Chapter 21

TRUE CONFESSIONS

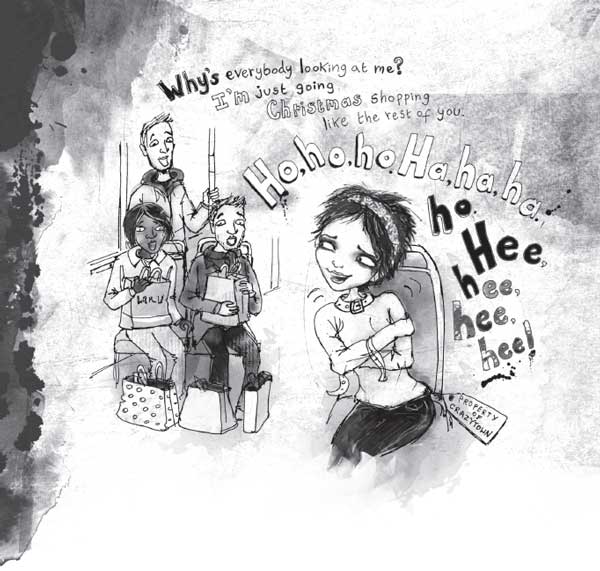

I love taking the bus to Portland. It’s fun to watch people whiz past the windows as I ride along, imagining their lives. There are worse ways to spend a sleety Saturday.

The bus is so toasty that I have to take off my coat, which is fine with me. Mrs. Morris insists that the cold air is good for her circulation, so she keeps our place pretty chilly. The bus is a nice change from my seven-degree bedroom.

It’s already mid-December, and everyone around me is loaded down with red and silver shopping bags. I’m not going shopping, though. I’m actually on my way to see Dr. Marcuse. She’s the one from Crazytown and she is 100 percent awesome with zero byproducts. I’m serious.

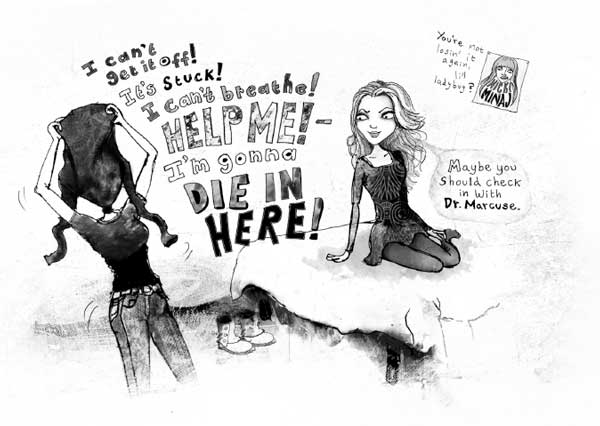

Anyway, don’t worry—nothing dramatic has happened. Well, nothing except this mild freak-out I had the other day when I tried to borrow Brainzilla’s turtleneck.

Once I got the turtleneck off my head and took a few deep breaths, I realized that Katie was right. Not just because of the turtleneck, but also because of how worried I got when I couldn’t find Mrs. Morris the other night. And also because I really like Dr. Marcuse.

Not because I’m having a psychiatric emergency. I swear.

Anyway, I make it to St. Augustine, and I just have to ask, is it weird to say that a mental hospital feels homey?

I actually feel kind of happy to be back here. It’s a bit like visiting my old elementary school: There’s my old locker! There’s my old teacher! There’s that same dead fly that has been on the windowsill for three months!

But it’s also like visiting your old school in that there are all these new faces. I check in at the desk, then walk past the cozy activity room where a bunch of teen girls are using safety scissors to cut up magazines for a collage. Right. It’s Saturday—art therapy. Mr. Noyes is smiling at one of the girls, explaining something in his slow, patient way, gesturing with his tiny, clean hands. He doesn’t notice me as I pause in the doorway, remembering what it was like to be one of those girls at the white table.

I don’t feel any crazier now than I did then.

Laughter bubbles from the activity room as I move toward Dr. Marcuse’s office. Light streams in through the large windows, lighting up the colorful fish mural that lines the hall. A nurse in Tweety Bird scrubs pushes a medication cart out of one of the rooms. Her face lights up with a huge smile.

