108 Newby wrote to Lewis on 17 March 1955: ‘We are very glad indeed to learn that the afternoon of Friday 1st April is convenient for you to record a broadcast version of your inaugural lecture…I should be grateful if you could arrive at Broadcasting House at 2.30 p.m…I enclose two copies of the lecture. In one of them I have marked possible cuts, designed more than anything else to remove the lecture from the special Cambridge setting. These are, of course, only my suggestions and you must certainly consider yourself free to accept or reject as you think best…I have today sent off the billing to Radio Times.’

109 Because Lewis rarely saved letters, he would probably have had no record of the address to which he wrote to Kuhn on 6 January 1955.

110 Van Deusen had sent Lewis some stationery with the address of The Kilns printed at the top. He used it in writing this letter.

111 Cf. SBJ, ch. 14, p. 171: ‘All images and sensations, if idolatrously mistaken for Joy itself, soon honestly confessed themselves inadequate. All said, in the last resort, “It is not I. I am only a reminder. Look! Look! What do I remind you of?”’

112 The Apocryphal New Testament: being the Apocryphal Gospels, Acts, Epistles and Apocalypses: with other narratives and fragments, trans. Montague Rhodes James (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924).

113 Dorsett, And God Came In, ch. 4, p. 116.

114 The Farrers had just returned from a holiday in Sicily.

115 ‘Mighty heroes lived before Woolworth’. Lewis, who had in mind the chain store F. W. Woolworth, was making a play on Horace, Odes, book 4, poem 9, line 25: ‘Vixere fortes ante Agamemnona’: ‘Mighty heroes lived before Agamemnon’.

116 i.e. Warnie.

117 A character in Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows (1908).

118 ‘a little force’.

119 Terence, The Woman of Andros act 3, scene 1, line 473: ‘Juno Lucina [Goddess of childbirth], help me.’

120 John Wyndham, The Day of the Triffids (1954).

121 Pierre Barbet, The Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ, trans. from the French by the Earl of Wicklow (Dublin: Clonmore and Reynolds, 1954).

122 Song of Solomon 5:8: ‘I am sick of love.’

123 George Macaulay Trevelyan (1876–1962), historian and Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, 1940–51. See his letter to Lewis of 2 February 1943 (CL II, p. 552).

124 The artist, Fritz Wegner, illustrated Sayers’s pamphlet, The Story of Noah’s Ark, retold by D.L.S. (London: Hamish Hamilton, 12 September 1955). Wegner’s painting for The Story of Noah’s Ark is reproduced in Sayers, Letters, vol. IV, between pp. 204 and 205.

125 Dorothy L. Sayers, The Man Born to be King: A Play-Cycle on the Life of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ (1943).

126 In a letter of 4 April 1955 Sayers asked if she could reprint her essay ‘…And Telling you a Story’ from Essays Presented to Charles Williams. The essay was reprinted in her Further Papers on Dante. See Sayers, Letters, vol. IV, p. 221.

127 Warnie’s ‘The Galleys of France’, first published in Essays Presented to Charles Williams, was reprinted in The Splendid Century.

128 Lewis arranged for all the royalties from Essays Presented to Charles Williams to go to Williams’s widow, Florence ‘Michal’ Williams. See the letter to Florence ‘Michal’ Williams of 13 March 1947 (CL II, pp. 767–8).

129 The reference is to The Twentieth Century, ‘The Cambridge Number’, CLVII, no. 936 (February 1955). In her letter of 4 April 1955 Sayers said: ‘I have just been reading your Inaugural, of which I had previously only heard reports. In particular, there was that “Cambridge” number of The Twentieth Century, which appears to be completely dominated by it, and moreover permeated from end to end by a curious uneasy awareness of Christianity, the like of which I have seldom encountered in so concentrated a form’ (Sayers, Letters, vol. IV, p. 222).

130 See note 99 to the letter to Ruth Pitter of 5 March 1955.

131 Forster, ‘A Letter’, p. 99: ‘How indeed do I define myself? If I say I am an atheist the obvious retort is “That sounds rather crude” if I say I am an agnostic the retort is “That sounds rather feeble” if I say I am a liberal the answer is: “You can’t be; only Socialists and Tories,” and if I say I am a humanist there is apt to be a bored withdrawal. On the whole humanist is the best word, though. It expresses more nearly what I feel about myself, and it is Humanism that has been most precisely threatened during the past ten years.’

132 A seventeenth-century exclamation of derision, remonstrance or surprise. See Thomas Dekker and Thomas Middleton, The Honest Whore (1604, 1630), III, ii, 48: ‘Marry gup, are you grown so holy, so pure, so honest with a pox?’ Lewis uses it in his poem ‘Impenitence’ (reprinted in CP), vii, 1–4: ‘Marry, Gup! Begone, you/Fusty kill-joys, new Manicheans! here’s a/Health to Toad Hall, here’s to the Beaver doing/Sums with the Butcher!’

133 In a footnote to his inaugural lecture, ‘De Descriptione Temporum’, Lewis said of T. S. Eliot’s poem, ‘A Cooking Egg’: ‘In music we have pieces which demand more talent in the performer than in the composer. Why should there not come a period when the art of writing poetry stands lower than the art of reading it?’ (SLE, p. 9). In her letter of 4 April 1955, Sayers commented: ‘I have been greatly bothered by the various “explanations” offered for poems by persons younger and cleverer than myself…I suppose, by the way, that almost the only older poet about whom the same diversity of opinion exists, and has always to some extent existed, is [William] Blake’ (Sayers, Letters, vol. IV, p. 223).

134 A form of light verse dealing with events in polite society.

135 T. S. Eliot, Poems (1920), ‘A Cooking Egg’.

136 Lewis dealt with what he called ‘Privatism’ in Arthurian Torso, ch. 6, p. 188: “‘Privatism”. This occurs when the poet writes what the reader, however sensitive and generally cultivated he may be, could not possibly understand unless the poet chose to tell him something more than he has told. Thus I was informed that I had been wasting my time trying to puzzle out certain lines in a modern poet because the real explanation lay not in the poems but in certain events that had happened while the poet was spending a week-end in my informant’s house. In so far as the poem was addressed to a circle of friends such “privatism” is not a literary fault at all: in so far as the poem was exposed without warning for sale in the shops it seems to me to be simply a way of “obtaining money under false pretences”.’

137 Lewis’s sonnet, ‘Legion’, was published in The Month, XIII (April 1955), p. 210. It is reprinted in Poems and CP.

138 Joy Davidman, Smoke on the Mountain: An Interpretation of the Ten Commandments (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1954); Smoke on the Mountain: An Interpretation of the Ten Commandments in Terms of Today, foreword by C. S. Lewis (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1955).

139 i.e., his new book, Cold War in Hell.

140 On 12 April 1955 Curtis Brown wrote to Gibb about the contract for Surprised by Joy: ‘I sent the contract off to [Lewis] and he has sent it back with a letter saying: “I am afraid…Clause 16 won’t do for–(a) the next, and probably last, of my children’s books must (morally) go first to Lane who have been on this series since Bles died and of whom I have no complaint; (b) I may, any time, produce something for which a university press is the natural publisher”’ (Bodleian Library, Dep. c. 771, fol. 96). Curtis Brown had, perhaps, misunderstood Lewis’s letter: although Geoffrey Bles had retired, he did not die until 1957.

141 ‘truth’ ‘poetry’. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published a succession of volumes entitled Dichtung und Wahrheit (1811–33) in which he recalled the experiences that had most influenced his artistic development.

142 1 Kings 18:28.

143 Jagannath, Lord of the World, is the name given to a particular form of the Hindu god, Vishnu.

144 ‘spiritual discipline’.

145 In Charles Lamb’s story, ‘Mrs. Battle’s Opinions on Whist’, in Essays of Elia (1823).

146 On the industrialization of Oxford by Lord Nuffield see CL II, p. 160n.

147 Bodle said of this letter: ‘The Minister of Education had addressed a group of teachers on the temptations facing the young and said it was the job of the teachers to arm them in the fight. I let off steam in my letter to Lewis and also wrote to the Minister who, I knew, was a Christian. All I got back from the Minister was sympathetic sounds’ (Bodleian Library, MS. Eng. lett. c. 220/4, fol. 249).

