Carcinoma of Unknown Primary 31

F. Anthony Greco

DEFINITION

Cancer of unknown primary (CUP) is a clinical pathologic syndrome defined by the presence of metastatic cancer in the absence of a clinically recognized anatomical primary site of origin.

Cancer of unknown primary (CUP) is a clinical pathologic syndrome defined by the presence of metastatic cancer in the absence of a clinically recognized anatomical primary site of origin.

CUP represents a heterogeneous group of different cancers, most with a very small (occult) primary tumor site, but with the capacity to metastasize. The pathologic diagnosis is made by biopsy of a metastasis.

CUP represents a heterogeneous group of different cancers, most with a very small (occult) primary tumor site, but with the capacity to metastasize. The pathologic diagnosis is made by biopsy of a metastasis.

Autopsy series of CUP patients revealed small invasive primary sites in 75% with more than 25 cancer types (mostly carcinomas) documented.

Autopsy series of CUP patients revealed small invasive primary sites in 75% with more than 25 cancer types (mostly carcinomas) documented.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

CUP is relatively common being among the ten most frequently diagnosed advanced cancers world-wide; estimated 50,000 patients annually in the United States.

CUP is relatively common being among the ten most frequently diagnosed advanced cancers world-wide; estimated 50,000 patients annually in the United States.

The exact incidence is not known since many CUP patients are arbitrarily assigned a specific primary site/cancer type based on the physician’s clinical opinion or pathology report despite the inability to detect an anatomical primary site and these cancers are not listed in tumor registries as CUP.

The exact incidence is not known since many CUP patients are arbitrarily assigned a specific primary site/cancer type based on the physician’s clinical opinion or pathology report despite the inability to detect an anatomical primary site and these cancers are not listed in tumor registries as CUP.

Male to female ratio is about 1.2 to 1.

Male to female ratio is about 1.2 to 1.

The cause of the CUP syndrome remains an enigma. The clinically occult invasive primaries metastasize and metastases grow and become clinically detectable. Acquired genetic and/or epigenetic alterations are likely to be the basis of the syndrome. However, no specific unique nonrandom genetic alterations have yet been discovered.

The cause of the CUP syndrome remains an enigma. The clinically occult invasive primaries metastasize and metastases grow and become clinically detectable. Acquired genetic and/or epigenetic alterations are likely to be the basis of the syndrome. However, no specific unique nonrandom genetic alterations have yet been discovered.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND PROGNOSIS

Nearly all patients have symptoms related to metastasis, which can be present at any site, but are most common in lymph nodes, liver, lungs, and bones.

Nearly all patients have symptoms related to metastasis, which can be present at any site, but are most common in lymph nodes, liver, lungs, and bones.

CUP is not a single cancer type, but many specific metastatic cancers, which have a common unique feature—an occult clinically undetectable invasive anatomical primary site.

CUP is not a single cancer type, but many specific metastatic cancers, which have a common unique feature—an occult clinically undetectable invasive anatomical primary site.

Most CUP patients (greater than 50%) present with multiple sites of metastasis but a minority have only 1 to 2 sites. Although metastatic sites are occasionally atypical for the primary, most CUP cancers metastasize to sites expected for the primary and are otherwise biologically similar to their counterparts with known primaries. The major difference in CUP cancers and metastasis from a known primary cancer appears to be the size of the primary site.

Most CUP patients (greater than 50%) present with multiple sites of metastasis but a minority have only 1 to 2 sites. Although metastatic sites are occasionally atypical for the primary, most CUP cancers metastasize to sites expected for the primary and are otherwise biologically similar to their counterparts with known primaries. The major difference in CUP cancers and metastasis from a known primary cancer appears to be the size of the primary site.

In the past all patients were grouped together since the specific type or origin of the cancer was not definable; CUP was considered as a single entity assumed to be biologically similar; a minority (about 15%) of patients were eventually defined within several favorable subsets based on clinicopathologic features (discussed later).

In the past all patients were grouped together since the specific type or origin of the cancer was not definable; CUP was considered as a single entity assumed to be biologically similar; a minority (about 15%) of patients were eventually defined within several favorable subsets based on clinicopathologic features (discussed later).

