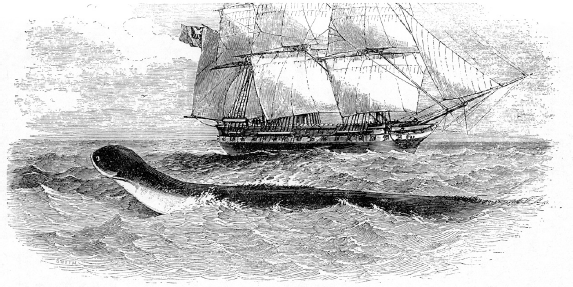

OF ALL THE WORLD’S STOMPING, slithering, and bloodsucking monsters, nothing else quite matches the Great Sea Serpent. Enduring for centuries, the sea serpent legend has a unique place in the history of cryptozoology—and a unique place in my own family history as well.

One of the lessons of cryptozoological investigation is that most cryptids are brand-spanking new. The Loch Ness monster (a Hollywood spin-off) was born after my own grandmother. The modern Bigfoot legend premiered the same year as

Leave It to Beaver. If the chupacabra (goat sucker) were a person, it would be in high school, the story of this vampiric cryptic from Puerto Rico being only as old as the sci-fi horror movie

Species (1995), on which it was based.

1But sea monsters are, if you will forgive me, a different kettle of fish. Descriptions of sea monsters are as old as written language. They appear in the Bible and in the writings of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Even by the very strictest definition, the fully formed modern version of the Great Sea Serpent goes back at least to 1755, when Bishop Erich Pontoppidan’s book The Natural History of Norway made it a permanent part of global popular culture.

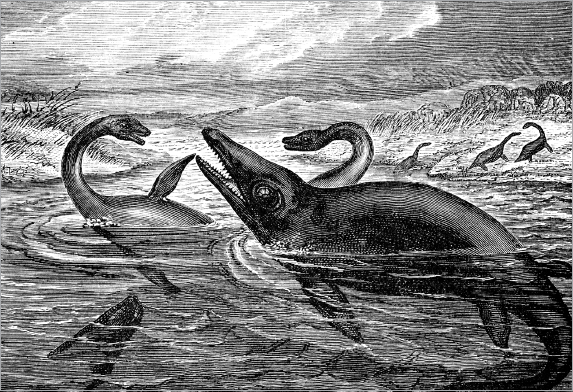

Over the past 250 years, sea serpents have enjoyed a unique level of support from the scientific community. They have been endorsed, discussed, or denounced by some of the great scientific minds in history, including such legendary pioneers of biology as Louis Agassiz, Richard Owen, and Thomas Henry Huxley. Developing alongside the evolution of paleontology and the discovery of dinosaurs and their marine-reptile cousins, the high-level debates about the reality of sea serpents that took place in learned journals and gas-lit parlors helped define the methods and borders of modern science.

2The idea of vast creatures sliding undetected through the abyss stirred my imagination deeply at a young age. How could it not? What kid could read a story like Ray Bradbury’s “The Fog Horn” (about a huge, ancient sea serpent drawn to a lighthouse) and not thrill to the idea that it could be true? Imagine such a primeval monster, as Bradbury did, “hid away in the Deeps. Deep, deep down in the deepest Deeps. Isn’t

that a word now … the Deeps. There’s all the coldness and darkness and deepness in the world in a word like that.”

3Why, anything could be down there, couldn’t it?

But I had a very personal reason to think that sea serpents were just waiting out there to be discovered: my parents saw one, when I was a young child. I was raised as something of a nomad. My family lived in a silver travel trailer and spent winters on the beaches near Victoria, British Columbia. We just pulled in the trailer, and presto: home. On one of those beaches, my parents saw the twentieth century’s best-known regional version of the Great Sea Serpent: Victoria’s own Cadborosaurus. I’ll let my father tell the story as he remembers it—a story that has shaped my career to this day:

We were right by the water. We were young and happy and life was good. We had a morning ritual of sitting up in bed and looking out to sea while we enjoyed our morning cup of tea.

This particular beautiful summer morning we thought that we saw Cadborosaurus. We both saw it at the same time, and both said something stupid like “Wow, look, a sea serpent,” followed by embarrassment at what we had just said. We jumped up in our bathrobes and ran barefoot down to the water’s edge.

There it was, swimming along just 40 feet or so from shore. It was swimming parallel to the beach and making pretty good time. We had to walk briskly to keep up with it, and we wished we had the camera.

We were both saying things like, “It’s definitely a sea serpent, see the head? I can even see its eyes!”

It was about 30 ft. long, dark in color and clear as day. It had a head, a neck, and many humps. It was swimming along in perfectly coordinated undulating motion. It appeared to be very real, alive, efficient … and very clearly a sea serpent.

4What was it, really? Well, that’s the question, isn’t it? My parents had diverging interpretations of this experience, but as a kid, it seemed obvious to me: it was a sea monster! And I was going to catch it.

For years, I dreamed of just that. I scoured catalogues for monster-hunting equipment. I designed logos for my future Cadborosaurus expeditions. I got my local librarian to help me write to the Loch Ness Phenomena Investigation Bureau. And today, bizarrely enough, I find myself in the professional position of actually investigating monsters (albeit skeptically). Through it all, it seemed—and still seems—perfectly plausible that a sea serpent–like animal could exist. Why not? The ocean is certainly big enough, and it is an exhilarating fact that many of its inhabitants remain completely unknown.

Could some sea serpent stories be true? As with other cryptid mysteries, the best place to start is at the beginning. How did the idea get started in the first place? How did it take the form that it did? Why, for example (and this deeply puzzled me as a kid), are classic sea serpents so often described with horse-like manes?

Why, of all things, would sea serpents have heads that resemble those of horses (or cows, sheep, or camels)?

SEA MONSTERS IN ANTIQUITY

Sea Serpents in Ancient Literature and Classical Art

To find the roots of the sea serpent legend, we’ll look back almost 3,000 years to the sunny shores of the Mediterranean. If sea serpents are real, it is likely that the sophisticated coastal cultures of the ancient world would have described and depicted them. After all, the ancients were no slouches, and trade goods and information flowed throughout Eurasia for thousands of years. Besides, sea serpents would tend to stick out. My parents’ 30-foot Cadborosaurus was a minnow by sea serpent standards. Other witnesses have described sea serpents as long as a blue whale or larger: various reports have put them at 150, 200, 300, or even a staggering 600 feet long. A 600-foot sea serpent would be not so much a cryptid as Godzilla.

5 Surely, ancient sources would mention the largest animal ever to exist?

Sea monsters are as old as literature—and for good reason! Imagine the ocean through the eyes of the ancients: endless, dark, and deadly. When brave warriors, traders, and fishermen ventured out over that alien abyss, they could only imagine what vast and terrible dangers stirred below. One thing they did know: sometimes the sea swallowed men. To ancient mariners, explains classical scholar Emily Vermeule, the sea was “more like a tightrope over an open tiger-pit than a safe road home.”

6Accordingly, the seas of the ancient imagination swarmed with a teeming variety of powerful, malevolent monsters. Many were inspired by true-life animals filtered through folklore, mythology, and the tales of travelers returned from distant lands. Even as these real and folkloric creatures were named, they also blended easily into one another. In particular, the dividing lines between sea monsters, whales, dragons, and snakes were fluid. Think of the biblical Leviathan: a primordial sea monster, yet simultaneously a dragon, but considered by many to be a whale. The book of Job emphasizes the fiery aspects of this vast (if vague) ocean-dwelling monster:

Out of his mouth go flaming torches; sparks of fire leap forth.

Out of his nostrils comes forth smoke, as from a boiling pot and burning rushes.

His breath kindles coals, and a flame comes forth from his mouth. (41:11–13)

Isaiah amplifies this hybrid description, calling Leviathan “the dragon that is in the sea” (27:1).

7 At the same time, many scholars argue that Job’s version of Leviathan is based on a real animal, with the whale among the leading contenders.

8 (Such a distorted, mythologized view of a real animal would be consistent with the general lack of familiarity with marine life among the relatively land-locked writers of the Hebrew Bible. As archaeologists John K. Papadopoulos and Deborah Ruscillo note, the Hebrew Bible does not record even one species name to identify any particular sort of fish. Even Jonah’s “whale” is identified simply as “big fish.”)

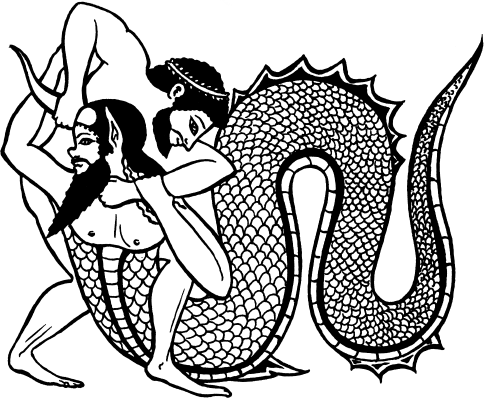

9

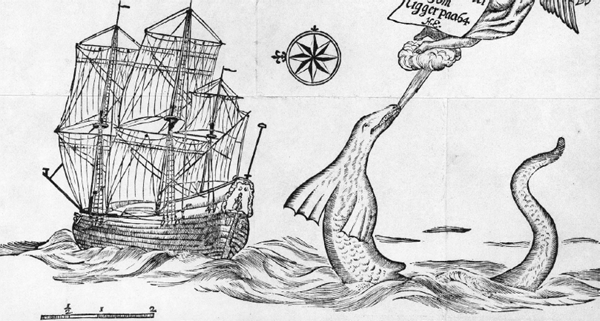

Figure 5.1 A ketos depicted on a Caeretan hydria black-figure vase, ca. 530–520 B.C.E. (Stavros S. Niarchos Collection). John Papadopoulos and Deborah Ruscillo note the “cetacean-like flippers . . . plus what looks suspiciously like a whale fin about two-thirds down the body.” (Redrawn by Daniel Loxton, with reference to John Boardman, “‘Very Like a Whale’: Classical Sea Monsters,” in Monsters and Demons in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds, ed. Anne E. Farkas, Prudence O. Harper, and Evelyn B. Harrison [Mainz: Zabern, 1987], and a photograph by S. Hertig [Zurich University Collection])

By contrast, writers and artists immersed in the coastal culture of the ancient Greeks faithfully described many dangerous, delightful, and delicious sea animals in detail. But whales, being relatively rare in the Mediterranean, were as hard to study as they were terrifying. As a result, no clearly identifiable, naturalistic Greek images of whales are known to exist.

