In a century when particularist national identities increasingly dominated music’s public spheres, Franz Liszt moved with ease between nations and social movements: the Christian Socialism of the Saint-Simonians in France, a flourishing Hungarian nationalism, the “New German” avant-garde of Weimar and Bayreuth. Simply put, the generic breadth of Liszt’s music and the wide range of his friendships, posts, and tours across the continent encapsulate an ideal of European cosmopolitanism unmatched by his musical peers. But Liszt’s fluency in navigating the rough waters of nineteenth-century nationalism also brings to mind his virtuosity more generally. And for the most part, we have come to view Liszt’s continental peregrinations and his support of multiple national projects solely through the lens of his career as a traveling virtuoso and pedagogue, or as a reflection of his out-sized and seemingly adaptable persona. So conceived, nations and national publics figure primarily as easy referents of theatrical gesture (such as Liszt’s “Hungarian” costume, donned after the 1838 floods) or as anonymous, hapless participants in a nascent mass culture nurtured by the “virtuoso public sphere.”1 In the schemata of Liszt’s conquering virtuosity, Europe’s peoples function all too easily as willing dupes in a cynical attempt to extract disposable identities—as well as cash—from audiences and the public spheres they have come to represent.2

Yet Liszt’s engagement with Europe’s national publics extended well beyond costumes and cadenzas. Although the question of opportunism may never entirely cease to haunt his cosmopolitan enthusiasms—cynical intent is impossible to disprove—recent considerations of Liszt’s virtuosity have begun to complicate this charge by emphasizing the careful negotiations between Liszt and his many audiences.3 Moreover, the myriad national projects to which Liszt contributed shared a number of lateral connections. Both Liszt’s cosmopolitanism as well as the nations it served were underwritten by a constellation of ideals—populism, collective sovereignty, and the increasingly interchangeable liturgies of church, nation, and art—whose convergence marks the cultural and political landscape of Europe in the nineteenth century. And in this sense, it was neither particularly difficult nor inconsistent for Liszt to have supported, and even adopted, multiple nationalities across the continent; there is perhaps no better evidence to support Carl Dahlhaus’s supposition that nineteenth-century nationalist composition “was seen as a means, not a hindrance, to universality.”4

Nowhere is this clearer than in the case of Liszt’s choral music, where the promotion of a noble communal subject frequently underlies a variety of works spanning nations, genres, and political persuasions. To be sure, the corporate body at the heart of the choral music remains an abstraction; it is an “imagined community,” a heady rhetorical construct borne more of high-minded idealism than any sustained engagement with the “real” peoples the works claim to envoice.5 And as Paul Merrick has shown, much of Liszt’s choral music stems from many of the same political, aesthetic, and religious convictions that informed those piano and symphonic works better known to us today; it would thus be a mistake to portray the choral compositions simply as good-natured community service written in penance for an otherwise high-flying solo career.6 But a consideration of Liszt’s choral music suggests that his commitment to the many social, political, and religious movements of the nineteenth century is a good deal more complicated than the sheer opportunism imputed to his virtuoso persona. Many of Liszt’s choral works evince a kind of communal magnanimity—that is, a figurative attempt to employ “the people” as guiding muse and participants rather than audience alone—that has not always figured prominently in the reception of his virtuosity. Crucially, however, these choral compositions also betray an ambivalence as to the limits of that magnanimity.

This essay explores some of these complexities by focusing on Liszt’s “Beethoven” cantatas of 1845 and 1870–two works that place front and center how a communal voice might be simultaneously national and universal, how the figure of the collective is to be reconciled with that of the singular artist, and how the burden of genres and musics past may be balanced with the onus of musical progress. In other words, the cantatas render in choral form several tensions marking Liszt’s controversial career and nineteenth-century musical culture more generally. And although both compositions are largely forgotten today, they figured prominently in Liszt’s compositional career. The 1845 cantata was his first work for mixed chorus and orchestra, and its performance at the unveiling of Bonn’s Beethoven statue cemented Liszt’s place among a cosmopolitan public of Beethoven admirers. By contrast, the 1870 cantata was one of Liszt’s final compositions for chorus and orchestra. It was written for Weimar’s centenary celebration of Beethoven’s birth, as well as for that year’s meeting of the Allgemeine Deutsche Musikverein—a joint provenance that, as we will see, marks not only the nationalization but also the political manipulation of Beethoven’s memory in service of a “New German” teleology of musical history. Negotiating these questions of nationality, progress, and the politics of memory is the chorus lying at the heart of both cantatas. Its varied treatment in the two works illuminates both the promise and the limitations of collective sovereignty in Liszt’s aesthetics and indeed the larger musical world.

Liszt traced his lifelong interest in choral music back to an 1825 visit to London, in which he was impressed by the massed children’s choirs and St. Paul’s Cathedral.7 But although a noble seriousness underlies most of Liszt’s compositions for chorus, it was only in the latter half of the century that he regularly began to write explicitly religious music. Many of his first choral compositions, much under the influence of Lamennais and the Saint-Simonians, were political in nature.8 In addition to his advocacy of the German nationalist movement in “Das deutsche Vaterland” and the “Rheinweinlied” of the early 1840s, Liszt’s choral works from the end of the decade illustrate a continued concern for political causes across Europe.9 Chief among these later compositions is a triumvirate of Männerchor works from the late 1840s—Le Forgeron, Hungaria 1848, and an Arbeiterchor—stemming from Liszt’s support of the workers’ and Hungarian nationalist movements.10 But Liszt’s work, along with that of most European artists and thinkers, became less overtly political in the years following the failed 1848 revolutions. The 1850s witnessed sustained efforts at both large- and small-scale religious compositions, as well as secular occasional works stemming from his time in Weimar, such as choruses for the 1850 Herder festival.

His first large-scale religious work was the Missa Solennis of 1855, composed for the consecration of the cathedral in Gran. After several years’ time concentrating mainly on the symphonic poems, Liszt announced his desire to “solve the oratorio problem”; the first of these compositions, finished in 1862, is Die Legende von der heiligen Elisabeth.11 The work is built on chant melodies bearing a connection to Elisabeth (such as the hymn “In festo, sanctae Elisabeth”), Hungarian folk song and rhythms, and Liszt’s telltale “cross” motive of a minor third enclosed within a perfect fourth. Given its penchant for harmonic and dramatic effect, the oratorio comes as close as any of Liszt’s works to his premise that the “religious music of the future” must unite the theater and the church.12 (The Christus oratorio of 1866–72 comes close, however, as does the Missa Solennis—so much so that Hanslick complained that Liszt had “brought the Venusburg into the church.”)13 In fact, the Elisabeth oratorio was staged during Liszt’s lifetime—albeit without his blessing—and its operatic performance became something of a cause célèbre among Wagnerian circles, Hans von Bülow having designated it a “spiritual drama.”14 But following Christus and the second “Beethoven” cantata, Liszt tended to eschew these works’ lengthy forms and large performing forces. The intimate sacred compositions of his last decade, such as Via Crucis of 1878–79, have an intensity of both religious fervor—Liszt called it an “inner necessity of a Catholic heart”—and harmonic daring.15 Hence Ossa Arida from 1879, for unison men’s voices and organ with two players, has become a perennial favorite among biographers and analysts alike due to the radical conglomeration of thirds with which it begins.

As this short sketch of Liszt’s choral works suggests, there is a general movement from the more explicitly political and secular works in the earlier stages of his compositional career toward the religious, and musically more ambitious, works of his middle and later years. Of course, such a scheme remains just that; the line between secular and sacred is often ambiguous at best, “high art” music in general grew increasingly complex in its formal and harmonic vocabularies throughout the century, and the changing political scene following both the 1848 revolutions and the Franco-Prussian War inevitably influenced the social contexts of choral music more generally. Yet these broader developments should not be seen as external elements that a consideration of Liszt’s choral music must factor out; rather, they are the very preconditions of these works. As the political, religious, and musical landscapes shifted in the nineteenth century, so too did Liszt’s contributions to the choral movement.

Liszt’s choral music must also be understood within the institutional context of the choral societies, for it is here, in the cultural and political world of associational life, that choral music most explicitly participated in the public sphere of European nationality. In Germany in particular, liberalism, democracy, and nationalism all found fertile ground in these primarily bourgeois institutions seeking to exercise cultural and political autonomy.16 Moreover, it was in the network of associations that the push for German unification found some of its most vociferous support among bourgeois liberals.17 As the institutional locus for political movements claiming to represent “the people” rather than the church or particularist states, associations such as choral societies sought legitimization in what has become the highly overdetermined category of das Volk.18 In line with the edifying promises accorded choral singing as well as associational life more generally, bourgeois intellectuals utilized the notion of the Volk as both the subject and object of their ennobling enterprise: that is, they argued that their associations were already constituted by the Volk and simultaneously functioned as disciplinary role models for an inchoate, ever-emerging Volk.19 At once a rhetorically beneficial subject position and a distant object in need of ennobling pedagogy, the category of das Volk provided useful cover for a bourgeoisie whose high-minded claims to homespun indigeneity also kept at arm’s length the more radical populism its liberal ideals spawned, but rarely embraced (universal suffrage, for instance, was not part of the liberal platform).20

Liszt’s own choral aesthetics reflect this ambivalence. Indeed, the changing fortune of an imagined Volk—the extent to which the choral collective is accorded the figurative status as autonomous generating subject or dependent impoverished object in the exchange of religious, musical, or national sentiments—constitutes a central axis along which Liszt’s choral music can be organized. His written formulation of the matter comes in the essay “On the Situation of Artists” (1835), in the section on “religious music of the future.” Here, as John Williamson has pointed out, the influences of both Lamennais and the Saint-Simonians join forces to promote a model of religious song modeled after the songs of the people (such as the “Marseillaise”).21 Such music will be “patriotic, moral, political, and religious in nature…written for the people, taught to the people, and sung by the people.” Yet this music is not from the people. In a clever modification of the dictum vox populi vox dei, Liszt retains both God and Volk, but the latter now serves as muse rather than author: “Come, O hour of deliverance, when poets and musicians, forgetting the ‘public,’ will only know one motto, ‘The people and God.’”22 The “religious music of the future” will ultimately stem from the genius, the artist-priest. The extent of this mediation, the tipping point between an avant-garde prophet’s supervisory role and the collective’s push for sovereign subjecthood, is a central animating tension in Liszt’s contributions to the choral movement. And as the “Beethoven” cantatas make clear, this tension is amplified by both the musical conflict pitting the chorus’s generic past against the progressive thrust of Liszt’s Zukunftsmusik, as well as the societal implications of investing the chorus with its most idealistic utopian visions.

