftment with marrow graft. Although graft source did not impact relapse rate or survival, long-term follow up suggest improved quality of life parameters with the use bone marrow allografts. Registry studies have shown increased chronic GVHD and poorer survival in patients receiving PBPC allo-HCT in severe aplastic anemia compared to those receiving bone marrow product, thus making it the graft source of choice in aplastic anemia. A risk-adapted approach, taking into account diagnosis, disease status, and donor type, is warranted in choosing the ideal graft source.

Umbilical Cord Blood

Umbilical cord blood (UCB) obtained from the umbilical cord and placenta after delivery of the baby is another source for HSC, which can be cryopreserved for later use. This represents an enriched source of HSC in a relative small volume of blood in comparison to bone marrow or PBPC and is readily available upon request but is expensive.

INDICATIONS FOR TRANSPLANTATION

Hematopoietic cell transplantation is considered a therapeutic option in the management of several disease entities. The National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) website, http://www.bethematch.org, provides a more complete list. See table 30.1 for common indications in adults. Some of the salient features are as follows:

In pediatric population (<20 years), chief indications for auto-HCT are non-hematological malignancies and for allo-HCT they are benign hematological and immune system disorders (erythrocyte disorders, inherited immune system defects, congenital metabolic diseases).

In pediatric population (<20 years), chief indications for auto-HCT are non-hematological malignancies and for allo-HCT they are benign hematological and immune system disorders (erythrocyte disorders, inherited immune system defects, congenital metabolic diseases).

In the adult population, myeloma and lymphoma are common indications for auto-HCT, while acute and chronic leukemias, myeloid neoplasms, lymphomas, myelodysplastic syndrome, and aplastic anemia are common indications for allo-HCT.

In the adult population, myeloma and lymphoma are common indications for auto-HCT, while acute and chronic leukemias, myeloid neoplasms, lymphomas, myelodysplastic syndrome, and aplastic anemia are common indications for allo-HCT.

Trends in HCT have changed over time with therapeutic advances. An important example is allo-HCT used to be standard of care for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) but not so in the era of bcr-abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Trends in HCT have changed over time with therapeutic advances. An important example is allo-HCT used to be standard of care for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) but not so in the era of bcr-abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

PRETRANSPLANT EVALUATION

Prior to treatment, a thorough discussion highlighting the transplantation procedure as well as risks and benefits associated with the procedure should take place between the physician and the patient.

1.HLA typing of the patient and a search for an HLA-matched donor is required if an allogeneic transplant is being considered. Donor search is initiated with matched siblings as first choice, followed by matched unrelated donors and alternative donors (haploidentical, UCB, and MMUD).

2.Medical history and evaluation.

•Age—remains an important predictor of treatment-related morbidity and mortality. However, with improving supportive care, HLA typing, and use of RIC regimens, physiologic age is considered more important than chronological age.

•Review of original diagnosis and previous treatments, including radiation.

•Concomitant medical problems.

•Current medications, important past medications, and allergies.

•Determination of current disease remission status and restaging (by imaging studies, bone marrow biopsy, flow cytometry on blood or bone marrow, lumbar puncture, tissue biopsy as warranted).

•Transfusion history and complications, as well as ABO typing and HLA antibody screening.

•Psychosocial evaluation and delineation of a caregiver.

3.Physical examination.

•Thorough physical examination including evaluation of oral cavity and dentition

•Neurologic evaluation to rule out central nervous system involvement, if indicated

•Performance status evaluation

4.Organ function analysis.

•Complete blood count.

•Renal function: Preferably a creatinine clearance >60 mL per minute, except in myeloma.

•Hepatic function: Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) less than twice the upper level of normal and bilirubin <2.00 μg/dL.

•Cardiac evaluation: Electrocardiogram and echocardiography or multiple-gated acquisition imaging with ejection fraction.

•Chest x-ray and pulmonary function testing, including diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide and forced vital capacity.

•The use of scoring schemes such as the hematopoietic cell transplantation specific-comorbidity index (HCT-CI) can predict NRM based on patient factors may be used to risk stratify patients.

5.Infectious disease evaluation.

•Cytomegalovirus (CMV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), toxoplasmosis, and hepatitis serology

•Serology for herpes simplex virus (HSV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and varicella zoster virus (VZV)

•Assess for prior history of invasive fungal (aspergillus) infection

6.Pregnancy testing for all women of child-bearing age and consideration of referral to reproductive center for sperm banking or in vitro fertilization.

