When I started shooting, I didn’t give much thought to the ammunition, or ammo, I used. I picked ammunition based on price and chose a slightly higher-priced brand, assuming that would get me decent-quality ammo. While price is a factor with ammunition, understanding how ammunition works and the variables that affect performance and reliability can help you make an informed decision.

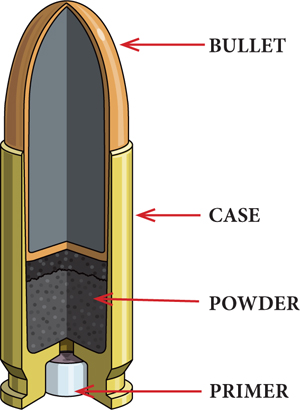

There are four basic components to a cartridge:

Bullet

Many people colloquially use “bullet” when they often mean cartridge, ammo, or round—all terms that denote a fully loaded cartridge. A bullet is the projectile that is loaded into a cartridge. A bullet by itself is just an inert hunk of metal. You can’t “load a gun with bullets”; this would literally mean putting bullets somewhere into the gun, but it wouldn’t be able to fire. A bullet must be combined with a case, powder, and primer to form a loaded cartridge, also called a round.

Bullets next to fully assembled cartridges.

There are many different shapes and forms of construction. “Ball” ammo is a standard type of bullet for target practice and other uses. Ball ammo is often a “full metal jacket” (FMJ), which means that the bullet is made of a lead core, and completely covered in a metal coating. This coating helps increase velocity, improve accuracy, and reduce the amount of metal deposits left in the barrel after each shot. Other types of bullets, such as hollow points, are meant to expand upon impact and have different designs and are made of different metals. This is only a small sampling of the many bullet shapes and materials available.

Case, Shell, or Cartridge

Most cases are made of brass, and you’ll often hear shooters refer to cases as “brass.” The case has an empty space for the powder and the primer. The case is marked with the specific caliber on the headstamp.

Headstamp on a .45ACP case.

Powder

Powder is the primary propellant in a cartridge.

Primer

I like to think of a primer as a snap cap. The hammer, striker, or firing pin of a pistol hits the primer, which creates a small spark. This in turn ignites the primary powder charge in the case, which in turn creates enough pressure to force the bullet out of the case.

Rimfire vs. Centerfire Ammo

There are two basic types of ammunition: rimfire and centerfire. A rimfire cartridge is one where the rim of the cartridge needs to be struck by the weapon’s firing pin. That force ignites a percussion cap, which in turn ignites the powder behind the bullet.

A centerfire cartridge is simply one where the center of the cartridge (instead of the rim) has the primer, which when struck, ignites the powder charge.

Some basic differences between the two:

Rimfire:

Centerfire:

Rimfire ammo is generally cheaper than centerfire ammo, but it really depends on the quality of the bullet, powder, and the brand’s reputation.

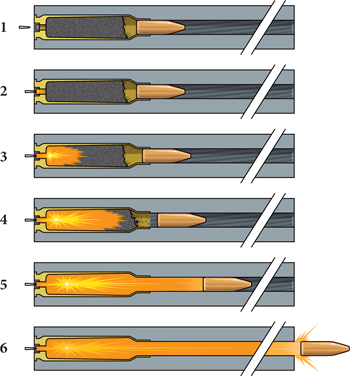

Pistol and rifle rounds have the same fire sequence: 1) Trigger pull releases firing pin, which strikes the primer; 2) primer explodes, creates a spark, and ignites the powder; 3) As powder burns, hot gas builds up pressure; 4) Hot gases force the bullet out of the case; 5) Hot gases propel the bullet through the barrel; 6) Bullet and hot gases exit the muzzle.

Caliber

Caliber is the diameter of a bullet at its widest point. Caliber is measured in both inches and millimeters. Sometimes the stated caliber includes the unit of measurement, such as “9mm,” which would be spoken as simply “nine millimeter.” Some caliber designations do not include the unit of measurement, such as “.40 caliber.” The latter designations often include additional descriptors that signify a different case, or bullet length or shape, such as “.22LR,” “.380ACP,” “.38 Special.” “ACP” stands for “Automatic Colt Pistol,” which is different from .45 Long Colt and other types of .45 caliber cartridges.

There are too many calibers to list, but for the beginner I would advise focusing on the following (in ascending order of size): .22LR, .380ACP, .38 Special, 9mm, .40, and .45ACP. I recommend these calibers because they are widely available. You will want to research the cost of each to make sure you can afford to practice. The ammo will get more expensive as you go up in caliber, but certain types of match-grade and self-defense ammo can be more expensive because of special features and higher-quality components.

For your first gun, I recommend avoiding caliber designations with “magnum” in them, such as .357 and .44 magnum because such large-bore cartridges cause strong recoil in a firearm. Save that for your second, third, fourth guns and beyond, or find a friend or range to loan you one so you can try it out. Dirty Harry’s Smith & Wesson Model 29 .44 Magnum is one pistol you have to shoot at some point in your life. Magnum rounds have increased powder loads, and while they are a ton of fun to shoot, they are not good to learn on because of the significant recoil. Unmanageable recoil can inhibit a beginner’s development because learning the fundamentals of sight alignment and trigger control is that much harder.

Fun tip: If you ever want to start a vibrant discussion, ask a seasoned shooter what his or her preferred caliber is and why.

I highly recommend that beginner shooters buy factory-loaded ammo. As you progress in your training and interact with other shooters, you may discover reloaded ammunition that can be trusted.

One thing that almost all shooters recommend is saving your brass after firing a round.

On the left, a bullet in its case; on the right, the empty, fired brass.

This brass can be reused, which can save someone a lot of money. Even if you never plan on reloading your ammo yourself, you can sell your used brass to someone who wants to reload. It’s basically free money lying on the ground at the range. One way of thinking about this is, why would you leave a bunch of nickels, dimes, and quarters just lying around?

A note on proper range etiquette: you should only collect your own brass in case other shooters want to keep their own. You’re welcome to ask a fellow shooter if they plan to keep their brass. If they say no, you’re welcome to grab it. Some ranges do not allow shooters to collect their own brass, which means the range is making money off of your empties. If you want to save your brass, the only option is to find a range or location that will allow you to collect your brass.

Chapter Summary: