Neoliberal Rationality and the Films of Jeffrey Jeturian

Committed to exposing the ways in which the personal is always crosshatched with the social and the political, filmmaker Jeffrey Jeturian’s most memorable work traces the relentless conversion of all forms of social experience into economic transactions. In interviews, the Filipino film director has distilled the essence of his feature films: “personal, intimate stories that say a lot about our social and political realities,”1 resulting in an oeuvre that offers a sustained consideration of commodification: the commodification of sex (in Pila Balde [Fetch a Pail of Water], 1999), of traumatic life histories (in Tuhog [Larger than Life], 2001), of love (in Bridal Shower, 2004), of news reportage (in Bikini Open, 2005), of death, grief, and hope (in Kubrador [Bet Collector], 2006). Asked to comment on the thematic of commodification in his films, Jeturian has remarked that such transactions reveal of relations of exploitation and oppression.2

This chapter explores the relevance of Wendy Brown’s notion of neoliberal rationality—a “conduct of conduct” in which subjects internalize their subjectivation as entrepreneur-citizens—to the films of Jeffrey Jeturian.3 Brown contends that neoliberalism is more than a series of economic processes; rather, it is a suffusive political rationality, a form of governmentality that reaches beyond the state and the economy to pervade every sphere of life. “Neo-liberalism carries a social analysis,” Brown writes, which “reaches from the soul of the citizen-subject to education policy to practices of empire.” For Brown, the Foucauldian concept of governmentality underscores the role of internalized mentalities and calls our attention to how citizen-subjects are formed under neoliberalism, as opposed to being controlled, repressed, or punished.4 The logic of the market encroaches on every sphere of life that might be considered independent of economic calculation and hollows out, in the process, moral and ethical principles—like social justice and egalitarianism—that are not rooted in market logics of profit, pragmatism, or expediency.5 Though the commodification of affect and experience seems encompassed by the classical Marxist theory of reification, Wendy Brown suggests that the newness of neoliberal rationality lies in its capacity to “reach beyond the market.” Under neoliberalism, “all dimensions of human life are cast in terms of a market rationality.” Market values permeate even noneconomic spheres, reframing the state as a market actor and reaching even the most individuated scale of personal life. For Brown, neoliberalism is no mere aggregate of economic policies; instead, it is a political rationality that “involves extending and disseminating market values to all institutions and social action.”6

Whether in Pila Balde, where sex is linked as much to emotional devastation as to economic desperation, or in Kubrador, whose bet-collecting protagonist translates every experience into numbers that can be played for money in the underground gambling trade jueteng, Jeturian’s films manifestly thematize the neoliberal transformation of social individuals into calculative entrepreneur-consumers. The neoliberal formation of the national subject and the corresponding transformation of the public sphere have been chillingly described by Brown as “the production of citizens as individual entrepreneurial actors across all dimensions of their lives [and the] reduction of civil society to a domain for exercising this entrepreneurship.”7

Through a close consideration of Pila Balde and Kubrador, this chapter traces two levels at which both films operate to expose the workings of neoliberal rationality in the Philippines. First, Jeturian’s diegetic elaboration of commodification in story worlds where sex, longing, death, and grief become subject to economic calculation. Second, the extra-cinematic dimensions of Filipino film production in the context of economic crisis and political corruption. Released in 1999, Pila Balde’s conditions of production register the aftershocks of the economic collapse of Asia’s so-called “tiger economies” in 1997, when neoliberal tenets led to financial crisis in Asia.8 Intended to shield national industries from financial stresses and to foster global competitiveness, the economic and cultural policies that followed the 1997 crisis had unforeseen effects on-screen. My consideration of Pila Balde, a low-budget pito-pito film, indexes the desperate measures Philippine film studios adopted to weather the “crisis of Philippine cinema” in the late 1990s, when the “steadily dropping box office returns of Filipino films, the currency devaluation brought on by the Asian economic crisis, and prohibitive government taxation (with 30 percent of a film’s profits going to the national amusement tax) caused the industry to flounder against the ticket sales of Hollywood fare.”9 Seven years later, in 2006, Kubrador was released in the wake of another sequence of state crises: the political scandals of 2005 that implicated the First Gentleman of the Philippines, Mike Arroyo, in payoffs from the illegal gambling trade, jueteng.10 Prominent jueteng scandals recall not only state failure under the regime of Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (2001–2010), but also indict the prior administration of President Joseph “Erap” Estrada (1998–2001), whose ouster by mass protests in 2001 was triggered by the revelation of huge jueteng payoffs to the nation’s highest leader.

Whereas both diegetic and extra-cinematic aspects of Pila Balde and Kubrador illuminate the workings of neoliberalism in the Philippines, my chapter also wrestles with the question of affect or tone in both films. Jeturian’s films consistently feature slum dwellers and the urban poor, but Jeturian has repeatedly stated his refusal to romanticize poverty through melodrama, preferring “simple social realist stories”11 instead:

My quarrel with local films is that they usually romanticise or dramatise poverty—which is not the way Filipinos look at poverty. I myself am amazed at the disposition of the Filipinos. They enjoy life and that’s what I wanted to capture in my film. Not even poverty can stop them from loving, from keeping on [with] their struggles, from living, and I hope that is clear in my film because in the end, the message is, even if there’s so much tragedy in the lives of these people, life still goes on for them.12

The result is a diegesis that mingles desperate, immiserated economic circumstances with an absence (at least on the part of the protagonists) of utter despair, in large part due to a communitarian ethos of reciprocity that tempers the neoliberal formation of unimpeded individualism. In the last section of this chapter, I consider the tonal complexity of Jeturian’s films in the context of the proximity between gambling and death in his story worlds. Literal and figurative links between placing a bet (kubra) and giving a donation to those in need (abuloy)13 are introduced in Pila Balde and intensified in Kubrador.

Pito-Pito Filmmaking and Neoliberal Crisis

The neoliberal policies of the IMF and the World Bank laid the ground-work for financial crisis in Asia.14 The 1997 Asian economic crisis stemmed from capital market deregulation that encouraged a rapid influx of investment, fueling a property and construction boom in Southeast Asia that ended in loan defaults, retracted investments, and currency devaluations. As Jamie Morgan reminds us, “not only did neoliberalism help to create the conditions for financial crisis, but market liberalization helped to ensure that those conditions could be exploited.” Southeast Asian currencies—the Thai Baht, the Philippine Peso, and the Indonesian Rupiah—were famously raided by currency speculators like George Soros, who, through planned and systematic sales of Southeast Asian currencies, knowingly destabilized those currencies and then exploited the difference between fluctuating exchange rates, making millions of dollars in profit with impunity. In her acute recounting of neoliberalism as the stage setting for the Asian economic crisis of the late 1990s, Morgan notes: “The point is that neoliberalism provides incentives for the destabilization of an already precarious position. Neoliberal finance is the modern form of usury.”15 The supremely rational-calculative self-interest of a few resulted in lasting hardship for the vast majority of citizens in these economically battered Asian nations: the aftereffects of neoliberalism were registered not only in currency valuations and stock markets, but in the collapse of businesses and the further immiseration of the poor as the living standard for millions of people in Southeast Asia plunged below the poverty line in 1997–1998.16

Pila Balde bears the imprint of the cultural politics of pragmatism adopted by Filipino film and television studios in the aftermath of the 1997 crisis. The industry’s biggest film studio, Regal Films, strove to streamline costs, resulting in their infamous low-budget exploitation films, known colloquially as pito-pito. Literally meaning “seven-seven,” the phrase pito-pito denotes a Philippine medicinal tea composed of seven types of herbs. In the parlance of the Filipino film industry in the late 1990s, pito-pito came to refer to the films produced by Regal Films’ “ultra-low budget,” “quickie” division, Good Harvest, which, hoping to turn a profit in the brutal post-1997 economic climate, adopted an initial policy of completing each phase of preproduction, production, and postproduction in seven days apiece (in practice, these periods were somewhat longer), with tiny budgets and no bankable stars.17

