Neoliberal Attitudes and Architectures in Contemporary South Korean Cinema

South Korean Labor

Known to South Koreans and international audiences as a licentious filmmaker whose narratives pivot around sadistic, perverse, and slickly choreographed visceral violence, Park Chan-wook’s sensational impulses and aesthetic flair cleverly obfuscate his other concern in South Korean society: motifs of material and immaterial labor. Iconographic elements of the working class and “salarymen” litter Park’s mise-en-scène, from the proletariat figure, rugged and broken by extreme social circumstances, to the white-collar worker, laid off and similarly down on his luck. Their work environments, as crafted on screen, vary visually from cramped and bustling factory floors to corporate tower blocks, cosmopolitan high-rises, and lifeless office cubicles.

Equally, the tools themselves of the laborer and the corporate crony signify horrific modes of work in most of Park’s earlier films: iron pliers, carpenters’ hammers, box cutters, electrical tape, and jumper cables—objects that pertain to work done by hand—become weapons for defense or torture. Salarymen, overworked and loyal to their neoliberal provider, connote less strenuous physical modes of production as their attire and accoutrements remain unmistakably corporate—briefcases, dark-colored business suits, topcoats, and black umbrellas for Seoul’s damp climate. These animate and inanimate objects doggedly represent both the working and bourgeois classes as deprived of any socioeconomic power because of their alienation from one another and their power over its very production, something that Park also privileges in his fictional worlds.

Labor power becomes but one interest in this chapter but one I will revisit by way of Antonio Gramsci’s writings, little used in film studies. Moving to theorize his Pre-Prison Writings (1916–1926), and thus to depart from Marcia Landy’s highly applicable and innovative application of Gramsci’s other work,1 my use of Gramscian theory will be deployed to articulate what Park’s Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002) and Oldboy (2003) say about metalworkers and the bourgeoisie; and how different theorizations by Gramsci regarding social strata can translate into a visual vocabulary to analyze the narratological structure deployed in Park Chan-wook’s diegesis. I build on Landy’s text as well as Angela Dalle Vacche’s The Body in the Mirror (1992) and Angelo Restivo’s Cinema of Economic Miracles (2002); these seminal texts have helped me to understand Italian cinema and how Gramsci’s ideas remain relevant in the European context, but more importantly how a synthesis of his ideas can apply to East Asian cinema as well. It is from this work that theorizations of labor in relation to film have become clearer to me and that this materialist framework is worth pursuing. In essence, these two films remain committed to labor struggle by both the plebian and the conventional middle classes, whereby the marginalization and the radical impulse of these workers to resist is precipitously divided by class. Park’s Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance and Oldboy also happen to examine the apathy, vileness, and corporate dilettantism of an elite that tout neoliberal polices in South Korea of the 1990s and 2000s, as Gramsci did in a similar context in his critique of corporate fascism in Italy, albeit under a different period, that of monopoly capitalism.

Labor’s image is a difficult subject to bring to life filmically.2 But this is a subject that nonetheless refracts South Korea’s recent historical imaginary on screen, propounded explicitly by the workers’ struggles, which “greatly contributed to the democratic movement called the ‘Mingjung’ [that had shown] a clear continuity with the development of class struggle in the 1970s.”3 These social upheavals continued in the following decade with seven hundred strikes and 897 conflicts in the spring of 1980, stemming from many protests against the domination of authoritarian power that eventually came to an end in 1987.4 Following on from this political turn was the establishment of a supposedly democratically elected Roh Tae Woo regime from 1988 to 1993, and later South Korea’s entry into the WTO in January of 1995.5 However, Korea’s emergence onto the global economic stage brought with it new forms of socioeconomic suppression levied against the worker under a neoliberal imposition at the state and corporate levels.6 Several South Korean political economists see the turn to overaccumulation and a rise in the support of high-tech industries in the early 1990s as leading to the devaluation of the won, where, according to Dae-oup Chang:

Aside from making the character of Korean industry more capital-intensive, this allowed capitals to avoid involvement in the labor conflicts that started growing in 1987. In general investments in fixed capital during the 1990s, by contrast to capital investment during the boom of the mid-1980s, were focused on introducing new lines of products, the automation of the labor process and R&D, rather than quantitative expansion of equipment. Thus, whereas total investment in plant and equipment comprised 57.3% in 1987, in 1990 it fell to 31%.7

Chang’s thoughts point to the steady breakup of a skilled workforce by subverting their ability to be productive (trained vocational skills) as the induction of automation in factories led to layoffs. Thus, virtually any cooperation between workers and capitalists ended by the late 1990s, as the strident but tenuous connection that labor and the middle classes once shared with the privately run companies known as chaebols was eviscerated by the Tiger Market crash in 1997–1998.8 This economic downturn and its consequences for the working and middle classes seem to have triggered Park’s narratological impulse to punish forms of labor on screen, but for sociopolitical reasons. Identifying these problems as such has for Park on some occasions been called, in the words of film scholar Hyangjin Lee, a “crisis concerning the loss of cultural identity in the rise of South Korean cinema,” amongst other things, and is seldom associated with concerns over the rise of free market policies and practices in South Korea—a culture and cinema that accounts for the fiercest and most potent form of neoliberalism in East Asia.9

Because of the financial crisis, “both state and capital executed a series of unprecedented attacks against labor in the form of massive layoffs, legalization of unilateral dismissal by employers and the privatization of major public corporations such as Korea Heavy Industries, Korea Electric Power Corporation and Korea Telecom.”10 Many neoliberal variables such as mass unemployment and privatization are conjured in Park Chanwook’s Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (SFMV hereafter) and Oldboy. In these films, one can find reference to the recklessness of neoliberalization in real life, where structural adjustments created “austerity policies, liberalization of trade and capital markets, privatization of public companies,” which facilitated scant government regulation and cheap foreign capital that escalated the crisis for the worker.11 All of this came before the IMF stepped in during 1998, adjusting interest rates and pushing a tight fiscal policy for lending. These measures protracted labor even further, leading to “a three-year period from 1998 to 2000 where an astonishing 131,100 workers, or 18.3 per cent of all public workers had been laid off,” causing further indiscriminate class divisions and the rise of a neoliberal elite. As stark unemployment figures rose and the impervious nature of economic deprivation continued, neoliberalism permeated most Korean films made post-1998.12 It then seems important to read films like SFMV and Oldboy not only as horror films—although we need to acknowledge horrific moments—but to see them equally as films with an enduring fidelity to class.13 This specification by Park, to leave unresolved the boundaries of oppression through a grandiloquent narrative, speaks not to audience concerns, but to locate such tensions as they transmute into filmic fabrication. In other words, Park operates somewhere in a middle position—he is aware of more overt political films and events (Park Kwang-su’s A Single Spark, 1996, or Kim Ki-duk’s Address Unknown, 2001, to mass layoffs and casual workfare conditions), but he also, to borrow from Fredric Jameson’s writing on postmodernism, brings “an enrichment to the older conceptualizations of bourgeois society and capitalism (that is to say, its complex substitutions bring new contradictions usefully to the surface),” by playing with both Western and Korean aesthetic forms.14 But this compositional overlap, as I shall call it, of a Korean radicalism as it relates to labor and class politically, relies on the creative renderings that place his work also on film festival circuits. He accomplishes this by fictionalizing labor and its milieux through subterfuge, artifice, and stylized violence, made memorable in both films: an exhausting and diagonally shot corridor fight sequence where twenty-odd henchmen are impaled, slashed, and punctured by the claw end of a hammer in Oldboy; and a killing spree in another sequence in SFMV where a gangster’s skull is pulverized with an aluminum baseball bat, creating a ghastly grating sound as metal eventually finds pavement through bone. Despite the charged content found in these two sequences, Park insolubly weaves this violence together with labor exploitation. In essence, these two films utilize motifs of human carnage to historicize, even revalorize labor more believably and less didactically, through arresting narratives and lurid visuals that are undeniably linked to a continuously expendable caste of workers found in Seoul.