10 Instead, “sea monster” and “whale” were interchangeable concepts in early classical literature, with the same word,

ketos, used for both.

Ketos is the basis for the word “cetacean,” but it was not originally restricted to whales: it was an umbrella term for anything big and scary that lived in the sea, including whales, sharks, and tuna (

figure 5.1).

Alongside the merman (Triton) and the hippocamp (a Capricorn-like creature whose body combines the front half of a horse with the back half of a fish, to which we will return), the

ketos was one of the three standard sea monster types employed by Greek artists. As creative vase painters and sculptors explored the

ketos form over many centuries, several varieties emerged. Many images of the

ketos straightforwardly depict very big fish. Other artists imagined

ketos monsters as grotesque hybrids: fishes with the heads of powerful terrestrial animals. Once this mix-and-match scheme became common, artists could combine creatures as creatively as they wished.

11 By the Hellenistic period (the three or four centuries following the continent-spanning conquests of Alexander the Great), sea monster art had become more light-hearted and fantastic. Artists were happy to try inventive depictions, as archaeologist Katharine Shepard notes: “We find for the first time in the Hellenistic period the sea-centaur, -bull, -boar, -stag, -lion, -panther and -pantheress.”

12Papadopoulos and Ruscillo describe a third style of

ketos illustration, which is much more intriguing from a cryptozoological perspective: “An alternative manner of representing the

ketos is as a large serpent-like creature: a snake by any other name. Like the big fish, a suitably massive snake was one, relatively straightforward, way of giving iconographic substance to a massive sea creature that was, above all else, mysterious and frightening.”

13 This last sort of fantastic, vertically undulating beast included elements from the mutually blurry notions of dragons, fish, whales, and pythons (among other animals),

14 but to the modern eye they scream “sea serpent.” Just look at that vertical undulation! Does this mean that the ancients did have knowledge of a genuine sea serpent 2,000 years before the modern legend emerged in Scandinavia?

Not so fast. It is very easy for modern audiences to be misled when interpreting out-of-context artworks from other times and other cultures. For example, UFOlogists who see “evidence” of flying saucers in medieval or Renaissance paintings mistakenly project their own expectations onto stylized depictions of clouds, the Holy Spirit, or even broad-brimmed hats.

15 As it happens, the long, snaky, vertically undulating tails that make

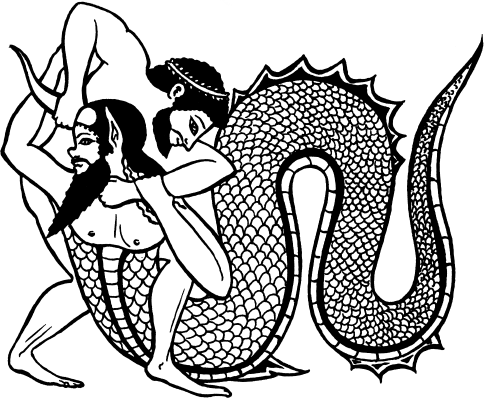

ketos images resemble our notion of sea serpents were not unique to those depictions. The same tails were used just as often for hippocamps and for mermen (

figure 5.2). It is worth noting that while neither fish nor serpents move by means of vertical undulation, a wavy or an arched body is extremely handy for indicating sinuousness in profile images on vases or shallow relief sculptures. “Of course,” notes legendary cryptozoological writer Bernard Heuvelmans (one of the coiners of the word “cryptozoology”),

16 “most primitive or childish pictures show snakes wriggling in the same way, but this is simply because it needs some skill in perspective to draw the side view of an animal that wiggles horizontally.”

17

Figure 5.2 Herakles wrestles the river deity Akheloios on an Attic red-figure vase attributed to Oltos, ca. 520 B.C.E. (Redrawn after London E437, British Museum, London)

Is there reason to think that artists modeled the

ketos on a genuine serpentine animal? No. The

ketos may be widespread in classical art, but it cannot be used as evidence for the existence of a cryptid. As art historian and archaeologist John Boardman explains in an influential overview of the

ketos, it is a wasted effort to speculate about “our beast’s relationship to real or imagined sea monsters since we can show that his creation is an artistic amalgam not much troubled by what swam or was thought to swim in the Mediterranean.”

18 Moreover, it is clear that images of the

ketos changed with the fashions among artists—a pattern more consistent with the depiction of imagined creatures than real animals.

But consider the opposite: What if art inspired the notion of the sea serpent? The universality of vertical undulation as an artistic solution for portraying wiggly movement in static two-dimensional media (and the rarity of vertical undulation in nature) hints that the Great Sea Serpent of modern legend could owe something to art. We will return to the influence of art, but first let’s explore the efforts during the classical period that we would call “science” today. Classical artists may not have recorded evidence for the existence of the modern sea serpent, but what of those ancient thinkers who attempted to accurately describe the animals of the air, land, and sea?

Sea Serpents in Classical Natural History

The cryptozoological hypothesis that immense sea serpents literally exist has an Achilles’ heel: extremely little demonstrated support in the historical record before the Enlightenment (when sea serpents suddenly burst into prominence in Scandinavia). The pioneering book

The Great Sea-Serpent, for example, was perfectly up front about the failure to identify sightings from antiquity. Author Anthonie Cornelis Oudemans wrote off the few possibilities he was aware of as misidentification errors and simply declared that he would “review only reports of no earlier date than the year 1500”

C.E.19Was Oudemans too hasty? It is unambiguously the case that the sophisticated scholars of classical Greece and Rome did, in fact, preserve accounts of sea monster sightings. For example, classical folklorist Adrienne Mayor has identified dozens of ancient references to allegedly real aquatic monsters.

20 But did these authorities describe creatures that are recognizably “sea serpents” in the modern sense? To qualify as sea serpents, creatures must (minimally) live in the sea and look like serpents. Some classical texts describe marine monsters that are not serpents. They include a giant man-eating sea turtle

21 and some clear references to whales (such as the orca enclosed in a harbor and battled by boats as entertainment under the Roman emperor Claudius).

22 Others describe serpentine creatures that did not live in the sea (such as a giant snake that allegedly fought Roman soldiers at a river in North Africa).

23Oudemans briskly dismissed the argument that the animals mentioned by Aristotle, Pliny the Elder, and other classical natural historians were sea serpents, considering them pythons, eels, and known species of sea-adapted snakes. This cavalier approach may seem hard to justify, but I think that he was correct: despite some serpent-like versions of the ketos in art, and despite many ancient references to sea monsters in general, classical history and literature can offer little to help the case for the sea serpent in particular.

Consider Aristotle. His meticulous

History of Animals (350

B.C.E.) is often cited in support of the sea serpent, but this is a stretch too far. The most frequently quoted passage refers simply to “some strange creatures to be found in the sea, which from their rarity we are unable to classify.” Fishermen apparently described some of these unidentified rarities as “sea animals like sticks, black, rounded, and of the same thickness throughout.”

24 This representation may sound suggestive to those sufficiently willing to cherry-pick, but it is vague to the point of meaninglessness. Another passage is much more clear—in that it clearly does not describe a sea serpent:

In Libya, according to all accounts, the length of the serpents is something appalling; sailors spin a yarn to the effect that some crews once put ashore and saw the bones of a number of oxen, and that they were sure that the oxen had been devoured by serpents, for, just as they were putting out to sea, serpents came chasing their galleys at full speed and overturned one galley and set upon the crew.

25Both Aristotle and Oudemans understood that this was an exaggerated, hearsay description of Africa’s native pythons. Such stories of land-based, big snakes were common and had nothing to do with sea monsters. Yet, they sound so tempting! As Bernard Heuvelmans’s respected book

In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents explains, this hyperbole has led to the widespread misuse of “various stories of gigantic snakes, but living on land, which many authors have tried hard to include in the sea-serpent’s dossier.”

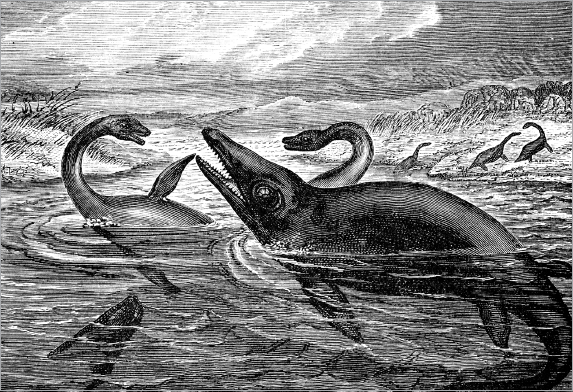

26As with stories of whales and sea monsters, ancient Greek lore about pythons was intertwined (and often interchangeable) with that of dragons. Consider an example from Greek epic poetry. When the legendary hero Jason approaches the grove of the Golden Fleece, the last challenge he must face is a vast serpent (

figure 5.3):

Directly in front of them the dragon stretched out its vast neck when its sharp eyes which never sleep spotted their approach, and its awful hissing resounded around the long reaches of the river-bank and the broad grove…. Women who had just given birth woke in terror, and in panic threw their arms around the infant children who slept in their arms and shivered at the hissing. As when vast, murky whirls of smoke roll above a forest which is burning, and a never-ending stream spirals upwards from the ground, one quickly taking the place of another, so then did that monster uncurl its vast coils which were covered with hard, dry scales.