Pila Balde was shot in thirteen days on a shoestring budget of 2.5 million pesos (about U.S.$50,000),18 a fraction of the twelve-million-peso budget then allotted for a typical mainstream Filipino film.19 The production limit of twenty thousand feet of film stock constrained the filmmaker to produce a good take with a shooting ratio of about two to one, as opposed to shooting ratios for high-dollar Hollywood films that may go as high as fifty-five to one.20 Remarkably, Jeturian recalls that Pila Balde’s climactic scene—in which a fire razes the slum community—was shot for only U.S.$500.21 Explaining his ability to mount such a complex scene so effectively and economically, Jeturian remarks: “I think my TV experience helped me when they gave me this pito-pito project. In TV you have to do everything fast, within a short time. You finish everything within two taping days. I thought it [pito-pito] was a breeze. Compared to two shooting days, suddenly I would be given ten shooting days!” The connection between pito-pito production and Philippine television was not limited to the role of television as a training ground for young Filipino filmmakers. Jeturian also recalls that in the late 1990s, Regal Films was contractually required to supply Philippine-based television network and multimedia conglomerate ABS-CBN with films for television broadcast. Pito-pito filmmaking became a way to produce films for television quickly and cheaply.22

In 1998, Marilou Diaz Abaya, a noted Filipina auteur who rose to prominence in the New Cinema of the early 1980s, characterized the beginning of the 1990s as a euphoric period of economic growth in the Philippines. An influx of investments allowed new movie theaters to be built and television and film studios to expand, and television became a profitable ancillary market for films after their initial theatrical release. Dollar remittances from overseas bolstered the formation of a new, more educated middle class who patronized quality films by established local directors. This era of growth came to an abrupt end with the Asian economic crisis of 1997. Shrinking profits panicked Filipino film producers, who could no longer rely on conventional filmmaking practices to ensure box-office success. Thus, for industry insiders like Abaya, the neoliberal economic crisis inadvertently created the conditions for a new generation of young filmmakers to revitalize the Filipino film industry at the end of the 1990s. Abaya noted that Filipino film producers “have no idea what will or will not make money. That’s very good for the filmmaker because, like the late ’70s and the early ’80s [the period of the Philippine New Cinema], they are forced to concede that the judgment on what will or will not make it is really the director’s.” Diaz-Abaya optimistically remarked that the crisis in Philippine filmmaking “all paints a picture of vitality” because “directors are being allowed to make films which five years ago would have been thrown out, because [producers] thought they had a formula, but not now.”23

Writing for Film Comment in 2000, critic Roger Garcia similarly regarded pito-pito filmmaking as a positive development. Garcia characterized pito-pito as low-budget genre filmmaking that, by “embracing a peculiarly Filipino mix of the lurid, political and religious … has produced some of the most promising mainstream films since the Seventies,” effectively “launch[ing] the careers of young filmmakers like Jeffrey Jeturian, whose hit, Fetch a Pail of Water (Pila Balde) has Brocka’s social conscience and a touch of humor.”24

Against these optimistic assessments of pito-pito film production, director Lav Diaz, hailed by Garcia as “the major writer-director talent” showcased by Good Harvest’s pito-pito division,25 gave a sobering account of pito-pito filmmaking’s exploitative conditions of production:

The idea that the “pito-pito” is a source of promise for Philippine Cinema is a myth. The only reason Jeffrey [Jeturian] and I were able to make meaningful films within this type of production is that we fought [the studio] all the way. The “pito-pito” is hell, from checks postdated to six months after the film shoot, to the lack of decent wages for the film crew—100 to 150 pesos [about U.S.$3] a day! It’s very exploitative. Sometimes the shoot goes on for 24 hours straight, with no sleep. People collapse from exhaustion. Far from keeping Philippine cinema afloat, the “pito-pitos” will make our industry sink to the very bottom. There is no redemption to be found in “pito-pitos.”26

Asked to comment on Diaz’s scathing assessment of pito-pitos, Jeturian responded by acknowledging the exploitative aspects of pito-pito filmmaking. Jeturian cited low wages, casting compromises, and creative decisions undermined by considerations of profit and expediency. Significantly, his comments shed light on the reliance of pito-pito filmmaking on the structure of abono—the act of advancing money to replace a shortage of funds or capital—that forced fledgling filmmakers to partially finance their own productions, with no assurance of recouping their investments:

The conditions of pito-pito are really exploitative in the sense that you have to make abono [advance your own money to cover funding shortfalls], you have to make pakiusap [ask favors] of everybody. They have to be your friends so they will agree to work under those conditions … You have to agree to casting actors who, even if they’re not [a good] fit for the role, you’re forced to agree with because they fit the budget … My feeling when I was doing my first film [Sana Pag-Ibig Na (Enter Love), 1998] was that it would be okay for me to make abono—to invest with my own money—because that’s what happens with pito-pito. Because of the limitations, you end up making abono for salaries of the staff. But for me, I saw it as an investment. Because it was a make or break thing for me. They [Good Harvest] gave me the break. Before that, no one would just give you a break and entrust five to ten million worth of investment unless you come from a rich family. Here in the Philippines there are directors who produce their own films just to get their break. So [to break into the industry], you either have to know the producer or have the resources to make your first film … That process gave me my break to do my first film. There was no deception. The studio will lay down their cards and say, “Here are the conditions.” And it’s up to you whether to agree or refuse. So if you agree then you should know what you are getting into and you accept the conditions.27

Jeturian’s candid portrait of the exploitative-yet-undisguised conditions under which young pito-pito filmmakers managed to launch their own careers in the Philippine film industry makes clear the neoliberal interpellation of the filmmaker-as-entrepreneur, forced to reify his own talent as a commodity in which to invest. As Lukács emphasized, reification entails the commodification of every worker’s own self-regard: “the worker, too, must present himself as the ‘owner’ of his labour-power, as if it were a commodity.”28 Self-objectification, or the sense of regarding one’s own qualities and abilities as objective possessions to be owned, disposed of, or properly invested in, is the condition of life under capitalism, one that intensifies as the structure of the commodity is interiorized and we regard our own labor in increasingly abstract, homogeneous terms (for example, as a “career”).29 Along with other conditions of constraint and compromise detailed earlier, pito-pito emblematized a reified structure of filmmaking in which talented directors were forced to “make abono,” to advance funds that in effect represented a form of investing in—or gambling on—their own careers.

Space, Class, and Entrepreneurship in Pila Balde [Fetch A Pail of Water]

In 1999, following Pila Balde’s strong performance at the box office, Good Harvest production chief Joey Gosiengfiao enthused: “It’s our first certified hit.” The first bona fide commercial success of pito-pito filmmaking, Pila Balde’s profitability upon its initial release was welcome news to a “local movie industry … experiencing its lowest dip in the business chart.”30 Impressively, Jeturian’s commercial hit went on to garner multiple awards and critical commendation both domestically and internationally.31

The material for Pila Balde originated in a television episode scripted for the weekly television drama anthology Viva Spotlight by Armando “Bing” Lao, Jeturian’s primary screenwriter-collaborator.32 Jeturian describes the narrative kernel of Pila Balde as a “simple story about a young couple who dreamt of having a better life but the environment made it difficult for them.” According to Jeturian, the director of the original television episode, Joel Lamangan, felt that “there seems to be nothing much happening with the story, because it’s not story-oriented. The plot was so simple.” For Jeturian, however, the simplicity of the social realist narrative enabled a focus on “the culture, the environment” surrounding the struggling protagonists. However, he faced the difficulty of pitching this spare social realist narrative to a mainstream production studio, Regal Films. Joey Gosiengfiao, the supervising producer of Regal’s pito-pito division, Good Harvest, gave the green light for the film on one condition: he asked Jeturian to “put in a lot of sex.” The studio’s demand to transform a social realist narrative into a commercially viable sex film is parodied in Jeturian’s next film, Tuhog, released in 2001, two years after Pila Balde. The filmmaker relates: “Tuhog was a satire on sex in Philippine cinema. The first scene of Tuhog is this director proposing material to a producer which he read from a tabloid about a rape-incest victim. And the producer said ‘o sige’ [okay], he gave the green light for the project, but he said, ‘basta gawin mong sexy’ [just make it sexy].”33