148 Frank Percy Wilson was now supervising Fowler’s doctoral dissertation.

149 John Walter Jones (1892–1973) was Tutor in Law at the Queen’s College, Oxford, 1927–48, and Provost, 1948–62. Fowler was a candidate for election as a junior research fellow at The Queen’s College and had in mind an application to Christ Church (‘The House’).

150 i.e. the Long Vacation, which runs from the end of Trinity Term to the start of Michaelmas Term.

151 Laura Philinda (Campbell) Krieg (1917–) was born on 2 September 1917, in Maplewood, New Jersey, the daughter of John Wood Campbell, Sr, an engineer, and Laura (Harrison) Campbell. She was educated at Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, where she completed the first three years. She continued her education informally in Paris, where she lived until 1941. In 1943, she married William Laurence Krieg, an officer of the United States Foreign Service. In 1952, when the family was stationed in Guatemala, Philinda was converted to Christianity by Dr Merrill Hutchins, Minister of Guatemala Union Church. Shortly afterwards she discovered the Narnia books and read them aloud to her son, Laurence, then six years old. He was troubled by his love for Aslan, which he felt was greater than his love for Jesus, and that was the reason she wrote to Lewis. Philinda Krieg is retired and living in Sarasota, Florida.

152 In his ‘Notes on the Letters’ Vanauken stated that he wrote to Lewis about ‘the depth & sharing of the love with Jean, and of their not having children lest the children come between them…and of their long-standing plan to die together. But V had refrained from suicide at her death because of her plea and because of Xtianity. Now, though, V asked, seriously, whether suicide, if done for love and not despair, might be allowed’ (Bodleian Library, MS. Eng. lett. c. 220/2, fol. 152b).

153 Genesis 2:24; Matthew 19:5.

154 For the biography of Rhoda Griggs, see Alice Griggs in the Biographical Appendix to CL II, p. 1050.

155 This letter was first published in The Times (14 May 1955), p. 9, under the title ‘Charles Williams’.

156 Hebrews 6:20; 7:1–28.

157 2 Kings 2:23–4.

158 Genesis 9:20–1.

159 Romans 13:13; Ephesians 5:18; 1 Timothy 3:3.

160 Mark 7:24–30.

161 A review of ‘De Descriptione Temporum’ appeared in Time magazine, 65 (2 May 1955), p. 94, accompanied by a photograph of Lewis by Hans Wild.

162 The Associates of Holy Cross. See the letter to Van Deusen of 26 January 1953.

163 Romans 8:28.

164 Acts 16:3.

165 ibid., 18:18.

166 Thomas Dekker, The Shoemaker’s Holiday (1600), III, v, ‘The Merry Month of May and other songs and ballads’.

167 science fiction.

168 Ernst Robert Curtius, European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, trans. Willard R. Trask (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1953).

169 ‘World’ is one of the words included in Lewis’s Cambridge lectures on ‘Some Difficult Words’, and it is included in Studies in Words (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960; 2nd edn, 1967).

170 i.e., the illustrations for The Last Battle.

171 This was probably the illustration of Aslan standing by the Door in The Last Battle, ch. 14.

172 In a letter of 27 March 1955 Gebbert wrote: ‘Mother and I and the Tycoon spent five days in…Las Vegas…The postcards marked EL RANCHO show where we stayed. They have a large swimming pool, separate bungalows and a wonderful dining room. We were also only a few miles from Yucca Flats where all the Atom bombs are being tested, and on last Tuesday morning, we were awakened by every pane of glass in the windows rattling and being almost shaken out of bed. It felt and sounded like an earthquake (which we know so well)–but it was an A-bomb test!’ (Bodleian Library, MS. Facs. c. 47, fols. 266–7).

173 In her letter of 19 May 1955, Gebbert wrote: ‘I’m reading a wonderful book at the moment, but need your help in some translation. It’s Gerald Bullett’s “The English Mystics.” Have you ever read it? On Chapter 1 of my edition, he says: “All that is positively known of him (John the Scot), apart from his writings, is that he spent some years in France at the court of Charles the Bald, by whom he was appointed head of the schola palatina, and with whom he seems to have been on terms of familiar friendship. The story is told that one day, seated at table with him, the king asked: ‘Quid distat inter sottum et Scottum?’ To which Erigena blandly replied: ‘mensa tantum.’”’ (Bodleian Library, MS. Facs. c. 47, fol. 268).

174 ibid: ‘And on Page 66, we find: “The indefatigable William Land [Laud] (nicknamed parva Laus by Oxford contemporaries)…”’William Laud (1573–1645), Archbishop of Canterbury, 1633–45, was educated at St John’s College, Oxford, and became a Fellow of the College in 1593. He was ordained in 1601 and was made President of St John’s College in 1611. He became a bishop in 1621 and Chancellor of the University of Oxford in 1630. A High Churchman who believed in the Divine Right of Kings, Laud supported King Charles I. He misjudged the Puritans, and despite the fact that he repudiated Catholicism, he was executed in 1645.

175 ibid.: ‘And on Page 128, “In the Divine Dialogues, under the transparent disguise of fiction, he (M Henry More) has recorded a dream-experience of his own: how he was approached by a ‘very grave and venerable person’ who gave him ‘the two keys of Providence, that thou mayest be able to open the treasure of that wisdom thou so anxiously and yet so piously seekest after.’ Each key was found to contain a scroll inscribed with a maxim. The first key, of silver, carried the words: Claude fenestras ut luceat domus. The second, of gold: Amor Dei lux animae.”’

176 Richard Ward, The Life of the Learned and Pious Dr. Henry More, Late Fellow of Christ’s College in Cambridge (1710), p. 56: ‘He was transported…with Wonder, as well as Pleasure, even in the Contemplation of those things that are here below. And he was so enamoured…with the Wisdom of God in the Contrivance of things; that he hath been heard to say, A good man could be sometimes ready, in his own private Reflections, to kiss the very Stones of the Street.’ See the reference to More in CL I, p. 623.

177 In SBJ, ch. 13, the words, ‘Kant’s distinction between the Noumenal and the Phenomenal self’, merged with words on the next page, ‘Bergson showed me.’

178 The title of the book, Surprised by Joy, was taken from the poem by Wordsworth, ‘Surprised by Joy–impatient as the wind’. Lewis quoted the whole line on the title page of the book.

179 In his ‘Notes on the Letters’ Vanauken said: ‘V had written that we are hurried always by time, never able to enjoy any experiences completely because of it’ (Bodleian Library, MS. Eng. lett. c. 220/2, fol. 152b).

180 1 Corinthians 6:16.

181 Romans 6:5.

182 Dante, Paradiso, XXXI, 93.

183 Matthew 6:33.

184 The ‘Five Sonnets’ published in Poems, pp. 125–7, and CP, pp. 139–41.

185 Taprobane is now Sri Lanka.

186 Crim Tartary, a name for the Crimea, is mentioned in William Makepeace Thackeray’s The Rose and the Ring (1855).

187 This was not true.

188 Of a story Fowler was writing.

189 i.e., supernumerary characters.

190 Spencer Curtis Brown had helped Lewis to see that Geoffrey Bles had not given him a fair share of profits from his books. Lewis’s royalties had risen since Curtis Brown Ltd became his literary agent.

191 i.e. George MacDonald: An Anthology.

192 At the beginning of SBJ, ch. 4, Lewis quoted the opening five lines of George Herbert’s ‘The Collar’ from The Temple.

193 Austin Farrer’s article, ‘The Queen of Sciences’, appeared in The Twentieth Century, CLVII, no. 940 (June 1955), pp. 489–94.

194 Henri Estienne, Les Prémices (1594), Bk. 4, epigram 4: ‘Si jeunesse savait; si vieillesse pouvait’: ‘If youth knew; if age could.’

195 Herbert Palmer, The Ride from Hell: A Poem-Sequence of the Times for Three Voices (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1958).