27It is not surprising that Greek stories feature land-based mega-serpents. The Greeks had contact with some of the planet’s largest snakes, but not such close contact as to easily distinguish folklore from biology. In modern Africa, large pythons range widely below the Sahara (and may have been encountered in North Africa’s Mediterranean regions in classical times, as Aristotle reports). The African rock python (

Python sebea), in particular, which grows to lengths of 20 feet or more, is a “monster” even before the magnifying power of hearsay. Rock pythons occasionally hunt humans for food, with the largest specimens capable of swallowing an adult whole.

28Figure 5.3

The serpent guardian of the Golden Fleece regurgitates Jason, as Athena watches, on a red-figure cup painted by Douris, ca. 480–470 B.C.E. (Redrawn after Vatican 16545, Vatican Museum, Rome)

The armies of Aristotle’s student Alexander the Great conquered far to the east, invading India in 326

B.C.E. There, Alexander’s officers reported seeing snakes as large as 24 feet long and heard claims of snakes many times larger.

29 By the time the Roman military commander and naturalist Pliny the Elder compiled his

Natural History (ca. 77–79), stories of Indian mega-snakes had grown to describe “dragons”

30 fond of hunting elephants—indeed, of “so large a size that they easily encircle the elephants in their coils and fetter them with a twisted knot.”

31 (By the Renaissance, the dragon-versus-elephant idea had been applied to African pythons as well. Edward Topsell wrote in 1608 of the “enmitie that is betwixt Dragons & Elephants, for so great is their hatred one to the other, that in Ethyopia the greatest dragons have no other name but Elephant killers.”)

32Looking over this literature, Heuvelmans correctly concluded that classical tales “do not refer to the sea-serpent, even in the widest sense, but to other creatures which have nothing to with the case.”

33 This absence is conspicuous when contrasted with the way that classical knowledge of other, known sea animals expanded and improved over time. Aristotle and other natural historians eventually hammered down an accurate understanding of whales, distinguishing these animals from other sea monsters with the term

phallaina (the root of the Latin word

baleaena and the English term “baleen”). By the fourth century

B.C.E., Aristotle could describe how whales breathe air through a blowhole instead of gills, bear live young, and even provide milk for those young. No comparable understanding emerged for any sort of sea serpent. This suggests that there were no genuine sea serpents for classical informants to observe.

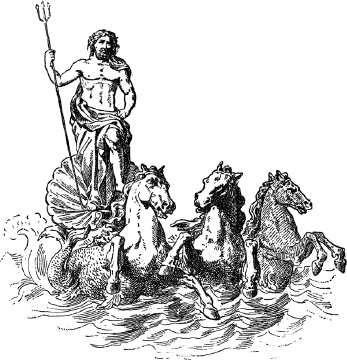

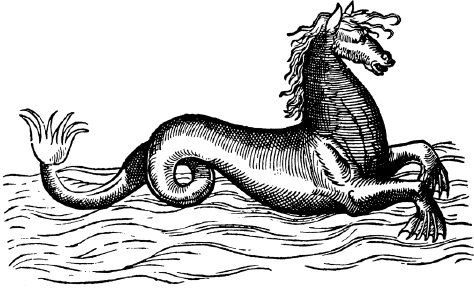

THE HIPPOCAMP: GRANDFATHER TO THE GREAT SEA SERPENT

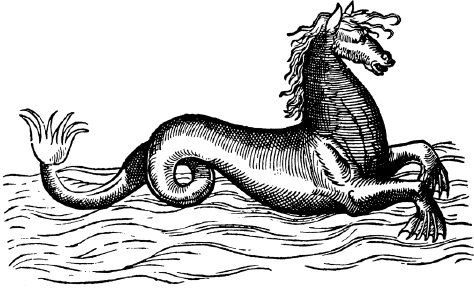

Cryptozoology has tended to overlook what I believe to be the pivotal classical example of a sea serpent–like creature: the

hippokampos or hippocamp (

figure 5.4). An imaginary mer-creature, the hippocamp combines the foreparts of a horse with a looping, coiled tail inspired by fish or dolphins (like the Capricorn that many people know from astrology, whose foreparts are those of a goat). Hippocamps appeared first on vases, coins, jewelry, sculpture, and other artworks from ancient Greece and Italy, where they were often used as a purely decorative element. In the 2,500 years that followed, they became a fixture in European art and literature—especially in heraldry. For example, a hippocamp appears on the coat of arms of Belfast, Ireland.

Developed by the Greeks, embraced by the Romans, and passed from country to country during the Middle Ages, the image of the hippocamp slowly mutated into something more than a decoration for vases. Over time, this fantasy creature became an allegedly real cryptid. In my opinion, the modern myth of the Great Sea Serpent (including the recent version, Cadborosaurus) is a cultural invention descended from the artistic tradition of the hippocamp.

Figure 5.4

Poseidon, the Greek god of the sea, rides a hippocamp on Attic black-figure pottery, ca. sixth century B.C.E.

Figure 5.5

The classical hippocamp and the modern cryptid Cadborosaurus share a general body plan, as well as such specific anatomical details as a mane and whale-like tail. (Various artists have regularly depicted both creatures with between one and several humps or tail arches.) (Illustration by Daniel Loxton)

It is not hard to spot a family resemblance.

34 Compare the typical hippo-camp with a modern composite drawing of Cadborosaurus (

figure 5.5). These creatures are a direct, one-to-one anatomical match—from the tips of their whale-like flukes, to their pectoral limbs, to their horse’s manes.

35 Here is a clear answer to some of the peskiest questions about the sea serpent: Why the preposterous vertical arches? Why the mane of a horse? Why the head of a horse (or, in some variants, a cow, sheep, or camel)? It is a puzzle that bothered me as a kid and has bothered me throughout my career as a skeptical investigator. Why would sea serpents look so much like horses? It turns out that the answer is simplicity itself. Like Jessica Rabbit in the film

Who Framed Roger Rabbit, sea serpents have their shape because they were, literally, “drawn this way.”

The horse-headed hippocamp motif first appeared in Greece during the Orientalizing period at around the same time as the Triton (or merman) and the

ketos-type sea monster. It is important to emphasize at the outset what hippocamps were not. They were not gods. They were not characters in myths. Most important, they were not believed to be real animals. The classical world did have a lively tradition akin to cryptozoology. Serious scholars like Aristotle and Pliny the Elder attempted to fold into natural history the fantastic creatures described in rumor, legend, and travelers’ tales from distant lands. Dragons, unicorns, and griffins fit into this tradition, as do ferocious

ketos sea monsters. Even mermen were reportedly spotted by eyewitnesses, but hippocamps were not.

Figure 5.6

Poseidon, standing on a shell chariot, being drawn through the sea by hippocamps.

Hippocamps existed almost exclusively in art, where they often were depicted as steeds for mythological beings associated with the sea (

figure 5.6). They appeared as an artistic motif at around the same time as the emergence of artwork that featured a similar-looking real-world fish: the spiral-tailed, horse-headed sea horse.

36 Indeed, these real and mythological creatures reflect each other so well that sea horses are classified as members of the genus

Hippocampus, giving these delicate little fish the unlikely designation “horse sea monster.” Recursively, the fantastical hippocamps may have been inspired by the fish—although the origin of the monster is unclear. Archaeologist Katharine Shepard reflected that interpreting the significance of the hippocamp is a “difficult problem, since he plays no part in any mythological tale”:

Some have thought that the horse was symbolic of the waves of the sea. Poseidon riding a hippocamp or Poseidon in a chariot drawn by hippocamps would then represent Poseidon borne by the waves. Another idea is that the monster is intended as a likeness of a real sea-horse, but our knowledge of sea-horses does not justify this theory. Probably the hippocamp is a purely fantastic monster, which served sometimes as a symbol of the sea. Often the animal seems merely to be used for decorative purposes.

37How did a decorative creature break free from the realm of art to take a central place in cryptozoology? Let’s trace that strange transformation.

The Hippocamp Spreads Across Europe

The hippocamp motif was adopted by the Romans and eventually diffused across Europe. The Romans themselves may have carried it to England and Scotland (

figure 5.7). They invaded Britain in 43

C.E. and ruled much of the island for almost four centuries. The cultural legacy of the Roman presence in Britain persisted long after the end of Roman rule. This influence is a plausible source of hippocamps found (for example) in Aberlemno, Scotland, where they add a decorative flourish to ninth-century Pictish relief sculpture.

38Figure 5.7 A section of the mosaic floor from the Roman Baths in Bath, England, ca. fourth century C.E. (Photograph by Andrew Dunn, via Wikimedia Commons. Released under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license)

The enduring popularity of classical literature helped carry the concept of the hippocamp into the Middle Ages and beyond. For example, the Roman poet Virgil wrote that the mythological Proteus

… rides o’er

The sea, drawn by strange creatures, horse before

Virgil was read everywhere in Christian Europe. (Likewise, the mosaics, paintings, and sculptures of antiquity were widely admired and copied long after the fall of the Roman Empire.)

An immensely popular Greek text called the

Physiologus was instrumental in transmitting the concept of the hippocamp. Composed in Alexandria, Egypt, between the second and fourth centuries,

40 the

Physiologus is a collection of legends about interesting and exotic animals from the fox to the unicorn—but it is not a work of natural history. The unknown compiler intended the

Physiologus to be read for moral instruction. Drawing material from the legends and natural history of classical antiquity, the

Physiologus reconceived each creature in the service of overt Christian allegory.