Jeturian’s acquiescence to the studio requirement to retool Pila Balde as a sexploitation flick can be traced to his view of genre filmmaking as a vehicle for social realism: “I want to tackle real stories. It’s just my way of telling them that varies. Like, I can use a sex comedy. I use different genres to show real stories.”34 It was also partially motivated by Jeturian’s desire to prove his mettle as a commercially viable film director following the commercial failure of his first film, Sana Pag-Ibig Na, which had won critical praise but had failed to attract popular audiences the year before: “My first film was a very wholesome family drama but it bombed at the box office. But it got awards and it won for the actress a Best Actress award. So in my second film, I was ready to inject some sex into it just to be able to prove to my producer that I can be a mainstream director. And also because I thought the material could stand some sex. That was the only way I could convince my producer to allow me to do a socially relevant subject.”35 Upon rescreening Pila Balde with a Munich film festival audience in 2004, Jeturian felt in retrospect that “there was too much sex in the movie … it could have stood some editing. I felt guilty for succumbing to the requirements of the producer to put in a lot of sex.” The proliferation of sexploitation films under a liberal Board of Censors chief had created a climate in which a director’s addition of extraneous sex scenes became necessary “to compete, to get approval from the producer.”36

Gratuitous sex notwithstanding, Pila Balde’s naughty humor and its libertarian, “non-pontificating” framing of socially relevant material resonated favorably with popular audiences and film critics alike.37 The film’s success at crafting a dual-tiered mode of address to both moviegoers with a preference for commercial fare as well as film reviewers drawn to adept filmmaking and social insight is signaled by the canny double entendre of the film’s title. Jeturian explains:

The original title, Pila-balde, means lining up for water but it has a sexual connotation to it. It means gang bang, a girl with guys lining up to have sex with her… . It’s for the audience who loves to watch sex films, that’s why it has a naughty title. But at the same, I was hoping that even if they are there for the sex, they’d realize it’s not just an ordinary sex film. If I consistently do films of this sort, then probably I would create an audience for my movies, more than just having viewers who are after sex. My target is also people who go for good cinema. Because my first film got good reviews and my second film got good reviews, I’d like to think I’m succeeding in creating an audience for my films.38

As Jeturian’s comments make clear, the film’s title had a risqué connotation in urban slang, and served to signal the film’s explicit sexual content to local audiences. Underscoring the prurient connotation of the movie title, the first close shots of the communal faucet around which young men use a hand pump to collect water from a deep well (poso) are accompanied by the offscreen sound of street boys joking about getting an erection. By blatantly inviting a phallic reading of the hand-pumped faucet, the act of fetching water is overtly sexualized from the beginning of the film (Figure 14.1).

Figure 14.1 In Pila Balde [Fetch a Pail of Water, dir. Jeffrey Jeturian, 1999], both the film’s title and early expository scenes overtly sexualize the act of fetching water from a communal water pump.

Shot on location in Quezon City, Pila Balde explores the intersecting lives of two neighboring communities entangled in what Jeturian calls an “economic circle”: the lower-middle-class residents who live in the Marcos era tenements built in the late 1970s by the Bagong Lipunan Sites and Services (BLISS) and the urban poor squatters who live in the adjacent slum area, known as manggahan (mango groves; ironically, the area appears treeless).39 By the end of the 1970s, First Lady Imelda Marcos had amassed an enormous degree of power: she held the offices of assemblywoman, minister of Human Settlements, and governor of Metro Manila. Imelda Marcos famously christened the national capital region of Metro Manila the “City of Man,” aiming to achieve “low-cost housing for the poor,” the “upgrading of blighted areas,” and the overall “beautification” of the city.40 The government’s BLISS housing projects established condominiums in “the most depressed areas within each region, province, town, or city” and promised to provide basic needs—water and power foremost among them—to the nation’s poorest citizens.41 Two decades later, Jeturian’s location filming for Pila Balde in the low-income housing projects of Quezon City exposes the false claims of the Marcos period. The title makes literal reference to the failure of government-owned utilities to pipe water into all corners of the city, and the chronic lack of water and electrical power looms large in the lives of the film’s protagonists. (Offscreen, periodic water shortages in Metro Manila persist to the present day.42) In this film about spatial proximity between people of distinct socioeconomic strata, the scarcity of water functions as a potent leveler between classes because neither the middle-class residents nor their poor neighbors have access to water indoors. Everyone is forced to fetch water at a communal outdoor faucet, though the comparatively wealthier tenement residents pay the young men of the slums to do it for them. In one scene, a water carrier offers his services as an in-home masseuse to a university professor, bearing out the link between water and sex established in the film’s opening scenes.

Pila Balde is ostensibly a narrative about how Gina (Ana Capri), a slum girl who dreams of being rescued from poverty by her better-off neighbor, Jimboy (Harold Pineda), becomes bitterly disillusioned when he tosses her aside as a mere sexual conquest. The film, however, is much more than the story of how Gina learns to entrust her heart to Nonoy (Marcus Madrigal), a truer though poorer lover, and with him to try to eke out a life in the midst of poverty, sexual and economic exploitation, and the death of loved ones (Figure 14.4). As Jeturian recognized, the narrative progression of events in Gina and Nonoy’s lives is not the sole focus of spectatorial engagement. Instead, the viewer follows the densely crisscrossing paths of multiple characters in a milieu film crammed full of several other interesting figures: the usurer Mrs. Alano (Becky Misa), who aggrandizes herself at the expense of others and routinely shortchanges the slum workers for their labor; Lola Cion (Estrella Kuenzler), Gina’s loving but gambling-addicted grandmother; the loudmouthed Shirley (Amaya Meynard), who works at a sex club; and Mr. Ocampo (Edwin Amado), the gay male professor who cruises the young men of the slums as they haul water for their wealthier neighbors. The real reason that Pila Balde draws us in is its capacity to sketch vibrant characters and the texture of everyday life in the context of interclass dynamics of desire, exploitation, dependency, and distrust.

The film takes up the question of what happens when two proximate but distinct socioeconomic classes live at close quarters with one another. As a result, setting is the most conspicuous formal element in the film, a clear visual analogue for the narration’s spatialization of class relations. Pila Balde portrays class antagonisms as a set of entanglements between neighbors. Class dynamics are visualized through both spatial proximity and spatial distinction: though the middle-class apartment building and the slums are right next to one another, the tenements appear to tower over the shanties below. The beginning of the film introduces this spatialization of class through two complementary establishing shots, each taken from the perspectives of the different classes: a high-angle shot from an upper floor stairwell of the middle-class housing complex overlooking the rooftops of the slum dwellings (Figure 14.2) is followed directly by a low-angle shot from street level in an alleyway of the slum community, showing the middle-class tenement housing overshadowing the homes of the urban poor (Figure 14.3). The implication is clear: these two class-stratified spaces may be adjacent, but they are not equal.

Figures 14.2 and 14.3 The spatialization of class in Pila Balde is introduced through two complimentary establishing shots: a high angle shot from the perspective of the middle-class apartment building overlooking the slums, followed by a low-angle shot from the perspective of a slum alley in which the tenement building towers over the homes of the poor.

The film explores relations of antagonism as well as intimacy, exploitation, dependency, and duplicity between classes. Though neither class is innocent—the squatters occasionally cheat their wealthier neighbors at gambling and illicitly tap their electrical lines for power—the film is staunchly on the side of the underclasses for the greater sins of exploitation perpetrated by the rich on the poor. The middle-class residents exploit the slum dwellers’ poverty (Mrs. Alano’s usury), their sexual vulnerability (Jimboy’s duplicitous seduction of Gina), and the larger precariousness of their social situation (once the slums are razed in the squatter fire that ends the film, the poor face the possibility that the government will forcibly relocate them to areas far from their sources of work).

Jeturian has remarked that he endeavors to create films that allow “people to see how lucky they are and how unlucky some people can be also,” striving to “erase the barriers of discrimination and prejudice” between classes. Pila Balde’s exploration of class discrimination is evident in two parallel conversations where confidences are exchanged between members of the same class: Mrs. Alano complains to Professor Ocampo that the tenement environment was much less seedy before squatters moved into the adjacent land. The professor’s response, however, indexes what Mrs. Alano has disavowed: the middle-class residents’ dependency on their social and economic subordinates for cheap domestic and sexual labor, from housemaids and laundrywomen to water carriers and masseuses. In a later sequence in the film, Gina tells her imprisoned father how she was able to the raise money for her grandmother’s funeral: through a combination of abuloy (donations to the grieving family) and sugal (gambling). Gina relates that her friends from the slums cheated at mahjong and donated their winnings to the family’s meager funds for the funeral. Gina’s account prompts her father to laughingly remark that their tenement neighbors are dupes. Thus, a variant of class racism is conspicuously paralleled in both conversations: the rich, say the poor, are easily deceived, whereas the poor, say the rich, are thieves.