Although both cantatas quote extensively from the slow movement of Beethoven’s “Archduke” Trio, op. 97, the Weimar work is not an updated version of the Bonn one, as Alan Walker has claimed.23 The cantatas could hardly be more different: between them lie twenty-five years of Liszt’s development as a composer, Beethoven’s posthumous memorialization, and, most significant, the hardening boundaries between a communal voice issuing from below—understood as the collective recipients of Beethoven’s legacy—and an increasingly authorial voice legislating from above. Indeed, it would not be a stretch to claim that the two works are differentiated by the revolutionary promise of the Vormärz and the straightened politics of Bismarck’s new Germany, an era less immediately receptive to an earlier ideal of collective agency.24 Who would claim Beethoven’s legacy, how the music of the future would accommodate that of the past, and the respective roles that the artist-genius and the chorus-of-Volk would play in this musicosocial transformation are guiding themes of the two cantatas.

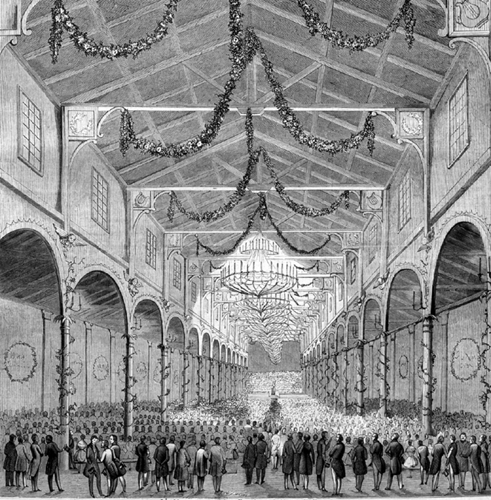

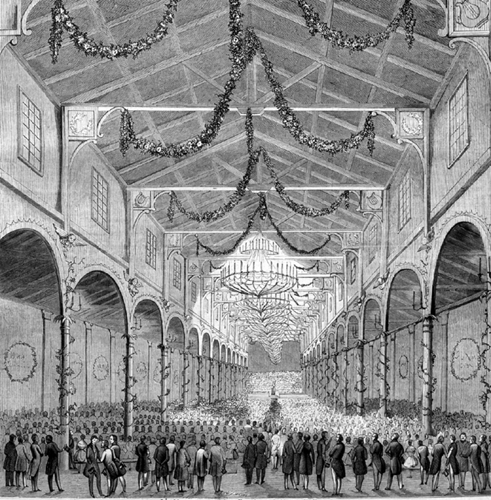

From the start, Liszt’s multifaceted involvement with the Beethoven monument—as financial donor, composer, conductor, and resident virtuoso—attracted no small amount of publicity. He not only paid for the festival’s hastily built concert hall (figure 1); he also featured prominently in two of the three concerts that made up the celebrations (figure 2). One newspaper quipped that it was a “Beethoven festival in honor of Liszt,” and this view of both the 1845 festival and Liszt’s cantata for it has remained intact by less sympathetic critics to this day.25 The cantata has recently been portrayed by Alexander Rehding, for instance, as a kind of self-promoting monumentalism. But while the work’s monumental aspirations are undeniable, it is less clear that the cantata represents Liszt as the sole recipient of those aspirations. Rehding’s contention that the cantata served only to promote Liszt, to “consolidate his reputation as the chosen heir” and “instrumentaliz[e] Beethoven to further his own immortality,” downplays the text of Liszt’s cantata, which explicitly promotes the collective as Beethoven’s immortal heir. And his reading of the cantata is also complicated by the other occasional works written for the festival, all of which emphasize a similar communal subject as guardians and recipients of Beethoven’s timeless music.26 Put quite simply, the “self” in Liszt’s “self-promotion” is not Liszt alone, but Liszt among—and for—many.

As Liszt saw it, the cantata’s text (written by the Jena poet and professor Bernhard Wolff) “is a sort of Magnificat of human genius conquered by God in the eternal revelation through time and space—a text which might apply equally well to Goethe or Raphael or Columbus as to Beethoven.”27 With Beethoven as such absent from most of the cantata, the role of protagonist is taken on by the chorus of the Völker (see excerpts from the text, below). In Wolff’s text, the Völker are caught in the currents of time, destined to perish because they never achieve permanence in the “book of world history.” A prince may represent the people in a historical sense, but the Volk searches for someone among its ranks that can tell of its suffering, its aspirations, and its humanity to later generations. It is the genius, sent from the Volk but crowned by God, who lends those on earth “the reflection of brightest eternity.” Beethoven is celebrated as such a genius, and the cantata ends with repeated Heils to the composer.

Figure 1. The “Artists’ Concert” where the Bonn cantata was performed.

Figure 2. Program for the Bonn musical festivities.

Excerpts from the Bonn Cantata’s Text

| I | |

| Kommt und bringet euer Bestes, kommt, ihr Hohen und ihr Niedern mit den reichsten, schönsten Liedern. Heut ist wahrhaft ein Tag des Festes | Come and give of your best, come, high-born and lowly, with the richest, most beautiful songs, |

| today is truly a day of festivity. | |

| Es ist der Weihetag der Genius! | It is the day consecrated to genius. |

| II | |

| Gleich den Wogen des Meeres rauschen die Völker alle vorüber im Zeitenstrom. | Like sea waves, all peoples rush by in the river of time. |

| Heute kommt, was morgen fleucht, heute wirkt, was morgen stirbt, für den Untergang erzeugt, nimmer Dauer sich erwirbt. | What comes today is gone tomorrow, what is effective today dies tomorrow, doomed to its decline, never gaining permanence. |

| III | |

| Die Völker, die vorüberzogen, versanken in die Nacht der Nächte: nur ihrer Herrscher Namen geben Kunde von ihrem Tun dem späteren Geschlechte. | The peoples who passed by sank into the night of nights: only the names of their rulers tell later generations of their deeds. |

| In dem Buch der Weltgeschichte…tritt der Fürst ein für sein Land. | In the book of world history…the ruler speaks for his country. |

| Aber soll der Menschheit Streben Auch entfluten mit dem Leben? Wird denn Nichts den fernsten Jahren Was sie wirkt aufbewahren? | But should humanity’s ambitions also recede with its life? Will nothing of what it achieved be retained for posterity? |

| Arme Menschheit, schweres Los! Wer wird von dir entsendet an der Tage Schluss? Der Genius! In seinem Wirken ewig wahr und groß. | Poor humanity, heavy fate! Who from you will be sent at the end of time? The genius! Forever true and great in his effect. |

| IV | |

| Er…der Menschheit eint mit Gott…ist’s, der das Schicksal versöhnet. | He…who joins humanity with God…is the one who placates fate. |

| Heilig! heilig! heilig! Des Genius Walten auf Erden, er umhüllt das himmlische Werden, der Unsterblichkeit sicherstes Pfand. | Holy! holy! holy! The genius’s sway over earth envelopes heaven, the surest pledge of immortality. |

| Solch’ ein Fest hat uns verbunden! | Such a festival has united us! |

| Und es soll in fernsten Tagen noch sein Bild der Nachwelt sagen, wie die Mitwelt ihn verehrt. | And until the end of time his image will tell posterity that his contemporaries honored him. |

| Heil! Heil! Beethoven Heil! | Hail! Hail! Beethoven, hail! |

As Rehding points out, Wolff’s text seems surprisingly anti-royalist, given both the financial support by several royal houses and their physical presence at the festival. Especially in the Vormärz, an appeal to the Volk or Völker was not without political meaning, particularly in conjunction with a text that stressed a rupture between the Volk and its political representation.28 Yet the anti-royalist bent to Wolff’s text is also offset in several ways. For one, the Volk is never explicitly the Germanic Volk, and repeated references to Völker generalize the sentiments beyond any particular nation. Not unlike the Völker populating Beethoven’s Der glorreiche Augenblick of 1814, this is an essentially anonymous grouping of peoples that any of Europe’s nations could have formed. (Although Rehding notes that the liberal German national flag can be made out in illustrations of the Bonn festival.29) Notably, the chorus switches to second-person in those sections of the cantata that narrate the plight of the Völker—a change in poetic voice that distances the Bonn festivity and its performers from the freighted text. At the same time, however, the chorus claims at the cantata’s close that “this celebration has united us,” and this self-referentiality serves to reconnect the choral participants to the liberal narrative that forms the core of the cantata’s text.

