Procedures in Medical Oncology 42

Kerry Ryan and George Carter

Procedures performed in oncology patients may serve both diagnosis and treatment. This chapter describes common procedures performed in medical oncology, along with special considerations and techniques to assist in performing them rapidly and confidently, and to keep the patient comfortable and well informed.

INFORMED CONSENT AND UNIVERSAL PROTOCOL

Written informed consent, or a legally sufficient substitute, must be obtained before every procedure described here and filed in the patient’s medical record. If appropriate for the planned procedure, mark the procedure side and perform a “time out” to verify correct patient, correct site, and correct procedure.

ANESTHESIA

All procedures are typically performed under local anesthesia. For certain patients and procedures, premedication with a narcotic (fentanyl) and a benzodiazepine (midazolam) should be considered. Lidocaine (1% mixed in a 3:1 or 5:1 ratio with NaHCO3 to prevent the usual lidocaine sting) or alternative anesthetic will ensure proper anesthetic effect.

INSTRUMENTS

Most medical facilities are equipped with sterile trays or self-contained disposable kits specific to each procedure. Additional instruments may be used at the operator’s discretion or preference.

PROCEDURES

Bone Marrow Aspiration and Biopsy

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Analysis of abnormal blood cell production

Analysis of abnormal blood cell production

Staging of hematologic and non-hematologic malignancies

Staging of hematologic and non-hematologic malignancies

Only absolute contraindication is the presence of hemophilia, severe disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, or other severe bleeding disorder.

Only absolute contraindication is the presence of hemophilia, severe disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, or other severe bleeding disorder.

Severe thrombocytopenia is not a contraindication. However, depending on the circumstances may transfuse for platelets <20,000.

Severe thrombocytopenia is not a contraindication. However, depending on the circumstances may transfuse for platelets <20,000.

Skin infection at proposed site of biopsy; consider alternative site.

Skin infection at proposed site of biopsy; consider alternative site.

Biopsy at previously radiated site may cause fibrosis; consider alternative site.

Biopsy at previously radiated site may cause fibrosis; consider alternative site.

Avoid sternal aspirate in patients under the age of 12, with thoracic aortic aneurysm, or with lytic bone disease of ribs or sternum.

Avoid sternal aspirate in patients under the age of 12, with thoracic aortic aneurysm, or with lytic bone disease of ribs or sternum.

Determine if the patient is taking an anticoagulation agent or clopidogrel. If the patient is on these medications, consider stopping them if the risk of bleeding outweighs the risk of thrombosis in the patient. Bone Marrow Biopsy is considered a low risk bleeding for bleeding.

Determine if the patient is taking an anticoagulation agent or clopidogrel. If the patient is on these medications, consider stopping them if the risk of bleeding outweighs the risk of thrombosis in the patient. Bone Marrow Biopsy is considered a low risk bleeding for bleeding.

Sternal aspiration (not recommended as a site of biopsy due to risk of fatal hemorrhage, if it is a chosen site then a skilled and experienced clinician should perform procedure).

Sternal aspiration (not recommended as a site of biopsy due to risk of fatal hemorrhage, if it is a chosen site then a skilled and experienced clinician should perform procedure).

•Patient is supine; head is not elevated.

•Landmarks: sternal angle of Louis and lateral borders of sternum in second intercostal space.

Posterior superior iliac spine aspiration and biopsy (Fig. 42.1) (this is the preferred site of biopsy and aspiration).

Posterior superior iliac spine aspiration and biopsy (Fig. 42.1) (this is the preferred site of biopsy and aspiration).

•Patient is prone or in lateral decubitus position.

Anterior iliac crest aspiration and biopsy (consider for patients with history of radiation to pelvis or extremely obese patients).

Anterior iliac crest aspiration and biopsy (consider for patients with history of radiation to pelvis or extremely obese patients).

•Patient is supine.

FIGURE 42.1Biopsy site in the posterior superior iliac spine. The needle should be directed toward the anterior superior iliac spine.

