This Supplement contains letters not included in Volumes I and II. The letters to Owen Barfield were omitted from Volume I for reasons of space. It was later decided to include in the Collected Letters as many of Lewis’s letters as possible.

After three unhappy years at Wynyard School, Watford, Hertfordshire–the ‘Belsen’ of Surprised by Joy –Warnie Lewis won his freedom and in 1909 he became a student at Malvern College, Malvern, Worcestershire. He was very happy there, and in May 1913 he became a school prefect. Jack Lewis, after two equally unhappy years at Wynyard School (1908–10), spent one term at Campbell College in Belfast, after which he was sent in January 1912 to Cherbourg School, a preparatory school in Malvern. It was only yards from Malvern College, and besides having his elder brother close by, he made a great deal of progress. At the time Jack wrote the following letter to his father, Albert Lewis was worried about Warnie who in May 1913 had been degraded from being a prefect after he was caught smoking.

TO HIS FATHER (LP IV: 36):1

Cherbourg.

22/6/13.

My dear Papy,

I am sorry you should be so worried about Warnie: I think I knew about it a day or two before you. However, I hope he will be more cautious in future.

On Wednesday, in consideration of the scholarship we went for a sort of an expedition to a place near here, which was rather enjoyable. We had a match, which we won, against the Old Boys on Tuesday. It is rather a pity that the Parents Match scheme has fallen through. Much as I admire the spirit of true and generous humour which has led you to spare neither physical exertion nor cab windows for the edification, instruction, and recreation of the people of Malvern, I cannot but think that you would add in no small degree to your own reputation as a comedian, and the pleasure of the spectators, by joining in a cricket match. The weather is still very hot here. Thank you very much for the 10 shillings. Only about 5 more weeks now.

your loving

son Jacks.

TO HIS FATHER (LP IV: 40–1):

Cherbourg.

Gt. Malvern.

29/6/13.

My dear Papy,

We–that is the top form–went to Worcester to see a county match the other day: and, although I am not interested in county cricket, we had a very pleasant outing. The weather is still very oppressive here.

I am glad, very glad, to hear that you have got rid of our offensive friend Harry. 2 Perhaps, as you say, the new men are worse, but as long as they don’t always work in front of the windows, I shall prefer them. There are only four more weeks on Tuesday. We had two matches this week, one of which we won and the other lost. I am afraid there is no more news.

your loving

son Jack

Warnie left Malvern College in June 1913. He was followed home by Jack, who before leaving Cherbourg won a scholarship to Malvern College. Warnie hoped to enter the Royal Military College at Sandhurst and pass from there into the Army Service Corps. For this he would need to pass the entrance examination, and Albert Lewis decided to have him tutored by his old headmaster, William T. Kirkpatrick,3 who was now living at Great Bookham, Surrey, and taking a few private pupils. Warnie reported to Gastons, Mr Kirkpatrick’s house, on 10 September, and Jack arrived at Malvern College on 18 September, expecting to be very happy at a place his brother liked so much. He was given a room in School House.

TO HIS BROTHER (LP IV: 72):4

[Malvern College

20 September 1913]

My dear W.,

The new pres. 5 this term are Stone, 6 Browning, 7 and Bourne. 8 We have got study 24, the one next the pres. room. In it are Hardman II, 9 whose brother you knew, Anderson, Lodge (whom I detest), and myself.

This letter is being written only to stave off Jacks. 10 I shall write to you more fully at my leisure. Tassel, 11 on hearing my name, inquired angrily if I were the brother of ‘that other one’. Is not recruit drill a great game? You must be having a pretty plugging time at Kirk’s? 12 Cheer up however, it is only for a short time. Smugy13 inquires more tenderly for you, and I hear from home that Kirk writes of you with great affection. I shall have to stop now as it is Hall. 14 So far Malvern has gone well.

your affect.

brother Jack

TO HIS FATHER (LP IV: 73):

[Malvern College]

22/9/13.

My dear P.,

I am very sorry to have to write for so many things, but it can’t possibly be helped. Could you please send me 7/-, as we have just had to pay for a study 5/6 each, and games and other subscriptions which will amount to about 3/-when all paid. How are things at home?

your loving

son Jack

TO HIS BROTHER (LP IV: 74):

[Malvern College

September 1913]

Dear W.,

Thanks for the letter which reached me during Monday breakfast. I am writing this in the seclusion of a newly bought study, and am consequently very bucked. I have asked Jacks about the pictures and he’s going to ‘see about’ them. I left 12/6 at home for the ‘History’. 15 On the last day of the hols. P. forced me to tell him where the attic key was. I really had no alternative but to comply. So far everything has gone quite well here. There are a good many enquiries about you and your estate. Can’t write more now.

your affect.

brother Jack

TO HIS FATHER (LP IV: 80):

[Malvern College

5 October 1913]

My dear Papy,

I was very glad to get a second letter from you last week. I think it would be best if you were to write to the Old Boy16 about my giving my drawing.

The winter has set in here already, and we have had heavy rain yesterday at a match against the Aston Old Edwardians17 which we won. I am writing the account of it which will appear under Hichen’s18 name in the Malvernian19–a curious but not disagreeable duty.

I have heard again from W. very cheerfully. I do hope he will get through this exam all right. However, even if he does’nt pass now, he will have another chance in the summer.

I have not heard from Tubbs20 yet this term, but I suppose I shall later on. Jimmy made rather a good speech to the school on the first Monday morning re his leaving. However, I don’t think he will be a great loss to us. I wonder whom we will get to replace the Old Boy? That will be rather a case of ‘after a well grace actor leaves’. 21

We had a long Mission meeting in the Gym. last Sunday, in which some person whose name I could not catch, spoke remarkably well. You must have had an intolerable time of it that Sunday. Poor W. complains bitterly that his only afternoon off is taken away from him by ‘kind’ people who force him to play tennis. If I had my way, every ‘kind’ person in Europe would be broken on the wheel.

your loving

son Jack

TO HIS FATHER (LP IV: 85):

[Malvern College]

13/10/13

My dear P.,

I should have liked very much to be an intelligent fly on the wall during R. Ponsonby’s22 visit to Leeborough. 23 How much did your amusement cost you? 24

Yesterday there was an entertainment in the Gym, a dramatic recital by W.’s friend who did the Jew scene from the ‘School for scandal’. 25 This time he was very good in a Jacobs story, 26 some bits of Kipling, and a satire on the trials of modern travelling. On the whole it was a very good show, although he overdid the thing in his serious bit, the ‘Ballad of John Nicholson’ by Newbolt. 27

In our form this week we had a most exciting thing; one of the questions in our weekly exam was to draw a picture illustrating an incident in the book of Cicero which we’re reading. My picture was marked top and pinned up on the form room door for several days. The James28 came down and said it was ‘spirited’–which may mean anything. This week we have got to make a translation of an ode of Horace into English verse. I ought to be able to do something there. 29

‘Antony and Cleopatra’ is a hopeless play when you get into it. Smugy thinks so too; but ‘Romeo and Juliet’ which we are reading out of school for the Lea Shakespeare is good. 30 I cannot write any more now as we have got to go to chapel.

your loving

son Jack

TO HIS FATHER (LP IV: 94):

Gt. Malvern.

Postmark: 2/11/13.

My dear P.,

Yesterday we had an event of great interest, the match of the Cherbourg Old Boys against Cherbourg. It was, of course, very pleasant to see the place and the people again, and I enjoyed it very much.

There has been another event this week also which pleased me, in the form of the classical orchestral concert, which was really exceedingly good. Among other items was a thing of Handel’s from ‘Berenice’, 31 which I had never heard before and which I liked, and the flower song from Carmen. 32 The singer, Hubert Eisdel33 broke down in the middle of the concert and could’nt go on. I felt very sorry for the man, as one must feel awful under such circumstances.

I suppose my half term report will reach you some time during this week. Write and tell me what it is like. I think Smugy knows that I am working, although I am very weak on some points. I cannot write more now as it is time for Chapel.

your loving

son Jack

TO HIS BROTHER (LP IV: 116):

Sunday,

Dec. 14th [1913]

Dear W.,

Write soon please and tell me when exactly you are coming down. I have’nt yet heard whether you passed your exams or not, but I should think you have. 34 Anyway don’t despair. Come down as soon as possible, say Wednesday. Can’t write more now.

your loving

brother Jack

P.S. Don’t be impatient about the sound box. I’ll explain my plans later on.