AUTOLOGOUS HEMATOPOIETIC CELL TRANSPLANTATION

The principle behind high dose therapy (HDT) is the administration of maximal tolerated doses of cytotoxic agents and/or radiation to maximize tumor kill and overcome relative tumor resistance, which causes prolonged and lethal cytopenias from which the patient may be rescued with the infusion of autologous progenitor cells to reconstitute the hematopoietic system. HDT regimens typically use combinations of cytotoxic agents with non-overlapping organ toxicities. Commonly used regimens include (a) BEAM – carmustine + etoposide + cytarabine + melphalan (lymphoma), (b) CBV – cyclophosphamide + carmustine + etoposide (lymphoma), and (c) single agent melphalan 200 mg/m2 (myeloma). HDT is considered in chemotherapy sensitive tumors or as consolidation therapy for patients in remission (Table 30.1). Overall it is well tolerated with a NRM of < 5%. Typically, the auto-HCT product is mobilized with G-CSF alone or in combination with either chemotherapy or the chemokine antagonist plerixafor. The mobilized PBPC is collected by apheresis and is cryopreserved viably in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and thawed just prior to infusion. Complications related to HDT and auto-HCT include:

Rare infusion reactions may include bronchospasm, flushing, hypertension, or hypotension secondary to DMSO.

Rare infusion reactions may include bronchospasm, flushing, hypertension, or hypotension secondary to DMSO.

Pancytopenia is universal, packed red cell (PRBC) and platelet transfusions maybe required. Neutrophil recovery takes 10-14 days with GCSF support.

Pancytopenia is universal, packed red cell (PRBC) and platelet transfusions maybe required. Neutrophil recovery takes 10-14 days with GCSF support.

Infectious complications – bacterial, viral and fungal infections may manifest during the cytopenic phase but can be effectively prevented with antimicrobial prophylaxis. Late infections include Pneumocystis jiroveci and varicella reactivation require continued prophylaxis beyond engraftment.

Infectious complications – bacterial, viral and fungal infections may manifest during the cytopenic phase but can be effectively prevented with antimicrobial prophylaxis. Late infections include Pneumocystis jiroveci and varicella reactivation require continued prophylaxis beyond engraftment.

Regimen related toxicities may be (a) acute – infusion reaction (carmustine), hemorrhagic cystitis (cyclophosphamide), hypotension (etoposide) or (b) delayed – pulmonary toxicity (carmustine, total body irradiation (TBI)), sinusoidal obstruction syndrome or SOS (TBI or alkylating agents) and myelodysplasia (TBI, alkylating agents, etoposide).

Regimen related toxicities may be (a) acute – infusion reaction (carmustine), hemorrhagic cystitis (cyclophosphamide), hypotension (etoposide) or (b) delayed – pulmonary toxicity (carmustine, total body irradiation (TBI)), sinusoidal obstruction syndrome or SOS (TBI or alkylating agents) and myelodysplasia (TBI, alkylating agents, etoposide).

Relapse of the primary malignancy remains a major barrier to long-term survival.

Relapse of the primary malignancy remains a major barrier to long-term survival.

ALLOGENEIC HEMATOPOIETIC CELL TRANSPLANTATION

Allo-HCT has progressed from an experimental treatment of last resort to standard of care therapy for several disease conditions (Table 30.1). Extensive planning and co-ordination of care is required for all transplant candidates, usually involving a network of physicians and support staff. For patients without a MRD, the NMDP is an invaluable resource for the purpose of MUD allo-HCT. All physicians may perform a free initial search for an HLA-matched unrelated donor in the NMDP, which maintains a registry of about 13.5 million potential donors and 225,000 UCB units. As of 2016, the NMDP can search over 27 million MUD and 680,000 UCB units as potential donors through its international networks.

Graft-versus-Tumor Effect

In the context of malignancies, the major therapeutic benefit of allo-HCT is the potential for the donor immune system to recognize and eradicate the malignant stem cell clone, the so called graft-versus-tumor (GVT) effect. This immune effect is largely mediated by transplanted donor lymphocytes and is evidenced by the lower relapse rate of hematological malignancies in patients who undergo allo-HCT than in those who undergo auto-HCT, as well as by an increased risk of relapse in syngeneic (identical twin) donor or T-cell depleted allo-HCT. Arguably the most important and direct evidence for GVT effect comes from the ability of therapeutic donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) to induce remission in those that relapse after allo-HCT. CML, low-grade lymphomas, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are most susceptible to the GVT effects, whereas acute lymphoblastic leukemia and high-grade lymphomas are relatively resistant. Donor-derived T-lymphocytes predominantly mediate GVT reactions, although new evidence supports potential contribution from nonspecific cytokines (host and/or donor derived) and alloreactive natural killer (NK) cells (haploidentical allo-HCT).