41 Appearing alongside such old favorites as the centaur, siren, and phoenix, the hippocamp (Hydrippus) became a symbol for Moses:

There is also a beast called the Hydrippus. The front part of his body resembles a horse, but from the haunch backwards he has the shape of a fish. He swims in the sea, and is the leader of all fishes. But in the Eastern parts of the earth there is a gold-coloured fish whose body is all bright and burnished, and it never leaves its home. When the fish of the sea have met together and gathered themselves into flocks, they go in search of the Hydrippus; and, when they have found him, he turns himself towards the East, and they all follow him … and they draw near to the golden fish, the Hydrippus leading them. And, when the Hydrippus and all the fish are arrived, they greet the golden fish as their King…. The Hydrippus signifies Moses, the first of the prophets.

42The Greek

Physiologus was soon translated into Ethiopian, Armenian, Syrian, Arabic, and Latin. From there, the evolution of the book got more complicated. (Translator Michael Curley dryly understates, “The influence of

Physiologus on the literature and art of the later Middle Ages is too long a story to be fully recounted here.”)

43 For our purposes, it’s enough to note that a rich and varied ecosystem of versions and adaptations emerged, with hand-drawn manuscripts in many languages spreading throughout Europe.

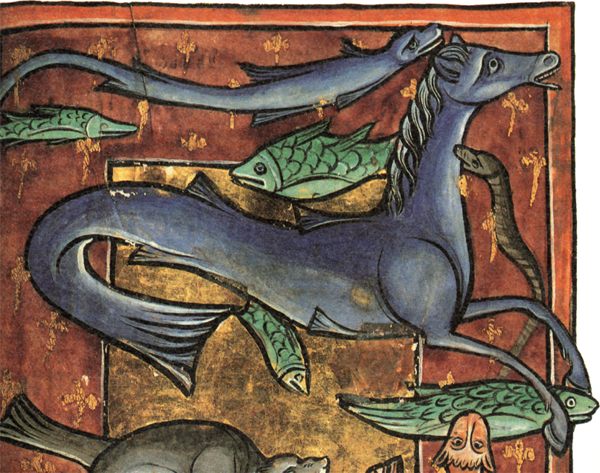

Figure 5.8 A hippocamp depicted in the Ashmole Bestiary, ca. 1225–1250. (MS. Bodl. 764, fol. 106r; reproduced by permission of the Bodleian Libraries, The University of Oxford)

“A major watershed in the later history of

Physiologus,” Curley continues, “is its incorporation into the encyclopedias and natural-historical compendia of the late Middle Ages.” In particular, the influential

Etymologies (ca. 623) of the archbishop and scholar Isidore of Seville drew heavily on the legends collected in the

Physiologus, while dropping most of the Christian allegorical content. In Isidore’s treatment, the hippocamp is rendered down from a Moses figure to an ordinary sea creature. Smack dab between whales and dolphins is the entry for “Sea-horses (

equus marinus), because they are horses (

equus) in their front part and then turn into fish.”

44 This demythologized version brought the fantastical hippocamp a step closer to its modern reinvention as a cryptid.

The tradition of compiling animal legends continued in a genre of twelfth- and thirteenth-century books referred to generically as the “bestiary” (book of beasts). Larger collections than the

Physiologus, they contain three times the content of the earlier books. Bestiaries include exotic monsters, but the central passages feature ordinary creatures made to serve Christian allegory. “For what is the good of a lesson that can only be taught by hearsay,” asks translator Richard Barber, “relating to a beast that no one has ever seen in the flesh? The longest sermons are devoted to topics drawn from everyday life: the ant and the bee display the virtues of humility, obedience and industry, the viper warns against the sin of adultery.”

45Bestiaries were hand-copied (and creatively improvised) from previous bestiaries, and they varied enormously. Some describe the hippocamp; in others, the hippocamp appears as an illustration. The lavishly gold-leafed Ashmole Bestiary, for example, features an illustration of the hippocamp in its general discussion of fishes (

figure 5.8).

The Hippocamp in Nordic Culture

The modern sea serpent legend was born out of Nordic culture, with its origin in medieval Iceland and its florescence in Enlightenment Norway.

THE ICELANDIC HROSSHVALR By the twelfth century, the Norse society of Iceland had adopted a belief in a creature called the hrosshvalr (horse whale), which was depicted as an unmistakable hippocamp. We will see that this innovation—the Nordic reimagining of the Greek hippocamp as a maned, horse-headed “real” marine monster—is a key to solving the modern mystery of the Great Sea Serpent.

As a maritime culture, the Norse naturally told tales of a great many sea monsters—including a huge, kraken-like creature called the

hafgufa—but even among these teeming monstrosities, the

hrosshvalr was considered especially savage. It was described in a twelfth-century text called

The King’s Mirror (

Konungs Skuggsjá), which was almost certainly intended to instruct the son of a Norwegian king.

46 Along with lessons in statesmanship and trade,

The King’s Mirror taught the unknown prince about useful species of whales and warned him of the dangerous monsters of the sea:

There are certain varieties that are fierce and savage towards men and are constantly seeking to destroy them at every chance. One of these is called hrosshvalr, and another raudkembingr. They are very voracious and malicious and never grow tired of slaying men. They roam about in all the seas looking for ships, and when they find one they leap up, for in that way they are able to sink and destroy it the more quickly. These fishes are unfit for human food; being the natural enemies of mankind, they are, in fact, loathsome.

Scholars have tended to identify these creatures as walruses or sea lions, although

The King’s Mirror specifies that the

hrosshvalr and

raudkembingr grow to “thirty or forty ells in length,” or about 67 to 90 feet. It’s probable that the words

hrosshvalr (horse + whale) and “walrus” (whale + horse) are etymologically related. (J. R. R. Tolkien, a philologist and the author of

The Lord of the Rings, struggled with the etymology of the term “walrus” for the

Oxford English Dictionary during his tenure with the dictionary in 1919 and 1920.)

47 It is possible that

hrosshvalr started out as a word for “walrus” and was later applied to a fanciful monster. Nonetheless, whatever the original meaning of “horse-whale,” the

hrosshvalr took on a familiar form, a form that it keeps to this day: when Flemish mapmaker Abraham Ortelius depicted the

hrosshvalr, he drew the creature as a classical hippocamp (

figure 5.9).

Figure 5.9 The hrosshvalr depicted by Abraham Ortelius on his map of Iceland, published in 1585.

Figure 5.10

A life-like interpretation of a hrosshvalr on an Icelandic stamp issued in March 2009. (Illustration by Jón Baldur Hlíðberg; image courtesy of Iceland Post)

Ortelius made historic contributions to cartography, creating the first modern atlas in 1570 (and later, incidentally, proposing continental drift). His depiction of the hippocamp as a living monster also marked a critical milestone in the formulation of the sea serpent. Ortelius lavishly populated his maps with monsters, many borrowed from the work of Olaus Magnus or harkening back to the curly-tailed

ketos. The map of Iceland that Ortelius published in 1585 teems with ferocious beasts, including our friend the

hrosshvalr. He described it as “sea horse, with manes hanging down from its neck like a horse. It often causes great scare to fishermen.” In his illustration, the hippocamp has long webbed toes and a finny frill on the back of its horse-like forelimbs—a form that it often takes in heraldry. (In other heraldic uses, the hippocamp may have front flippers instead of webbed feet.) The

hrosshvalr still has essentially this shape, although now filtered through the sensibilities of modern fantasy art. It is depicted, for example, as a maned, flippered, hippocamp-like animal on a stamp issued by the Icelandic government in 2009 (

figure 5.10).

THE MIDGARD SERPENT The hippocamp-inspired

hrosshvalr of medieval Iceland is not the only relevant source for the Great Sea Serpent. We must also consider a vast entity from Norse mythology called Jörmungandr: the World Serpent or Midgard Serpent. Jörmungandr was a child of the Norse god Loki. Cast down into the watery abyss by Odin, the ruler of the gods, Jörmungandr grew into a serpent so large that his body stretched around Earth. According to an older story recorded in the medieval Norse

Prose Edda, the god Thor successfully fished for Jörmungandr using a huge hook and an ox’s head for bait (

figure 5.11).

Figure 5.11

Jörmungandr, the World Serpent or Midgard Serpent, takes the ox’s head bait dangled by the Norse thunder god, Thor. (Redrawn from a seventeenth-century Icelandic manuscript)

When the modern sea serpent legend eventually made its way into academic debates (starting in the 1750s with a treatment written by Bishop Erich Pontoppidan of Norway), scholars were quick to suggest that it could be the Jörmungandr myth repackaged for a scientific age. Discussing the tale of Thor fishing for the Midgard Serpent, Bishop Thomas Percy noted in 1770, “We see plainly in the … fable the origin of those vulgar opinions entertained in the north, and which Pontoppidan has recorded concerning the craken and that monstrous serpent described in his

History of Norway.”

48 A century later, this view was still invoked as an explanation for the sea serpent. In 1869,

The New American Cyclopedia held:

It is important to observe that the idea of a sea serpent certainly originated in northern Europe, and was clearly mythological in its first conception. The Midgard serpent, offspring of Loki, which girds the world in its folds and inhabits the deep ocean till the “twilight of the gods,” when it and Thor will kill each other, plays a conspicuous part in the

Edda; and the gradual degradation of the idea from mythology to natural history in its native seats may be traced in Olaus Magnus and the later sagas, till the Latin of Pontoppidan gave it currency in Europe with the natural additions of popular fancy.

49Is this view correct? Is the modern sea serpent descended from Jörmungandr? It is probably not a coincidence that a culture with a stupendously large mythological sea serpent later invented a stupendously large cryptozoological sea serpent, but the exact relationship is not entirely clear. (As early as 1822, attempts were made to turn the argument on its head: perhaps a species of serpentine cryptid gave rise to the Norse myth, rather than the other way around.

