Christina Tafe, Jean-Paul Pinzon, and Ann Berger

DEFINITIONS

Palliative care is based on a holistic model of symptom management. It concerns improving the quality of life for patients and their families facing life-threatening or terminal illnesses by preventing, identifying, and relieving suffering associated with physical, psychosocial, and spiritual problems.

Palliative care is based on a holistic model of symptom management. It concerns improving the quality of life for patients and their families facing life-threatening or terminal illnesses by preventing, identifying, and relieving suffering associated with physical, psychosocial, and spiritual problems.

Concurrent palliative care involvement adds benefit to the oncology patient by managing symptoms of disease and treatment early to promote compliance of treatment and maintain quality of life while disease modifying treatments are rendered.

Concurrent palliative care involvement adds benefit to the oncology patient by managing symptoms of disease and treatment early to promote compliance of treatment and maintain quality of life while disease modifying treatments are rendered.

A breakthrough study published in 2010 looked at early integration of palliative care in the treatment of metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer patients and found that patients receiving early palliative care, as compared with those receiving standard care alone, had improved survival (Temel et al., 2010).

A breakthrough study published in 2010 looked at early integration of palliative care in the treatment of metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer patients and found that patients receiving early palliative care, as compared with those receiving standard care alone, had improved survival (Temel et al., 2010).

Pain is a common referral for palliative care consultation and is usually, but not always, associated with tissue damage. It is always subjective and may be influenced by emotional, psychological, social, and spiritual factors, as well as financial concerns and fear of death. This is referred to as “total pain” and is best treated with an interdisciplinary approach to address all areas of suffering for patient and family.

Pain is a common referral for palliative care consultation and is usually, but not always, associated with tissue damage. It is always subjective and may be influenced by emotional, psychological, social, and spiritual factors, as well as financial concerns and fear of death. This is referred to as “total pain” and is best treated with an interdisciplinary approach to address all areas of suffering for patient and family.

Acute pain is the predictable physiologic response to an adverse chemical, thermal, or mechanical stimulus. It is normally associated with surgery, trauma, and acute illness. It is generally time limited and responsive to a variety of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies.

Acute pain is the predictable physiologic response to an adverse chemical, thermal, or mechanical stimulus. It is normally associated with surgery, trauma, and acute illness. It is generally time limited and responsive to a variety of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies.

When acute pain persists over time, it is classified as chronic pain.

When acute pain persists over time, it is classified as chronic pain.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Most cancer patients experience some degree of pain, especially in the advanced and metastatic phases of disease. In advanced cancer, the prevalence of pain is about 70%, but varies with the type and stage of disease.

Most cancer patients experience some degree of pain, especially in the advanced and metastatic phases of disease. In advanced cancer, the prevalence of pain is about 70%, but varies with the type and stage of disease.

There are several published guidelines for cancer pain management recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), and effective treatments are available for 70% to 90% of cases.

There are several published guidelines for cancer pain management recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), and effective treatments are available for 70% to 90% of cases.

Nevertheless, an estimated 40% of cancer patients remain undertreated for reasons related to the health care provider, the patient and family, or cultural mores. The most frequent cause of under treatment is misconceptions about the use of opioids.

Nevertheless, an estimated 40% of cancer patients remain undertreated for reasons related to the health care provider, the patient and family, or cultural mores. The most frequent cause of under treatment is misconceptions about the use of opioids.

ASSESSMENT

Proper pain assessment can help to establish a good doctor/patient relationship, guide the therapeutic regimen, improve pain management, maximize patient comfort and function, and increase patient satisfaction with therapy. Failure to fully assess pain in the cancer patient may result in adverse pain outcomes, regardless of the amount or type of analgesia and adjuvants used.

Proper pain assessment can help to establish a good doctor/patient relationship, guide the therapeutic regimen, improve pain management, maximize patient comfort and function, and increase patient satisfaction with therapy. Failure to fully assess pain in the cancer patient may result in adverse pain outcomes, regardless of the amount or type of analgesia and adjuvants used.

Patients’ self-reports should be the main source of pain assessment. For infants and the cognitively impaired, physicians can utilize nonverbal pain scales (PAIN-AD, Wong-Baker Faces, CNVI) (Quill et al., 2010).