Some institutions have started performing bone marrow biopsy and aspiration of the posterior iliac crest with the use of CT guidance. Imaging guidance should be considered, particularly, in obese patients where surface anatomical landmarks may prove unreliable.

Posterior superior iliac spine aspiration and biopsy

Posterior superior iliac spine aspiration and biopsy

1.The technique described here is for the Jamshidi bone marrow needle. Other available needles, such as the HS Trapsystem Set, Goldenberg Snarecoil, T-Lok bone marrow biopsy system, are variations of the Jamshidi with their own specific instructions. Also available is the OnControl Bone Marrow Biopsy System that utilizes a battery-powered drill to insert the needle into the iliac bone.

2.The patient may be prone, but the lateral decubitus position is more comfortable for the patient and better for identifying anatomic sites. These positions are suitable for all but the most obese patients. For extremely obese patients or for those who have had radiation to the pelvis, aspirate and biopsy may be taken from the anterior iliac crest.

3.Once the site has been prepared and anesthetized, make a small incision at the site of insertion, and advance the needle into the bone cortex until it is fixed. Attempt to aspirate 0.2 to 0.5 mL of marrow contents. If unsuccessful, advance the needle slightly and try again. Failure to obtain aspirate, known as a “dry tap,” is often due to alterations within the marrow associated with myeloproliferative or leukemic disorders and less commonly due to faulty technique. In such case, a touch preparation of the biopsy often provides sufficient cellular material for diagnostic evaluation.

4.Biopsy can be performed directly after aspiration without repositioning to a different site on the posterior iliac crest. Advance the needle using a twisting motion, without the obturator in place, to obtain the recommended 1.5 to 2 cm biopsy specimen. To ensure successful specimen collection, rotate the needle briskly in one direction and then the other, then gently rock the needle in four directions by exerting pressure perpendicular to the shaft with the needle capped. Gently remove the needle while rotating it in a corkscrew manner. Remove the specimen from the needle by pushing it up through the hub with a stylet, taking care to avoid needle stick injuries. Jamshidi needle kits include a small, clear plastic guide to facilitate this process.

Place a pressure dressing over the site and apply direct external pressure for 5 to 10 minutes to avoid prolonged bleeding and hematoma formation.

Place a pressure dressing over the site and apply direct external pressure for 5 to 10 minutes to avoid prolonged bleeding and hematoma formation.

The pressure dressing should remain in place for 24 hours.

The pressure dressing should remain in place for 24 hours.

The patient may shower after the pressure dressing is removed, but should avoid immersion in water for 1 week after the procedure to avoid infection.

The patient may shower after the pressure dressing is removed, but should avoid immersion in water for 1 week after the procedure to avoid infection.

Infection and hematoma are the most common complications of bone marrow biopsy and aspiration. Careful technique during and after the procedure can minimize these effects.

Lumbar Puncture

Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), including pressure measurement, for diagnosis and to assess adequacy of treatment

Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), including pressure measurement, for diagnosis and to assess adequacy of treatment

Administration of intrathecal chemotherapy

Administration of intrathecal chemotherapy

Increased intracranial pressure

Increased intracranial pressure

Coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia. There is not significant data regarding the optimum platelet count at which a lumbar puncture can be performed. American National Red Cross transfusion guidelines suggested a minimum of 40,000

Coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia. There is not significant data regarding the optimum platelet count at which a lumbar puncture can be performed. American National Red Cross transfusion guidelines suggested a minimum of 40,000

Infection near planned site of lumbar puncture (LP)

Infection near planned site of lumbar puncture (LP)

Anticoagulation agents and clopidogrel should be discontinued before procedure and may be resumed after hemostasis is achieved.

Anticoagulation agents and clopidogrel should be discontinued before procedure and may be resumed after hemostasis is achieved.

Avoid interspaces above L3 (Fig. 42.2), as the conus medullaris rarely ends below L3 (L1–L2 in adults, L2–L3 in children).

Avoid interspaces above L3 (Fig. 42.2), as the conus medullaris rarely ends below L3 (L1–L2 in adults, L2–L3 in children).

The L4 spinous process or L4 to L5 interspace lies in the center of the supracristal plane (a line drawn between the posterior and superior iliac crests).

