C. S. Lewis’s ‘Great War’ with Owen Barfield, named after the conflict in which each had taken part between 1914 and 1918, arose from Lewis’s efforts to dissuade Barfield from belief in anthroposophy. This is a system of theosophy evolved by Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925) and based on the premise that the human soul can, of its own power, contact the spiritual world. Central to it are the concepts of reincarnation and karma. While it acknowledges Christ as a cosmic being, its understanding is not that of orthodox Christianity. It was condemned by the Catholic Church, along with other forms of Theosophy, on 7 July 1919.1

Having served in the First World War, Lewis, Barfield and Cecil Harwood arrived in Oxford in 1919. Barfield and Harwood had been at Highgate School together, and were already friends. Barfield matriculated at Wadham College and Harwood at Christ Church. In 1919 they met Lewis, a Scholar of University College, after which the three men were to see a great deal of one another. Lewis took Firsts in Classical Honour Moderations and Literae Humaniores in 1920 and 1922, and during 1922–3 he read the course in English Language and Literature. Barfield took a First in English Language and Literature in 1921 and remained in Oxford to prepare for his B. Litt. thesis on ‘Poetic Diction’. After taking a First in History in 1921 Harwood took a temporary job in London with the British Empire Exhibition. It was during Harwood’s weekend visit to Oxford in July 1923 that anthroposophy is first mentioned in Lewis’s writings. In his diary of 7 July 1923 he records that

Harwood…told me of his new philosopher, Rudolf Steiner, who has ‘made the burden roll from his back’. Steiner seems to be a sort of panpsychist, with a vein of posing superstition, and I was very much disappointed to hear that both Harwood and Barfield were impressed by him…I argued that the ‘spiritual forces’ which Steiner found everywhere were either shamelessly mythological people or else no-one-knows-what. Harwood said this was nonsense and that he understood perfectly what he meant by a spiritual force. I also protested that Pagan animism was an anthropomorphic failure of imagination and that we should prefer a knowledge of the real unhuman life which is in the trees etc.2

Lewis had rejected Christianity some dozen years before, and after he began reading Philosophy at Oxford he came to believe in Idealism. Barfield and Harwood shared with Lewis this belief in the primacy of spiritual reality, which was essentially one of divine immanence rather than transcendence. Idealism reached the common man in the form of a diffused and vague pantheism. Lewis did not understand enough of Christianity to argue with Barfield and Harwood about the heretical qualities of Anthroposophy. He was nevertheless ‘hideously shocked’3 and felt ‘deserted’4 when they became Anthroposophists in 1923. Both met Steiner when he visited England in August 1924. As Lewis wrote in Surprised by Joy,

Barfield’s conversion to Anthroposophy marked the beginning of what I can only describe as the Great War between him and me. It was never, thank God, a quarrel, though it could have become one in a moment if he had used to me anything like the violence I allowed myself to him. But it was an almost incessant disputation, sometimes by letter and sometimes face to face, which lasted for years. And this Great War was one of the turning points of my life.5

It is impossible to be certain, but the ‘Great War’ letters were probably written in 1927 and 1928. Lewis took up his appointment as Fellow of English at Magdalen College in 1925, and Barfield, who had married in 1923, moved to London that same year to work on the magazine Truth and to further his literary career. In 1929 Barfield’s father lost the services of a brother in their London law firm of Barfield and Barfield, and Owen joined the firm in order to help. Even so, between 1923 and 1929 he had six productive years. Apart from his work with Truth, he produced a fairy tale of the Hans Andersen kind, The Silver Trumpet (1925) and a work on the changes in the meaning of words over time, History in English Words (1926), as well as revising his B. Litt. thesis, Poetic Diction: A Study in Meaning, which was published in 1928.

The ‘Great War’ letters that have survived were written between 1927 and 1928. Originally each man wrote about a dozen letters, but the only ones to survive are ten from Lewis and two from Barfield. All were all preserved by Barfield, who saved most of the letters he received from Lewis. The two letters from Barfield are drafts of those he sent to Lewis: the first is dated 28 July 1927, and the second, which is undated, opens with the words: ‘I begin with a few detailed comments.’ For the sake of convenience they will be referred to as First Letter and Second Letter.

It should be remembered that during this period the Great War was not confined to letter-writing. Lewis and Barfield talked about these matters when they saw one another. Even more important in understanding the letters is Barfield’s Poetic Diction: A Study in Meaning. Barfield and Lewis had been discussing the manuscript of this thesis for years, but unfortunately Lewis’s notes on it have been lost. What he principally took exception to was Barfield’s view of imagination as a vehicle of truth. This is one of the main contentions in Series I of the ‘Great War’ letters. Barfield wrote:

Seeking for material in which to incarnate its last inspiration, imagination seizes on a suitable word or phrase, uses it as a metaphor, and so creates a meaning. The progress is from Meaning, through inspiration to imagination, and from imagination, through metaphor, to meaning; inspiration grasping the hitherto unapprehended, and imagination relating it to the already known.6

In the letters grouped in Series II Lewis turns from the subjects they have been discussing to warn his friend against Anthroposophy. It is Anthroposophy which is the principal subject of the rest of the Great War documents. They are: (1) Lewis’s two-part tractate, Clivi Hamiltonis Summae Metaphysices contra Anthroposophos (November 1928), better known as the ‘Summa’, after St Thomas Aquinas’ Summa contra Gentiles –‘Clive Hamilton’ was Lewis’s pseudonym;7 (2) Replicit and Autem (1929)–‘Reply’ and ‘Further Observations’–by Barfield; (3) Replies to Objections and Note on the Law of Contradiction (1929) by Lewis; (4) De Bono et Malo (1930)–‘Of Good and Bad’–by Lewis; (5) De Toto et Parte (1930?)–‘Of the Whole and the Part’–by Barfield; and (6) the unfinished Commentarium in De Toto et Parte –‘Commentary on ‘Of the Whole and the Part’–by Lewis (1931?). As we know, Lewis was converted to Christianity on 19 September 1931, and this marked the end of the ‘Great War’.

Barfield was disappointed that Lewis refused to go on talking about ‘Great War matters’. ‘All that is dead mutton to me now,’ Lewis wrote to Daphne Harwood on 28 March 1933:

and the chief points chiefly at issue between the Anthroposophists and me then were precisely the points on which anthroposophy is certainly right–i.e. the claim that it is possible for man, here and now, in the phenomenal world, to have commerce with the world beyond…The present difference between us is quite other. The only thing that I now wd. object eagerly to [in] anthroposophy is that I don’t think it can say ‘I believe in one God the Father Almighty.’ My feeling is that even if there are a thousand orders of beneficent being above us, still, the universe is a cheat unless at the back of them all there is the one God of Christianity.8

When, a few years later, Barfield tried to revive Lewis’s interest in the ‘Great War’, he replied in a letter of 28 June 1936: ‘When a truth has ceased to be a mistress for pleasure, and become a wife for fruit it is almost unnatural to go back to the dialectic ardours of the wooing.’9

The ‘Great War’ letters are the first part of the ‘Great War’ to be published. The originals of all the documents are held in the Wade Center, Wheaton College, with copies in the Bodleian Library. For a full and excellent account of the ‘Great War’ see Lionel Adey, C. S. Lewis’s Great War with Owen Barfield (Victoria, Canada: University of Victoria, English Literary Studies Monograph, no. 14, 1978; new edn, Rosley, Cumbria: Ink Books, 2002). Lionel Adey, who has done extensive research into the ‘Great War’, arranged the letters as they are given below.

SERIES I, LETTER 1

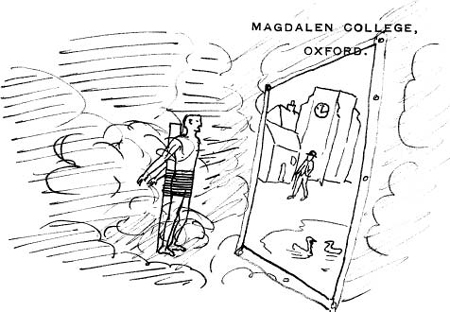

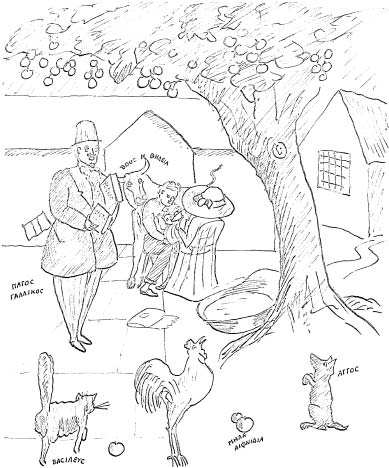

I have got led into an orgy of drawing: the pictures decrease successively in seriousness.

