Liszt’s first encounter with Italy has been told time and again in various guises: as a romance, a travelogue, and a Bildungsroman.1 Italy’s breathtaking beauty has been credited with luring him over the Alps. As Chateaubriand once said, “Nothing is comparable to the beauty of the Roman horizon, to the sweet inclination of the plains as they meet the soft and flowing contours of the hills.”2 Such sensual descriptions attracted many visitors to Italy, but there was more to Liszt’s travels than scenic diversion. When he journeyed south in 1837, he joined a steady stream of artists, aristocrats, writers, and musicians who for centuries had made the long and difficult trip. Like these travelers, Liszt was drawn by Italy’s reputation as the cradle of European culture, by the beauty of its art, and by the mystery of its past. Although it is true that he was in the middle of a scandalous relationship with Marie d’Agoult when he journeyed south with her, this was old news; their first child had already been born, in 1835. Liszt was escaping more than mere gossip when he left Paris. He was on a quest to discover his creative essence, a new artistic identity. Liszt had a “premeditated master plan” concerning the future course of his career, and during the second half of the 1830s he planned on “distinguishing himself” in intellectual pursuits that were accorded more prestige than mere performing—namely composition and literature.3 Italy offered beauty and comfort; but more important, it held the promise of an intellectually rich escape.

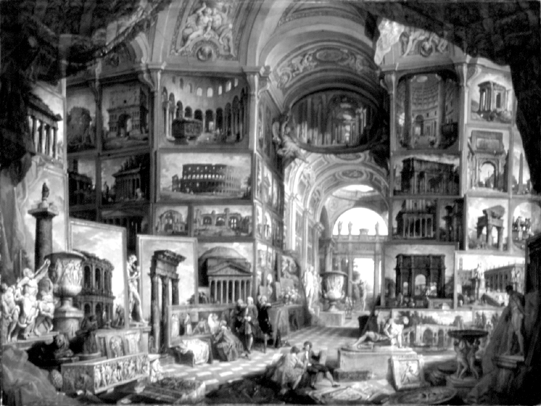

The image of Italy as a destination for the cultured and well educated took shape in the mid-eighteenth century. Painters such as Canaletto captured the beauty of Italian cities and landscapes, and archaeological excavations across the peninsula fueled a growing interest in antiquity. Scholars like Johann Joachim Winckelmann in Germany and Comte Anne-Claude-Philippe de Caylus in France pondered Italy’s ancient past. Their studies drew countless travelers from across Europe, and the Grand Tour became a required activity in the education of every “European gentleman.” Rome, in particular, served as a living textbook—the undisputed capital of the visual arts (figure 1).4 Some scholars have described Liszt’s first journey to Italy as his own Grand Tour.5 This description is valid as far as it goes, since it is clear that Liszt sought an education of sorts as he traveled. But self-enlightenment was not at the core of his motivation. Simply put, Liszt traveled to Italy to escape his own past. Troubled by the music politics he had recently experienced in Paris, he sought refuge, and Italy seemed the perfect sanctuary.

Scholars have mapped every step of Liszt’s journey, from the moment he first crossed the Alps to his twilight days in Tivoli late in life. My goal is somewhat different. Instead of describing “Liszt in Italy,” I reflect on the image of Italy he alluded to in his music, specifically the second volume of his Années de pèlerinage (Years of pilgrimage)—Deuxième Année: Italie (Second year: Italy).6 Liszt published this work in 1858, three years after Première Année: Suisse (First year: Switzerland), appeared.7 The first volume consists of nine pieces, all of which are related to impressions of nature and scenic Swiss locales. In contrast, the Italy volume contains seven pieces directly related to the visual arts and poetry of early-modern Italy:

“Sposalizio” (a painting by Raphael)

“Il penseroso” (a sculpture by Michelangelo)

“Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa”

“Sonetto 47 del Petrarca”

“Sonetto 104 del Petrarca”

“Sonetto 123 del Petrarca”

“Après une lecture du Dante (Fantasia quasi Sonata)”

In addition to revealing the art and literary works Liszt encountered in Italy, year two of Années de pèlerinage roughly replicates the itinerary he followed, from Milan and Venice to Florence and Rome.8 By the time he crossed the Alps, these cities had become reputed havens for political and social exiles. The end of the Napoleonic era marked a new chapter in the region’s history. Humbled politically, Italy had become a cultural refuge, “the Paradise of Exiles” as Shelley described it in 1824.9 Lord Byron had much to do with the creation of this image. In the final installment (Canto IV) of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (published in 1818), Byron blended the popular image of the poet as rebel and bearer of freedom with that of the social outcast and solitary wanderer. Italy offered self-exiles like Liszt a new start—a chance to face up to his mission as a “poet” in the Romantic sense of the word and define his artistic identity as an expatriate in a foreign land.

Various pieces in the first two volumes of Années de pèlerinage are framed by quotations from Cantos III and IV of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. Like Byron, Liszt consciously created a public image of himself as a lone pilgrim, an intellectual “poet” whose travels across Switzerland served as the scenic prelude to a full artistic awakening in Italy. Liszt presented this Byronic image of himself to Parisian readers through a series of articles (commonly referred to as Lettres d’un bachelier ès musique) published in Revue et Gazette musicale de Paris and L’Artiste during his years abroad. The authorship of these articles has been a topic of debate for nearly a century. Although Liszt’s name appeared as the sole author, even he acknowledged that d’Agoult sometimes contributed to their production. To date, Rainer Kleinertz has given the most even-handed assessment of the Liszt-d’Agoult authorship issue. In the commentary to his edition of Liszt’s complete writings, Kleinertz describes d’Agoult’s contributions to various article drafts written between 1837 and 1841 and, in so doing, convincingly demonstrates that the overall structure and content of the articles should be attributed primarily to Liszt.10 Charles Suttoni expressed a similar opinion in his own study of Liszt’s literary works, claiming that they were the result of “an active and fluid literary partnership” where “Liszt’s ideas” were at times “expressed in d’Agoult’s words.”11 Despite their authorship, Liszt’s articles drew attention to his travel experiences and intellectual inquiries—they also highlighted many of the literary and artistic influences that later defined his Années de pèlerinage.

Figure 1. Giovanni Paolo Panini, Roma Antica, or Views of Ancient Rome with the Artist Finishing a Copy of the Aldobrini Wedding. Stuttgart, Staatsgallerie.

In recent years, scholars interested in Liszt’s Années de pèlerinage have concentrated on purely musical aspects, namely the composition’s genesis and form.12 My approach is markedly different. Focusing on the extra-musical origins of the Italy volume, I describe in detail the cultural and historical circumstances that informed Liszt’s reception of Italian art and literature. As I hope to demonstrate, the literary and artistic sources Liszt encountered during his travels across Italy profoundly influenced his self-image as a composer and his creation of Années de pèlerinage. In Liszt’s mind, Italy became part of an ideal landscape that I call the Republic of the Imagination. This term is closely tied to George Sand’s descriptions of a “republic of music” and “holy colony of artists” in her letters to Liszt.13 When Sand coined these ideas in the early 1830s, their political resonance was especially strong, and my use of the phrase Republic of the Imagination makes reference to this.14 Sand’s ideas clearly influenced Liszt’s perception of Italy; his Republic of the Imagination was a state of mind, an imaginary place where artists, writers, and musicians interacted freely, unbound by political or historical ties. Specifically, it was a creative space where Liszt interacted with an imagined community of artists derived from early-modern Italian art and literature.

Like many northern travelers before him—including Goethe, Byron, and Heine—Liszt toured Switzerland before venturing on to Italy.15 Sand wrote to him at this time, describing the “divine” inspiration she knew he would find there. Encouraging him to forget about music politics in Paris, she recommended he join the “holy colony of artists” and pledge allegiance to the metaphorical “republic” of music—a land that would be revealed to him via the wondrous beauty of nature.16 Liszt attempted to follow her advice, but as he explained in a response published in the Revue et Gazette musicale in December 1835, he was unable “to fathom the treasures of the snow” as she had. “The wall-nettles, bindweeds, and harts’ tongues” that had whispered “harmonious secrets” in her ear, remained silent in his presence. Liszt was at a loss, and he described his state of mind in great detail:

The republic of music, already established by a leap of your young imagination, is still only a dream for me…. I blush with shame and confusion when I reflect seriously on my life and pit your dreams against my realities:…your noble presentiments, your beautiful illusions about the social effects of the art to which I have dedicated my life, against the gloomy discouragement that sometimes seizes me when I compare the impotence of the effort with the eagerness of the desire, the nothingness of the work with the limitlessness of the idea;—those miracles of understanding and regeneration wrought by the thrice-blessed lyre of ancient times, against the sad and sterile role to which it is seemingly confined today.17

Liszt’s self-doubt was exacerbated by the fact that Sigismond Thalberg had recently descended on Paris and was being hailed as “le premier pianiste du monde.”18 Intent on confronting this new “mysterious rival,” Liszt postponed his travel plans to Italy and returned to Paris.19 On 8 January 1837, he published a mean-spirited review of Thalberg’s music in the Revue et Gazette musicale. This article angered many of Liszt’s colleagues, especially the critic François-Joseph Fétis, who later came to Thalberg’s defense in an article of his own.20 Reactions such as this turned Liszt into something of a pariah in Parisian musical politics, and he soon took up his pen again—this time in the guise of a persecuted artist. In an article addressed “To a Poet-Voyager” (i.e., George Sand), Liszt expressed his desire to escape.21 Using language strikingly similar to that found in Madame de Staël’s novel Corinne ou Italie, he lamented Italy’s political misfortune and explained why it was the perfect refuge for “those exiles from heaven,” like himself, “who suffer and sing” all in the name of “poetry”:

Italy! Italy! The foreigner’s steel has scattered your noblest children far and wide. They wander among the nations, their brows branded with a sacred curse. Yet no matter how implacable your oppressors might be, you will not be forsaken, because you were and will always be the land of choice for those men who have no brothers among men, for those children of God, those exiles from heaven who suffer and sing and whom the world calls “poets.”