Wolff’s use of a communal protagonist may seem odd in a text ostensibly about Beethoven, but it was by no means unusual; virtually all of the text’s sentiments were expressed on other occasions during the Bonn festivities. Indeed, an examination of the other festival texts reveals a consistent attempt, varying only in intensity, to articulate a collective subject as the beneficiary of Beethoven’s music, his perceived timelessness, and the Bonn festivity itself. Four works serve as useful points of comparison: a Festchor by H. K. Breidenstein, also written for the statue’s unveiling, with a text by Wilhelm Smets; two “festival greetings” for the arrival of Beethoven’s statue in Bonn on 23 July, written by E. M. Kneisel, secretary of the Bonn committee; and “Beethoven,” a festival poem written for the unveiling by Wolfgang Müller, a Rhenish doctor and future member of the 1848 Frankfurt parliament.30 (A drawing of the statue at the heart of the festivities is shown in figure 3.)

Just as Wolff employs imagery of redemption and the genius’s heavenly provenance (Beethoven is “crowned by God,” revealing his “immortality”), Müller’s poem refers to Beethoven as the savior who accomplished what others could not: “They [those who lived before Beethoven] were only like voices in the desert; / you are the savior who found the shore.”31 Smets’s ode also uses religious imagery—“From heaven the beams of consecration / fall upon the sons of earth”—and Kneisel’s second Festgruß claims that Bonn had been “chosen” as Beethoven’s dwelling.32 This biblical rhetoric accrues a more specific meaning in conjunction with the nationalist and sometimes martial language of the poems. Müller refers to the Ninth Symphony as a “song battle” (Liederschlacht), the sounds of which announce an approaching chorus of the Völker.33 Smets invokes the “all-conquering power of the human voice” and the “powerful fatherland,” and Kneisel, by far the most subdued, emphasizes Bonn’s connections with “all of Germany in association [im Verein].”34 Wolff’s text, on the other hand, avoids any national references.

If, as Kneisel’s poem claims, the monument signals Beethoven’s communal reentry, it also signals a temporal one as well, and it is in this removal of the temporal boundaries between the dead composer and the festival participants that the Bonn texts offer perhaps their most radical proposal: namely, that a Beethovenian timelessness could be conferred upon the Bonn celebrants. In Wolff’s text this claim is made at the end, when the chorus announces that the monument was erected by Beethoven’s contemporaries (Mitwelt): “In distant days / his image will tell posterity [Nachwelt] / how contemporaries honored him.” Turning the Bonn participants into Beethoven’s “contemporaries” not only erases the time between the ceremonies and the composer’s death eighteen years earlier, it also gives the celebrants a timelessness of their own. Without a past, and defined only by the future—via the monument they leave for posterity—the Bonn “contemporaries” who built the statue themselves gain an immortality and a twofold place in the “book of world history”: both as the Volk from which Beethoven came and whom he represents, and as those who honored him.

Figure 3. Beethoven statue in Bonn, by Ernst Hähnel.

A similar claim is made in the other festival texts. For Smets, the festival participants are an anticipatory generation from every time and place (“Vorgeschlecht von jeder Zone, jeder Zeit”) that will honor Beethoven. Beethoven enables the Volk’s posterity as much as its statue guarantees his: as the object of praise of “every Volk” he ensures a continuity in time and space for those who honor him, and in building the statue, Smets’s “Vorgeschlecht” sees its own immortality as well as Beethoven’s certified. It is worth noting in this context that Smets’s poem consistently addresses Beethoven in the present tense, a circumstance fitting a composer and a Volk without a past. Smets’s is a Beethovenian Volk that has escaped time and space: it is a Volk of the future.35 For Müller, Smets, and indeed Wolff, Beethoven represents nothing less than the very promise of posterity, a future in and enabled by music. Those who recognize in Beethoven and his music the galvanizing force of communal expression can find the means of both creating and prolonging heaven on earth. But it is important to recognize that this music, not unlike the festival in its honor, is not simply an object of veneration. It is also one of generation. And it is in this sense that we turn to the cantata Liszt wrote to Wolff’s text, for it is in the literal performance of Beethoven’s music (the “Archduke” variations) that the work’s communal subjects claim to be united—both with themselves and, it seems, with Beethoven himself, who is now claimed as a contemporary.

In Liszt’s cantata the extended quotation of Beethoven’s music comes at the end of the work. As Berlioz was the first to point out, it serves as an apotheosis.36 The moment is carefully prepared; it not only concludes the central narration of the cantata—the emergence of the genius—but is itself enclosed by self-referential markers beginning and ending the cantata: an announcement at the beginning of the work that “today is a festival day” and the claim at the work’s close that the festival has united its participants. Thus the “festival” to which the chorus refers, that which unites its participants, is not simply the Bonn festival in general but the middle narrative of the cantata, and most specifically the performance of Beethoven’s music at that section’s close. Not only does the inclusion of the “Archduke” material illustrate the communal effect of performing Beethoven’s music, but Liszt’s treatment of it, which both quotes the music and fuses it with his own, also serves to erase the temporal boundaries between Beethoven and the Bonn celebrants.

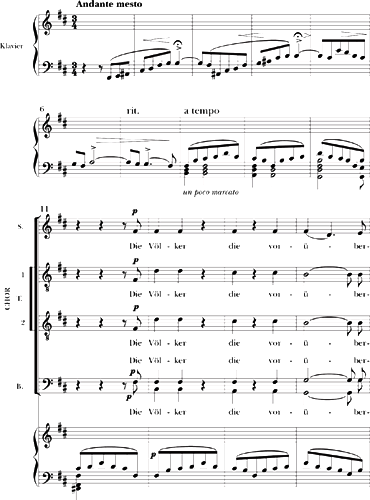

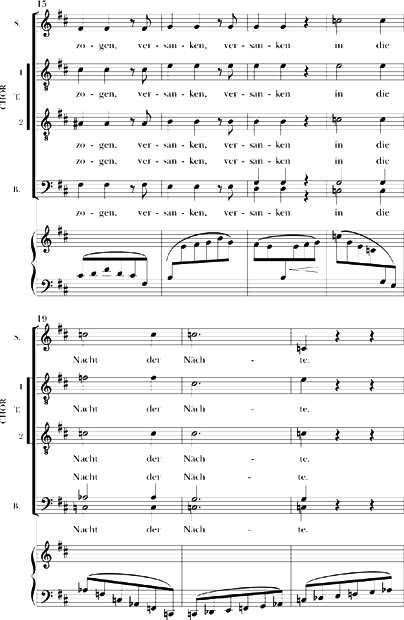

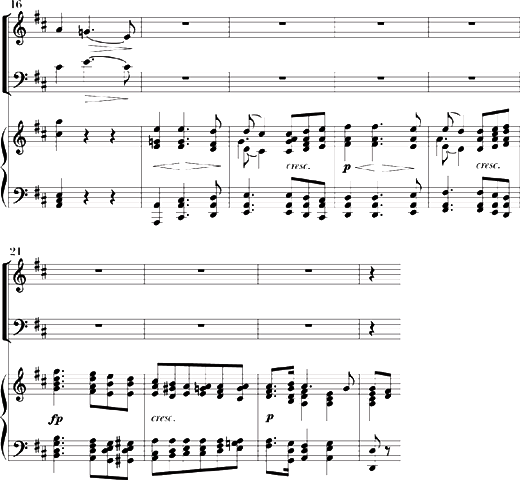

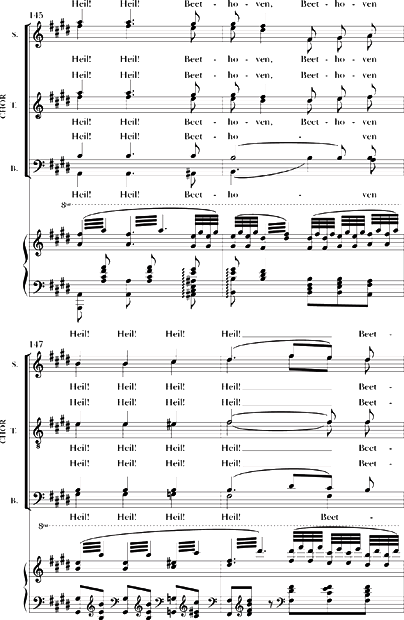

Yet before Beethoven arrives to escort his celebrants into heroic timelessness, Liszt makes sure to provide his forlorn Volk due pathos. Example 1 shows the beginning of the cantata’s third section, the depiction of the Völker that lack representation and a temporal anchor in the “currents of time.” This andante—“sad,” according to Liszt’s tempo marking—begins with a wandering cello line that suggests B minor, the local tonic, yet avoids a stable cadence. Its metric grouping is even more unstable, as the fermatas and accents avoid strong beats and create a continued sense of metric displacement. At measure 8 the “wandering,” evocative of the Völker without their genius, is followed by a rather maudlin accompanimental figure consisting of a descending tetrachord—the “emblem of lament”—in the lower strings and a repeated theme above it. This ostinato-like theme spans four beats, in contrast to the notated triple meter of the tetrachord below it; similarly, its dissonant passing tones against the bass add a further note of pathos.37 The chorus’s hesitant declamation in mm. 12–17 follows suit. If we are not entirely transported to a Baroque lament, Liszt’s music nonetheless conveys certain stylistic traits that confer a similar sense of seriousness and nobility upon the collective subject depicted in the text.38

Example 1. Liszt, Bonner Beethoven-Kantate, no. 3, mm. 1–25.