My central emphasis will be on demarking how power structures (institutions, social class, and city space) relate to Korea’s particular form of neoliberalism, the inimical effects of which are concretized through Park’s filmic representations in SFMV and Oldboy, the first two films of his vengeance trilogy series (Sympathy for Lady Vengeance, released in 2005, was the final installment). These two highly successful films can be seen to admonish a reconfigured and disastrous political economy that becomes a causality in Park’s South Korea through a crisis over class and space. Lush and well crafted, they appeal to the sensibilities and tastes of audiences worldwide because of their visceral and violent noir action, or, as Jin Suh Jirn has contended elsewhere, an “IMF noir.”15 Because gratuitous violence is now a staple in the global proliferation of film, little emphasis has been placed on Park’s films as responses to neoliberalism in what I see as embedded links with the characters’ attitudes (social stratification) and architectures (urban space) in the two films under investigation. As two startling metaphors that perpetuate such violence, what can be seen as a posturing of class and the built structure on-screen, these attitudes and architectures can be used to explore how the neoliberal project destabilizes communities in an age of “survivalist capitalism” during the unhinged 1990s and early 2000s.

Park as Anti-Neoliberal Filmmaker

Park Chan-wook’s rise to international stardom and popularity beyond the Pacific Rim is a wider testament to not only New Korean cinema’s violent, psychologically unsettling, globalized, masochistic, even remasculinized temperament, something this cinema shares with the narratological features of contemporary Hollywood from the 1990s (i.e., Fight Club, 1999), but it also speaks toward this cinema’s affinity to critique the neoliberal political economy in South Korea. Park does so through sophisticated nonlinear storytelling that cultural theorist Rob Wilson perceives “is sublime in the technical sense, meaning it confronts traumatic and underrepresented materials haunting the Korean social system of capitalist global modernity.”16 However, with an increase in personal autonomy, much civic and artistic dialogue becomes muted for the spurious, messy, and constraining end goal of corporate capital, which accommodates the agenda of neoliberalism in South Korea. According to David Harvey and his evocation on capitalism’s constraints over culture, he sees “control over information flow and over the vehicles for propagation of popular taste and culture have likewise become vital weapons in competitive struggle.”17 For example, in Park’s SFMV, Kyu Hyun Kim misconstrues the film as being “unconcerned with the evils of capitalist exploitation,” yet, on the contrary, I see this particular film constructing a narrative about this very exploitation. These victims whose “refusal (or inability) to transcend [these] subjective perspective [do not] enter into communication with one another”; this happens because of two central symptoms of neoliberalism that Kim misses: self-reliance and reserved behavior that dictate antisocial communication amongst its characters.18 Thus, these symptoms rarely present any alternatives for its protagonists. And like the characters in Park’s SFMV, it is no wonder that the neoliberal agenda in an actually existing institutional context has made a creative compliance to apolitical critiques like Kim’s all the more prescriptive for the time. Whereas noteworthy now, due to the financial crisis in 2008, several years ago labor representation, and its agitator, neoliberalism, was not even a marginal concern in film studies. The disapproval for this (Marxian) theoretical perspective explains why little has been written on Park’s labor fascination, except in a pejorative context. Another example presents itself, where South Korean film scholar Chong Song-il’s tagline “Skulking Stalinism” typifies the gamut of reviews on SFMV appearing after the film’s release in 2002. Chong’s neo-formalist criticism incorrectly conflates Stalinist bureaucratic authoritarianism as a Marxist-Leninist understanding of class, a linguistic turn of phrase that does not differentiate what Stalinist regimes did to labor throughout history (from Gulag labor camps to harsh labor discipline). In other words, Chong sees Park’s polemical vision in SFMV as less relevant in his mode of auteur criticism—instead he gives precedence to other Korean filmmakers by focusing on their use of strict aesthetic processes rather than tackling the domestic dissension and strife that is pivotal to Park’s raison d’être. In regard to Kim and Chong’s rigid sentiments, I would like to present several new critical inquiries that do not dismiss Park’s socially conscious tendencies out of hand but instead embrace his films as a type of politically committed (filmic) literature.19

Following this logic to rethink the extreme management of the lower classes, identity also becomes an issue for other theorists working on Park’s films. Joseph Jonghyun Jeon points to market entitlement over the preference and security labor once held, yet moves to focus on traumatic impulses as they pertain to contemporary South Korean identity. Taking up other scholars’ work on South Korean cinema in what he calls “an allegorical pulse” in Oldboy, Jeon theorizes the symptoms and repression of pain in postmodern Korea.20 Through a psychoanalytic framework, guided specifically by a Derridean notion of “residual selves,” he questions “the foundations of a national imaginary and, hence, its future” after the loss of Korean Confucian capitalism during the financial troubles of the late 1990s.21 However, Jeon’s other interest is the supremacy of the once communitarian-oriented chaebols, eloquently positing that under new IMF measures these family-owned corporations were forced to lay off both factory workers and salarymen, “a breakdown of corporate paternalism, demonstrating … just how different a chaebol was from a family.”22

Interestingly, these changes provided exemption for some smaller groups of neoliberal elites and their family-run chaebols in exchange for their compliance in the renegotiation of a harsher, more hostile environment for South Korean labor. Despite chaebols being mentioned at some length by leading film scholars, discussions have centered exclusively on investment practices in the Korean film industry or neoliberal cultural policies.23 However, I wish to call attention to this condition that I label the neoliberalization of chaebol culture as it seeps into popular cinema from South Korea, with a focus on the appearance of the chaebol in both SFMV and Oldboy. One scholar who recognizes the strong neoliberal nature of chaebols after the financial crisis is Sonn Hochul, who avers:

Neoliberal globalization, thus, has resulted in internal fractures within the Korean ruling bloc. In contrast to their full support of neoliberal labor policy intended to enhance labor flexibility, chaebols have vigorously opposed reform measures that have been targeted at them, including regulations on investment and management restructuring.24