Yes, the inspired man—philosopher, artist, or poet—will always be tormented by a secret misfortune, a burning hope in your regard. Italy’s misfortune will always be the misfortune of noble souls, and all of them will exclaim, along with Goethe’s mysterious child: DAHIN! DAHIN!22

Liszt had chosen Italy as his destination, and in a later article he described, in language clearly influenced by Byron’s Childe Harold, his destiny as a vagabond artist:

It behooves an artist more than anyone else to pitch a tent for only an hour and not to build anything like a permanent residence. Isn’t he always a stranger among men? Isn’t his homeland somewhere else? Whatever he does, wherever he goes, he always feels himself an exile…. What then can he do to escape his vague sadness and undefined regrets? He must sing and move on, pass through the crowd, scattering his works to it without caring where they land, without listening to the clamor with which people stifle them, and without paying attention to the contemptible laurels with which they crown him. What a sad and great destiny to be an artist!23

These are the sentiments of a man in crisis. “I have just spent the past six months living a life of shabby squabbles and virtually sterile endeavors,” Liszt lamented. “Day by day, hour by hour, I endured the silent tortures of the perpetual misunderstanding that… exists between the public and the artist.”24 Liszt felt isolated, unsure of the future. As Dana Gooley explains, the Parisian public had not fully embraced his approach to virtuosity, which was “aimed at the sensibilities of the literati, the artistes.” Liszt, according to Gooley, had asked his audiences “to listen in new ways,” and this had “presented a challenge to his general acceptance.”25 He believed that his approach to music was in need of more public support, a stronger sense of community. These were things that the visual arts had already achieved, and Liszt looked to them with envy:

Among all the progressive ideas I dream about, there is one that should be easy to implement and that came to me a few days ago when, strolling silently through the galleries of the Louvre, I was able to survey, one after the other, the profoundly poetic brushstrokes of Scheffer, the gorgeous colors of Delacroix, the pure lines of Flandrin, of Lehmann, and the vigorous scenes of Brascassat. I asked myself: Why Isn’t music invited to participate in these annual festivals?…How is it that composers do not bring the finest flowers of their calling here as do the painters, their brothers?26

Liszt had recently attended the Paris “Salon,” a government-sponsored exhibit of works by contemporary French artists, and he dreamed of a similar opportunity for music. Most of the artists named in Liszt’s article were living together in Rome at the French Academy; the paintings they had sent back to Paris revealed the intellectual bond they shared. In Rome, these artists worked closely with one another; they shared studio space, models, and creative ideas. They read the same books, visited the same ancient sites, and often contemplated similar historic and literary themes in their art.27 Living together as a group of expatriates, they had been deemed by the French government to be the best in their field. Liszt revered these artists, and in Italy he hoped to find a similar artistic community for himself.28

Liszt and d’Agoult departed for Italy the first week of May 1837. As they journeyed south, they visited friends—George Sand in Nohant, and Lamartine at his country home, Saint-Pont—and traveled through Switzerland again as a prelude to Italy. On 17 August they reached their first stop in Italy—Baveno on the shore of Lake Maggiore—but quickly moved on. Liszt was eager to experience life in the major cities. He read voraciously and sought out noted musical figures as he traveled from one capital to the next. Certain key experiences connected with Liszt’s travels deserve to be highlighted, since they shaped his writing of the “Italy” volume of Années de pèlerinage and the formation of his Republic of the Imagination.

Shortly after his arrival in Italy, Liszt wrote three articles in quick succession that reveal much about his state of mind at the time. The first, addressed “To Adolphe Pictet,” begins with the query: “Where am I going? What will I become?”29 In response to these questions, Liszt described the “metaphysical fund” of ideas he had recently gained in the company of George Sand. With her his “activities and diversions” had been simple: “reading the works of some indigenous thinker or profound poet (Montaigne or Dante, Hoffmann or Shakespeare).” Literature fueled Liszt’s imagination, and he composed regularly, looking to the piano as an inextricable part of his creative voice: “My piano is to me what a ship is to the sailor, what a steed is to the Arab, and perhaps more because even now my piano is myself, my speech, my life.”30 According to Liszt, creating music was an act of communication, a cooperative effort. Great artists never worked in isolation—the input of many could be heard in a single composition: “Certain authors, when speaking of their works, say my book, my commentary, my account, etc…. They would do better to say our book, our commentary, our account, etc., seeing that there is usually more of other people’s work than their own therein.”31

Liszt elaborated on this idea of communal inspiration in his next article, “To Louis de Ronchaud.”32 Here Lamartine, “the happy poet of the age,” served as his role model. Although Chateaubriand “gloriously established a new literature in France,” it was Lamartine who had “the gift of knowing just how far innovation can go.” Lamartine appealed to those “basically subjective readers who love to find themselves reflected in everything and thus can easily inject their own stories into the harmonious framework of his divine poetry.”33 This was clearly shown in his Méditations poétiques, published in 1820. Liszt greatly revered this collection. For the first time in French literature, Lamartine presented poetry not as an art of pure form (wherein the message was secondary to the formal poetic structure) but as a mode of earnest communication. In these works Lamartine appeared to speak plaintively from the heart about his personal reflections on art, nature, and love. One poem in particular, “Philosophie,” must have appealed to Liszt as he traveled across Italy. In this work Lamartine mixed a desire to escape “to the shores of the Arno” with an evocation of Petrarch and Dante. Like Byron, Lamartine took on the guise of an itinerant poet reflecting on life’s purpose and the inevitable passage of time.

Lamartine’s evocation of Petrarch and Dante in the opening stanza of “Philosophie” can be read as a commentary of sorts—a poetic reaction to the works of his Italian predecessors. As literary historian Robert Hollander explains, an outpouring of Dante commentaries swept across Europe during the early decades of the nineteenth century. Many of Liszt’s French colleagues, most notably Lamartine, Lamennais, Hugo, and Sand, looked to Dante as the Romantic poet of the great damned souls: “What Dante knew best how to portray, for these and other illustrious figures, was the passion of suffering.”34 This image of Dante excited Liszt, and he soon began writing his own commentaries. For example, in an article written in Septembe–-October 1837, he compared Dante’s depiction of Beatrice in the Divine Comedy to his own conception of “woman sublime”:

I must confess that I have always been terribly disturbed by one thing in that immense, incomparable poem, and that is the fact that the poet has conceived Beatrice, not as the ideal of love, but as the ideal of learning. I do not like to see a scholarly theologian’s spirit inhabiting that beautiful, transfigured body, explaining dogma, refuting heresy, and expounding on the mysteries. It is certainly not because of her reasoning and her powers of demonstration that a woman reigns over a man’s heart. It is certainly not for her to prove God to him, but to give him a sense of God through love and thus lead him to heavenly matters. It is in her emotions, not in her knowledge, that her power lies. A loving woman is sublime; she is man’s true guardian angel. A pedantic woman is a contradiction in terms, a dissonance; she does not occupy her proper place in the hierarchy of beings.35

Liszt’s excursus reveals much about his concept of women at the time.36 His woman sublime was the ideal muse, a figure clearly derived from Goethe’s Faust. Liszt deeply respected d’Agoult’s mind and her talents as a writer, but if he ever conceived of her as his muse, it was not for these intellectual attributes.37 As he clearly explained, he sought a woman of undying devotion, “that beautiful, transfigured body” who could give him a sense of the divine through love. Liszt’s woman sublime, as we shall see, was a philosophical ideal, an inspirational muse, not the object of physical, earthly love. She had little to do with real-life experiences. Instead, she was an amalgam of the women Liszt encountered in Italian literature and painting, and as such she played a crucial role in year two of Années de pèlerinage.