Magdalen College,

Oxford

[1927]

The real issue between us.

1. Agreed (by you and me, also by Kant, Coleridge, Bradley etc) that the discursive reason always fails to apprehend reality, because it never grasps more than an abstract relational framework. The question then is whether it is possible for us to know that Concrete in-which alone the thing we have abstracted was real.

2. Agreed (by us both, and many others) that the abstract reason plus sense experience plus habits etc gives us, in the phenomenal region, a substitute for knowledge which works tolerably well for practical purposes.

3. You maintain that this reason + experience + habit can and ought to be used to produce a knowledge of the supersensible, as confidently as it [is] used in the sensible.

4. I maintain that the distinction is between the real & the phenomenal, not the sensible and supersensible. In all cases we are trying to know the same reality. In ordinary science etc we see that we fail to know reality because we have not knowledge but only a convenient conventional symbolism: what is grasped by it is a substitute for reality wh. I call the phenomenal.

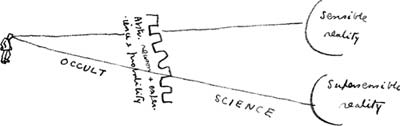

Your contention, therefore, is that something wh. is admittedly not knowledge of reality can be knowledge of reality, wh. is absurd. For whether you apply it to the sensible or the supersensible, such an instrument can’t give reality but only as much of reality as survives its lense–i.e. phenomena. Therefore all that your occultism can give us is not the Real instead of the phenomenal but simply more phenomena less surely grounded (in the empirical way) than the ones we have already, and less real because they claim to be more. For the highest merit of the phenomenon is to confess itself a phenomenon. This is the picture.

- 1. What you think you’re doing.

- 2. What you think I’m doing.

- 3. What I think you’re doing.

- 4. What I think I’m doing.

Wait a bit: this looks as if we were not part of reality. I put it better on next page.

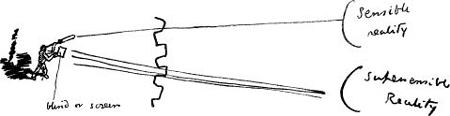

The clouds behind me are  . 10 The post to which I am tied so that I can’t turn round is finite personality. In front of me is a mirror representing as much of the reality (and such disguise of it) as can be seen from my position. It includes, of course, ‘myself’ as an empirical object. It is surrounded by a steel frame which represents the finitude and deadness of every mere object. I am studying the mirror with my eyes ([which] equal explicit cognition) but reach back with my hands so as to get some touch (implicit ‘taste’ or ‘faith’) of the real.

. 10 The post to which I am tied so that I can’t turn round is finite personality. In front of me is a mirror representing as much of the reality (and such disguise of it) as can be seen from my position. It includes, of course, ‘myself’ as an empirical object. It is surrounded by a steel frame which represents the finitude and deadness of every mere object. I am studying the mirror with my eyes ([which] equal explicit cognition) but reach back with my hands so as to get some touch (implicit ‘taste’ or ‘faith’) of the real.

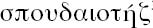

Here we see a gentleman (not identified) engaged on seeing whether a departure from dry academical methods and a newer, freer theory of knowledge may not get some new images out of the mirror. The mirror seems to be playing up well so far. Meanwhile the clouds have ebbed to his ankles. Something like despairing hands stretches to reach from behind but he doesn’t notice them. Overhead I detect a curious figuration of cloud that fancy may interpret as a gigantic face in laughter. The hammer and chisel are occult science, yoga, ‘meditation’ (in technical sense) etc.

An orful example. Study of a gentleman reaching vainly for the inner reality he has scorned, while he shrinks in horror from the phantom he has created on the black wall from which he has succeeded in chipping off all the looking-glass. (Only those who are not poets cd. get as far as this, of course) On a second mirror invisible to him but visible to his neighbours, ambulance, asylum, cemetery appear successively.

Lewis’s Series I, Letters 2 and 3 were answered by Barfield’s First Letter of 28 July 1927 which begins: ‘My dear Lewis, Here goes: however miserable a failure I may make of it, the mere attempt is going to be pure joy after a hideously “logistic” month.’

SERIES I, LETTER 2

My dear Barfield–

I hope to return your sister’s plays by next week. 11 I have read Caesar’s Daughter twice and am much impressed. The other I have doubts of, but have not yet come to a conclusion. I will try to give you a full critique when I next write. In the meantime I want to continue our own argument.

I must state, first of all, that truth seems to me to imply two terms: the one, an object or fact, the other a mental complex related to that fact in a particular way. 12 I say a complex because I think that when we know, we always know ‘that etc’ (an accusative with the infinitive), i.e. we recognise a whole of parts, or a unity in diversity: of a mere one I do not think there is knowledge, unless you mean knowledge by acquaintance which is different.

Truth, then, is a quality which cannot be attributed to any entity, but only to certain entities. Thus it cannot be attributed to a body. Nor, again, to a passion or emotion as such: for while an emotion can spring from, be accompanied with, or beget, judgements, opinions or expectations which are true or false, it cannot itself (so far as I see) have that sort of relation to an object which truth or falsehood demands. Indeed what would be object with respect of judgement etc. seems to be rather cause or end with respect of emotion. The question is whether poetic imagination is one of the things to which truth and falsehood can be attributed.

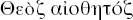

Now I take it for granted that truth and falsehood can not be asserted of ‘imagination’ in the common meaning, ( , 13 the imaginatio as a psychologist understands it). No doubt images may resemble realities (either individually or in their union) more or less accurately, but that is not truth or error. If it were, we should have to say that a person had truth when he didn’t know he had it (as where my images are more like the reality than I suspect), i.e. was in truth and error about the same thing at the same time. All that can be true or false here is my opinion or assumption, if I have one, about whether the images resemble reality or not. Until I have thus referred my images to reality, there is no truth or falsehood: and when I have, the images are not themselves true or false, but merely part of the subject-matter of an accompanying judgement which is true or false. 14

, 13 the imaginatio as a psychologist understands it). No doubt images may resemble realities (either individually or in their union) more or less accurately, but that is not truth or error. If it were, we should have to say that a person had truth when he didn’t know he had it (as where my images are more like the reality than I suspect), i.e. was in truth and error about the same thing at the same time. All that can be true or false here is my opinion or assumption, if I have one, about whether the images resemble reality or not. Until I have thus referred my images to reality, there is no truth or falsehood: and when I have, the images are not themselves true or false, but merely part of the subject-matter of an accompanying judgement which is true or false. 14

Now for you, if I understand you, poetic imagination is not any image, nor the having of any image: in fact images only appear as poetic imagination ebbs. And I think it would be fair to say that when the images do appear they are not true or false, and in this respect do not differ from the images I have been talking of in the last paragraph. In fact (would you agree?) they do not in their nature differ at all from ordinary images, but only in their origin. That is, the same raw material which in ordinary uamsara is ordered by memory, association, and physiological causes, is in this case ordered by a cause of a different kind.

It would follow, then, that when poetic imagination has ebbed and left us with its mere slot or track in the image of ‘an enchanted boat’, 15 that image is not false or true: tho’ of course we may (or may not) have opinions etc about it wh. are true or false. The truth wh. you attribute to poetic imagination must be located in the imageless state wherein the ‘light of sense goes out’ 16 and only there. For if I am right in saying that images in themselves cannot be true or false, this will hold of images however produced.

The image-al sediment left by poetic imagination, then, is not true: not because it is false or untrue, but because the standard true–false does not apply to it at all. The next question I raise is whether in addition to a sediment of images, there is also left a sediment of explicit assertion or belief. It seems to me that there may or may not be: but let us suppose that there always is. This assertion (once the inspiration is gone) will be conscious logical judgment and guilty of abstraction. It may, if it so happens, be true. But I argue that its truth cannot be the same truth which (as you maintain) existed in the moment of poetical imagination.

For (1.) if it were, we should then find that we were apprehending the same fact both during the poetic imagination and afterwards: that is, the poetic imagination could not differ from the subsequent normal judgement as far as concerns the truth grasped, but only in attendant emotion–wh. neither of us would admit.