Patients’ self-reports should be the main source of pain assessment. For infants and the cognitively impaired, physicians can utilize nonverbal pain scales (PAIN-AD, Wong-Baker Faces, CNVI) (Quill et al., 2010).

Patients should be reassessed frequently by inquiring how much their pain has been relieved after each treatment. A consistent disparity between patients’ self-report of pain and their ability to function necessitates further assessment to ascertain the reason for the disparity.

Patients should be reassessed frequently by inquiring how much their pain has been relieved after each treatment. A consistent disparity between patients’ self-report of pain and their ability to function necessitates further assessment to ascertain the reason for the disparity.

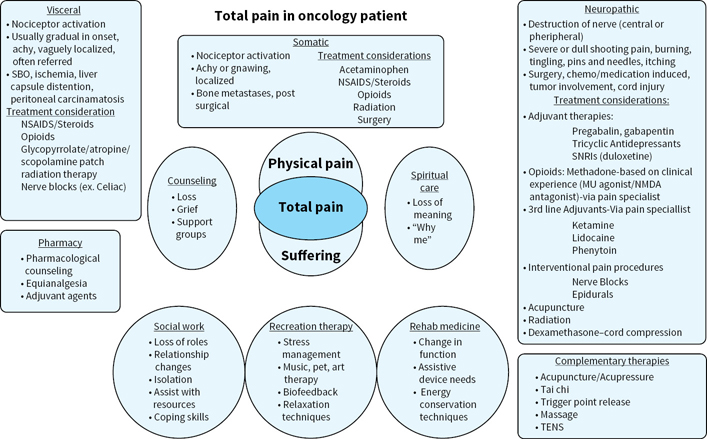

When addressing total pain, it is important to look at other forms of suffering and appropriate treatments in addition to physical suffering to ensure that medication management such as opioids are not over or underutilized for management of the oncology patient. (Fig. 40.1)

When addressing total pain, it is important to look at other forms of suffering and appropriate treatments in addition to physical suffering to ensure that medication management such as opioids are not over or underutilized for management of the oncology patient. (Fig. 40.1)

FIGURE 40.1Total pain in oncology patient.

TREATMENT

Treatment of physical pain should be tailored to each patient, based on the type of pain and duration of expected pain. (Somatic, visceral, neuropathic, and acute vs. chronic).

Treatment of physical pain should be tailored to each patient, based on the type of pain and duration of expected pain. (Somatic, visceral, neuropathic, and acute vs. chronic).

Use an interdisciplinary team to assist with suffering to improve management of the patient’s total pain (i.e. social work, chaplain, recreation therapist, physical therapist, pharmacist), thus helping to limit the use of prescription medications for nonphysical pain.

Use an interdisciplinary team to assist with suffering to improve management of the patient’s total pain (i.e. social work, chaplain, recreation therapist, physical therapist, pharmacist), thus helping to limit the use of prescription medications for nonphysical pain.

No maximal therapeutic dose for analgesia has been established. Immediate-release opioids (mu receptor agonists) are short-acting and may be appropriate for acute incidental pain, breakthrough pain, or to initiate and titrate opioid therapy. Long-acting opioids are used around the clock for baseline pain and to maintain analgesia.

No maximal therapeutic dose for analgesia has been established. Immediate-release opioids (mu receptor agonists) are short-acting and may be appropriate for acute incidental pain, breakthrough pain, or to initiate and titrate opioid therapy. Long-acting opioids are used around the clock for baseline pain and to maintain analgesia.

Titration of opioids: Start at lower doses and titrate as tolerance to side effects develops. If pain persists, titration upward by dose increments of 30% to 50% may be necessary to achieve adequate analgesia. For severe uncontrolled pain (extremis), increase the dose by up to 100% and reassess at peak effect. Also adjust based on kidney function when titrating opioids, and stop escalation at adequate pain control or dose limiting side effects (Table 40.1).

Titration of opioids: Start at lower doses and titrate as tolerance to side effects develops. If pain persists, titration upward by dose increments of 30% to 50% may be necessary to achieve adequate analgesia. For severe uncontrolled pain (extremis), increase the dose by up to 100% and reassess at peak effect. Also adjust based on kidney function when titrating opioids, and stop escalation at adequate pain control or dose limiting side effects (Table 40.1).