Human Leukocyte Antigen Typing

The HLA system consists of a series of cell surface proteins and antigen-presenting cells encoded by the major histocompatibility complex located on chromosome 6 and play a vital role in immune recognition and function. A striking feature of the HLA system is its enormous diversity. HLA class-I molecules include HLA -A, -B, and -C antigens and class-II molecules are made up of more than 15 antigens (HLA -DP, -DQ, and -DR). The complexity of the HLA system was revealed with the advent of molecular-based HLA typing, which showed that matched HLA phenotypes by serologic testing (antigen level) were actually diverse when classified by DNA analysis (allele level). The importance of careful HLA matching prior to the selection of a donor cannot be over-emphasized and independently impacts graft failure, GVHD and overall survival (OS). High resolution HLA typing at the allele level is recommended for all recipients at HLA -A, -B, -C, and -DRB1 at the earliest as it avoids unnecessary delays in identifying a donor. The NMDP recommends rigorous matching at the allele level for HLA -A, -B, -C, and -DRB1 (8/8 match) for adult patients and donors and a less stringent match at HLA -A, -B (antigen level) and HLA -DRB1 (allele level) for UCB units.

Donor Types for Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation

1.Matched Related Donor (MRD)

In the United States, approximately 30% of patients will have an HLA-matched sibling and is the preferred donor source. The probability that a sibling pair is HLA matched is about 25%. The risk of GVHD is higher with increasing HLA disparity and therefore, most transplant centers prefer at least 6/6 HLA match (HLA -A, -B, -DRB1).

2.Syngeneic Donor

Rarely, an identical twin may serve as the donor. As the donor and recipient are genetically identical, GVHD does not typically occur (rarely noted, when a parous female serves as the donor) and post-HCT immunosuppression is not required. By the same principle, such HCT lack GVT effects and malignancy relapse risk tend to be higher.

3.Matched Unrelated Donor (MUD)

As discussed above the search for an appropriate MUD is performed through the NMDP. It typically takes 3 to 6 months from the time a suitable donor is located to obtaining the allograft, although this period may be shortened when expedited searches are requested. Seventy percent of Caucasians will have a suitable MUD, while it is more difficult for ethnic minorities owing to disparities in registered volunteers in the NMDP registry. High resolution (allele level) matching at HLA -A, B, C, and -DRB1 (8/8) is considered for MUD when possible additional matching at -DQ (10/10 match) and -DP (12/12 match) are considered. Recent data suggest high-resolution MUD allo-HCT have similar outcomes to MRD allo-HCT.

4.Alternative Donors

In the absence of an HLA-matched sibling donor, a MUD is traditionally considered. When a MUD is not available alternative donors may be used.

(i)Mismatched unrelated donors (MMUD)—MMUD are potential alternative donors. Studies have established that donor-recipient HLA mismatches decrease OS and increase the risk of GVHD and graft failure. Most centers consider a 7/8 match in this setting (at -A, -B, -C, and -DRB1) and the NMDP requires a minimum 6/8 match prior to approving a match. In MMUD it is important to look for (i) presence of recipient HLA antibodies against the donor HLA called donor-specific HLA antibodies (DSA) and (ii) matching at secondary HLA loci such as -DQB1, -DRB3/4/5, and -DP.

(ii)Haploidentical Donor—Ready availability of an unrelated donor remains a major concern for patients who are not Caucasians. Haploidentical-related donors (defined as >2 antigen level mismatches) are a less expensive and readily available source for most patients across ethnic and racial barriers. Early reports utilizing haploidentical donors were associated with prohibitive GVHD in T-cell replete grafts. Extensive in vivo or ex vivo T-cell depletion used to mitigate this risk led to a higher risk disease relapse, delayed immune reconstitution, infectious complications resulting in a higher NRM. A relatively newer strategy using marrow derived T-cell replete haploidentical allografts with post-transplant administration of high dose cyclophosphamide selectively targets alloreactive T-cells (effector cells implicated in acute GVHD) rapidly proliferating early after an HLA-mismatched transplant, but relatively sparing regulatory T-cells and nondividing hematopoietic cells, has shown encouraging results with prompt engraftment, low GVHD, and favorable NRM. Although lacking prospective data, large observational studies have demonstrated comparable post-transplant outcomes with haploidentical transplantation compared to more traditional MUD and MRD allo-HCT in leukemia and lymphoma. Haploidentical donor HCT is potentially an attractive choice for ethnic minorities and resource restricted regions.