Figure 14.4 Sweethearts Nonoy (left) and Gina (right) are the enterprising albeit impoverished protagonists of Pila Balde.

Jeturian has called attention to the prior scene in interviews, saying that Mrs. Alano’s discrimination against the poor “is ironic because the lady who lives in the tenement housing isn’t really that rich except that she’s probably a notch higher than the poor folks but that somehow gives her license to oppress those under her.” Mrs. Alano becomes, for Jeturian, emblematic of the film’s critique of materialism and class prejudice, of the overvaluation of money in the context of pervasive poverty.43 Jeturian’s film also links economic impoverishment to a street-level, lower-income form of entrepreneurialism: “If you noticed, the main characters, even if they are young, know how to make ends meet. They know how to make a living just by fetching water, by driving a tricycle or even prostituting themselves. That goes for most Filipinos.”44

Gina and Nonoy, the entrepreneurial protagonists of Pila Balde, are both enterprising young people who hold down several simultaneous jobs to support dependent adults (Gina’s ailing grandmother and Nonoy’s alcoholic father are both infantilized by their gambling addictions and no longer able to provide for the family). Gina sells snacks and does paid housework and laundry; Nonoy drives a tricycle, delivers water to middle-class residents, and prostitutes others and himself in an underground economy for gay as well as straight sex.

The internalization of an entrepreneurial mentality is, for Brown, a key feature of neoliberal governmentality. The citizen-subject normatively constructed by neoliberal governmentality is a homo oeconomicus,45 behaving calculatively towards his or her life and that of others, an entrepreneur who, in the context of the minimal state’s abdication of its old role as provider of social protections, is charged with “self-care,” or the responsibility of looking out for oneself. Brown elaborates:

In making the individual fully responsible for her/himself, neoliberalism equates moral responsibility with rational action; it relieves the discrepancy between economic and moral behavior by configuring morality entirely as a matter of rational deliberation about costs, benefits, and consequences. In so doing, it also carries responsibility for the self to new heights: the rationally calculating individual bears full responsibility for the consequences of his or her action no matter how severe the constraints on this action, e.g., lack of skills, education, and childcare in a period of high unemployment and limited welfare benefits.46

In Pila Balde, neoliberal rationality reverberates in the actions of the impoverished-and-hence-entrepreneurial protagonists. As the state reneges on its responsibility to offer social protections to the least of its citizens, makaraos (to survive, to carry on) and makaahon (to move up the socioeconomic ladder) become commonplace expressions for the need to look out for oneself and, if possible, rescue oneself from poverty by any means possible. The neoliberal entrepreneurial subject so formed is active in self-interest and self-aspiration but politically nihilistic and passive because agency is never construed in collective terms: “the model neo-liberal citizen is one who strategizes for her/ himself among various social, political and economic options, not one who strives with others to alter or organize these options.”47 In the context of the state’s abdication of its basic obligations to its citizens, Filipinos citizens are hailed as self-rescuing neoliberal subjects, prompted to adopt an entrepreneurial, politically nihilistic perspective on themselves and their own lives in the context of widespread poverty. Yet alongside Pila Balde’s acute portrait of the atomizing neoliberal citizen as self-oriented entrepreneur is an equally potent ethos of neighborly, collective assistance. This communitarian ethos is explicitly linked to gambling and death in the conversation between Gina and her imprisoned father about the slum dwellers who donated their gains at gambling to Lola Cion’s funeral funds. In that conversation, Gina recounts how the family was able to pay for the high costs of death—kabaong, lote at nicho (a coffin and burial niche)—through both abuloy (donations from neighbors and acquaintances) and tong sa sugal (the proceeds from public gambling at the wake, where Nonoy and his friends duped the tenement residents in order to raise money for the funeral). Gina’s father responds incredulously to this mixture of duplicity and generosity: “May tarantado palang mabait, ano?” (So, even tough guys can be kind?) In hindsight, such scenes in Pila Balde can be seen as foreshadowing the links between gambling, death, and communitarian assistance pursued by the film Kubrador, released seven years later.

The Dangerous Life of A Kubrador [Bet Collector]48

Several aspects of Kubrador’s prologue highlight the deep ties between the gambling underworld and the corrupt national government. The opening intertitles point to jueteng payolas as being linked to both deposed leader Joseph “Erap” Estrada and family members of former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, whose husband, First Gentleman Mike Arroyo, was also accused of involvement in jueteng.49

If Pila Balde was characterized by the prominence of setting—the proximity of middle-class tenement housing to the manggahan slums—then Kubrador is distinguished by the revelation of space through camera movement. The film is seen through the lens of a mobile handheld camera that is by turns invasive or unobtrusive. A probing, jerky camera follows the movements of characters through long, revelatory takes. The film’s most prominent motifs of cinematography and editing—handheld following shots in combination with long takes—are first introduced in the film’s prologue, when the camera follows Toti, a kubrador or bet collector on his way to a bolahan or drawing of winning jueteng numbers. Toti’s T-shirt, prominent as he makes his way along the winding alleys of the slums, is emblazoned with the face of matinee idol and former presidential aspirant Fernando Poe Jr., popularly nicknamed “FPJ.” The injunction on the front of Toti’s shirt, ituloy ang laban (on with the fight), alludes to the 2004 presidential race in which FPJ is widely believed to have won more votes than Arroyo, (Figures 14.5 and 14.6), though Arroyo was declared victorious

Figure 14.5 Allusions to electoral fraud in Kubrador [The Bet Collector, dir. Jeffrey Jeturian, 2006]: The back of a bet collector’s shirt bears the face of matinee idol and former presidential aspirant Fernando Poe Jr.

Figure 14.6 In Kubrador, the exhortation on the front of a bet collector’s shirt, “ituloy ang laban” (“on with the fight”) alludes to electoral fraud in the last presidential race of 2004, when Gloria Macapagal Arroyo was declared victorious.

When Toti rests his bet-book on the table, a close shot of the tabloid headline underneath refers to the failed attempt to impeach President Arroyo despite proof of her direct involvement with large-scale vote tampering (Figure 14.7). The association between fraudulent elections and jueteng is obvious to local spectators well aware that campaign funds and political war chests are augmented by gambling payolas.50

Figure 14.7 The tabloid headline below a jueteng bet-book in Kubrador refers to the failed attempt to impeach President Arroyo for vote tampering in the 2004 presidential elections.

Moments later, the jueteng proceedings attended by Toti are interrupted by a police raid, and a memorable chase scene ensues in which the police pursue Toti across the rusty metal rooftops of the slums. This energetic expository sequence introduces the viewer to the dangerous life of a jueteng bet collector while also embedding its story of an individual kubrador in the larger, politically charged context of corruption under two presidential administrations.

After Toti’s arrest, the handheld camera turns its attention to the film’s real protagonist, Amy (Gina Pareño), a middle-aged kubrador trudging through the intricate, claustrophobic maze of slum dwellings in Barangay Botocan, Diliman.51 The hazardous daily existence of a jueteng bet collector is brought home in the very first line of dialogue Amy utters in the film. Starting her workday with a prayer, Amy entreats: “Sana po, hindi po ako mahuli ngayon” (Lord, grant that I don’t get caught today).

More than the ever-present threat of police raids on low-ranking jueteng workers, the film drives home the notion of a state steeped in corruption and hypocrisy. On the street level, the very policemen who arrest Amy instruct her to take down their bets on the sly. The chief of police (Soliman Cruz), who places a “secret bet” with Amy, sits at a large desk behind which Arroyo’s portrait is prominently displayed, a visual reminder that the state, in refusing to legalize jueteng, institutionalizes a form of corruption that permeates the government from top to bottom (Figure 14.8).