Liszt went to Italy in search of inspiration, and as he visited the major cities, he sought out people he thought might share his creative interests. Chief among Liszt’s colleagues in Milan was Gioacchino Rossini, who had recently established a series of Friday night musicales in his home. As Rossini himself explained in a letter written during the height of Liszt’s participation, these soirées served as an open door to the elite of Milan’s musical society: “My musical evenings make something of a sensation…. Dilletantes, singers, maestri, all sing in the choruses; I have about 40 choral voices, not counting all the solo parts…. The most distinguished people are admitted to my soirées; Olympe does the honors successfully, and we carry things off well.”38

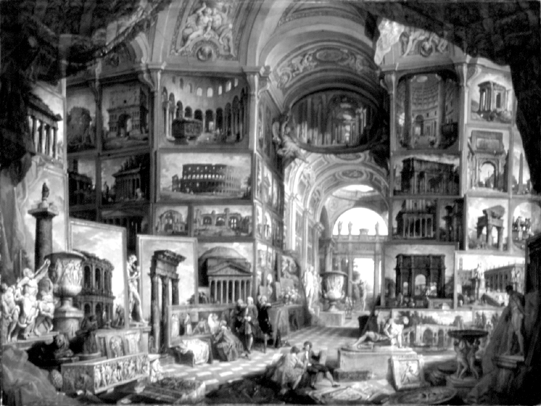

Among the many choral works performed at these events was Rossini’s Il pianto delle muse in morte di Lord Byron. Ricordi had published this canzone con coro in 1825, along with a virtuosic paraphrase for solo piano arranged by Rossini himself.39 Rossini’s homage to Byron drew little interest from his Italian compatriots, but it intrigued Liszt. As he explained in an article written in early 1838, Rossini was the only Italian composer who showed any real appreciation for literature. Unfortunately, he was also a slave to public opinion and consequently never realized his musico-poetic aspirations.40 The musical community Liszt found in Milan welcomed him, but it did not provide the intellectual stimulation he sought. Consequently, he turned to literature and art for inspiration. He visited the Milan cathedral, remembering that Madame de Stäel had defined music as “the architecture of sound,” and explored the treasures of the Brera.41 Liszt was struck by numerous paintings in Milan, but only one became part of his Années de pèlerinage: Raphael’s image of the Sposalizio—the Betrothal of the Virgin Mary and Joseph (figure 2).

Raphael’s painting is based on a parable recounted by Saint Jerome in the apocryphal “Protevangelium” and in Jacobus of Voragine’s thirteenth-century Legenda Aurea (The Golden Legend). Liszt would have known the story; it tells of the day when Mary came of age to wed. The high priest ordered all the unmarried male descendants of David to bring a wooden rod to the Temple of Jerusalem. When they arrived, the Holy Spirit descended in the form of a dove and caused Joseph’s rod to blossom, a sign that he had been chosen to become Mary’s husband.

It is easy to see why this painting appealed to Liszt. The Virgin’s clothes and stance give her the appearance of a classical muse. She is woman sublime—the “beautiful, transfigured body” that Liszt had evoked earlier when contemplating Dante’s Divine Comedy. In contrast, Joseph appears as a mere mortal, with downcast eyes and bare, deformed feet. He is the chosen one, the recipient of God’s blessing and Mary’s devotion. Borrowing language from Liszt’s own description of ideal love in relation to Dante’s Beatrice and woman sublime, one can interpret the scene in Raphael’s painting as a metaphor for divine inspiration: as the Virgin accepts Joseph’s ring, she “gives him a sense of God through love and thus leads him to heavenly matters.” Raphael’s figures do not appear in the real world; they reside in an ideal, utopian landscape. Nonetheless, symbols of the real world do exist: a Bramante-inspired temple anchors the scene, its open door framing the vanishing point and leading the eye upward into the infinite sky beyond. Inscribed above the door is Raphael’s signature (RAPHAEL URBINAS MDIIII), a reminder to viewers that what they see is neither reality nor fantasy, but an artwork. To nineteenth-century viewers, Raphael’s Sposalizio was a vision of inspiration personified, a testament to the artistic link between man’s spiritual present and the historic past.42

Figure 2. Raphael, Sposalizio. Milan, Brera Museum.

Liszt’s interest in art persisted as he made his way to Venice in March 1838. According to d’Agoult, the city captivated him immediately: “He was absorbed by its canals, its bridges, and the play of the light across its unique architecture.”43 Liszt visited the Piazza San Marco, La Fenice, the art galleries, churches, and the Doge’s Palace. He sought out every tourist highlight, and even hired as his guide a gondolier named Cornelio, who claimed to have shown Byron the same sights years before. Venice sparked Liszt’s imagination, as is clearly shown in the essays he wrote shortly after his arrival. In an article “To Heinrich Heine,” Liszt described his new state of mind through a Byronic evocation of the city’s “poetic desolation”:

Have you ever been to Venice? Have you ever glided on the sleepy waters in a black gondola down the length of the Grand Canal or along the banks of the Giudecca? Have you felt the weight of centuries crushing down on your helpless thoughts? Have you breathed that turgid, heavy air that presses you and thrusts you down into inconceivable languor? Have you seen the moon cast its pale rays on the leaden domes of old Saint Mark’s? Did your ear, uneasy about the deathly silence, ever seek out some sound, just as the eye seeks out the light in the darkness of the dungeon? Yes, no doubt about it. Then you are familiar perhaps with the most poetic desolation in the world.44

Much has been written about Liszt’s first visit to Venice—especially his learning of the disastrous floods in Hungary and his consequential departure for Vienna.45 What has not been thoroughly discussed, however, is the manner in which Liszt later reflected on his trip to Austria and the circumstances that preceded his departure. Liszt’s purported sudden desire to come to the rescue of his homeland, Hungary, was intimately tied to his experiences in Italy: his interest in Byron, his search for art’s role in society, and his longing for a new form of intellectual community. In a two-part article “To Lambert Massart,” written in the summer of 1838, Liszt explained, albeit in a coded manner, how his experiences in Italy and success in Vienna had led to a transformation of his artistic identity.46 Although both parts of the article were written after Liszt returned from Vienna, the text itself is arranged in a “before and after” format. Part one describes Liszt’s state of mind before learning of the floods in Hungary; part two gives a description of his experiences in Vienna and his new artistic identity.

At first glance, part one of the article appears to be just another description of Milan’s music scene. But what begins as a routine account of a soirée in the home of Julia Pahlen-Samoyloff soon digresses into a dream sequence.47 Leaving the chaos of “reality” in the Milanese ballroom, Liszt ventures into an unknown landscape, a fantastical realm that is clearly located in his Republic of the Imagination:

I left the ballroom and went in search of a secluded, unoccupied corner where I could be alone…I sat down in a huge armchair whose black carvings and Gothic forms carried my imagination to a past age, while the scent of the exotic flowers conjured up images of distant climes. I do not know if my imagination…caused me to see a startling, supernatural apparition. All I know for certain is that I very quickly lost all sense of reality, all feeling for time and place, and that I suddenly found myself wandering all alone in an unknown land on a deserted beach beside a stormy sea.48

Trapped in the middle of this desolate landscape, Liszt discovers that he is not alone. Ahead of him is “a pensive figure…walking along the sand.”

He was still young, although his face was pale, his look intense, and his cheeks haggard. He stared at the horizon with an indescribable expression of anxiety and hope. A magnetic force drew me after him…. The farther I went, the more it seemed to me that my existence was linked to his, that his breath animated my life, that he held the secret of my destiny, and that we, he and I, had to merge with and transform each other…. “Oh, whoever you are,” I cried, “… [you], who has fascinated and taken complete possession of me, tell me, who are you? Where do you come from? Where are you going? What is the reason for your journey? What are you seeking? Where do you rest?…Are you a condemned man under an irrevocable sentence? Are you a pilgrim filled with hope eagerly traveling to a peaceful, holy place?”49

In the past, scholars have avoided identifying this pensive figure. I propose that he is none other than Childe Harold himself, as he appeared in the early stanzas of Canto I:

And now Childe Harold was sore sick at heart,

And now Childe Harold was sore sick at heart,

And from his fellow bacchanals would flee;

’Tis said, at times the sullen tear would start,

But Pride congeal’d the drop within his e’e:

Apart he stalked in joyless reverie,

And from his native land resolved to go,

And visit scorching climes beyond the sea;

With pleasure drug’d he almost long’d for woe,

And e’en for change of scene would seek the shades below.50

Liszt’s apparition holds “an oddly shaped musical instrument whose bright, metallic finish shone like a mirror in the rays of the setting sun.” This is further proof that the stranger is Childe Harold, for he too carried a harp when he first set sail on his pilgrimage:

But when the sun was sinking in the sea

He seized his harp, which he at times could string,

And strike albeit with untaught melody,

When deem’d he no strange ear was listening:

And now his finger o’er it he did fling,

And tun’d his farewell in the dim twilight.

While flew the vessel on her snowy wing,

And fleeting shores receded from his sight,

Thus to the elements he pour’d his last “Good night.”51

The stranger in Liszt’s dream tries to bid him “Adieu,” but Liszt refuses to leave. As the stranger describes the circumstances that have instigated his pilgrimage, we realize that they are startlingly similar to Liszt’s own:

I come from a distant land that I can no longer remember…. For a long, long time…I was disgusted by an earth so empty of blessings, so full of tears. I quickened my steps. I walked, walked ceaselessly, looking toward the distant horizon for my unknown homeland.

So far it has all been in vain. I yearn, I sense the future, but nothing is apparent yet. I do not know if after all this time I am coming to the end of my journey. The force that drives me is silent; it tells me nothing of my path.

At times the breeze coming over the water carries ineffable harmonies to me; I listen to them rapturously, but as soon as I think they are coming nearer, they are smothered by the discordant din of human strife….