196 St François de Sales , Introduction to the Devout Life, trans. Michael Day (1609; London: Dent, 1961), Part III, ch. 9: ‘On Gentleness towards Ourselves’.

197 Samuel Johnson, Lives of the English Poets, ed. George Birkbeck Hill, 3 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1905), vol. I, ‘Milton’, p. 157.

198 Gibb wrote to Joy Gresham about the corrections, but her reply has not survived.

199 In her letter of 15 June 1955 Gebbert said: ‘You asked about the Tycoon’s mastery of English. Well, wonder of wonders, he put his first sentence together last month. It happened one morning as the two of us were playing in the garden (looking for snails). There was a clicking at the front gate and the Tycoon looked up, glanced at me and shouted “Man with wa-wa!” He was referring to the Monday delivery of bottled water, but how he knew it was the water-man I’ll never know, as he didn’t see him–just heard the clicking of the gate. At any rate, it’s been his first and last sentence in a month, but still and all, a good start, wouldn’t you say?’ (Bodleian Library, MS. Facs. c. 47, fol. 273).

200 ibid.: ‘I would like to find me a quiet planet peopled strictly by INTELLIGENCE (not necessarily human), and where there are no aches or pains or financial worries.’

201 Shakespeare, Hamlet, I, v, 266–7: ‘There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,/Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.’

202 Gebbert said in her letter of 15 June 1955: ‘Our American magazine TIME, in the issue for May 2, 1955, has a fine photo of you and an article about “his recently published inaugural lecture at Cambridge.” Has it been published in this country? If so, I must have a copy for my Lewis shelf. The article in TIME tells us that your subject matter was that “between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance stands history’s Great Divide”’ (Bodleian Library, MS. Facs. c. 47, fol. 273).

203 The Comedy of Dante Alighieri the Florentine, Cantica II: Purgatory <Il Purgatorio>, trans. Dorothy L. Sayers (London: Penguin, 1955). The Comedy of Dante Alighieri the Florentine: Cantica I: Hell <L’Inferno> had been published by Penguin in 1949. Sayers’ translation of Dante was completed by Barbara Reynolds and published as The Comedy of Dante Alighieri the Florentine, Cantica III: Paradise <Il Paradiso>, trans. Dorothy L. Sayers and Barbara Reynolds (1962).

204 Calderon (Pedro Calderón de la Barca) (1600–81), the Spanish dramatist, wrote a number of plays, the best known of which is El Alcalde de Zalamea (c. 1643).

205 The Song of Roland: Done into English, in the Original Measure, by Charles Scott Moncrieff (London: Chapman & Hall, 1919).

206 The High History of the Holy Grail, trans. Sebastian Evans (London: Temple Classics, 1898).

207 i.e., ‘Edmund Spenser, 1552–99’ in Major British Writers, vol. I.

208 William Law, A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1728).

209 The Owl and the Nightingale (c. 1210), 687–8. The words mean that when things have come to the worst they must needs mend.

210 This essay, ‘C. S. Lewis and the Problem of Modern Man’, appeared in Japanese translation in Sophia, 6, no. 1 (Spring 1957), pp. 58–72. Quotations here are taken from the author’s typescript in the Bodleian Library.

211 Milward, ‘C. S. Lewis and the Problem of Modern Man’, p. 1: ‘The name of C. S. Lewis is inextricably associated in the public mind with his masterpiece of human and diabolical psychology, the “Screwtape Letters”…He has himself encouraged this association by undersigning his name on the title-pages of his other books, as “the author of the Screwtape Letters.”’

212 ibid.: ‘The earlier allegory of “The Pilgrim’s Regress”…is an allegorical and universalised account of his own spiritual conversion and shows the gradual development of a modern mind from atheism to Christianity.’

213 ibid., p. 2: ‘We must turn to the series of broadcast talks, which were delivered again during the war years as a means of raising the public morale in England.’

214 ibid.: ‘[His] broadcast talks…have been collected in three small volumes, entitled “The Case for Christianity”, “Christian Behaviour”, and “Beyond Personality.”’

215 ibid.: ‘Together they form an admirably lucid presentation of the Christian ideal of morality and religion.’

216 ibid.: ‘Since the end of the war…we find that he has gradually moved away from the apologetic exposition of Christian teaching as a lay preacher in the modern world, to more literary and scholarly pursuits.’

217 ibid., p. 4: ‘The intrinsic tendency of…experimental science is to focus the attention on material objects, and away from the moral and religious end of Man…The increasing admiration which it fosters for merely human achievements, along with a certain adoration of the power of the human mind, causes inevitably a weakening of the religious instinct.’

218 ibid., p. 9: ‘The most specious of all these ideas…in the eyes of Lewis, is the Philosophy of Science, or Bergson’s theory of Emergence or Creative Evolution…Matter is discovered to possess some mysterious power inherent in itself.’ See the reference to Henri Bergson’s Creative Evolution (1911) in the letter to Owen Barfield of 19 August 1948 (CL II, pp. 870–2).

219 ibid., p. 13: ‘It is significant that in the trilogy of novels Ransom, the hero, is a philologist, and that his friends in “That Hideous Strength” are also philologists, while his opponents are scientists or else the camp-followers of modern science.’

220 ibid., p. 16: ‘The purpose of man on earth…is to be seen against these ultimate issues: to choose the good, which is the way to heaven, and to avoid the evil, which is the road to hell…In pursuing this purpose, a man is following that fundamental instinct of his nature.’

221 ibid., p. 18: ‘If…a man is to achieve his purpose in life, he must not only follow his “sweet desire”, but also strongly act against his selfish desire which would set up self against God…This is what Lewis, in “The Problem of Pain”, terms “the tribulational system”, which is shunned by our human nature, but blessed by God as the divinely appointed means of our redemption.’

222 ibid., p. 19: ‘Thus we are enabled to enter heaven, and so to become more human than we ever succeeded in being on earth, in virtue of our union with Christ, Who alone is perfect Man, fully personal in His human nature, and in Whose nature our imperfect nature is to be perfected.’

223 ‘God forbid!’

224 Milward, ‘C. S. Lewis and the Problem of Modern Man’, p. 19: ‘We realise our collective nature in human society; since union with Christ is not just an affair of the individual, but associates him with his fellow-Christians in the Church.’

225 Martin Buber, Ich und Du (1923), translated as I and Thou by Ronald Gregor Smith (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1937).

226 Cf. the Nicene Creed: ‘We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, eternally begotten of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, of one Being with the Father. Through him all things were made. For us men and for our salvation he came down from heaven: by the power of the Holy Spirit he became incarnate of the Virgin Mary, and was made man. For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate…’

227 The Magician’s Nephew.

228 Of Till We Have Faces.

229 Plautus (254–184 BC), Mostellaria, I, iii, 273: ‘Mulier recte olet, ubi nihil olet’: ‘A woman smells right when nothing smells.’

230 Reviewing The Magician’s Nephew in The Spectator, 195 (8 July 1955), p. 52, Amabel Williams-Ellis said: ‘The present reviewer cannot swallow Aslan, the deus ex machina of all his fairy tales. This personage is a highly moral and decorative lion who not only talks, admonishes and prophesies, but also sings. Surely, Mr. Lewis should, all along, have had the courage of his convictions, and given Aslan the shape as well as the nature and function of an archangel.’

Sayers wrote in a letter, ‘Chronicles of Narnia’, in The Spectator, 195 (22 July 1955), p. 123: ‘May I say…that the Lion Aslan in Professor C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia has most emphatically not the “nature and functions” of an archangel, and for that reason has not been given the form of one? In these tales of the Absolutely Elsewhere, Aslan is shown as creating the worlds (The Magician’s Nephew), slain and risen again for the redemption of sin (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe), incarnate as a Talking Beast among Talking Beasts (passim), and obedient to the laws he has made for his own creation (The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, p. 146). His august Archetype–higher than the angels and “made a little lower” than they–is thus readily identified as the “Lion of the Tribe of Judah.” Apart from a certain disturbance of the natural hierarchies occasioned by the presence in the story of actual human beings, Professor Lewis’s theology and pneumatology are as accurate and logical here as in his other writings. To introduce the historical “form” of the Incarnate into a work of pure fantasy would for various reasons, be unsuitable. Whether, on the other hand, a Talking Beast should be credited with the power of song is a matter for the aesthetics of Fairyland, where cats play the fiddle, horses have the gift of prophecy, and little pigs build houses and boil the pot for dinner. There would seem to be no very valid objection to it.’