In general, when CUP patients are treated with nonspecific empiric chemotherapy their median survival time (excluding the favorable subsets) is about 9 months with a 1-year survival of 25% and 5-year survival less than 10%.

In general, when CUP patients are treated with nonspecific empiric chemotherapy their median survival time (excluding the favorable subsets) is about 9 months with a 1-year survival of 25% and 5-year survival less than 10%.

Poor prognostic factors in the past were largely determined from untreated patients or those treated with empiric chemotherapy in the era when the specific cancer type was not possible to define.

Poor prognostic factors in the past were largely determined from untreated patients or those treated with empiric chemotherapy in the era when the specific cancer type was not possible to define.

Historically poor prognostic factors included men, adenocarcinoma histology, increasing number of metastasis to multiple organ sites, hepatic or adrenal involvement, poor performance status, high serum LDH, and low serum albumin; many of these factors also apply to patients with many types of advanced cancer.

Historically poor prognostic factors included men, adenocarcinoma histology, increasing number of metastasis to multiple organ sites, hepatic or adrenal involvement, poor performance status, high serum LDH, and low serum albumin; many of these factors also apply to patients with many types of advanced cancer.

Patients with more favorable prognostic factors included favorable clinical pathologic subsets (discussed later), predominant lymph node involvement without major visceral involvement.

Patients with more favorable prognostic factors included favorable clinical pathologic subsets (discussed later), predominant lymph node involvement without major visceral involvement.

DIAGNOSIS

The initial diagnostic evaluation recommended is outlined in Table 31.1. If an anatomical primary site is identified the patient does not have CUP.

The initial diagnostic evaluation recommended is outlined in Table 31.1. If an anatomical primary site is identified the patient does not have CUP.

Biopsy samples should be generous if possible, avoiding fine needle aspirations since several tests may be necessary. The first goal is confirming the diagnosis of cancer and second goal the specific type of cancer.

Biopsy samples should be generous if possible, avoiding fine needle aspirations since several tests may be necessary. The first goal is confirming the diagnosis of cancer and second goal the specific type of cancer.

Standard pathologic examination including immunohistochemical (IHC) staining is routinely done on CUP biopsies.

Standard pathologic examination including immunohistochemical (IHC) staining is routinely done on CUP biopsies.

Table 31.2 lists some of the useful IHC staining patterns, but the selection of stains is often based on the light microscopic histopathological appearance of the biopsy and clinical features; obtaining multiple stains indiscriminately exhausts the biopsy specimen and rarely improves the diagnostic ability.

Table 31.2 lists some of the useful IHC staining patterns, but the selection of stains is often based on the light microscopic histopathological appearance of the biopsy and clinical features; obtaining multiple stains indiscriminately exhausts the biopsy specimen and rarely improves the diagnostic ability.

Additional evaluation recommended based on the initial findings is outlined in Table 31.3.

Additional evaluation recommended based on the initial findings is outlined in Table 31.3.

The lineage of the cancer (carcinoma, sarcoma, melanoma, lymphoma) is usually diagnosed by light microscopic appearance and if necessary by IHC staining.

The lineage of the cancer (carcinoma, sarcoma, melanoma, lymphoma) is usually diagnosed by light microscopic appearance and if necessary by IHC staining.

Molecular cancer classifier assays have been developed based on gene expression profile patterns and are a major advance in the diagnosis of the cancer type in CUP patients. In the United States there are three commercially available assays (BioTheranostics, Inc. Cancer TYPE ID, a 92 gene RT-PCR assay that provides a molecular classification of 50 cancer types/subtypes with an overall 87% accuracy; Cancer Genetics, Inc. Tissue of Origin test, a 2000 gene microarray assay that identifies 15 cancer types with an 89% accuracy; Rosetta Genomics (Cancer Origin Assay) which is a microarray, micro RNA assay with about a 90% accuracy which can identify 49 cancer types.)