If it is a malevolent force that harasses and torments me, why these divine dreams, these inexpressible, voluptuous floods of desire? If it is a beneficent power that is drawing me to it, why does it leave me in anguish and doubt, with the pangs of a hope that is always alive yet always thwarted?52

Liszt awakens from the dream and quickly makes his way home—all his friends can see that he has been visited by “that Demon of inspiration.” With the memory of his encounter fresh in his mind, Liszt sits down at the piano, where he enters the Republic of the Imagination once again. Like Childe Harold, he is a pilgrim wandering in search of a homeland; and at the piano, he discovers another traveler on a similar quest, Schubert’s “Wanderer”:

“Der Wanderer” came to mind, and that song, so sad and so poetic, affected me more than it ever had before. I seemed to sense a tenuous and secret analogy between Schubert’s music and the music I had heard in my dream.53

Liszt’s description of his encounters with Childe Harold and the Wanderer serves to explain his state of mind before traveling to Vienna. As he claims in part two of the article, he supposedly found part one “lying forgotten on the writing table” when he returned to Venice in June 1838. Part two is presented as having been written a month or so later as an extended postscript—the purpose being to explain what had happened to Liszt since that fateful night in Milan.

In the opening of part two, Liszt describes how he “was badly shaken” by news of the disaster in Hungary: “The surge of emotions revealed to me the meaning of the word ‘homeland.’ I was suddenly transported back to the past, and in my heart I found the treasury of memories from my childhood intact.” No longer a rootless wanderer like poor Childe Harold, Liszt “exclaimed his patriotic zeal” and reveled in the thought that he, too, was “a son” of Hungary. But as much as this article is a proclamation of Liszt’s allegiance to Hungary, it is also a public rebuke of France. Throughout part two, Liszt makes a point of separating his new identity from the “time of burning fever, misdirected energy, and vigorous, mad vitality on French soil.”54 Parisian music politics no longer concerned him. Liszt claimed to have found a new sense of purpose in Vienna, and at the end of the article, he included a final reference to Byron. Upon bidding his reader “Adieu” Liszt claimed to be “rushing to get the whole package in the post” in order to refrain from giving “a parenthetical account of a voyage to Constantinople.”55 Liszt had not yet traveled to Constantinople, but Childe Harold had, in Canto II of his Pilgrimage.

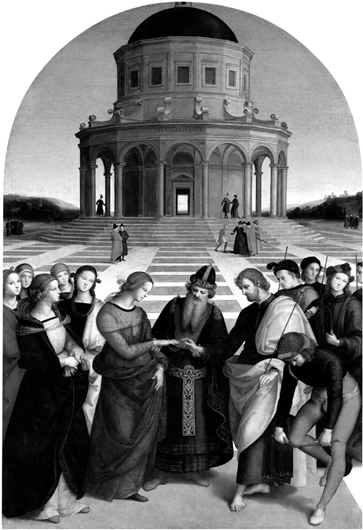

Liszt spent the winter of 1838–39 in Florence, and while there toured various art galleries and churches in search of creative inspiration. Upon visiting the tombs of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino (1492–1519) and Giuliano de’ Medici, Duke of Nemours (1479–1516) in the Medici Chapel in the Church of San Lorenzo, Liszt was struck by Michelangelo’s visual depiction of the contemplative man versus the man of action.56 The Medici Chapel consists of two large wall tombs facing each other across a high, domed room. One was designed for Giuliano de’ Medici (the son of Lorenzo the Magnificent), the other for Giuliano’s nephew, Lorenzo de’ Medici (the grandson of Lorenzo the Magnificent). Michelangelo conceived of the two tombs as representing opposite types: Giuliano symbolized the active, extroverted personality; Lorenzo, the contemplative, introspective one. As we know from Liszt’s Années de pèlerinage, he was most strongly drawn to Michelangelo’s image of Lorenzo, Il penseroso (figure 3).57

Michelangelo created Il penseroso as a man deep in thought, removed from the world of earthly goods and concerns. This is clearly indicated by Lorenzo’s gestures: his helmet and furrowed brow shadow his features. His left elbow rests on a closed cashbox, the index finger of his hand covering his mouth in a gesture of silence. To further strengthen the symbolism, Michelangelo adorned Lorenzo’s cashbox with a bat—a popular symbol for melancholia.58 This final trait, perhaps more than any other, confirms the artist’s interest in Neoplatonism. According to Panofsky, “among all his contemporaries,” Michelangelo was the only one who adopted key aspects of Neoplatonism as “a metaphysical justification of his own self.”59 Early-modern Neoplatonists such as Marsilio Ficino (1433–99) and Pico della Mirandola (1463–94), contemporaries of Michelangelo, argued that melancholy could be interpreted as a sign of intellectual prowess, even genius. They recalled Aristotle’s remark that all geniuses are melancholy, and were largely responsible for developing the modern concept of genius that later pervaded nineteenth-century literature.60

Upon seeing Michelangelo’s tombs for the Medici dukes, Michelangelo’s contemporary, Giovan Battista Strozzi the Elder (1505–71), composed a sonnet in praise of the female figure Notte (Night) who rests in front of the “active man” Giuliano de’ Medici:

Figure 3. Michelangelo, Il penseroso. Florence, Medici Chapel.

| La Notte, che tu vedi in sì dolci atti | The Night that in such a graceful attitude you see |

| dormir, fu da un Angelo scolpita in questo sasso, e perchè dorme ha vita: | sleeping, was sculpted by an Angel in this stone, and since she sleeps, she must have life; |

| Destala, se nol credi, e parleratti. | wake her, if you don’t believe it, and she’ll speak to you. |

In response to Strozzi (a man whose politics Michelangelo disdained) Michelangelo wrote a quatrain, full of bitterness, which made a veiled reference to the recent collapse of the Florentine republic:

| Caro m’e il sonno, e più l’esser di sasso | Dear to me is sleep; and more dear to be made of stone |

| Mentre che’l danno e la vergogna dura. | As long as there exists injustice and shame. |

| Non veder, non sentir m’è gran Ventura; | Not to see and not to hear is a great blessing to me; |

| Però non mi destar, deh! parla basso! | Therefore, do not disturb me! Speak softly!61 |

Liszt clearly understood the message of this quatrain; the story of Strozzi, Michelangelo, and the Florentine republic was told time and again in nineteenth-century guidebooks.62 When Liszt published his Années de pèlerinage in 1858, he borrowed the quatrain originally associated with Michelangelo’s figure Notte and attached it to Il penseroso instead. By doing so, he altered, ever so slightly, the iconology of Michelangelo’s statue—in Liszt’s version the figure of “contemplative man” is enhanced by a shade of rebelliousness.63

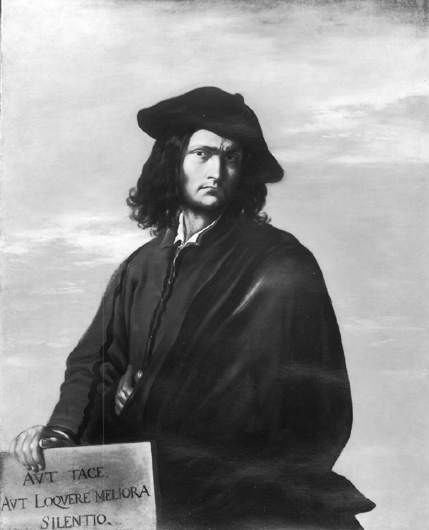

The theme of rebelliousness also played a role in Liszt’s interest in the works of Salvator Rosa (1615–73), one of the most original artists of the seventeenth century. Rosa’s works ranged from landscapes characterized by wild and mountainous beauty to macabre subjects and erudite philosophical allegories. In addition to his work as a painter, Rosa was a well-known poet of satire; a close relationship exists between his visual and literary works. Liszt probably first learned of Rosa through Parisian friends such as Berlioz and Alexander Dumas, père.64 Rosa was a popular figure in French literature during the 1830s, and in Florence, Liszt would have learned even more about Rosa’s fiery temperament, immense ambition, and intellectual prowess.65 Rosa had been part of a Florentine circle of intellectuals that included poets, historians, painters, scientists, and philosophers. His house was the meeting place for the Accademia dei Percossi, where members regularly read tributes to Rosa’s paintings and took part in theatrical performances. In 1830s Florence Rosa enjoyed a keen reception, most notably among the English community there. Myths and legends clustered around him, and it was widely believed that he had taken part in a popular uprising against the Spanish in Naples. These legends were immortalized in 1824 by Lady Morgan’s biography, The Life and Times of Salvator Rosa.66 Although there is no direct evidence that Liszt actually read this work, he no doubt was aware of the Rosa legend it had generated. Rosa had become an exemplar of the ideal artist: a noble exile and enemy of tyranny, whose wild genius was expressed in art and poetry and untrammeled by academic rules. According to Lady Morgan, Rosa was also a musician,67 and his activities as a composer strongly defined his artistic identity: “Music, the true language of passion, which speaks so powerfully, and yet so mysteriously…appears to have engrossed his undivided attention.” She even went so far as to claim that Rosa had discovered “a novel style of composition, expressively called la musica parlante” (spoken music) that proved to be “Il cantar che nel animo si sente” (the singing that one feels in the soul).68 Most important, Morgan defined music as Rosa’s primary means of artistic escape: “In his wayward and original mood…he betook himself to that school where no master lays down the law” and in so doing “felt proud and elated in the consciousness of the career he had struck out for himself, which left him free and unshackled in his high calling.”69