Example 1 continued

Example 1 continued

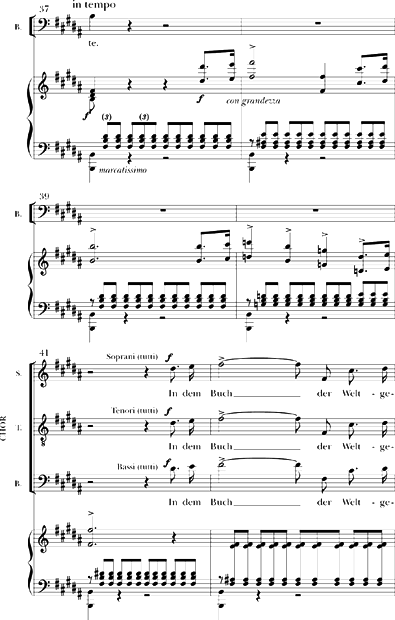

Following the B-minor lament it is announced that the prince will stand up for his country (Example 2). With a switch to B major, a dash of rhythmic brio—quick, marcatissimo triplets—and a broad new melody whose dip into flat six at measure 40 references the harmonic flavor of the whole cantata, the music appears to announce the Völker’s savior. A high-lying D-major tenor solo on this material starting at measure 49 seems to confirm this impression; just as the chorus sang of the Völker’s plight, so too would a gallant tenor sing of its redeemer. Although this setting appears almost too laudatory for the text’s ultimate message, such heroic music marking the prince’s advocacy for his people may have been a conciliatory gesture in light of the work’s more radical sentiments. Still, Liszt does offer one discordant note. At measure 48, when the text first refers to the “Fürst” and his purely political representation of the people, the harmony suddenly shifts from B major to G minor, as if to register that the heroic figure promoted in the preceding music and text is not its ultimate hero. The prince’s G-minor chord, a quick shudder that leads to the tenor’s D-major, signals dystopia rather than utopia, the minor flat-six as opposed to the major flat-six in which the genius will eventually appear. Indeed, this B-major section is immediately followed by an operatic soprano recitative emphasizing the shortcomings of the prince. The genius is announced finally at measure 129 with a return to E major and the fanfare that began the cantata; it is preceded, notably, by flat-six C major. The final section of the cantata ensues, starting with the “Archduke” quotation in C major.

Example 2. Bonner Beethoven-Kantate, no. 3, mm. 37–50.

Example 2 continued

Example 2 continued

It seems that Liszt had a particular fondness for the “Archduke” Trio. The work figured prominently in his Parisian concerts in the later 1830s, and he performed it throughout Germany in the years leading up to the Bonn festival.39 Yet the fact that he would choose the slow movement for his artist-prince, and that he would give this quotation the tempo marking Andante religioso, corresponds to a number of tropes in both Beethoven reception in general and the Bonn festivities in particular. For one, by the time of Liszt’s cantata an interpretive tradition was in place which viewed the Beethovenian slow movement generally in religious terms. Berlioz referred to the Adagio of the Fourth Symphony as the song of the Archangel Michael, and Friedrich Schmidt, an advisor to the Saxon court, contributed a poem to the 1846 Beethoven-Album in which the slow movement of the Ninth Symphony takes place on the “other side of the clouds.”40 Carl Czerny, moreover, specifically claimed that the third movement of the “Archduke” Trio has a “holy-religious” character.41 The same Friedrich Schmidt also added words to the “Archduke” variations for the Bonn celebrations, although it is not clear whether he did so after learning of Liszt’s cantata; Schmidt’s setting, entitled “Hymne von Goethe und Ludwig van Beethoven,” used the text “wer darf ihn nennen” from Faust.42

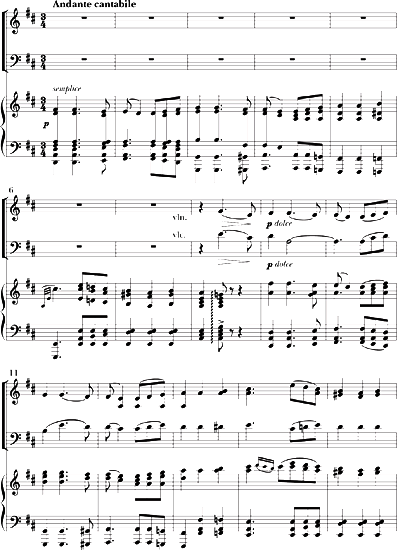

Schmidt’s title reflects the hymnlike character of the opening measures: its simple, stepwise melody, calm homophony, and measured phrase divisions (Example 3). Yet beyond these opening measures, there is little stylistic reference to religious music per se, especially given the avowedly secular genre of theme and variations. The religious nature of the movement seems to stem more from a prevailing sense of godly presence than one of human prayer. T. W. Adorno’s mid-twentieth-century description of the “Archduke” movement captures some of this sense: he heard an effect of “expressing tranquility through motion,” which he likened to the “personification and hypostatization of the ‘immanence’ or ‘presence’ of God.”43 In the “Archduke” variations this tranquility was a result of renouncing the “symphonic mastery of time”; the gesture “is that of setting time free, as if with an exhalation of breath, and as if it were impossible to linger on the paradoxical peak of the symphonic. Time claims its right….”44 Time does indeed “claim its right” in the movement, and on several levels. Obviously, the nature of theme and variations itself involves the sort of repetition and return that would generally deny the sense of constant development demanded by the “symphonic mastery of time.” The “Archduke” variations in particular always adhere closely to the theme, which remains audible and for the most part unchanged throughout. Moreover, the theme itself is structured around a return of sorts: the second phrase, starting at measure 17, leads back to the material of the opening measures at mm. 19–20, thus momentarily drawing this material into an almost cyclical relationship to itself. In general, the music’s expansive temporal and spatial unity accords with Liszt’s statement, quoted earlier, that the text celebrates “human Genius conquered by God in the eternal revelation through time and space.”

Example 3. Beethoven, “Archduke” Trio, op. 97, beginning of third movement.

Example 3 continued

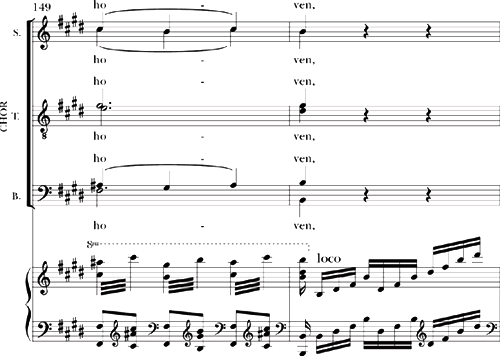

For the most part, Liszt’s quotation (Example 4) is straightforward. He puts the music in C major rather than the original D major. His boldest step, at least for present-day listeners, is the addition of Wolff’s text to Beethoven’s instrumental melody. But no contemporary seems to have voiced any objections to it; adding texts to Beethoven’s instrumental music was simply a common practice.45 What did draw response from critics was Liszt’s orchestration, which garnered almost unanimous praise.46 His practice of “developing instrumentation” throughout the quotation is clear from the start.47 The theme is first played by horns, bassoons, and trumpets; at the repetition of the first phrase, the lower horns and trumpets drop out and winds and the tenor solo enter; and at measure 13 in the trio, the tenor sings not the melody but an arpeggio line implied, but never written out as such, in Beethoven’s original.

Example 4. Bonner Beethoven-Kantate, no. 4.

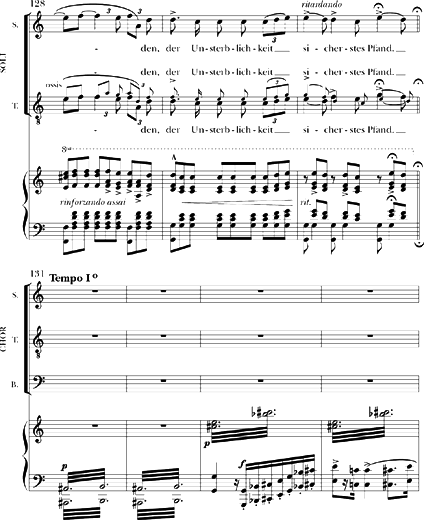

The rest of the variations continue much in this manner, with changing orchestration as well as varied voicing for the chorus and soloists, who often alternate the theme, an accompanimental line taken from Beethoven, or a descant lightly varying or implied in the original. Liszt simplifies some of the inner voices, evens out some of the syncopation, and skips entirely the second and third variations, perhaps because their filigree passagework could not so easily have been rendered by the large chorus. The transposition from D major to C major is important: it places the material in connection with the harmonic palette of the rest of the cantata, where C major as flat six was so frequent. Flat six itself may have had an idyllic connotation in the nineteenth century: Thomas Keith Nelson has proposed that it functions as the “Arcadian Pastoral,” an “oasis apart from the ongoing drama.”48 Although the variations were perched on the mediant rather than flat six in Beethoven’s trio (that is, D major in a B-flat-major work), in Liszt’s cantata the variations, set on flat six, seem a world away from the E-major fanfare. Yet at measure 131 (Example 5), Liszt makes the flat-six relation dramatically clear. Shortly before the end of what would be the fifth and last variation in the original, Liszt breaks off the quotation on the dominant, and after a fermata and a low tremolo on A# and B, the opening fanfare of the cantata sounds in measure 134, with the bottom Bs raised to C♮s as yet another flat-six coloring. The chorus sings “Heil Beethoven!” on unison Es, and soon the entire chorus and orchestra enter on the “Archduke” material, this time in a “variation” in the tonic E major starting at measure 143 composed entirely by Liszt himself. With the tremolos, fff marking, repeated Heils, and exclusion of all melodic material except the core of the “Archduke” theme, this moment would seem to mark Beethoven’s apotheosis.