TO HIS FATHER (LP IV: 120):

Saturday.

Postmark: 20/12/13

My dear P.,

I am very sorry that you got worried about me this week. I really have not had twenty minutes to myself since Sunday: we have been busy with exams etc. W. says he is coming down here on Saturday, and we are travelling on Tuesday.

Thanks for the questions about the books. The only thing I can think of at the moment is Gray. 35 He is the only English poet of any standing that we have’nt got, and so will ‘fill a long felt want’.

I am very glad this term is over and am looking forward hugely to Wednesday morning. When shall we know about W’s. exam? This suspense becomes tedious. I can’t really write any more now, but I hope soon to talk with you in person soon. So good bye for a few days.

your loving

son Jack

TO HIS FATHER (LP IV: 141–2):

[Malvern College]

Postmark: 24/2/14

My dear Papy,

Judging by the descriptions enclosed lately in your letters of the social whirlwind at home, things are more than usually ‘merry and bright’. Perhaps I am better off in that way now than in the holydays–now that that fact compensates for the various other disadvantages of life in England.

Well, the poem36 was duly shown up. Although not ‘sent up for good’, it came out top, Smugy observing that he was tired of that metre; 37 so that you see my fears were not without foundation. However he shall not have the same complaint to make again, and it is to be hoped that ‘our muse’ flows in other rhythms as well.

Last night one Dr. Levick, who had chased the pole with Captain Scott, 38 came to lecture upon that subject. 39 Among other interesting facts we heard of their cutting up their dinner of seal meat with a geological hammer, because it was frozen so hard. And each fragment, as it was cut, leaped across the hut: behaving, in short, just as stone would under the circumstances. Carving in their latitudes has many aspects of art and difficulty unknown to us. But, on the whole, it was not a good lecture. He had a good many interesting things to tell, but could not tell them, and what is more, did not seem to be interested in his own story. The slides were excellent.

Last Sunday I think I told you that I was asked to go up to Cherbourg. At the risk of repeating myself I must tell you that I accepted and had quite a pleasant afternoon. But while I was there, I suddenly realised that it wouldn’t do to go back, although I have often felt wishes in that line. It is funny to think that you can quite drop out of the atmosphere of a place in a few months.

your loving

son Jack

TO HIS FATHER (LP IV: 184–5):

[Malvern College]

Postmark: 14/6/14

My dear Papy,

Thanks very much for the postal order which I was glad to get. But I had little pleasure from the sight of that alarming and disagreeable type written letter. I hope that there is nothing serious the matter, and that if there has been, it is now on the mend. 40 Mind that you see a really competent doctor if the thing keeps on being troublesome, not Squeaky. 41 What exactly is the trouble? As soon as you are able to write, don’t forget to let me know all the particulars of the case, as master Willy’s type is not a very comforting or reassuring missive. 42 Here, next morning ushers in Speech Week, with its gaiety and ‘patriotic’ rejoicings: we shall soon be singing sentimental songs about the ‘dear old limited company’, while some of us pretend and others are actually made to imagine that we like being here. What artificial nonsense it all is! I have read the ‘Prologue’ for speech day (composed by Smugy), a neat, epigrammatic poem of some 50 English heroic coup-lets. 43 But after that, how can anyone read these eulogies of our late headmaster with feelings other than contempt? Also the warm welcome to Preston? 44 Would they not have bestowed them with equal cordiality on anyone else if he had been our headmaster? Even if he had practically ruined the school, we should still go on talking complimentary drivel and telling lies about the great things he never did.

This week you will get the half term report. And I think I may say with confidence that there will be a considerable improvement. The Greek Grammar and other ‘bêtes noirs’ have been going much better this term, and Smugy waxed quite complimentary on the subject. 45

I do hope that by the time you read this you will be a good deal better: in any case, take care of yourself and don’t be rash.

your loving

son Jack

TO HIS FATHER (LP IV: 202):

[Malvern College]

Postmark: 20/7/14.

My dear Papy,

I need hardly say how very sorry I was to hear from Aunt Annie46 that you had got a relapse of your illness and were again confined to bed. I suppose the cause of it was that you were worried about business affairs, and went back to the office before you should have. You must be more careful next time: no matter what the state of affairs is. For as you yourself have often said, we shall always have enough to keep the wolf from the door: ‘and after friends have done with hunger’ as the shepherd says in Euripides, ‘if they have but each other and the good green earth, who is happier than they?’ 47 Annie has again written me a very kind and useful letter about your health: she is really very good over this business, both, as you tell me, doing all she can for you at home and at the same time trying to do her best for Warnie and me abroad.

On Thursday night Preston invited myself and two other people to dinner, and it was really quite a pleasant function: Mrs. Preston especially, is a remarkably nice woman. Of course the usual questions about the political crisis in Ulster. 48 I must confess that I am getting tired of playing the journalist to every one I meet in England. One is always more or less on trial on such occasions and it is hard at a moment’s notice to make any adequate answer to such a wholesale question as ‘What do you think about the Ulster business?’ And the most difficult part is that you know that the people to whom you are talking are not really in sympathy with our party at all, but merely spying out the nakedness of the land.

The ordinary work of term ends this week and we begin the eternal nuisance of exams. I feel that they are really very inefficient tests of one’s knowledge, since I have often done very well on a subject that I have made a mess of in the term and vice versa. But, whatever their intrinsic worth, they are always very welcome as a signal of the end of term. I am glad to say I shall see you again, all being well, on Wednesday week. So will you please book the berth for the night of Tuesday week. I hear you will have W. home this week, so we shall all be together again.

Hoping that you are a good deal better,

I remain,

your loving

son Jack

Lewis was so unhappy at Malvern that his father agreed he should leave at the end of July 1914. On 19 September 1914 he arrived at Great Bookham to be tutored by William T. Kirkpatrick.

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

Hillsboro, 49

Western Rd,

Headington

Jan. 24th 1926

My dear Barfield,

It was a kind, if uneconomic, thought to send a copy to a certain purchaser. 50 Many thanks. I have now read it through. Prior to any other criticism, you will be glad to know that I found it all interesting and enjoyable, I was nowhere inclined to skip, or anxious to get on to the next chapter. In other words it fulfils the first elementary condition of a good book: the basis without which higher merits are of no avail. It is completely and certainly readable.

Perfect clearness, at a first reading, I cannot claim for it: but this was hardly to be expected. I shall be able to say more about this when I have read it again. I don’t mean, of course, any serious ambiguity or culpable difficulty: certainly no obscurity in any particular passage–only the parts are much clearer than the whole. By the bye, a good deal of this may be due to my knowing more about your outlook than I have (quâ reader) a right to know, and getting muddled because I am always trying to link up your statements with that background: almost all of it may be due to that. Or perhaps I want to end up with a unity (of mental growth) which the knowledge we possess does not really admit. In a way, too, this slight inconclusiveness or ‘higgle-de-piggledyosity’ of one’s final impression, is not a drawback: it leaves me very anxious to go further: and possibly this power of suggestion has to be purchased by some little weakening of statement.

Suggestive it is nearly everywhere. No one can fail to get the feeling you had when you wrote it or feel windows opening in all directions. You have quite definitely succeeded in that way. The occasional levities (so dangerous) have all ‘come off’: specially the one about ‘the oldest and safest of human occupations’. 51 The passage about early Christianity and the significance of persecution is admirable, and perhaps the best ‘episode’ (epic sense) in the book. The advance of the Aryans was well done, too, but we all expected it to be. Of course I disagree with your account of Plato and Aristotle and may have to explode it in a footnote some day, but there’s no good thinking about that now. ‘I said it very loud and clear, I went and shouted in your ear’ 52hellip;and you wouldn’t listen– . 53

. 53

I have seen only one review (a good one) in The Observer, 54 but you probably have them all thro your agency. Dymer55 goes to the typist this week. Kindest regards to Mrs. Barfield.

Yours

C. S. Lewis

TO WILLIAM FORCE STEAD (W):56

Hillsboro

[1926]

Dear Stead–

I found your gallies this afternoon when I went into College and have just finished reading the book. 57 I have been forced to deal with it more hastily than I should wish and I feel in many ways incompetent to deal with it.