Common adverse effects of opioids include constipation, sedation, nausea/vomiting, pruritus, sweating, dry mouth, and weakness.

Common adverse effects of opioids include constipation, sedation, nausea/vomiting, pruritus, sweating, dry mouth, and weakness.

With the exception of constipation, tolerance often develops rapidly to most of the common opioid-related adverse effects. Start bowel regimen when initiating opioids unless contraindicated.

With the exception of constipation, tolerance often develops rapidly to most of the common opioid-related adverse effects. Start bowel regimen when initiating opioids unless contraindicated.

Uncommon adverse effects of opioids include dyspnea, urinary retention, confusion, hallucinations, nightmares, myoclonus, dizziness, dysphoria, and hypersensitivity/anaphylaxis.

Uncommon adverse effects of opioids include dyspnea, urinary retention, confusion, hallucinations, nightmares, myoclonus, dizziness, dysphoria, and hypersensitivity/anaphylaxis.

TABLE 40.1Opioid Doses Equianalgesic to Morphine 10 mg Parenteral (IV/IM) for Treatment of Chronic Pain in Cancer Patients (Derby, Chin, Portenoy, 1998)1

Drug | mg Oral | mg IV/IM | Duration (h) | Considerations |

Morphine | 30 | 10 | 2–4 (IV) 2–4 (IR) 8–24 (SR/CR) |

|

Oxycodone | 20 |

| 3–4 (IR) 8–12 (SR) |

|

Hydromorphone | 7.5 | 1.5 | 2–4(IV) 2–4 (IR) |

|

Methadone | — | — | — |

|

Oxymorphone | 10 | 2–4 | ||

Fentanyl |

| 0.1 (100 mcg) | 30–60 min |

|

Fentanyl Transdermal |

|

| 48–72 |

|

IR(Immediate release) SR (Sustained Released) CR (Controlled Release)

1Adapted from Derby S, Chin J, Portenoy RK. Systemic opioid therapy for chronic cancer pain: practical guidelines for converting drugs and routes of administration. CNS Drugs. 1998;9(2):99–109

SAFE AND RESPONSIBLE PRESCRIBING

Physicians have an ethical and regulatory duty to inform the patient of the risks and benefits of long-term opioid use, particularly when initiating treatment in patients at high risk for misuse of opioids (utilize random urine drug tests, referrals to pain management physicians and pain contracts in high-risk patients).

Physicians have an ethical and regulatory duty to inform the patient of the risks and benefits of long-term opioid use, particularly when initiating treatment in patients at high risk for misuse of opioids (utilize random urine drug tests, referrals to pain management physicians and pain contracts in high-risk patients).

Opioid therapy should be tailored to each patient, based on the type and expected duration of pain, as it is difficult to predict which patients will achieve adequate analgesia or develop intolerable adverse effects from a given opioid.

Opioid therapy should be tailored to each patient, based on the type and expected duration of pain, as it is difficult to predict which patients will achieve adequate analgesia or develop intolerable adverse effects from a given opioid.

Certain factors, such as personal or family history of substance abuse, risk of diversion of opioids, or lack of compliance, dictate a multidisciplinary approach, including the involvement of a pain specialist.

Certain factors, such as personal or family history of substance abuse, risk of diversion of opioids, or lack of compliance, dictate a multidisciplinary approach, including the involvement of a pain specialist.

Long-term use of opioids should always be supported by maximal use of co-analgesics and adjuvants, psychological therapy, spiritual counseling, and appropriate follow-up.

Long-term use of opioids should always be supported by maximal use of co-analgesics and adjuvants, psychological therapy, spiritual counseling, and appropriate follow-up.

The CDC has published guidelines for the management of chronic pain to help minimize the harms associated with opioids including overdose and opioid use disorders. These guidelines are useful to help focus on effective treatments available for chronic pain such as adjuvants and non-pharmacological approaches to pain control.

The CDC has published guidelines for the management of chronic pain to help minimize the harms associated with opioids including overdose and opioid use disorders. These guidelines are useful to help focus on effective treatments available for chronic pain such as adjuvants and non-pharmacological approaches to pain control.