(iii)Umbilical cord blood—Obtained and cryopreserved from a newborn’s cord, the presence of immunologically naïve immune cells allows for HLA mismatches without increasing the risk of GVHD. Graft rejection and delayed engraftment occur more frequently owing to lower number of nucleated cells. However, the simultaneous use of two UCB (double UCB) units from different donors has shown to improve engraftment. Higher total nucleated cell doses and better degrees of HLA match are associated with improved transplant outcomes. Current goal is to maximize matching at the antigen level for HLA-A and -B, and at the allele-level for and the NMDP recommends at least ≥4/6 HLA-matched cord blood unit with adequate cell dose and also to consider evaluating for HLA antibodies, HLA-C matching and screening for non-inherited maternal antigens (NIMA). The ideal alternative donor source is unknown and mostly dependent of the specific center’s expertise. An ongoing randomized trial (BMT CTN 1101) compares allo-HCT outcomes with double UCB versus haploidentical donors.

Donor Evaluation

Careful donor selection and evaluation is an integral part of the pretransplantation workup. The donor must be healthy and able to withstand the apheresis procedure or a bone marrow harvest.

1.HLA typing

2.ABO typing

3.History-relevant information of the donor:

Any previous malignancy within 5 years, except non-melanoma skin cancer, is considered and absolute exclusion criteria. Age, sex, and parity of the donor impacts HCT outcomes and though are not exclusion criteria; younger men and nonparous women are preferred when available. Comorbidities like cardiac or coronary artery disease, lung diseases, back or spine disorders, medications, and complications to general anesthesia to be considered.

4.Infection exposure

HIV, human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV), hepatitis, CMV, HSV, and EBV serology

5.Pregnancy testing for women

PHASES OF ALLOGENEIC TRANSPLANT

Pre-transplant Phase—Conditioning (“The Preparative Regimen”)

This phase of HCT precedes the graft infusion and is characterized by the administration of chemotherapeutic agents +/– radiation. In the conventional sense, the goals of the conditioning regimen include immunosuppression of the recipient to prevent graft rejection and to eradicate residual disease. Newer conditioning strategies such as RIC/NMA regimens preserve immunosuppressive effects to aid donor engraftment with minimal or no myelosuppression.

1.Myeloablative conditioning

The most commonly used myeloablative conditioning regimens incorporate high-dose cyclophosphamide (120 mg/Kg) in combination with TBI (usually 12 Gy) or busulfan. The choice of regimen is guided by factors such as the sensitivity of the malignancy to drugs in the regimen, the toxicities inherent to individual conditioning agents, prior therapies, and age and performance status of the patient. Early regimen-related toxicity include mucositis, nausea, diarrhea, alopecia, pancytopenia, seizures, and SOS. Late effects include pulmonary toxicity, hypothyroidism, growth retardation, infertility, an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and second malignancies (mostly related to TBI).

2.Nonmyeloablative (NMA)/Reduced intensity conditioning (RIC)

RIC or NMA conditioning provides immunosuppression to aid donor engraftment and relies principally on the GVT reactions to eliminate residual malignancy. Cytopenias are limited requiring no or minimal transfusion support. Commonly used truly NMA regimens incorporate fludarabine combined with low-dose TBI (<2 Gy) or alkylating agent such as cyclophosphamide, busulfan, or melphalan. While the division is somewhat arbitrary, RIC is intermediate between myeloablative and NMA regimens and is usually associated with cytopenias needing transfusion support. The advent of RIC/NMA regimens has broadened the applicability of allo-HCT to include older patients (>60), and those with poor performance status and co-morbidities. Regimen-related toxicity and NRM tend to be less. Unique to RIC/NMA is the presence of assortment of donor and recipient hematopoietic cells in the initial months post-HCT (called mixed chimerism). Several reports indicate that persistent mixed chimerism may lead to higher relapse rates. Immunosuppression withdrawal and less commonly DLI are implemented to convert mixed chimerism by the gradual donor-immune mediated eradication of recipient hematopoietic cells. GVT effects have been observed in several hematologic malignancies, as well as in select metastatic solid tumors such as renal cell carcinoma and neuroblastoma.

Transplant Phase

The transplantation phase is characterized by the intravenous infusion of the graft and usually starts 24 to 48 hours after completing the preparative regimen. Infusion is usually well tolerated by the recipient. The day of transplantation is traditionally referred to as “day 0.”