Although the previous ruling bloc in South Korea was rapidly dismantled and was then quickly consolidated after mergers, acquisitions, and bankruptcies of the less ‘proactive’ chaebols to venture capital firms, the new ruling bloc that emerged was highly mobile and versed in union-busting tactics. These neoliberals advocated a transnational stance for the absolution of free market supremacy, influenced by the “Big Five” U.S. business schools (Wharton, Harvard, Stanford, Sloan, and Kellogg), whose ethos for instituting newer means of labor exploitation was the favored method in the more competitive and unforgiving globalized environment. In Oldboy, for instance, Lee Woo-jin, one of the central protagonists of the film and a successful venture capitalist, is found discussing hostile mergers over his mobile phone as if these financial exchanges happen daily, unfazed by such transactions yet calculating in his role as corporate raider. Presumably, his business school training in the United States exemplifies both a Friedman-esque penchant for business dealings along with his endless access to capital due to his wealthy upbringing, which explains his large property holdings around Seoul. Guided by such themes, Park Chan-wook takes as his subject the disjuncture pitting labor and the middle classes against the elites. Lee Woo-jin can be interpreted as a callous figure in Oldboy, transnational in his outlook, and basking in the rhetoric of most neoliberal CEOs who came to believe in a “masters of the universe” mentality at this time.25 Although there is some resistance to the wealthy executives in Park’s films, figures like Woo-jin eventually come to subjugate the sometimes docile, sometimes ferocious, service industry worker.

Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance

SFMV revolves around Ryu (Shin Ha-kyun), a green-haired deaf-mute laborer whose layoff from the chaebol firm Ilshin Electronics culminates tragically for him and the firm’s nouveau riche owner, Park Dong-jin (Song Kang-ho). The film opens with a medium close-up of a female radio personality in Seoul reading a letter from a listener, a declaration of a strong work ethic by an unknown resident in Seoul. We learn it is Ryu stating in his letter: “I’m a good person … I’m a hard worker.” (These sentiments are later challenged in the film on moral grounds.) Moving from radio studio to hospital rooftop, there is a cut to a close-up of Ryu and his terminally ill sister listening to this radio show above her patient ward where she is being treated for renal failure. The letter also reveals Ryu’s selfless work ethic to pay his sister’s exorbitant medical bills in Korea’s skyrocketing private health-care system. The brother and sister bond is further established by the memories we hear from the radio voice-over, which complement a delicate watercolor postcard of their childhood vacation spot. A mawkish impressionistic image of a nondescript riverbed outside of Seoul, it remains one of the only joyous images in an arc of despair and estrangement throughout the entire film.

In this context, the watercolor postcard also connotes an auratic impulse for labor and for familial relationships as unique social and psychic modalities of postmodernity. If we bring in Gramsci’s ideas of the organic body of labor, it relates well to the uniqueness of Park’s auratic sentiments regarding the representation of the worker in his film. Indeed, the laborer and their livelihood to Park is a heterogeneous thing, posited as such through the example of Ryu and his sister in SFMV, working-class figures that embody one of the multitude of stories in the global proletarian class in East Asia. In other words, what Gramsci saw as a “human community within which the working class constitute itself as a specific organic body” speaks to familial support in the social sphere, something Park is interested in developing (and tearing down) in SFMV.26

Put another way, the labor classes for Gramsci were comprised of men united by their commonalities, through which their goal was either the production of goods or the regulation of these goods that determined and conceptualized their pecking order in public life. Whereas the laborer for Park is also an organic thing—organized around his or her physical toil that then produces a commodity object—he also sees the laborer at the service of market. Yet Park constructs his laborer cinematically as one susceptible to pain, devaluation, and, to echo Marx, “abstraction,” which I will illustrate in the coming paragraphs.27

Eventually put in a state of constant decomposition because of the corruption and exploitation of capitalist policies, this watercolor postcard resonates on-screen as a kitschy portrait of society that does not exist in neoliberal Seoul, and is nothing more than material abstraction, meaningless except to Ryu. Nonetheless, Ryu’s sentimental gesture in sending the watercolor postcard to the radio station keeps his sister’s morale up (she even weeps), an early example of his unwavering commitment to her unlikely rehabilitation. Preceding this introductory sequence, we learn of her release from the hospital due to unpaid kidney treatment, and she spends her nights writhing in agony on their cramped living room floor in Seoul. Days after Ryu’s sister’s release he is in search of a donor with the proper blood type for a transfusion and kidney transplant. Unexpectedly, however, he is laid off from the electronics firm where he works as a metal founder. Despondent and unskilled in other trades (although it is revealed that he dropped out of art school to care for his sister), Ryu comes across, while wandering Seoul, a fly poster advertising organs for sale. He decides to sell his own kidney in exchange for a match with his sister’s, enlisting the dubious services of black-market medical financiers. At a clandestine meeting in a semi-demolished building shot in semisilhouette as Ryu and two thugs ascend the stairs of a wall-less building, he agrees to the open-air surgery.

After the operation and waking from the anesthesia with one missing kidney, he finds himself the victim of organ-selling pimps. This scene represents the real-life practice of organs circulating as a medical commodity in the Pacific Rim, a brand of neoliberal price gouging wherein the endgame is selling Ryu’s kidney to the highest bidder. Black-market organ selling should also be seen as a consequence of skyrocketing health care in South Korea, where the marketization of individual patient care has become an institutional norm. This has made possible, to cite Rob Wilson, “a system in which body parts like kidneys and hearts become commodities for which one either pays or else dies.”28 Similarly, labor in SFMV is much like the organ selling market, too, as it becomes a cheap commodity for the elite to buy and sell. The film goes on to develop this notion where Ryu and his compatriots are nothing more than disposable producers of goods, organ harvesters or ‘fall guys’ for complex traumas that relate back to capitalism’s unequal social determinism on class through its economic development in the region.

Returning to the film, Ryu, desperate after losing both his kidney and his ten thousand won of severance pay to the organ traffickers, brainstorms with his leftist girlfriend, Yeong-mi (Bae Doona), and then begrudgingly scheme to kidnap his ex-boss’s daughter, Yu-sin. They rationalize this decision in the hopes of saving his sister with the ransom money that Dong-jin will pay for his daughter’s safe return. But after the successful abduction of Yu-sin, Ryu’s sister learns of his termination at Ilshin Electronics, finding the pink slip in his pocket. She then commits suicide, guilty and despondent that Ryu would perpetrate such an unspeakable act, and understanding that she is his financial burden. Gripped with anguish after finding his sister’s bloodless body in the bathtub, Ryu travels outside of Seoul to bury her by their childhood vacation spot brought to life filmically by Ryu’s watercolor postcard from the opening of the film. The delicate watercolor is now a neoliberal burial ground, the earlier image transformed into a garish and jarring visual epitaph. Both film image and watercolor postcard become sites of misery, trauma, and death.