(2.) It is contended that poetical imagination transcends the abstraction inherent in normal knowing. But the assertion left behind by the moment of inspiration would (by hypothesis, in the words ‘left behind’) be a specimen of normal knowing and the fact it grasps would be abstract. But if we could by normal knowing grasp the very same that we (as you say) grasped in poetic imagination, then the claim that imagination transcends the abstraction wd. have to be abandoned. I conclude then that if retiring imagination leaves behind it an ordinary assertion or belief, and if that belief happens to be true, its truth is other than the truth grasped during the imagination.

But, again, since the imagination was not logical or abstract, it cannot be logically connected with the judgment which it may leave behind. That is, the assurance that I grasped truth during inspiration, furnishes no logical ground for the truth of the assertions I find myself disposed to make when imagination has retreated. Again, since by hypothesis imagination has retreated and we have returned to the logical level, we cannot now effect any supra-logical connection between the present judgment and the past imagination. But since we can effect neither logical nor supra logical connexion, we can effect only infra-logical connection between them, that is, we unite the judgment with the precedent inspiration only by blind association.

From all this I conclude–and here I am v. anxious to know if you agree with me–that, granting the truth of poetical imagination, we can never argue from it to the truth of any judgment which springs up in the mind as it returns to normal consciousness. Thus I might hold that poetical imagination is true and that in reading the passage on death in Lucretius17 I participate in poetical imagination; and I might also find myself at the end of the passage spontaneously making the judgement that the soul is mortal: but I could not therefore be sure that that judgement is true. In other words we cannot transfer (at least it is not evident that we can) the assurance which the imagination gives of its own supra-logical truth to any normal act of opining or judging which it leads to. It vouches (if at all) only for itself.

It might perhaps be argued that while the judgement left behind by retreating imagination cannot claim the same truth which is claimed for imagination itself, still, as the work of a mind yet fresh from the springs of truth and not wholly subdued to its returning abstractness, such judgments may be at least nearer to the truth than those which we make at other times.

I need hardly point out that there is no â priori reason why this must be so, for it is just as likely that the crossing of the frontier shd. be marked by confusion of two modes of consciousness (therefore producing something less true than either of them working it its own way) as that it should be still lit up by the mode we are leaving: as when you change the focus of your telescope(1.) you get, during the transition, not vestiges of the higher power still surviving, but a mere blur and confusion which lasts until you are fully settled to the new focus. However, it may be so.

As far as my own experience goes (but I am now speaking with great hesitation) it does not bear this out. For it appears to me that experiences which I regard as being poetic imagination may leave me disposed to make judgments which are incompatible with each other: thus I have returned from what I wd. call inspiration–but v. possibly I have never known it at all, we can only put our furthest north and the pole may be miles away–sometimes convinced of the insignificance of the human spirit in the scheme of things, and sometimes of its divinity as lord of space and time and creator of all that it seems to be enslaved to.

Now, in any ordinary sense, both these judgments cannot be true. Of course we may say that if we cd. recall the inspired moment as it was, we shd. see how both these abstract opinions are pretty equally adequate symbols of a concrete truth that transcended them both. That is impossible to refute. But it leads to the very point I am now contending for.

If the truth of imagination differs so much from normal truth that ‘The soul is weaker than its world’ and ‘The soul is stronger than its world’ may both be expressions of it, then clearly imaginative vision cannot be invoked as a source of certainty for any one judgment as against another. 18 What lends its support equally to opinions that are contradictory to normal thought can really lend no support to either of two contending opinions.

So I return to my position, that even if poetic imagination has truth, it vouches only for itself. The explicit beliefs–whether dogmative or tentative–which spring up in the tracks of retreating vision must be tried on their own merits. If after reading ‘Huge and mighty forms that do not live Like living men, moved slowly through my thoughts By day, and were a trouble in my dreams‘19 I emerge saying ‘Why not? How likely that such things are’: and if the same day I read ‘When all is done, human life is, at the greatest and the best, but like a froward child that must be played with and humoured a little to keep it quiet till it falls asleep, and then the care is over’, 20 and emerge from that thinking ‘Yes. What are all our spiritual activities but a keeping ourselves snug and warm for a few minutes in this steppe of matter’,–then clearly I cannot use imaginative assurance in deciding between these two opinions.

No doubt, you may say that the propositions into which I ‘emerge’ are not the right ones to spring from the imaginative experiences incarnate in the two sets of words. So much the better for my argument: for the point I am making is that the truth of a proposition is not vouched for by the fact that it springs from imaginative experience: which you grant, if you admit that I had such experience and emerged from it into the wrong proposition. (I am admitting, everywhere, that the secret may be that I don’t have what you mean by poetic imagination, in wh. case cadit quaestio: 21 but we can’t keep on returning to that point and you wd. not be impressed by repeated humilities).

To say all this shortly: the trouble about the simple practice of writing ‘How true!’ in the margins of imaginative books, is that you will have to write it against passages that are (in any ordinary sense) incompatible with one another.

If this argument is grounded (and I invite correction) it would surely follow that, even if we were sure that we know in poetical imagination, we could never (except while enjoying inspiration) have any notion what we know. Thus you might well say ‘I am certain that there was truth in the experience I had when reading the myth of Persephone’: but you could never say ‘I know that Persephone exists’ (1.) or ‘I know that vegetation is not a purely chemical phenomenon’ or ‘I know that the soul is immortal’ or ‘I know that the soul and all other things die to live’: for every term in these propositions expresses not the imaginative moment itself but some part of the residuum of images or conceptions left behind, and, as I have tried to show, not vouched for. 22

And this is one of my chief difficulties: how I could mean anything by being sure that I was knowing a moment ago without having any notion what I was knowing. But I am far from certain that I couldn’t mean something. What I feel much more certain about is the illegitimacy of transferring the truth claimed for imagination to any concept or image which has happened (perhaps quite fortuitously) to cling to the moment in which inspiration occurred, whereby we accept the hands of Esau and overlook the voice of Jacob. 23 And that is partly why I still hesitate to ascribe truth or falsehood even to the inspiration itself–tho’ I have been granting it here for argument’s sake, and indeed think it quite possible, so far as I can see.

I hope I have incidentally cleared up what seems to be a slight misunderstanding in your letter. You seem to suggest that the only alternative to holding that poetry is veridical is to hold that poetry is ‘fantasy’: by which I think you mean to imply something of falseness or triviality. Of course, in denying that poetry is true, (at present I don’t deny, I only question) I should never dream of asserting that poetry was false: any more than in saying ‘The stars are not moral’ I should mean to assert that the stars were immoral.

It is not a question of something admittedly in the class of things to which such words as true and false apply, of which we are then asking ‘True or false?’. On the contrary it is a question as to whether something, wh. we both admit to be most serious and valuable, does belong to that class of things about which the enquiry ‘True or false?’ can be significantly raised.

If I knew that poetry were in that class I should unhesitatingly pronounce it true: I am certain it is not false. In fact I hesitate to call it ‘veridical’ because I am not yet sure whether it is ‘-dical’ at all or not: because I still think Sidney may have been right when he said that the poet alone never lied because he alone never asserted. 24 What I can never see is that the suggestion of aesthetic experience not being ‘-dical’ should be regarded as equivalent to the suggestion that it is not an absolute spiritual value. You would find no difficulty in attributing such value to moral good, and there the ‘-dical’ element has never (so far as I know) been suggested by any person except one, whom Hume exploded. 25 Why should not the value of poetic imagination differ as much from knowing and doing as they differ from each other? Have you so exhausted in your survey the horizons of the spiritual world that you are sure there can be no other value than that one of Truth with which you seem at present most concerned, and that you can therefore affirm that if Beauty will not be taken in as a door keeper to Truth, or as Truth’s domino, her occupation must be gone? These things may be true. But where did you learn them? Never where you learned your singing. 26

From what you have said at various times I gather that your real reason is a fear lest, if the value we find in beauty cannot be claimed as a kind of Truth, it will turn out to be nothing but pleasure under a pompous name. I admit that this fear lest values should be only pleasures is apt to beset us in all cases except that of moral good. I can therefore see a very good case for the Kantian doctrine that morality is the only real spiritual good. 27

But I can see no case, prima facie, for erecting Truth into the sole good. It seems to me just as easy to suppose that a man engaged in the pursuit of truth is merely amusing himself as to suppose the same of the man who pursues beauty. It seems just as odd to call a tragedy ‘pleasure’ as to give that name to the labours of study. It is certain that we feel obliged to abandon proffered truth as well as proffered beauty in favour of doing, as often as an interrupting duty knocks at our door. So that the root of your insistence on the-dical (as the presupposition of the veridical) character of imaginative experience–or what I take to be the root–seems to me to be an error.