231 ‘great translator’. The French poet Eustache Deschamps (1340–1415), a French contemporary of Chaucer, addressed a ballad to the English poet calling him ‘grant translateur’–the medieval French for what would be in modern French ‘grand traducteur’. Lewis has simply given feminine endings: grante translateuse.

232 Kathleen O’Hara.

233 Fairy Hardcastle is the dreadful policewoman in That Hideous Strength. Pitter wrote of this: ‘Mr Sayer & Lewis had asked their way of a neighbour of ours thus attired, who always did remind me of Fairy Hardcastle, though of course we must hope that no human being could come anywhere near that horror’ (Bodleian Library, MS. Eng. lett. c. 220/3, fol. 132).

234 In her note on this letter Pitter said: “‘Eggs of ambivalence” refers to an epigram of mine on Lewis’s going to Cambridge–in his inaugural lecture he referred to himself as a Dinosaur, a rare survival.

Lewis appears, the Trojan Dinosaur,

Eggs of ambivalence distend his Maur.

What meant the Father who convey’d him in?

I wish I knew the mind of those grave Min.

‘The “ambivalence” suggests that under the guise of a harmless Professor…he had been smuggled in to blow some People out of the water. The second rhyme is more respectable than the first. “Min” for “men” is pure Essex, and I am fond of it: in that still half-barbarous county we (the women with grievances) attribute all that goes wrong to The Min–“Blast the Min”!’ (Bodleian Library, MS. Eng. lett. c. 220/3, fols. 132–3).

235 John Earle, Microcosmographie (1628), ‘Of A Patient Man’: ‘He trieth the sea after many shipwrecks, and beats still at that door which he never saw opened.’

236 Louis MacNeice (1907–63), poet and critic, was born in Belfast, but lived in Carrickfergus, 1908–31, where his father was rector of the church. He was educated at Marlborough and Merton College, Oxford. Along with W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Cecil Day-Lewis, MacNeice formed the leading group of poets of the 1930s. His work, which is colloquial and ironic, includes Blind Fireworks (1930), Poems (1935), The Earth Compels (1938), Springboard (1940) and Visitations (1957).

237 Terza rima is the poetic measure adopted by Dante in the Divine Comedy. It consists of lines of five iambic feet with an extra syllable, in sets of three lines, the middle line of each rhyming with the first and third lines of the next set. For instance, the rhyme scheme is aba bcb cdc ded (and so forth) for as long as the poet wishes to continue. Lewis thought MacNeice was abusing it in his Autumn Sequel (1954).

238 Luigi Alamanni (1495–1556), author of La Coltivazione (Paris, 1546) and Opere Toscane (Lyons, 1532).

239 Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503–42), poet, was educated at St John’s College, Cambridge, and held various diplomatic posts with Henry VIII. Because he was closely associated with Anne Boleyn before the King married her, he suffered imprisonment, but not death. Lewis wrote about Wyatt’s poems in English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, Bk. II, ch. 2, pp. 223–30.

240 ‘closer to prose’.

241 Lewis gives an example of Alamanni’s influence on Thomas Wyatt in English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, Bk. II, ch. 2, p. 226.

242 Andrew Marvell, ‘The Definition of Love’ (1681), 1–4: ‘My love is of a birth as rare/As ‘tis for object strange and high:/It was begotten by Despair/Upon Impossibility.’

243 James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson, ed. George Birkbeck Hill, 6 vols. (1934), Saturday 3 April 1773, vol. II, p. 210: ‘Sir, Dr. Goldsmith would no more have asked me to write such a thing as that for him, than he would have asked me to feed him with a spoon, or to do any thing else that denoted his imbecility.’

244 Barbara Reynolds said in Sayers, Letters, vol. IV, p. 252n: ‘Encouraged by…his admiring comment on Introductory Papers on Dante, D.L.S. asked if he would consider writing a preface to her second volume of lectures, Further Papers on Dante, which she was then planning.’

245 In her letter of 8 August 1955, Sayers said: ‘About Pauline Baynes–yes, I did really mean bad drawing–of what is commonly called an “effeminate” kind, because it is boneless and shallow; just the opposite of, say, Blake’s bad drawing, which is lumpy and muscle-bound in a sort of caricature of virility…I can “take” Aslan, though I know some intelligent Christians who can’t–but I cannot “take” (for instance) the frontispiece to The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. It makes me uncomfortable, and if anybody were to call it blasphemous I couldn’t honestly disagree. I rather thought there might be some charitable motive lurking in the background–and that’s fine, so long as it doesn’t do positive harm’ (Sayers, Letters, vol. IV, p. 253).

246 ‘under seal’.

247 Of Farrer’s Gownsman’s Gallows (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1957).

248 ‘prostitute’, lit. ‘girl of joy’.

249 Farrer, Gownsman’s Gallows, ch. 19.

250 Helena Petrovna Hahn Blavatsky (1831–91), Russian-born theosophist who in 1875 founded the Theosophical Society in New York. Her occult books include Iris Unveiled (1877).

251 In a portion of Sayers’ letter of 8 August 1955 not included in Letters, vol. IV, she said: ‘Yes, I know that’s what MacNeice and Co. are doing, but I think they are overdoing it. If you deform a structure beyond a certain point you lose its peculiar virtues without adequate compensation.’

252 Giangiorgio Trissino (1478–1550), Italian poet, who wrote the epic, Sofonisba (1515).

253 See note 245.

254 William Shakespeare, Henry IV Part 1 (1598), I, ii, 119–20: ‘What hole in hell were hot enough for him?’

255 In a letter of 5 August 1955 Gebbert said: ‘Mother and I are trying to sell our home here in Beverly. It’s a costly one to keep up; also, we’re living in the midst of such great wealth. I should dislike the Tycoon trying to “keep up” with the neighboring children; to see and be around such luxury and not being able to have the same. It’s almost unbelievable, but youngsters around here own their own automobiles by the age of 16; are on private yachts week-ends and on European jaunts each summer. I want the Tycoon brought up in simple surroundings with the basic values respected. (Not, mind you, that I’m against week-end yachting and European jaunts–oh no! I would love for the Tycoon to have all that if I were certain he could still retain humility and not let the atmosphere do him harm.) We’re planning on moving far up North–near San Francisco’ (Bodleian Library, MS. Facs. c. 47, fol. 276).

256 This was probably Frank Henry, brother of Vera Henry, who lived near Drogheda. He had a car and used to drive Warnie around during the latter’s holidays in Eire. For his biography, see the letter to Jocelyn Gibb of 15 October 1958.

257 An error for Friday.

258 p.p.

259 Charles Wayne Shumaker (1910–99) was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, on 8 February 1910 and took a BA from Harvard in 1931 and a Ph.D. in 1943. After teaching in a number of colleges, he was Associate Professor and then Professor of English Literature at the University of California, Berkeley, 1946–77. He is the author of The Occult Sciences in the Renaissance (1972) and Unpremeditated Verse: Feeling and Perception in Paradise Lost (1972). He died on 6 March 1999.

260 This letter was first published in The Listener, LIV, no. 1385 (15 September 1955), p. 427, under the title ‘Portrait of W. B. Yeats’.

261 The two meetings are recounted in letters to his brother of 14 March 1921 and to Arthur Greeves of June 1921. See CL I, pp. 530–2, 564–5.