Bored and then accosted by a vagrant wanderer while she tries to sleep in Ryu’s car, Yu-sin runs in a panic from the disturbed man toward Ryu, where she slips and drowns in the mountain stream. The grief-stricken Ryu, busy burying his sister, never hears her screams for help as she floats by in the river. Following the death of his daughter, Yu-sin, Dong-jin hunts down Ryu and his anarchist girlfriend. Finding her first, at home in her apartment, Dongjin ties her to a chair and tortures her through electrical shocks to the head, killing her in reprisal for his daughter’s death. By the end of the film Ryu has been caught by Dong-jin after a deadly game of cat and mouse. Slashing his ankles and bleeding him to death in the same river where his daughter drowned, Dong-jin then dismembers him onshore. But shortly, Yeong-mi’s radical group finds Dong-jin and, in retribution for Yeong-mi’s murder, stab him viciously to death. SFMV thus concludes with all of its characters succumbing to fatal and calculative exploitation under neoliberal restructuring, forcing many actions otherwise unthinkable in more equitable times. We learn, for example, that Dong’s chaebol firm was sold off—presumably to a stronger conglomerate chaebol. No doubt as ceaseless accumulation suspends time, mourning, loyalty, familial and emotional ties, neoliberalism remains the only stable variable in Park’s storytelling, a capricious thing that I will examine in more detail in the following sections.

Close Analysis of Sfmv

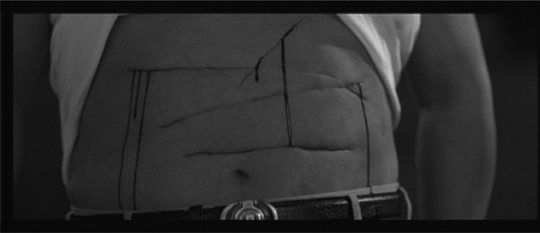

Park Chan-wook’s ability to meticulously mine the effects of neoliberalism on South Korean society is uncanny. Out of his troubling images comes sociocultural meaning, often producing less trenchant class criticism than one would expect. For example, in one striking scene in SFMV, a newly redundant welder named Peng throws himself in front of his exboss Dong-jin’s SU V; the incident occurs as Dong-jin is on his way back with his daughter and colleagues from lunch at the American chain restaurant T.G.I. Friday’s. Dong-jin leaps out to see who he has struck and finds Peng clutching his right leg. Dragging himself out from underneath the SU V, now several meters down the residential road dotted with Western-style McMansions, Peng proclaims his terrible luck since his layoff: “My wife ran off. And my kids are starving.” There is a palpable uncertainty as to what he will do next. Disheveled, he pulls something from his coat, throws down his union fatigue jacket, and lifts his white T-shirt (see Figures 11.1 and 11.2). He then begins mutilating his body by carving ceremoniously into his midriff with a box cutter. Dong-jin and his chaebol partner initially watch in disbelief, then horror, until finally running to grapple with Peng over the box cutter as the self-mutilation continues to take place. But this action seems more out of self-preservation for Dongjin’s daughter and his colleague’s wife and child than for restraining his ex-employee from doing any further bodily harm.

Figure 11.1 The proletariat Jing confronts his chaebol boss Dong-jin with a box cutter, demanding an explanation for his recent termination.

Figure 11.2 Learning he will not be re-hired, Jing maims himself with the box cutter as a symbolic and sadistic gesture of his own despondent state.

This scene is shot from the point of view of Ryu, also recently laid off, who is waiting in a nearby car and plotting the kidnapping of Dong-jin’s daughter with his girlfriend, Yeong-mi. A long shot positions Ryu in such a way that the viewer does not empathize with this act of physical desecration by the laborer but instead as questioning whether their kidnapping plan will work with all this sudden attention brought by Peng. In many ways, this scene finds a corollary with Gramsci’s description of the turbulent time in Italian history, after the Great War, when workers started to become an indifferent mass, often resorting to violence and crime. These workers lacked a “clarity and precision to form a workers’ consciousness” when social movements at this time were weakened by capitalist consolidation of factories and worker sentiments for equality waned.29 In similar ways, the contemporary workforce of Park’s neoliberal Seoul lacks the clarity and stamina to counter, or at the very least ability to challenge, the IMF’s restructuring. In the neoliberal present of Park’s South Korea, work is taken away and its employees are forced to pursue individualistic labor production, or more crudely, predatory action to attain and produce their own brand of capital (child abduction in this case, leading to monetary ransom).

To enable looking at this sequence as a class differential, between the hegemon (Dong-jin) and the consenter (Peng), Gramsci surmises a universaltype treatment of the worker under different capitalist conditions in the early twentieth century, “where the worker is nothing and wants to become everything, where the power of the proprietor is boundless, where the proprietor has power of life and death over the worker and his wife and children.”30 Peng represents this Gramscian notion in the mutilation scene where his corporeal self, his actual flesh, is at the disposal of the capitalist, Dong-jin. Aware of Peng’s specialized skills on the shop floor, yet unbothered by his use value, Dong-jin predetermines this sort of reaction: Peng turns to a sacrificial gesture to reassert his loyalty and labor value. However, Dong-jin is resolute in his decision to cut Peng form his chaebol organization.

Here, Park also highlights the sharp division neoliberalism creates, using costumes to show such disproportionate prosperity (avoiding direct ideological alignment with the worker). He creates the “boundless power of the proprietor” in an action that is reinforced by attire. Dong-jin is presented in the diegesis as driving a new Korean-built Ssangyong SUV; he wears designer clothing and Oakley sunglasses; eats at expensive American chain restaurants; buys his preschool-age daughter a mobile phone, talking doll, and fashionable dresses; lives in a contemporary-style home in Seoul; and owns a once successful company. Peng wears the clothing he works in daily; does not drive but rather uses public transportation; provides the bare essentials for his children; and lives in a squalid, ramshackle, two-room shack on the southeastern periphery of Seoul known as Bongcheeon district (or more dubiously ‘Pig Village,’ “jammed between a high-rise development and an expressway … [and] home to about 3,500 people”31). This temporary housing site operates in the film as another class differential, where after Dong-jin’s daughter is kidnapped he searches out the obvious suspect, Peng, there, only to find he and his family poisoned in their filthy surroundings. Important to the narrative, and in accordance with Park’s social criticism, the dwelling becomes another means to measure survival and economic supremacy in the faltering Tiger Market.

Finally, this mutilation sequence in Park’s film is remarkably politically conscious without being didactic. In many ways, labor in SFMV begins to cooperate in its own demise. Yet these expressions of neoliberalism’s effects on the working classes in South Korea are what others have called a distinguishable “allegorical gesture … [which] turns politically loaded cinematic motifs into signs that are intelligible without an understanding of their historical and cultural contexts.”32 The desperate move on the laborer’s part illustrates his loyalty to the chaebol firm, but his audacity is ultimately an act of ill-fated retribution for his redundancy. In a guttural tone, Peng screams out: “I gave my youth to Ilshin Electronics.” His pride in his nearly perfect error rate as a metal welder (“only .008 were faulty goods”) and at not having taken a sick day in six years points to a different economic time, before post-IMF Korea. Although Peng’s remarks further illustrate his mastery of his trade, they also concretize Korea’s disregard for skilled workers in this climate of economic consolidation. Hence, this disturbingly competitive environment also signals the desperation of the worker to remain employed at this time in South Korea.