Figure 14.8 When Amy is arrested for collecting illegal gambling bets in Kubrador, the head of the precinct places his own “secret bet” with her. A portrait of President Arroyo is prominent behind the police chief’s desk.

When Mang Poldo (Johnny Manahan), a prosperous-looking jueteng “cashier,” prepares envelopes containing large payoffs to various congressmen, he ruefully reminds his underlings that the jueteng world finds “crocodile” politicians useful (“may pakinabang sa buwaya”). Scenes at Mang Poldo’s mansion show piles of Philippine currency—jueteng bet collections ranging from small change to larger bills—being hastily shoveled into large bags. Referring to this scene, the director notes, “The poor man’s money gives these powerful people the food on their table, without the poor knowing it.”52

Amy, the street-level kubrador whose labor helps to feather the nests of big jueteng operators, collects kubra or bets to augment her family’s meager income. A chain-smoking middle-aged woman with a tough-asnails temperament, Amy is also compassionate and personable. As realized by veteran actress Gina Pareño’s superbly nuanced performance,53 Amy emerges as a well-liked figure in the close-knit slum community: she sends off a goddaughter with good-natured warnings to her new American husband to behave himself, and is a reliable neighbor regularly called upon by the parish priest to collect funeral donations for grieving families. In spite of her solid standing in the community, Amy is deep in debt to her jueteng manager, constantly borrowing against her future earnings (bale) by guaranteeing these pay advances with expected remittances from a daughter working overseas. Amy takes a 15 percent commission from each small bet, which results in a scant daily wage (in one scene, her commission from a day’s jueteng collection amounts to less than two U.S. dollars).

Amy’s story unfolds over a three-day period, during which we watch her ply her trade, a disarming kubrador who is equal parts bet collector, confidante, and friend. Some of Amy’s clients bet on the birth date of someone they love, converting what is dearest in their lives into a value they can gamble on. Whenever a cash-strapped potential bettor cites a recent tragedy to explain their inability to place a bet, Amy translates such experiences of misfortune into numbers that can be played for money: a tricycle accident is otso trese (eight for the motorcycle wheels, thirteen for the passenger sidecar); children caught stealing from school translates as bente at singko (five stands for child, twenty for thief).54 Amy even translates as trese bente nwebe (thirteen, crying, twenty-nine, death) her own empathetic grief for Tatang Nick (Domingo Landicho), whose loss of a beloved grandchild reminds her of the death of her own son Eric (Ran del Rosario). To all these life tragedies, to sufferings great and small, Amy assigns a number for which she or others stake a bit of cash: the conversion of everyday experience into a profit-making activity means that, in placing a bet derived from her own grief, Amy earns a percentage from her own sense of loss. This is neoliberal reification lived on the ground, in the lives of the very poor, a suffusive, hardscrabble, entrepreneurial translation of everything— from anecdotes related in casual social interactions to the deepest pains of the heart—into a numerical value from which to calculate a profit.

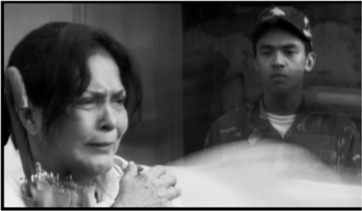

Amy’s dead son, Eric, who had been employed as a soldier for the Philippine Armed Forces, appears at four key moments in the plot’s three-day arc. A spectral figure in a military uniform, Eric looks on kindly from the doorway behind his harassed mother as she makes a phone call on the morning of the first day. Later that evening, when Amy comes home exhausted from her ordeal at the police station, the ghost of her son caresses her feverish forehead as she sleeps. On the afternoon of the second day, Amy loses her way in the dense alleys of an unfamiliar shantytown and is on the verge of panic when the ghost of her son, calmly passing unseen behind her, shows the way home. On the third and last day of the plot, Amy is visiting her son’s gravesite at Manila’s overcrowded North Cemetery to commemorate Araw ng Patay (All Saint’s Day, November 1), when she witnesses an accident between a public transport jeepney and a privately owned car. The enraged motorist fires a gun at the jeepney driver but misses, seriously injuring a passerby. Amy is watching the injured man being rushed to the hospital when it dawns on her that she too is bleeding from her left shoulder. As Amy pauses, stunned and distraught, her dead son looks on unseen behind her. In contrast to other people hastily making their way through the cemetery, the wounded mother and her spectral son are isolated by their stillness and silence against the speed and uproar of the city crowd (Figure 14.9). The last shots are of the gunman being mauled by an indignant mob and subsequently rescued by the police. Kubrador’s penultimate scene thus drives home what we know to have been true all along: Amy’s precarious life is constantly grazed by death.

Figure 14.9 In Kubrador’s penultimate scene, Amy’s shoulder is grazed by a gunshot as the spectral figure of her son looks on, unseen, behind her. Amy and her son are isolated by their stillness amid the speed and uproar of the overcrowded city cemetery on All Saint’s Day.

For Jeturian, the ghost motif in Kubrador explains Amy’s refusal to give up in the face of poverty, illness, and soaring debt: “the memory of her son and her love for the family keeps her going throughout her daily routine, to go on living.” Perhaps more importantly, the spectral resolution reveals the filmmaker’s interest in illuminating the inextricability of life and death in the story world.55

Gambling on Life and Death: From Kubra to Abuloy

Even more than in Pila Balde, debt and gambling structure both life and death in Kubrador’s story world: the poor are overrun by usurious debts (five-six refers to the 20 percent monthly interest rate charged by local loan sharks); Amy’s underemployed husband obsessively watches luck-based game shows on TV; and death becomes a matter of money because funeral expenses pose a heavy burden on the poor. To help Tatang Nick raise money for his grandson’s burial, Amy and other neighbors set up gambling tables for dama (checkers), mahjong, and the card game tong its for the wake. Amy’s workday routine blurs the distinction between collecting a funeral donation (abuloy) and soliciting money for a bet (kubra). This point is made with understated humor early in the film: when a policeman tries to arrest Amy, she attempts to disguise the true nature of her bet-book by claiming that it is merely a list of funeral donations: “Sir, abuloy lang yan.” Personally requested by the parish priest to collect funds for a bereaved family, Amy carries out her neighborly duty with conviction, managing to convince even a skeptical rice vendor that sympathy for the dead and the bereaved should not be limited only to personal acquaintances and friends. When she approaches Mang Poldo for a sizable abuloy, he sums up her character perfectly: “dalawa lang naman ang pinagkakaabalahan mo: jueteng at patay” (You’re only ever interested in two things: jueteng and the dead).

The literal and figurative links between placing a jueteng bet (kubra) and giving a donation for the family of the deceased (abuloy) in Kubrador are glossed by Jeturian as follows:

Amy’s character represents also a position of trust; in the community that she belongs to, people trust her. That’s why she’s given the responsibility to collect abuloy. And there’s a possible parallelism there: the money that she collects also as jueteng collector is probably an abuloy also, isn’t it? … She gets to collect abuloy while she collects money also as bets. But this can probably be the same donation, for these people, who aren’t aware of it, sort of symbolically an abuloy for their own death also. These are living deaths also, the kinds of lives that they lead.56

For Jeturian, the figurative continuum between placing a bet and giving donations for the bereaved hinges on the notion of suerte (luck), the hope that a windfall from gambling might provide an escape route from an impoverished death-in-life. In a diegesis where slum dwellers have very few opportunities for social or financial advancement, a bet, no matter how poor the odds, can hold out the promise of a better future. As mentioned earlier in this chapter, the notion of betting on oneself extends extra-cinematically to the conditions of 1990s pito-pito filmmaking, when fledgling filmmaker-entrepreneurs were forced to acquiesce to the structure of the abono. A director who advances personal funds to complete a film does so with the explicit understanding that the abono is a personal investment, a form of betting on oneself and one’s future in filmmaking.