The L4 spinous process or L4 to L5 interspace lies in the center of the supracristal plane (a line drawn between the posterior and superior iliac crests).

There are eight layers from the skin to the subarachnoid space: skin, supraspinous ligament, interspinous ligament, ligamentum flava, epidural space, dura, subarachnoid membrane, and subarachnoid space.

There are eight layers from the skin to the subarachnoid space: skin, supraspinous ligament, interspinous ligament, ligamentum flava, epidural space, dura, subarachnoid membrane, and subarachnoid space.

FIGURE 42.2Anatomy of the lumbar spine. Ideal needle insertion is between L3 and L4 interspace, which can be found where the line joining the superior iliac crests intersects the spinous process of L4. Positioning of patient for lumbar puncture: in lateral decubitis or sitting positon. (From Zuber TJ, Mayeaux EF. Atlas of Primary Care Procedures. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1994:13.)

The fluoroscopic guidance for a LP should be considered if multiple attempts without imaging were performed and were unsuccessful. Also, could be considered if the patient is obese or has a difficult anatomy due to prior surgery.

1.Describe the procedure to the patient, with assurances that you will explain what you are about to do before you do it.

2.Patient should be in a lateral decubitus or sitting position. The prone position is usually used for LPs performed under fluoroscopic guidance and will not be discussed here. The lateral decubitus position is preferable for obtaining opening pressures. The seated position may be used if the patient is obese or has difficulty remaining in the lateral decubitus position. Either seated or lying on one side, the patient should curl into a fetal position with the spine flexed to widen the gap between spinous processes (Fig. 42.2).

3.Identify anatomic landmarks and the interspace to be used for the procedure.

4.Using sterile technique, prepare the area and one interspace above or below it with povidone-iodine solution. Drape the patient, establishing a sterile field.

5.Using 1% lidocaine/bicarb mixture, anesthetize the skin and deeper tissues, carefully avoiding epidural or spinal anesthesia.

6.Insert the spinal needle through the skin into the spinous ligament, keeping the needle parallel to the bed or table. Immediately angle the needle 30 to 45 degrees cephalad. The bevel of the spinal needle should be positioned facing the patient’s flank, allowing the needle to spread rather than cut the dural sac. Advance the needle through the eight layers in small increments. With practice, an experienced operator can identify the “pop” as the needle penetrates the dura into the subarachnoid space. Even so, it is wise to remove the stylet to check for CSF before each advance of the needle.

7.When the presence of CSF is confirmed, attach a manometer (either traditional manometer or digital pressure transducer device) to the hub of the needle to measure opening pressure. Collect the minimum amount of CSF required to perform the tests being ordered, typically 8 to 15 mL of CSF is required. If special studies are required, up to 40 mL of CSF may be safely removed. Confirm with your laboratory the order of the tests that should be done on each tube, as different laboratories have different preferences.

8.Replace the stylet, withdraw the needle, observe the site for CSF leak or hemorrhage, and bandage appropriately.

9.Ease the patient into a recumbent position. Bedrest is often still done for a period of time following a LP; however, it has been established that bed rest does not decrease the incidence of headache after lumbar puncture.

Spinal headache occurs in approximately 20% of patients after LP. Incidence appears to be related to needle size and CSF leak and not to post-procedure positioning. There is no evidence that increased fluid intake prevents spinal headache. It is characterized by pounding pain in the occipital region when the patient is upright. Incidence is highest in female patients, younger patients (peak 20 to 40), and patients with a history of headache prior to LP. Patients should remain recumbent if possible and take over-the-counter analgesics. For severe and/or persistent spinal headache, stronger medication, caffeine, or an epidural blood patch may be indicated. Data indicate that a Sprotte (“pencil-tipped”) needle reduces the risk of post-LP headache.