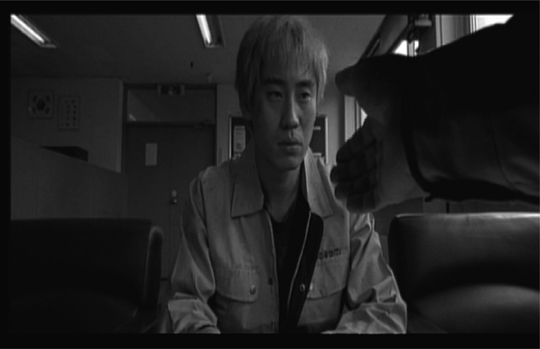

In another crucial and plot-changing scene we see Ryu exerting pure energy on the shop floor of Ilshin Electronics (see Figures 11.3 and 11.4). This sweaty and tactile scene corresponds to Ryu’s daily routine: he is responsible for the continuous molding of metal brackets, labor that is painful to watch because of its banality and maddening repetitiveness. However, Park here also structures a visually dense and mesmerizing mise-en-scène that pays homage to the simplicity and physical strength this type of material work requires. Shot in a mostly muted and washed-out color palette outside of the factory, inside the factory we find a scene awash in deep colors from the white-hot orange-yellow flame from the opened furnace to the sweaty and blanched workers’ bodies that shuffle around the shop floor. Against these brilliant and saturated warm colors, Park contrasts the deep umbers of the factory walls, grayish concrete furnaces, and olive-colored machinery, masculine imagery undoubtedly in line with a proletarian-style mise-en-scène.

Figure 11.3 Ryu labors arduously on the factory floor to support himself and his ailing sister.

Figure 11.4 The victim of downsizing right before the firm’s financial collapse, management pitilessly sacks Ryu, taking the neoliberal stance: management first.

There is then a medium close-up of a toned and slightly gaunt Ryu, who stands in front of a metalworks furnace and guides hundreds of amber, glowing, molten metal pieces into a waiting wheelbarrow. He then transports this white-hot aluminum across the factory floor, where it is cooled in a water basin, taking on its eventual hardened form. Presumably, this activity is repeated dozens, possibly hundreds, of times in a given shift by Ryu. From here, this action then abruptly cuts to the firm’s office block, which is composed in lifeless opposition: an administrative wing filled with cubicles, pale and colorless office furniture, and staff wearing indistinguishable blue and gray suits. Park adds to the generally sterile look of the office—arranged in a visually acute way—how these two different spaces create a dialectical image. Park’s use of the office is in striking aesthetic and material opposition to the shop floor; its vapid corporate operation lacks the intensity of the material-based work and what Gramsci would consider “organic structures of production.”33

Park’s purposeful juxtaposition and contiguous editing of these two scenes enables the audience to sympathize with Ryu as he learns of his termination, instantly changing his livelihood from ceaseless material toil on the shop floor to inert unemployment (and later to criminal behavior, unspeakable violence, corruption, and finally homicide). Again, Gramsci’s thoughts reveal a process of capitalist social reality in relation to this scene: “The worker is, then, naturally strong within the factory, concentrated and organized within the factory. Outside the factory, in contrast, he is isolated, weak and out on a limb.”34 One could interpret Ryu as a contemporized Gramsci laborer—indeed out on a limb—whereby this scene chimes with the privatization of human interest that is geared toward a survival of the fittest amongst firms as well as human beings in Seoul. A fictional scenario where labor is victim to market forces and unattainable profitability that could have just as easily taken place in Turin or Rome in the 1920s under another variation of capitalism. Moreover, this scene connotes in a powerful way the dialectical image as historically timeless, a cinematic technique that decodes and deconstructs various modalities of the world market in Seoul and elsewhere, and a filmic technique Park returns to often.

In other words, Park in this film fabricates much of the real-world issues surrounding neoliberalism in South Korea, structuring an aggressive and unforgiving filmic space that is miserable, claustrophobic, and dystopic but by “no means a postmodern nihilist” diatribe on unmotivated sadism in an age of neoliberal peril as some have accused.35 This expendable public sphere, as represented in this scene through Ryu’s termination, could be said to mirror the attitudes that management shows toward labor more generally. Terms like synergy, downsizing, and consolidation of labor can easily be applied to this scene as the disregard by management in this context adopts a calculated business school ethic, a neoliberal attitude to labor, finding these proletarian classes uncivilized and ultimately noncompatible instruments in a firm’s bottom-line agenda. Yet even at an almost primal level, this scene, through its deliberate and corporatized mise-en-scène, equates a stolid mind-set and space; suggesting that human compassion is concealed for the illusory sense of profitability in the newly managed chaebols like the one seen here in SFMV.

Such an attitude is only compounded as the unnamed manager is rushed off to an off-site lunch, utterly unconcerned with his firm’s decision to lay off Ryu and what he will do next. In this respect, neoliberalism’s erasure of social safety nets in South Korea is thus magnificently composed in this sequence. Alluding to the dubious and “inadequate” welfare system, widespread unemployment, and unraveling social fabric suggests that, in economic terms, the free market has transformed Korean citizens into what Hsuan Hsu calls “disposable people.”36 These neoliberal attitudes come to devalue a Confucian lifestyle as seen through the more sadistic actions of these central characters.37 Yet, by the end of the film, we learn that it is both management and labor that pay the price, losing loved ones to neoliberalism’s harsh economic imperatives that cyclically determine the gruesome fates for all of Park’s characters (by suicide, drowning, electrocution, dismemberment, and ordered execution).

Oldboy

In Oldboy one finds something more financially insidious. The film builds on a complex narrative, centering in a structural (though not necessarily visual or narratival) way on elite technocrat Lee Woo-jin (Jitae Yu) and his unflinching power in neoliberal Seoul. Woo-jin is a character that can be seen as “venal, grasping and perverse,” to echo Gramsci, and he is determined not to direct all of his energy to achieving economic success, which he already has plenty of, presumably through his chaebol family connections. Rather he is dually motivated by revenge.38 The social and psychic control he wields, in the way of a fifteen-year-long imprisonment imposed on his target, petit bourgeois class member Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik), only tangentially connects to Dae-su’s high school rumor that Woo-jin and his sister Soo-ha were incestuous lovers. Dae-su, through a flashback near the end of the film, is reminded of the sexual liaison between these two siblings, peering through a cracked windowpane, finding them in a tender yet compromising embrace.

