State, Market, and Postsocialist Film Industry under Neoliberal Globalization

Introduction

Since the late 1970s, mainland China has undergone a sea change with a decisive turn from socialist governance and centralization to postsocialist marketization and privatization. Market as a new cultural logic and a dynamic integration of transnational capital fostered around the neoliberal axis become the major forces reshaping a wide range of economic, political, and cultural lives in postsocialist China. With China increasingly predicated upon the flourishing market rationality and its restructured relationships to the global capitalist system, a theory of neoliberalism thus becomes a resourceful tool and instrumental method to understand the significant political and social changes of postsocialist China and the pivotal transformations in the film circle as well.

Many scholarly studies on neoliberalism in China tend to invoke this neoliberal model to describe a new condition of market-driven productivity and a new tide of consumption revolution in postsocialist China.1 But an important point is also made that, unlike the West, the neoliberal market reform in China has been substantially and always associated with the state imperatives in the sense that from its inception to implementation to expansion the Chinese state plays a dominant and authoritative role. It can be argued that to a great extent, Chinese neoliberalism represents a state ideology or a technology of “governmentality” in Foucauldian terms that justifies and identifies with the market power and the very social transition in postsocialist China.2 For anthropologist Lisa Rofel, it moreover signifies a psychological and social condition, within which new forms of desires and anxieties, subjectivities and humanities are intricately produced and circulated.3 In Desiring China, an essential and focused deliberation on neoliberalism in contemporary China, Rofel examines the issues of gender politics, public culture, and everyday life in the context of neoliberal reform. The ethnographic mapping of Chinese reconfigurations in relation to neoliberalism, albeit in a comprehensive endeavor, tends to leave the poetics and aesthetics of neoliberalism in cinema and other forms of audiovisual arts insufficiently touched, with the exception of her final and cursory glance at two films—The Postman (Youchai, directed by He Yi, 1995) and Living Elsewhere (Shenghuo zai biechu, directed by Wang Jianwei, 1999). As she points out, these two particular films, in a hyperrealistic fashion, present a critical view of the neoliberal postsocialist practice and its pathological effects on urban subjects and migrant workers. Both were primarily circulated around underground venues and have limited distributions in China, as opposed to the success they garnered on the international film circuits.

Departing from this originative line by Rofel, yet in a deliberate attempt to interrogate this traditional assumption of the binaries between artistic/commercial, alternative/mainstream film, public culture and everyday life/official narrative, this chapter will take an inverse position to launch a sociohistorical reading and close analysis of “Leitmotif” (zhuxuanlv) film, a heavily state-sponsored film genre shaped by both the market and state mechanisms in the postsocialist reform. Very little has been done historicizing and theorizing this market-sensitive film genre in the neoliberal postsocialist context, a significant theme marginalized by the festival-oriented scholarship of Chinese film studies in the last past decades.

Leitmotif, a characteristic Chinese film formation with an explicit musical reference by its name, is a newly formulated state-subsidized film project that has experienced unprecedented growth and popularity at the turn of the new century. A privileged and highly figurative term that is often linked with state sponsorship and political intervention, the category of Leitmotif poses complex questions for cultural critics, film historians, and theorists of mass media. Generally seen as conforming and didactic, one may ask: what is the value in studying such blatantly propagandist films? How does a critical study of this genre enable us to rediscover the continuing significance of ideology criticism to cinescape, reevaluate the positioning of propaganda in cinema in the current milieu as it is intertwined in a convoluted way with the mechanisms of nation-state, neoliberalism, and global market? Moreover, whereas China has officially adopted an open-door policy, market reform, and a series of structural adjustments, the state is still reluctant to let loose its ideological and political controls. As a cultural product of these nuanced, often contradictory principles and rationales, how does Leitmotif reflect and bear witness to this economically liberal but politically conservative climate with “Chinese characteristics” in the late socialist era?

As Chinese film signifies one of the first ventures to incorporate a capitalist business model and represents China’s fin de siècle aspiration and anxiety to “link up with the tracks of the world” (yu shijie jiegui),4 the cinematic display encoded by nationhood, historical reflexivity, and transnational imaginary has also become one of the defining features of Leitmotif films, such as in Bethune: The Making of A Hero (Baiqiu’en: yige yingxiong de chengzhang, directed by Phillip Borsos and Wang Xingang, 1990); Red Cherry (Hong Yingtao, directed by Ye Daying, 1996); Red River Valley (Honghegu, directed by Feng Xiaoning, 1997); Opium War (Yapian zhanzheng, directed by Xie Jin, 1997); My 1919 (Wode 1919, directed by Huang Jianzhong, 1999); Grief over the Yellow River (Huanghe juelian, directed by Feng Xiaoning, 1999); Shadow Magic (Xiyangjing, directed by Hu An, 2000); Purple Sunset (Ziri, directed by Feng Xiaoning,2001); and Charging out Amazon (Chongchu yamaxun, directed by Song Yaming, 2002). These Leitmotif films are often considered as the Chinese blockbusters in that genre abundantly borrows and deliberately appropriates the images and neoliberal practices from Hollywood hits. Through a case study of the box-office winner in 1999, Grief over the Yellow River by Feng Xiaoning, this chapter attempts to address the following concerns: How do the key concepts of neoliberalism, such as free trade, global market, and universal humanity, find thematic resonance in Leitmotif films and help anchor cultural belongings and national consciousness on new grounds? In what ways does this institutional and textual emulation manage to refashion and resell a sense of nation-state in the market age, as the party-state is confronted with a severe challenge of social unrest, political disillusionment, and credibility crisis? Particularly, what role does the narrative paradigm that prevalently features the East-meets-West play in the formation and marketing of this new film genre particularly, a form of cultural imaginary in general? This cinematic encounter and configuration, I argue, represent a specific, often sophisticated way of reconstructing China as a neoliberal entity technically, textually, and aesthetically. It has become a plural and fraught site in which a more complex and ambivalent picture of the neoliberal world order and China’s self-reflexive image are projected on the screen and heard over the soundtrack simultaneously.

“Leitmotif and Diversity”: State, Market, and Chinese Film Industry Reform During the Postsocialist Period

A coinage growing out of the Western Romantic tradition, Leitmotif as a specific music idiom can be traced back to Richard Wagner’s idea of “motifs of reminiscence,” which is by definition a central, characteristic, and recurring musical theme that has a strong connection to a particular character, time, setting, and scene. The classical Romantic convention that emphasizes leitmotivic structure, theme writing, and symphonic orchestrations had a dominant impact in classical film score.5 In the Chinese circumstances, Leitmotif is a borrowed term figuratively referring to a national film practice characteristic in postsocialist China, with the goal of satisfying both the political interest of “depicting the major trends of the reforms and the historical era” and the economic demand for “market” and “diversity.”6 In other words, it is a metaphoric adoption that intends to resurrect and anchor the continuing significance of state ideology in the neoliberal cinematic context.