Spinal headache occurs in approximately 20% of patients after LP. Incidence appears to be related to needle size and CSF leak and not to post-procedure positioning. There is no evidence that increased fluid intake prevents spinal headache. It is characterized by pounding pain in the occipital region when the patient is upright. Incidence is highest in female patients, younger patients (peak 20 to 40), and patients with a history of headache prior to LP. Patients should remain recumbent if possible and take over-the-counter analgesics. For severe and/or persistent spinal headache, stronger medication, caffeine, or an epidural blood patch may be indicated. Data indicate that a Sprotte (“pencil-tipped”) needle reduces the risk of post-LP headache.

Nerve root trauma is possible but rare. A low interspace entry site reduces the risk of this complication.

Nerve root trauma is possible but rare. A low interspace entry site reduces the risk of this complication.

Cerebellar or medullar herniation occurs rarely in patients with increased intracranial pressure. If recognized early, this process can be reversed.

Cerebellar or medullar herniation occurs rarely in patients with increased intracranial pressure. If recognized early, this process can be reversed.

Infection, including meningitis.

Infection, including meningitis.

Bleeding. A small number of red blood cells in the CSF is common. In approximately 1% to 2% of patients, serious bleeding can result in neurologic compromise from spinal hematoma. Risk is highest in patients with thrombocytopenia or serious bleeding disorders, or patients given anticoagulants immediately before or after LP.

Bleeding. A small number of red blood cells in the CSF is common. In approximately 1% to 2% of patients, serious bleeding can result in neurologic compromise from spinal hematoma. Risk is highest in patients with thrombocytopenia or serious bleeding disorders, or patients given anticoagulants immediately before or after LP.

Paracentesis

To confirm diagnosis or assess diagnostic markers

To confirm diagnosis or assess diagnostic markers

As treatment for ascites resulting from tumor metastasis or obstruction

As treatment for ascites resulting from tumor metastasis or obstruction

The complication rate for this procedure is about 1%.

The complication rate for this procedure is about 1%.

The potential benefit of therapeutic paracentesis outweighs the risk of coagulopathy. However, they should be avoided in patients with disseminated intravascular coagulation.

The potential benefit of therapeutic paracentesis outweighs the risk of coagulopathy. However, they should be avoided in patients with disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Perform with caution in patients that have organomegaly, bowel obstruction, distended bladder, or intra-abdominal adhesions. Consider ultrasound guidance in these patients. Also, a nasogastric tube should be placed first in patients with bowel obstruction and a urinary catheter should be inserted in patients with urinary retention.

Perform with caution in patients that have organomegaly, bowel obstruction, distended bladder, or intra-abdominal adhesions. Consider ultrasound guidance in these patients. Also, a nasogastric tube should be placed first in patients with bowel obstruction and a urinary catheter should be inserted in patients with urinary retention.

Modify site location to avoid surgical scars. Surgical scars have been associated with tethering of the bowel to the abdominal wall.

Modify site location to avoid surgical scars. Surgical scars have been associated with tethering of the bowel to the abdominal wall.

Identify the area of greatest abdominal dullness by percussion, or mark the area of ascites via ultrasound. Take care to avoid abdominal vasculature and viscera.

Identify the area of greatest abdominal dullness by percussion, or mark the area of ascites via ultrasound. Take care to avoid abdominal vasculature and viscera.

1.Place the patient in a comfortable supine position at the edge of a bed or table.

2.Identify the area of the abdomen to be accessed (Fig. 42.3). Ultrasound can be used to confirm the presence of fluid and the absence of bowel or spleen in the selected site.

3.Prepare the area with povidone-iodine solution and establish a sterile field by draping the patient.

4.Anesthetize the area with a 1% lidocaine/bicarb mixture.

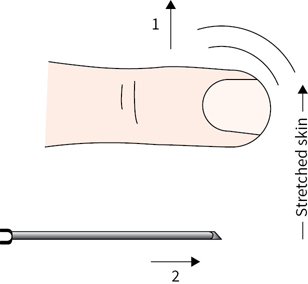

5.For diagnostic paracentesis, insert a 22- to 25-gauge needle attached to a sterile syringe into the skin, then pull the skin laterally and advance the needle into the abdomen. Release the tension on the skin and withdraw an appropriate amount of fluid for testing. This skin-retraction method creates a “z” track into the peritoneal cavity, which minimizes the risk of ascitic leak after the procedure (Fig. 42.4).