Putting the blame on Dae-su for his beloved sister’s suicide, Woo-jin’s vengeful plan moves beyond the civilian garrison where Dae-su must toil away his time: keeping detailed journals of all the people he had scorned and dishonored in his lifetime, training himself as a competent fighter through shadowboxing, while digging a continuous hole in the cell/room’s wall with a metal chopstick mistakenly included (or perhaps given) in one of his daily dumpling meals. This intellectual and physical work occupies one-half of a split screen in this particular sequence where a series of images from the television are juxtaposed with Dae-su’s busywork in his cell-like room. The images on the right of the screen follow the temporality of the Korean present tenseness and its spectacular contemporary history, all over a decade and a half of forced detention. One finds a televisual reel of political and cultural development next to national scandals and the always elusive reconciliation with North Korea. Here, one could observe Dae-su’s countless hours of televisual consumption as both disparaging as well as enlightening. Park uses this dialectical strategy to deploy an artificial sociohistorical reality, differing significantly from SFMV. This artificiality creates a parallel split screen for viewers—on the left of the frame a temporal ‘real’ reality of Daesu’s lived experience in forced confinement (physical toil through his training and digging through the wall and material production in the form of his diaries of personal history)—whereas on the right of the frame there is an appropriated construction of a linear breaking news template from South Korean media (where scrolling images of Korean political corruption to the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to China to the death of Princess Diana and, most importantly, the IMF bailout are chronologically displayed). Here, television serves as a mode of distraction given to Dae-su by his captors, which also reminds him of his seemingly unending incarceration. But this split screen image also structures the “where and now” of South Korea, part of a spectral world with its own cells and walls that demand, much like Dae-su’s forced personal re-historicalization of his past—why he (and South Korea) might be forced into this current state of subservience. This can be read metaphorically as South Korea’s fragile economic recitation by larger global hegemons, mainly the IMF and U.S. investment and capital, which is just as important to think about as the local hegemons or wealthy neoliberals and the chaebols that also ratified South Korea’s historical trajectory. These intangible and tangible “glocal” forces require a careful historical reexamination, in and outside of Park’s diegesis.

Following this dialectical sequence, Dae-su is released from the private penitentiary, where, due to his hypnosis, he begins, unknowingly, an incestuous relationship with his long-lost daughter, who he finds working in a Sushi restaurant (this reunion is prompted by Woo-jin). Incest as a trope is handled by Park to equate a perversity and dissipation of familial values and patriarchal society spawned by a new set of neoliberal values, i.e., the victimization of others, lack of communal respect, and absurd self-motivation above the complex networks of capitalist classes. Hyangjin Lee, in her appraisal of Oldboy, sees the undercurrent of sexual perversion as a moral ambivalence towards incest that:

radically critiques Confucian patriarchal society, while connecting this critique back to antagonistic capitalist economic classes. The moral dilemmas faced by Woo-jin and Dae-su over their incestuous relationships are resolved in completely opposite ways. Woo-jin, the rich boy, abetted his sister’s suicide and escaped to America, setting up Dae-su as a scapegoat to relieve his sense of guilt.39

By successfully facilitating Dae-su and his daughter’s sexual encounter, Woo-jin (also in his position of economic supremacy) shapes the lives of the people beneath him: he pays for the civilian prison where Dae-su is held, leaves money and clothes on his release, while also paying for his daughter’s upbringing and education in Dae-su’s absence. If Ryu in SFMV is the prototypical working-class Korean male, Dae-su in Oldboy embodies the other class hampered by immaterial labor and socioeconomic disadvantage, an easy target given his drunkenness, general bourgeois malaise, and reprehensible behavior as a salaryman. These social traits play savagely into Woo-jin’s planned revenge. The cyclical effect on the bourgeois males in Park’s fictional Seoul echo Gramsci’s thoughts in many ways with his very same fascination with class, where: “Human society is undergoing an extremely rapid process of decomposition, corresponding to the process of dissolution of the bourgeois State.”40 Because of this deterioration and an expendable middle class under neoliberal globalization, new spaces for such exploitation occurred in Italy, according to Gramsci, but can also be found in Park’s Oldboy.

Control is also key to Oldboy’s narratological development. And to bring Gramsci back into the discussion, I believe his work on state power, particularly the role that police played, is vital to understanding Italy during the 1920s. In this period, they adopted disreputable practices to suppress worker solidarity and revolt—through brutal force, infiltration of union organizations, disinformation, and general arrest. Whereas in Park’s contemporary South Korea, Woo-jin utilizes similar yet more technically advanced tactics to achieve authority. Driven by a warped reprisal to clear his own guilty conscience, Woo-jin masters several hegemonic modes of suppression. One can trace these modes of surveillance where Dae-su’s seemingly autonomous search for his captor is never out of Woojin’s grid of discipline. Dae-su is followed by for-hire neoliberal gangsters who perform various stakeouts of his movements around wider Seoul: Dae-su has his Internet browsing monitored, is gassed with his daughter in a hotel room (appraised gleefully by Woo-jin), and eventually discovers a bug in the heel of his shoe, all clandestine forms of surveillance and eventual sublimation to Woo-jin’s scrutiny and social jurisdiction.

This discussion of surveillance leads me to my discussion of architectural forms. In other words, Oldboy’s mise-en-scène explores topography, in particular interior space, as essential to conceptualizing neoliberalism. Saskia Sassen has developed this notion elsewhere, finding that convergent modes of control discriminate different, usually lower-class urbanites. Sassen finds that “the interaction between topographic representations of fragments and the existence of underlying interconnections assumes a very different form: what presents itself as segregated or excluded from the mainstream core of the city is actually in increasingly complex interactions with other similarly segregated sectors in other cities.”41 Ultimately, Oldboy comes to expose the logic of social stratification and urban transformation via architectural mapping. Here, both tenets— class stratification and urban change—are thus analogous to the contradictions that neoliberalism urbanism has brought to South Korean society. The real and fictional cramped and jumbled city blocks of Seoul are what make such sectioning off of these different classes of society possible. Through Park’s interest in urban architectural space, the cityscape as a trope comes to display how Seoul has transformed in the post–Tiger Market neoliberal epoch, shared by geographers, who, like Park, have found that the:

propagation of neoliberal discourses, policies, and subjectivities is argued to have given rise to neoliberal urbanism. The neoliberal city is conceptualized first as an entrepreneurial city, directing all its energies to achieving economic success in competition with other cities for investments, innovations, and “creative classes.”42

Whereas many global communities experience such similar urban regeneration at the hands of neoliberalism, South Korea remains at the top of the list in terms of socioeconomic and physical changes to its urban fabric. Urban planning scholar Mike Douglass has argued that “missing from the neoliberal city [of Seoul] are unscripted public spaces, place— making by residents and their neighborhoods … lower income populations, and participatory planning.”43 He continues to see that despite the ideology of the private sector much public space has become a target for rezoning or worse. For example, because of the national financial crisis, families or family members were often forced onto the streets or pushed to districts like Bongcheeon as jobs became increasingly scarce. In Jesook Song’s fieldwork in Seoul, she characterizes different types of homelessness: females, families, individuals. In essence, she posits that during the Asian debt crisis females were no longer the “needy” subjects, whereas the “deserving” subjects, mostly out of work men, had been given preference “with the potential of returning to or creating normative families.”44 The oftentimes indiscernible victims became what Song calls invisible homeless women. Thus if neoliberalism indoctrinates these destructive and cutthroat social realities as it deterrorializes the metropolitan milieu, who or what imposes, even fortifies, such a reality?