An essential component of the slogan “Foregrounding Leitmotif, Persisting in Diversity” (tuchu zhuxuanlv, jianchi duoyanghua), the concept of Leitmotif was initially brought up at a meeting of the principals of national film studios in March 1987 to guide a full scope of artistic practices in the postrevolutionary period. Originating in the heyday of the market reform, “Leitmotif” has been often paired with “Diversity,” symptomatic of the conflation of the socialist conventions and neoliberal spirits of “market fever” and “culture fever” (wenhuare)7 in the late 1980s. A pragmatic response to the profound change under the new market condition, this narrative also appears to encapsulate a range of ruptures, tensions, and contradictions within the reform itself. In particular, it was formulated to correspond to the alert of a campaign against “bourgeois liberalism” (zichan jieji ziyouhua) in early 1987. Writing an article that was collected by China Film Yearbook 1990, Liu Cheng, who later produced a Leitmotif film, Kong Fansen (1995), indicates that “bourgeois liberalization” is one of the most harmful tendencies in the films of the late 1980s, as “we found more representations of hooligans, enemies, spies, and prostitutes on the screen … but less class analysis of characters and … fewer positive depictions of workers and peasants.”8 Liu argues that in order to purify the film market and save films from the “spiritual pollutions of bourgeois liberalization” (zichanjieji ziyouhua de jingshen wuran), the political directions of cinema need to be redressed and its pedagogical function reinforced. Many other articles on the future direction of Chinese cinema shared a similar point of view.

Under such circumstances, it becomes natural that a notion of Leitmotif was propagated from the top down as a regulative device subsequently applied to the film sector. Overseen by the state, many films were tailored to the depiction of the positive Party image, great achievements of the reforms, and the glorious events and leaderships in history:

At first stage, we are interested in using the definition of “Leitmotif’ as a classifier of genre, to explore and promote the realistic themes of agriculture and industry reforms and images of new leaders. But after practice, we found that it is far than enough to underwrite the significance of ‘Leitmotif’ in terms of genres and subject matters. It should be elevated to the spiritual level, namely, an overriding spirit and voluntary consciousness in the artistic practice to embody and advocate the reformist, socialist and patriotic ethos of the time.9

As indicated above, film officials have shown their strong support for Leitmotif not only by establishing its leading roles among film genres, but furthermore through the sanctifying process, in which it has been iconized as “a spirit of creation” overdetermining the form and content of mainstream filmmaking in the new era. The category of Leitmotif thus can be extended to include “any films that have positive and healthy content and are exquisite in quality.”

Whereas the notion of “Leitmotif” has been officially sanctioned since the late 1980s, it didn’t thrive on the Chinese screen and evolve into a fullblown genre until the next decade. It was not until the 1990s that Leitmotif films experienced enormous popularity and unprecedented growth. The anniversaries related to the key events of the Chinese revolution from 1991 (the seventieth birthday of the Chinese Communist Party), to 1995 (the fiftieth anniversary of the victory of Sino-Japanese War), to 1999 (the fiftieth anniversary of the PRC’s founding) were frequently cited as the direct causes that contributed to the flourishing of this genre. Besides these, another pivotal link should also be taken into account, namely, the structural change and marketization of the Chinese film industry. Deeply embedded in a neoliberal scenario, the Chinese film industry reform, I argue, significantly parallels the trajectory of Leitmotif film.

With “a series of ‘deepened’ (shenhua) reforms, or more thorough marketization,” the Chinese “socialist film system began its tortuous metamorphosis into a (quasi-capitalist or state-capitalist) industry.”10 A bold and thorough effort to substitute the neoliberal capitalist mode for the state-planned economy took place, first in the distribution-exhibition sector. By specifying the distribution being taken care of by the studios themselves and market as the primary source to determine ticket price, instead of having China Film Corporation set prices as previously, the 1993 –1994 reform was a decisive take to emancipate studios from the CFC’s distribution monopoly. Moreover, as the reform pushed the film institutions towards a greater extent of economic independence, government involvement in the form of financial support was greatly reduced. As a result, capital investments from private avenues both domestic and foreign were involved, which opened the floodgates to a new wave of “coproduction.” Film companies were established with private funding, and independent film producers who are remotely or no longer under state control appeared. In a transition to a capitalist business mode, the neoliberal entrepreneurial spirit was ushered in to take postsocialist Chinese film onto a different track.

Whereas the overall institutional reform was steering towards greater autonomy and diversity, the state, with an economically liberal but politically conservative stance, was still reluctant to completely unleash the film system into the market. By the mid-1990s, the increasing political pressure and conservative cultural environment resulted in the implementation of a set of restrictive policies on literature and arts, such as the “Five Ones Project” (wuge yi gongcheng)11 launched by the Central Committee’s Ministry of Propaganda and “9550 Project”12 imposed on filmmakers specifically. Primarily aimed at reasserting the pedagogical and ethical functionality and regaining top-down control of film and media production, the institutional reform of 1995–1996 was an important move to overtly privilege Leitmotif films, thereby propelling its immense popularization in the midto-late 1990s.

Starting from the early 1990s, filmmakers began to undergo a tortuous divorce battle with the state, and gradually assumed the entrepreneur role, more closely responding to market forces rather than the government mandates. This change can be seen in the Fifth Generation filmmakers who, after building their fame in the 1980s with a heavy reliance on state financing, began to place priority on audience and the market. These semi-independent films, now primarily financed by private investment and Western capital, had to nevertheless punctiliously seek a balance between market and state. Chen Kaige’s Temptress Moon (Fengyue, 1996) and The Emperor and the Assassin (Ciqin, 1999), and Zhang Yimou’s The Road Home (Wo de fuqin muqin, 1999) and No One Less (Yige dou buneng shao, 1999) are good examples of the shift of the Fifth Generation, who, in the post-1989 period, turned to the market liberal yet politically cooperative tactics, and sometimes even overlapped with the official rhetoric of Leitmotif films.

Another equally important scenario is the Sixth Generation, whose films were made outside the official production system and nearly inaccessible to the general audience in the mainland. The succession of a film being banned, attracting the attention of a “liberal” Western world, and returning home with international accolades (hence the lift of the official ban) may illustrate an alternative mode of market rationality in the non-Western contexts, or a form of “neoliberalism as exception,” to borrow Aihwa Ong’s formulation.13As Ong forcefully argues, neoliberal interventions in postcolonial, postsocialist situations articulate a different relationship between market mechanism and state sovereignty from the Western liberal democracies. To put it in another way, neoliberalism that promotes individualism and entrepreneurialism is repositioned, reterritorialized, and reconfigured in the sites of transformation where neoliberalism itself is not the general feature of “governmentality.” Meanwhile, when the self-governing and self-enterprising values are translated into a particular milieu, these new arrangements and reterritorializations of capital, labor, and knowledge are quickly merged into the global market to form a new cycle of neoliberal movement. This neoliberal exception logic well explains the preceding phenomenon and the increasingly varied, contingent, and ambiguous space within which Chinese cinema resides. Since the end of the Cultural Revolution, when a neoliberal ethos took root in a large scale of socioeconomic and cultural domains, many independent artists have surfaced from the underground to join the mainstream market. In a very interesting way, making a nationally controversial yet internationally recognizable film has become a shortcut to entry into the mainstream. A bunch of films with a staple of “edge” or “margin” targeting at international film festivals and small audiences in art-house cinema are products of this exceptional logic of neoliberalism.