262 St. John Ervine, ‘Portrait of W. B. Yeats’, The Listener, LIV, no. 1383 (1 September 1955), pp. 331–2.

263 See the biography of Father Cyril Charlie Martindale SJ (1879–1963), a friend of Yeats, in CL I, p. 531n.

264 Lewis was referring to his review of The Works of Sir Thomas Malory, ed. Eugène Vinaver (1947), entitled ‘The “Morte Darthur”’ and which appeared in The Times Literary Supplement (7 June 1947). In this review, reprinted in Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature, Lewis said on p. 110: ‘We are not reading the work of an independent artist…Whatever he does Malory’s personal contribution to the total effect cannot be very great, though it may be very good. We should approach the book not as we approach Liverpool Cathedral, but as we approach Wells Cathedral. At Liverpool we see what a particular artist invented. At Wells we see something on which many generations laboured, which no man foresaw or intended as it now is, and which occupies a position half-way between the works of art and those of nature.’

265 In Denis de Rougemont, L’Amour et l’Occident (1939), trans. Montgomery Belgion, published in Great Britain as Passion and Society (London: Faber & Faber, 1940), and in the United States as Love in the Western World (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1940). An augmented edition of Love in the Western World was published by Princeton University Press in 1983 with a 53-page postscript by De Rougemont. On De Rougemont see CL II, p. 379.

266 St Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556), founder of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits).

267 A photo of Lewis by Walter Stoneman which was printed on the cover of Surprised by Joy.

268 Proofs of the American edition of Surprised by Joy, published on 1 February 1956.

269 i.e., the book eventually to be titled Till We Have Faces.

270 George Gilbert Aimé Murray (1866–1957), classical scholar, was born in Sydney, Australia, on 2 January 1866, the son of Sir Terence Aubrey Murray and Agnes (Edwards) Murray. Shortly after his father died in 1873 Gilbert’s mother took him to live in England. He was educated at Merchant Taylors’ School and St John’s College, Oxford, where he took First Class honours in both Classical Moderations (1885) and Literae Humaniores (1888). Murray served as Professor of Greek at Glasgow University, 1889–99, returning to Oxford as Fellow of New College in 1905. He was Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford, 1908–36. His publications include Rise of the Greek Epic (1907), Four Stages of Greek Religion (1912) and Euripides and His Age (1913). He died on 20 May 1957. See Gilbert Murray, An Unfinished Autobiography: with Contributions by his Friends, ed. Jean Smith and Arnold Joseph Toynbee (1960).

271 The period immediately after the First World War when Lewis was going to Murray’s lectures. See CL I, p. 426.

272 ‘good teacher’ ‘good enemy’. Murray was an agnostic.

273 Gilbert Murray, Are Our Pearls Real?, Jubilee Addresses Delivered at the Fiftieth Annual General Meeting of the Classical Association held at University College, London, April 7th to 10th 1957 (London: John Murray, 1954).

274 Gilbert Murray, Religio Grammatici: The religion of a ‘man of letters’ (London: Classical Studies, 1918).

275 The Aeneid of Virgil, trans. C. Day-Lewis (London: Hogarth Press, 1952). The expression does not in fact appear in this translation.

276 The Transformations of Lucius: Otherwise known as The Golden Ass, trans. Robert Graves (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1950).

277 In the preface to William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads, With a Few Other Poems (1798) Wordsworth praised ‘the real language of men’. See CL II, p. 893n.

278 In his Res Gestae, section 1, the Emperor Augustus explained that he had acted ‘res publica ne quid detrimenti caperet’: ‘in order that the republic should not suffer’.

279 Edith Sitwell, Sleeping Beauty (1924).

280 Carl Ferdinand Howard Henry (1913–2004) was born in New York and took his BA from Wheaton College, Wheaton, Illinois, in 1938. After taking a Ph.D. from Boston University in 1949 he taught theology at a number of colleges and seminaries. Henry was the founder of the evangelical periodical, Christianity Today, which he edited, 1956–68. He wrote to ask if Lewis would contribute some articles to Christianity Today.

281 i.e., the ‘book about private prayers for the laity’ mentioned in the letter to Don Giovanni Calabria of 5 January 1953.

282 I. O. Evans, Olympic Runner: A Story of the Great Days of Ancient Greece (London; New York, Hutchinson, 1955).

283 William Golding, The Inheritors (1955).

284 Mrs Janet Wise was living with her husband at The Residency, Mukalla, Hadhramaut (part of the Eastern Aden Protectorate of Arab Sultanates) when she wrote to Lewis. When this letter was published in The Canadian C. S. Lewis Journal, no. 53 (Winter 1986), pp. 1–3, Mrs Wise said of it: ‘I wrote to [Lewis] having been much disturbed by some letters in the Airmail Times…showing the (now widespread) disbelief in the authority of the Bible and, worse still, the Gospels. It appeared that the unforgivable sin to these clerics was to be a FUNDAMENTALIST! I regarded myself, and still do, as an intelligent Fundamentalist and wished to have some list of modern books on theology to try to find out how on earth they came to their disbeliefs. I had plenty of time in those days–and needed only a list and a bookseller to write to. You may be interested in the letter [Lewis] wrote me–as usual, courteous, painstaking and immensely interesting.’

285 In 1 Samuel 16–1 Kings 2; 1 Chronicles 2–29.

286 John Calvin, Sermons on the Book of Job (1574), ‘Second Sermon on First Chapter of Job’.

287 i.e. the headmaster of Malvern College, Donald Lindsay.

288 This is the only known reference to Lewis having been threatened by a possible cancer.

289 In the Book of Common Prayer. One of the supplications in the Litany is: ‘By thine Agony and bloody Sweat; by thy Cross and Passion; by thy precious Death and Burial; by thy glorious Resurrection and Ascension; and by the coming of the Holy Ghost–Good Lord, deliver us.’

290 See Barbara Reynolds in the Biographical Appendix.

291 In ‘Memories of C. S. Lewis in Cambridge’, The Chesterton Review, XVII, nos. 3, 4 (August/November 1991), p. 381, Reynolds recalled the evening when Lewis came to a discussion at her house in Cambridge: ‘The subject that evening was “Dante and the English Reader.” It was an informal occasion, just a few friends gathered round the fire in my book-lined sitting-room. The Professor of Italian, E. R. Vincent, was present. So too was another of my colleagues, Father Kenelm Foster, o.p., a specialist in Dante studies. As I later wrote to Dorothy Sayers, “Lewis contributed a great deal of wisdom and bonhomie.” I remember that he considered that Italians tended to misunderstand Dante. The reason for this, he suggested, was that Dante’s language is nearer in meaning and association to mediaeval Latin than to modern Italian, “but of course you’d never get an Italian to agree.” He suggested that a veil of classicism had descended in the intervening centuries which blurred the impact of Dante’s poetry for modern Italian readers.’

292 A mistake for November.

293 ‘Dante’s Statius’, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature, p. 101.

294 ibid., pp. 101–2.

295 The correspondence with Dunbar is treated at length in Dr Andrew Cuneo’s unpublished doctoral thesis, ‘Selected Literary Letters of C. S. Lewis’ (2001) (Bodleian Library: MS. D.Phil. c. 16354).

296 See Nan Dunbar in the Biographical Appendix.

297 The passage Lewis and Dunbar were concerned with in Statius, Thebaid, II, 230–235, reads as follows: ‘ibant insignes vultuque habituque verendo/candida purpureum fusae super ora pudorem/deiectaeque genas; tacite subit ille supremus/virginitatis amor, primaeque modestia culpae/confundit vultus; tunc ora rigantur honestis/imbribus, et teneros lacrimae iuvere parentes’: ‘Distinguished, they went, with their expression and clothing showing due reverence, with red-tinged modesty (pudorem) covering over their fair faces, the eyes cast down; that last love of their maidenhood insinuates itself quietly, and their modesty at this initial offence (culpae) spreads over their features; then their faces are wet with an honoured torrent, and these tears delight their tender parents.’

298 Ovid, Metamorphoses, Bk. I, 478.

299 ibid., Bk. I, 483. The complete line reads: ‘illa velut crimen taedas exosa iugales’: ‘She [Daphne], hating the wedding torches, as if they were a matter for reproach.’