In filmic terms, the neoliberal architectures of Seoul becomes a topographic chessboard where Woo-jin allows his opponent Dae-su to discover and mobilize his own revenge. Park’s cinematic imagery is conceptualized through smooth, almost styleless residential and commercial buildings that adorn Seoul, or “apartment city” as it is locally nicknamed. As if keeping some of the Eastern-European style, albeit socialist layer-cake designs, Seoul has contemporized its urban milieu with postmodern vertical designs that Park uses in his mise-en-scène: one finds concrete replacing brick, tablets of colored glass replacing plastic or wooden window frames, and dark, drab exterior surfaces give way to more ornate building materials (light metallic skins and corporate logos for transnational banks, city bars and Korean characters in nonresidential areas that keep some of the provincial and vernacular customs intact). Architectural surroundings to Park are built spaces that buttress various stages of postindustrial power in Seoul’s neoliberal present. Therefore, we must also consider, through built spaces, access to both dilapidated and meticulously refined architectural surroundings that are repressive and powerful metaphors in Park’s filmmaking. In other words, these dwellings and domains come to expose the burden of continuous economic adjustment in Seoul.

Put another way, Park deals with architectural space and its relation to neoliberal urbanization in an observant and resourceful way. My brief close analysis will focus on the final sequence in Woo-jin’s penthouse apartment. In this scene, we find Dae-su, in a fit of rage after being taunted by Woo-jin, charge his nemesis, only to be confronted by Mr. Han, a gifted opponent with superior martial arts training. In a complicated series of shots, Park uses a “bird’s-eye view” of the exterior of the penthouse, eventually panning in on this violent scene of grappling, choke holds, and deflected bodies. Moving from an exterior, omnipresent position between residential high-rises and corporate tower blocks to a hovering tracking shot that penetrates through the penthouse floor-to-ceiling windows, the shot eventually returns to a pan of Dae-su, who, in battle with Woo-jin’s bodyguard, rests momentarily in the cavernous space of the penthouse. It is here that violence comes to parallel the effects of neoliberalism on society as the two jockey for position in the elite and often clandestine flows of power (both capital and psychic) that Woo-jin holds over Oh Dae-su and his employed bodyguard. Here the hegemony of the neoliberal’s prowess echoes this minimalist, albeit concrete, architectural form. The cosmopolitan space of this penthouse apartment, much like Woo-jin himself, is stoic and purposeful, altering the destiny of Oh Dae-su while also allowing him to navigate the spatial confines of the museumlike apartment.45 In many ways, the filmic tableau of the penthouse is equally haunting in a visual sense. Based on an atmospheric and corporatized cosmopolitanism, e.g., airy tech-tonics and colored plate glass windows, smooth gray concrete interiors that are reminiscent of Louis Kahn’s minimalist architectural designs, running-water installations in the floor (lit green from below), along with a mechanized monolith wardrobe that splits open into four sleek forms to reveal Woo-jin’s impeccable collection of clothing, these objects, ornate and immaculate in reference, show the material wealth of Park’s neoliberal elite. Yet this also points to the vacuous nature of neoliberal spaces only transposed, momentarily by personal affects (photographs by Woo-jin). When scrutinized further, these vintage photographs and nineteenth-century camera equipment appear as a referent to forms of historical documentation, mawkish and formalistic, what I see as clever reminders by Park to the falsity of the image as truth-object. Equally, these images hung about the polished cement act as commemorative keepsakes and snapshots of loved ones, which simultaneously equate forms of leverage that inflicts new and continuous forms of trauma (Dae-su finds his lover is actually his daughter, presented to him in a chronological photo album documenting her upbringing since birth; whereas Woo-jin uses his sister’s memory, drawn from aging photographs, to justify his vicious plan and as personal leverage to keep his suicidal thoughts at bay until he ultimately takes his own life). In essence, we see this ensnared reality of neoliberal urbanization in the confines of such empty architectural space, a larger placeholder, much like the photographs themselves for understanding the com-modified experiences of contemptible human behavior and numbing personal loss, all emotional histories that become surplus experiences under neoliberalism.

1. See Marcia Landy’s Film, Politics, and Gramsci.

2. For example, South Korea’s continuous rupture with material labor is sometimes trivialized in its mainstream media. It is quite common that labor is chastised for being unable to cope with economic change or accused of trying to impede Korea’s progress.

3. Dae-oup Chang, 2001, p. 199.

4. Ibid., p. 198.

5. See http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/korea_republic_e.htm.

6. With regard to the Korean War, see Bruce Cummings, 2009. On corruption, see, for example, S. Haggard and J. Mo, 2000.

7. Chang, 2001, p. 191.

8. Labor as subject in Park’s films parallels many of the real-life struggles for the Korean worker. For instance, the union uprising in 1987 to a decade later where, in 1997, Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU or Minju-nochong) successfully launched the first general strike in Korean history. According to labor sociologist Hagen Koo, “The strike mobilized some three million workers and shut down production in the automobile, ship building and other major industries. This was a move against the Kim Young Sam government, who planned to legalize layoffs in such a way as to enable Korean capitalists to introduce neoliberal flexible labor strategies” (Hochul 2007, pp. 163–96). From this strike, temporary gains were made for the workers and the KCTU.

9. Hyangjin Lee, 2006, p. 182. For more information on the Tiger Market crash, see CRS Report for Congress, “The 1997–98 Asian Financial Crisis” at http://www.fas.org/man/crs/crs-asia2.htm; or PBS Online NewsHour, “A Wounded Asian Tiger” at http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/asia/july-dec97/skorea_12-4.html. See also the World Socialist website, “Daewoo Collapse Threatens Further Financial Crisis in South Korea” at http://www.wsws.org/articles/1999/oct1999/kor-o08.shtml.

10. Sonn Hochul, 2007, p. 209.

11. Ibid., p. 205.

12. Ibid, pp. 209–210.

13. See Jinhee Choi and Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano, 2009.

14. Fredric Jameson, 2009, p. 98.

15. Rob Wilson cites the use of IMF-noir as a generic formulation by Jin Suh Jirn, who is working on his doctoral dissertation at the University of California at Santa Cruz.

16. Rob Wilson, 2007, p. 123.

17. David Harvey, 1990, p. 160.

18. Kyu-Hyun Kim, 2005, p. 115.

19. Kyu-Hyun Kim quoting Chong Song-il, 2005, p. 113.

20. Joseph Jonghyun Jeon, 2009, pp. 714 –715.

21. Ibid., pp. 718–719.

22. Ibid., p. 720.

23. See Doobo Shim, 2006; Darcy Paquet, 2005. For political economy of cinema and media, see Yong Jin Dal, 2006.

24. Hochul, 2007, p. 206.

25. This colloquial saying is common in Wall Street for those men that control the market control the world.

26. Antonio Gramsci, 1994, pp. 166–167.

27. Karl Marx, 1990, pp. 54 –85.

28. Wilson, 2007, p. 125.

29. Gramsci, 1994, p. 130.

30. Ibid., p. 164.

31. See http://www.newint.org/issue263/pig.htm.

32. Eunsun Cho, 2009.

33. Gramsci, 1994, p. 175.

34. Ibid., p. 252.

35. Wilson, 2007, p. 124.

36. Hsuan Hsu, 2009.

37. However, these actions are never provoked for psychic reasons alone (with exception to the black marketers who rape and kill for money and for fun), largely because they disregard emotional resonance in order simply to stay alive.