By contrast, a notion of “New Mainstream Cinema” (xin zhuliu dianying) was formulated concurrently among a group of young filmmakers in Shanghai. Keen on the market power and fast-changing environment neoliberalism has engendered, they began to advance a new form of cinematic practice that embraces self-enterprise and market-driven modes of governing. In “New Mainstream Cinema: A Suggestion on Domestic Filmmaking,” the first work to undertake a comprehensive exposition of “New Mainstream Cinema” theory, Ma Ning begins with the premise that unlike the Sixth Generation’s alternative film that placed much emphasis on the stylistic and aesthetic experiment, “New Mainstream Cinema,” being a mediator between the marginal and mainstream, is intended to form and develop “the innovative low-budget commercial film.” Future directions are suggested in this manifesto: (a) as a discursive strategy to save the national film industry from the crisis, accelerated and exacerbated by globalization and Hollywood’s market penetration, independent filmmakers are encouraged to move out from the peripheries towards the center and possibly align with the official apparatus; (b) it requests state sponsorship with the budget of 1.5 million to 3 million yuan (approximately 0.2 to 4 million U.S. dollars), whereas filmmakers as individuals should take other matters into their hands with greater autonomy and less restrictions; (c) this model, neither preoccupied by the political and ideological orientations nor indulged with an avant-garde and polemical edge, is instead committed to the commercial appeals, clinging closely to the concerns of mass audiences. Interestingly, “New Mainstream Cinema,” formulated under the rubrics of neoliberalism, is an explicit call for the middle ground where film-as-business and filmmaker-as-entrepreneur will be securely anchored and mutually defined by market and state. It is also a rewriting of “Leitmotif and Diversity” in the face of the challenge from the shrinking national film industry and the invasion of Hollywood globalization at the turn of the new century.14 However, some of the problems emerging from this model cannot be ignored. It is hard to know, first of all, whether or not the proposition that attempts to win over both the official acknowledgment and market profit is feasible in the long run. As a matter of fact, the plan was aborted soon after and most of the films in the blueprint were never completed. Secondly, it was unclear and little was explained about how this solution operates in relation to and in negotiation with the two opposites—Leitmotif and alternative films.

Hollywood Neoliberalism, Chinese Blockbuster, and the Global/Local Dialectics

Given its vast output, Leitmotif film has occupied a preeminent place in the contemporary Chinese culture industry. According to Li Yiming’s estimation, in the mid-1990s, Leitmotif films reached 20 percent of the annual output, whereas other kinds of entertainment films totaled 75 percent and art films 5 percent.15 The proportions of Leitmotif continued to grow in the second half of the 1990s and reached their peak at the dawn of the new century, when the PRC was to celebrate its fiftieth anniversary. Not only were these films labeled “A Tribute to the Nation,” but they were also seen as a milestone signifying the resurgence of mainstream, political film in the postrevolutionary period. The direct or indirect intervention from the state agencies cannot be underestimated. Leitmotif film as a propaganda machine is highly monopolized by the state almost in every aspect of its operation. Not only is it produced, packaged, advertised, and promoted by the official apparatus, but also a great deal of box office is ensured by work units and social groups who are collectively organized to fill up the theater seats.

As one of the earliest Western scholars who writes about Chinese film, Chris Berry was highly critical of the contrived and dictated popularization of Leitmotif, pointing out that its massive productive and relatively high box-office return shall no elude some of their “conservative” objectives: “denying difference and blocking changes.”16 “This return to revolutionary history is an attempt to reunite precisely those fragments … The People’s Republic is shattered into by the shock of Tiananmen.”17 Whereas it is true that this new paradigm exhibits a certain setback from the diversified, liberal discourses of the 1980s, the rise of Leitmotif nonetheless suggests a fundamental turn in the new age. The development is evidently perceivable, as it incorporates the market force and neoliberal sensibility into the new formula on both economic and aesthetic terms.

The “changes” or “progress” are twofold. First, as Chinese society has become more diverse and interactive with other parts of the world, another hue has been added to the vast canvas of rewriting national history, namely, a growing fashion in the Chinese film industry to make films with the subject matter of East–West cultural clash and reconciliation. In other words, it is a trend within the genre of Leitmotif to offer an alternative view on modern Chinese history by foregrounding the dynamics between nationbuilding and transnational-imagery construction in ways not previously explored. Second, although the ideological-propagandist function of such films continues to be prioritized over their entertainment value, studios’ concern for box-office return has pushed Leitmotif films towards adopting a market-driven formula, a formula that purports to emulate and is specifically inspired by the commercial success of Hollywood cinema.

The socioeconomic impact of Hollywood imports is another crucial aspect, in that a large corpus of Leitmotif films, is often, if not exclusively, discussed in comparison with its Hollywood counterparts, labeled as “Chinese blockbusters” or “big pictures” (dapian) as such. This coinage, by implication, has suggested a business pattern that is attributive or similar to Hollywood as much as its divergence is attuned to the local sensibilities. Two factors are reported to contribute to this singular synthesis: the recession of the Chinese domestic film industry and the simultaneous erosion of Hollywood blockbusters. Starting from the mid-1980s, the Chinese domestic film market continued to decline, whereas Hollywood began its reentry into China under a revenue-sharing arrangement from 1994. The annual output of the domestic films of 1995 was around one hundred films per year, which received only 30 percent of the box-office revenues, whereas the other 70 percent went to ten big imports (six from Hollywood). The shadow of Hollywood loomed larger over the Chinese film industry in 1997 and 1998. Titanic and Saving Private Ryan accounted for about onethird of the total box office in Beijing and Shanghai. To prevent a further collapse of the domestic market, Ministry of Film Radio and Television and the Ministry of Culture issued a joint circular in the spring of 1997 to mandate the allocation of two-thirds of screen time to the domestic films, especially “quality films,” namely, the quintessential national films in the mold of Leitmotif. China Theater Chain, was accordingly built to guarantee quality domestic films with the best and most screen time. More importantly, a series of ad hoc measures were taken to relieve the tax for these film exhibitions and to increase the average budget of a domestic feature from 1.3 million yuan (approximately U.S.$0.15 million) in 1991 to 3.5 million (approximately U.S.$0.4 million) in 1997.18