Molecular cancer classifier assays have been developed based on gene expression profile patterns and are a major advance in the diagnosis of the cancer type in CUP patients. In the United States there are three commercially available assays (BioTheranostics, Inc. Cancer TYPE ID, a 92 gene RT-PCR assay that provides a molecular classification of 50 cancer types/subtypes with an overall 87% accuracy; Cancer Genetics, Inc. Tissue of Origin test, a 2000 gene microarray assay that identifies 15 cancer types with an 89% accuracy; Rosetta Genomics (Cancer Origin Assay) which is a microarray, micro RNA assay with about a 90% accuracy which can identify 49 cancer types.)

Data are accumulating for these three molecular cancer classifier assays as well as a new DNA-based epigenetic assay (EPICUP) also demonstrating about a 90% accuracy.

Data are accumulating for these three molecular cancer classifier assays as well as a new DNA-based epigenetic assay (EPICUP) also demonstrating about a 90% accuracy.

The diagnostic ability of the combination of IHC and molecular cancer classifiers often provides critical information to plan appropriate treatment for each patient.

The diagnostic ability of the combination of IHC and molecular cancer classifiers often provides critical information to plan appropriate treatment for each patient.

TABLE 31.1Initial Diagnostic Evaluation of a Possible CUP Patient

|

|

TABLE 31.2IHC Staining Patterns Characteristic of a Single Cancer or Tissue of Origina

Prostate | CK7–, CK20–, PSA+ |

Breast | CK7+, CK20–, GCDFP-15+, mammoglobin+, ER+,PR+, GATA3+ Her-2-neu+ |

Lung-adenocarcinoma and large cell | CK7+, CK20– TTF-1+, Napsin A+ |

Colorectal | CK7–, CK20+, CDX2+ |

Germ cell | PLAP+,OCT4+, SALL4+ |

Lung-Neuroendocrine (small cell/large cell) | Chromogranin+, synaptophysin+, CD56+, TTF-1+ |

Thyroid carcinoma (papillary/follicular) | Thyroglobin+, TTF-1+ |

Melanoma | MelanA+, HMB45+, S100+ |

Adrenal carcinoma | Alpha-inhibin+, Melan-A+(A103) |

Renal cell carcinoma | RCC+, PAX8+ |

Ovary carcinoma | CK7+, CK20–, WT-1+, PAX8+, ER+ |

Hepatocellular carcinoma | Hepar-1+, CD10+, CD13+ |

a In the appropriate clinical and pathologic setting the staining profiles may be diagnostic of the tissue of origin or cancer type. Stains frequently overlap and not all are always positive or negative as indicated above.

Table 31.3Additional Evaluation Based on Findings from Initial Diagnostic Evaluation in CUP

Results of Initial Diagnostic Evaluation | Additional Evaluation | |

Clinical | IHC Staining/Other Testing | |

Features highly suggestive of colorectal carcinoma (peritoneal/liver metastasis; biopsy CK20+, CK7–, CDX2+) | Colonoscopy | KRAS mutation of biopsy |

Features highly suggestive of lung carcinoma (mediastinal/hilar adenopathy; biopsy CK7+, CK20–, TTF-1+) | Consider bronchoscopy | Genomic analysis of biopsy for EGFR mutation and ALK/ROS1 rearrangement |

Features suggestive of ovarian carcinoma (peritoneal/pelvic metastasis; biopsy CK7+) | Intravaginal/pelvic ultrasound | WT-1, PAX8, andER stains of biopsy |

Features suggestive of breast carcinoma (axillary nodes, lung, bone, liver metastasis; CK7+) | Breast MRI | ER, GCDFP-15, mammoglobin, and GATA3 stains; Her-2-neu testing of biopsy |

Mediastinal and/or retroperitoneal masses in young adults (usually men) | Testicular ultrasound, serum AFP, HCG, and LDH | PLAP,OCT4, SALL4 stains of biopsy; FISH for i(12)p of biopsy |

Poorly differentiated carcinoma, with or without clear cell features | Serum AFP if liver involvement; octreotide scan if neuroendocrine stains+ | Chromogranin, synaptophysin, RCC, PAX8, Hepar1, MelanA, and HMB-45 stains of biopsy |