50 As A. C. Oudemans elaborated, “All fables have their foundation in facts, or in objects of nature, and it is plausible that the Norwegians had met with the sea-serpent before the fable of Thor’s great Serpent was inserted into their

Eddas.”)

51It is certainly plausible, even likely, that the Jörmungandr myth could be among the roots of the Norwegian sea serpent legend. In turn, the Midgard Serpent can be plausibly interpreted as a regional iteration of primordial dragon myths, such as the Babylonian Tiamat and the biblical Leviathan. It’s worth noting that our sources for the Midgard Serpent and other Norse myths date from well into the Christianization of the Nordic countries. Written by a Christian,

The Prose Edda begins with the words, “In the beginning God created heaven and earth and all those things which are in them; and last of all, two of human kind, Adam and Eve, from whom the races are descended.”

52Albertus Magnus

Whatever the true source and impact of the Jörmungandr myth, belief in the hippocamp continued to spread and develop. Some of Europe’s greatest intellectual lights took up the topic of the mer-horse, including the natural philosopher Albertus Magnus (Albert the Great).

Born at the dawn of the thirteenth century, Albertus worked in a twilit age of both deep superstition and remarkable advances (such as windmills, ship rudders, and, at the end of his life, papermaking in Italy). Albertus started off slowly. “For the first thirty years of his life he appeared remarkably dull and stupid,” according to Charles Mackay.

53 He became a Dominican friar and eventually a bishop—and, along the way, one of the medieval world’s most celebrated scholars, remembered today as a towering prescientific thinker.

54 (The famed Catholic theologian Thomas Aquinas was a student of Albertus Magnus.)

Albertus Magnus is best known for his encyclopedic

De animalibus, which built on the work of Aristotle (with material from other authorities, including insights from Albertus himself). Among the menagerie of real aquatic animals and mythical marine monsters is our old friend the hippocamp, described as a predator, “alive” and well at the cutting edge of scholarship that would one day give rise to zoology and cryptozoology: “equus maris (Sea horse) is a marine animal whose foreportion takes the form of a horse and rear parts terminate like a fish. It is a pugnacious creature, inimical to many marine species, and its diet consists of fish. It has an abject fear of man; outside the water it is utterly helpless and dies soon after being removed from its native element.”

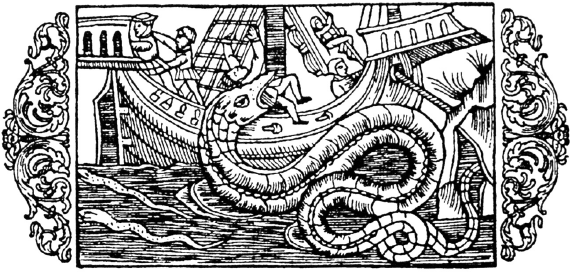

55Olaus Magnus

The now-familiar modern sea serpent had no existence as a cryptid during the Middle Ages. Medieval witnesses saw many other menacing monsters of the deep, including hippocamps, but not the Great Sea Serpent. On the contrary, the Great Sea Serpent turns out to be a fish story of relatively recent composition. An important milestone in its development came with the scholarship of Olaus Magnus, the archbishop of Uppsala in Sweden. For many commentators, Olaus is considered the original sea serpent author, although we’ll see that the honor does not belong only to him.

Around the time that Nicolaus Copernicus proposed his heliocentric model of the solar system, Olaus Magnus created an advanced map of the Scandinavian countries and wrote a lengthy book about the people, customs, and animals of those lands. Known in English as

A Description of the Northern Peoples (1555), the book became the standard reference on Scandinavia. It also provided the final stage set for the modern sea serpent (although the curtain would not fully open for a further 200 years). By then, the Scandinavian reimagining of the Greek hippocamp as a “real” sea monster was itself a centuries-old tradition. Like Albertus Magnus before him, Olaus Magnus described this

Equus marinus as a genuine, living animal: “The sea-horse may be observed fairly often between Britain and Norway. It has a horse’s head, utters a neighing sound, has cloven hoofs like a cow, and seeks its pasture as much in the sea as on land. It is seldom caught, even though it reaches the size of an ox. Lastly, its tail is bifurcated like a fish’s.”

56Olaus also presented a menagerie of other exotic sea monsters, including a “monstrous Hog” with “four feet like a Dragons, two eyes on both sides in his Loyns, and a third in his belly, inclining toward his navel.” Another seemingly unlikely creature was “a Worm of blew and gray colour, that is above 40 cubits [60 feet] long, yet is hardly so thick as the arm of a child.” Oddly enough, this worm (which he claimed to have regularly seen himself) appears to be a real animal: the thin nemertean bootlace worm (

Lineus longissimus), which can grow longer than 100 feet.

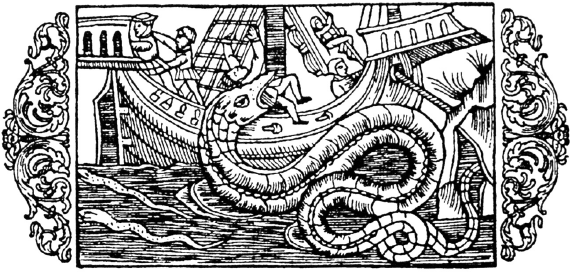

57But it is to another Olaus Magnus monster that we must turn—a land-based Norwegian serpent that, Olaus said, sometimes entered the water to hunt. This has become one of the most-quoted passages in the vast sea monster literature:

Those who do their work aboard ship off the shores of Norway, either in trading or fishing, give unanimous testimony to something utterly astounding: a serpent of gigantic bulk, at least two hundred feet long, and twenty feet thick, frequents the cliffs and hollows of the seacoast near Bergen. It leaves its caves in order to devour calves, sheep, and pigs, though only during the bright summer nights, or swims through the sea to batten on octopus, lobsters and other crustaceans. It has hairs eighteen inches long hanging from its neck, sharp, black scales, and flaming-red eyes. It assaults ships, rearing itself on high like a pillar, seizes men, and devours them. It never appears without denoting some unnatural phenomenon and threatening change within the state; the deaths of princes will ensue, or they will be hounded into exile, or violent war will instantly break out.

58This serpentine animal appears in virtually every book and documentary on the topic of sea serpents, cited as the canonical first important record of the Great Sea Serpent. It is easy to understand why so many authors fall into this trap. A maned snake that snatches screaming sailors from the rigging? Sure sounds like the monster of modern legend! But it isn’t—not quite. Not yet.

Looking back at Olaus Magnus’s account, pioneering sea serpent author A. C. Oudemans was happy in 1892 to take those elements that conformed to his own vision of the sea serpent—and to discard the rest arbitrarily, decreeing, for example, the testimony of “its devouring hogs, lambs, and calves, and its appearance on summer nights on land to take its prey to be a fable.”

59 In constructing his cherry-picked version, Oudemans fundamentally misrepresented the dragon-like snake that Olaus had described. According to Olaus, this monster does not venture onto land to take its prey, but lives and hunts on land (in “cliffs and hollows of the seacoast”) and occasionally enters the water to harvest seafood (such as the sailors it cracked “like sugared almonds,” as a magazine article put it in 1843).

60 This lifestyle is firmly underlined by the accompanying illustration in

A Description of the Northern Peoples, which clearly shows the serpent emerging from its cave on land (

figure 5.12)!

Figure 5.12 The serpent depicted in Olaus Magnus’s Description of the Northern Peoples emerges from a cave on land to prey on the crews of passing ships.

A serpent, sure. The modern sea serpent? No. Olaus Magnus’s snake should be viewed as a component legend, a root. It has the mane of the hippo-camp, and it is a menace to ships, but Olaus Magnus was clear in describing it as a land-based monster. It is, in short, a lindorm—one of the standard gigantic snakes or dragons in Scandinavian folklore.

It’s important to realize as well that supernatural phenomena were fundamental components of

lindorm stories of this period. When Olaus Magnus wrote that the appearance of the serpent foretells a major upheaval, such as a royal death or a major war, he was not kidding—and he was not just tacking on some bit of superstitious gloss to the end of a naturalistic wildlife sighting. The supernatural significance is what those stories are about; the naturalism that cryptozoologists impose on them is the artificial gloss. Nonetheless, such revisionist demystification is a long-standing (and ongoing) tradition.

61 When science-minded Bishop Erich Pontoppidan repeated Olaus Magnus’s snake story 200 years later, he felt it was obvious that Olaus “mixes truth and fable together … according to the superstitious notions of that age.”

62 Bernard Heuvelmans likewise pooh-poohed the supernatural aspects of Olaus Magnus’s account (“We may smile at His Eminence’s naïveté”), but the truth is that such arbitrary editorializing is reckless. Folklorist Michel Meurger is scathing of the way that Heuvelmans and other cryptozoologists omit or downplay the supernatural, calling it a “gross distortion” of these stories.

63The Evolving Sea Serpent

Two more centuries would go by before the parallel currents of folklore described by Olaus Magnus—the lindorm and Scandinavian iterations of the hippocamp—would converge to form the modern sea serpent legend. During those 200 years, scholars continued to discuss the hippocamp by its many names: “hippocamp” or “hyppocamp” (English); hippokamos or Hydrippus (Greek); sjø-hest (Norwegian); hroshvalur, hrossvalur, or roshwalr (Icelandic); Equus marinus, Equus aquaticus, or Equus bipes (Latin); and cheval marin (French). Following those discussions is difficult, complicated by the fact that most European cultures had their own version of the hippocamp-style monster, plus related (yet distinct) supernatural, kelpie-type water-horses associated with bodies of freshwater. In most of the languages, the word for the hippocamp-monster is the same as the name for delicate little fishes: sea horse. And, to make things even more bewildering, many hippocamp-type monsters are interchangeable with walruses!