The widespread, crushing impacts that Hollywood neoliberal products had on the Chinese film industry is a double-edged sword: it led to a cinematic space loaded with tensions and anxieties, yet simultaneously provoked a rise of Chinese blockbusters, activated and made possible by the very new openings to Hollywood and global capitalism. “The idea of the ‘blockbuster’ has been appropriated into local critical discourse, to refer not only to American blockbusters but also to local productions considered blockbusters,” writes Chris Berry in another essay, “‘What’s Big about the Big Film?’: ‘De-Westernizing’ the Blockbuster in Korea and China.”19 The Opium War (Yapian zhanzheng, directed by Xie Jin, 1997) represents Berry’s idea of a “localized blockbuster with Chinese characteristics” in its thematic concerns—the historical account of Hong Kong and free trade in a contemporary vein (which serves as a seasonable reflection of the handover of Hong Kong and China’s accession to the WTO at the turn of the new century); stylistic strategy—a historical epic; big budget—one hundred million yuan (approximately U.S.$13 million); big visual effects—spectacular on-location shooting with ten of thousands of casts and crews (it strikingly employed a transnational group, including three thousand foreign actors); along with the most advanced film equipment and technology of the time. This film signifies a conflation of two different subgenres, according to Berry, the “giant film” (jupian) and “big film” (dapian). Such a rhetorical distinction seems to be somewhat problematic, because a large number of “blockbusters” share with “giant films,” I would argue, similar generic characteristics such as narrative forms, social conventions, and the ascribed cinematic functions. Both draw on the resources of historical epics and serve political purposes. Moreover, it is hard to split them in terms of origins, for both of them could date back to the early 1990s in which “Revolutionary History Films with Significant Subjects” (zhongda geming lishi ticai de yingpian) flourished.

The year of 1991 witnessed a significant growth of Leitmotif films with depictions of key leaders and historical landmarks of Chinese revolution, for instance, Decisive Engagement (Da juezhan, directed by Wei Lian); The Creation of a New World (Kaitian pidi, directed by Li Xiepu); Mao Zedong and His Son (Mao zedong he tade erzi, directed by Zhang Jinbiao); and Zhou Enlai (Zhou enlai, directed by Ding Yinnan). Primarily dealing with party leaders, historical events, and critical moments of socialist triumph over foreign, capitalist controls, these films were promoted as a special version of blockbuster that foregrounds Chinese nationalism and collective consciousness via various forms of government support. First, an abundant supply of finance, labor, and production equipment was generously provided by the government. Secondly, in the distribution-exhibition sector, the government promoted these films by requiring the affiliated institutions, work units, and schools to purchase tickets for their members as either a form of “political study” or “social welfare.” The third method to cultivate Chinese blockbusters was to elevate their artistic or aesthetic status by bestowing a series of film awards on them. Since the early 1990s, Leitmotif films have become the major recipients of numerous Chinese film awards such as the Golden Rooster Awards and Hundred Flowers Awards, the most prominent nationwide prizes set in the film category. The Huabiao Awards, an important government award supervised by MRFT and the Ministry of Culture, has showed an even stronger preference for Leitmotif films. Almost every year since 1990, the Best Picture has been invariably awarded to a Leitmotif film.

“Aimed at repackaging (or fetishizing) the founding myth of the Communist Party and socialist legacy in an age riddled with ideological and moral uncertainty,”20 Leitmotif films constitute a new and integrated paradigm to both address Hollywood neoliberalism and mediate the socialist discourse in an alternative and revisionist manner. Even though setbacks were found and doubts were expressed as to whether or not such a state-monopolized circuit of manufacturing, wholesaling, and distribution is feasible in the long run, Leitmotif films, forged under the blockbuster hallmark, have seen progresses that allowed studios to make profits and approach mass audiences in a more accessible way. A noteworthy development is that, in addition to the didactic imperative and market motivation, this film genre is molded after a higher artistic standard. According to one of the renowned Fifth Generation directors, Wu Ziniu, who started to make a retreat from his former marginal position into the mainstream arena in the 1990s, “Leitmotif films should not be misunderstood as shallow, vulgar works merely illustrating government policies.” Rather, talking about his experimental Leitmotif film—The National Anthem (Guoge, 1999), he intended this piece to be a kind of “New Mainstream Cinema” that would engage its audiences with an aesthetic improvement, a visual enjoyment, as well as a celebration of “patriotism and national spirit,” which have been achieved in some of the Hollywood productions—a form of “Western Leitmotif” in his view. Specifically, Wu cites Forrest Gump (1994) and Saving Private Ryan (1998) as the prototype of what he called “Western Leitmotif,” for both seek to promote “the American spirit” and “various American public opinions and ideologies.”21

In this light, it should come as no surprise that the optimal model that a lot of Chinese filmmakers and critics frequently refer to is in fact a mode of Hollywood neoliberal pictures where market rationalities, ideological needs, and artistic values are proficiently fused together. A close look at Feng Xiaoning’s Grief over the Yellow River (Huanghe juelian) in 1999 will help illustrate my point. Considered as one of the most important Leitmotif films and a representative of Chinese blockbusters, it was the number two box-office winner among domestic productions and was selected by the Chinese government to the Oscars for the competition of the Best Foreign Language Film in 1999. The film, however, failed and remained less well known in the international market. In the following section, I will compare this China-made war epic to Saving Private Ryan and Titanic, two of the most lucrative films in motionpicture history, on the aspects of visual representations, narrative structures, publicity strategies, and cultural impacts, and argue that Grief over the Yellow River is a Chinese neoliberal variation with rich intertextual references to its Hollywood counterparts.

(Trans)National Imaginary and Neoliberal Negotiation: a Case Study of Feng Xiaoning’S Vision of “China Through Foreign Eyes”

Constructed as an essential propagandist medium in the post-Mao era, Leitmotif has moved simultaneously towards market liberalism and the transnational circuit while maintaining its political edge. In What’s Happened to Ideology?, Lydia Liu, through her stimulating study of a popular televisual text of the 1990s, Beijing Sojourner in New York, asserts that the two different discourses of transnationalism and postsocialism are mutually embedded in the contemporary Chinese situation, thereby they must be treated as a simultaneous process. “Postsocialism by no means constitutes resistance to transnational capitalism, although it is a direct response to it; however, the existence of residual socialist thought, state apparati, and historical memory do complicate the ways in which transnationalism and its critique operate in a postsocialist context.”22 Just as transnationalism and postsocialism are no longer seen, in Liu’s proposition, as the binaries with the origin in a simple geographical West–East divide, neoliberalism should be understood as a plural, contested process wherein diverse spaces, histories, and national identities are projected and mediated.

This complex negotiation between postsocialism and transnational neoliberalism is best demonstrated in Feng Xiaoning’s trilogy of “China through Foreign Eyes” (Yangren Yanzhong de Zhongguo)—Red River Valley (Honghegu, 1997), Grief over the Yellow River (Huanghe juelian, 1999), and Purple Sunset (Ziri, 2001). Not only is it symptomatic of the resurgent Chinese nationalism in a postsocialist context, but also it has become a multiple and fraught site in which a more complex and ambivalent picture of the neoliberal world order and China’s self-reflexive image are projected on the screen and heard over the sound track simultaneously.