Because imaginative vision is a serious and valuable activity of the spirit, you cannot therefore conclude that it is-dical. I have often wondered whether its value might not even be much more like the moral value than it is like truth: whether, instead of giving us a new cognitive attitude to reality, it might not give us an enriched and corrected will, so that we returned not to know more, but to do and feel as if we knew more. 28

But this is purely speculative. I am wholly in the dark as to whether beauty is at all like either truth or goodness, or less like one than the other. But it would only darken the matter for you to tell me that if it is not truth it must be fantasy–until you have proved that there cannot be an independent value other than truth: which, for all I know, you maybe ready to do.

I shd just add that, while I have assumed throughout that the really valuable thing is the imageless & wordless state before the images come, I am, as a matter of fact, often doubtful about this.

Yrs

C. S. Lewis

P.S. If you wish to continue the discussion you had better return this with your answer & I will do the same to you, so that I can correct myself & not fall into inconsistencies. I am trying to avoid all mere contentiousness and to be careful not to let anything run away with me.

SERIES I, LETTER 3

[July 1927]

My dear Barfield–

I enclose (1.) your sister’s plays (2.) Canto I of the ‘Hag’. 29 As to (1.) I must begin by apologies for the unconscionable time I have taken to send them back. I read them almost at once and have since re-read them and have been putting the matter off because I really found it so difficult to make any criticism.

Very roughly, what I have to say is that Caesar’s Daughter seemed to me a very interesting and amusing play, and that I couldn’t understand the Martyr: but those are both rather useless remarks to the author. In the Martyr I think what chiefly worried me was the character of Miranda. I can’t follow her motives and I don’t know what sort of person she is. I once or twice suspected her of a purely literary parentage–the hackneyed buona roba30 of modern fiction who has the right of acting inconsequently and being credited with profound interest whatever she does: but I am too much in the dark to push the charge.

On Caesar’s Daughter I have only one serious criticism to make: i.e. that the two most serious scenes–that between Estelle & Claude in Act II and between Claude and Cecily at the end–reach their degree of seriousness rather too abruptly: and that in such passages as ‘Reality is a cold thing but it wears well’ (you needn’t ask if I liked that!) the dialogue seemed too great for the situation. Some hint of that  31 underneath all the ordinary comedy-of-manners from the beginning ought to be possible, tho’, of course, I am aware how dangerous the attempt to supply it must be. I also felt that Claude’s succumbing to Estelle (and Austin’s to Miranda) were unconvincing: but I suppose the actors will do all that for you. What unfair advantages a dramatist has!

31 underneath all the ordinary comedy-of-manners from the beginning ought to be possible, tho’, of course, I am aware how dangerous the attempt to supply it must be. I also felt that Claude’s succumbing to Estelle (and Austin’s to Miranda) were unconvincing: but I suppose the actors will do all that for you. What unfair advantages a dramatist has!

I am afraid that is all I have to say–unless I add (what is perhaps more important) that I found both plays interesting to read and retain a pretty lively impression of most of the characters: that is, they come alright over the first fence that any book has to get over: they didn’t bore me.

As to the ‘Hag’–you will not, I hope, allow my recent talk of abandoning poetry to influence you in the direction of taking too favourable a view on the ground that I ‘need’ it psychologically at present. My quarrel with the muses is not likely to last very long. Make any marks or scholia you wish on the MS and return it to me when you can.

I certainly haven’t forgotten our argument about imagination: in fact I have only recently stopped watching the posts for your answer. I feel we have got onto the root difference between us now, from which all the others spring, and am very anxious to hammer it out. I think we should continue the controversy by letter with some degree of care and method: that is more likely to lead to a result than chipping away at each other when we meet, when I am alternately swayed by the two opposite tendencies, one, mere contentiousness, and one, the desire to slur things over and assume more agreement that there really is. I am always too implacable at one phase of the conversation and too pliable later on.

By the bye, I think in my letter I used the words ‘logical judgment’, in talking of the judgment we might make after inspiration had ceased. It has just occurred to me that this may breed misunderstanding. I don’t mean necessarily a judgment in the forms given in a book on Logic. We should remember that, after all, ‘logic’ is the name not of a kind of judgment but of the science which attempts to give a formal account of the faculty of judgment. The question ‘is this a logical judgment?’ shd. be understood as meaning ‘does the formulation of all judgment attempted by logicians cover this case?’–i.e. it is a question not about the nature of this judgment so much as about the success of a science. I think myself that all the judgments we make can be got into the forms acknowledged by logicians, but I don’t in the least want to discuss that. All I meant really was a normal or uninspired act of assertive thought: one which could be argued about and proved or disproved by people who have no other qualification than a knowledge of the terms involved and ordinary clearheadedness. 32 One might almost define a ‘logical’ judgment in the sense I intended as ‘any thought which can be equally truly expressed by any number of educated people in any number of modern languages’. I say all this to avoid the red herring of a discussion as to whether our ordinary thinking is ‘logical’ or not. That is not our question (as far as I can see). Our problems are

1. Is imagination in the common sense (i.e. the image-making faculty) capable of being true–false (i.e. is it-dical)?

2. Is imagination in the other sense (i.e. a faculty operating without either images or concepts)-dical?

3. If it were, could we in our ordinary everyday judgments recover (or know or ‘say’) what imagination had ‘said’ (or known) or connect it in any way with our everyday judgments?

As to my movements:–Mrs. Moore is not well and there was a threat some time ago of an operation (not at all a serious one in itself, but the state of her blood, having once had thrombosis, makes any operation rather serious for her). 33 We have now some hope that it may not be necessary, but are still uncertain. Secondly, my father is not well, having suffered from rheumatism and lumbago for a considerable time: and when and if Mrs. Moore’s trouble is settled I must try to get him to come over to England, and go with him to Droitwich or some such place. 34 (My brother is in China which leaves me the only person to deal with my father).

As you see I shall thus be in the hands of the Categorical Imperative pretty well all this summer: and if any interstices are left, examining and preparing work for next term will fill them up quite comfortably. It is therefore v. unlikely that we shall be able to meet, unless I can come over for a day to see you at Long Crendon sometime.

I envy you the Highlands. It is v. odd (tho quite true) that you should be all for details in landscape while I am all for horizons, while in such things as literary history, or the history of thought, we change places, and you can detect the essential spirit of a thousand complicated years(1.) while I never dare to go beyond particular writers and characters. I hope it is doing you both good, and that Mrs. Barfield, who was rather run down when we last saw her, has recovered vigour (Antaeus-like) from the native heath. 35 (I can imagine the hills as you describe them with extraordinary ease and clearness).

Yrs

C. S. Lewis

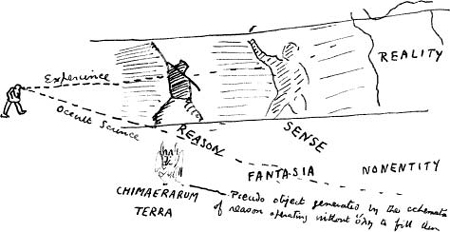

Study of a gentleman connecting what was given in imagination with his Everyday Judgments

SERIES I, LETTER 4

My dear Barfield,

I was confused the other day about the general and the universal. My first mistake, when I said that in the case of a universal we apprehended necessity, was to confuse the thing with our modes of apprehension. Of course a universal is what it is whether we are so lucky as to see it or not. The green common to many leaves is a universal whether I see why it must be common or not.

My second confusion was between universal propositions and universals. There are, besides universal propositions, general propositions: but we shall look in vain for entities called generals. Thus in the worst general proposition (e.g., ‘Small men are usually bad tempered’) the things are universals,  (?)36 and

(?)36 and  .37 Now we can get to work.

.37 Now we can get to work.

Universal propositions assert a connection between universals. All bodies occupy space, i.e. To-be-a-body (one universal) involves to-occupy-a-space (another universal). Universal propositions are of two kinds.