This is also the very moment where we might locate another apotheosis as well, for here the massed performance forces come together as they have not before, and it is directly after this last “quotation” of the “Archduke” music that the fanfare enters once again, and the chorus claims that the festival has united them: unified through Beethoven’s music, the Bonn collective seems to have its own apotheosis. To be sure, Liszt’s cantata all but names Beethoven a god. But could Beethoven, the “heaven-sent” genius-prince and godly presence in Liszt’s “Archduke” variations, also cohabit that music along with the festival participants, as the Bonn texts claim? Put another way: can the flat-six idyll accommodate only a deity?

Example 5. Bonner Beethoven-Kantate, no. 4, mm. 128–50.

Example 5 continued

Example 5 continued

Example 5 continued

Example 5 continued

Perhaps—but perhaps not. The difficulty lies in both Beethoven’s and Liszt’s compositions. Adorno saw in the “Archduke” variations and those of Beethoven’s op. 111 a leave-taking. This reading of the latter work, itself immortalized in Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus, has received considerable attention from scholars concerned with Adorno’s diagnosis of Beethoven’s late style.49 But Adorno’s comments addressed both variation movements, and they seem particularly relevant to Liszt’s quotation of the earlier one:

[T]he true power of illusion in Beethoven’s music—of the “dream in stars eternal”—is that it can invoke what has not been as something past and nonexistent. Utopia is heard only as what has already been. The music’s inherent sense of form changes what has preceded the leave-taking in such a way that it takes on a greatness, a presence in the past which, within music, it could never achieve in the present.50

Adorno located the leave-taking at the end of the movements. The choice is logical, since the last set of variations marks a noticeable change in both the variation procedure and Beethoven’s harmonic vocabulary (Example 6). The variation is much more developmental than the others: it moves to F major before its dominant cadence at mm. 147–48, and the repeat of the first phrase modulates to E major by measure 155, signaling harmonic fluctuations that do not resolve until measure 174. Phrases are broken up and repeated at mm. 152–54 and mm. 157–62, which furthers the sense of “symphonic” development. This “developing variation” (literally and figuratively) signals the reemerging “symphonic mastery of time,” in Adorno’s words. The end of the variation seems to regain some of its timeless expansiveness, but it flows immediately into the next movement: once again at the “peak of the symphonic,” the music endows the “presence in the past,” the variations suspended in time, with a utopian greatness as the open cadence leads into the final movement.

It is precisely this moment, when the illusion of godly presence and “stars eternal” dissipates in Beethoven’s variations, that Liszt intervenes (see measure 131 in Example 5) by pulling the “Archduke” music into the E-major tonic and providing his own variation of Beethoven’s theme. Where Beethoven takes his leave, Liszt brings him back, and where Beethoven reenters time, Liszt denies it altogether. Liszt absorbs the open-ended, “leave-taking” variation into the festival music, and at the “new” variation starting at m. 143 it is no longer the case that Liszt’s music is looking back on Beethoven’s, or that Beethoven’s is sounding in posterity. The two are contemporaneous. And their contemporaneity is reflected in the text: it is here that the singers claim to inhabit Beethoven’s Mitwelt. Of course, taken alone the “Archduke” variations quite literally demand music in, if not of, the future—a Nachwelt—since they end on an open cadence, a B-flat seventh chord.51 In 1870 Liszt was to solve this problem by placing the quotation at the beginning of the cantata, as an extended slow introduction. But in 1845 Liszt not only composed music to follow Beethoven’s (the restatement of the fanfare and prince themes), music that seems to absorb Beethoven’s own; he also recomposed Beethoven after the latter had taken his leave. In writing an additional “variation,” and doing so in the tonic, Liszt and the collective he envoices did more than claim contemporaneity, a mutual presence in music. They made Beethoven’s music their own.

Example 6. Beethoven, op. 97, third movement, fifth variation.

Example 6 continued

Such claims had a different resonance in Weimar twenty-five years later. The intervening years had brought with them a panoply of composers and schools; there was, as Ferdinand Hiller proudly (if ambivalently) noted, “too much music.”52 For most contemporaries Beethoven was firmly a cultural memory: the likes of F. G. Wegeler, Ferdinand Ries, and Anton Schindler, all of whom knew Beethoven personally and had attended the Bonn festival, had no equivalents at the Weimar celebrations save for Liszt himself. The disappearance of a living memory of Beethoven gave way to the need for an heir apparent, and naming Beethoven’s successor lay at the heart of the New German debates that had engulfed the German musical establishment for over a decade (and would continue to do so).53 Brahms, of course, was made the standard-bearer on one side, although at this point he had yet to write a symphony; Berlioz had been dubbed the “French Beethoven.”54 The Weihekuss (kiss of consecration) Liszt purportedly received from Beethoven in 1823 had set in motion a series of popular images that sought to claim his Beethovenian pedigree not only for German nationalist narratives but for pan-European ones as well; Danhauser’s well-known Liszt at the Piano, picturing Beethoven’s bust and, among others, Rossini and Hugo, was initially titled Eine Weihemoment Liszts.55 Perhaps most famously, Richard Wagner’s commemorative “Beethoven” essay of 1870 places Beethoven in a nationalist telos ending with Wagner himself.

Such a telos had its institutional home in the Allgemeine Deutsche Musikverein (hereafter ADMV), which was founded by Franz Brendel explicitly to promote the New German cause.56 Although the association seems never to have had a particularly large membership, its concerts of new music organized for the annual meetings received substantial attention in the press, and the association was seen as a vigorous proponent of property rights for its composers.57 Liszt was named honorary president in 1873, and served as its public representative. Unlike the Bonn festivities, there was presumably little dispute whether Liszt would be a suitable composer for the association’s festival cantata. Along with Liszt’s contribution, there were works by Beethoven and compositions from ADMV members, such as a piano quintet by Joachim Raff, a Lacrymosa by Felix Draeseke, and Saint-Saëns’ Les Noces de Prométhée. Beethoven was represented by the Missa Solennis and several other late works (opp. 106, 131, and 135).58 Liszt’s cantata, which was both a “new” work and quotes Beethoven’s music, served as a link between the two honored parties of the Weimar festival: it aims to praise Beethoven as well as the music of the future.59

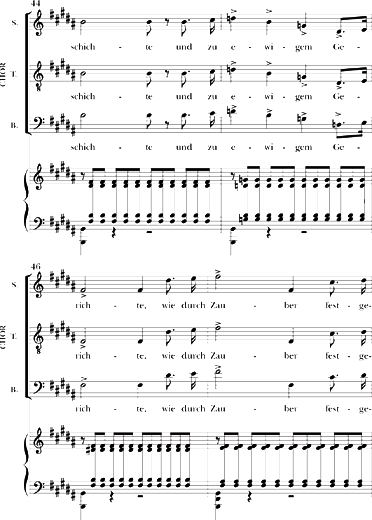

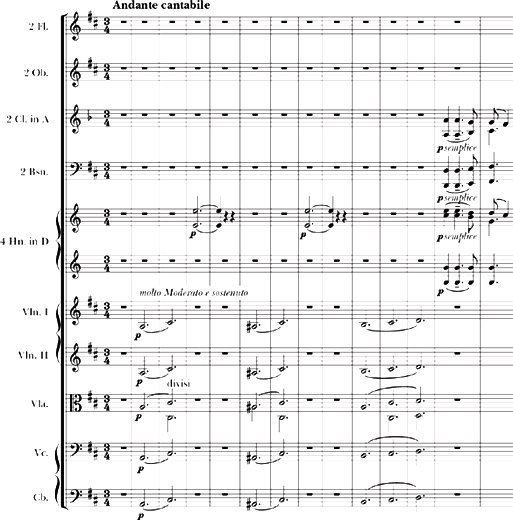

Liszt’s Weimar cantata shares with its Bonn forebear a distinct lack of national sentiment, although musical references to Bach and Wagner provide a strongly Germanic accent.60 The Weimar work also follows the Bonn one in ending on a self-referential note, with the claim “the highest that life preserves of spiritual power, to him it was given today, to him it was imposed. Hail Beethoven, Hail!” The 1870 cantata, likewise scored for chorus, orchestra, and soloists, similarly employs an extended quotation of the “Archduke” variations, although this time as an opening movement. But here—and most notably here—the similarities end. Beethoven and his music now seem to be memories: both in the literal sense, since almost a half-century had passed since his death and its quotation of the “Archduke” material recalls not only Beethoven’s original but also the 1845 work, and in the sense that Beethoven and his music were no longer claimed as a living presence. Now the object of a purely cultural memory—there are no claims for its everyday currency—Beethoven’s music seems to sound only at a distance. Example 7 shows the beginning of the cantata and its mysterious introduction by the strings and horns. Heard in retrospect, the introduction first outlines the mediant, followed by the submediant, before arriving at Beethoven’s original D-major tonic for the subsequent “Archduke” material. But as it sounds, without harmonic context, the chord progression is not without mystery. It seems to be taking us to a faraway place: the introductory chords function as a quotation mark.61 Whereas the fanfare opening and closing of the 1845 cantata will eventually signal a fusion with Beethoven’s music, its living presence, the opening measures of the 1870 work signal that music’s distance.