Following the sensational reception of Red River Valley, Grief over the Yellow River is the second sequel in Feng Xiaoning’s trilogy. It draws on the similar resources of what has been called “the revolutionary war pictures” and rewrites historical memory and East–West cultural clash through a well-designed “blockbuster” tool. The story is set in the closing days of World War II in the Chinese hinterland where an American pilot’s plane is hit by Japanese, but fortunately rescued by a Chinese shepherd boy and a unit of the Communist-led 8th Route Army. The central plot primarily revolves around how to save him and escort him to Yan’an, the Chinese revolutionary cradle as well as the symbolic home in the Chinese collective cultural imaginary. In the end, a team comprised of three Communist soldiers, including a beautiful Chinese army nurse, An Jie, who the American pilot Irving falls in love with, all sacrifice their lives in this mission. The film starts and concludes with Irving, who now becomes a grandfather returning to the Yellow River and the Great Wall to memorialize the Chinese heroes. This, to a great extent, resembles the thematic and stylistic strategies of Saving Private Ryan, where an elderly Ryan comes back to Normandy and stands before the captain’s grave marker to tell him that he has lived the best way he could. In the same manner, Grief over the Yellow River is a refurnished version to nostalgically recollect the war and make public history into private memory. Likewise, through the deliberate deployment of subjective flashbacks and voice-over narrations, a question of great significance that runs throughout Saving Private Ryan finds its peculiar resonance here: what is the value of human beings?

The film explores a number of possible answers, particularly through a detailed delineation of the marked convergence and divergence of the Eastern and Western ethics with regard to life value and the related notions of “sacrifice” and “surrender.” An intriguing sequence is exquisitely designed to present the East–West cultural clash by showing Irving’s involvement in a fierce quarrel with Heizi, the male Communist protagonist in the film. Upon Irving’s request of surrender to the enemies for the sake of stopping hurting other people in vain, Heizi responds, “We would like to die rather than surrender.” The deep focus on Heizi at the background and the crosscuttings between these two figures in juxtaposition with their verbal arguments on the sound track effectively display the discrepancy and cultural differences. In contrast to Chinese ideology, which champions and glorifies the collective interests and the honor of the nation, Western society and culture are distinctively represented as the ideal of liberty and freedom that gives most credit to the individuals. When the battle between these two factions almost reaches a deadlock, An Jie, acting as moderator, enters to cut off the fight and reinstate the balance through her elaborate explanation of the cultural gap.

This preceding text demonstrates how the Chinese state and its citizens in the 1990s, driven by neoliberal marketization, engage a historically momentous enthusiasm for self-reflexivity and draw their dynamic energies from global encounters. At the heart of these encounters and self-reflections lie complex negotiations of gender, class, national, and moral standards. If this particular scene addresses a neoliberal call to free human subjects from socialist “universality” and search for an “individual” and “private” humanity, the whole narrative then precisely echoes a postsocialist allegory of modernity in which people’s sexual, economic, and political self-interests are not only positively embraced and channeled on the national level but also reproduced across national borders to become cosmopolitan in a neoliberal globalized world.

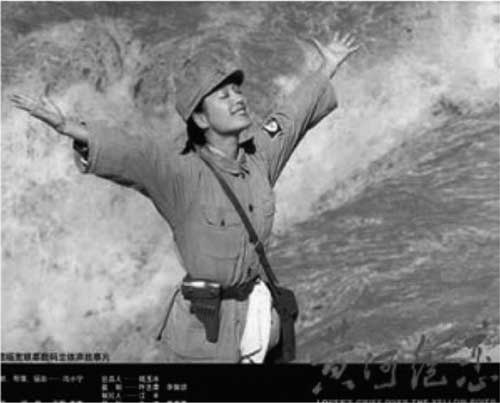

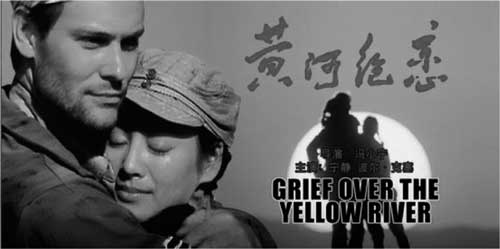

Apparently, Grief over the Yellow River is a cinematic text in response to the provocative debates and heated discussions after Saving Private Ryan was released in mainland China in 1998 (which set the top box-office record of the year, glossing around one hundred million yuan, approximately U.S.$13 million). Moreover, as a war epic loaded with heterosexual and transnational romance, it is an exemplary piece that borrows the ideas and practices of another big hit from Hollywood and efficiently transplants them to local circumstances. The particular image of the female protagonist framed by a full-circle panorama and positioned within the breathtaking mise-en-scène of the surging river, posing between flying over and embracing the water, is immediately recognizable as a deliberate reworking of the signature shot of Titanic (1997). Almost a commercial miracle in the mainland film market, Titanic set the box-office record with 359.5 million yuan (approximately U.S.$44 million). Aside from its integrated neoliberal market ethics, a number of external factors played in Titanic’s box-office triumph and smashing success. Upon his return from a visit to the United States, China’s President Jiang Zemin urged Chinese filmmakers to study and follow the example of Titanic. The film was interpreted as a good mix of romance and class conflict. In Jiang’s view, it provides a prime model of the integration of entertainment value and pedagogical goal in contemporary filmmaking. The Chinese highest official’s enthusiastic endorsement stimulated almost a full range of promotion of Titanic and consequently turned the film into an unprecedented national cultural event whose influence goes far beyond the movie theater.23

To ride on this sweeping wind, it is no surprise that Grief over the Yellow River bears a great deal of affinities to Titanic. An iconographic image of the female protagonist and the close-up of the melodramatic romance of a transnational couple in the posters and DVD covers’ designing are intended to boost its publicity and bring the film to the spotlight of Chinese cultural life. In addition, the Chinese title, meaning “a desperate love on the Yellow River,” would, on the one hand, readily remind viewers of its American counterpart—another version of the unfulfilled and tragic love story on the ocean; on the other, the underlying text of “Yellow River,” an embodiment of Chinese civilization, with its sharp contrast to the blue ocean, a unique symbol of Western culture in the Chinese imaginary, would furthermore assist its audiences to identify the film as a Chinese version of Titanic that accommodates at once the rhetorics of Hollywood global flow and the localized flavor.

Figure 8.1-8.4 DVD covers and film posters of Grif over the Yellow River.