(a.) Certain. We cannot be certain of the connection between two universals unless we see necessity, i.e. necessity is not the characteristic of a connection between universals so much as the means by which we apprehend it. (Not a characteristic of connexion because presumably it is [not] a characteristic of anything).

(b.) Probable where uninterrupted uniformity in the accompaniment of two universals up to date is taken as symptomatic of necessary connexion. E.g. To-be-a-man has always been accompanied by to-be-mortal. (Of course there is no question that such accompaniment must mean the necessary connexion of some two or more universals. What is only probable is that we have pitched on the right ones. Thus it might turn out that to-be-mortal was necessarily connected not with being a man but with inheriting original sin or failure to take thyroid gland. The universal propositions of science are only probable because we do not really know which universals are really connected and which are merely going about together by accident (i.e. as a result of connections lying farther off.)

General propositions assert that two universals have been found together very often, without even enquiring whether this is symptomatic of necessary connexion or not. The propriety of such propositions depends on the speakers estimate of what constitutes very often, and for this reason no proof or refutation is really possible except where the parties agree in their estimate.

N.B. Type (a) is irrefutable and no contrary instance can be found. Type (b) is refutable by a single contrary instance. General propositions are refutable only by a number of contrary instances which the speaker regards as sufficient to conflict with his estimate of ‘very often’.

Maureen is better. Let me know in a week’s time when you think of coming to spend a night with me.

Yrs

C.S.L.

Will this do as a definition of Myth?

A myth is a descriptionx or a story introducing supernatural personages or things, determined not, or not only, by motives arising from events within the story, but by the supposedly immutable relations of the personages or thingsx: possessing unity: and not, save accidentally, connected with any given place or time.

(A Legend is a story attached to a context, in a place and time series accepted as real by the teller, itself believed by the teller to be true, but departing from truth unconsciously, or without full consciousness, in the interests of greatness, the marvellous, or of edification.?)

SERIES I, LETTER 5

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

Do we still agree on the following points?

(1.) That the images connected with a moment of imagination are not the imagination itself.

(2.) That these images need not be, usually are not, copies of anything existing in rerum natura, i.e. their reality is simply that of being real events in the mind of the individual. (i.e. real as errors and hallucinations & emotions are.)

(3.) That the concepts suggested by a moment of Imagination are not the imagination itself.

(4.) That these concepts need not be, usually are not, copies of anything existing in rerum natura etc.

(5.) That the moment of Imagination does not vouch for the truth of any assertion suggested by it + made with the images or concepts suggested by it.

(6.) That therefore no moment of Imagination can be cited as evidence for any assertion whatsoever, except the assertions wh. follow not from its content but from the mere fact of its occurrence (e.g. it wd. be evidence, of course, for the assertion ‘This moment of Imagination occurred.’)

If so, the state of the case seems to be as follows.

(1.) B. and L. 38 agree that there is a valuable activity called imagination–wh. is not the same as imaginatio, uamsara, the image making faculty–the exercise of which is necessary for the conaissance of meaning.

(2.) B. and L. agree that the exercise of this faculty does not enable us to make true statements or judgments (though of course no statement, even a false one could be made without it, as is shown by (1.))

(3.) B. maintains & L. questions a doctrine that this faculty produces Truth, tho’ not true statements or judgments; and that this is the only veritable Truth, ‘true’ judgments not being really ‘True.’

(4.) B. maintains & L. denies a doctrine (advanced, I think as interpretation of (3.)) that the mind can become aware of its own activity in thinking as something other than (a.) the content or object of thought.

L. is at present in doubt as to the exact connexion between (3.) and (4.)

(a) I’m not saddling you with the view that they are mutually exclusive: better ‘that the whole situation called thinking is not exhausted by what-appears-to-thought and a bare awareness, but involves also an activity of thinking, & that we can be aware of this along with, or over-and-above, the what appears.’

The following letter–Series I, Letter 6–was answered by Barfield’s Second Letter which begins: ‘My dear Lewis, I begin with a few detailed comments.’ Before Lewis wrote Letter 6 at least one of his letters was lost.

SERIES I, LETTER 6

My dear Barfield–

I am not sure whether we are wise to raise the question of metaphor as a  39 to the present argument: but since you have taken the initiative I will try to follow.

39 to the present argument: but since you have taken the initiative I will try to follow.

As a reply to your dilemma, that either there must be metaphor in which the respect of similarity is undiscoverable by reason or poetry must be ornamented prose, it wd., perhaps, be sufficient for me to say that I never admitted that metaphor was the essence of poetry. As a result of reading your thesis and of talks with you I am prepared to admit that I have in the past greatly under-estimated the part played by metaphor in poetry–have, indeed, been curiously unconscious of the amount of metaphor in even my own poetry. But I do not yet think that metaphor is poetry or poetry is metaphor: at most I think that metaphor is one of the most important tools of poetry. The question of how far poetry can go without it, how many lines of great poetry you could have without stumbling on metaphor other than that inherent in the language, is still for me an empirical question. I can only wait and see. I imagine that some of the greater speeches in the French classical drama wd. furnish interesting examples. 40

Thus far I am speaking polemically in self defence. I will now turn to your question of principle ‘Can all metaphor be reduced without loss of essential meaning.’ The answer is, certainly not: coupled with a vigorous denial of the charge that my view of poetry is asemantic.

Let us take the two propositions (a.) The Lord is my shepherd. 41 (b.) The Deity exercises a benevolent superintendence over human affairs. My idea of the difference between them is something like this:–‘deity’ ‘superintendence’ and the like are abstractions or abridgements: symbols which do not (in the rapidity of thinking) evoke any relevant image but which are understood to stand for an infinite number of concrete experiences (or, more strictly, for an element in such an infinite number) any one of which cd. be imagined if we chose.

In fact, they are counters. Or, actual experience (the whole, of which ‘sense’ ‘conception’ and the like are the abstractions–into which it can be split up ex post facto42 but out of which it cannot be constructed)–actual experience may be compared to real wealth (bread, wine, houses etc), and such terms as ‘deity’ and ‘superintendence’ to the system of credit, or to paper money. As it is impossible to conduct any developed economic operation in terms of the real wealth, so you cannot think without removing yourself from the thing really thought about to its counters or chits. But–just as the credit has no meaning apart from the wealth in the background–so the skeleton-conceptions live only in the light of the real which they represent: a thing v. different from them. It is therefore very necessary to go back now and then, either to an actual experience of the sort they abridge, or to the concrete imagination of such an experience. In so doing we see the meaning of the terms: or rather part of the meaning, for the abridgement is usually general while the imagination is individual (I say individual, not particular: it may for all I know attain sometimes to imagination of a concrete universal as an individual: I hardly believe that, but I don’t want to contradict it).

I am so far describing what poetry does in general, not what metaphor does. Poetry is therefore intensely semantic, but not at all assertive. You will easily see that to discover by imaginative energy what a proposition really means, or (as we say) ‘what it would mean to you’ if it were true, is quite different from discovering whether it is true. We can imagine a man weighing two rival hypotheses, and flooding each of them thus with meaning to its fullest: indeed no serious person does compare hypotheses without doing so. But this is not the same as converting either of them into belief. Only imagination can tell you what it would ‘mean’ if there were a god: but that doesn’t say that it tells you whether there is.

The relation between meaning and Truth seems to be this. A thing can’t be true or false unless it means something: but to find out what it means is not to find out whether it is true or false. Poetry can bring out the quality or whatness of the content of a hypothesis: but the truth of the hypothesis is known not by its content but by its connection with other concepts–by linking it with what is outside itself: and for this process (always a complex one) I think we have to use the credit system. (A good example of this vivifying of two hypotheses by imagination, utterly distinct from the assertion of either, is to be found in Arnold’s poem ‘In Utrumque Paratus.’)43 I hope you will allow that this view leaves poetry something more than decorated prose.

Now as to metaphor. ‘The Lord is my shepherd’ contains one concrete term (the only really concrete term?) and one (shepherd) which tho’ abstract, yet covers a far less variety of experience than ‘superintendence’, and has (owing partly to religious tradition, pastoral poetry etc) a much readier emotional response. In other words, when you think of ‘The Lord’ as my ‘shepherd’ you get at once something of the real flavour of care and protection–a little bit of the whatness wh. was merely symbolised in ‘benevolent superintendence.’ But I think everyone knows (so well that he needn’t say) those parts of the shepherd’s activities which provide some of the wealth to wh. ‘benevolent superintendence’ was paper money. We are thinking of the shepherd guarding, helping etc: not of the shepherd gelding, selling, driving to market. In other words the metaphor proceeds on a knowledge of the ‘respect’ wh. is tacit because it is so very obvious. And to change the respect is to make a new metaphor, not necessarily to make prose. e.g.