Unlike the Bonn cantata, the Weimar one gives the “Archduke” variations in full, in their original D-major tonic, and they even end on the original’s open cadence on the B-flat seventh chord—a momentary foray into a more chromatic space that has led one commentator to claim mistakenly that Liszt wrote the ending himself.62 In Axel Schröter’s words, the 1870 quotation is a “pure translation” of the trio’s variations for full orchestra; he even retains the violin and cello lines note for note.63 The variations have no text. The hymn topos of the opening measures in the original variations (to which the title of Schmidt’s 1845 setting alluded) is emphasized in Liszt’s orchestration for wind choir and horns, such that the tone of communal worship in Beethoven’s original now seems to be honoring Beethoven himself. Liszt’s orchestration is an act of faithful homage: it suggests Beethoven’s full canonization, but with it the crystallization of his music into inviolable citation.

The “Archduke” material, which Liszt published separately, is labeled as an introduction.64 The cantata that follows is not a small-scale work, as Liszt himself acknowledged.65 The text was written by Adolph Stern, a member of the ADMV board of directors, and upon Liszt’s request the poet and historian Ferdinand Gregorovius made several changes.66 The text is quite lengthy, and although Liszt offers a mostly syllabic setting with little textual repetition, the work is arguably too long.67 Even more so than he had in Christus or Die Legende von der heiligen Elisabeth, both recently completed, Liszt frequently assigns large chunks of text to unaccompanied recitative for the soloists as a means of getting through it all. But unlike the earlier oratorios there are no individual numbers—real or implied—nor any substantive musical repetition to break the narrative into readily intelligible parts after the end of the instrumental introduction; the only recurring motivic material is a short deformation of the “Archduke” theme that is occasionally employed to refer to the coming prophet. For the most part, the cantata consists of long patches of unaccompanied recitative, homophonic choral declamation, and orchestral quotations from Beethoven’s instrumental music. Recognizing the work’s potential shortcomings, Liszt wrote to Baron August, “Supposing that it’s a flop, at least it will be a painfully deserved one.”68

Example 7. Liszt, Beethoven-Cantate, no. 1, opening.

At the heart of the problem lies the text, which is shown on the next two pages in a highly shortened, though substantively unaltered, version. Despite its length, the text offers little more than a standard narrative of emergence: darkness penetrated by the light of a star; the coming of the prophet; and an encomium to the genius figure (Beethoven is only named at the end).69 It is a standard story, and indeed one familiar from Beethoven’s own “Trauerkantate” for Joseph II and its famous soprano solo with chorus—later incorporated into Fidelio—on the text “Da stiegen die Menschen ans Licht.” But in Beethoven’s work the “emergence” is countered by Joseph II’s death, and the subsequent return of the opening lament makes the otherwise standard narrative much more poignant. In Liszt’s cantata, the only substantial embellishment to this narrative is a description of sounds and sights that the cantata’s choral subjects do not understand. They are awoken by an unknown sound (“Do you hear the melody, not bells, not song?”) and they are perplexed by stars above the Rhine. Unable to interpret the phenomena, they call for the wise old man for an explanation; he foresees the coming of a “melodic prophet,” sent from God, who will transform human suffering into symphonies. The cantata closes with a paean to music as Beethoven’s star rises again to the heavens.

If the cantata is nominally set in 1770, insofar as it narrates Beethoven’s arrival on earth, its references belong solely to 1870. This is evident most notably in the cantata’s narration of the circumstances before Beethoven arrives. In place of the total darkness and despair found in the Bonn cantata, the Weimar narrative simply describes a winter night full of heavenly light. Although Stern employs strongly religious language to portray Beethoven as a savior figure—he is the heaven-sent prophet who will sound the “great last judgment”—Beethoven seems to enter a world considerably less needy of salvation; all that the community portrayed in the cantata seems to lack is an explanation of Beethoven’s appearance. This change in focus marks a systemic tension in the cantata, which tries to posit Beethoven as a singular prophet and simultaneously allow for other prophetic voices, namely those articulating the New German credo. If the Weimar cantata solved the problem of writing music to follow the “Archduke” variations by placing them at the beginning of the work, it created a possibly bigger problem of narrating Beethoven’s arrival after his music had sounded. Given the thoroughly contemporary music that narrates this emergence—signified above all by a bold quotation of the Tristan chord in measure 213, as the chorus describes the “peculiar shiver” they feel hearing such new music—the cantata must constantly negotiate the demands of praising both the historical Beethoven and a rather more abstract Beethoven identifiable as a contemporary, a Zukunftsmusiker.

Excerpts from the Weimar Cantata’s Text

| Sternenschimmernde, eisesflimmernde Winternacht voll himmlischen Scheins…rauschen die Wellen, glänzen silbern die Fluthen des Rhein’s. | Stars glittering, an icy glimmering winter’s night full of heavenly glow…the waves rush, silvery gleams the flow of the Rhine. |

| Kam nicht ein Tönen, das uns vom Schlummer…erweckte? | Was that not a note that woke us from our slumber? |

| Viel Töne schwirren leise, bald froh, bald seltsam trübe. | Many sounds whir softly, now merry, now clouded strangely |

| Ja, eintausend Sterngebilde erglänzen ob dem Rhein. | Yes, a thousand stars sparkle over the Rhine. |

| Hört ihr die Weise? Nicht Glockenschall, nicht Sang. Sehet empor, und der Himmel schimmert und blaut, wie wir’s nimmer und nimmer geschaut. | Do you hear the melody? Not bells, not song. Look above, heaven gleams bluely, as we’ve never ever seen it before. |

| Seltsamer Schauer hält uns umfasst. | A peculiar shiver holds us tight. |

| Ruft unsern weisen würdigsten Greis. | Call our wise and most worthy sage. |

| Er wird uns deuten den Wunderschein. | He will explain to us the wondrous glow. |

| Vater, Berather! Kannst du uns deuten das Wunder der Nacht? | Father, adviser! Can you explain to us the night’s wonder? |

| Es lebt die alte Sage von Zeiten fromm und fern, von einem Feiertage ihn kündiget ein Stern. Wenn tief die Himmel klingen in Sphärenmelodien, dann kommt am Himmels Bogen ein Cherub ernst und mild, durch Winternacht gezogen in einen Stern gehüllt. | There is the old legend from distant, pious times of a festival day announced by a star. When heaven deeply rings in melodies of the spheres, then on heaven’s arch comes a cherub solemn and gentle drawn through the winter’s night, enveloped in stars. |

| Es wird der Seele Sehnen nach jenen Harmonien aus seinem Busen tönen, in Schmerzens Melodien des Menschen tiefste Klage, den Zweifel seiner Brust, in Symphonien sagen und seine reinste Lust. | The soul’s longing for those harmonies will sound out of its bosom; in pain’s melodies symphonies will speak man’s deepest laments, the doubts of his breast, and his purest delight. |

| Zu des Aethers verschwiegenen Wonnen, zum Geheimniss der ewigen Sonnen, reichet den Schlüssel nur einzig der Klang. | To the secluded bliss of the ethers, to the mystery of the eternal suns, only music provides the key. |

| Die Völker all dem lauschen so still wie im Gebet, sein Ton kann nicht verrauschen, so lang die Welt besteht. | All peoples listen to him, still as in prayer, his music cannot die away as long as the world exists. |

| Der Stern ist aufgegangen in dieser Winternacht, gesegnet welchem leuchtet die goldne Strahlenpracht. | The star has ascended in this Winter’s night, blessed is he for whom the golden ray of splendor lights the way. |

| Heil Beethoven, Heil! | Hail Beethoven, hail! |

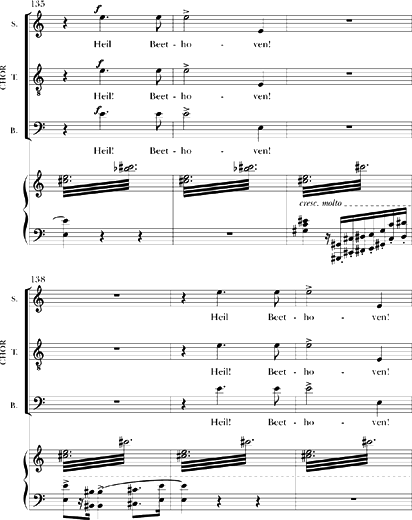

Although Stern’s text is itself caught between narrating a prophetic redemption and undermining the need for that redemption, this tension is magnified in Liszt’s musical setting. Indeed, it lies at the heart of the Weimar festival itself, which sought both to honor Beethoven and to celebrate contemporary music. Put simply, if Beethoven’s music—represented by the quotations—functions as a redemptive or transformative force in the cantata’s musical narrative, it thus minimizes the music that precedes it. Liszt’s music of the future would be superseded by Beethoven’s music of the past. And to some extent, this is precisely what happens. There is, for instance, a general move from the more chromatic Zukunftsmusik preceding Beethoven’s arrival to a more diatonic harmonic vocabulary organized in part around quotations of several Beethoven works at the moment of his arrival: the opening notes of both the Eroica symphony and the Fidelio overture, and the first theme of the 1805 “Leonore” Overture. The work ends on a triumphant, “Beethovenian” note, with repeated tonic chords and the Eroica motif dominating in the orchestra. The pure diatonicism of this quotation (it lacks the famous C#) seems to have transformed the chromaticism that preceded it, marking Beethoven’s heralded emergence and the omnipotence of his music.