In all this confusion, the English-language cryptozoological and skeptical literatures have typically treated the hippocamp-type monsters as rather marginal creatures with no particular relationship to the sea serpent. Still, I am not the first to note that the old Scandinavian mer-horse traditions became part of the formulation of the new Scandinavian sea serpent. Referring to the work of Norwegian writer Halvor J. Sandsdalen, Michel Meurger explains that the modern sea serpent represents a hybridization, a “fusion of several fabulous creatures originally clearly differentiated in Norwegian folklore”:

64 the terrifying half-fish, half-horse monster called the

havhest (another Scandinavian synonym for “hippocamp”) blended with the

lindorm, “a land snake blown to gargantuan proportions.”

We’ll come to that moment of fusion—the moment the modern sea serpent was born—shortly. For now, let’s look more closely at the evolution of the hippocamp as an allegedly real monster at the dawn of the scientific era.

Some authorities of the late Middle Ages and early modern period took the mer-horse to be a fact of natural history, on the sensible basis that people sometimes saw them. Others correctly linked the folk belief in horse-headed sea monsters to the classical concept of the hippocamp. French naturalist Pierre Belon and Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner were among the skeptics. A specialist in marine animals, Belon straightforwardly identified the hippocamp as the “fabulous horse of Neptune” (

figure 5.13).

65 As we have seen, Olaus Magnus argued in 1555 that the hippocamp was a genuine animal, but Gesner (an even more towering figure in zoological history) accepted Belon’s debunking analysis. Gesner’s encyclopedia

Historiae animalium (1551–1558) was the most ambitious natural history text written since the fall of Rome. Gesner repeated Belon’s argument that modern sea horse sightings are based on an invented classical fancy:

Figure 5.13 The hippocamp as depicted in both Pierre Belon’s De aquatilibus, a treatise on fishes, and book 4 of Conrad Gesner’s Historiae animalium.

The Ancients took great liberties with their charming fables, crafted to conceal the truth yet be believed and cloud the credulous minds of men in a haze of nonsense…. Those who put their faith in the silly pictures of the ancients are deceived…. It all comes from the desire of princes for the fame of their name and the wonder of scholars: since they wished to signify their dominion over land and sea, they joined together the two animals that symbolize these elements, horse and dolphin, which became a monstrous fusion of marine detritus they still call by the name of Hippocampus.

66Gesner was much less skeptical in his treatment of other monsters discussed by Olaus Magnus. He repeated the descriptions and illustrations of two species of sea serpent: a smaller type (about 30 or 40 feet long) and the dragon-like mega-serpent portrayed by Olaus:

On the same map there is another sea-serpent, a hundred or two hundred feet long … or three hundred … which sometimes appears near Norway in fine weather, and is dangerous to Sea-men, as it snatches away men from ships. Mariners tell that it incloses ships, as large as out trading vessels … by laying itself round them in a circle, and that the ship is then turned upside down. It sometimes makes such large coils above the water, that a ship can go through one of them.

67Gesner’s otherwise faithfully redrawn version of the illustration in

A Description of the Northern Peoples makes the critical change of moving the monster to open water, rather than emerging from a cave on shore (

figure 5.14). The illustration of the smaller serpent shows another modern feature: the serpent floats with its coils arching cartoonishly out of the water (

figure 5.15). As Bernard Heuvelmans later noted, this now-canonical detail is fundamentally ridiculous: “Perhaps the great number of humps in the great sea serpent is the result of the naiveté or incompetence of the illustrators. Gesner’s picture of his ‘Baltic’ sea serpent certainly leads one to think so, for the way the animal floats almost entirely out of the water would be mechanically impossible for anything but a balloon.”

68Alongside the fledgling Scandinavian idea of the sea serpent, belief in the monstrous sea horse continued. Surgeon Ambroise Paré took up the topic in his book

Des monstres et prodiges (1573). Caught between the superstition of the Middle Ages and the first stirrings of proto-scientific empiricism, Paré was intensely interested in medical marvels (gruesome birth defects, in particular) but also turned his attention to black magic, celestial portents, and monsters. After discussing several sorts of mermen, Paré described the hippocamp as a living creature: “This marine monster having the head, mane and forequarters of a Horse, was seen in the Ocean sea; the picture of which was brought to Rome, to the Pope then reigning.”

69 (It’s interesting how these ideas cluster: after 2000 years, classical Greek Tritons and hippocamps were still swimming alongside each other in the European imagination.) It was around this time, in 1585, that mapmaker Abraham Ortelius depicted the Icelandic

hrosshvalr as a classical hippocamp, “with manes hanging down from its neck like a horse.”

Figure 5.14 The land-based mega-serpent of Olaus Magnus becomes the ocean-going sea serpent of Conrad Gesner.

Figure 5.15 Conrad Gesner’s smaller type of sea serpent, as reproduced in Edward Topsell’s

Historie of Serpents.

As the infant scientific tradition began to wobble to its feet, so too did a related tradition that I work in: what is now called scientific skepticism, or the critical examination of popular beliefs, especially of paranormal claims.

70 Scientifically inclined writers began to ask which beliefs could be supported by empirical evidence and which were baseless superstitions. These attempts themselves often amounted to little more than reactionary scorn, and many of them proved to be as inaccurate as the claims they were critiquing. In England, physician Sir Thomas Browne’s book

Pseudodoxia Epidemica: Or, Enquiries into Very Many Received Tenets and Commonly Presumed Truths (1646; also called

Vulgar Errors) blends religious reasoning, the new empirical spirit, and ancient wisdom to produce a wonderful hit-and-miss prototype of the skeptical genre. Browne was quite right to doubt the “very questionable” claims that chameleons consume nothing but air and that the “flesh of Peacocks corrupteth not,” and he likewise nailed the falsity of the belief in hippo-camps. In his day, the sea horse was cited as proof of the folkloric notion that all the animals of the land were reflected by counterparts in the sea. Browne would have none of it, retorting scornfully, “As for sea-horses which confirm this assertion; in their common descriptions they are but Grotesco deliniations which fill up empty spaces in maps, and meer pictorial inventions, not any physical shapes.” He insisted that the folkloric sea horse was identical to the classical hippocamp.

71 (Browne emphasized that this mythical sea horse was distinct from the walrus and the curly-tailed fish, both of which were also called sea horse—as was, I might add, the hippopotamus in many medieval sources. I can’t help but empathize with Browne’s frustration: these several conflated creatures are a hassle to disentangle.)

Despite the skeptics, the belief in the monstrous sea horse persisted throughout European culture. For example, a quick-tempered Jesuit missionary named Louis Nicolas described the hippocamp as an animal living in Canada. Nicolas traveled extensively within Canada between 1664 and 1675 and produced his

Codex canadensis (a hand-drawn, seventy-nine-page document depicting the animals and aboriginal peoples of Canada) around 1700.

72 Nicolas showed an unambiguous classical hippocamp, matter of factly drawn alongside a beaver (

figure 5.16), as a “sea-horse which is seen in the fields on the banks of the Chisedek River, which empties into the Saint Lawrence.”

73By that time, the hippocamp had endured for two millennia, evolving from a purely artistic creature of fantasy to a monster accepted as real by scholars and regular folks across Europe and beyond. And it was not done yet.

THE BIRTH OF THE SCANDINAVIAN SERPENT

The Scandinavian sea serpent was finally born at the end of the seventeenth century. It existed then only as a regional monster, but the moment of fusion had come. As the Scandinavian serpent matured, German scholar Adam Olearius recorded a third-hand sighting around 1676 (“on the Norwegian coast, he saw in the calm water a large serpent, which seen from afar, had the thickness of a wine barrel, and 25 windings”), and historian Jonas Ramus recorded another sighting in 1698.

74The fully modern reformulation of Olaus Magnus’s shore-dragon as a gigantic, fully aquatic marine serpent with arching coils and a mane (the sea serpent form that survives as the cryptid Cadborosaurus) finally emerged as an established part of Norwegian folklore in 1694, when it was recorded in Hans Lilienskiold’s hand-scripted and gorgeously painted four-volume

Speculum boreale (

Northern Mirror). Lilienskiold was a high government official whose writing explored the culture, geography, and wildlife of the northernmost parts of Norway.

75 The

sjø-ormen (sea-worm), Lilienskiold wrote, “cannot be considered anything less than a bad vermin which often curves 236 feet in quiet seas, so it looks like a number of ox-heads have been thrown into the water.”

76 Crucially, Lilienskiold’s sea serpent featured a “light-grey mane which goes a fathom down below the neck,” thereby merging the parallel traditions of the hippocamp, the serpentine

lindorm, and the unnamed monsters of the sea. In a remote corner of Norway, a hybrid folkloric monster had been born.

Figure 5.16 The hippocamp as cheval marin in Louis Nicolas’s Codex canadensis. (Collection of the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma)

This new kind of sea serpent had what it took to become a star. All it needed was a promoter, a well-positioned publicist. That promoter was Bishop Erich Pontoppidan.

Erich Pontoppidan

Two hundred years after Olaus Magnus, the sea serpent was an established part of folk belief in Scandinavia—and only there. This point deserves boldfacing and underlining: the sea serpent was an exclusively Scandinavian creature, a cultural relative of the Icelandic

hrosshvalr and

havhest traditions. As Bernard Heuvelmans explained, “The sea-serpent was rarely heard of except in Scandinavia. There it was considered as a real animal and elsewhere as a Norse myth.”

77Then everything changed. The man responsible was Erich Pontoppidan, the bishop of Bergen in Norway from 1747 to 1754. Pontoppidan was not only a highly placed clergyman, but also a reputable member of the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences. For this reason, it made a splash when his two-volume

Natural History of Norway boldly argued for the flesh-and-blood reality of “the Mer-maid, the great Sea snake, of several hundred feet long, and the Krake[n] whose uncommon size seems to exceed belief.”