The Lord is a jealous god–a careful shepherd,

Tenderly (ah how tenderly!) guards my life;

Allows no rival in me, wolf nor leopard,

–My throat is sacred to the butcher’s knife.44

Surely that is at least tolerable pessimistic poetry: surely it is metaphor grasping similarity between an (evil) god and a shepherd: surely you understand it, and its difference from the other, just because you see the ‘respect’.

Again, can’t one make poetry out of the mis-taking in my last–i.e. the Lord does not feed me like a sheep but feeds my sheep like my hired shepherd? The old shepherd, bringing his sheep home from the mountain, hears the cry of a child from a neighbouring precipice. The evening is closing in–dangerous to leave his sheep–but humanity must come first–

‘There’s One above

Must be my shepherd till I come again.’

I’ll go further. In an Arcadian setting when you’ve got the reader accustomed to ‘my shepherd’ meaning ‘my lover’ in the mouth of a shepherdess, couldn’t an Arcadian St. Theresa say

Colin and Hobbin and Cuddie, farewell

–damn! I thought I had it all in my head but it’s gone wrong somehow. However, you see the possibility: you’d better write it yourself.

Well, for most metaphors, this seems to me the plain account. Poetry, in its task of revivifying ‘counters’–of establishing a gold currency–has to use every device (by wh. I don’t mean that all its tools are made logistically) to bring the thing home to your business and bosom. In fact, it has to be more accurate and concrete (less ‘in the air’) than prose. It does this sometimes by throwing at you a special case of the general principle (‘shepherd’–‘benevolent superintendence’): often by telling you what the thing is ‘like’ in the simplest, most sensuous sense (rosea cervice refulsit): 45 by rhythm (sunt apud infernos tot milia formosarum): 46 by telling you, or thrusting on your imagination, something quite different which has a similar emotional effect (‘the fat weed that grows on Lethe Wharf’): 47 by analogy a:b::c:d (passim) etc etc.

Now whether there is any instance of a metaphor wh. we can appreciate without knowing at all in what respect the things are alike, I really don’t know. I can’t think of one, but am ready for examples. Surely, in any case whatsoever, you wd. at least know that of several ‘respects’ suggested, some were nearer than others? e.g. does the likeness of soul & enchanted boat turn on 1. Non-existence 2. Speed 3. Beauty 4. Rarity 5. Solidity 6. Ease of movement. 7. Preciousness of cargo. 8. Danger 9. Unlawfulness 10. Probability of sea-sickness 11. Sense of power without effort.

Surely anyone knows that 1, 4, 5, 9, 10 are hopeless; 7 and 8 nearly so; 2 & 3 getting warmish; and 6 and 11 pretty near. However, I say, I really don’t know. But whether you can find out the respect or not, you certainly can’t (on my view) use a metaphor in an argument unless you’ve got hold of the respect. We have seen in the case of Lord–Shepherd that by changing the respect you change the whole thing. One ‘respect’ fits it into a pessimistic, the other into a religious view. Again, it is surely only when a metaphor comes off that you can dispense with enquiry into the respect. We are not agreed that your vegetable metaphor is a real parallel. How is one to discuss its claims? You must admit that sometimes bad metaphors are used in controversy, or good ones wrongly used. What is your weapon against a suspected metaphor in an argument? How does one discuss it?

About Croce. 48 Croce thinks that nothing assertive or cognitive can enter an aesthetic experience at all: that at the moment of enjoying a storm you cease to be aware that it is a real or imagined storm: the distinction disappears. 49 I think that the knowledge of the object’s reality or unreality survives and makes an aesthetic difference: that the fall of Rome differs aesthetically from the fall of Troy just because it is judged to be real. Not that the real is aesthetically better than the imaginary, but just aesthetically different. As a natural corollary, Croce thinks (like you) that there is strictly speaking no aesthetic experience of nature: for in being aesthetically experienced it ceases to be asserted as ‘Nature’: in fact you make your work of art out of it much as a painter does. This has always seemed to me untrue: the reality of the objects being to me the very differentia of my aesthetic experience of the  50 Again, Croce relegates all so-called experience of nature to a very low level–as incohate art: and in this I disagree with him. I have never considered my quarrel with the Croceans in connection with poetry. I don’t suppose these points really interest you much and only give them because you asked me. 51

50 Again, Croce relegates all so-called experience of nature to a very low level–as incohate art: and in this I disagree with him. I have never considered my quarrel with the Croceans in connection with poetry. I don’t suppose these points really interest you much and only give them because you asked me. 51

To return to the high-road. For heavens sake don’t imagine that I think that ‘is’ means ‘equals’. My point was that I thought your argument required it to mean ‘equals’ in a case where that meaning was even more than usually absurd. I thought you argued that because R grew into R2, therefore R ‘was’ R2 in such a sense that to know R was identically the same knowledge as to know R2. Now I still think that if ‘to know R’ was identical with ‘to know R2’ then R and R2 would have to be the same, merely statically identical thing. In other words, I don’t mean that two things are interchangeable: I accused you of implying, or talking as if, they were. (You are guilty, unconsciously, of an infuriating Tu Quoque. 52 Painfully disguising my scorn, I try to find as polite an equivalent as possible for saying ‘You’re the sort of who thinks that is means equals’ and then am answered–but the subject is too painful!) Having thus cleansed my stuffed bosom, I will ask you to attempt to believe the following statements

1. I am aware that a problem about predication arose in Greece: as to how if sugar was sugar and sweet was sweet, sugar could be sweet (‘Oh S is S, and P is P, and never the twain shall meet.’)

2. That I am aware of, and agree with, Plato’s  53 and that I never made a joke about the one and the many to a Scythian policeman. 54

53 and that I never made a joke about the one and the many to a Scythian policeman. 54

3. That, whether rightly or wrongly, I believe that the problem about the one-and-many in R and R2 is not the problem you are talking of, at all. 55

The old problem about predication wd. be ‘If the Real is Real, and Known is Known, how can the real be known.’ In other words, how can we explain the unity existing between distincts wh. stand in a subject–attribute (S–P) relation to each other. Or, but differently, if white, square, sweet are many, how can sugar be white, square, sweet, and yet be one? But the relation between R and R2, i.e. between phases of an individual is not an instance of SP relation at all. If you have a solution of how acorns can be hard, you haven’t thereby got a solution of how acorns can become oaks. You can’t mean that when you say ‘Acorns become oaks’ you predicate ‘oak’ of ‘acorn’ as in saying ‘Acorns are hard’ you predicate ‘hard’ of acorn: and no language that I know wd. allow you to use the same copula ‘is’ in both cases. Whatever may be the true nature of predication, it is something different from the relation of R to R2.

Even suppose it were the same: it wd. not serve your purpose. The sort of identity you want is the sort which wd. make knowing R the same as knowing R2. But the identity-in-difference, whatever its real nature, between S and P does not fulfil that condition. ‘Socrates is a man.’ But if whenever you tried to know Socrates you succeeded in knowing only Man, that wd. surely mean that you had failed to know the individual Socrates. And if when you tried to know Man you succeeded only in knowing Mortal, then you wd. have failed to know that special variation of the mortal theme wh. constitutes man.

My answer, then, is (a.) That the relation of R to R2 is not an example of the ‘is’ relation at all. (b.) That even if it were, my original objection wd. hold. As to my ‘rigid’ conception of change, I use the symbols R and R2, instead of X and Y, in order to remind ourselves that R2 is not sheerly ‘other’ than R, but is in some sense the same–that there is an identity in diversity between them. I am not, I hope, trying to saddle you (unfairly, as it would be) with the view that they are just two utterly separate ‘things’.(1.) We are agreed that if the change from R unknown to R known were really like the change of a biological individual from one phase to another, then there wd. be identity of some sort between them, there wd. not be mere plurality.