6.For therapeutic paracentesis, use the z-track method with a multiple-port flexible catheter over a guide needle. When the catheter is in place, the ascites may be evacuated into multiple containers. Make sure that the patient remains hemodynamically stable while removing large amounts of ascites.

7.When the procedure is completed, withdraw the needle or catheter and, if there is no bleeding or ascitic leakage, place a pressure bandage over the site.

8.Following therapeutic paracentesis, the patient should remain supine until all vital signs are stable. Offer the patient assistance getting down from the bed or table.

9.If necessary, standard medical procedures should be used to reverse orthostasis. The patient should be hemodynamically stable before being allowed to leave the operating area.

FIGURE 42.3Sites for diagnostic paracentesis. (From Zuber TJ, Mayeaux EF. Atlas of Primary Care Procedures. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1994:46.)

FIGURE 42.4“Z”-track technique for inserting needle into peritoneal cavity. (From Zuber TJ, Mayeaux EF. Atlas of Primary Care Procedures. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1994:47.)

Hemorrhage, ascitic leak, infection, and perforated abdominal viscus have been reported. Properly siting paracentesis virtually eliminates these complications.

Hemorrhage, ascitic leak, infection, and perforated abdominal viscus have been reported. Properly siting paracentesis virtually eliminates these complications.

Thoracentesis

Diagnostic or therapeutic removal of pleural fluid.

Diagnostic or therapeutic removal of pleural fluid.

There are no absolute contraindications to diagnostic thoracentesis. Relative contraindications include the following:

Coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia (platelets less than 50,000/uL). A decision to reverse the coagulopathy or correct the thrombocytopenia needs to be individualized, weighing the risks and benefits, as a thoracentesis is considered a low-risk bleeding procedure.

Coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia (platelets less than 50,000/uL). A decision to reverse the coagulopathy or correct the thrombocytopenia needs to be individualized, weighing the risks and benefits, as a thoracentesis is considered a low-risk bleeding procedure.

Bullous emphysema (increased risk of pneumothorax)

Bullous emphysema (increased risk of pneumothorax)

Pleural effusion less than 1 cm at its maximum depth adjacent to the parietal pleura (when ultrasound guidance is used).

Pleural effusion less than 1 cm at its maximum depth adjacent to the parietal pleura (when ultrasound guidance is used).

Patients on mechanical ventilation with positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) have no greater risk of developing a pneumothorax than non-ventilated patients. However, mechanically ventilated patients are at greater risk of developing tension physiology or persistent air leak if a pneumothorax does occur.

Patients on mechanical ventilation with positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) have no greater risk of developing a pneumothorax than non-ventilated patients. However, mechanically ventilated patients are at greater risk of developing tension physiology or persistent air leak if a pneumothorax does occur.

Patients unable to cooperate.

Patients unable to cooperate.

Cellulitis, if thoracentesis would require penetrating the inflamed tissue.

Cellulitis, if thoracentesis would require penetrating the inflamed tissue.

Ultrasound-guided thoracentesis has become a standard of practice in most institutions for performing a thoracentesis, as it decreases the risk of pneumothorax and has a higher sensitivity for identifying pleural effusions. An ultrasound should be used to identify the puncture site either while the procedure is being done or before the procedure is done to mark the site. If a pleural effusion is complex or loculated, CT imaging may be required.

Place the patient in a seated position facing a table, arms resting on a raised pillow. Have the patient lean forward 10 to 15 degrees to create intercostal spaces. The lateral recumbent position (with the side of the pleural effusion up) can be used if the patient is unable to sit up.

Place the patient in a seated position facing a table, arms resting on a raised pillow. Have the patient lean forward 10 to 15 degrees to create intercostal spaces. The lateral recumbent position (with the side of the pleural effusion up) can be used if the patient is unable to sit up.

Perform thoracentesis through the seventh or eighth intercostal space, along the posterior axillary line. With guidance of ultrasound the procedure may be performed below the fifth rib anteriorly, the seventh rib laterally, or the ninth rib posteriorly. Without radiographic guidance, underlying organs may be injured.