Key recommendations include the following:

Key recommendations include the following:

•Nonopioid therapy is preferred for chronic pain outside of active cancer, palliative, and end-of-life care.

•When opioids are used, the lowest possible effective dosage should be prescribed to reduce risks of opioid use disorder and overdose.

•Providers should always exercise caution when prescribing opioids and monitor all patients closely.

Risks of Long-Term Opioid Use

Addiction: Extremely rare in cancer patients but all patients should be assessed for risk factors and continuously reassessed.

Addiction: Extremely rare in cancer patients but all patients should be assessed for risk factors and continuously reassessed.

•Risk Factors: Personal and family history of substance abuse; age; history of preadolescent sexual abuse; certain psychiatric disorders: Attention deficit disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar, schizophrenia, and depression (Webster & Webster, 2005).

Physical dependence: Manifested by withdrawal syndrome at cessation or dose reduction.

Physical dependence: Manifested by withdrawal syndrome at cessation or dose reduction.

Tolerance: Diminution of one or more of the opioid’s effects over time often related to disease progression in the oncology patient.

Tolerance: Diminution of one or more of the opioid’s effects over time often related to disease progression in the oncology patient.

Pseudoaddiction: Iatrogenic syndrome that develops in response to inadequate pain management.

Pseudoaddiction: Iatrogenic syndrome that develops in response to inadequate pain management.

Termination of Opioid Therapy

When opioids are no longer required for pain management, appropriate tapering is essential to reduce the risk of withdrawal syndromes from physical dependence. The recommended regimen involves reducing dosage by 10% to 20% daily, or more slowly if symptoms such as anxiety, tachycardia, sweating, or other autonomic symptoms arise.

When opioids are no longer required for pain management, appropriate tapering is essential to reduce the risk of withdrawal syndromes from physical dependence. The recommended regimen involves reducing dosage by 10% to 20% daily, or more slowly if symptoms such as anxiety, tachycardia, sweating, or other autonomic symptoms arise.

Symptoms may be relieved by clonidine 0.1 to 0.2 mg per day PO up to tid or low-dose transdermal patch every third day.

Symptoms may be relieved by clonidine 0.1 to 0.2 mg per day PO up to tid or low-dose transdermal patch every third day.

Suggested Readings

1.Berger A, Shuster J, Von Roenn H. Principles and practice of palliative care & supportive oncology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013.

2.Cherny N. The management of cancer pain. Cancer J Clin. 2000;50:70–116.

3.Cohen MZ, Easley MK, Ellis C, et al. Cancer pain management and the JCAHO’s pain standards: an institutional challenge. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:519–527.

4.Dalal S, Bruera E. Assessing cancer pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16(4):314–324.

5.Dowwell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(No.RR-1):1–49. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1

6.Hearn J, Higginson IJ. Cancer pain epidemiology: a systematic review. In: Bruera ED, Portenoy RK, eds. Cancer Pain, Assessment and Management. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

7.Jennings AL, Davies A, Higgins JP, Broadley K. Opioids for the palliation of breathlessness in terminal illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4:CDE002066.

8.Koller A, Miaskowski C, De Geest S, Opitz O, Spichiger E. A systematic evaluation of content, structure, and efficacy of interventions to improve patients’ self-management of cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44(2):264–284.

9.Paley CA, Johnson MI, Tashani OA, Bagnall AM. Acupuncture for cancer pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;19(1):CD007753. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007753.pub2.

10.Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, Casey Jr. D, Cross Jr. T, Owens D. Evidence-based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(2):141–146.

11.Quill T, Bower K, Holloway R, et al. Primer of palliative care. 6th ed. Glenview, IL: American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 2014.

12.Temel J, Greer J, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742.

13.von Gunten CF. Evolution and effectiveness of palliative care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(4):291–297.

14.Webster L, Webster R. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the opioid risk tool. Pain Med. 2005;6(6):432–442.

15.Zeppetella G. Opioids for the management of breakthrough cancer pain in adults: a systematic review undertaken as part of an EPCRC opioid guidelines project. Palliat Med. 2011;25(5):516–524.