In this regard, Grief over the Yellow River seems to be a visual comment on how Hollywood mega-productions penetrate the Chinese popular consciousness and reappear as hybrid coherent entities in the postsocialist context. Enjoying the widest release and earning phenomenal critical acclaims across the nation,24 this film together with Feng Xiaoning’s previous hit Red River Valley shall be considered as the “China-produced big pictures” or “Chinese blockbusters” that may fit into Chris Berry’s account. Not only do they belong to this designation by virtue of their “bigness”—big budgets,25 big stars,26 big effects,27 big publicity, big box-office return, but also they are in response to and dialogue with Hollywood films with similar themes. In an interview with one of the most widely circulated film journals, Popular Cinema, Feng Xiaoning explains:

At the end of 1995 when Chinese film industry suffered from a great depression, the major concerns of officials in Shanghai Film Studio was not only constrained by profit-seeking, but more importantly the experiments that purport to stimulate film market through big investments with prime artistic qualities has ushered in a new model of blockbuster of our own. All these factors have considerably contributed to the success of Red River Valley.28

As the first sellout in Feng’s trilogy, Red River Valley is a Leitmotif project recounting an important incident in modern history—the British-Tibetan war in 1904. The film is essentially composed of two parallel visual images and sound tracks. A Tibetan boy, Gaga, grows up and moves along with the trajectory of the whole incident. Conversations are barely heard in the first portion of the film, which portrays the Han–Tibetan relationship. Yet the crystal clear blues, whites, greens, and cheery reds that constitute the color theme and the jubilant laughter that punctuate the Tibetan boy’s nostalgic and reminiscent voice-over convey a sense of joy, intimacy, and human harmony. The second microstructure is a mimicry of the stylistic travel writing, with a third component—the Westerners—merging into and breaching the previous balanced relationship between the Han Chinese and Tibetans. In this part, it is the Englishman Jones who dominates the tale, both by his actions and his subjective points of view in a form of voice-over. Jones’s voice is distant and poignant as he somberly reads letters to his father, his principal confidant who is visibly absent yet audibly accessible through the sound track. The complex feelings of perplexity, dis/replacement, and dis/ reintegration as a consequence of his close exposures to the clash of two different cultures pervade this bittersweet transnational journey.

Figure 8.5 and 8.6 DVD cover and film poster of Titanic, directed by James Cameron, 1997.

Whereas this cinematic representation of nationalism and national identity relies on one particular genre—historical epic, the second strategy dwells on gender politics, particularly through the construction of transnational practices of sex and desire that delicately embody the sensibilities and proprieties of neoliberalism and cosmopolitanism. Although interpreting the war as inevitably resulting from the encounter between two different civilizations, the film proposes and advocates the ideal of cultural harmony through mutual understanding and respect, and more provocatively, through transcultural affection and romance. This type of intercultural relationship and transnational practice is theorized in Pratt’s term as the “contact zone”—“the space in which peoples geographically and historically separated come into contact with each other and establish ongoing relations, usually involving conditions of coercion, radical inequality, and intractable conflict.”29 In a pioneering and critical diagnosis of travel writing, Pratt examines how a quintessential Eurocentric and orientalist scenario has constructively shaped and underlined this intercultural love paradigm:

It is easy to see transracial love plots as imaginings in which European supremacy is guaranteed by affective and social bonding; in which sex replaces slavery as the way others are seen to belong to the white man; in which romantic love rather than filial servitude or force guarantee the willful submission of the colonized.30

A similar pattern of cultural identification with and exploitation by the Western order can be found in a large body of Chinese Leitmotif films and Feng Xiaoning’s trilogy especially. In Grief over the Yellow River, this formulaic relationship takes place in the vast and landlocked yellow earth where an American is sent to China to “help” Chinese people during World War II and the airplane crash arranges such a rendezvous. An Jie, the Chinese Communist nurse, framed in fully lit shots, sometime prominently under high-key lighting, is portrayed as a glamorous and virtuous goddess in the mise-en-scène, and is repeatedly referred as an “angel” literally and figuratively throughout the film. She is the iconic mother-sister-lover who provides kindness, caring, companionship, erotic passion, or even selfsacrifice to the Western missionary. More strikingly, such a transnational engagement on the screen between the two protagonists, Ning Jing (who played An Jie) and Paul Kersey (the actor for the role of Irving), and their longtime collaborations have sparked an offscreen romance and interestingly paralleled their love relationship in the post– Cold War, neoliberaldominated reality.

All these textual and intertextual nuances seem to affirm a long-standing geopolitical hierarchy called “Western hegemony,” or, to borrow Pratt’s words, the constitution of an ingrained “concubinage system,” which is in fact “a romantic transformation of a particular form of colonial sexual exploitation.”31 It can be argued that a conflicting sentiment of love and hate and the ambivalent depiction of the Westerners at once as enemies and lovers have become universal themes in this specific genre. As such, a double vision with a certain extent of ambiguities has characterized the imagery of the West in Leitmotif films. Red River Valley presents two leading Western figures. The portrait of Rockman, the British Commissioner to Tibet, is sketched as cunning, treacherous, and devious, which primarily follows the clichéd narrative in most revolutionary epics; whereas his interpreter/correspondent Jones is contrastively depicted as more conscientious and humane. Several scenes and sequences juxtapose the vitality and openness of the West, along with its brutality and arrogance. Rockman, albeit directly accused as the major cause of the war, is presented with a more complex personality rather than as one-dimensionally villainous. In the climactic scene, the crosscutting alternates the close-ups between Rockman’s gaze and his Tibetan friend/rival. The lit lighter, a previous gift from him that incurs and ultimately ends the war, has been framed in the center a few times. A recurring motif of the film, the lighter is a metaphor of friendship and civilization as well as a destructive force. The end of the film is introduced by a melancholic piano score—the recurrent “main melody” of the film, interwoven with a montage of the flashbacks that recollect the idyllic past and the wounded memories of war. The final shot that shows Rockman’s regretful and tearful confession “you and I should have been friends” upon witnessing all the tragedies gives a humanist touch to his presumably negative character. In this light, the British intervention with the Tibetan/Chinese business seems to be mainly motivated by a neoliberal aim to compel the Tibetans/Chinese to open up free trade, a prominent theme that has its cinematic repercussion in another 1997 Leitmotif film, The Opium War.

Figure 8.7-8.8 The crosscuttings between Rockman and the Tibetan protagonist Geshang in Red River Valley.

Conclusion

Red River Valley, with its double imagery and double vocal track, reflects the double dynamic of Western reconfigurations and Chinese self-representations that permeates a large number of Leitmotif films. A corporate piece of government propaganda and Chinese blockbuster, the film was made and circulated in conjunction with a set of transnational capital, political sponsorship, and, most of all, the social-cultural life the neoliberal reform had produced. After the film was released in 1997, a considerable majority of review was directed to laud the film for its enthusiastic nationalism, revolutionary romanticism, and open-mindedness to the neoliberal transnational world. To follow this paradigm, Purple Sunset, the third piece in Feng’s trilogy, recasts the transcultural journey and encounter into another remote forest in northeast China. The film continues and extends Feng’s stylistic experimentation with flashbacks, voice-overs, and multilingual sound tracks. The central characters are a small group left stranded in the forest at the end of World War II: a Chinese male peasant, a Russian woman soldier, and a Japanese schoolgirl. They have to depend on each other to find their way out of the forest, despite their different nationalities, political interests, social identities, and languages. Like Feng’s previous works, a philosophical and at times platitudinous reflection on humanity and mutual understanding becomes the underlying message and leitmotif of the film.