78 His advocacy for these creatures caught the imagination of the world. In particular, Pontoppidan’s sea serpent took off as a global popular mystery—igniting a scientific debate that would rage through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and continue among cryptozoologists in the twentieth and twenty-first.

When Pontoppidan turned his considerable talents to the discussion of the sea serpent, the Norwegian coast remained “the only place in Europe visited by this strange creature.”

79 But there, sea serpents were already an entrenched part of popular culture. For example, Pontoppidan quoted a treatment by the foremost Norwegian poet of the previous generation, Petter Dass:

The great Sea Snake’s the subject of my verse,

For tho’ my eyes have never yet beheld him,

Nor ever shall desire the hideous sight;

Yet many accounts of men of truth unstain'd,

Whose ev'ry word I firmly do believe,

Shew it to be a very frightful monster.

Many Norwegians accepted the reality of the sea serpent, while skeptics, who “are enemies to credulity, entertain so much the greater doubt about it.” Either way, by then everyone in Norway had heard of the legendary monster. As Pontoppidan reported, “I have hardly spoke with any intelligent person” who was not able to give “strong assurances of the existence of this Fish”—and to describe it.

80 That sea serpents had become a widely familiar, culturally available explanation for ambiguous or unfamiliar sights at sea should have given Pontoppidan pause, but he seems not to have realized the implications. Instead, he built his case on the aggregate of sighting reports, just as cryptozoologists do, citing “creditable and experienced fishermen, and sailors, in Norway, of which there are hundreds, who can testify that they have annually seen” sea serpents.

81 He was impressed by the way in which eyewitnesses “agree very well in the general description,” adding that “others, who acknowledge that they only know it by report, or by what their neighbors have told them, still realize the same particulars.”

82 This was a critical error. Pontoppidan treated cultural sea serpent lore as a

confirmation of eyewitness testimony, rather than as a

generator of sighting reports.

Be that as it may, some of the sightings were spectacular, leading the bishop to believe that sea serpents grew to a whopping 600 feet long. Witnesses also persuaded him that the necks of Norwegian serpents featured “a kind of mane, which looks like a parcel of sea-weeds hanging down to the water” (

figure 5.17). Fifty years after Hans Lilienskiold first described the truly modern sea serpent, the

hrosshvalr- and

havhest-derived mane persisted as a key feature of the folk belief (and, by virtue of looking like seaweed, provided an obvious source for mistaken sightings).

This cultural DNA from the hippocamp is glaringly obvious in Pontoppidan’s primary case study: the sworn testimony of naval officer Lawrence de Ferry. As a science-minded scholar, Pontoppidan was a voracious seeker of information who combed the literature, wrote letters, and questioned widely along the docks. “Last Winter,” he wrote,

I fell by chance in conversation on this subject with captain Lawrence de Ferry … who said he doubted a great while, whether there was any such creature, till he had the opportunity of being fully convinced, by ocular demonstration, in the year 1746. Though I had nothing material to object, still he was pleased, as a further confirmation of what he advanced, to bring before the magistrates, at a late sessions in the city of Bergen, two sea-faring men, who were with him in the boat when he shot one of these monsters.

83Figure 5.17 The maned sjø-ormen (sea-worm), drawn by Hans Strom, in Erich Pontoppidan’s Natural History of Norway.

Ferry wrote a statement describing his encounter, and his men swore before the magistrates that the statement was correct. Ferry had, the statement said, been at sea on a calm day when his eight rowers told him that “there was a Sea-snake before us.” He ordered the men to intercept the creature and “took my gun, that was ready charged, and fired at it.” The animal dived, leaving blood in its wake. “The head of this snake,” Ferry swore, “which it held more than two feet above the surface of the water, resembled a horse…. It had … a long white mane that hung down from the neck to the surface of the water. Beside the head and neck, we saw seven or eight folds or coils of this Snake, which was very thick … there was about [6 feet] distance between each fold.”

What did Ferry and his men see? It is interesting to speculate, as did skeptical naturalist Henry Lee: “The supposed coils of the serpent’s body present exactly the appearance of eight porpoises following each other in a line. This is a well-known habit of some of the smaller cetecea.”

84 (I have seen this effect, and it is shockingly compelling. More likely suspects, however, would be the seals common to the Norwegian coast.) In any event, “the horse-like features of the sea-serpent’s head were common knowledge,” as folklorist Michel Meurger notes. “Therefore, Ferry’s assertion is proof only of a traditional interpretation of a sighting he had six years prior to his official statement. This is too long a time to have a fresh recollection but more than enough time to blend memories with collective stereotypes.”

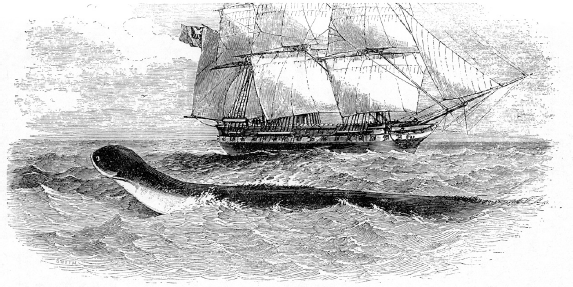

85The real importance of Ferry’s story is its subsequent role as a template. This widely publicized, often-translated, and precedent-setting sighting was the first credible eyewitness account to reach beyond Scandinavia, and it helped to lock in the canonical image of the sea serpent for the English-speaking world: multiple humps or coils, combined with the head and mane of a horse.

In the centuries since the publication of

The Natural History of Norway, Pontoppidan has often been criticized for his credulity. “Indeed,” wrote Heuvelmans, “the Bishop of Bergen was treated as a liar as arrant as Münchhausen.”

86 Other critics have been kinder. “The Norwegian Bishop,” granted Lee, “was a conscientious and painstaking investigator, and the tone of his writings is neither that of an intentional deceiver nor of an incautious dupe. He diligently endeavoured to separate the truth from the cloud of error and fiction by which it was obscured; and in this he was to a great extent successful.”

87 I have argued that quite a bit of Pontoppidan’s work can be regarded as early “scientific skepticism.”

88 He advocated for science literacy, pointedly critiquing his clerical brethren for “supercilious neglect” of knowledge of the physical world. Pontoppidan even went out of his way to investigate and correct popular falsehoods, such as the idea that bottomless whirlpools penetrate through the entire Earth and the already ancient legend that the Barnacle Goose hatches out of trees or rotten wood.

Pontoppidan was no slouch, so it is not surprising that he zeroed in on a key problem for his sea serpent: its cultural specificity:

Before I leave this subject, it may be proper to answer a question that may be put by some people, namely, what reason can be assigned why this Snake of such extraordinary size, &c. should be found in the North sea only? For, according to all accounts from seafaring people, it has never been seen anywhere else. Those who have sailed in other seas in different parts of the globe, have, in their journals, taken particular notice of other Sea-monsters, but not one of them mentions this.

89Many societies share the ocean, but only one encounters sea serpents. That is such a screaming, flashing, gigantic red flag that readers may be forgiven if they find Pontoppidan’s answer to it unconvincing. He simply asserted that “when the thing is confirmed by unquestionable evidence, and is found to be true,” then armchair objections are beside the point. Moreover, Pontoppidan argued that “this objection requires no other answer, than that the Lord of nature disposes of the abodes of his various creatures, in different parts of the globe, according to his wise purposes and designs, the reason of his proceedings cannot, ought not to be comprehended by us.” This dodge seems to me like the clergyman in Pontoppidan inappropriately pulling rank on the scientist.

THE GREAT SEA SERPENT

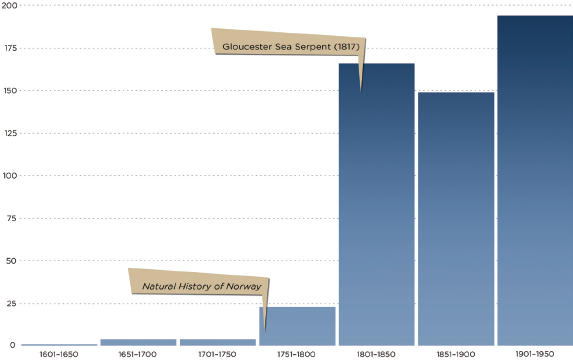

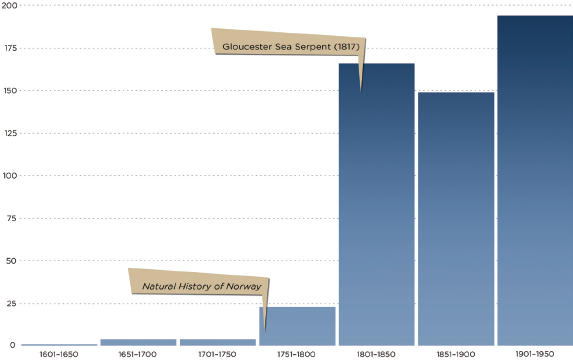

Erich Pontoppidan’s book was the critical turning point for the sea serpent: a Scandinavian phenomenon that burst forth onto the world stage to become an enduring part of popular culture. (I can’t help but think of the Swedish pop band ABBA.) To understand what a breakthrough this was, consider Bernard Heuvelmans’s overview of the sighting database (

figure 5.18). He estimated that in the centuries before the publication of Pontoppidan’s

Natural History of Norway, there were only nine dated and documented sightings of sea serpents in all of history. After Pontoppidan? “The number increases to twenty-three between 1751 and 1800 but they do not become really frequent until the first half of the nineteenth century: 166 from 1801 to 1850 and 149 from 1851 to 1900. The rate did not drop in the twentieth century, for there were 194 between 1901 and 1950.” Heuvelmans noted that the trend was continuing in the 1960s, when he compiled the statistics. Assuming that one-third of sightings record misidentification errors or hoaxes, he estimated that “this makes 100 sightings every fifty years, an average of two a year, right up to the present.”