Liver lesions predominant (CK7-,CK20-) | Serum AFP | Hepar1 stain of biopsy |

Any histology without a single cancer site or tissue of origin predicted by IHC or small amount of biopsy | Molecular cancer classifier assay of biopsy | |

HISTOLOGIC/MORPHOLOGIC CELL TYPES

The light microscopic classification of CUP includes several recognized histologic types including adenocarcinoma (60%), poorly differentiated carcinoma with some features of adenocarcinoma (30%), squamous cell carcinoma (5%), neuroendocrine carcinomas (3%), and poorly differentiated neoplasm with confusing or undefined lineage (2%). Occasionally, melanoma or sarcoma presents as CUP and generally are treated with site specific therapies and not further discussed in this brief review.

The light microscopic classification of CUP includes several recognized histologic types including adenocarcinoma (60%), poorly differentiated carcinoma with some features of adenocarcinoma (30%), squamous cell carcinoma (5%), neuroendocrine carcinomas (3%), and poorly differentiated neoplasm with confusing or undefined lineage (2%). Occasionally, melanoma or sarcoma presents as CUP and generally are treated with site specific therapies and not further discussed in this brief review.

Segregation of the above histologic types is important since various favorable subsets could be more easily recognized. Over the past four decades, several favorable subsets (15% of all CUP patients) are now treated with site-specific therapy based on their presumed tissue of origin (discussed later).

Segregation of the above histologic types is important since various favorable subsets could be more easily recognized. Over the past four decades, several favorable subsets (15% of all CUP patients) are now treated with site-specific therapy based on their presumed tissue of origin (discussed later).

The majority of CUP patients (85%) are not included in any of the favorable subsets, and there does not appear to be any prognostic significance of the light microscopic histology.

The majority of CUP patients (85%) are not included in any of the favorable subsets, and there does not appear to be any prognostic significance of the light microscopic histology.

Nonspecific empiric chemotherapy regimens were developed in large part from 1995 through 2006 and the 85% of CUP patients with unfavorable prognostic features were usually treated; the cancer type could not be determined in most patients and the same empiric chemotherapy regimens were used for all patients assuming all CUP cancers were biologically similar. Although these empiric regimens helped a minority of patients, the overall median survival in larger series (greater than 100 patients) has been only about 9 months.

Nonspecific empiric chemotherapy regimens were developed in large part from 1995 through 2006 and the 85% of CUP patients with unfavorable prognostic features were usually treated; the cancer type could not be determined in most patients and the same empiric chemotherapy regimens were used for all patients assuming all CUP cancers were biologically similar. Although these empiric regimens helped a minority of patients, the overall median survival in larger series (greater than 100 patients) has been only about 9 months.

FAVORABLE SUBSETS OF CUP PATIENTS

Clinical features including gender, metastatic sites, and histologic classification of these cancers and more recently IHC and molecular cancer classifier assays have provided the basis to presume a specific primary tumor or cancer type for selected patients. Treatment based upon these presumptive diagnoses has generally improved the overall outcome of these patient subsets (see Table 31.4.) Recent data reveal the cancer types of many of the favorable CUP subsets reported several years ago are as expected based on IHC staining and/or molecular cancer classifier assays.

TABLE 31.4Favorable Subsets of CUP

Subset | Therapy |

A.Young men (rarely women) retroperitoneal and/or mediastinal masses; serum | Treat as germ cell carcinoma |

B.Squamous cell carcinoma in cervical/neck nodes | Treat as head/neck carcinoma |

C.Squamous cell carcinoma in inguinal/iliac nodes | Treat as anal, cervical, or vulvar carcinoma |

D.Women (rarely men) with axillary carcinoma | Treat as breast carcinoma |

E.Women (rarely men) with peritoneal carcinoma (usually serous adenocarcinoma) | Treat as ovarian carcinoma |

F.Neuroendocrine carcinoma | |

Well differentiated | Treat like carcinoid |

Poorly differentiated | Treat like small cell lung carcinoma |

G.Men with osteoblastic bone metastasis-PSA+ | Treat like prostate carcinoma |

H.CUP colorectal subset (IHC and/or molecular cancer classifier assay diagnosis of colorectal) | Treat like colorectal carcinoma. |