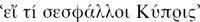

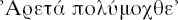

300 Euripides, Andromache, 223. The full phrase is:  : ‘If Cypris (Aphrodite) ever tripped you in any way…’

: ‘If Cypris (Aphrodite) ever tripped you in any way…’

301 Virgil, Aeneid, IV, 15–17: ‘si mihi non animo fixum immotumque sederet/ne cui me vinclo vellem sociare iugali,/postquam primus amor deceptam morte fefellit…’: ‘If this were not planted fixed and immoveable in my mind: that I should not want to ally myself to anyone in a conjugal bond, after my first love proved vain to me, cheated by death…’

302 ibid., 172: ‘coniugium vocat, hoc praetexit nomine culpam’: ‘Marriage she calls it; by that name she covers over her offence.’

303 Statius, Thebaid, II, 255. The full passage, starting at the end of line 253, is as follows: ‘hic more parentum/Iasides, thalamis ubi casta adolesceret aetas,/virgineas libare comas primosque solebant/excusare toros’: ‘Here, following the custom of their parents, the daughters of Iasus, when the age of innocence had progressed to the age for marriage, were accustomed to dedicate their locks of their hair as maidens and ask to be excused from (excusare) a first marriage.’ Dunbar would probably prefer that the meaning of excusare would be something as follows: ‘…and make excuses [to Minerva] for the first marriage’.

304 i.e., Pallas Athena or Minerva.

305 Statius, Thebaid, VIII, 625–8: ‘ecce ego, thalamus, nec si pax alta maneret,/tractarem sensu–pudet heu!–conubia vidi/nocte, soror; sponsum unde mihi sopor attulit amens/vix notum visu?’ ‘Behold! I who should not be dealing with marriage, even if a deep peace persisted–for shame alas!–I saw nuptials (conubia) in the night, sister: from where did demented sleep carry to me my betrothed (sponsum) barely known by sight?’

306 ibid., 645: ‘…tenuit saevus pudor’: ‘fierce shame held her’.

307 Dunbar would not budge from her position. She wrote by return of post challenging the three examples Lewis had used to support Statius’s views. According to Cuneo, ‘Selected Literary Letters of C. S. Lewis’, p. 81: ‘In example one, she considered a feeling of culpa to be a standard reaction of a female Greek about to be married, not a development in ethical sensibility. In example two, excusare refers to a ritual act expected of brides who wished to excuse themselves to a goddess of virginity. Lastly, in example three, Ismene relates her dream, according to Dunbar, because she is ashamed of its sexual content; this explains the violent reaction of Atys’s mother.’

308 i.e., locus communis: ‘commonplace’.

309 Statius, Thebaid, II, 256.

310 ibid., VIII, 626.

311 ibid.

312 A Latin Dictionary Founded on Andrews’ edition of Freund’s Latin Dictionary, rev. and enlarged edn by C. T. Lewis and C. Short (1879).

313 Statius, Thebaid, VIII, 627.

314 Euripides, Electra, 481: lit. ‘bed’ or ‘marriage-bed’.

315 ‘from where’, referring to Statius, Thebaid 8.627, i.e. to Statius, Thebaid, VIII, 627.

316 Lavinia is the daughter of Latinus, king of the Latini. She subsequently becomes wife to Aeneas.

317 Alan E. Boucher, Programme Assistant, School Broadcasting Department of the BBC, wrote to Lewis on 17 October 1955: ‘I wonder whether you would consider giving a twenty minute talk for Sixth Forms…under the heading “The Christian Writer in the Modern World”.’

318 ‘On Science Fiction’, read to the Cambridge University English Club on 24 November 1955, and published in Of This and Other Worlds.

319 In ‘Selected Literary Letters of C. S. Lewis’, p. 83, Cuneo explained that Dunbar, unsatisfied with Lewis’s letter of 17 October 1955, ‘writes back immediately, trying to press her point about the meaning of culpa one last time. She senses his concern that conubia might well mean marriage, not spouse, for spouse is accounted for by sponsum. Why would Statius repeat himself, she asked Lewis? The words refer to two different nouns. Nevertheless, she admits that Virgil uses a word for marriage, conjugium, to mean spouse–and several times (cf. Aeneid 7:423, 433 and 11:270). Dunbar concludes by emphasizing how Ismene’s shame over the dream can best be connected to the belief that the dream was of sexual union; after all the verb attulit indicates that Atys was in very close proximity to Ismene.’

320 Statius, Thebaid, II, 233.

321 ibid., VIII, 626.

322 Homer, Odyssey, VI, 66.

323 ibid.: ‘She was ashamed to speak (of marriage)’.

324 Virgil, Aeneid, III, 1–3: ‘Postquam res Asiae Priamique evertere gentem/immeritam visum superis, ceciditque superbum/Ilium et omnis humo fumat Neptunia Troia…’: ‘After it seemed best to the gods to overturn the kingdoms of Asia and the undeserving race of Priam, and proud Ilium fell, and all of Neptune’s Troy lay smouldering on the ground…’

325 Statius, Thebaid, VIII, 627.

326 ‘the act of love’.

327 ‘special pleading’.

328 i.e. Lewis and Short, Latin Dictionary.

329 ‘you have won’: the dying words of Julian the Apostate addressed to ‘The Galilean’.

330 Laurence John Krieg (1945–) was born in Caracas, Venezuela on 11 December 1945, the first of three children of William Laurence Krieg and Laura Philinda (Campbell) Krieg. His father was a member of the United States Foreign Service, and the family moved from Caracas in 1946 to Bethesda, Maryland, in 1948, and to Guatemala in 1951. They returned to Bethesda in 1954, moving to Chile in 1958, where Laurence attended the Grange School. After the Krieg family returned again to Bethesda in 1961 he attended high school, graduating in 1964. He took his BA in 1968 from the College of Wooster, Wooster, Ohio. Inducted into the army the same year, in 1969 he served in Vietnam. On his discharge in 1970 he entered the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor where he specialized in linguistics, taking a MA in 1974 and a Ph.D. in 1980. He took a job with Computer Sciences, Inc., in 1981, before moving to MDSI Manufacturing Data Systems, Inc., and joined the faculty of Washtenaw Community College, Ann Arbor, in 1983. In 2000 he became chairman of Internet Professional Department. Despite the technical turn of his career, he still considers Lewis his mentor and guide.

331 Lewis was confused. Rabadash fights the panthers in The Horse and His Boy, ch. 13.

332 James 1:20.

333 There had been much speculation in the media as to whether Princess Margaret, the sister of Queen Elizabeth II, would marry divorced Group Captain Peter Townsend. On 31 October 1955 the Princess announced that she would not marry him.

334 Cuneo, ‘Selected Literary Letters of C. S. Lewis’, p. 85.

335 Dunbar had written to Lewis to say she had found a word in Justin Martyr, the Apologist (c. AD 100–65) referring to a point in his lecture.

336 Lewis had earlier put these words into Screwtape’s mouth in The Screwtape Letters, Letter 21, p. 81: ‘Men are not angered by mere misfortune but by misfortune conceived as injury.’ He was unable to find these words in the works of Hobbes.

337 The Oxford English Dictionary gives ‘Injury, as distinct from harm, may raise sudden anger’ from Bishop Joseph Butler’s Analogy of Religion (1736). Dunbar attempted to find a similar specimen from Hobbes and her searches may have resulted in what appears of Hobbes in Studies in Words.

338 Lewis was referring to his conversation with Greeves in September about the possibility of marrying Joy Gresham at a register office.

339 On the Waverley novels of Sir Walter Scott see CL II, p. 898n.

340 1 Corinthians 15:47.

341 Psalm 116:7.

342 Gebbert, her son, and her mother had now moved to Carmel, California, and they gave their address as Box 3966, Carmel, California, USA.

343 Shelburne’s review of Surprised by Joy.

344 St François de Sales, Introduction to the Devout Life (1619), Part III, ch. 10, ‘Avoidance of Over-Eagerness and Anxiety’, p. 110: ‘It is one thing to manage our affairs with care, another to do so with worry, over-eagerness and anxiety. The angels take care of our salvation with diligence yet without any worry, anxiety or over-eagerness, for care and diligence accord with their charity while worry, anxiety and over-eagerness would not accord with their happiness; since care and diligence may be accompanied by peace and tranquillity but not worry, anxiety and even less over-eagerness. Carry out all your duties…with care and diligence, for this is God’s will, but as far as possible avoid being worried or anxious about them…All eagerness disturbs our judgement, and hinders us from doing well the work we are eager to do.’