Primarily funded by Shanghai Yongle Film Company, Red River Valley and Feng’s other epics all seem to support an emergent entrepreneurial spirit in negotiation with the governmentality of the state. The films’ commercial success is symptomatic of how the neoliberal principles of market and profitability in general, and the mass entertainment value of film in particular, have been woven into China’s postsocialist reality. When the market becomes the new hub and regulation force, a large number of profit-oriented film businesses appear and mushroom in the postsocialist landscape. Many of them, however, like Shanghai Yongle Film Company, Beijing Forbidden City Film Company, and Yima Film Company, are joint ventures of private management and local government ownership. At this point, we should remind ourselves that the neoliberal capitalist concepts of “free market” and “privatization” cannot be indiscriminately applied to China. Instead, Feng’s films and the similar works that are discursively grouped under the rubric of Leitmotif—a state-sponsored and market-driven transnational product—are best indicators of a new neoliberal formula in the postsocialist milieu. This convergence has been aptly phrased by historian Rebecca Karl as “a state-market-world linkage.”32 Comparing a 1997 Leitmotif film, The Opium War, with its revolutionary predecessor, Lin Zexu, made in 1959, Karl points out that although modern Chinese history seems to be nostalgically recalled in many recent Leitmotif films, this type of revisionist historiography and a reflection of the relationship between market and Chinese modernity bring new momentum to many contemporary cultural practices in the age of neoliberal globalization.

The double political and commercial stakes, nevertheless, play into the Leitmotif’s complicit position. Some doubts were raised to question its blockbuster rationality tinted with a propagandist tone, market hegemony that takes a neutral guise, and the representational strategies that identify with the orientalist ideology. The problem lies in the narrative structure and sound track as well. Red River Valley represents the complex relationship between Han, Tibet, and the West through the mediation of a Tibetan boy’s vision and voice in parallel with that of a British soldier. Both Mandarin and English are chosen to carry important dialogues, whereas the indigenous Tibetan primarily spoken in the assumed geographic area is nonetheless muted and barely heard in the film with the exception of a few musical and dancing scenes.

Whereas Leitmotif film has been widely circulated in the Chinese mainstream at the turn of the new century, the question of whether or not cinema can be both political, commercial, and artistic remains a debatable topic. Not only is Leitmotif, often interchangeable with “cinema of propaganda,” an unsettling and polemical construction, but also the “neoliberal” discourse that this film category is complexly associated with is constantly changing, remolded and even interrogated in the postsocialist environment, another contradictory and contingent process.

As the U.S. economy is now stranded within financial crisis and the global capitalist system is suffering from severe recession, Li Minqi and some other theorists assert that this current downturn and “demise of the neoliberal globalization” just in time anticipate and pave the way for a new upsurge of state-regulated capitalism. And China, who once again survives through this economic storm, serves as a good role model.33 Does this mean that a particular mode of postsocialist neoliberalism that has been normalized and internalized within the Chinese structure may in turn become an alternative and supplementary solution to free market capitalism? Or is this perhaps a prime time and great opportunity to be seized upon by the Chinese film industry, whose growth has been at once beneficially fostered and been dauntingly hindered by Hollywood’s neoliberal expansion?

As is seen, Leitmotif and the neoliberal-based philosophies, sensibilities, and interventions dominate the film circle and govern the social reality and everyday life in postsocialist China. Through this exemplary reading of Leitmotif, my chapter suggests that the historical, theoretical, and contextual understanding of neoliberalism and Chinese cinema is inseparable from the evolving landscape of postsocialist culture industry and should be always situated at the intersection of state-market-transnational. Zhang Yimou’s Hero (Yingxiong, 2002) and one of the most heavily invested pictures in Chinese history, The Founding of a Republic (Jianguo daye, made in 2009 to celebrate the sixtieth anniversary of the PRC), are two epitomes of Leitmotif in the recent era. With significant reliance on the state sponsorship on the one hand and transnational stars and capitals on the other, these Chinese blockbusters signal the maturity of what has been called a “state-market-world” synergy and may embody the neoliberal infiltrations from the East. How does and will this Chinese reconfiguration contribute to and rebuild the neoliberal sociopolitical order in general, and the world film market in particular? This remains to be seen and invites further exploration.

Notes

1 For the relevant discussions, see David Harvey, 2005; Minqi Li, 2004; Aihwa Ong, 2006; and Hui Wang, 2004.

2 Michel Foucault, 2000.

3 Lisa Rofel, 2007.

4 Zhen Zhang, 2001.

5 For further analysis, see Claudia Gorbman, 1987; Jeff Smith, 1998.

6 See Ting Xue, 1995.

7 The so-called “culture fever” is a heated discussion of the ideas, theories, and methodologies about modernity. It emerged in China in early 1985, blossomed into a nationwide socio-cultural movement in the following years, and was brought to a sudden end with the crackdown of Tiananmen Square in 1989.

8 Liu Cheng, 1990, p. 23.

9 Jianlong Zhai, 1991, p. 8.

10 Zhen Zhang, 2007, p. 11.

11 With an order that each province must create one “extraordinary” work in each of the five categories—film, television, literature, music, and theatrical performance—every year, the “Five Ones Project” of 1995 was built to place a number of new regulations on censorship, co-production, taxation, and the protection of the ratio of domestic films, along with the installation of certain official awards.

12 The reinforcement of a conservative film policy was advocated at a conference of Chinese filmmakers in March 1996 in Changsha. On the conference, a project named “9590” was launched to reinvigorate domestic film production by enhancing the quality of films. The goal was said to produce fifth “quality films” (jingpin) within the five years of the “Ninth Five-YearPlan,” an average of ten per year. When it came to the question of what was counted as “quality,” Ding Guangen, Minister of the Ministry of Propaganda, stressed in his talk, “Films should have the function of making audiences love the Party and their socialist country, rather than arousing their concern and dissatisfaction; film should advocate justice prevailing over evil rather than pessimistic sentiments, and should bring happiness and beauty to the audiences rather than wasting their time on absurdity and fabricated plots.” Four major parameters of “quality” films were listed and particularly supported by the Ministry of Radio-Film-Television: history, children, peasants, and the army, in contrast to some films that did not fit into Ding’s standard of “quality films,” such as Wang Shuo’s I Am Your Dad (Woshi ni baba, 1996) and Feng Xiaogang’s Living a Miserable Life (Guozhe langbei bukan de shenghuo, 1996). Both of them were ordered to be aborted during shooting or banned after production. See Jiazheng Sun, 1997, p. 8.