Post-transplant (pre-engraftment) Phase

Early post-transplant phase is characterized by marrow aplasia and pancytopenia. Regimen-related toxicity and infectious complications are common during this phase and usually require intensive support with aggressive hydration, antimicrobial prophylaxis and treatment, GVHD prophylaxis and transfusion support. All transfused products should be irradiated (to avoid transfusion associated GVHD) and leukoreduced (CMV safe). Engraftment is the term used to define hematopoietic recovery after HCT. Earliest to occur and sometimes used synonymously with the term engraftment is myeloid engraftment defined as sustained recovery of neutrophil count of >0.5x109/L. Platelet engraftment usually lags behind granulocyte recovery and is usually defined platelet counts of at least >20x109/L without transfusion for 7 days. Erythrocyte engraftment occurs much later and is characterized by independence from PRBC transfusions. Post-transplant cytopenias depend on conditioning regimen used, diagnosis and disease status, donor source, CD34+ cell dose in the allograft, use of growth factors, and GVHD prophylaxis.

Post-transplant (post-engraftment) Phase

Even after myeloid engraftment occurs the recipient remains immunosuppressed due to GVHD prophylaxis/treatment and slow immune reconstitution, which may take up to 12 months to occur. Notable complications during this phase include infections and GVHD and require continued monitoring. Immunosuppression withdrawal in the absence of GVHD is employed at this stage to facilitate immune reconstitution.

COMPLICATIONS

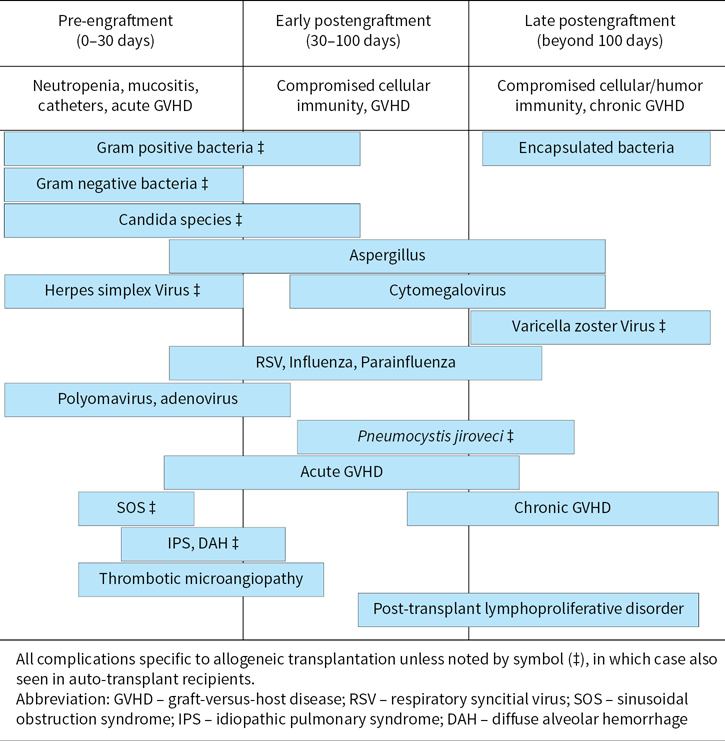

Figure 30.1 highlights the timeline for some important post-transplant complications after allo-HCT. The following text elaborates the salient features of some key adverse effects and may not be considered comprehensive.

FIGURE 30.1Timeline of complications after hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Graft Failure

Graft failure is a rare but serious complication characterized by the lack of engraftment and hematopoietic recovery after allo-HCT. Causes include HLA disparity, recipient alloimmunization, low CD34+ dose, T cell depletion of the graft, inadequate immunosuppression, disease progression, infections, and medications. Graft failure may be primary (early) when no hematopoietic recovery is noted post-HCT by day +28 or secondary (late) when the initial hematopoietic recovery is lost. Host immune mediated graft rejection is an important cause of graft failure. Growth factor support, manipulating dosage of immunosuppressive agents, CD34+ stem cell boost, DLI, and re-grafting represent approaches to the management of graft failure.

Infections

Infection remains a major cause of morbidity for patients undergoing HCT. Indwelling catheters and transmigration of intestinal flora are common sources of infections, and bacteremia and sepsis may occur during the pre-engraftment (neutropenic) phase of HCT. Current approaches to minimize the risk of life-threatening infections include the use of prophylactic antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral agents, as well as aggressive screening and treatment for common transplantation-associated infections.