I.Single small site of metastasis | Treat with surgery and/or RT; chemotherapy |

J.Poorly differentiated neoplasms (linage unknown) | Many responsive neoplasms (further evaluation critical) |

K.Isolated pleural effusion with carcinoma | Many responsive carcinomas (further evaluation critical) |

L. Gestational carcinoma serum B-HCG elevated | Treat as gestational choriocarcinoma |

A.Extragonadal germ cell cancer syndrome

•These patients represent a rare, but important subset, since they have very treatable and potentially curable advanced cancers if recognized and treated appropriately.

•Most commonly these tumors are found in young men, but also even more rarely in women. These carcinomas usually involve the midline location (mediastinum and/or retroperitoneum) and/or multiple lung nodules.

•The histology of the biopsy is usually a poorly differentiated carcinoma or poorly differentiated neoplasm.

•Elevated serum levels of beta HCG and/or alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) are commonly seen.

•IHC staining for germ cell tumors and/or a molecular cancer classifier assay or FISH testing for an isochromosome of 12 may be diagnostic.

•Therapy for germ cell carcinomas is indicated even if the histology is atypical which is characteristic in these patients.

B.Axillary carcinoma in women and rarely men

•Most of these patients have occult breast carcinoma.

•IHC stains are usually positive for breast markers, but some are triple negative; molecular classifiers assays usually predict breast carcinoma.

•Mammography is negative; breast MRI and PET scans detect some small primaries.

•If mastectomy is done, about 60% have documented small invasive primary breast carcinomas. It is possible that many others also have a very small primary, but are missed as it may take hundreds of tissue sections to find a very small clinically occult invasive primary.

•Treatment guidelines should be similar to stage II or III breast carcinoma; primary radiotherapy of the ipsilateral breast is an acceptable alternative to surgery; neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy and/or hormone therapy as per breast cancer guidelines is indicated.

•The prognosis of these patients appear similar to women with known stage II or III breast cancer when they are treated appropriately.

•In patients with an axillary mass and other metastasis, the suspicion of occult breast cancer should remain high.

C.Squamous cell carcinoma in upper cervical/neck nodes

•Highly suggests an occult head and neck carcinoma.

•PET scanning reveals the primary site in more than one-third of these patients, despite the inability to find it by any other testing.

•Human papillomavirus (HPV) association is common.

•Treatment with combined modality chemotherapy and radiotherapy as per head and neck carcinoma and outcomes similar.

D.Squamous cell carcinoma in inguinal or pelvic lymph nodes

•Most likely arising from an occult primary from the uterine cervix, anal canal, or more rarely the vulva or skin. HPV association is seen with both cervical and anal cell carcinomas.

•Potentially curable cancers with combined modality therapy.

E.Peritoneal carcinoma in women and rarely men

•They usually have serous adenocarcinoma but may be poorly differentiated carcinoma; these tumors are more common in BRCA1/2 germline mutation patients.

•IHC staining and/or molecular classifier assays usually consistent with ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal carcinoma.

•Serum CA 125 often elevated but not specific.

•Treatment should be similar to stage III ovarian carcinoma and the outcomes are similar.

F.Neuroendocrine carcinoma

•An important distinction is the grade of the tumor—well differentiated or poorly differentiated; some poorly differentiated carcinomas are not recognized as neuroendocrine unless specific IHC stains and/or a molecular cancer classifier assay are obtained.

•Well-differentiated tumors have a similar biology to well-differentiated carcinoid or islet cell tumors.

•Treatment for well-differentiated tumors is similar to advanced carcinoid tumors; overall prognosis fair to good in part due to the indolent nature of these cancers and the evolving improving therapies.

•Treatment for high grade or poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumor should be similar to small cell lung cancer or extra-pulmonary small cell carcinomas with cisplatin- or carboplatin-based chemotherapy; radiotherapy should be added in those with local regional involvement.