38. Gramsci, 1994, p. 151.

39. Lee, 2009, p. 130.

40. Gramsci, 1994, p. 105.

41. Saskia Sassen, 2003, p. 25.

42. Helga Leitner, Jamie Peck, and Eric Sheppard, 2007, p. 4.

43. Mike Douglass, 2008, p. 8.

44. Jesook Song, 2006.

45. We see this more generally throughout the film, where Woo-jin seems not to infringe on Oh Dae-su’s supposed rational choice. Rational choice inflects the totality of the neoliberal market in this context. Ultimately, the sites of architecture in Oldboy, some cosmopolitan, some not, work to zone off and cyclicalize Oh Dae-su to participant in disadvantaged groups and locations that are in the end governed by Woo-jin himself.

Bibliography

Chang, Dae-oup. “Bringing Class Struggle Back into the Economic Crisis: Development of Crisis in Class Struggle in Korea.” Historical Materialism 8 (Summer 2001): 185–213.

Chang, Sea-Jin. Financial Crisis and Transformation of Korean Business Groups: The Rise and Fall of Chaebol. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Cho, Eunsun. “Korean Cinema Bids Farewell to Its Allegorical Legacy—Reading Oldboy on the Global Scene.” 2009. http://www.xn—z92b2xf0sc7b.com/paper/view.html?search_info=unity_paper^1^1&no=50655534.

Choi, Jinhee, and Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano, eds. Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2009.

Crotty, James. “The Neoliberal Paradox: The Impact of Destructive Product Market Competition and Impatient Finance on Nonfinancial Corporations in the Neoliberal Era.” Review of Radical Political Economics 35, no. 3 (2003): 271–279.

Crotty, James, and Kang-kook Lee. “A Political-Economic Analysis of the Failure of Neo-Liberal Restructuring in Post-Crisis Korea.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 26, no. 1 (2002): 667—678.

Cummings, Bruce. The Red Room: Stories of Trauma in Contemporary Korea Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009.

Dal, Yong Jin. “Cultural Politics in Korea’s Contemporary Films under Neoliberal Globalization.” Media, Culture and Society 28, no. 1 (2006): 303–323.

Douglass, Mike. “Livable Cities: Neoliberal v. Convivial Modes of Urban Planning in Seoul.” Korea Spatial Planning Review 59, no. 3 (2008): 3–36.

Gramsci, Antonio. Pre-Prison Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Haggard, S., and Mo. J. “The Political Economy of the Korean Financial Crisis.” Review of International Political Economy 7, no.2 (2000): 197–218.

Harvey, David. The Condition of Postmodernity. London: Blackwell, 1990.

Hochul, Sonn. “The Post-Cold War World Order and Domestic Conflict in South Korea: Neoliberalism and Armed Globalization.” In Empire and Neoliberalism in Asia, edited by Vedia Hadiz, 202–217. London: Routledge, 2007.

Hsu, Hsuan. “The Dangers of Biosecurity: The Host and the Geopolitics of Outbreak.” Jump Cut 51 (2009): pp. 1–3 (long online webpages).

Jameson, Fredric. The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings on the Postmodern, 1983–1998. London: Verso, 2009.

Jonghyun Jeon, Joseph. “Residual Selves: Trauma and Forgetting in Park Chanwook’s Oldboy.” positions: east asia cultures critique 17, no. 3 (2009): 713–740.

Kim, Kyu-Hyun. “Horror as Critique in Tell Me Something and Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance.” In New Korean Cinema, edited by Chi-yun Shin and Julian Stringer, 106–116. New York: New York University Press, 2005.

Kim, Kyung Hyun. The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.

Koo, Hagen. “The Dilemmas of Empowered Labor in Korea: Korean Workers in the Face of Global Capitalism.” Asian Survey 40, no. 2 (2000): 227–250.

Landy, Marcia. Film, Politics, and Gramsci. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994.

Lee, Hyangjin. “The Shadow of Outlaws in Asian Noir: Hiroshima, Hong Kong and Seoul.” In Neo-Noir, edited by Mark Bould, Kathrina Glitre, and Greg Tuck, 118–135. London: Wallflower Press, 2009.

Lee, Hyangjin. “South Korea: Film on the Global Stage.” In Contemporary Asian Cinema, edited by Anne Ciecko, 182–192. New York: Berg, 2006.

Leitner, Helga, Jamie Peck, and Eric Sheppard, eds. Contesting Neoliberalism: Urban Frontiers. New York: Guilford Press, 2007.

Marx, Karl. Capital Volume I. London: Penguin, 1990.

Palley, Thomas. “From Keynesianism to Neoliberalism: Shifting Paradigms in Economics.” In Neoliberalism: A Critical Reader, edited by Alfredo Saad-Filho, and Deborah Johnston, 20–29. London: Pluto, 2004.

Paquet, Darcy. “The Korean Film Industry: 1992 to the Present.” In New Korean Cinema, edited by Chi-Yun Shin, and Julian Stringer, 32–50. New York: New York University Press, 2005.

Park, Seung Hyun. “Korean Cinema after Liberation: Production, Industry, and Regulatory Trends.” In Seoul Searching: Culture and Identity in Contemporary Korean Cinema, edited by Francis Gateward, 15–36. New York: State University of New York Press, 2007.

Restivo, Angelo. Cinema of Economic Miracles: Visuality and Modernization in the Italian Art Film. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002.

Sassen, Saskia. “Reading the City in a Global Digital Age: Between Topographic Representation and Spatialized Power Projects.” In Global Cities: Cinema, Architecture, and Urbanism in a Digital Age, edited by Linda Krause, and Patrice Petro, 15–30. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2003.

Shim, Doobo. “Hybridity and the Rise of Korean Popular Culture in Asia.” Media, Society and Culture 28, no. 1 (2006): 25—44.

Shin, Jang-sup, and Ha-Joon Chang, eds. Restructuring Korea Inc.: Financial Crisis, Corporate Reform and Institutional Transition. London: Routledge, 2003.

Song, Jesook. “Family Breakdown and Invisible Homeless Women: Neoliberal Governance during the Asian Debt Crisis in South Korea, 1997–2001.” positions 14, no. 1 (2006): 38—63.

Vacche, Angela Dalle. The Body in the Mirror. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992.

Wilson, Rob. “Killer Capitalism on the Pacific Rim: Theorizing Major and Minor Modes of the Korean Global.” Boundary 2 34, no. 1 (2007): 115–133.