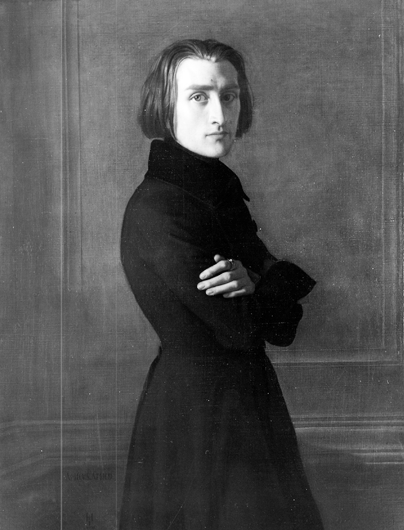

In addition to learning of Rosa’s supposed talents as a musician, Liszt would have become familiar with reproductions of the artist’s famous self-portrait (figure 4).70 Liszt’s good friend in Florence, the artist Henri Lehmann, knew this painting well, and I propose he looked to it as a model when designing his famous portrait of Liszt (figure 5).71 The parallels between these two paintings are clearly more than coincidence. The stances of Rosa and Liszt are similar, and the faces in both portraits are almost identical, from the shape and size of the eyes, nose, and chin to the play of light and shadow across their features. Rosa’s self-portrait strikingly illustrates his confidence as both an artist and an intellectual. Wearing a scholar’s cap and gown and a dark, forbidding expression, he points to a Latin inscription: “Keep silent, unless your speech is more profitable than silence.”72 Lehmann captured a similar mood in his portrait of Liszt. Concentrating on the composer’s lithe figure and penetrating gaze, he created a haunting portrait that exudes an air of confidence and mystery. A similar sense of confidence is expressed in the text of the “canzonetta” that Liszt transcribed for his Années de pèlerinage, believing mistakenly that it was a musical work by Rosa:

| Vado ben spesso cangiando loco | Often I change my location, |

| Ma non si mai cangiar desio. | But I shall never change my desire. |

| Sempre l’istesso sarà il mio fuoco E sarà sempre l’istesso anch’io. | The fire within me will always be the same And I myself will also always be the same. |

Figure 4. Salvatore Rosa, Self-Portrait. London, National Gallery.

More than a half-century has passed since Frank Walker revealed that this canzonetta was composed by Giovanni Battista Bononcini (1672–1750), not Rosa.73 But in Liszt’s day, “Vado ben spesso” was firmly tied to the artistic identity of Salvator Rosa. Both Charles Burney and Lady Morgan published the aria in their studies of Rosa.74 In Morgan’s description of the piece, the “desire” and “flame” referred to in the text were “construed as a vehement mixture of Romantic ideals,” not “the perennial commonplaces of Italian courtly love.”75

Figure 5. Henri Lehmann, Portrait of Liszt. Paris, Musée Carnavalet.

Liszt further reflected on the arts in a series of articles he wrote while living in Florence. This series can be divided into two separate groups: topical travelogues, published in the arts magazine L’Artiste, reflecting contemporary Italy; and philosophical articles rooted in Liszt’s Republic of the Imagination that appeared in the Revue et Gazette musicale. Of the various discussions presented in this latter group of articles, the most fascinating with respect to Liszt’s ideas concerning the role of the artist and the development of artistic communities are “The Perseus of Benvenuto Cellini” and “The Saint Cecilia of Raphael.” Liszt wrote his article on Cellini’s work in November 1838.76 He had obviously been reading Cellini’s autobiography, and it appears he was especially intrigued by Cellini’s account of how he had endured as an artist, despite public persecution. Liszt begins his article much like a novel, a sign that he is entering his Republic of the Imagination. It is two o’clock in the morning on a crisp September night. Liszt leaves a ball at the palace of Prince Poniatowski and “walks aimlessly along the Arno.” Quite by accident, he comes across Cellini’s Perseus, and the statue makes an “incomparably strong impression” on him: “I was detained by an invisible force. It seemed as if a mysterious voice was speaking, as if the statue’s spirit was talking to me.” Liszt tells the story of Perseus, which he considers to be “one of the beautiful myths of Greek poetry.” Perseus is a hero who prevailed in the “struggle between good and evil.” He is a man of genius who “seeks to unite himself with beauty, the poet’s eternal lover.”77

Once the story is laid out, Liszt discusses Cellini’s interpretation of the Perseus story and describes the regenerative effect literature can have on all the arts, generation after generation:

When initially assuming its most abstract form, art reveals itself in words. Poetry lends its language to art; it symbolizes art. In Perseus, antiquity gives us a profound, perfect allegory. It is the first stage, the first step, in the development of an idea…. In modern times and in the hands of a great artist, art takes on a perceptible form, it becomes plastic. The casting furnace is lit, the metal liquefies, it runs into the mold, and Perseus emerges fully armed, holding Medusa’s head aloft in his hand, the emblem of his victory.78

Liszt then moves on to a discussion of Berlioz’s place in this artistic continuum. Inspired by Cellini, who was inspired by Perseus, Berlioz composed his masterful opera in 1838. Layer upon layer, the tradition continues. An imagined community of artists, separated by time but united in thought and spirit, work together for the sake of art.

The other important article Liszt wrote in Florence, “The Saint Cecilia of Raphael,” was the result of a brief trip he took to Bologna in December 1838.79 The official purpose of this trip was to give a series of concerts, but as he explained in his article, the first item on his agenda was to visit the city’s museum: “I hurried right through three galleries…as I was anxious to see the Saint Cecilia.”80 d’Agoult had seen the painting a few months earlier, finding it to be “less laudable” than what she had expected.81 Liszt’s reaction was markedly different:

I do not know by what secret magic that painting made an immediate and twofold impression on my soul: first as a ravishing portrayal of the most noble and ideal qualities of the human form, a marvel of grace, purity, and harmony; and at the same instant and with no strain of the imagination, I also saw it as an admirable and perfect symbol of the art to which we have dedicated our lives.82

Like the Virgin in Raphael’s Sposalizio, Saint Cecilia appeared to Liszt as woman sublime. She also stood as “a symbol of music at the height of its power,” of “art in its most spiritual and holy form…. Like the inspiration that sometimes fills an artist’s heart,” Raphael’s personification of music was “pure, true, full of insight, and unalloyed with mundane matters.”83 Most important, it served as a font of inspiration for untold numbers of viewers:

Like all works of genius, his painting stirs the mind and excites the imagination of all those who ponder it. Each of us sees it in his own way and, depending upon his own makeup, discovers a novel form of beauty there, something new to admire and praise. That is precisely what makes genius immortal, what makes it eternally young, fertile, and stirring.84

Liszt saw in Raphael’s art the power of creative suggestion, an intellectual link from one artist to the next across time. So it should come as no surprise that as he continued his journey across Italy, his appreciation for literature and the visual arts began to manifest itself in his activities as a composer.

That Liszt was thinking about various works of art as creative fodder is evident from a journal entry made in February 1839, shortly after his arrival in Rome.85

If I feel within me the strength of life, I will attempt a symphonic composition based on Dante, then another on Faust—within three years time—meanwhile, I will make three “sketches”: The Triumph of Death (Orcagna), The Comedy of Death (Holbein), and a Fragment dantesque. Il Pensieroso [sic] bewitches me as well.86

As the above entry reveals, Liszt had mapped out plans for six separate programmatic compositions: the two symphonic pieces became his “Faust” and “Dante” symphonies, the “Triumph” and “Comedy” served as inspiration for his Totentanz Concerto, and “Il penseroso” and the “Fragment dantesque” became the second and last pieces in the Italy volume of Années de pèlerinage. As Rena Mueller explains, the genesis of the Italy volume is extremely complex.87 Early drafts of all the movements can be found in various sketchbooks and manuscripts, which indicate that Liszt worked on each movement separately and only later decided on the volume’s overall layout.88 In addition, it appears Liszt made a sketch for each movement, if not a complete draft, during the winter months of 1838–39.89

Rome was the culmination of Liszt’s Italian pilgrimage. During his five months there, from February through June 1839, he visited St. Peter’s, the Sistine Chapel, and the Vatican Museum. But the most important aspect of his stay in the capital was his interaction with artists at the French Academy. Liszt became something of an honorary fellow at the Academy, thanks to the influence of its director, Jean-August Ingres. Ingres was an accomplished violinist, and he spent countless evenings with Liszt performing chamber music, most notably that of Beethoven, at the Villa Medici. During the day, Ingres took Liszt and the pensionnaires at the French Academy on personal tours of Rome’s art galleries and museums.90 Liszt spoke about this newfound artistic fellowship in an article addressed “To Hector Berlioz.”91 Here he described his friendship with Ingres as “one of the luckiest encounters” of his life.92 Ingres possessed an unrivaled knowledge of Rome’s art treasures. “His glowing words gave new life to all those masterpieces,” wrote Liszt. “His eloquence transported us to bygone centuries.”93 Liszt even went so far as to describe Ingres’s explanations of art as intellectual masterpieces in their own right: “It was the genius of modern times evoking the genius of antiquity.”94 In Rome, Liszt finally found the intellectual community he had been seeking—it was rooted in the city’s culture and expatriate artists. As Liszt explained to Berlioz, Ingres strengthened his desire to increase his understanding of art, and in so doing broadened his exploration of the Republic of the Imagination:

The beauty in this special land became evident to me in its purest and most sublime form. Art in all its splendor disclosed itself to my eyes. It revealed its universality and unity to me. Day by day my feelings and thoughts gave me deeper insight into the hidden relationship that unites all works of genius. Raphael and Michelangelo increased my understanding of Mozart and Beethoven; Giovanni Pisano, Fra Beato, and Il Francia explained Allegri, Marcello, and Palestrina to me. Titian and Rossini appeared to me like twin stars shining with the same light. The Colosseum and the Campo Santo are not as foreign as one thinks to the Eroica Symphony and the Requiem. Dante has found his pictorial expression in Orcagna and Michelangelo, and someday perhaps he will find his musical expression in the Beethoven of the future.95

Was Liszt thinking of himself when he referred to the “Beethoven of the future”? I would wager yes, because a few weeks later he described his personal artistic goals to d’Agoult in less ambiguous prose: “Maybe I am a would-be genius; that is something that only time can tell…. My mission, as I see it, is to be the first to introduce poetry into the music of the piano with some degree of style.”96

Ideas such as this were likely the impetus behind Liszt’s setting of three Petrarch sonnets (nos. 47, 104, and 123) in 1839. He first set the sonnets as songs for high tenor voice, then transcribed them for piano shortly thereafter.97 Together, the three sonnets describe the various states of artistic inspiration and emotional turmoil brought on by Petrarch’s contemplation of woman sublime, the chaste, unattainable Laura. Sonnet 47 begins with a description of the exact moment when “two bright eyes” enthralled the poet’s soul and bound him fast. The final six lines then praise the inspiration that grew out of this encounter: “Blest be those sonnets, sources of my fame; / And blest that thought—Oh! Never to remove! / Which turns to her alone, from her alone which came.”98 Sonnet 104 reveals how contemplation of the ideal can release a range of desolate emotions: “I feed on grief, I laugh with sob-racked breast / And death and life alike to me are bleak: / My Lady, thus I am because of you.”99 Finally, in Sonnet 123, the vision of woman sublime returns to soothe the poet’s desire for inspiration: “I saw angelic grace in earthly spheres, / And heavenly beauty paralleled of none, / Which now I joy and grieve to think upon, / Since now all else dream, shadow, smoke appears.”100

Liszt included his heavily revised piano transcriptions of the above three sonnets in Années de pèlerinage, and I propose that they are among his earliest attempts “to introduce poetry into the music of the piano with some degree of style.”101 These pieces are not love songs as much as they are Liszt’s musical commentary on Petrarch. Liszt presents Petrarch’s Laura as woman sublime—indeed, he even added her name to the song text of Sonnet 104, in case there was any doubt. Like Raphael’s Sposalizio and Saint Cecilia, she is a chaste, unobtainable figure who blesses the artist-poet with divine inspiration.102 This practice of evoking women from the past was nothing new. Liszt’s literary heroes, Byron, Lamartine, and Madame de Staël had each done the same in the works they wrote about Italy.103 Aesthetic commentary via works of art was a common practice in Liszt’s Republic of the Imagination, and this is perhaps most evident in the final piece of year two of his Années de pèlerinage, “Après une lecture du Dante (Fantasia quasi Sonata).”

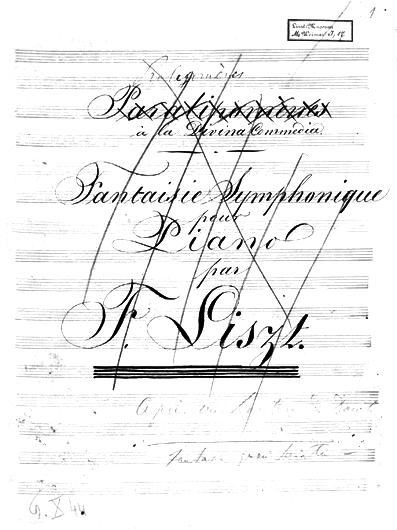

Although Liszt showed an interest in Dante’s Divine Comedy as early as 1832, it appears he waited until February 1839 to begin writing music inspired by the work.104 Liszt never published a program for this piece, but a look at the evolution of its title reveals much about his compositional approach. He first referred to the music in February 1839 as “a Fragment dantesque,” and it was premiered under this title in December at a concert in Vienna.105 Liszt considered publishing the composition in 1840, but these plans never came to fruition. By 1849, he was working on the piece again. The earliest extant manuscript source dates from this period and bears the title “Paralipomènes à la Divina Commedia: Fantasie Symphonique pour Piano” (figure 6). The term “Paralipomènes” refers to supplementary items originally omitted from the body of a work. Thus Liszt was composing a piece that expanded upon Dante’s Divine Comedy, much in the way that Byron had done in the Prophesy of Dante (1821).106 Sometime later, Liszt crossed out “paralipomènes” and replaced it with the word prolegomènes (preliminary discourses). This title, like the previous one, implies that Liszt was conceiving of his work as a commentary. Finally, around 1853, Liszt settled on the title we know today: “Après une lecture du Dante (Fantasia quasi Sonata).” The first half of the title is a subtle reference to a poem by Victor Hugo; the second half is an allusion to the genre title adopted by Beethoven for his two piano sonatas, op. 27.

The poem by Victor Hugo, titled “Après une lecture de Dante” (after a reading of Dante), is a poetic commentary on Dante’s depiction of hell. It is part of a collection of fifty-one poems (many of which are commentaries on artists and poets, such as Dürer and Virgil) published under the title Les Voix intérieures (Interior voices). When Liszt published his musical commentary on Dante, titled “Après une lecture du Dante” (after a reading of the Dante, i.e., The Divine Comedy), he purposely referenced Hugo’s poem without citing it directly. Liszt wanted audiences to recognize that, like Hugo, he was offering them his personal response to Dante’s work. His musical commentary on Dante was one of his “voix intérieures”—a product of his travels across the Republic of the Imagination.

Figure 6. Franz Liszt, page showing various early titles for “Après une lecture du Dante (Fantasia quasi Sonata).” Weimar, Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv, MS I 17.

How did Liszt’s experiences in Italy influence his creation of the Années de pèlerinage? Ultimately, they provided him with a program—an artistic philosophy from which he could draw. Looking at the titles of the various movements in Deuxième Année: Italie of Années de pèlerinage, one quickly realizes that the community Liszt encountered in Italy, via literature and art, provided him with creative role models. With the help of Byron, Michelangelo, and Rosa Liszt found his identity as an artist. Like Childe Harold, he became a pilgrim in search of a homeland. Like Il penseroso, he sought a life of contemplation free from the politics of contemporary society. Raphael and Petrarch offered images of woman sublime. Dante served as an “interior voice,” the intellectual culmination of his travels.

Although Liszt titled the second album of his Années de pèlerinage “Italy,” the music more accurately reflects his Republic of the Imagination. Perhaps he realized this as well, for in 1859, one year after the publication of Années de pèlerinage, Deuxième Année: Italie, he released a “supplement” to the volume, which is notably different in character. It comprises three pieces based on contemporary folk songs and opera arias: “Gondoliera,” “Canzone,” and “Tarantella”; the supplement symbolizes the contemporary, “real-life” music Liszt encountered in Italy—opera arias by Rossini and folk songs sung by Cornelio, Liszt’s Venetian gondolier.107

Liszt added a third volume to his Années de pèlerinage in 1883, and it too included pieces inspired by Italy. But discussion of that music will have to wait. By the time the Troisième Année was published, much had changed: Liszt had become an abbé; Italy had become a unified nation; and a new community of intellectuals had taken up residence in his Republic of the Imagination.

1. The earliest accounts set Liszt’s travels in the context of a romance: Marie d’Agoult, Mémoires 1833–1854, ed. Daniel Ollivier (Paris: 1927); and Lina Ramann, Franz Liszt als Künstler und Mensch (Leipzig, 1880–94); Sharon Winklhofer, in “Liszt, Marie d’Agoult, and the ‘Dante’ Sonata,” 19th-Century Music 1 (1976): 15–32, follows this approach as well. Later writers have tended to describe Liszt’s journey in the context of a travelogue: Alan Walker, Franz Liszt: The Virtuoso Years 1811–1847 (Ithaca, N.Y.:1987, rev. ed.), pp. 244–84; Charles Suttoni, ed., An artist’s Journey: Franz Liszt (Chicago: 1989); and Luciano Chiappari’s series: Liszt a Firenze, Pisa e Lucca (Pisa: 1989); Liszt a Como e Milano (Pisa: 1997); Liszt francescano tra Umbria e Marche (Grottammare: 2000), or as a Bildungsroman: Cesare Simeone Motta, Liszt Viaggiatore Europeo: Il soggiorno svizzero e italiano di Franz Liszt e Marie d’Agoult (1835–39) (Moncalieri: 2000).

2. Chateaubriand’s “Lettre à Fontanes sur la campagne romaine,” dated 10 January 1804, was published in Mercure de France, 3 March 1804.

3. Dana Gooley, The Virtuoso Liszt (Cambridge, Eng.: 2004), pp. 22–23.

4. Wheelock Whitney, “Introduction,” in The Lure of Rome: Some Northern Artists in Italy in the Nineteenth Century, exhibition catalogue, Hazlitt, Gooden & Fox Gallery (London), October–November 1979, p. 7.