•A small percentage (about 10%) of patients with poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors have long-term survival following combination chemotherapy including etoposide and platinum (most other patients have responses to chemotherapy with improvement in the quality and quantity of life).

G.Men with elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) or osteoblastic metastasis

•Hormonal therapy for prostate carcinoma should be administered when the serum PSA is elevated (serum PSA recommended for all men with CUP) or tumor PSA stain is positive. Men with osteoblastic metastasis warrant a trial of hormone therapy in selected clinical settings regardless of the PSA level. A molecular cancer classifier assay may also help with the diagnosis.

H.Single small site of metastasis

•Local therapy with surgical resection and/or radiotherapy.

•Site specific therapy should be considered depending on the determination of the cancer type by immunostaining and/or a molecular cancer classifier assay.

I.Poorly differentiated neoplasms

•About 2% of all CUP patients have a poorly differentiated neoplasm without a definitive lineage by light microscopic examination; after IHC staining only a small minority of these cancers remain undefined; in this group a molecular cancer classifier has been proven to be useful in the majority of patients.

•Precise diagnosis in these patients is important by the appropriate use of IHC staining panels and if necessary a molecular cancer classifier assay (several of these patients have highly treatable neoplasms including germ cell tumors, lymphoma, melanomas, and others).

J.CUP colorectal subset

•A subset of CUP patients with IHC stains and or a molecular cancer classifier assay diagnostic of a lower GI primary have improved outcomes with median survivals about 24 months similar to known colorectal adenocarcinomas when treated with colorectal site specific regimens.

•These patients do not have their primary sites found at colonoscopy and most have metastasis typical for colorectal primaries (liver, peritoneal cavity, retroperitoneal nodes).

•These CUP patients should be treated in a similar fashion as known metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma since their outcome is improved.

K.Amelanotic melanoma

•Melanoma has been known for decades by pathologists as the “great imitator”; the histology can be confusing, particularly when no melanin pigment is identified in the cancer cells; melanoma may appear as a poorly differentiated carcinoma or the lineage may not be recognized.

•Appropriate IHC stains usually are diagnostic, but if there is a doubt a molecular cancer classifier assay is usually helpful.

•Treatment implications are obvious since BRAF inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors often provide useful therapy.

L.Isolated pleural effusion

•This subset is recognized with an overall better prognosis than those with multiple metastasis.

•A small peripheral lung carcinoma obscured by fluid should be suspected but occult breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and other occult primaries may present with metastasis and isolated pleural effusion; nonspecific empiric chemotherapy has been useful for some of these patients in the past, but specialized pathology with appropriate IHC stains and if necessary a molecular cancer classifier assay is indicated to direct site specific therapy for these patients.

M.Unrecognized gestational choriocarcinoma

•CUP in a young woman with poorly differentiated carcinoma or neoplasm particularly during pregnancy or in the postpartum period or after spontaneous abortion should be suspected of harboring gestational choriocarcinoma; examination of the placenta or other tissue is usually diagnostic.

•A serum beta HCG is always elevated and chemotherapy for choriocarcinoma is usually curative; in the gestational setting choriocarcinoma is most likely but an elevated serum beta HCG may also be from a germ cell carcinoma.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES, EVALUATION, AND TREATMENT OF CUP PATIENTS

The goal in any patient with metastatic cancer is to determine the primary site or cancer type.

The goal in any patient with metastatic cancer is to determine the primary site or cancer type.

Therapy is based upon an accurate identification of the precise cancer type.

Therapy is based upon an accurate identification of the precise cancer type.

In patients with CUP an anatomical primary site is not clinically identified after a reasonable evaluation; determination of the cancer type depends on considering all clinicopathologic data, but particularly IHC staining panels and if necessary a molecular cancer classifier assay performed on a biopsy of a metastatic lesion.

In patients with CUP an anatomical primary site is not clinically identified after a reasonable evaluation; determination of the cancer type depends on considering all clinicopathologic data, but particularly IHC staining panels and if necessary a molecular cancer classifier assay performed on a biopsy of a metastatic lesion.

Molecular cancer classifier assays have been proven to diagnose the cancer type in CUP in about 95% of patients.