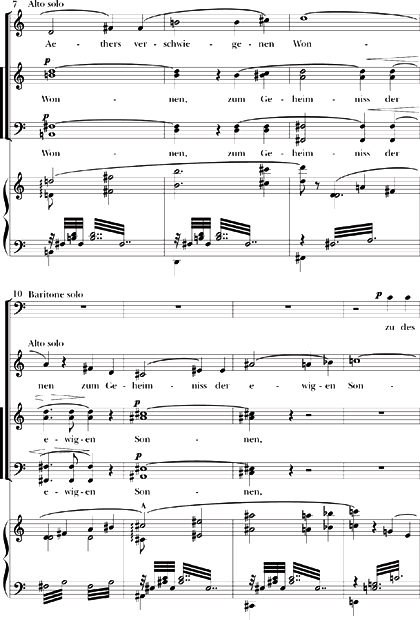

On the other hand, this diatonicism is thematic, not structural. The cantata occupies a thoroughly chromatic space: it is formed around E major, A-flat major, and C major. In its pervasive chromatic modulations and lack of extended tonic-dominant tension, Liszt’s cantata is New German music to the core. A slightly more extended example of the cantata’s progressive harmonic practice is given in Example 8. The setting of “Zu des Aethers verschwiegenen Wonnen” at mm. 693–702 is built on cascading arpeggios and the beginning of the chorale melody, but it focuses attention onto the harmonic sequence E-flat major—B minor—D major—B-flat minor—C major. The text claims that only music itself offers the key to “secluded bliss,” and Liszt’s music rather neatly illustrates this seclusion in its traversal of two pairs of hexatonic poles.70 E-flat major and B minor, for instance, share no common tones, and in functional harmonic language the chords can be related only with difficulty; B minor is the enharmonic minor six of E-flat major’s parallel minor. As opposite hexatonic poles they suggest the ultimate in harmonic distance, and it is precisely this sense of distance the text claims music can bridge, moving not only between one but two pairs of poles before ending the sequence. It is hard to imagine a stronger or more telling contrast to the 1845 cantata, and not simply because of the different harmonic language. In the Weimar work, the “music of the future” sounds at a distance—a “secluded bliss” in the ether. In the Bonn work, by contrast, the music of the future is the music of the here and now—of the Mitwelt—whose bliss is anything but secluded.

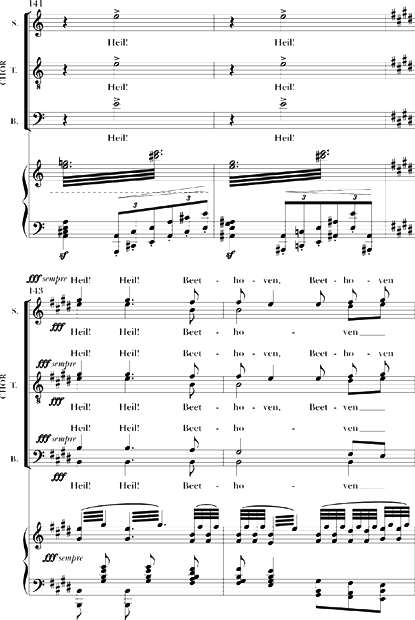

But it seems that seclusion, no matter how blissful, comes at a cost: the collective does not understand such music. Hence the “Archduke” theme reappears, in modified form, as an intriguing yet inscrutable promotion for a kind of music the chorus cannot yet call its own. Indeed, it is the treatment of the “Archduke” theme in the cantata proper—its “deformations” or misquotations by the incomprehending chorus—that provides the narrative pretense for the chorus to ask an old, wise man to explain the sounds. At measure 165 (Example 9), immediately preceding the text “Do you hear the melody,” an elementary version of the “Archduke” theme is heard in the orchestra; ascending in half-steps to its ultimate destination, E major, it lingers on D major in mm. 175–84. Clearly referring to the D-major variations that opened the cantata, this version of the theme is an undeniable invocation of music already heard, of remembered music. Yet the text, which refers to the “bright star” marking Beethoven’s heavenly emergence, insists upon its newness and the nascency of the “Archduke” material.71

Example 8. Beethoven-Cantate, no. 2, mm. 690–702.

Example 8 continued

What is this music? It has yet to crystallize into a clear musical thought—the community claims “never ever” to have seen such a vision, and cannot yet comprehend it or its accompanying music—yet it obviously alludes to the variations already heard. The deformation of the “Archduke” material is symptomatic of the cantata’s uneasy promotion of Beethoven as both the ghostly trace of the musical past and as an emerging avatar of the musical future. Of course, this ambivalence was systemic to the Weimar festivities as a whole, and Liszt’s cantata compensates for it with an increasing reliance on short, atomized quotations of Beethoven’s music. The music of remembrance and presence is supplemented by that of music-historical knowledge. Naturally, the cantata undeniably claims Beethoven as its true prophet. But in relying on the old man to explain Beethoven’s music, music that is “not yet” understandable, the cantata supplements its musical prophet (Beethoven) with a hermeneutic one (the New German exegete). He is called upon by the chorus to explain the sounds they do not understand—“only he alone,” they claim, can make sense of it all—and in doing so his function signals the abandonment of a communal, participatory role of the chorus in Liszt’s cantata: this is the music of the future as spectacle, not collective act. The cantata replaces as the recipients and bearers of musical understanding the community of listeners singing its text with the community of listeners attending the ADMV meeting. Indeed, the old man’s narration of the genius’s emergence is matched by a marked increase in the number of musical citations—those of Beethoven’s music, as well as the chorale melody “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern,” references any member of the ADMV would presumably have recognized immediately.

After Beethoven’s “arrival” and the chorus’s promise to honor its genius, the “Archduke” material returns once again on the text “The star is risen.” Like the new variation in the Bonn work, this one, at least at its start, is relatively faithful to the original. Although Liszt puts it in duple meter, it is completely homophonic and maintains Beethoven’s melodic shape. Musically, this moment may seem like a long-awaited arrival. Yet, crucially, the text stresses something else: a leave-taking. It announces that Beethoven’s star has now risen; he is no longer with the celebrants in the cantata. In contrast to the Bonn work, the Weimar cantata emphasizes not Beethoven’s presence but his absence at the climax of its narrative. Certainly he is not absent from the cultural, referential memory to which the cantata appeals; his is a spiritual presence, one the text promises will never die (verrauschen). But there is no claim to an everyday presence among the celebrants. He must be summoned, as he was in the mysterious chord progression introducing the variations, and his music will require exegesis to be comprehensible.

Example 9. Beethoven-Cantate, no. 2, mm. 164–71.

Like the Bonn work, the text ends on a self-referential note, and the C-major “Archduke” music is pulled into E major for the close of the work. To a degree, Liszt ends the Weimar cantata as he did the Bonn one, with the chorus singing a newly composed variation of Beethoven’s music and Heils in his honor in the final measures. But there is an important difference: whereas the 1845 cantata sought to deny Beethoven’s leave-taking, by claiming his enduring presence in the communal performance of his music, the 1870 cantata starts with his leave-taking (the final, developmental variation with the open-ended cadence) and subsequently narrates his arrival, only to announce that leave-taking yet again at the end. The cantata repeatedly reenacts his departure. It folds together the historical Beethoven, whose star has once again risen to the heights from which it came, and the referential Beethoven, the citations of whom now operate no differently than the chorale melody likewise announcing a star.

Thus, to continue the metaphor, two stars shine at the end of the Weimar cantata, one for each of its prophets: the canonized Beethoven of music-historical reference; and the group of composers gathered in Weimar who understand those references, and in whose name Liszt’s often ambivalent cantata seeks to claim Beethoven as one of their own. (The Bonn cantata, by contrast, had no use for stars: Beethoven was very much still “on earth,” embodied in those performing his music.) In this cantata musical meaning is no longer completely immanent to the work; it is reserved for those who possess the requisite cultural memory to recognize and process the quotations. The chorus in the cantata does not possess this cultural memory, and must ask the wise man for an explanation. To be sure, many associations in nineteenth-century Germany such as the ADMV saw the education of the public as part of their mission, and in this sense there is nothing necessarily exclusionary about the cantata’s delineation between those who understand the music and those who do not.72 But the very fact that this discrepancy is central to the narrative of the cantata illustrates the distance between the Bonn and Weimar works.