13 Aihwa Ong, 2006.

14 For discussions on “New Mainstream Cinema,” see Ning Ma, 1999, 2000; Jialing Song, 2006.

15 Yiming Li, 1998.

16 Chris Berry, 1994, p. 45.

17 Ibid., p. 49.

18 Ying Zhu, 2002.

19 Berry, 2003.

20 Zhen Zhang, 2007, p. 2.

21 Ziniu Wu, 1999.

22 Lydia H. Liu, 1998, p. 14.

23 Jian Hao, 1998.

24 Red River Valley was the second-highest grossing domestic film in 1997, garnering the Best Picture of Hundred Flowers Awards of the year; Grief Over the Yellow River, with the box-office of twenty million yuan and also the winner of a series of Golden Rooster Awards in 1999, was selected by the Chinese government to compete for the Foreign Film category for the 2000 Academy Awards.

25 Red River Valley was produced with a budget of twelve million yuan, Grief Over the Yellow River with a budget of 3.8 million yuan, compared to the average of 2.5 million yuan per feature in mainland China.

26 Both films starred Ning Jing and Paul Kersey.

27 These two films offer a series of breathtaking and magnificent sceneries of Yellow River, Yellow Earth, and Tibetan Plateau.

28 Mei Feng, 1997.

29 Mary Louise Pratt, 1992, p. 4.

30 Ibid., p. 97.

31 Ibid., p. 96.

32 Rebecca E. Karl, 2001.

33 For further discussion, see Minqi Li, 2008; Immanuel Wallerstein, 2008.

Bibliography

Barme, Geremie. In the Red: Essays on Contemporary Chinese Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

Berry, Chris. “A Nation T(w/o)o: Chinese Cinema(s) and Nationhood(s).,” In Colonialism Nationalism in Asian Cinema, edited by Wimal Dissanayake. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994, 42–64.

Berry, Chris. “‘What’s Big about the Big Film?’: ‘De-Westernizing’ the Blockbuster in Korea and China.” In Movie Blockbusters, edited by Julian Stringer. New York: Routledge, 2003, 219–229.

Cheng, Liu. “Dui 1989 nian guishipian chuangzuo de huigu” [A Review on the Feature Productions of 1989]. Zhongguo dianying nianjian [China Film Yearbook] (1990): 23.

Feng, Mei. “Ziji de dapian: caifang Feng Xiaoning” [Big Pictures of Our Own: An Interview with Feng Xiaoning]. Dazhong dianying [Popular Cinema] 6 (1997): 22–23.

Foucault, Michel. “Governmentality.,” In Power. Vol. 3 of Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984, edited by James D. Faubion, translated by Robert Hurley, and others. New York: New Press, 2000, 201–222.

Gorbman, Claudia. Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

Hao, Jian. “Taitannikehao zai zhong guo” [Titanic in China]. Dianying yishu [Film Art] 4 (1998): 19–24.

Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Karl, Rebecca E. “The Burdens of History: Lin Zexu (1959) and the Opium War (1997).” In Wither China: Intellectual Politics in Contemporary China, edited by Xudong Zhang. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001, 229–262.

Li, Minqi. “After Neoliberalism: Empire, Social Democracy, or Socialism.” Monthly Review 55, no. 8 (January 2004). http://monthlyreview.org/0104li.htm.

Li, Minqi. “An Age of Transition: The United States, China, Peak Oil, and the Demise of Neoliberalism.” Monthly Review (April 2008). http://monthlyreview.org/080401li.php.

Li, Yiming. “Cong diwudai dao diliudai” [From the Fifth Generation to the Sixth Generation]. Dianying yishu [Film Art] 1 (1998): 15–22.

Liu, Lydia H. What’s Happened to Ideology?: Transnationalism, Postsocialism, and the Study of Global Media Culture. Durham, NC: Asian/Pacific Studies Institute, Duke University, 1998.

Lu, Sheldon Hsiao-peng. China, Transnational Visuality, Global Postmodernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001.

Ma, Ning. “Xin zhuliu dianying: dui guochan dianying de yige jianyi” [New Main-stream Cinema: A Suggestion on Domestic Filmmaking]., Dangdai dianying [Contemporary Cinema] 4 (1999): 4–16.

Ma, Ning. “2000: xin zhuliu dianying zhenzheng de qidian” [2000: A Real Start for New Mainstream Cinema]. Dangdai dianying [Contemporary Cinema] 1(2000): 16–18.

Ong, Aihwa. Neoliberalism as Exception: Mutations in Citizenship and Sovereignty. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 2006.

Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Rofel, Lisa. Desiring China: Experiments in Neoliberalism, Sexuality and Public Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007.

Smith, Jeff. The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

Song, Jialing. “Zhu xuanlv dianying de weiji yu huolu” [Crisis and Solution for Leitmotif Films]. Dianying yishu [Film Art] 1 (2006): 53–55.

Sun, Jiazheng. “Duochu youxiu zuopin, fanrong dianying shiye” [Produce More Excellent Works, Let the Film Industry Thrive]. Zhongguo dianying nianjian 1997 [China Film Yearbook] (1997).

Wallerstein, Immanuel. “2008: The Demise of Neoliberal Globalization.” Commentary 226 (February 2008). http://www.binghamton.edu/fbc/226en.htm.

Wang, Hui. “The Year 1989 and the Historical Roots of Neoliberalism in China.” Positions 12, no. 1 (2004): 7–69.

Wu, Ziniu. “Pai Guoge de chuzhong” [My Original Intentions on Shooting The National Anthem]. Dangdai dianying [Contemporary Cinema] 5 (1999): 5–6.

Xiao, Zhiwei. “Nationalism in Chinese Popular Culture: A Case Study of the Opium War.” In Exploring Nationalisms of China: Themes and Conflicts, edited by C. X. George Wei and Xiaoyuan Liu, Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, 41–56.

Xue, Ting. “A Political Economy Analysis of Chinese Films (1979–1994).” Thesis, Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1995.

Zhai, Jianlong. “Guanyu zhuxuanlv he duoyanghua de dawen: dianyingju juzhang teng jinxian fangwenji” [Questions and Answers about Leitmotif and Diversity: An Interview with Teng Jinxian, the Director of the Film Bureau]. Dianying yishu [Film Art] 3 (1991): 4–8.

Zhang, Zhen. “Mediating Time: The ‘Rice Bowl of Youth’ in Fin de Siècle Urban China.” In Globalization, edited by Arjun Appadurai. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001, 131–154.

Zhang, Zhen. ed. The Urban Generation: Chinese Cinema and Society at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007.

Zhu, Ying. “Commercialization and Chinese Cinema’s Post-wave.,” Consumption, Markets and Culture Vol. 5, Issue 3 (2002): 187–209.