To a large extent, the down-market entrepreneurialism of Amy and other bet collectors in Kubrador can be seen to affirm the neoliberal rationality of homo oeconomicus. That the protagonists of Kubrador and Pila Balde are driven, but not despairing, calls to mind a point made by Wendy Brown in a recent interview. “I am not convinced,” Brown remarked, “that neoliberalism produces despair.” Rather, it produces a nihilistic, everyday form of pragmatism. She elaborates:

neoliberalization actually seizes on something that is just a little to one side of despair that I might call something like a quotidian nihilism. By quotidian, I mean it is a nihilism that is not lived as despair; it is a nihilism that is not lived as an occasion for deep anxiety or misery about the vanishing of meaning from the human world. Instead, what neoliberalism is able to seize upon is the extent to which human beings experience a kind of directionlessness and pointlessness to life that neoliberalism in an odd way provides. It tells you what you should do: you should understand yourself as a speck of human capital, which needs to appreciate its own value by making proper choices and investing in proper things. Those things can range from choice of a mate, to choice of an educational institution, to choice of a job, to choice of actual monetary investments—but neoliberalism without providing meaning provides direction.57

Neoliberalism, for Brown, supplies direction but not meaning: we learn to view ourselves through entrepreneurial eyes, using our decisions to “invest” in ourselves and others. Yet unmistakably, one glimpses in both Pila Balde and Kubrador, despite and alongside this interiorization of entrepreneurship as a generalized code of conduct, a communitarian sense of reciprocity, one that tempers individualistic neoliberal directives, in the practice of abuloy. Outside the story world, abuloy also recalls the remittances of overseas Filipino workers on which not only family members but the Philippine economy itself are crucially dependent.58 Abuloy as ethic of care fails to constitute radical organized collective action; nonetheless, it does confer meaning through other-oriented acts and softens what Brown calls “the ghastliness of life exhaustively ordered by the market and measured by market values.”59 The continuum between kubra (a bet placed for oneself) and abuloy (a contribution for another) depends on the reciprocal faith that others will do the same for you should the need arise.

If the neoliberal ideal is one in which “men and women follow unimpeded self-interest in the marketplace” then this unrestrained self-interest in the context of scarce resources, oblivious to “economic immiseration, exploitation, and inequality”60 is not what we see in Kubrador. The enterprising and nearly destitute Amy works to keep herself alive, but more importantly, she works in order to sustain others: primarily her family, but also her neighbors, those who have died in her life and in theirs, and those survivors, herself among them, that mourn them in a kind of death-in-life.

The protagonists of Kubrador and Pila Balde face their grim circumstances with a casual, streetwise levity, a lightly ironic willingness to eke out a living under the most impoverished conditions. Jeturian’s films betray what might be called a neorealist sense of humor (he has indicated his preference for “neorealist” style in combination with what he calls a “casual,” “accessible” tone),61 a grim levity that, peppered across the harshness of his protagonists’ circumstances, leaves film critics somewhat divided. Whereas some foreign reviewers complain about the hopelessness of Jeturian’s harsh story worlds, several local critics have responded warmly to the role of humor in his films. A writer for Visual Anthropology complains that Kubrador “falls short on human action and any ability to produce change,” resulting in a film steeped in despair: “there is nothing redeeming about the filmed situation—only dire circumstances that kill hope, and indications that Amelita, her family and her community will remain forever entrenched in their current existence.”62 In contrast, an appreciative review for the Philippine news daily Business World highlights the film’s communitarian ethos (“there is so much humanity in this community of illegal gamblers”) and notes that “humor is injected and effortlessly executed” to “lighten the heaviness of the topic.”63 The affective resonances emphasized in these reviews are diametrically opposed: where one critic sees atomizing despair and passivity, another detects communal lightheartedness.

On the one hand, this levity and good humor could be the fatalistic mask of neoliberal passivity, what Pierre Bourdieu calls a “screen discourse” of accommodation that accepts cultural, economic, and political domination because they are seen as inevitable.64 On the other hand, both Pila Balde and Kubrador arguably nuance the screen discourse of accommodation by unmasking neoliberalism’s “debased appeal to pragmatism” as always prior to social justice, and by powerfully contesting what Henry Giroux calls “the central neoliberal tenet: that all problems are private rather than social in nature.”65 The tonal complexity of Jeturian’s films is rooted in their depiction of a calculative entrepreneurial subjectivity modulated by something it has not fully subsumed: an ethos of communitarian reciprocity that sustains the diegetic protagonists in life as well as in death.

Acknowledgments

This chapter is for Joya Escobar, in whose company I first screened Kubrador at the Cinemalaya festival in 2006. My thanks also to Jeffrey Jeturian, who graciously agreed to be interviewed for this study and who generously provided a commercially unavailable English-subtitled DVD of Kubrador for my students in Philippine Cinema at the University of California, Irvine.

Notes

1 Yvonne Ng, 2001, par. 19.

2 Jeffrey Jeturian, interview with author, July 27, 2009.

3 For Wendy Brown, the Foucauldian concept of ‘governmentality’ designates what Foucault called “the conduct of conduct.” The question of interiorized “mentality” emphasizes subject formation rather than state control or coercion. Brown, 2003.

4 Ibid., par. 2 and 6.

5 With regards to Brown’s notion of neoliberalism as the extension of market rationality beyond the market, she contends that “neoliberalism entails the erosion of oppositional political, moral, or subjective claims located outside capitalist rationality but inside liberal democratic society, that is, the erosion of institutions, venues, and values organized by non-market rationalities in democracies. When democratic principles of governance, civil codes, and even religious morality are submitted to economic calculation, when no value or good stands outside of this calculus, sources of opposition to, and mere modulation of, capitalist rationality disappear” (2003, par. 20). Brown notes that despite the Left’s skepticism and ambivalence toward liberal democracy, the latter did stand as an important mode of “modulating” and “tempering” capitalist rationality even as it often worked as a ruse or justification for capitalist stratification. “Liberal democracy cannot be submitted to neo-liberal political governmentality and survive. There is nothing in liberal democracy’s basic institutions or values—from free elections, representative democracy, and individual liberties equally distributed, to modest power-sharing or even more substantive political participation—that inherently meets the test of serving economic competitiveness or inherently withstands a cost-benefit analysis.” Neoliberal rationality saps civic values that are not derived from a profit orientation of their strength, substituting principle with pragmatism: “one of the more dangerous features of neo-liberal evisceration of a non-market morality lies in undercutting the basis for judging government actions by criteria other than expedience” (ibid., par. 21, 23, and 27).

6 Ibid., par. 9 and par. 21.

7 Ibid., par. 38.

8 The Asian economic collapse of 1997 had devastating effects on the Philippines, though the Philippines was not itself perceived as having reached the status of a “Tiger” economy, as Newsweek noted in 1996: “the Philippines has begun to emerge from nearly a century of dependence on the United States and is ready, at last, to join the ranks of Asia’s economic ‘tigers’” (Elliot 1996).

9 Bliss Cua Lim, 2000, par. 3. In 2009, the amusement tax was lowered from 30 percent to 10 percent, but domestically produced films in the Philippines still face a bevy of other taxes: withholding tax (5 percent), value-added tax on the producer’s earnings (12 percent), and a corporate income tax (35 percent). Onerous taxation is seen as contributing to the decline of Filipino movie production, from 250 movies annually to less than fifty-three movies annually since 1996. See Crispina Martinez-Belen, 2009. See also Lira Dalangin-Fernandez, 2009. http://showbizandstyle.inquirer.net/breaking-news/breakingnews/view/20090316-194479/Arroyo-urged-Enact-loweramusement-tax-law

10 Annalisa Vicente Enrile, 2009, p. 66.

11 Jeturian remarks: “That was one of my quarrels generally with Filipino films. Because for us, for something to be dramatic, somebody has to be raped, kidnapped or have an extramarital affair. So we’re not used to simple stories which at the same time have this ability to move you, to touch you. So we went through [screenwriter Armando “Bing” Lao’s] files and I said, ‘here Bing, this might be good.’ I don’t remember if Pila Balde was the original title. But the problem was it was a social realism story, it was a simple social realism story, so we wondered, ‘how will we do this when our studio is Regal Films, such a mainstream studio?’” Jeturian, interview with author. The interview was conducted in a mixture of Tagalog and English; all translations from Tagalog in this chapter are my own.

12 Ng, 2001, par. 6.

13 Though the term abuloy can refer broadly to the act of contributing to a person or to a cause, in Jeturian’s films, abuloy primarily refers to donations to assist the bereaved in defraying expenses incurred by the death of loved ones.