345 See Sayers’s review of Surprised by Joy in Time and Tide, 36 (1 October 1955), pp. 1263–4.

346 In 1967 Banner and his wife Josefina de Vasconcellos (1904–2005), through associations with Pelham House Approved School in West Cumbria, helped found Outpost Emmaus, an centre offering outdoor activities for disadvantaged boys at Beckstones in the Duddon valley.

347 Banner had done a drawing of (Sir) Christopher John Chataway (1931–), champion athlete, and later a television news broadcaster and Conservative politician. Chataway was educated at Sherborne School and went up to Magdalen College, Oxford, in 1950. His studies in Politics, Philosophy and Economics were overshadowed by his success as a long-distance runner. In the Helsinki Olympics of 1952, he took fifth place in the 5,000 metres, and gained second place in the same event at the 1954 European Athletics Championship. Two weeks later he set a world record time of 13 minutes 51.6 seconds in the event. Chataway took his BA in 1954, and in 1955 became a newscaster for Independent Television News. He worked for the current affairs department of BBC TV, 1956–9. Long interested in politics, he was elected as a Conservative to the London County Council in 1958. When the Conservatives were defeated in 1974 he went into business, becoming managing director of Orion Bank and a director of British Electrical Traction Ltd. He was knighted in 1995.

348 H. C. Chang, Allegory and Courtesy in Spenser: A Chinese View (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1955).

349 ‘daemon’.

350 The equivalent of Oxford’s Senior Common Room, the room in which dons have informal meals.

351 Chad Walsh, Behold the Glory (New York: Harper, 1956). See the letter to Walsh of 28 February 1956.

352 i.e. God’s plan for the Catholic Church. God is named ‘The Landlord’ in The Pilgrim’s Regress.

353 Of Surprised by Joy.

354 George Eliot, The Mill on the Floss (1860); Adam Bede (1859).

355 Dunbar was delighted that literature, and not just antiquity, had become part of her conversation with Lewis. According to Cuneo, ‘Selected Literary Letters of C. S. Lewis’, p. 87, ‘After dipping into Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae and finding “all sorts of splendid things”, she expressed her regret to him that there was no more time to read such books.’

356 Horace, Epistles, I, xiv, 43: ‘Optat ephippia bos piger, optat arare caballus’: ‘The lazy ox wishes for horse-trappings, and the steed wishes to plough.’

357 Jean Froissart (c. 1337–c. 1410), French chronicler and poet, whose Chronicles Lewis wrote about in English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, pp. 153–6.

358 Snorri Sturluson (1178–1241), Icelandic historian. See English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, p. 117.

359 Jean de Joinville (c. 1224–1317), the author of the Chronicle of St Louis, is mentioned in The Discarded Image, ch. 7, pp. 177–8.

360 See Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie (1532–92) in English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, pp. 117–18.

361 Lewis was referring to Gavin Douglas (1475–1522), best known for his Scots translation of the Aeneid which was entitled the XIII Bukes of the Eneados (1553). Dunbar told Lewis she would read it in the Christmas vacation, and she did.

362 See Muriel Bradbrook, Cambridge lecturer in English Literature, in the Biographical Appendix.

363 Gibb was planning a third edition of The Abolition of Man.

364 On 8 December 1955 Gibb wrote to Lewis: ‘We have had a letter from your German publisher, Jacob Hegner, who is anxious to do an omnibus volume of your children’s stories, unillustrated. I have a sort of idea you may not be very keen on that…“Irish Digest” have asked us if we will permit them to print a condensed portion of Surprised by Joy in one of their issues’ (Bodleian Library, Dep. c. 771, fol. 126).

365 Those Inklings who had met her thought Pauline Baynes very beautiful.

366 A reference to Genesis 9:20–3: ‘Noah began to be an husbandman, and he planted a vineyard: And he drank of the wine, and was drunken; and he was uncovered within his tent. And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without. And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward, and covered the nakedness of their father: and their faces were backward, and they saw not their father’s nakedness.’ The Sin of Ham is traditionally understood to be the fact that Ham did not cover his father’s nakedness.

The passage published in The Irish Digest, LV, no. 3 (January 1956) was entitled ‘My Father’s Eloquent Mistake’. It consisted of the last few pages of SBJ, ch. 2, beginning with the paragraph that opened: ‘In attempting to give an account of our home life…’

367 Blamires’s trilogy consisted of The Devil’s Hunting-grounds, Cold War in Hell, and most recently Blessing Unbounded: A Vision (London: Longmans, 1955).

Michael Longman, the publisher, had appealed to Lewis for help in advertising Blessing Unbounded, saying in a letter to Blamires of 9 December 1955: ‘We…plan to advertise in the Church Times, using, with permission, what C. S. Lewis kindly wrote about the book when I sent him a copy. He thought this last one is definitely the best of the three and he admires “the way in which he leads us time after time up the garden path; each time you think you’re in for a well-worn type of ridicule directed against a too-familiar target, and each time you find that the purpose is quite different.” He also says “The landscape is well done too and very economically. Annot was a dangerous figure to introduce, but I think he has succeeded. So, I hope, will the book” and he asks me to pass on his cordial good wishes. Incidentally he remarked that he thought that any opinion of his about the book, which we quoted in the advertisement, would put off as many people as it might attract, but I think in the present circumstances (even if it is true) that risk is justified’ (letter in possession of Harry Blamires).

368 The Wanderer, 50, ‘sorrow is renewed’ (when the exile wakes after dreaming of home).

369 Sir Philip Sidney, The Countess of Pembrokes Arcadia (1590) Bk. III, Ch. 27: ‘Hope is the fawning traitor of the minde.’,

370 Continuing their correspondence about fantasy and imagination, Sayers said in a letter of 21 December 1955: ‘I think the trouble is that the unscrupulous old ruffian inside one who does the actual writing doesn’t care tuppence where he gets his raw material from. Fantasy, memory, observation, odds and ends of reading, and sheer inventions are all grist to his mill, and he mixes everything up together regardless. The critics can’t sort it out…so they just explain it all by “fantasy”, and make up imaginary biography to explain the bits they can’t account for’ (Sayers, Letters, vol. IV, p. 260).

371 J. R. R. Tolkien, ‘On Fairy-Stories’ in Essays Presented to Charles Williams.

372 Anthony Trollope, An Autobiography (1883).

373 ‘as such’.

374 ‘man the toolmaker’. The phrase comes from Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution.

375 Sayers asked in her letter of 21 December 1955: ‘Is the Imagination (in our sense) going to become, eventually, the exclusive appanage of those who study Humanities? I hear disquieting reports from the new towns and the dormitory suburbs’ (Sayers, Letters, vol. IV, p. 262).

376 Émile Coué (1857–1926), a French doctor who popularized a system of psychotherapy based on autosuggestion.

377 Prisoner of war.

378 Matthew 25:34–46.

379 Romans 8:2–4: ‘For the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus hath made me free from the law of sin and death. For what the law could not do, in that it was weak through the flesh, God sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh, and for sin, condemned sin in the flesh; that the righteousness of the law might be fulfilled in us, who walk not after the flesh, but after the Spirit.’

380 St Augustine, Homilies on the First Epistle of John, Homily VII, Section 8: ‘dilige et quod vis fac’.

381 Psalm 36:11: ‘O let not the foot of pride come against me: and let not the hand of the ungodly cast me down.’

382 Psalms 36:8: ‘They shall be satisfied with the plentousness of thy house: and thou shalt give them drink of thy pleasures, as out of the river.’

383 i.e., the Blessed Virgin Mary.

384 ‘in my opinion’.

385 ‘a refuge for ignorance’.