The whole question is whether it wd. be identity of the sort needed to make knowledge of R possible. In the example just quoted we have a specimen of two terms ‘Socrates’ and ‘Man’ between wh. there is certainly some identity, but identity of a sort which does not mean that if you cd. only know Man you cd. be said to know Socrates. Quaesitur, 56 whether the identity between R and R2 is also of that (unsatisfactory for us) sort, or of a different sort. Surely, even if you can say that the vegetable soul is the seed, and is also the flower (tho’ I doubt if you can say even that), still you can’t say that the seed or the flower is the vegetable soul? Is there not here a ‘one-way’ relationship. If you substitute ‘becomes’ it seems even more so. The soul (w) becomes the embryo, the adolescent and the adult, but they don’t become it. Or again, to know w might be to know the phases, to know a phase wd. not be to know w. 57 And, I take it, R2 is a phase: and whether R is parallel to w or only to an earlier phase, I can’t say that R2 would be R, or to have R2 wd. be to have R.

The point is crucial, because, as I hinted before, the possibility of even stating your doctrine depends on some elucidation of the special way in wh. R ‘takes the form of consciousness’ in the case of knowledge: without that you will surely be up against my original difficulty that ‘a donkey’ and ‘reality taking the form of a donkey’ are all one. Any consciousness whatsoever is a specimen of ‘reality taking the form of consciousness’. (By the bye, don’t be sure that by coming into my room at 3 A.M. you will catch me napping: you wd. certainly say ‘This is Lewis’, but why? If I remained in that state for 20 years, wd. you say that the silent figure was me? If you had never come across sleep before, wd. you call it me in any case? Surely you say ‘This is Lewis’ by an ellipsis–as you say, pointing to what is still a mere swell ‘Here comes another breaker’–because long habit has taught you that from this breathing image (strangely unlike me even in face if you hold your candle nearer and use your eyes) you can at will evoke what you call Lewis? If you for a moment doubted that, you wd. not call it me. More philosophically, surely you don’t really think that any temporary manifestation of me, sleeping or waking, is Lewis? I am or become all of them: but no one, and no aggregate, of them, is me.)

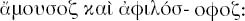

You say that you find no insuperable difficulty in reality existing  58 with respect to one knower and

58 with respect to one knower and  59 with respect to another. You agree that without the clause ‘in respect to one knower–in respect to another’, this wd. be mere staring Bedlamite nonsense? Reality can’t, I trust, really be in itself both

59 with respect to another. You agree that without the clause ‘in respect to one knower–in respect to another’, this wd. be mere staring Bedlamite nonsense? Reality can’t, I trust, really be in itself both  and

and  . Surely you can only mean that reality, wh. is always itself, can be differently related to different knowers: as Rose (which is

. Surely you can only mean that reality, wh. is always itself, can be differently related to different knowers: as Rose (which is  )60 can be differently related to different trees. And doesn’t this mean that the difference between truth and error, or the change from unknowing to knowing is not in the reality known?

)60 can be differently related to different trees. And doesn’t this mean that the difference between truth and error, or the change from unknowing to knowing is not in the reality known?

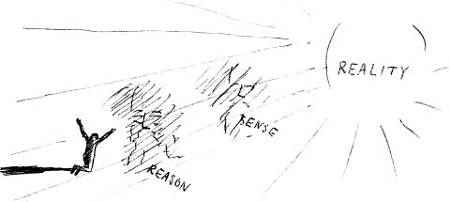

You seem to have misunderstood my taking of the smoked glass metaphor. 61 I never meant to take the hills literally and the other part metaphorically. My scheme was Hills = The Real, the great What-What. Glass = finite personality, categories, forms of sense, sensuous machinery. Picture as seen in glass =  62 (at wh. stage, of course, ‘hills’ in the literal sense first appear.) I thought we both believed in the Ding an sich, 63 in the sense that if there is appearance there is something that appears. I, at any rate, don’t accept a world of pure smoked glass. What I meant was that if I ever could know the Real (= wipe the smoke off the glass) that wd. be an event or change in me not in the Real (= the hills). If you don’t mean by real (1.) The single and unchanged (I mean qua relevant change) source of varying phenomena, varying according to point of view etc (2.) The common source of each individual’s private phenomena (3.) The reservoir of all possible phenomena never exhausted in any–then, I confess, I can’t see what ‘real’ means, except as a eulogistic term applied to those parts of our essentially erratic, subjective experience wh. you happen to like. (But read Dymer Canto VIII).

62 (at wh. stage, of course, ‘hills’ in the literal sense first appear.) I thought we both believed in the Ding an sich, 63 in the sense that if there is appearance there is something that appears. I, at any rate, don’t accept a world of pure smoked glass. What I meant was that if I ever could know the Real (= wipe the smoke off the glass) that wd. be an event or change in me not in the Real (= the hills). If you don’t mean by real (1.) The single and unchanged (I mean qua relevant change) source of varying phenomena, varying according to point of view etc (2.) The common source of each individual’s private phenomena (3.) The reservoir of all possible phenomena never exhausted in any–then, I confess, I can’t see what ‘real’ means, except as a eulogistic term applied to those parts of our essentially erratic, subjective experience wh. you happen to like. (But read Dymer Canto VIII).

Many thanks about the Greek jaunt: but it is not a question of money. 64 I have two quite distinct sets of claims upon my (not very extensive) leisure: in fact, two families, one natural, one chosen. Both contain people who are no longer young and who are in poor health. I am always skimping Belfast for Headington & Headington for Belfast, my friends for both, and all for my two distinct works (writing & tutoring). This very difficult adjustment of contending claims (all of wh. I gladly & affectionately accept) cd. hardly be eased by running away abroad for several months. Strange as it sounds, I am rather seriously wanted in more places than one in England whenever I am at liberty. I know that the laziness of an unadventurous man may disguise itself as a claim of conscience: but I have thought that over and one must rely on one’s own judgment. So I can’t come. I speak of my own affairs with some difficulty, & I don’t think it conduces to the right sort of intimacy (male intimacy) to do so v. often: you will understand that this is said in a confidence so strict as to exclude our most intimate ‘mutual’ (wrong use!) friends: and said at all only because I thought you entitled to a sincere and final answer.

How goes the novel? 65 The hag is going fine. The surf bathing (without boards wh are as comfortable companions in rough water as hedgehogs in a nuptial bed) is fine.

Yrs

C. S. Lewis

SERIES I, LETTER 7

My dear Barfield–

Sorry, but I can’t see why you compare Theaetetus 156 A, 66(1.)

for I can see no comparison. Aristotle (and you and I) were talking about an essential difference between soul doing, and soul suffering.

for I can see no comparison. Aristotle (and you and I) were talking about an essential difference between soul doing, and soul suffering.

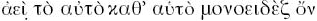

In the passage in Theaetetus, in the first place, the account is not Plato’s own but what the materialists say: and tho’ it does help on the argument, it is cited largely pour rire. 67 For tho’ they are  68 they are only so, compared with the wholly

68 they are only so, compared with the wholly  69–i.e. he is citing the right wing or the most reasonable part of those who believe in the Heraclitean & Protagorean doctrines.

69–i.e. he is citing the right wing or the most reasonable part of those who believe in the Heraclitean & Protagorean doctrines.

Secondly, it is all concerned, not with any distinction of one soulelement from another, but with the status of sensibilia.70 Thirdly, so little of the real difference (from our point of view) between Poetic & ‘Pathetic’ comes in, that I think, if you work it out, you will find it makes no difference which way round you take it. It isn’t clear whether the active  71 produces

71 produces  72 of which the passive

72 of which the passive  is the

is the  , 73 or the active

, 73 or the active  exercises

exercises  on the

on the  wh. are passive as ‘being seen’, ‘being touched’ etc.

wh. are passive as ‘being seen’, ‘being touched’ etc.

But it does not matter at all. The whole point is that sensibilia arise from some kind of co-operation between complementary  , and that the organ and the object, apart from that moment of co-operation, can hardly be conceived (

, and that the organ and the object, apart from that moment of co-operation, can hardly be conceived ( ). 74

). 74

That is all he is saying–as part of the criticism against Th’s second ~ ay attempted definition of  75 What that has to do with poetic & logistic, I can’t see. And it worries me rather. When you have found out, let me know which of us is escaping his own notice being an ass–for at least one of us must be

75 What that has to do with poetic & logistic, I can’t see. And it worries me rather. When you have found out, let me know which of us is escaping his own notice being an ass–for at least one of us must be

Yrs

C. S. Lewis

SERIES I, LETTER 8

Little Lea

Strandtown,

Belfast

[January 1928]76

My dear Barfield–

We certainly seem to be getting visibly nearer to the real point at last. We are agreed that metaphor (and also, I would add, music or in some few cases even rhetoric) may develop a What: and equally agreed that it cannot demonstrate a That.