There is first the temperamental difference: and then the difficulty of a literary method which I have never practiced and have hardly studied at all. I hardly know by what canons to judge this sort of loosely connected and highly subjective mixture of anecdote and description: I don’t care for it as done by Yeats & others and yours seems to me about as good as theirs. I am afraid this will seem less a compliment than a testimony to my utter incompetence.

I am much more interested in the philosophical part: it seems a very good gathering together in a popular form of several of the more wholesome trends of contemporary thought. It was a pity that determinism had to come in: because on the popular level both ‘determinism’ and ‘free will’ are nonsense, aren’t they, and both really the same in the end. But you couldn’t help that. 58

I am more worried by an apparent inconsistency wh. you seem to remain in–like most of us. On the one hand the spirit is (to you) out of time: on the other, evolution in time is (to you) a thing of real spiritual significance. You say, indeed, that the spirit itself does not evolve, and I’m glad you do. But I don’t feel that you have done very much towards reconciling the timelessness of the spirit with the value of its apparent adventures in time. Mind, I don’t say they are incompatible, only that you have not reconciled them.

Again, in your pantheistic conclusion, should you not show that you are aware of some of the moral difficulties? I mean, if the spirit grows in the grass etc, and in the cancer and the murderer, if it does everything, must it not be simply the neutral background of good and evil? 59 Of course if you held that the spirit was in time you might make some play with the notion that the bad processes represented less developed grades of her activity–but you are debarred from that. I take it your spirit has no history. However, we all end in difficulties. On this side I think the book will be useful as a channel by which the Bergsonian evolutionism and idealistic metaphysic (even if you have rather tied them up in a bag together than fused them) may reach the weaker brethren and protect them against ‘astronomical intimidation’. 60

Thinking it over again tho’, I am a little startled at the various ingredients of the cordial you are giving them: Bergson, Croce, 61 Roman Catholicism-up-to-a-point, and ‘High Thoughtism’ as represented by Coué. 62 But I daresay it’s alright.

As to the narrative and descriptive passages with wh. you sweeten discourse, I can’t say much. I don’t understand this method, as I said, and can only humbly warn you of the dangers. It is dreadfully hard to convince a reader (tho’ of course your personal assurance would convince me as a man) that you kept on feeling appropriate and significant things at the rightful places. If a malignant reviewer wrote

‘Who is the happy tourist, who is he

That every globe-trotter would wish to be’,

could you defend yourself? Don’t be offended: I am not saying that: but I feel you are on terribly thin ice in Notre Dame, at Lourdes and at St. Peters’

The only particular (i.e. the only useful) criticisms I have to offer, are these

1. I shd. like all the passages about ‘this age’ or ‘our own time’ excised. Don’t sneer at contemporary thought, when your great merit is to be a representative of some of its most characteristic tendencies. Particularize on contemporary vices and follies if you like: but don’t talk as if you were ‘born out of due time‘63 while you are writing a book that couldn’t have been written except in the C 20th.

2. I shd. like the passage about the French kings cut out. I suggest that it is merely a re-emergence of something you legitimately felt at sixteen: at your age, talking about serious subjects, it only awakens distrust and alienates the reader.

3. Your barque on Oxford canal I can’t accept. Once again, if as a man, you tell me this happened, far be it from me to give you the lie in the throat. But if as an artist you tell me as reader that you arrived independently at the argument of the Kantian deduction of the categories, all in a flash, because someone asked you the time–incredulus odi. 64

Please neglect anything wh. I have said if it is based on misunder standing. So much for the book on the higher level, as a serious bit of thinking. On the65

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

Hillsboro,

Western Rd,

Headington,

Oxford

[April 1926]

Dear Barfield,

Oh heavenly! I’ve no business to come and it means leaving in the lurch a brother who will be here, but damn it, this once, come what may–I’m going to take a moral holiday and come.

From 9th April (i.e. arriving at rendezvous on evening of 8th I hope) to the 11th, (i.e. leaving you on Monday) will be the best I can do. 66 From the 2nd–4th wd. be much better for me, but I suppose you can’t manage that? I vote for Newbury etc. as against the Cotswolds–and the more Savernake you can put into it the better.

I have ‘puffed’ your work in a lecture. Dymer has been accepted by Dents. Said it gave them ‘extraordinary pleasure’. Let me know about all arrangements as soon as possible.

Yrs

C. S. Lewis

TO WILLIAM FORCE STEAD (W):

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

Wednesday

[9 June 1926]

Dear Stead

Thank you very much for the book. 67 Your publishers deserve a word of thanks for something which will make such a handsome addition to my shelves. I have not, of course, had time to read it through again, but I have looked at some of the poems which, pursuing the argument, I rather neglected when you showed me the proofs. I think Thames Valley in Winter68 and the Graveyard Among Mountains69 are my favourites, tho’ the blank verse Ponte Santa Trinita70 ends with a very fine image. 71 Perhaps it is only my home-staying ignorance that guides my preferences to those that deal with England or (as in the Graveyard) with things that everyone can imagine in his own terms.

I will certainly do what little I can for the book but there are very few among my friends who are not either too hard up to buy any new books except by those who are already their favourite authors, or too utterly remote from your point of view to come within skirmishing distance. I enclose a parody which I am thinking of sending as a leg pull to T. S. Elliot’s paper. 72 Please let me know if it would do. Yours, with very many thanks & best wishes for success

C.S.L.

P.S. Please return the enclosed, after judgment, and don’t give me away.

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

Hillsboro,

Western Rd,

Headington

24th Aug. 1926

My dear Barfield,

This is splendid. I shall be free on Thursday (probably) and after Thursday (certainly). If, as I suppose, you are both at Long Crendon73 we all hope you will both come over and lunch and tea here. Choose your day and let us know. If you are alone, come alone.

Harwood first told me of Mrs. Dewey’s74 death–you know I don’t read the papers. Please tell your wife how sorry I am. One says that the death of the old is no tragedy and so on, but I fancy they were great friends, more than parents and children usually are. It must have been a nasty knock.

We have had a wonderful walk beyond the end of the known world. I have seen the baby and met the omniscient baron. It will be delightful to see you: on top of the walk it seems almost more luck than I can digest.

Yrs

C. S. Lewis

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

Sept. 15th [1926]

My dear Barfield,

The meet will be at Beckley pub–the one at the bottom of the hill–on Friday next at 1.0. p.m. 75 You had better pick me up at Hillsboro in the morning and we can go to the rendez-vous together. Please notify. The passage re cats was ‘They say I rub their fur the wrong way, but I say why can’t the cats turn round.’ 76

As for that feeling of not being a great man always remember

1. Guid sheltrom is in humilitie77

2. Even so, all language etc.

Yrs

C.S.L.

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

Magdalen

[October 1926]

My dear Barfield–

How tiresome about the letter. I had trusted to acquire fame by it. The chief points were;–

(a) That this is, so far, a great poem78–in the unequivocal sense–the sense which those words ordinarily bear in literary criticism. It challenges comparison with the Prelude, 79 and keeps its end up. I think spiritually it is not as high as the Prelude (it does not cover so large nor so momentous an experience): on the other hand it is more consistently poetical. I noted only one passage where you came near prose. ‘Trivial reasoning won his grave assent Provided only its conclusion mocked etc’. I have no doubt at all that you are engaged in writing one of the really great poems of the world. All this was accompanied in the letter with all sorts of devices to convince you that I really meant what I was saying: but I can’t bother to do them all again and you’ll have to take it neat. Of course I know I am saying a v. big thing, and one can’t be sure that I am not mistaken.

(b) What I particularly admired–what makes it unique–is the success with which you have combined res olim dissociabiles. 80 You have contrived to keep all the time within the labyrinthine fidgety world of the inner mind, and yet not lost the soaring, winged movement–the cantabile, as of Milton or Marlowe. I don’t know anything else where this is so fully attained. The whole of the love section, the change from sunrise to noon (no more singing Osirian secrets), the climax at ‘not climbing in But falling out: henceforth seek earth on earth, Heaven in heaven’, and the finale about personal passion like a creature that lives after its back is broken–all this is wonderful in its songfulness maintained thro’ philosophical matter. That section alone puts you, for me, among the very great people. But indeed you gave me the authentic thrill all over the place. There are things I shall never get out of my head: such as ‘If discs of gold should lie, Never so far between, along the floor Of that infernal pilgrimage’–‘His soul in him like a seagull’s cry’–‘Nailed stoutly to the hopes of little joys’–‘Their mineral passion’.