5. See especially Motta, whose primary thesis in Liszt Viaggiatore Europeo is that as Liszt and d’Agoult traveled across Italy, Liszt began to see his time there as a period of enlightenment typical of the Grand Tour experience.

6. Italy served as the inspirational push behind many of Liszt’s works—the tone poem Tasso, the incomplete opera Sarandapale, Totentanz, Réminiscences de la Scala, and Venezia e Napoli, for example, but none give as complete an overview of Liszt’s intellectual pursuits as Années de pèlerinage: Deuxième Année, Italie.

7. As Dolores Pesce, “Expressive Resonance in Liszt’s Piano Music,” in Nineteenth-Century Piano Music, ed. R. Larry Todd (New York: 1990), pp. 358–59, explains, the contents of this volume “relate at least in part to an earlier collection that appeared in 1842, the Album d’un Voyager (Album of a traveler),” which Liszt began writing during a trip to Switzerland in 1835–36. “The Album consists of three parts: Impressions and poésies, seven titled pieces that became the core of Année 1; Fleurs mélodiques des Alpes, nine untitled pieces based on Swiss folk songs or popular art songs (two reappearing in Année 1); and Paraphrases, three arrangements of Swiss folk airs.” It should be noted that if Liszt withdrew this publication before publishing Années de pèlerinage, one reason may be that in its revised version, this set of pieces inspired by Switzerland presented a markedly different program.

8. Many have mistakenly claimed that as Liszt traveled across Italy, he followed the path previously laid out by Goethe. Although it is true that Liszt visited many of the same locales, he did not follow his predecessor’s itinerary.

9. Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Julian and Maddalo” in Posthumous Poems (London: 1824), lines 55–57: “How beautiful is sunset, when the glow / Of Heaven descends upon a land like thee, / Thou Paradise of exiles, Italy!” For discussions of this period in Italy’s history, see Christopher Duggan, A Concise History of Italy (Cambridge, Eng.: 1994). For discussions of the effects of Italian politics on nineteenth-century English literature, see Maura O’Connor, The Romance of Italy and the English Political Imagination (London: 1998); Daryl S. Ogden, “Byron, Italy, and the Poetics of Liberal Imperialism,” Keats-Shelley Journal 49 (2000): 114–38.

10. Franz Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, ed. Rainer Kleinertz (Wiesbaden: 2000), vol. 1, pp. 455–503.

11. Charles Suttoni, An artist’s Journey (Chicago: 1989), p. 244. For the most recent discussion of this topic, see Alan Walker, “Liszt the Writer: On Music and Musicians,” Reflections on Liszt (Ithaca, N.Y.: 2005), pp. 217–38. In truth, the authorship of these articles is of little consequence to my investigation, since, despite their origins, they nonetheless present a reliable description of Liszt’s reactions to art and literature as he traveled through Italy.

12. See especially Pesce, “Expressive Resonance in Liszt’s Piano Music,” b355–75; Andrew J. Fowler, “Franz Liszt’s Années de pèlerinage as megacycle,” Journal of the American Liszt Society 40 (1996): 113–29; William J. Hughes, Jr. “Liszt’s Première Année de Pèlerinage: Suisse: A Comparative Study of Early and Revised Versions,” D.M.A. diss., Eastman School of Music, 1985; Karen Wilson, “A Historical Study and Stylistic Analysis of Franz Liszt’s Années de pèlerinage,” Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina, 1977, and Martin Zenck, “Die Poetik und Struktur in Franz Liszt’s Tondichtung Après une lecture du Dante im Zusammenhang der ‘Correspondance de Liszt et de la Comtesse d’Agoult,’” in Musik und Szene: Festschrift für Werner Braun zum 75. Geburtstag (Saarbrücken: 2001), pp. 575–95.

13. George Sand, “Lettre d’un Voyageur,” Revue des deux mondes, 1 September 1835. Another source for my use of the phrase “Republic of the Imagination” comes from the title of an article by Azar Nafisi that appeared in the Book World section of the Washington Post on 5 December 2004. In this article, Nafisi defines her own encounters with the Republic of the Imagination—her private escape, via masterpieces of Western literature, from the political and intellectual oppression of life in Iran. I had the pleasure of discussing the Republic of the Imagination with Dr. Nafisi on several occasions at the American Academy in Rome in Summer 2005, and I am sincerely grateful for her insight into the topic.

14. I thank Dana Gooley and Christopher Gibbs for the various discussions we had concerning the politically charged atmosphere Liszt experienced in Paris. Liszt was a supporter of the 1830 revolution in France, which alas brought a monarchy. A significant line of thought about Romanticism claims that when its participants became disillusioned by political failures such as the 1830 French revolution, they waged their own philosophical battles in the realm of fantasy. This is an apt description that can be applied to both Sand and Liszt.

15. For a daily account of Liszt’s tour through Switzerland, see Mária P. Eckhardt, “Diary of a Wayfarer: The Wanderings of Franz Liszt and Marie d’Agoult in Switzerland June–July 1835,” Journal of the American Liszt Society 11 (June 1982): 11–17; and 12 (December 1982): 182–83.

16. Sand, “Lettre d’un Voyageur.”

17. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 78; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, pp. 4–5.

18. Ménestrel 3, no. 15 (13 March 1836). As Dana Gooley explains in The Virtuoso Liszt, “Three aspects of Thalberg’s reception were particularly troublesome for Liszt.” First, the praise from Parisian audiences was unanimous for Thalberg, but not for Liszt. Second, Thalberg was revered even though he “was not in any sense a literary or philosophical artiste,” which was the way that Liszt wanted to be envisioned. Third, Thalberg was praised for his talents as a composer in addition to his abilities as a performer, something that Liszt could not yet claim (pp. 23–24).

19. Gooley, The Virtuoso Liszt, p. 27.

20. Berlioz was also distressed by Liszt’s attack on Thalberg; he was acting editor of the Revue et Gazette musicale de Paris when Liszt submitted the review, and he added a notice to the article dissociating the journal from Liszt’s personal opinions.

21. Revue et Gazette musicale, 12 February 1836.

22. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 90; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, pp. 14–15. The final line is a reference to Mignon’s song from Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister: “Kennst du das Land, wo die Zitronen blühn?…Dahin! Dahin! Möcht’ ich mit dir, o mein Geliebter, ziehn.” (Do you know the land, where the lemons bloom?…There! There! Do I wish to move, with you, o my beloved.)

23. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 100; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, pp. 28–29.

24. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 104; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, pp. 30–31.

25. Gooley, The Virtuoso Liszt, p. 19.

26. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 108; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, pp. 34–35.

27. For an excellent overview of the French Academy at this time see the exhibition catalogue Maestà di Roma da Napoleone all’unità d’Italia: Da Ingres a Degas: Artisti francesi a Roma (Rome, 7 March–29 June 2003).

28. Liszt described this desire for artistic interaction in rather poetic terms: “Somewhere, far away in a land that I know, there is a limpid spring that lovingly bathes the roots of a lone palm tree. The palm tree raises its fronds above the spring, sheltering it from the sun’s rays. I want to rest in that shade—a touching symbol of the holy and indestructible affection that supplants all earthly concerns and will doubtless flourish in heaven.” Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 112; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, p. 38.

29. Revue et Gazette musicale, 11 February 1838. Liszt first met Adolphe Pictet de Rochemont (1799–1875) during his first trip to Geneva. On that occasion, Pictet accompanied Liszt, d’Agoult, and Sand on a trip to Chamonix. Pictet published an account of this trip in Une Course à Chamonix (Paris: 1838). Liszt’s queries are strikingly familiar with those found in Letter 53 of Senancour’s Obermann.

30. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, pp. 114–18; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, pp. 41–45.

31. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 122; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, p. 47. Liszt is referring to a passage he read in Blaise Pascal’s Pensées (1660). H. F. Stewart, editor of Pascal’s Pensées (London: 1950), p. 504, claims that Pascal got this idea from Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (1627–1704).

32. Revue et Gazette musicale, 25 March 1838. Louis de Ronchaud (1816–87) was a young writer, later an art historian, whom Liszt and d’Agoult met in Geneva. In later years, he became d’Agoult’s literary executor, and he edited her posthumous Mes Souvenirs 1806–1833 (Paris: 1877).

33. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 133; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, pp. 56–57.

34. Robert Hollander, “Dante and His Commentators,” in The Cambridge Companion to Dante, ed. Rachel Jacoff (Cambridge, Eng.: 1993), p. 232.

35. “Lake Como—To Louis de Ronchaud” Revue et Gazette musicale (22 July 1838). Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 162; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, p. 67. Sharon Winklhofer, “Liszt, Marie d’Agoult, and the ‘Dante’ Sonata,” attributes this passage to d’Agoult alone, claiming that Liszt showed little interest in Dante at this time (p. 24), but she gives no evidence to support this assumption.

36. This description of women also explains why Liszt often referred to Sand as “he” instead of “she” in his personal correspondence and articles.