(i)Cytomegalovirus—CMV infection most commonly occurs due to reactivation in seropositive patients or very rarely because of the transfer of an infection from the donor. The infection usually occurs after engraftment and may coincide with GVHD and/or its treatment. The risk for reactivation is highest up to day +100. CMV pneumonia and colitis can cause significant morbidity and mortality. In addition, it can cause febrile disease, hepatitis, and marrow suppression. Screening for viral reactivation is performed weekly after transplantation by measuring the CMV antigen levels or by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Initial treatment is with intravenous ganciclovir or oral valganciclovir ± intravenous immunoglobulin. Foscarnet and cidofovir are alternatives (especially in patients with cytopenias). The use of ganciclovir for the initial prophylaxis or preemptive therapy in patients who reactivate CMV post-transplant (i.e. become CMV-PCR +) can significantly prevent CMV disease and has resulted in a substantial reduction in CMV associated morbidity and mortality.

(ii)Invasive Fungal Infection—With the routine use of fluconazole prophylaxis in HCT patients, once lethal invasive Candida infections are relatively uncommon. Other important pathogens include Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Zygomycetes. Common presentations include pneumonia, rhinosinusitis, skin infections, or fungemia. Patients with GVHD on high dose steroids are especially at risk for invasive fungal infection and may benefit from expanded selection of antifungal prophylaxis.

(iii)Others—HSV and VZV reactivation is effectively prevented with acyclovir prophylaxis, but late VZV reactivation after cessation of prophylaxis has been noted. EBV reactivation and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders are seen more commonly with T-cell depleted transplants and in cord blood transplant recipients, especially those who receive anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG).

Sinusoidal Obstruction Syndrome (formerly veno-occlussive disease)

Hepatic SOS is characterized by jaundice, tender hepatomegaly, and unexplained weight gain or ascites and usually manifests in the first 2 weeks post-HCT. SOS is difficult to treat and typically involves supportive care measures focused on maintaining renal function, coagulation system, and fluid balance. The risk of SOS is higher in combination regimens containing alkylators with higher dose TBI or ablative doses of busulfan. The intravenous use and pharmacokinetic monitoring of busulfan drug levels has dramatically reduced the incidence of SOS. Defibrotide, a deoxyribonucleic acid derivative, which is an anticoagulant, was approved by the food and drug administration (FDA) in March 2016 for treatment of SOS.

Pulmonary Toxicity

Bacterial, viral, or fungal organisms may cause infectious pneumonia. Idiopathic pulmonary syndrome, characterized by fever, diffuse infiltrates, and hypoxia may occur in 10% of patients and has an abysmal prognosis in severe cases requiring ventilator support. A subset of patients with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage may respond to high-dose steroids. Other causes such as CMV pneumonitis, transfusion associated circulatory overload (TACO) and transfusion-associated lung injury (TRALI) must be excluded. Risk factors for pulmonary toxicity include ablative conditioning regimen (TBI), older age, prior radiation, a low DLCO, tobacco use, and GVHD.

Graft-versus-Host Disease

After allo-HCT, donor-derived T-lymphocytes may recognize recipient tissue as foreign and mount an immunologic attack resulting in GVHD. It is one of the main treatment-related toxicities and impacts NRM significantly. Conventionally acute GVHD was defined as occurring within day +100, and chronic GVHD beyond 100 days of transplant. It is no longer true and the classification should be based on clinical features rather than time of onset.

Acute GVHD: Up to 40% to 50% of MRD allo-HCT can be complicated by acute GVHD. Though varied in clinical presentation, it typically manifests in the first 2 to 6 weeks and affects the skin, liver, and the gastrointestinal system. The consensus criteria for staging/grading of acute GVHD is presented in Table 30.2. Risk factors for acute GVHD include degree of HLA mismatch, infections (CMV, VZV), unrelated donors, older patients, multiparous donor, older donors in MUD transplants, ABO-mismatches, sex-mismatched transplants (female donor → male recipients), and the use of intensive conditioning regimens.

Prevention of acute GVHD

Prevention of acute GVHD

Strategies to prevent acute GVHD have been established and are more effective than treating acute GVHD. Commonly employed strategies include the following:

1.Pharmacologic therapy: Combination therapy of non-specific immunosuppressive agents (methotrexate, steroids) and T-cell–specific immunosuppressant (calcineurin inhibitors—cyclosporine and tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil) is preferred to single agent therapy. Methotrexate IV on days +1, +3, +6, and +11 with tacrolimus or cyclosporine IV/PO starting day –2 is most commonly used. Sirolimus and mycophenolate are sometimes used in lieu of methotrexate. Drug toxicities and interactions are extremely important to monitor and drug levels are followed closely for calcineurin inhibitors and sirolimus.