(c) Two parts as a whole seem inferior. The first is the opening section. I can’t feel you have entirely solved the problem of dealing with emotions at once primitive and reticent without being mawkish. Need the man think of his child (whether born or unborn) primarily as ‘my image’? Again it opens with a picture–the sky etc. Pictures (I mean the more completely picturable kind of image) are not really your long suit: and this, with its aureole etc. remains to me literary and uninteresting. And the fact that it is a leitmotif wh. has to reappear in a later section makes it more unfortunate. I should advise a complete breaking up and rewriting of this section with the powers you now have. The next is (I am sorry to say) the peqipéseia81 of the whole poem: his enlightenment in the reading room of the B.M. 82 The first paragraph about there being no Eureka cry but ‘Sun Turns himself over’ is excellent. So is the third about the man who ‘moves about Within the quiddity of light and sees Seeing itself, and that our eyes are veils Not windows’. But just in between those the thing itself has to come–and it doesn’t. The old and not v. profound image of the light in a dark cave is inadequate. You see, the discovery that consciousness is a voyage of exploration, on the purely logical level, needn’t lead to any spiritual consequences at all. Apparently it meant something to that man at that moment wh. it needn’t mean universally to any philologist who happens to agree with it. That something you have, I am afraid, just left out. This sounds extremely disappointing, I know: and I have no idea what you can do. Some really living metaphor or simile–something suggestive and mythopoeic, still hovering just outside your consciousness, must come in here and flood the thing with light. You had better fast and pray.

After this week I shall be in College, and of course delighted to see you. I can put you up for a night but I am afraid our monastic system will not allow your lady wife. Let me know what day you think of coming. Dymer is out about three weeks. I have had no good reviews yet, but a letter from l’Anton Fausset saying that he has reviewed it for the T.L.S. and as the review may not be printed for some weeks he thought he would write and tell me etc. He is v. eulogistic. 83 So is Quiller Couch (whose opinion, between ourselves, is valueless) in a letter to Dents. I suppose you are too much out of the journalistic world to help me now? Hoping to hear from you about your visit,

Yrs

C. S. Lewis

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

Feb. 2nd 1927.

My dear Barfield–

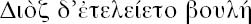

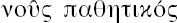

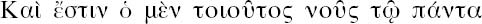

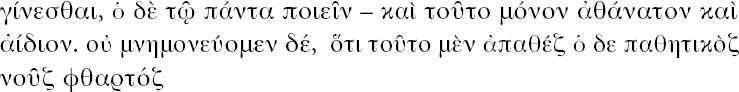

Advice wanted urgently. Do you know anything of a thing called the Panton Arts Club? They want me to join over the head of Dymer. Now ten to one this is merely a catchpenny stunt for gulls. On the other hand they say they allow only 100 members in the literary section, admitted on the value of work published. So it may, for all I know, be a real honour. If you know or can find out which it is, please send me a line as soon as possible. I have been having a heavenly time since–the bogies are in full retreat and I have been almost dizzy with real joy several times a day. In fact, a sort of remarriage of the Spirit. I have also got the poetic and the other mind settled now. It all comes in Aristotle De Anima III v. 2. There are two elements the  84 and the

84 and the  . 85

. 85

. 86

. 86

Yrs

C. S. Lewis

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

Hillsboro.

Sept. 10th [1927]

My dear Barfield–

I have finished a first re-reading of the Tower. The great passages–VI, VII, X–stand absolutely where they did. The later cantos I have enjoyed much more than I did before: but of course this is chiefly due to my increased understanding of and sympathy with the matter.

As to the poem as a whole, I am afraid I feel now a rather serious break between the two periods of composition. Oddly enough it seems much shorter than I remembered, and much less of a ‘just’ narrative–more a series of impassioned lyrical monologues loosely connected by the identity of the hero. In fact it is only with the love affair that the unity begins. I don’t know how far you are thinking of ever working on it again. If you do, I shd. (reluctantly) chuck II, III and IV right out. V and the danceable duet wd. have to be saved: but I shd. like the bristles of mechanic thought etc. to come after the love-tragedy. I quite realize the reply that if they hadn’t been there before the tragedy wd. not have effected him as they did. But the masses of the design wd. be much better grouped if they emerged into consciousness only after it: one must simplify a bit or the reader gets the impression that wherever he opens the poem the hero will be always in some damned ‘situation’ or other, and gets into the ‘What is it this time’ state of mind. I shall read it again–some things I liked seem to have disappeared. (I don’t think it wd. be at all admirable to work it up into ‘just’ narrative. A few prose glosses at the beginnings of cantos, if really well written, wd. be admirable. In the text, I think a single week’s work could introduce a lot more clarity & make an enormous improvement).

Tolkien says ‘any day’ after the 13th–so reply fixing me as soon as possible. I read the Livingstone Lowes at a gulp–it is really excellent, including the scholia. It wd. have been worth reading for ‘Why don’t the cats turn round?’ alone. I have just read Edith Sitwell’s Sleeping Beauty. 87 Without any attempt to place her exactly, I say she is clearly one of the English poets in the general sense wh. includes Milton, Longfellow, Hood88 & Southey. 89 There’s no good denying it,

yrs

C.S.L.

At nihil eorum quae superscripsi prohibet quin constet inter ompnes humanam sermonem esse Orphicum carmen. 90

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

[1928]

You might like to know that when Tolkien dined with me the other night he said à-propos of something quite different that your conception of the ancient semantic unity91 had modified his whole outlook and that he was always just going to say something in a lecture when your conception stopped him in time ‘It is one of those things,’ he said ‘that when you’ve once seen it there are all sorts of things you can never say again.’ We went on to observe on the paradox that tho’ you knew much poetry and little philology the philological part of your book was much the sounder.

Jam and powder you see

C.S.L.

Beside the fact that Barfield’s literary works were not providing sufficient income, in 1929 his father, Arthur Barfield, lost the services of his brother in their London law office, Barfield & Barfield. Pressure was put on Owen to help, and after reading for a degree in law he moved with his wife to London where, for the next thirty years, he worked as a solicitor.

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

[1929]

My dear Barfield–

There’s one thing about your novel92–you do really succeed in producing the atmosphere of real conversation among young men of the thoughtful type–specially those revealing moments after the fire has gone out. I have never seen this or anything remotely like it in a novel. It is as if reality was actually thinking itself in the pages of the book. These are the best parts by miles.

I am more concerned than ever about John. He seems to me too improbable. His sensibilities are so dam fine that when he hears something he disapproves on the wireless he smacks the set. On the other hand they are so blunt that he hasn’t the vaguest glimmering how a woman like Margaret feels after being disappointed of motherhood, and supposes, in the conversation that reveals her agony, that she is considering his feelings. He is so keen on liberty that he writes your Ioldobaoth poem (your John could not have written it) and also so brutally tyrannical that in the same conversation he sweeps aside his wife’s claim to elementary spiritual privacy. His life is turned upside down by a ceremony with a candle–and he has almost forgotten the child a few days after the birth. He is so unselfish that he never stops talking about the fate of humanity: and he is so selfish that at the v. moment when the possibility of his wife’s death is brought before him, his reply to the suggestion that Gerald shd. take her away is ‘We shan’t have much time to talk.’ That this grumble should cross his mind at such a moment is bad enough, but intelligible. Peccavimus omnes. 93 But the man in whom it would not be strangled at birth–in whom it would reach the stage of words–is surely intolerable.

Then his mere behaviour! People who have been brought up as he has do not really violently shake their wives (shortly after childbirth) and smash the furniture–unless you mean him to be definitely in a nervous breakdown. Have you yourself ever met anyone who acted at all like this? And what value remains in the noble aspirations about the world in general when you have shown us his savage egoism towards those parts of the world wh. he is immediately in touch with? Surely the sort of character whose heart is always bleeding for Europe and who can’t reach even the forbearance of common civility towards his wife is more proper for bitter comedy (like Tartuffe)94 than for your novel?

Excuse haste, but I am really v. deeply bothered about this.

Yrs

C.S.L.

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

Oct. 21st 1929.