Molecular cancer classifier assays have been proven to diagnose the cancer type in CUP in about 95% of patients.

Data from several prospective and retrospective studies now support the use of molecular cancer classifier assays in the majority of patients (about 66%) who are not diagnosed with a single cancer type by IHC staining panels.

Data from several prospective and retrospective studies now support the use of molecular cancer classifier assays in the majority of patients (about 66%) who are not diagnosed with a single cancer type by IHC staining panels.

Once the cancer type in CUP is diagnosed, site-specific therapy for that cancer should be administered since data shows an improved outcome for many patients compared to nonspecific empiric chemotherapy, which was the standard in the past.

Once the cancer type in CUP is diagnosed, site-specific therapy for that cancer should be administered since data shows an improved outcome for many patients compared to nonspecific empiric chemotherapy, which was the standard in the past.

Precision or personalized therapy is now indicated for CUP patients based on the recognition of the cancer. CUP is not a single cancer and each patient has a specific cancer and therapy is indicated for their cancer type. For some cancer types (including breast, lung, colorectal, ovary renal, and others) several site-specific therapies, in some instances used sequentially, improve patient survival; the effectiveness and outcomes is variable and better for patients with cancers known to be responsive to therapies; the presence of genetic alterations which are successfully targeted by various drugs now also have proven survival benefit for some patients with lung, melanoma, breast, GE junction/gastric, colorectal, and other cancers. The recognition of the usefulness of immune checkpoint inhibitors in several patients with a number of advanced cancers also makes the precise diagnosis of the cancer type important.

Precision or personalized therapy is now indicated for CUP patients based on the recognition of the cancer. CUP is not a single cancer and each patient has a specific cancer and therapy is indicated for their cancer type. For some cancer types (including breast, lung, colorectal, ovary renal, and others) several site-specific therapies, in some instances used sequentially, improve patient survival; the effectiveness and outcomes is variable and better for patients with cancers known to be responsive to therapies; the presence of genetic alterations which are successfully targeted by various drugs now also have proven survival benefit for some patients with lung, melanoma, breast, GE junction/gastric, colorectal, and other cancers. The recognition of the usefulness of immune checkpoint inhibitors in several patients with a number of advanced cancers also makes the precise diagnosis of the cancer type important.

CUP patients have a large range of cancer types arising from many occult anatomically undetectable primaries and some, particularly with the more responsive cancers, may be treated effectively if recognized.

CUP patients have a large range of cancer types arising from many occult anatomically undetectable primaries and some, particularly with the more responsive cancers, may be treated effectively if recognized.

A small minority of CUP patients (about 5%) cannot have their precise cancer type identified despite the use of appropriate IHC panels and molecular cancer classifier assays; nonspecific empiric chemotherapy is appropriate in these patients.

A small minority of CUP patients (about 5%) cannot have their precise cancer type identified despite the use of appropriate IHC panels and molecular cancer classifier assays; nonspecific empiric chemotherapy is appropriate in these patients.

Examples of four frequently used empiric regimens for CUP including high grade neuroendocrine carcinoma are illustrated in Table 31.5.

Examples of four frequently used empiric regimens for CUP including high grade neuroendocrine carcinoma are illustrated in Table 31.5.

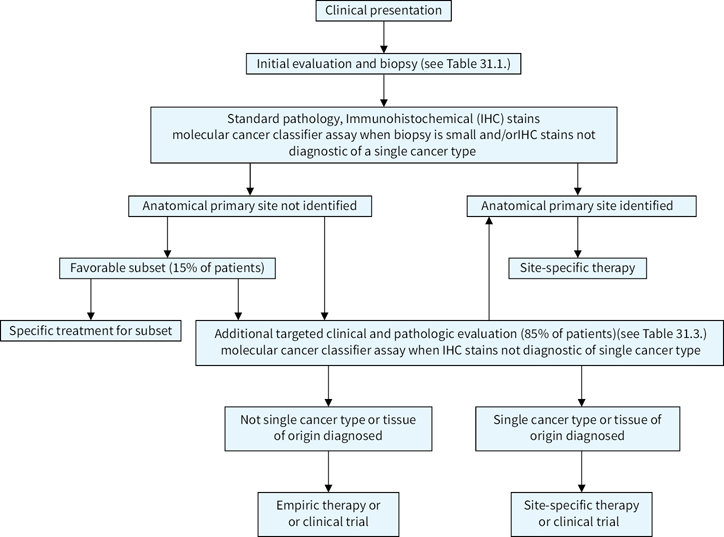

The suggested algorithm for the management of a possible CUP patient is illustrated in Figure 31.1.