37. In her article “Liszt, Marie d’Agoult, and the ‘Dante’ Sonata,” Winklhofer successfully destroyed the myth Lina Ramann perpetuated concerning the origins of Liszt’s “Dante” Sonata. But she also started a new myth by asserting that Dante provided Liszt with “a model for his relationship with Marie d’Agoult” and that as “the Dante-Beatrice roles proved impossible to uphold” Liszt’s concept of Dante changed. There is no direct evidence that Liszt ever looked to d’Agoult as his Beatrice—all the sources presented by Winklhofer came from d’Agoult’s memoires. I propose that it was d’Agoult who looked to Beatrice and Dante as the paradigm for her relationship with Liszt. This appears to be the way Liszt himself saw the situation. As Walker explains in Franz Liszt: The Virtuoso Years, after their breakup, it was Marie who kept referring to the Beatrice-Dante model. Liszt was noticeably less enamored with this model: “Bah, Dante! Bah, Beatrice! The Dantes create the Beatrices, and the real ones die at eighteen!” (p. 246).

38. Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, p. 83. Liszt often performed at these soirees. As Suttoni mentions, Liszt and the tenor Adolphe Nourrit performed at Rossini’s with great success on 12 January 1838 (p. 72).

39. The plate numbers for these works are 2116 for the tenor and chorus version and 9115 for the piano transcription. I thank Francesco Izzo for assisting me in tracking down the publication dates for these works. Although they are difficult to come by today, they would have been readily available to Liszt when he was in Milan. A copy of the piano transcription, which originally belonged to Gelasii Caietani, can now be found in the Vatican Library (Racc. Gen. Musica. II 262 [int. 1–6]). The Rossini piece is bound together with a collection of piano transcriptions dating from the same period. Curiously, the back cover of the Rossini transcription contains a pencil sketch of a woman (in typical 1830s Italian fashion) and a man in profile whose appearance is strikingly similar to that of Rossini.

40. “La Scala: To Maurice Schlesinger,” Revue et Gazette musicale, 27 May 1838: “Everything in the sphere of art corresponding to the feelings immortally exemplified by Hamlet, Faust, Childe Harold, René, Obermann, and Lélia is for the Italians a foreign, barbaric tongue that they reject in horror…. Rossini, that great master who possessed a fully strung lyre, scarcely sounded anything but the melodic string for them. He treated them like spoiled children, entertaining them as they wanted to be entertained.” Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 158; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, pp. 76–77. Liszt also paid homage to Rossini at this time by transcribing for piano solo his William Tell Overture and a collection of his songs and duets entitled Soirées musicales.

41. In a later article about Milan (“To Lambert Massart”) that appeared in the Revue et Gazette musicale on 2 September 1838, Liszt mentioned “Madame de Staël’s definition that ‘music is the architecture of sounds.’” Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 185; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, p. 90.

42. Elizabeth Way, “Raphael as a Musical Model: Liszt’s ‘Sposalizio’,” Journal of the American Liszt Society 40 (1996): pp. 103–12; and Joan Backus, “Liszt’s ‘Sposalizio’“: A Study in Musical Perspective,” 19th-Century Music 12, no. 2 (1988): 173–83, propose that Raphael’s Sposalizio and the Liszt piece share similar compositional designs.

43. Marie d’Agoult, Mémoires 1833–1854, (Paris: 1927), p. 131.

44. “To Heinrich Heine,” Revue et Gazette musicale, 8 July 1838; Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 176; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, p. 106. The article begins with a quote from Canto IV of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: “I stood in Venice, on the Bridge of Sighs.” And sigh Liszt most certainly did as he responded to what he believed to be a gratuitous attack from a close friend and colleague. In particular, Liszt was troubled by Heine’s accusation that he was “unsettled” philosophically. Much like Byron, Liszt prefaced the description of Venice with references to some of the city’s most famous landmarks and historic figures: the bronze horses of St. Mark’s—“the winged lion of St. Mark, still atop his African column and still gazing toward the sea”—and the medieval doges Enrico Dandolo (d. 1205) and Marino Faliero (ca. 1278–1355). Faliero, a corrupt commander of the Venetian forces who was elected doge in 1354 and committed murder in an attempt to become prince, was an especially popular literary character at the time. Both Byron and Dasimir Delavigne made him the subject of tragedies. He was also the central character in a tale by E. T. A. Hoffmann and an opera by Donizetti that premiered in 1835.

45. Liszt remained in Vienna 10 April–26 May. For a detailed description of this trip see the chapter by Christopher Gibbs, “Just Two Words. Enormous Success,” included in this volume. Press reports of Liszt’s Vienna concerts are given in Dezsö Legány, Franz Liszt: Unbekannte Presse und Briefe aus Wien 1822–1886 (Budapest: 1984), pp. 22–58.

46. Liszt mentioned this article in a letter to his mother in late July 1838: “Tell Massart that I have written a letter addressed to him for the Revue et Gazette musicale. He will have it very soon.” Liszt, Briefe an seine Mutter, ed. La Mara (Leipzig: 1918), pp. 48–49. In his collection of Liszt’s articles, Suttoni separates the two parts of this letter and inserts the article “To Heinrich Heine” between them, since part I discusses “Milan” and part II discusses “Venice.” This might seem practical in terms of creating a chronological travelogue of Liszt’s time in Italy, but it completely destroys the “before-and-after effect” that I think Liszt was intending to present in this article.

47. Julia Pahlen-Samoyloff (1803–1875), a Russian noblewoman living in Milan, hosted numerous music soirées. Liszt became good friends with her during his time in Milan, and he dedicated the Ricordi edition of his (Rossini) Soirées musicales to her.

48. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 190; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, p. 95. Suttoni claims that this dream sequence is a reference to Heine, but it is clearly connected to Liszt’s reading of Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.

49. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 192; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, pp. 95–96.

50. Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Canto I, II. 46–54, p. 24.

51. Ibid., II. 109–17.

52. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 194; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, p. 97.

53. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 194; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, p. 98.

54. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 196; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, p. 139.

55. Liszt, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1, p. 204; Suttoni, An artist’s Journey, p. 144.

56. On 26 November 1838 d’Agoult wrote to Adolphe Pictet that she and Liszt were visiting the Medici Chapel often in order to study Michelangelo’s statues. Robert Bory, Une Retraite romantique en Suisse: Liszt et la Comtesse d’Agoult (Lucerne: 1930), pp. 148–49.

57. Lorenzo de’ Medici, duke of Urbino, ruled Florence from 1513 until his untimely death in 1519. He was an avid patron of arts and letters and the dedicatee of Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince (1515).

58. The bat serves as the emblematic animal in Dürer’s famous engraving, Melancholia I.

59. Erwin Panofsky, Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance (New York: 1939), p. 180. Since the appearance of Panofsky’s work on Michelangelo, some scholars have challenged his ideas, claiming that artists such as Michelangelo would not have drawn on philosophical sources to such a great degree. For a comprehensive look at the reception of Panofsky’s work in the last half-century, see Carl Landauer, “Erwin Panofsky and the Renascence of the Renaissance,” Renaissance Quarterly 47, no. 2 (1994): 255ff.

60. Panofsky, Studies in Iconology, p. 209.

61. The Poetry of Michelangelo: An Annotated Translation, trans. J. Saslow (New Haven, Conn.: 1991), p. 419. For the original Italian, see Michelangelo Buonarroti, Rime (Milan: 1975).

62. According to Rena Mueller, in “Liszt’s ‘Tasso’ Sketchbook: Studies in Sources and Revision,” Ph.D diss., New York University, 1986, there are two citations on pages 19 and 20 in Liszt’s Poetisches Album (Weimar: Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv, MS 142) labeled “Strozzi’s Inschrift zur Michel Angelos Nacht” and “Michel Angelos Antwort” which date from the 1840s (pp. 157–58).

63. It should be noted that in the 1860s Liszt composed a work called “La Notte,” which is an expanded version (with additional Hungarian material) of “Il Penseroso.”

64. Rosa was the primary character in “Signor Formica,” a short story by E. T. A Hoffmann. Berlioz’s librettists Wailly and Barbier incorporated elements of this story into the carnival scene in Benvenuto Cellini. Rosa also made an appearance, albeit fictive, in chapter 30 of Le Corricolo by Alexander Dumas, père. For a detailed study of Rosa’s reception in France, see James S. Patty, Salvator Rosa in French Literature: From the Bizarre to the Sublime (Lexington, Ky.: 2005). For information concerning the publication of Hoffmann’s “Signor Formica” in the Revue et Gazette musicale see: James Haar, “The Conte Musical and Early Music,” in La Renaissance et sa musique au XIXe siècle, ed. Philippe Vendrix (Tours: 2004), p. 187; and Katherine Ellis, Music Criticism in Nineteenth-Century France: Revue et Gazette musicale de Paris 1834–1880 (Cambridge, Eng.: 1995), App. 3.

65. Helen Langdon, “Salvator Rosa,” Grove Dictionary of Art, ed. Jane Turner (London: 1996).

66. Lady (Sydney) Morgan, The Life and Times of Salvator Rosa, 2 vols. (London: 1824).

67. As Margaret Murata, “Dr. Burney Bought a Music Book,” Journal of Musicology 17, no. 1 (1999): 82, explains: “Musical notation in Rosa’s hand can be seen in two paintings attributed to him,” one of which Liszt might have seen in Italy: “an allegorical representation of La Musica” that “holds a texted vocal part (Rome: Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica).” In addition, Michael Mahoney, The Drawings of Salvator Rosa, 2 vols. (New York: 1977), notes at least three drawings preserved on sheets of lined music paper (vol. 1, p. 289).