2.T-cell depletion: Achieved by (a) ex vivo separation by CD34+ selection or the use of monoclonal antibodies to remove T cells or (b) in vivo T cell depletion with the use of monoclonal antibodies such as ATG or alemtuzumab or (c) the administration of post-transplant high cyclophosphamide. Though effective in reducing GVHD, these maneuvers may increase relapse rates and infections due to late immune reconstitution. In recent years the administration of post-transplantation cyclophosphamide, which mitigates the risk of GVHD by targeting alloreactive T-cells rapidly proliferating early after an HLA-mismatched transplant, has led to increased use of haploidentical-related donor transplants. The ongoing BMT CTN 1301 clinical trial is comparing this strategy to traditional GVHD prophylaxis and CD34+ selection in MRD and MUD allografts.

Treatment of acute GVHD

Treatment of acute GVHD

Frontline treatment for clinically significant (grades II–IV) acute GVHD is methylprednisolone at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day and calcineurin inhibitors should be continued or restarted. For those not responding or with partial response mycophenalate is usually added. Additional agents (azathioprine, daclizumab, photopheresis, ATG, infliximab) are used with variable success. Steroid refractory acute GVHD portends very poor prognosis. Prophylactic antifungal therapy against aspergillus should be considered in those on corticosteroid treatment.

Chronic GVHD: Use of PBPC allografts, MUD, and prior history of acute GVHD are risk factors. Chronic GVHD thought to be mediated chiefly by donor B-lymphocytes, presents with variable and multisystem organ involvement, and clinical manifestations may resemble autoimmune disorders (i.e., lichenoid skin changes, sicca syndrome, scleroderma-like skin changes, chronic hepatitis, and bronchiolitis obliterans). Chronic GVHD is often accompanied by cytopenias and immunodeficiency. Treatment involves prolonged courses of steroids and other immunosuppressive agents as well as prophylactic antibiotics (e.g., penicillin) and antifungal agents. Other potentially useful agents include thalidomide, mycophenolate mofetil, imatinib mesylate, pentostatin, rituximab, photopheresis, and Psoralen ultraviolet radiation (skin GVHD). More recently, B-cell receptor antagonist, ibrutinib (Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor), has shown clinical activity in Phase I/II trial which has prompted FDA to grant breakthrough status for patients with chronic GVHD not responding to initial therapy.

Relapse

Relapses after allo-HCT is ominous, especially for aggressive malignancies such as AML and ALL. Most relapses occur within 2 years of transplantation and those that relapse within 6 months have a worse prognosis. Immunosuppression is typically withdrawn to enhance GVT effect and, in some cases, DLI is administered. DLI administration frequently results in GVHD. The most favorable responses to DLI have been seen in patients with CML, especially those with molecular or chronic phase relapse. Second transplant for relapsed disease rarely results in long-term disease-free survival and is associated with a very high risk of NRM.

SURVIVORSHIP

It is estimated that there are over 125,000 patients who are long-term (>5 years) survivors after HCT. While survivors after auto-HCT lead near normal lives, studies have consistently shown that allograft recipients have lower life expectancy than age-matched population. Long-term complications depend on the conditioning regimen, age, and presence of chronic GVHD. Some key points are as follows:

1.Auto-HCT survivors are at risk for lung dysfunction, cardiovascular diseases, and secondary myelodysplasia/AML.

2.Major complications afflicting allo-HCT survivors include chronic GVHD, infections, organ dysfunction (pulmonary, cardiovascular, endocrine, and immune systems), secondary myelodysplasia/AML and solid organ malignancies. In addition, the pediatric population is at risk for growth retardation.

3.Immunizations are recommended for auto-HCT patients starting at 6 months and after withdrawal of immunosuppressive agents for allo-HCT. Long-term antibiotic prophylaxis is needed for patients receiving prolonged treatment for chronic GVHD.

4.Recommended screening and preventive measures for survivors have been established (see reference list). This include routine hemogram, hepatic, and renal function tests, endocrine screening (lipid panel, vitamin D, thyroid panel), immunological studies, and others studies (echocardiogram, pulmonary function tests, age appropriate cancer screening, ophthalmologic evaluation, bone densitometry)

CONCLUSION

Hematopoietic cell transplantation has evolved into an effective therapeutic option for a broad range of disease entities. The improved safety profile of the procedure and the increasing availability of donor sources have led to an increase in the number of transplants performed each year. There have been improvements in survival, less acute complications, and improved awareness and treatment of chronic complications. The number of patients who benefit from this procedure will likely increase as future transplantation strategies continue to evolve, minimizing adverse effects and expanding the stem cell source, while maximizing the beneficial effects donor immune-mediated GVT effects.