The suggested algorithm for the management of a possible CUP patient is illustrated in Figure 31.1.

TABLE 31.5Empiric Chemotherapy Commonly Used in the Past for Carcinoma of Unknown Primary

Adenocarcinoma or poorly differentiated carcinoma | |

Paclitaxel | 200 mg/m2 IV day 1 |

Carboplatin | AUC 6 IV day1 |

Repeat cycle 3 weeks | |

6 cycles | |

Gemcitibine, | 1,250 mg/m2 IV days 1,8 |

Cisplatin | 80–100 mg/m2 day 1 Repeat cycle 3 weeks |

6 cycles | |

High grade neuroendocrine carcinoma | |

Etoposide | 100 mg/m2 IV days 1,2,3 |

Carboplatin | AUC 5 IV day 1 |

Repeat cycle 3 weeks | |

4–6 cycles | |

Etoposide | 100 mg/m2 IV days 1,2,3 |

Cisplatin | 80–100 mg/m2 IV day 1 |

Repeat cycle 3–4 weeks | |

4–6 cycles | |

Suggested Readings

1.Ettinger DS, Handorf CR, Agulnik M, et al. Occult primary, Version 3.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:969–974.

2.Greco FA, Hainsworth JD. Cancer of unknown primary site. In: DeVita VT Jr., Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, eds. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology.10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Publishers; 2015:1720–1737.

3.Greco FA, Lennington WJ, Spigel DR, Hainsworth JD. Molecular profiling diagnosis in unknown primary cancer: accuracy and ability to complement standard pathology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:782–790.

4.Greco FA, Lennington WJ, Spigel DR, Hainsworth JD. Poorly differentiated neoplasms of unknown primary site; diagnostic usefulness of a molecular cancer classifier assay. Mol Diagn Ther. 2015;19:91–97.

5.Greco FA. Cancer of unknown primary site: still an entity, a biological mystery and a metastatic model. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14;3–4.

6.Greco FA. Molecular diagnosis of the tissue of origin in cancer of unknown primary site: useful in patient management. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2013;14:634–642.

7.Hainsworth JD, Greco FA. Gene expression profiling in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site; from translational research to standard of care. Virchows Arch. 2014;464:393–402.

8.Hainsworth JD, Rubin MS, Spigel DR, et al. Molecular gene expression profiling to predict the tissue of origin and direct site-specific therapy in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site: a prospective trial of the Sarah Cannon Research Institute. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:217–223.

9.Moran S, Martinez-Cardus A, Sayols S, et al. Epigenetic profiling to classify cancer of unknown primary: a multicentre, retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1386–1385.

10.Oien KA, Dennis JL. Diagnostic work-up of carcinoma of unknown primary: from immunohistochemistry to molecular profiling. Ann. Oncol. 2012;23:271–277.

11.Pentheroudakis G, Golfinopoulos V, Pavlidis N. Switching benchmarks in cancer of unknown primary from autopsy to microarray. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2026–2036.

12.Varadhachary GR, Karanth S, Qiao W, et al. Carcinoma of unknown primary with gastrointestinal profile: immunohistochemistry and survival data for this favorable subset. Int J Clin Oncol. 2014;19:479–484.

13.Varadhachary GR, Raber MN. Carcinoma of unknown primary site. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:757–765.

14.Yoon HH, Foster NR, Meyers JP, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies responsive patients with cancer of unknown primary treated with carboplatin, paclitaxel, and everolimus: NCCTG No871(alliance). Ann Oncol. 2016;27:339–344.