90

Figure 5.18 Sightings of sea serpents, 1600–1950, by fifty-year intervals, according to Bernard Heuvelmans.

This strikes me as exceptionally funny in two respects. First, Heuvelmans’s assumption that two-thirds of claimed sightings are genuine was surely on the optimistic side; after all, it’s not known that there has been even one genuine sea serpent sighting—ever. Second, the pattern he described is clearly that of a pop-culture phenomenon. By his own admission, sea serpents basically did not exist before Pontoppidan’s book made them famous; since then, they have been seen regularly and increasingly.

The Natural History of Norway launched the sea serpent to stardom; from there, it entered the self-sustaining fame cycle that perpetuates UFOs, Bigfoot, and other popular mysteries.

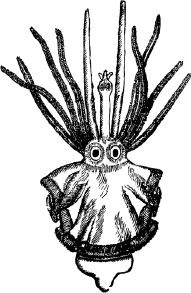

The Stronsay Beast

For as long as humans have walked beside the sea, they have marveled at the strange things that sometimes wash ashore. “During the rule of Tiberius, in an island off the coast of the province of Lyons the receding ocean tide left more than 300 monsters at the same time, of marvelous variety and size,” recorded the Roman natural historian Pliny the Elder.

91 Similarly, a pamphlet published in 1674 describes a “Strange Monster or Wonderful Fish” that washed up on a beach in Ireland (

figure 5.19). The description and illustration clearly identify the animal as a large squid, 19 feet in length (including the arms) “and in Bulk or Bigness of Body somewhat larger than a Horse.” (The anonymous author of the pamphlet cheekily added that “some Zealots hearing of a strange Creature … took it for the Apocaliptical Beast, and fancied the Pope was landed in person.”)

92Figure 5.19

The “Strange Monster or Wonderful Fish” that washed ashore in Ireland in October 1673.

Figure 5.20 The sketch of the Stronsay Beast drawn by an eyewitness. (Redrawn from Memoirs of the Wernerian Natural History Society 1 [1811])

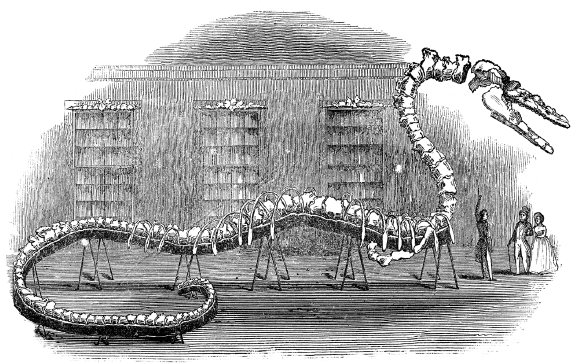

With the global publicity for Erich Pontoppidan’s sea serpent, strange carcasses took on new meaning. When a huge, vaguely whale-like animal washed up on Stronsa (now called Stronsay, an island off the northern tip of Scotland) in 1808, it was immediately identified as “a sea-snake with a mane like a horse”—and, indeed, the case seemed clear. Reportedly measured at a bulky yet sinuous 55 feet in length, with a long neck and a mane, there seemed little room to doubt that this was a creature unknown to science. Multiple sworn statements and an eyewitness sketch seemed to clinch the case (

figure 5.20). And then Scottish naturalist John Barclay stepped in to confirm that it “appeared to be the Soe-Ormen described above half a century ago, by Pontoppidan, in his

Natural History of Norway,” assigning it to a brand-new genus and species:

Halsydrus pontoppidani (Pontoppidan’s sea-snake).

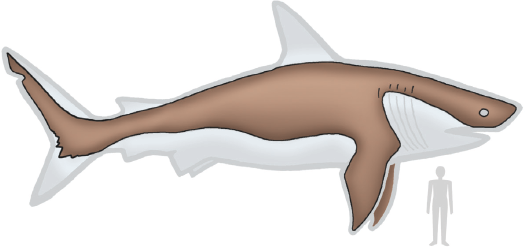

93Alas, nothing was as it seemed. Today, Barclay’s

Halsydrus pontoppidani is remembered alongside

Nessiteras rhombopteryx (proposed for the Loch Ness monster),

Hydrarchos sillimani (an alleged fossil sea serpent), and

Cadborosaurus willsi as a premature taxonomic misstep. The problem? The creature rotting on the Stronsay beach, scavenged by wheeling gulls, was a basking shark. The animal’s skull, several vertebrae, and other samples were sent to Everard Home, a surgeon and leading scientist who had recently received the Royal Society of London’s prestigious Copley Medal. With these specimens, Home was able to firmly identify the animal as a basking shark and to ascertain that the drawing and descriptions were wildly inaccurate distortions of the anatomy of the carcass. So stark was the discrepancy between the eyewitness testimony and the forensic evidence that the Stronsay Beast has lived on as a cautionary tale. “There can be little doubt that this creature was, actually, an enormous basking-shark, partly decomposed,” wrote sea serpent advocate Rupert Gould, “but the original reports are so curious, and the accepted explanation so much at variance with them, that the case deserves more than a cursory mention, if only as an instance of how misleading it is possible for honest testimony to be.”

94

Figure 5.21 It is typical for a decaying basking shark to resemble a plesiosaur. (Illustration by Daniel Loxton)

But was Home’s analysis accurate? Barclay did not think so. He published a rebuttal, objecting that the head of a basking shark is 5 feet across, while the skull of the Stronsay Beast was only 7 inches wide. But Barclay had fallen into a trap that has misled people ever since. The huge, gentle basking sharks—like all sharks—have skeletons made of cartilage, rather than bone. Moreover, basking sharks are filter feeders (similar to humpback and other baleen whales). As a result, the pattern of decay in basking shark carcasses can be counterintuitive (

figure 5.21). The huge jaws fall off quickly, leaving a surprisingly tiny skull perched at the end of a long spine—looking for all the world like a rotten sea serpent or long-necked plesiosaur. This is what happened to the Stronsay carcass. In the two centuries since the carcass washed ashore, the vertebrae (preserved in museum collections) have been reexamined more than once. Home’s findings have been confirmed each time. In 1933, for example, James Ritchie (then professor of natural history at the University of Aberdeen and later president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh) wrote in the

Times of London about his own conclusions after reexamining the vertebrae of the Stronsay Beast at the Royal Scottish Museum:

They tell their own tale to scientific examination. They are obviously part of the backbone of a gristly fish; by no possibility could they belong to a plesiosaur, or to any reptile or amphibian, nor could they be part of a whale or even of a bony fish. The texture of the segments of the vertebrae, their size, and curious pillared structure, agree exactly with those of the basking shark, a monster which may be 40 ft. long and which occasionally appears in British waters…. The sea-serpent of Stronsay, which a century and a quarter ago raised so great a commotion in the scientific world, has fallen from its unique estate, but it remains a not-to-be-forgotten memorial to the credulity of the inexperienced and of the scientists who built upon so shaky a foundation.

95The Stronsay Beast may never have been quite forgotten (at least within the niche sea serpent literature), but its lesson has never been learned. Again and again, people have fallen for the same grisly illusion. High-profile cases continue to arise, with many “sea serpent” or “plesiosaur” carcasses making headlines during the twentieth century—only to prove, time and again, to be basking sharks. A mere three months after Ritchie confirmed that the Stronsay Beast was really a shark, headlines around the world gleefully announced that a similar unidentified carcass (what is now called a “globster” in cryptozoological parlance) had washed up in Cherbourg, France. The

Los Angeles Times declared it the “First Genuine Sea Monster Captured,” while the front page of the

New York Times trumpeted that “France Has Sea Monster.”

96 After several stories on the topic, the

New York Times made the inevitable retraction: “After a careful examination of the extensive remains of the ‘sea monster’ found on the shore near Cherbourg, Professor [Georges] Petit and his colleagues of the French Museum of Natural History have definitely concluded that this fish is a basking shark.”

97 This was not the last time this clichéd narrative would play out; bizarrely, it was not even the last time it played out in that year. In November 1934, newspapers from Scotland to Chicago trumpeted the discovery of a 30-foot sea serpent carcass on Henry Island (in British Columbia, Canada). The

New York Times got right back on that sea horse, reporting that this “strange sea monster” had a “head resembling that of a horse” and no bones except the vertebrae.

98 Just four days later, the

Times revealed, predictably, that the director of the Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, British Columbia, had positively identified the remains as those of a basking shark.

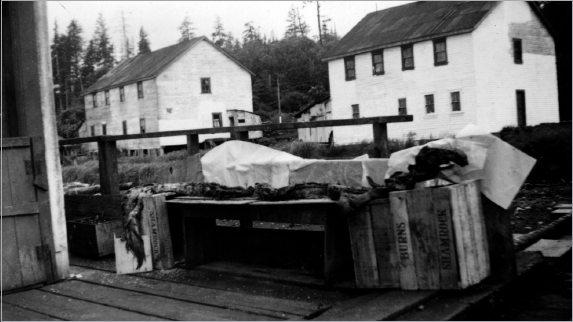

99These misidentifications are among cryptozoology’s silliest banalities, but they are not so passé that they have stopped. The most famous case may be that of the Japanese fishing trawler

Zuiyo Maru, whose crew in 1977 hauled aboard a badly decomposed carcass from the Pacific Ocean off New Zealand (

figure 5.22). Repulsed by the “overpowering stench and the unpleasant fatty liquids oozing onto the deck,” the fishermen photographed the carcass, took tissue samples, and then dumped it overboard.

100 The loss of the specimen did not deter the

Los Angeles Times from excitedly speculating that this reeking, slimy mess could be a relict plesiosaur: “a huge reptile thought to have died out 100 million years ago.”

101 But it was not to be. The tissue samples nailed down what was already obvious to anyone with a sense of history: it was a basking shark.

102 Again.