My dear Barfield

Thanks for letter. I wolfed Part IV of the novel with great excitement and must, of course, re-read it before my criticism can be of much value. What I think I can be pretty certain of is that it is thick strewn with evidences of real greatness and that (at least) Humphery, Janet and Gerald must remain in the mind of any fair reader as entirely original and living characters. Whether besides having greatness in it it is part of an actually great novel, I am not prepared to say: and the disjoined fashion in which I have read it wd. make it absurd for me to judge it as a whole.

On the bad side, as you probably feel itself, there is in this last part a problem you have not (I think) completely solved. You hold a belief about the world, invoking big secret powers in the background: most of your readers don’t. That in itself wouldn’t matter. Unfortunately, however, your readers are familiar with the use of secret & satanic societies as machines either in good semi-fantastic recreational fiction (e.g., Sard Harker)95 or in frankly commercial shockers. As a result the average reader will complain that Part IV transfers to a different convention what began as a v. serious naturalistic novel. Your problem was how to show that for you at any rate such things were on the same level of reality as ordinary London life. You have not completely failed, but I doubt if you have completely succeeded.

It is v. unfortunate that we are introduced to that side of the story by the device of unintentional eavesdropping–very usé and associated with fiction of quite a different type. It also depends on two improbabilities a. A moon light enough to read by, wh. is rare in England. b. A man who feels afraid lest a face shd. look in through the window & then immediately sits down to read in the window with his back to it–surely the last thing you’d do in that mood. I think these improbabilities in mere mechanism don’t as a rule matter much to anyone but professional critics: but they do matter when your whole difficulty is to persuade the reader that the scenes which they serve to introduce are as serious as the rest of the book. But perhaps this just has to be faced…I wonder could you have let it in more gradually, so that the reader found himself accepting it before he realised what he was in for? Perhaps when I read the whole I shall find that you have done this.

You understand that my criticism here is not concerned with the truth of these things. Assuming them true, remembering that they are already frequent in fiction of a certain type, how are you to convince readers–that is the whole question.

Long at lectures

On Monday morning

I work till one! Hoihe!!

Piddling pupils

I in taking am engaged!!

Can your car

So swiftly over

Earth’s back wander

From Oxford to London between one and 5.45?

Walawei! Hoo-ruddy-rah!!!!

Ho-hai!!!!!

!!

?!!!!

If so, call

For me at Magdalen

Were wisest rune

On Monday at one!

If you lie

On Tuesday night

In Magdalen’s ancient College

You will meet Dyson

Dining with me

Of men the justest!!

[The whole scene explodes]96

I’m afraid my car is no go. I feel so much pleasure that I doubt if it can be innocent

C.S.L.

TO A. M. DAVISON:97

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

Sept. 29th 1929

My dear Nurse Davison

Excuse me. I cannot address you by any other name. Remember you? I should think I do. Do you remember the night Warnie and I came home very late and got into trouble and were sent to bed without supper, and you brought us in bread and jam in our little room–opposite my father’s bedroom? Do you remember the night you went to the Mikado with Warnie and I wasn’t allowed to go? Do you remember the first night before my poor mother’s operation when you both sat and talked about operations and I said ‘Well you are gloomy people.’ And now it has all happened again with my father. I thought of you a lot during his illness and wished you could have been with him. He constantly mentioned you and your photo has been on the mantelpiece at Little Lea for a great many years.

Thank you for your sympathy. I thought I had perhaps got a bit used to people I cared for dying while I was at the front, but it doesn’t seem to make much difference. He was such a very strong personality and had been the background of my life for so long that I can hardly believe its all over. One keeps on thinking ‘I must tell him that’ when some little episode happens, and then [one] remembers. I suppose we get used to these changes in time. Thanks awfully for writing. It is really comforting to be taken back to those old days. The time during which you were with my mother–and I remember that much better than my own little operation–seemed very long to a child and you became part of home. We must try to meet when I’m in Ireland again. Probably we have often passed each other in the street without knowing.

Yours very sincerely

Jack Lewis

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

Jan 16th [1930]

My dear Barfield

(1) Thanks for letter: I can’t undertake correction alone, and as long as Ficino & Fichte are hanging over us we can’t send it to Blackwell.

(2) All our labour about  98 has been thrown away as that chump Harwood had never heard ‘King Stephen was a worthy peer. ‘99So much for the facile assumption that one’s friends have as much literature as oneself. However it is some consolation to know that he puzzled his head over the poem for several hours and could not construe it.

98 has been thrown away as that chump Harwood had never heard ‘King Stephen was a worthy peer. ‘99So much for the facile assumption that one’s friends have as much literature as oneself. However it is some consolation to know that he puzzled his head over the poem for several hours and could not construe it.

(3) Addendum:

Et Pterodactylium par nobile, parque draconem,

Et dinus saurus, dinaque saura sua.100

(4) ‘The imagination knows no proportion.’ Whose imagination?

(5) I got really bothered about your attack on Ogden & Richards. 101 Do you really mean that all thought is bound by the original ‘metaphors’ in the words? If so–Tantamne rem tam negligenter. 102 So as I had to write a paper for the Junior Linguistic I took this subject, and it has come out to the conclusion that in speaking of mogsa

103 the only alternatives area. To revive the buried ‘metaphors’. i.e. really to think of breath when you say spirit.

b. To invent conscious, new metaphors all the time. c. To talk without meaning. (6) I have had a cut at Jacob Boehme. 104 Chapter II of the Signatura Rerum is the most serious attempt ever to show the Many coming out of the One. Unfortunately I can’t understand it. I don’t like it entirely. But we must worry it out. You can buy it in Everyman and had better get to work at once. 105 Love to all, and respects to any who won’t have love–such as Sandy & Basil. 106

Yrs

C. S. Lewis

When Albert Lewis died on 25 September 1929, Warnie was in China and did not return to England until 16 April 1930. This left Jack to deal with the contents of the family home, ‘Little Lea’, in Belfast. Jack wrote to Warnie on 12 January 1930 that their aunt, Mary Tegart Lewis (1868–1941), had heard that Little Lea was to be sold and

that she supposed I knew about the two book cases of Uncle Joe’s that P. has ‘stored’ for me: that she very much wanted to have them: could she send and have them taken away at once…The minute I read it I knew in my bones that it was our little end room bookcases. I replied: that I should certainly not hold a sale without giving my relations the chance of mentioning to me any articles which did not belong to you and me…but that I should very much prefer not to start dismembering the house before you returned.107

In the end, the bookcases were overlooked, and were shipped to Oxford with other items from Little Lea.

TO JOSEPH TEGART LEWIS (P):108

Hillsboro,

Western Rd.,

Headington,

Oxford.

[January 1930]

My dear Ted

We were considerably dismayed at the arrival of the two bookcases on this side, which was the result of a misunderstanding of our orders. The cost of returning them was rather a poser: and since our own library is already overflowing, this charge would have to be followed immediately by a further outlay of two new bookcases.

Consequently, since hearing from Condlin109 that they are wanted for your own house and not for Sandycroft, 110 we have been wondering whether we could not come to some less costly arrangement that might suit equally well. We understand that you owe us (i.e. my Father’s estate) some money. Would you feel disposed to cry quits with us over that and the bookcases? I need hardly say that if we thought the real market value of the bookcases equal, or nearly equal, to the money, we should not make such a proposal: for we very gratefully and gladly acknowledge our heavy debt to you, in another kind, for all your goodness last summer. 111 Let me take this opportunity of thanking you on Warnie’s behalf and my own. I should be glad if you would let me know, as the Americans say, your ‘reactions’ to this idea.

Please give our love to Aunt Mary and to all our cousins of all generations. I hope that your wife and you are keeping well. The fair librarian, no doubt, has long since outgrown both me and her last year’s library–things change so quickly at that age. If not, give her my profoundest salaams. Wretched weather here and plenty of work.

Yours ever

Jack Lewis

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

[April 1930]

No–to-morrow would be a bad day–a most inconvenient, footling, scarcely possible occasion–for a walk. But I could manage Saturday if you could come then. In the meantime may I tender ‘brief thanksgiving’ for your labours–rather say your father’s labours–in the matter of the mortgage.