14 Henry Giroux writes: “Neoliberal global policies have been used to pursue rapacious free-trade agreements and expand Western financial and commercial interests through the heavy-handed policies of the World Bank, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in order to manage and transfer resources and wealth from the poor and less developed nations to the richest and most powerful nation-states and to the wealthy corporate defenders of capitalism” (2005, p. 6).

15 See Jamie Morgan’s (2003, pp. 545–546) succinct and insightful account of the neoliberal underpinnings of the 1997 Asian economic crisis.

16 For contemporaneous accounts of the attacks on Southeast Asian currencies by speculators that exacerbated the Asian economic crisis, see Eugene Linden, 1997, pp. 26–27; Sonny Melencio, 1997.

17 Lim, 2000, par. 4. See also Roger Garcia, 2000, pp. 53–55.

18 Ng, 2001, par. 8.

19 Garcia, 2000, pp. 53–55.

20 Jeturian, interview with author. Of the shooting ratio in contemporary Hollywood productions (the ratio of exposed footage to the actual shots included in the finished film), David Bordwell explains: “For every shot called for in the script or storyboard, the director usually makes several takes … Not all takes are printed, and only one of those becomes the shot included in the finished film … A 100-minute feature, which amounts to about 9,000 feet of 35 mm film, may have been carved out of 500,000 feet of film.” Bordwell’s example would yield a very high shooting ratio of about one to fifty-five. See David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson, 2008, pp. 20 –21.

21 Ng, 2001, par. 8. The fiery climax of Pila Balde also recalls the squatter fire portrayed in Lino Brocka’s Maynila: Sa Kuko Ng Liwanag (Manila: In the Claws of Neon, 1975), a social realist film on rural–urban migration and poverty that ushered in the Philippine New Cinema of the 1970s. In Brocka’s Maynila, the fire that razes the slums served to foreclose the budding romance between two poor but virtuous characters, whereas in Pila Balde, the squatter fire that takes Nonoy’s father’s life brings him closer to Gina, who is still in mourning for her late grandmother. As explored later in this chapter, the thematic of loving supportiveness in the context of death-inlife is prominent in both Pila Balde and Kubrador.

22 Jeturian notes that today, in the context of a declining Filipino film industry, ABS-CBN’s film division Star Cinema has become more active than Regal Films in terms of 35 mm theatrical film output. Jeturian, interview with author.

23 Lim, 1998, par. 7–11.

24 Garcia, 2002, pp. 53–55. Noel Vera also credits a film festival of Good Harvest productions in 1998, which showcased the pito-pito work of new directors like Lav Diaz and Jeturian, with fueling a “mini-renaissance” of Filipino filmmaking. See Noel Vera, 1999, p. 30.

25 Garcia writes, “it is Lavrente (Lav) Diaz, with three Good Harvest features and a string of international festival credits, who has emerged as the major writer-director talent of this group” (2002 , p. 55). Diaz’s first film, Serafin Geronimo: Ang kriminal ng Baryo Concepcion (Serafin Geronimo: The Criminal of Barrio Concepcion, 1998), was a Good Harvest production.

26 Lim, 2000, par. 12.

27 Jeturian, interview with author.

28 The quote continues: “His specific situation is defined by the fact that his labour-power is his only possession. His fate is typical of society as a whole in that this self-objectification, this transformation of a human function into a commodity reveals in all its starkness the dehumanized and dehumanizing function of the commodity relation” (1968, p. 92).

29 Ibid., p. 100.

30 Iskho F. Lopez, 1999, p. 24.

31 Pila Balde won the Gold Award at the 2000 Worldfest International Film Festival in Houston; the NESPAC Jury Prize in the First Cinemanila International Film Festival in 1999; and three Gawad Urian Awards from the Manunuring Pelikulang Pilipino (Philippine Film Critics Circle) for Best Screenplay, Best Editing, and Best Production Design.

32 Armando “Bing” Lao is credited for story and screenplay for the first three films directed by Jeturian: Sana Pag-Ibig Na (1998), Pila Balde (1999), and Tuhog (2001). Lao is also credited with screenplay supervision for two of Jeturian’s more recent films: Bridal Shower (2004, story by Chris Martinez) and Kubrador (2006, story by Ralston Jover, whom Jeturian describes as a student of Lao’s).

33 Jeturian, interview with author. Jeturian also described the parodic content of Tuhog in similar terms during his 2001 interview with Ng: “[Tuhog/ Larger than Life is] also a parody of Philippine cinema, the way we do films, the way we hype everything just to make it ‘cinematic.’ It’s also a dig at our tendency to make our films look like Hollywood. It was written by the same writer who did Fetch a Pail of Water. In the very first sequence, there’s this film director who’s proposing the film material and the producer approves it but gives instructions to the director to make the film very sexy—the same thing that happened to me. And that gives him license to distort the story” (Ng 2001, par. 18).

34 Jeturian, interview with author.

35 Ng, 2001, par. 9.

36 Jeturian, interview with author. Local and foreign critics remarked on the presence of gratuitous sex in Pila Balde: Variety’s otherwise favorable review noted that “several nude scenes … pepper the pic and look like commercially motivated inserts.” Filipino critic Noel Vera’s largely glowing review of Pila Balde likewise observes: “The sex scenes tend to stick out, which bothered some people who’ve seen the film … you can’t help but think that the sex in Pila Balde is there not because it needs to be there but because it helps sell the picture.” See Elley, 2000; Vera, 1999, p. 30.

37 Vera’s review of Pila Balde commends Lao’s screenplay for “a superbly realized context—that of a community of upper-lower to lower-middle class families, living in close, rubbed-shoulders proximity with each other. [Lao] throws in a few sharp social observations—one middle-class character notes that the nearby squatters provide a source of cheap and ready labor—but does so lightly, without unnecessarily heavy pontificating or preaching” (1999, p. 30).

38 Ng, 2001, par. 3 and 13.

39 Jeturian has commented that “BLISS represents the thrust of the Marcos government, it represented the dream of every Filipino … housing for the poor. [This allusion to the Marcos government] probably wasn’t intentional in the film. But at the same time, now that you mention it, it did represent every man’s dream to have decent housing.” Jeturian also recalls that he chose the location for Pila Balde based on “the proximity of BLISS with the slums. If you did it in a village residence it’s like you would just be talking about an individual family, an individual entity. Whereas in BLISS, it represents an economic circle where those who are in the circle a bit above others [medyo nakakaangat] don’t want to be classified with those below them.” Jeturian, interview with author.

40 See contemporary coverage of BLISS and other Ministry of Human Settlements projects in Focus Philippines, a Marcos-controlled periodical. Wilfrido D. Nolledo, 1979, p. 24 –25, 32, 38.

41 The “eleven basic needs” identified by the Ministry of Human Settlements were livelihood, water, food, power, clothing, health care, education, culture and technology, ecological balance, sports and recreation, shelter and mobility. See “BLISS: The Human Settlements Revolution” (1979, pp. 26–27, 33).

42 For recent water shortages in Metro Manila under the presidency of Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III due to low levels in Bulacan’s Angat Dam, see Maila Ager, 2010; Christian V. Esguerra, 2010.

43 Ng, 2001, par. 8.

44 Ibid., par. 7.

45 Brown writes: “not only is the human being configured exhaustively as homo oeconomicus, all dimensions of human life are cast in terms of a market rationality. While this entails submitting every action and policy to considerations of profitability, equally important is the production of all human and institutional action as rational entrepreneurial action, conducted according to a calculus of utility, benefit, or satisfaction against a micro-economic grid of scarcity, supply and demand, and moral value-neutrality” (2003, par. 9).

46 Ibid., par. 15.

47 Ibid.

48 Kubrador and its filmmakers have won numerous awards both nationally and internationally. In the Philippines, Jeturian is the recipient of the 2006 Lino Brocka Award at the Cinemanila International Film Festival; Kubrador also swept the awards for Best Picture, Best Direction, and Best Production Design in the 2007 Gawad Urian Awards and Best Director, Best Editing, Best Motion Picture Drama, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Sound in the 2007 Golden Screen Awards. Internationally, Kubrador won the 2006 FIPRESCI Prize at the Moscow International Film Festival; Best Film at the 2006 Cinefan Festival of Asian and Arab Cinema; and the 2007 NETPAC Award at the Brisbane International Film Festival.