The question as to its position in argument seems to me extremely subtle and delicate. We are discussing, say, the nature of knowledge. There is no doubt that a metaphor, if you are a good enough poet, may give me the whatness which you conceive to be in knowledge: and that is an indispensible preliminary to our discussion. But our discussion really takes the form (does it not) of a question ‘Is knowledge what you say it is.’

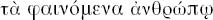

I must first of all find out what you mean by knowledge: but that is only a prelude to finding out whether you are right in meaning so or not. And the question ‘are you right’ is one of Thatness: whether this ‘what’ which you present to me is actually given in instances which we should be prepared to call knowledge. Or, to put it in another way, we cannot (strictly speaking) be agreed about a whatness. We can share a whatness by sense or imagination, and can then agree or disagree as to whether this whatness is realised in such and such an actual or no. For you will observe that whatness does not contain actuality: the bringing before the mind what X is, is preliminary to the question whether X exists. You cannot get the that into the what as an element: it was the mistake of Descartes to suppose that you could. (I take it this may be what Plato means when he says that good is  on the far side of being.)77 If you agree with this, you will see that the question whether knowledge is mainly What-ish or mainly That-ish, is not a question of emphasis.

on the far side of being.)77 If you agree with this, you will see that the question whether knowledge is mainly What-ish or mainly That-ish, is not a question of emphasis.

There is an ambiguity of language here. Suppose a man ‘knows the nature of Reality’ You may say ‘Is not this knowledge par excellence? And is it not, as the very words express, knowledge of a whatness?’ But the sentence must mean either (a.) He knows what the nature of the real is = he knows that this (imaginatively or sensibly realised) character does belong to the real: in which case knowledge turns out to be a that: or (b.) He ‘has before’ him a certain whatness which as a matter of fact does belong to the real: but its belonging to the real is a fact for us and cannot be included in his imaginative grasp of the whatness. All he can have, before you reach the that, is ‘a’ nature: whether that nature is anywhere realised, whether it is subjective or objective etc. are all questions which have no meaning except on the supposition that he has already grasped the nature: and for that v. reason the grasping of the nature must be prior to, and distinct from, those questionings, and (a fortiori) from their answers.

But we need no philosophy for something which experience daily forces upon us. Faced with a problem, we at once say ‘X might be Y…or Z’. Y and…Z are hypotheses, sometimes logistically contrived, sometimes flashed upon us by metaphor: and some such hypothesis is necessary in order for us to ask a question. I grant that in asking the right questions, imagination is paramount. But all that has to be done before an answer can arrive: an answer which will consist in establishing the certain or probable actuality of one of the hypotheses already suggested and grasped by imagination.

To say, therefore, that imagination is knowledge, or that knowledge is of whatness, seems to me like saying that to wonder is the same as to know, that there is no difference between doubting and discovering, that a question is the same as its answer, and that the solution of a problem is the problem itself. For what do all these terms, ‘doubting’ ‘wondering’ and the like, mean, except to have before ones mind ‘floating’ or unasserted whatnesses–the work of imagination which both calls them into being and is their being–which cannot yet be attributed to reality: and what does knowing or ‘solving the problem’ mean, but linking one of them up with that whole system of assertions which we call the real and therefore excluding the others?

It all comes to this. To wonder is to have hypotheses. To have hypotheses is to imagine. But to know is to have one assertion, and one or more rejected hypotheses. Now can these two states be called the same, except in some sense in which ‘same’ can be applied [to] thirst and drink, the G.W.R. 78 mainline and Paddington, to everything and everything else?

You will see that I cannot answer when you ask whether metaphor is ‘an effective demonstration What’. Do you mean a ‘demonstration what this is’. But such demonstration (in spite of the form of words) is really a demonstration ‘that’: a demonstration that the whatness you have grasped is actually given in the ‘this’ we are discussing. If you mean a ‘demonstration’ in the primitive sense, a displaying or exposing, of the unattached ‘whatness’ in your mind, which I have to receive (to the best of our common abilities) before I can either affirm or deny that it is actualised here or there, the Whatness which must be common to us before we can even disagree (for only in so far as I deny what you affirm is there real disagreement between us), then I agree.

But do not be misled by the word ‘demonstration’. That which is the preliminary of disagreement, which is as much the condition of your being refuted as of your making your point, is clearly not ‘demonstration’ in the sense of ‘proof’. It is simply the mental equivalent of what would be pointing in the sensible sphere. The three huntsmen all pointed at the object before ‘The first said ’twas a hedgehog, The second he said Nay.’ The pointing was not the argument, still less the entelechy of the argument into knowledge: tho, I grant, there could have been no argument without it.

Now for your two v. difficult leading questions. (1.) Does a poet in observing or intuiting a resemblance (which he will afterwards express in a metaphor) note an identity in difference in substantially the same way as a man who is making a judgment.

( .) Psychologically–i.e. as regards the consciousness of the man or the poet at the moment, I think the answer is No. The judging man is more clearly conscious of the respect of similarity; the poet (at least the only one I know really well) is often conscious only of the result, i.e. that the sensible image somehow fits in: how, why, or how far, he does not consider at the moment. In fact he is empirical: he judges by results. It gives him ‘the right feeling’ and there’s an end on’t.

.) Psychologically–i.e. as regards the consciousness of the man or the poet at the moment, I think the answer is No. The judging man is more clearly conscious of the respect of similarity; the poet (at least the only one I know really well) is often conscious only of the result, i.e. that the sensible image somehow fits in: how, why, or how far, he does not consider at the moment. In fact he is empirical: he judges by results. It gives him ‘the right feeling’ and there’s an end on’t.

( .) Logically. No. The judging man asserts that the identity in question holds good of reality: that it is connected (not only to him at that moment, but for all rational beings) with the system of assertions which he calls real. The poet does not assert this; he does not even raise the question. This Pity at this moment calls up ‘a naked new born babe’ 79 for those in tune with the situation. Whether he raises the question afterwards as to the universal validity of the identity, probably depends on his character & circumstances, not quâ poet, but qua Master W. Shakespeare.

.) Logically. No. The judging man asserts that the identity in question holds good of reality: that it is connected (not only to him at that moment, but for all rational beings) with the system of assertions which he calls real. The poet does not assert this; he does not even raise the question. This Pity at this moment calls up ‘a naked new born babe’ 79 for those in tune with the situation. Whether he raises the question afterwards as to the universal validity of the identity, probably depends on his character & circumstances, not quâ poet, but qua Master W. Shakespeare.

( .) Ontologically. i.e.–apart from the way in wh. they get to the identity, is it, as a matter of fact, the same identity in both cases. Answer–I don’t know.

.) Ontologically. i.e.–apart from the way in wh. they get to the identity, is it, as a matter of fact, the same identity in both cases. Answer–I don’t know.

(2.) Was Kant right etc. I don’t know.

Now for your ‘snag’.

From the dismay (it is hardly too strong a word) with wh. you greeted my suggestion, made on our walking tour, that there might be no such thing as Ego in the ultimate sense (tho’ of course there might be phenomena called ‘me’ and ‘Barfield’), I confess I had concluded that for you, at any rate, the subject was an ultimate: and therefore that ‘here am I and over there is Reality’ was a scheme you refused to go behind. As I was very uncertain about my own powers of continuing an argument behind it (whatever might happen in odd moments when the light of soul goes out), and not perfectly convinced of the truth of my extreme ‘an-egoistic’ doctrine, I assumed subjects as the framework of our whole discussion. And if ‘we’ exist, i.e. real, but individual and separate, selves, I certainly think you must either ( .) Assume a reality which is something other than our thinking and common to us all, or (

.) Assume a reality which is something other than our thinking and common to us all, or ( .) Relapse into extreme subjective idealism, at least: more probably into solipsism. If the reality thought of is nothing more than the thinking, and if the thinking is that of a real individual Ego, then the world is the content of an individual, personal

.) Relapse into extreme subjective idealism, at least: more probably into solipsism. If the reality thought of is nothing more than the thinking, and if the thinking is that of a real individual Ego, then the world is the content of an individual, personal  80 and I (there’s only one of me) may as well cut my throat to night.

80 and I (there’s only one of me) may as well cut my throat to night.