Hope my walking stick is proving in your walks a good companion, serving (though indeed you stole it–boned it, bagged it, scrounged it, stole it) serving as a stout reminder of the beautiful Quirinal painted like the vault of heaven and the lovely derivation and the history semantic and the long phonetic story of the mystic word caboodle–Dum-de Dum-de Dum-de Lewis. 112

TO T. S. ELIOT (P):113

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

May 21st 1930

Dear Sir

I am requested by the Michaelmas Club of this College–a society for literary, philosophical and political discussion–to invite you to read a paper before it this term. Any date which you choose before June 5th we will endeavour to conform to: and we hope that, in spite of such short notice, this may make it possible for you to come.

If you are able to do so, it will give me great pleasure if you will dine with me in hall before the meeting and be my guest in College for the night.

Yours faithfully

C. S. Lewis

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

June 18th 1930

My dear Barfield,

I approach you with some fear. Last week Griffiths spent a night with me and, of course, asked about you. I told him that you were thinking of editing Coleridge. As Griffiths has recently been turned inside out by Coleridge he was naturally very interested and hoped very much that it would materialise. Now comes the occasion of my fear. I said that the scheme depended partly on endowment by an American University, and that if that failed you would probably seek more remunerative employment. 114

Was this a breach of confidence? The trouble is that what follows makes the whole conversation so much more important than it seemed at the time. I very much hope that you will not think I deserve to be ‘avoided as a blab’: ‘the mark of fool set on my front‘115 I can face with more composure. At the time, in its context, it seemed a harmless thing to say–but I suppose that is what blabs all feel after the event. If you think I was wrong, I can only offer an ad misericordiam116 appeal for pardon.

Anyway, in a few days, came the enclosed, which you will deal with as you think fit. What ever view you take of my action, I hope you will feel as I do at discovering the race of Calverts is not extinct. A third of £800 a year is not an income wh. most men wd. feel moral scruples about.

I shall be extremely anxious till I hear from you.

Yours

C. S. Lewis

P.S. I suppose you got Death with covering letter? 117

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

[1930]

My dear Barfield,

If you don’t know it already I think this will interest you. Had you, like me, always been struck with the oddity of the Greeks having a craft-conception for ‘raw material’ ( , forest > timber > what you make things of) whereas the Latins have what seems a vital one–materies? Well, apparently, the claims of materies to vitalism are v. shaky: for the possibilities are

, forest > timber > what you make things of) whereas the Latins have what seems a vital one–materies? Well, apparently, the claims of materies to vitalism are v. shaky: for the possibilities are

(a.) That it is older ‘Dmater’ <  –to build, make

–to build, make

(b.) If from mater, then according to one school (which seems incredible) mater itself is not vital. For if it comes from m (v. Monier Williams Sanskrit Lexicon)118 m

(v. Monier Williams Sanskrit Lexicon)118 m means to measure > to divide up > to prepare > to make. Thence m

means to measure > to divide up > to prepare > to make. Thence m tri (nomen agentis) = measurer (and as such a name for the moon) also maker. J

tri (nomen agentis) = measurer (and as such a name for the moon) also maker. J -m

-m tri = offspring maker, hence merely m

tri = offspring maker, hence merely m tri, mother. It wd. be v. strange if a fact like mother had so early been given an ahrimanic twist. Another school refuses to connect m

tri, mother. It wd. be v. strange if a fact like mother had so early been given an ahrimanic twist. Another school refuses to connect m tri with m

tri with m at all (but then what do they make of m

at all (but then what do they make of m tri = moon?). J.A. thinks the-tri is not nomen agentis at all but the mark of one-of-a-pair, as in

tri = moon?). J.A. thinks the-tri is not nomen agentis at all but the mark of one-of-a-pair, as in  ,119 other etc. As Humpty-Dumpty says, there’s glory for you.

,119 other etc. As Humpty-Dumpty says, there’s glory for you.

Yrs

C.S.L.

TO OWEN BARFIELD (W):

[1930]

My dear Barfield

Alas!–I’m in bed: so our meeting will have to be put off. What about Friday week?–or next Wednesday? Please let me know. The Essay was terrifically exciting & really fine in places, but I think needs a little more dovetailing & riveting–some of the transitions of thought are not at all easy.

This present trouble is only a bad cold with temperature. In spirit I’m on the pig’s back & am trying to read the Hymns to the Night. 120 What on earth is the meaning of ‘riss das Band der Geburt des Lichtes Fessel’. 121 The Crab couplet is fine. I’m glad you liked the lyric.

What with one thing and another I feel the earth might go up in sky rockets any moment. The bit about Schlaf gegentritting out of alten Geschichten in the article of himmelöffning struck me–as you may imagine. 122 But I don’t fully understand all your (& Novalis) view about Sleep–I remember your poem long ago about the Sister.

About the Essay–don’t think it has failed either per se or in its effect on me. It is bathed in a golden cloud & drips with honey–well worth doing a good bit more on. Damn it all you can’t utter things that have been kept hid from the foundation in a parenthesis. But I often feel that having a talk with you is not like going up in a balloon but like trying to hold a captive balloon.

I’ve re-read Middlemarch.

yrs

C. S. Lewis

Isn’t it ex vi termini123 not vi termini? Where does that remark from Pythagoras come from? (Ans: from Pythagoras. Ans: Ass!)

TO T. S. ELIOT (P):

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

April 19th 1931

Dear Sir

It is now some six months since I submitted to you the MS of an article entitled ‘The Personal Heresy in Criticism’. 124 In this article I contended that poetry never was nor could be the ‘expression of a personality’ save per accidens, and I advanced a formal proof of the position. As I believed that you had some sympathy with the contention, and that, though often asserted, it had not before been proved, I had anticipated a fairly early reply. I supposed that if the proof seemed to you invalid you would immediately reject the paper: if it seemed valid, you would think it worth publishing. I still think that your decision on such a purely argumentative piece of work would be a matter of very little time, if once you read it: and as my MS has never yet been acknowledged, accepted, or rejected, I conclude that it has–no doubt very naturally and venially–been submerged in the inevitable silt of a busy office. I hope it will not strike you as an impatience if I now remind you of it. I do not–naturally–wish by any pressure on you to reduce my own chances of reaching a public on a subject about which current views exasperated me beyond bearing: but equally naturally I should welcome a decision of some sort in the near future.

Yours sincerely

C. S. Lewis

P. S. Owen Barfield offered some time ago to remind you of the MS, but we decided to try the effect of more waiting–with the result of my present letter!

TO T. S. ELIOT (P):

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

June 2nd 1931

Dear Sir

Thank you for your letter. My own position is as follows: I have very little doubt that I could get my essay printed in some much more academic publication, but as, in such a publication, it would be merely entombed, I prefer to reach the periodical public, and I do not know of any audience more likely to be affected by it than that of the Criterion. I should therefore have no objection to waiting nine months: what I should like to be more assured of is the prospect I have at the end of the nine months. I do not mean that it would be reasonable for you to bind yourself to accept, at that time, an article which you may not by then clearly remember, and about which you may legitimately change your mind. In other words I am quite prepared for the risk of your ‘corrected impressions’. What I am less ready to be at the mercy of is the mere richness or poverty of suitable contributions–the fulness or emptiness of your drawer–nine months hence, which nobody can predict. That is, if you will keep a place for it (subject, of course, to special emergencies) I am quite prepared to wait and to abide by your second, and unfettered, decision as to my suitability to fill that place. Perhaps you would let me hear from you on the subject. 125 The essay does, as you have divined, form the first of a series of which I have all the materials to hand. 1 The others would be

2. Objective Standards of Literary merit.

3. Literature and Virtue (This is not a stylistic variant of ‘Art & Morality’: that is my whole point).

4. Literature and Knowledge 5. Metaphor and Truth

The whole, when completed, would form a frontal attack on Crocean aesthetics and state a neo-Aristotelian theory of literature (not of Art, about which I say nothing) which inter alia will re-affirm the romantic doctrine of imagination as a truth-bearing faculty, though not quite as the romantics understood it.

I am sorry to burden you with another letter to answer

yours faithfully

C. S. Lewis

(1) It is mainly a question of giving them a less technically philosophical form.

TO MARY SHELLEY (T):126

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

June 18th [1931]

Dear Miss Shelley

Yes, rather. When I got the letter from Miss Seaton127 I did not know that the pupil mentioned was the Dysonian one–nor, I think, did Mr Dyson mention your name when he spoke about you to me.