Perform thoracentesis through the seventh or eighth intercostal space, along the posterior axillary line. With guidance of ultrasound the procedure may be performed below the fifth rib anteriorly, the seventh rib laterally, or the ninth rib posteriorly. Without radiographic guidance, underlying organs may be injured.

If ultrasound is not available, the extent of pleural effusion is indicated by decreased tactile fremitus and dullness to percussion. Begin percussion at the top of the chest and move downward, listening for a change in sound. When a change is noted, compare to the percussive sound in the same interspace and location on the opposite side. This will denote the upper extent of pleural effusion.

If ultrasound is not available, the extent of pleural effusion is indicated by decreased tactile fremitus and dullness to percussion. Begin percussion at the top of the chest and move downward, listening for a change in sound. When a change is noted, compare to the percussive sound in the same interspace and location on the opposite side. This will denote the upper extent of pleural effusion.

1.After the appropriate site has been identified either by ultrasound or physical exam, position the patient and clean the site with antiseptic. Initially, infiltrate the epidermis using a 25-gauge needle and 1% or 2% lidocaine. Next, with a syringe attached to a 22-guage-needle advance toward the rib and then “walk” over the superior edge of the rib (Fig. 42.5). This decreases the risk of injury to the neurovascular bundle. Aspirate frequently to ensure that no vessel has been pierced and to determine the distance from the skin to the pleural fluid. When pleural fluid is aspirated, remove the anesthesia needle and note the depth of penetration.

2.A small incision may be needed to pass a larger gauge thoracentesis needle into the pleural space. Generally, a 16- to 19-gauge needle with intracath is inserted just far enough to obtain pleural fluid. Fluid that is bloody or different in appearance from the fluid obtained with the anesthesia needle may be an indication of vessel injury. In this case, the procedure must be stopped. If there is no apparent change in the pleural fluid aspirated, advance the flexible intracath and withdraw the needle to avoid puncturing the lung as the fluid is drained. Using a flexible intracath with a three-way stopcock allows for removal of a large volume of fluid with less risk of pneumothorax. If only a small sample of pleural fluid is needed, a 22-gauge needle connected to an airtight three-way stopcock is sufficient. Attach tubing to the three-way stopcock and drain fluid manually or by vacutainer. Withdrawing more than 1,000 mL per procedure requires careful monitoring of the patient’s hemodynamic status. As the needle is withdrawn, have the patient hum or do the Valsalva maneuver to increase intrathoracic pressure and lower the risk of pneumothorax.

3.After the procedure, obtain a chest radiograph to determine the amount of remaining fluid, to assess lung parenchyma, and to check for pneumothorax. Small pneumothoraces do not require treatment; pneumothoraces involving >50% lung collapse do.

FIGURE 42.5Thoracentesis. (a) “Z”-track technique for anesthetizing to prevent injury to neurovascular bundle. (b) Advancement of soft plastic catheter through the needle into pleural space. (Zuber TJ, Mayeaux EF. Atlas of Primary Care Procedures. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1994:26, 27.)

Pneumothorax

Pneumothorax

Air embolism (rare)

Air embolism (rare)

Infection

Infection

Pain at puncture site

Pain at puncture site

Bleeding

Bleeding

Splenic or liver puncture

Splenic or liver puncture

Suggested Readings

1.Avery RA, Mistry RD, Shah SS, et al. Patient position during lumbar puncture has no meaningful effect on cerebrospinal opening pressure on children. J Child Neurol. 2010 Feb 22 [Medicine].

2.Desalpine M, Bragga PK, Gupta PK, Kataria AS. To evaluate the role of bone marrow aspiration and bone marrow biopsy in pancytopenia. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014 Nov;8(11):FC 11-5[Medicine]. [Full Text].

3.Duncan DR, Morgenthaler TI, Ryu JH, Daniels CE. Reducing iatrogenic risk in thoracentesis: establishing best practice via experimental training in a new-risk environment. Chest. 2009 May;135(5):1315–1320 [Medicine].