386 Wisdom of Solomon, 16:20: ‘Instead of these things you gave your people food of angels, and without their toil you supplied them from heaven with bread ready to eat, providing every pleasure and suited to every taste.’

387 Ronald Knox, Enthusiasm (1950).

388 Rougemont, L’Amour et l’Occident, Book VII, ch. 5: ‘Love ceases to be a demon only when he ceases to be a god.’

389 St Ignatius of Loyola was a handsome young knight who loved romances of chivalry. He was badly wounded in battle and, while recovering, the only thing he could find to read were the lives of the saints. He began to see their lives as chivalric, and it brought him joy and peace. His conversion reached its climax when, as he said in his autobiography, he saw ‘an image of Our Lady with the Holy Child Jesus’.

390 Amadis of Gaul is a Spanish or Portuguese romance that has come down to us in the form given it by Garcia de Montalvo in the second half of the fifteenth century, and printed early in the sixteenth century.

391 In Evelyn Underhill’s The Golden Sequence (1933), Gebbert had come across the words of the ‘Veni, Sancte Spiritus’, or ‘Golden Sequence’. This is the sequence for the Mass for Pentecost, and is regarded as one of the greatest masterpieces of sacred Latin poetry. It is not known who wrote it, but it is commonly thought it was the work of Stephen Langton (d. 1228), Archbishop of Canterbury. It consists of thirty-one lines, those Gebbert asked Lewis to translate being: ‘Sine tuo numine/nihil est in homine/nihil est innoxium’ which is translated in the Catholic Missal in the Mass for Pentecost: ‘Where you are not, man has naught,/Nothing good in deed or thought,/Nothing free from taint of ill.’

392 Deuteronomy 33:27.

393 Lewis was referring to the literary critic, Sir William Empson (1906–84), whose The Structure of Complex Words (1951) is his tour de force on how attentiveness to double meanings can enrich our appreciation of literature and language.

394 It is not known how Sayers described them.

395 Gundreda Forrest (1888–1978), Lewis’s cousin, was the daughter of Sir William Quartus Ewart (1844–1919) and Lady Ewart (1849–1929) who lived at Glenmachan, Strandtown. They were described in SBJ, ch. 3, as ‘Cousin Quartus’ and ‘Cousin Mary’, and Gundreda Ewart as ‘the most beautiful woman I have ever seen’. See The Ewart Family in the Biographical Appendix to CL I, pp. 990–2.

396 ‘Mountbracken’ is the name given the Ewart family home, Glenmachan, in SBJ, ch. 3.

397 Lewis described Gundreda’s sister, Kelso ‘Kelsie’ Ewart (1888–1966) as follows: ‘K. was more like a Valkyrie…with her father’s profile. There was in her face something of the delicate fierceness of a thoroughbred horse’ (ibid.). Kelsie never married and lived near Glenmachan all her life.

398 Shakespeare, Hamlet, I, ii, 187: ‘I shall not look upon his like again.’ Samuel Graham was the Ewart family coachman and Palmer the family butler. Warnie Lewis described both of them in LP III: 258.

399 William Adrian John Forrest (1929–) and Rachel Primrose Forrest (1928–) are the children of Gundreda and her husband John Vincent Forrest (1873–1953). In 1949 Primrose Forrest married Oscar William James Henderson, formerly of the Irish Guards.

1 Jill Freud’s dog.

2 See Muriel Bradbrook in the Biographical Appendix.

3 Bradbrook had invited Lewis to Girton College to meet Nan Dunbar.

4 Thomas Malory, Le Morte Darthur, Bx. XIX, Ch. 8: ‘Unless I’m sick or in prison.’

5 While this letter is in Lewis’s hand, the reference number was added by Warnie.

6 In his reply of 26 January 1956, Gibb said: ‘I am sorry to say it is too late to make either of these corrections in the second printing but we have placed them ready for the third’ (Bodleian Library, Dep. c. 771, fol. 129). The first of these errors was corrected in the third impression of the book, and in SBJ, ch. 14, p. 166 the passage reads: ‘George Herbert…was a man who seemed to me to excel all the authors I had ever read in conveying the very quality of life as we actually live it from moment to moment; but the wretched fellow, instead of doing it all directly, insisted on mediating it through what I would still have called “the Christian mythology”.’ The second error occurred in ch. 15, and the sentence in question read: ‘I was by now too experienced in literary criticism to regard the Gospels as myths…And yet the very matter which they set down in their artless, historical fashion–those narrow, unattractive Jews, too blind to the mythical wealth of the Pagan world around them–was precisely the matter of the great myths.’ This has never been corrected to ‘so blind’ in either the English or the American editions of the book.

7 Henrik Ibsen, Peer Gynt (1867).

8 Old English.

9 William Langland (c. 1330–c. 1386), Piers Plowman.

10 Behold the Glory. See the letter to Chad Walsh of 3 December 1955.

11 Cuneo, ‘Selected Literary Letters of C. S. Lewis’, p. 89.

12 ibid.

13 Lewis refers here to the first half of Aristotle’s poem, ‘Ode to Arete’, quoted by Diogenes Laertius (first half of the third century AD) in his life of that philosopher. The following translation is from Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, trans. R. D. Hicks (London; New York: Heinemann, Putnam, 1925), vol. 1, p. 451: ‘O Virtue, toilsome for the generation of mortals to achieve, the fairest prize that life can win, for thy beauty, O virgin, it were a doom glorious in Hellas even to die and to endure fierce, untiring labours. Such courage dost thou implant in the mind, imperishable, better than gold, dearer than parents or soft-eyed sleep. For thy sake Heracles, son of Zeus, and the sons of Leda endured much in the tasks whereby they pursued thy might. And yearning after thee came Achilles and Ajax to the house of Hades, and for the sake of thy dear form the nursling of Atarneus too was bereft of the light of the sun. Therefore shall his deeds be sung, and the Muses, and the daughters of Memory, shall make him immortal, exalting the majesty of Zeus, guardian of strangers, and the grace of lasting strangers.’ The ‘nursling of Atarneus’ is Hermias, tyrant of Atarneus, in whose honour the poem was written, said to have given in marriage to Aristotle either a daughter or a niece.

Shortly afterwards Lewis published a translation of the ‘Ode to Arete’ as ‘After Aristotle: in The Oxford Magazine, LXXIV (23 February 1956), p. 296. It is reprinted in CP.

in The Oxford Magazine, LXXIV (23 February 1956), p. 296. It is reprinted in CP.

14 Presumably the Greek playwright Menander (344/3–292/1 BC). If so the reference is odd since, as a comic writer, one would not normally have thought him emblematic of the best that Greece had to offer by way of poetry. The praise of Aristotle’s poem may also be said to be over-florid, but Lewis’s translation suggests that he valued the poet highly.

15 Translation by Nan Dunbar from Cuneo, ‘Selected Literary Letters of C. S. Lewis’, p. 89.

16 In a letter of 26 January 1956 Gibb said: ‘I enclose copies of the Swedish edition of The Problem of Pain and the German edition of The Great Divorce. Doesn’t “Die Grosse Scheidung” sound much better than the English title? I wonder what you will think of its illustrations: Herr Seewald certainly has ideas’ (Bodleian Library, Dep. c. 771, fol. 129). The Swedish edition of The Problem of Pain was called Lidandets Problem, trans. Aslög Davidson (Lund: Gleerup, 1955). The German edition of The Great Divorce was Die Grosse Scheidung, oder Zwischen Himmel und Hölle [The Great Divorce, or: Between Heaven and Hell], trans. Helmut Kuhn, with illustrations by Richard Seewald (Köln: Hegner, 1955).

Lewis and Gibb admired Seewald’s illustrations to Die Grosse Scheidung because of his ability to convey so much with a few simple lines. Besides this, he fulfilled Lewis’s desire to make everything in heaven real and solid and the damned blurred and indistinct. To illustrate ch. 8, in which a female Ghost tries to hide from two of the Solid People, two naked males are portrayed as massive, solid and radiant, while the landscape is seen through the body of the naked Ghost.

17 Krieg wrote this letter from 5208 Glenwood Road, Bethesda, Maryland.