Now as to work. If you are staying up over the week end and could call on me on Saturday morning we could discuss this. If this is impossible my present advice is;–

Doing Chaucer and Shakespeare in the same term seems to me a hazardous experiment, unless there is some special reason which I don’t yet know. Our usual plan here is to spend a term on Chaucer and his contemporaries.

As regards reading for the Vac, my general view is that the Vac. should be given chiefly to reading the actual literary texts, without much attention to problems, getting thoroughly familiar with stories, situation, and style, and so having all the data for aesthetic judgement ready: then the term can be kept for more scholarly reading. Thus, if you were doing Chaucer and contemporaries next term I shd. advise you to read Chaucer himself, Langland (if you can get Skeat’s Edtn: 128 the selection is not much good) Gower (again Macaulay’s big edtn if possible, not so that you may read every word of the Confessio but so that you may select yourself–not forgetting the end wh. is one of the best bits)129 Gawain (Tolkien & Gordon Edtn)130 Sisam’s XIVth Century Prose & Verse (all the pieces of any literary significance). 131 If you can borrow Ritson’s Metrical Romances, 132 so much the better.

But perhaps you have read all these before. If so, and if there are other special circumstances, we must try to meet. If Saturday is impossible ring me up on Friday and I will squeeze in a time somehow or other.

It is I who shd. apologise for my muddle rather than you for your ‘importunity’–the latter, being in any case, the more flattering offence. I shd. be obliged if you would explain all to Miss Seaton. The (unnamed) ‘Dysonian’ pupil was one of the people I was leaving room for by my refusal to take ‘a pupil’ from her. In fact you were being crowded out by yourself among other people.

Yours sincerely

C. S. Lewis

TO HIS BROTHER (BOD):133

Magdalen College,

Oxford

Oct. 26th 1931

My dear Warnie

With regard to the Transfer to ourselves of the mortgage on ‘The Kilns’ which Mrs. Moore executed on October 2nd, this confirms our verbal agreement that in spite of anything to the contrary that may seemed to be implied thereby, your interest in the said mortgage is of the value of £500 and my interest is of the value of £1000.

Yours

Jack

TO EDMUND BLUNDEN (TEX):134

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

[1933]

Dear Blunden–

Thank you for your kind note. 135 I am particularly gratified at your liking that poem for, though it is not my own favourite, you are the first reader to notice at all! Dents agreed with you about the title being bad, and no doubt it is: but as the periodical press on which alone sales depend is managed entirely by Mr. Sensible and young Mr. Halfways between them, I don’t think a mere trifle like a title will interfere with my success. There are some things (Icelandic snakes, for example) beyond the reach of interference.

What do you think of the possibilities of my new kind of alexandrine without a break in the middle (see p. 253 etc)? 136 I don’t mean what do you think of the poems written in it: but (a.) Does it seem to you to be verse at all? (b.) Do you think it wd. be a good metre for translating Virgil. Don’t bother to reply–we can discuss it when we meet.

Yours

C. S. Lewis

Thanks. I have made a date with ‘little Musgrove’

C.S.L.

TO EDMUND BLUNDEN (P):

The Kilns,

Headington Quarry,

Oxford.

March 26th 1935

Dear Blunden

The examiner sits into Quarrie

Using the blude-red ink

‘Now who ill tae fair Edinboro’ gae

A’ o’er the text to swink?’

Then up and spake child Blunden

Ane harper guid was he

‘Oh I ill tae fair Edinboro’ goe

Those manuscripts to see‘137

But perhaps this is optimistic. But short of going to see the MSS, I agree there is nothing to do yet.

Yours

C. S. Lewis

TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES LITERARY SUPPLEMENT:138

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

Sir,–

Every student must have read with delight those opening pages of Dr. J. Dover Wilson’s ‘Manuscript of Hamlet’ 139 in which the author drives us back from the temptation of immediate tinkering with the texts to more and more fundamental problems in bibliography. We have hardly had in modern times a more beautiful example of what might be called  . 140 It is no criticism, it is rather a eulogy, of this process to follow the impetus thus given, and to ask whether we can stop even where Dr. Wilson stops. It appears to me that we ought to raise an even more abstract question which is prior to all the bibliographical questions. What do we mean by the genuine texts of an Elizabethan play?

. 140 It is no criticism, it is rather a eulogy, of this process to follow the impetus thus given, and to ask whether we can stop even where Dr. Wilson stops. It appears to me that we ought to raise an even more abstract question which is prior to all the bibliographical questions. What do we mean by the genuine texts of an Elizabethan play?

When the author defines his ‘main purpose’ as being ‘to recover Shakespeare’s manuscript’ (Vol. I, p. 51) no such question need arise; for this remains a legitimate object whether we regard the playwright’s manuscript as the genuine text or not: but we have the whole question on our hands when he says (p. 5) that the genuine text is that which corresponds with ‘what Shakespeare intended to write.’

It will be allowed that the meaning of ‘genuine text’ varies according to the kind of work under discussion. Thus the genuine text of ‘Paradise Lost’ is certainly ‘what Milton intended to write,’ for we know that Milton’s intention was to write a new poem of which he was the sole author. The genuine text of a traditional ballad, however, means something quite different; for here we cannot be certain that any individual ever intended to ‘write’ a poem for which he would be exclusively responsible, and if there has been a succession of authors, the lines made by the last are just as ‘genuine’ as those made by the first: nothing, in fact, is ‘corruption’ except errors of transcription and printing. I submit, therefore, that we do not know what we mean by the genuine text of Hamlet until we have decided between the two following alternatives. Did Shakespeare primarily ‘intend’ to ‘write’ a dramatic poem, or did he ‘intend’ to ‘write’ to take part in the composite activity of producing a play–i.e., a show? In other words, was the end which he set before him a book (for which he would be solely responsible) or a show (for which he would necessarily share responsibility with actors, ‘producer,’ manager, prompt man, musicians and even audience)?

Now Dr. Dover Wilson, as it seems to me, has answered this question quite clearly. He tells us (on p. 9) that Shakespeare ‘always thought in terms of the stage and never so far as we know contemplated any other kind of publication for his plays than that which stage performance gives.’ If this is admitted, it follows that Shakespeare’s manuscript, so far from being the genuine text, is, so to speak, an ‘ante-text,’ an embryo: one of the elements (though doubtless the most important) out of which, when it has been combined with others and modified to any extent that may prove necessary, the play or show will be made. It is, as Dr. Dover Wilson says on Chapter 1, a ‘draft.’

If that is so, we must be very critical in our reading of such a statement as the following: ‘Mommsen demonstrates that the FI141 Hamlet displays unmistakable signs of having been deformed and contaminated by playhouse influences, that it contains a number of small verbal additions made by the actors, that it has been moulded throughout to suit the purposes of some particular theatre.’ The danger here is lest we should treat everything whereby the concrete performance differs from the playwright’s ‘draft’ as ‘contamination’: for, on the view which has been expressed above, the concrete performance is the play, and it no more ‘contaminates’ the draft than birth ‘contaminates’ a baby. The real question is which peculiarities (if any) of the prompt-book version can be called corruptions.

Certainly not those peculiarities which fit it to ‘some particular theatre.’ If Dr. Dover Wilson is right in his picture of Shakespeare at work (Chapter 2), then we may assume that Shakespeare never had any end in view except performance in a particular theatre. If he intended such performance, he must also have intended such performance to be possible; he must therefore, in general, have intended such modifications of the draft as would render it possible, however much he may have neglected the detail of those conditions in the heat of composition. And this would seem to apply, if we follow Dr. Dover Wilson, not only to the reduction of man power but even to the straightening out of verbal tangles. ‘Shakespeare,’ he well says, ‘probably troubled his head very little about his tangles. If he remembered them, he might go back and straighten them out himself; if not, there was always the prompter to clean up after him, and it was part of his job to do so’ (page 24, italics mine). The process here described is plainly not corruption but delegation; and every such cleaning up by the prompter, unless it can be shown that Shakespeare explicitly rejected it, surely becomes part of the ‘genuine text.’ The actors’ additions are really in the same position. Shakespeare intended performance, and not even performance simpliciter but performance by these actors: the detail of their treatment he could not fully foresee, but toleration (or, for all we know, approval) of their interpretation in general must have been implicit from the moment he put pen to paper. We have no evidence that would entitle us to say ‘If Burbage groaned in his death scene, the groan was a corruption.’