4.Ellenby MS, Tegtmeyer K, Lai S, Braner DA. Videos in clinical medicine. Lumbar puncture. N Engl J Med. 2006:355(13):e12.

5.Evans RW, Armon C, Frohman EM, Goodin DS. Assessment: prevention of post-lumbar puncture headaches: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55(7):909–914.

6.Fend F, Tzankov A, Bink K, et al. Modern techniques for the diagnostic evaluation of trepine bone marrow biopsy: methodological aspects and application. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 2008;42(4):203–252.[Medicine].

7.Hooper C, Maskel N, BTS audit team. British Thoracic Society national pleural procedures audit 2010. Thorax. 2011: 66(7):636–637.

8.Humphries JE. Dry tap bone marrow aspiration: clinical significance. Am J Hematol. 1990;35(4):247–250.

9.Kuntz KM, Kokmen E, Stevens JC, Miller P, Offord KP, Ho MM. Post-lumbar puncture headaches: experience in 501 consecutive procedures. Neurology. 1992;42(10):1884–1887.

10.LeMense GP, Sahn SA. Safety and value of thoracentesis in medical ICU patients. J Intensive Care Med. 1998;13:144.

11.Malempati S, Joshi S, Lai S, Braner D, Tegtmeyer K. Bone marrow aspiraiton and biopsy. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:e28.

12.Mc Gibbon A, Chen GI, Peltekian KM, van Zanten SV. An evidence base manual for abdominal paracentesis. Dig Dis Sci. 2007 Dec;52(12):3307–3315.[Medicine].

13.McCartney JP, Adams JW II, Hazard PB. Safety of thoracentesis in mechanically ventilated patients. Chest. 1993;103(6);1920–1921.

14.Quesada AE, Tholpady A, Wanger A, Nguyen AN, Chen L. Utility of bone marrow examination for workup of fever of unknown origin in patients with HIV/AIDS. J Clin Pathol. 2015 Mar;68(3):241–245. [Medicine].

15.Runyon BA. Paracentesis of ascitic fluid. A safe procedure. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146(11):2259–2261.

16.Spyropoulos AC, Douketis JD. How I treat anticoagulated patients undergoing an elective procedure or surgery. Blood 2012;120:2954.

17.Strupp M, Schueler O, Straube A, Von Stuckrad-Barre S, Brandt T. “Atraumatic” Sprotte needle reduces the incidence of post-lumbar puncture headaches. Neurology. 2001;57(12):2310–2312.

18.Swords A, Anguita J, Higgins RA, et al. A new rotary powered device for bone marrow aspiration and biopsy yields superior specimens with less pain: results of a randomized clinical study. Blood 2010;116(21):650–651.

19.Thomsen T, DeLaPena J, Setnik G. Thoracentesis. N Engl J Med. 2006; 255:e16.

20.Thomsen TW, Shaffer RW, White B, Setnik GS. Videos in clinical medicine. Paracentesis. N Engl J Med. 2006 Nov 9;355(19):e21.[Medicine].

21.Tung CE, So YT, Lansberg MG. Cost comparison between the atraumatic and cutting lumbar puncture needles. Neurology. 2012 Jan 10;78(2):109–113. Epub 2011 Dec 28.

22.Van Veen JJ, Nokes TJ, Markis M. The risk of spinal haematoma following neuraxial anaesthesia or lumbar puncture in thrombocytopenia invividuals. Br J Haemetol. 2009;148:15–25.

23.Wickbom A, Cha SO, Ahlisson A. Thoracentesis in cardiac surgery patients. Multimed Man Cardiothoracic Surg. 2015.[Medicine].

24.Williams J, Lyle S, Umpathi T. Diagnostic lumbar puncture minimizing complications. Intern Med J. 2008;38:587–591.

25.Wolff SN, Katzenstein AL, Phillips GL, Herzig GP. Aspiration does not influence interpretation of bone marrow biopsy cellularity. Am J Clin Pathol. 1983;80(1):60–62.

26.Zuber TJ, Mayeaux EF. Atlas of Primary Care Procedures. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wildins, 1994:26, 27.