“Hey, there, Ms. Maggie,” Opal says, waving at me with her fabulous nails. They’re painted with little Tweety Birds. “Guess you missed us too much?”

“I’m just here to check in with Dr. Marcuse,” I say, walking into her soft-bodied hug. She smells like hand cream.

“Well, you’re looking real good, sweetheart. You take care of yourself.” And Opal gives me a little squeeze, like she really is happy to see me, and really is happy I’m better.

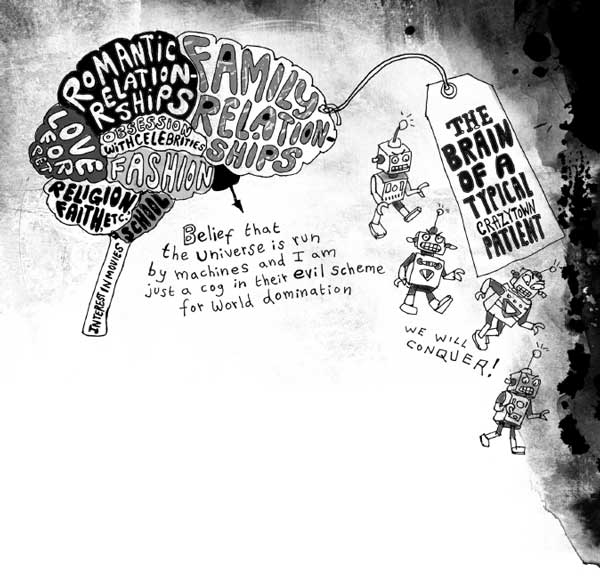

Here is the thing about Crazytown: It’s shockingly normal. It isn’t like the mental hospitals you see in movies, where the staff is all psycho and desperate to give people lobotomies. Even the so-called patients wouldn’t strike you as nutcases. That’s because most of the crazy goes on inside their heads.

At Crazytown, the staff encourages you to, like, live in the real world most of the time. Then, with your doctor, you work on those little parts of your brain that are tripping you up. So most of the day is spent doing art or playing games or exercising or whatever. It’s kind of like camp. Minus the archery.

Dr. Marcuse’s door is half open, like it’s inviting me in, but I give a soft knock anyway.

“Maggie, is that you?” she calls, and when I walk in, she gets up from behind her desk and comes over to grab my hands. Dr. Marcuse isn’t a very huggy person, but I can tell she likes me.

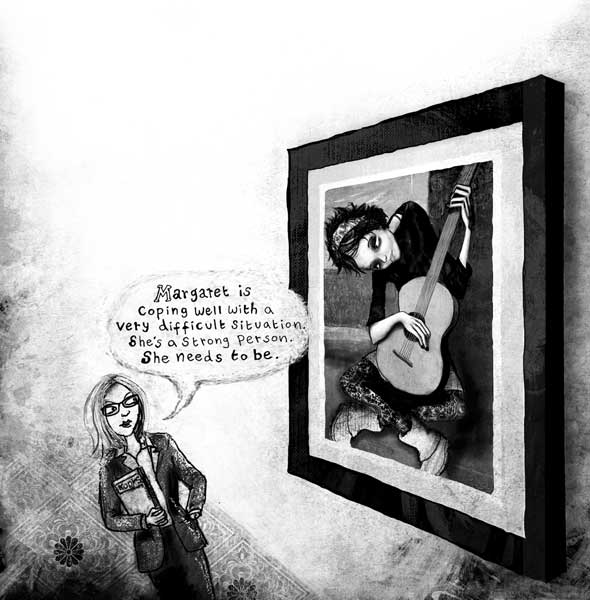

I sit down in the same old comfortable wing chair. When I was at Crazytown, I saw Dr. Marcuse every day, sometimes twice a day. I know every detail of this room: the slightly crooked diploma from Columbia on the wall behind her head, the elegant aloe plant on her dark wood desk, the framed print of a yellow elephant that sits propped among the books on her disordered shelves, the green fabric wall hanging.

Who wouldn’t get better in a place like this, talking to someone like Dr. Marcuse? After ten days, she pronounced me “sound of mind.” I’m totally fine now. Mostly totally fine. Still a little blue sometimes, but hey—it worked for Picasso, right?