49 The opening intertitles of Kubrador read: “‘Jueteng’ is a numbers game in the Philippines. Though illegal, it is popular especially among the poor. Millions of people depend on jueteng for their livelihood. It is so lucrative that the big jueteng operators are said to wield undue influence over politicians, the military, the police, and even the church. In the year 2000, the President of the Philippines was charged with accepting pay-offs from jueteng, and was subsequently deposed. More recently, the current president, her husband, and son, were also accused of having links to jueteng.” Estrada was found guilty of plunder in 2007. Six weeks later, he avoided serving a life sentence in the national penitentiary through a presidential pardon from Arroyo. Critics charged that Arroyo’s use of executive clemency was calculated “to curry favor with the opposition and to deflect mounting charges of corruption within her own administration” (Avendaño and Uy 2007). http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/inquirerheadlines/nation/view/20071026-96809/Arroyo_pardons_Estrada

50 Jeturian notes that the film’s allusions to the role of jueteng in Philippine politics “helps in relaying the message that the government is in cahoots with it; in fact, they’re a big part of it. Campaign funds, they come from jueteng, like with ‘Erap.’” Jeturian, interview with author.

51 According to Jeturian, Kubrador was shot on location in Quezon City at Barangay Botocan, Diliman, near the BLISS housing project that provided the setting for Pila Balde. Signage for “Pook Libis, Diliman” is visible in some shots of Kubrador.

52 Jeturian, interview with author.

53 For her performance in Kubrador, Gina Pareño has won two Best Actress awards locally (the 2007 Gawad Urian and 2007 Golden Screen awards) and three Best Actress awards in international film festivals: the 2006 Amiens International Film Festival; the 2006 Cinefan Festival of Asian and Arab Cinema; the 2007 Brussels International Independent Film Festival.

54 According to Jeturian, the practice of converting or translating experiences into betting values came to his attention in preproduction research, when the filmmakers interviewed an actual jueteng kubrador. Jeturian, interview with author.

55 Jeturian, interview with author.

56 Jeturian, interview with author.

57 Christian Sorace, 2010.

58 The Philippine economy’s reliance on ever-increasing remittances by Filipino migrant workers is staggering: remittances from overseas Filipino workers (OFW) grew from 7.5 billion pesos in 1998 to 8.5 billion dollars in 2004 (a sum equal to half of the country’s national budget), and $15.56 billion dollars in 2008. E. San Juan Jr. writes, “In 2006, the OFW remittance was five times more than foreign direct investment, 22 times higher than the total Overseas Development Aid, and over more than half of the gross international reserves. Clearly the Philippine government has earned the distinction of being the most migrantand remittance-dependent ruling apparatus in the world, mainly by virtue of denying its citizens the right to decent employment at home” (2009, p. 100).

59 Brown, 2003, par. 22.

60 For a discussion of the neoliberal concept of individualism and self-interest, see Morgan, 2003, pp. 543–544.

61 Ng, 2001, par. 17 and 19.

62 Enrile, 2009, pp. 66– 67.

63 Jet Damaso, 2006.

64 For Bourdieu, neoliberalism is a “screen discourse” that tends “to make a transnational relation of economic power appear like a natural necessity.” See Pierre Bourdieu and Loic Wacquant, 2001, par. 5– 6.

65 Giroux, 2005, p. 9.

Bibliography

Ager, Maila. “Water Shortage hits 50 percent of Metro Manila.” Philippine Inquirer, July 20, 2010. http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/topstories/topstories/view/20100720–282193/Water-shortage-hits-50—of-Metro-ManilaDPWHChief.

Avendaño, Christine, and Uy, Jocelyn. “Arroyo pardons Estrada.” Philippine Inquirer, October 26, 2007. http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/inquirerheadlines/nation/view/2007102696809/Arroyo_pardons_Estrada.

“BLISS: The Human Settlements Revolution.” Focus Philippines, June 23, 1979.

Bordwell, David, and Kristin Thompson. Film Art: An Introduction. 8th ed. Boston: McGraw Hill, 2008.

Bourdieu, Pierre, and Wacquant, Loic. “New Liberal Speak: Notes on the New Planetary Vulgate.” Radical Philosophy 105 (January–February 2001): par. 5–6. http://www.radicalphilosophy.com/default.asp?channel_id=2187&editorial_id=9956.

Brown, Wendy. “Neo-Liberalism and the End of Liberal Democracy.” Theory and Event 7, no. 1 (2003). http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/theory_and_event/v007/7.1brown.html.

Dalangin-Fernandez, Lira. “Arroyo Urged: Enact Lower Amusement Tax Law.” Philippine Inquirer, March 16, 2009. http://showbizandstyle.inquirer.net/breakingnews/breakingnews/view/20090316–194479/Arroyo-urged-Enactlower-amusement-tax-law.

Damaso, Jet. “Jeturian’s Gamble Pays Off.” BusinessWorld, August 18, 2006.

Elley, Derek. “Fetch a Pail of Water.” Variety, December 11, 2000. http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117796939.html?categoryid=31&cs=1.

Elliott, Dorinda. “The Newest Asian ‘Tiger’: The Philippines Is Learning, at last, How to Prosper without Depending on the United States.” Newsweek, December 2, 1996. http://www.newsweek.com/id/103502.

Enrile, Annalisa Vicente. “The Bet Collector.” Visual Anthropology 22 (2009): 66—67.

Esguerra, Christian V. “Water Crisis Splits Gov’t.” Philippine Inquirer, July 22, 2010. http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/inquirerheadlines/nation/view/20100722–282442/Water-crisis-splits-govt.

Garcia, Roger. “The Art of Pito Pito: Art Movie Poetics Meet Pulp Rage in the Shoestring Epics of Filipino Filmmaker Lav Diaz.” Film Comment 36, no. 4 (July–August 2000): 53–55.

Giroux, Henry A. “The Terror of Neoliberalism: Rethinking the Significance of Cultural Politics.” College Literature 32, no. 1 (Winter 2005): 1–19.

Lim, Bliss Cua. “Crisis or Promise: New Directions in Philippine Cinema.” IndieWire, August 14, 2000. http://www.indiewire.com/article/festivals_crisisorpromisenewdirectionsin_philippine_cinema.

Lim, Bliss Cua. “In the Navel of the Sea Shines at Filipino Film Showcase.” IndieWire, September 9, 1998. http://www.indiewire.com/film/festivals/fes_98Filip_980909_InNavel.htm.

Linden, Eugene. “How to Kill a Tiger: Speculators Tell the Story of Their Attack against the Baht, the Opening Act of an Ongoing Drama.” Time, Time Asia edition, November 3, 1997.

Lopez, Iskho F. “Festival Time at the Movies.” BusinessWorld, June 11, 1999.

Lukács, Georg. “Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat.” In History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics, translated by Rodney Livingstone, 92. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1968.

Martinez-Belen, Crispina. “Law Reduces Film Amusement Tax to 10 percent.” Manila Bulletin, August 4, 2009. http://www.mb.com.ph/articles/214294/lawreduces-film-amusement-tax-10.

Melencio, Sonny. “Collapse of The Philippine Peso: Who’s the Culprit?” Green Left Weekly, September 25, 1997. http://www.greenleft.org.au/1997/291/15906.

Morgan, Jamie. “Words of Warning: Global Networks, Asian Local Resistance, and the Planetary Vulgate of Neoliberalism.” positions 11, no. 3 (2003): 541–554.

Ng, Yvonne. “Director Jeffrey Jeturian in Conversation with Yvonne Ng.” Kinema (Spring 2001). http://www.kinema.uwaterloo.ca/article.php?id=150&feature.

Nolledo, Wilfrido D. “A Human Settlement for the Tao.” Focus Philippines, June 23, 1979.

San Juan, E.“Overseas Filipino Workers: The Making of an Asian-Pacific Diaspora.” The Global South 3, no. 2 (Fall 2009): 99–129.

Sorace, Christian. “Interview with Wendy Brown.” Broken Powerlines, February 20, 2010. http://www.brokenpowerlines.com/?p=12.

Vera, Noel. “The First Good Filipino Film of the Year.” BusinessWorld, June 4, 1999.