It would be tempting to say that those modifications which Shakespeare himself first thought of are genuine, while those suggested by any other member of his company are spurious. But such a criterion would be arbitrary. Shakespeare produces a ‘draft’ which is too long. If he and another experienced man (or three others) look it over, surely the places for cuts will be fairly obvious, and it is largely a matter of chance who first condemns a given passage. The ‘genuineness’ or ‘spuriousness’ cannot depend on the accident. We cannot even say that those changes which Shakespeare agreed to reluctantly (supposing we can identify them) are corruptions: no man, perhaps, ever finishes a work of art without omitting much that he would gladly have retained, nor does the knife always hurt less in the author’s own hand than in another’s.

The conclusion would seem to be that we must do one of two things. We must either reject the conception of a Shakespeare who ‘thought in terms of the stage’ and replace it with that of a literary author to whom performance was as accidental as to Milton or Tennyson: or we must define the ‘genuine text’ to be ‘the whole performance in so far as Shakespeare did not explicitly disclaim it.’ If we do the first, then the manuscript is the genuine text: if we do the second, we must cease to talk of theatrical ‘contamination’: we must start with the assumption that the prompt-book is genuine, and the onus will lie on anyone who says that it is corrupt. I need not add that I am not attempting to criticize Dr. Dover Wilson’s history of the text–a task which gratitude and discretion equally forbid–but to criticize a fundamental assumption which he sometimes countenances and sometimes implicitly rejects, as is natural in a writer intent on much more difficult and concrete problems.

Yours,

C. S. Lewis

TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES LITERARY SUPPLEMENT:142

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

Sir,–

Dr. Dover Wilson in his kind notice of my letter has really settled the question. If the identity of the genuine text is a problem that ‘can only be decided on aesthetic grounds’–that is, on what Dr. Dover Wilson calls ‘no other principle than that furnished by the good taste and judgement of the editor’ (Manuscript of Hamlet, Vol. I, p. 7)–then we are thrown back here, as in other departments of thought, on the testimony of the uqó milof. 143 And that is a role which no one, least of all myself, will dispute Dr. Wilson’s right to fill. My own concern in the matter is not the defence of F, but the (implicit) defence of certain private propositions about literary theory which need not be stated here. I embrace gladly the doctrine that the ‘genuine text’ can be identified with the (aesthetically) best text; and my satisfaction would be complete if I felt sure that Dr. Dover Wilson would agree to two corollaries:–

(a) That the methods of the bibliographical school, of which he is such a distinguished member, are primarily useful not for finding the genuine text (which can be found only by taste), but for other purposes: e.g., dating?

(b) That certain excellent emendations (such as et tua conjunx or a’ babbled of green fields)144 are parts of the genuine text in virtue of their aesthetic merits whether Virgil and Shakespeare wrote them or not.

The second corollary may seem audacious; but I think it can be avoided only by the following distinguo: ‘Best text does not equal genuine text, but best is presumptive evidence of genuine.’ But this conceals the premises, ‘The author always wrote the best’–a proposition which is neither certain nor probable and which, in its negative application, will force us upon the methods of Pope, who ‘by a very compendious criticism’ (says Johnson) ‘rejected whatever he disliked. ‘145

I am, Sir, yours,

C. S. Lewis

TO ELIZABETH HOLMES (P):

Magdalen College,

Oxford.

Nov 6th 1936

Dear Miss Holmes

I have already ordered your book146 and should have done so before but for an inability to read the Lit. Sup147 (once my delight) which–with increasing baldness and a double chin–is the most distressing symptom of vanished youth. If I have any comments at all likely to be helpful after reading it, I shall take the liberty of writing.

Yours sincerely

C. S. Lewis

TO ELIZABETH HOLMES (P):

Magdalen

Nov 10th [1936]

Dear Miss Holmes–

Well: I have now read Margaret, all with interest and a good deal with keen enjoyment. It does not, I think, begin well. The death of the brother on p. 4–unless I have missed the point–has no poetical significance, being one of those things which would be important in a real biography only because it was true, & is therefore otiose in a poem.

On the bottom of p. 6 and the top of p. 7 comes the passage that really engaged my whole imagination. On p. 8 the bit beginning o whip ship is good. Suburb-house on p. 9 I think bad. It is not real prose English (wh. would be suburban house) nor is it ‘poetical’ in the other style: i.e. it makes the worst of both worlds. p. 11, this island fact–at length is v. nice. The fluting ray on p. 11 is excellent–a truly poetic, and not merely fashionable, use of the Sitwellian technique.

I think the Love lies bleeding poem is good, but can’t be sure till I’ve read it several times: but I’m sure about the yellow drops of tree’s wine etc on p. 15: that’s fine–and almost the whole of p. 16.

On p. 19, try to excuse me for saying ‘Souls–Ideas–Universals’ is thoroughly bad. I fear you were among the Clevers when you wrote that. Don’t you see that you are merely asking us to write your poem for you–giving us the conceptual skeleton instead of presenting the concrete imaginative and emotional experience. Of course on that skeleton I can reconstruct the experience: but when I buy a poem I expect to have something more done for me than I could do alone whenever I chose. I want to be forced.

Bottom of p. 20 is nice: bottom of 21 (Until--reach) I happen to know the experience so well that I can hardly judge whether you have brought it off. 148 P. 22 last line but one e’en. Do you like this? The Oratory v. good, I think, specially the part on p. 26: and the part about brass in cots and brass in Hyperion is interesting and new. First paragraph of The Book is excellent, except for the line of beauty: but more of that anon. P 32 Repeat children still will be three times aloud before an imagined audience and see how you like it! Not only the sound but the false archaism of still for always and the whole apologetic air. P 35 For sleep…God’s memorably said. The whole of the Apple Tree poem is good. The Capture, good: but is it good enough? The Prospect: I wonder would you agree that At mystery and all that follows it is a failure. I wish you would banish words like Mystery & Beauty. The Lure tho’ a good piece is crippled by ‘Beauty’.

Surely Beauty is an abstract universal, a comparatively new inhabitant of the mind: it has no roots like such universals as Death or Love: it is a fatal non conductor to the imagination. As well–are you at all certain that what you are talking about is ‘beauty’?–surely that is not part of your experience but only a theory about your experience, and not a very profound or stimulating theory at that. It makes you write like Masefield (not that he can’t be good–but that is when he is writing about ships or foxes or something real–not about ‘Beauty’). P. 44 the second poem, very good. P. 45. dead Desdemon: the same penitential exercise as for children still will may be advised here! Prince of Darkness all good. Congratulations. P 50 dredged…desiring splendid: so also nearly all The Surrender: and the bird symbol on p 54.

Part II opens v. well: it may even be great, but I’d never say that of any poem till I had lived with it. p. 59 lovely and the para. She heard-without fire (p 61) bites like anything: then on to The Retreat. You are really getting going here: the whole thing from p 57 to 64 is most moving. What a falling off in New Heaven & Earth. The top of p 66 (versified literary history) is (forgive me) just dreadful: and all the similar bits henceforward. You are doing so very little more imaginatively, and so much less intellectually, than a good prose critic.

Part III begins magnificently. The Miltonic adaptation on p 74 (a bit of modern technique used really well) and ‘She walked…were one’ particularly went home. The Dream excites and moves me: but I’m easy prey to that sort of poetry so don’t take my word for it that it’s good! Bottom of p 87 and top of 88 a very good simile. Bottom of 88: something very prosaic in the midst of poetry often works, but not always. 149 The moderns are getting into the habit of thinking they can use this device instead of poetry. I think you have fallen into this trap. ‘Nothing seems to matter’ will pass in conversation: but I know nothing more from it in your poem than I should know from it in conversation: it has none of the divine precision of poetry. In the Middle of the Night, first stanza, good. Now on p. 98 This door’s shut fast. It cannot be undone is a good example of the prosaic rightly used, and very moving (Because, this time, it is not the substitution of conversation for poetry but merely conversational syntax applied to something really imagined) The dream of Andrew Marvell doesn’t, to me, come to life at all until the middle of p. 121. Perhaps I am missing the whole point. Oh–I’d nearly forgotten The Retreat, which I liked.