TABLE 30.1Common Indications for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Adults

Diagnosis | Autologous HCT | Allogeneic HCT |

Aplastic anemia | No | Yes |

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | No | Yes; CR1, Ph+ CR1, >CR2, Rel/Refa |

Acute myeloid leukemia | Yes; CR1a | Yes; High risk CR1, >CR2, Rel/Ref |

Chronic lymphoid leukemia | No | Yes |

Chronic myeloid leukemia | No | Yes; TKI intolerance/resistance, >CP1 |

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | Yes; 1st relapse/CR2 (chemosensitive) | Yes; >CR2, >2nd relapse, Ref |

Follicular lymphoma | Yes; 1st relapse/CR2 (chemosensitive) | Yes; >CR2, >2nd relapse, Ref |

Germ cell tumor (testicular) | Yes; Rela | No |

Hodgkin lymphoma | Yes; 1st relapse/CR2 (chemosensitive) | Yes; >CR2, >2nd relapse, Ref |

Mantle cell lymphoma | Yes; CR1 and >CR1 | Yes; >CR1 |

Multiple myeloma | Yes | Noa |

Myelodysplastic syndrome | No | Yes |

Myeloproliferative neoplasms | No | Yes |

T-cell lymphoma | Yes; CR1 and >CR1 | Yes; >CR1 |

aEither investigational or ideally considered as part of clinical trial.

HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; CR, complete remission; Ph, Philadelphia chromosome; Rel, relapsed; Ref, refractory; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; CP, chronic phase.

TABLE 30.2Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease Staging by Consensus Criteria

Stage | Skin | Liver (bilirubin) | Gastrointestinal (GI) |

0 | No skin rash | <2 mg/dL | <50 mL/d or persistent nausea alone |

1 | Maculopapular rash <25% BSA | 2.1–3 mg/dL | 500–1,000 mL/d, or persistent nausea, vomiting, anorexia, or positive upper GI biopsya |

2 | Maculopapular rash 25%–50% BSA | 3.1–6 mg/dL | 1,000–1,500 mL/d |

3 | Maculopapular rash >50% BSA | 6.1–15 mg/dL | >1,500 mL/d |

4 | Generalized erythroderma, plus bullae, or desquamation | >15 mg/dL | > 2000 mL/d, severe abdomen-al pain +/– ileus |

Clinical Grade | Skin | Liver | Gastrointestinal |

I | Stages 1–2 | None | None |

II | Stage 3 | Stage 1 | Stage 1 |

III | – | Stages 2–3 | Stages 2–4 |

IV | Stage 4 | Stage 4 | – |

amilliliter/day of liquid stool.

BSA, body surface area.

Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus conference on acute GVHD grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15(6):825–828.

Suggested Readings

1.Alousi AM, Bolaños-Meade J, Lee SJ. Graft-versus-Host Disease: The State of the Science. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. (0). Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1083879112004582.

2.Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, et al. Peripheral-Blood Stem Cells versus Bone Marrow from Unrelated Donors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(16):1487–1496.

3.Brunstein CG, Fuchs EJ, Carter SL, et al. Alternative donor transplantation after reduced intensity conditioning: results of parallel phase 2 trials using partially HLA-mismatched related bone marrow or unrelated double umbilical cord blood grafts. Blood. 2011;118(2):282–288.

4.Cantor AB, Lazarus HM, Laport G. Cellular basis of hematopoiesis and stem cell transplantation. In: American Society of Hematology - Self Assessment Program. 3rd ed. American Society of Hematology; 2010.

5.Copelan EA. Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(17):1813–1826.

6.Hamadani M, Craig M, Awan FT, Devine SM. How we approach patient evaluation for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45(8):1259–1268.

7.Horowitz MM, Confer DL. Evaluation of hematopoietic stem cell donors. ASH Education Program Book. 2005;2005(1):469–475.

8.Invaluable web resources for further reading: www.bethematch.org (National Marrow Donor Program), www.cibmtr.org (Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplantation), www.asbmt.org (American Society of Blood and Marrow Evaluation of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Donors Transplantation).

9.Majhail NS, Rizzo JD, Lee SJ, et al. Recommended screening and preventive practices for long-term survivors after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2012;18(3):348–371.

10.Rezvani A, Lowsky R, Negrin RS. Hematopoietic cell transplantation. In: Kaushansky K, Lichtman MA, Prchal JT, Levi M, Press O, Burns L, Caligiuri M, eds. Williams Hematology. 9th ed. The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2016.