Liszt’s Bonn cantata promised a new temporality, one in which past, present, and future coincided, and the collected Volk joined Beethoven in an eternal Mitwelt of communal and musical presence. We might follow Walter Benjamin in approaching such a promise as that of messianic time: “Only a redeemed mankind receives the fullness of the past—which is to say, only for a redeemed mankind has its past become citable in all its moments.”73 Benjamin had a messiah other than Ludwig van Beethoven in mind, of course, but given the messianic properties attached to Beethoven in the 1845 work, such a characterization is not far off. In Wolff’s text, the Volk bereft of its genius was destined to perish in “the books of world history,” and it is Beethoven who comes to provide mankind with its revolutionary temporality, a past that has been recovered for an eternal present. This messianic temporality is driven home by the coexistence of Liszt’s own festival music with the citation of Beethoven’s “Archduke” material. In the 1870 cantata, by contrast, citing Beethoven has little to do with the “fullness of the past,” but rather its crystallization, the legitimization of an aesthetics of the future cut off from both the past and the community at large. Whereas Beethoven’s music seemed to provide the emancipatory means toward a communal future within music in 1845, by 1870 his music came to embody a future of music. What in Bonn had functioned as the gift of musical participation had become in Weimar the onus of musical progress, whereby the ossification of Beethoven as object of a new musical telos mirrors as well the ossification of the chorus, its role reduced to somewhat dimwitted spectators to whom both music and telos must be explained. In place of the Vormärz effusions of the Bonn work, the Weimar cantata substitutes the straightened realities of a political and cultural landscape that was significantly less likely to seek inspiration or even legitimization in “the people.” Perhaps Liszt had heeded the call of Peter Cornelius (another New German publicist) for composers to acknowledge that “the times of naïve creation, of sweet dreams of music, are past, that they have acquired reflection and self-criticism…that their composing and striving has thus to be ‘post-March,’ not ‘pre-March’ [i.e. Vormärz].”74

But although the Beethoven cantatas clearly participated primarily in a German public sphere, and in both festivities Liszt’s fellow participants attempted to honor Beethoven specifically as a German composer, it is important to point out that in both compositions neither the collective nor the figure of the artist-prophet is assigned a clear nationality. The works are indicative of Liszt’s nationalist principles more broadly, in which a Herderian conception of national culture rooted in the Volk joined forces with a liberal belief in collective agency and autonomy. It is a cosmopolitan aesthetic found throughout Liszt’s choral compositions. The Elisabeth oratorio, for instance, was finished in Rome, is dedicated to Ludwig II of Bavaria, tells the story of a Hungarian, and takes place at the Wartburg near Weimar. The 1874 choral ballad Die Glocken des Strassburger Münsters shares a similar background: with a text by Longfellow, a setting in Alsace, a musical forebear in Palestrina, and a premiere in Hungary that served as a fund-raiser for Bayreuth, the ballad illustrates how strongly a national and cultural eclecticism informed Liszt’s choral music well after the particularizing moment of German unification.

Of course, this kind of cosmopolitanism is not unrelated to a broader eclecticism supporting Liszt’s music more generally. The fundamental interdependence of secular and sacred aesthetics throughout Liszt’s oeuvre is one obvious example; so, too, is a wide confessional embrace witnessed, for instance, by the inclusion of the Bachian chorale “O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden” in the otherwise Catholic Via Crucis. Yet if the transportable “Volksgeist” ethos underlying much of the choral music is one of many wide-reaching tendencies that come together in Liszt’s music, it is a crucial one all the same. After all, the imagined voice of a noble collective is hardly limited to the choral music alone. Liszt’s call in 1835 for a religious music speaking as both God and Volk relates not only to the choral works of the 1840s that followed it, but the first version of the Harmonies poétiques et religieuses (1834) that preceded it. Although the piano work does not employ musical textures that immediately bring to mind a communal voice (such as the instrumental hymns in Ce qu’on entend sur la montagne, the instrumental “Hirtenspiel” in Christus, or indeed subsequent versions of the Harmonies), its opening quotation of Lamartine explicitly suggests the work’s generation in a collective subject: “We pray with your words, we weep with your tears, we plead with your song.”75

Such a mixture of singular and plural, of the individual and the communal, brings us back to the opening question posed by this essay—the extent to which we might see in Liszt’s advocacy of “the people” a mitigating force that discussions of his virtuoso personality and his multinational enthusiasms have tended to overlook. Works such as the 1834 Harmonies point the way toward a conception of the virtuosic solo works that is itself oriented around a communal aesthetic. Dana Gooley’s discussion of charity as a guiding force in Liszt’s concertizing is another fruitful approach.76 Obviously, the goal is not to whitewash Liszt’s career, to turn someone whose concerts seemed to exclude the “middle bourgeoisie” almost purposefully (and who, after all, tried to marry a woman with over 30,000 serfs) into an unimpeachably virtuous folk hero.77 But Liszt’s music and his career also illustrate a conviction that nations, the people who constitute them, and the cultures that define them shared an intrinsic value. Clearly the Weimar “Beethoven” cantata illustrates some of the limits to such idealism, as does the ambivalence of the “On the Situation of Artists” essay at the beginning of his compositional career. Yet to point out that prophet and populace do not maintain a steady equilibrium in Liszt’s choral works is to suggest no more—and no less—than that this imbalance reflects the contradictory forces of the nineteenth century more generally.

1. The term is Lawrence Kramer’s, although I hasten to add that his account does not necessarily promote this simplistic approach toward Liszt’s audiences. “Franz Liszt and the Virtuoso Public Sphere: Sight and Sound in the Rise of Mass Entertainment,” in Musical Meaning: Toward a Critical History (Berkeley: 2002), pp. 68–99.

2. Erika Quinn, for instance, writes: “Throughout the rest of his life [i.e. after the 1838 floods], Liszt used nationalist sentiments to serve his own personal purposes when possible.” “Composing a German Identity: Franz Liszt and the Kulturnation, 1848–1886,” Ph.D. diss., University of California, Davis, 2001, p. 58. For a comparative approach, see Gerhard J. Winkler, ed., Liszt und die Nationalitäten: Bericht über das internationale musikwissenschaftliche Symposium Eisenstadt, 10–12 März 1994 (Eisenstadt: 1996).

3. See, for instance, Dana Gooley, The Virtuoso Liszt (Cambridge, Eng.: 2004).

4. Carl Dahlhaus, Nineteenth-Century Music, trans. J. Bradford Robinson (Berkeley: 1989), p. 37.

5. The term was coined by Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (New York: 1991).

6. Paul Merrick, Revolution and Religion in the Music of Franz Liszt (New York: 1987).

7. The visit is reported in Alan Walker, Franz Liszt: The Virtuoso Years 1811–1847 (Ithaca, N.Y.: 1987, rev. ed.), p. 113.

8. The canonical account of the Saint-Simonians’ musical aesthetics, as well as Liszt’s interest in the movement, is found in Ralph P. Locke, Music, Musicians, and the Saint-Simonians (Chicago: 1986).

9. Dana Gooley has recently emphasized Liszt’s contributions to the German nationalist movement following the 1840 “Rheinkrise”; see “Liszt and the German Nation, 1840–1843,” in The Virtuoso Liszt, pp. 156–200.

10. On these three works see Merrick, “1848: Revolutions and a Mass,” in Revolution and Religion, pp. 26–35.

11. Letters of Franz Liszt, trans. Constance Bache (London: 1894), vol. 2, p. 33.

12. This formulation comes from Liszt’s “De la situation des artistes,” in Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 1: Frühe Schriften, ed. Rainer Kleinertz (Wiesbaden: 2000), pp. 56–59, here 59.

13. Michael Saffle notes that Liszt himself quoted Hanslick’s critique; see his “Sacred Choral Works,” in The Liszt Companion, ed. Ben Arnold (Westport, Conn: 2002), pp. 335–63, here 362 n. 13.

14. An impressively single-minded promotion of the oratorio’s Wagnerian credentials comes from Hans von Wolzogen, “Liszts ‘heilige Elisabeth’ auf der Bühne,” Aus Richard

Wagners Geisteswelt: Neue Wagneriana und Verwandtes (Berlin: 1908), pp. 275–88. For an interesting account of Elisabeth’s staged performances in Vienna, see Cornelia Szabó-Knotik, “Changing Aspects of the Sacred and Secular: Liszt’s Legend of St. Elisabeth in the Repertory of the K.K. Hof-Operntheater in Vienna,” in Nineteenth-Century Music: Selected Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference, ed. Jim Samson and Bennett Zon (Burlington, Vt.: 2002), pp. 169–78.

15. La Mara, ed., Franz Liszts Briefe, (Leipzig: 1893–1905), vol. 8, p. 415.

16. On democracy and associational life, see most recently Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann, “Democracy and Associations in the Long Nineteenth Century: Toward a Transnational Perspective,” trans. David F. Epstein, Journal of Modern History 75 (2003): 269–99. See also Klaus Tenfelde, “Die Entfaltung des Vereinswesens während der industriellen Revolution in Deutschland (1850–1873),” in Vereinswesen und bürgerliche Gesellschaft in Deutschland, ed. Otto Dahn (Munich: 1984), pp. 55–114; and Dieter Düding, Organisierter gesellschaftlicher Nationalismus in Deutschland (1808–1847): Bedeutung und Funktion der Turner- und Sängervereine für die deutsche Nationalbewegung (Munich: 1984). For an interesting comparative case, see

Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: 2000), much discussed recently in the American media.

17. Much has been written on associations in nineteenth-century Germany; most influential has been Thomas Nipperdey, “Verein als soziale Struktur in Deutschland im späten 18. und 19. Jahrhundert: Eine Fallstudie zur Modernisierung I,” in Gesellschaft, Kultur, Theorie: Gesammelte Aufsätze zur neueren Geschichte (Göttingen: 1976), pp. 174–205. See also Dahn; Christiane Eisenberg, “Working-Class and Middle-Class Associations: An Anglo-German Comparison, 1820–1870,” in Bourgeois Society in Nineteenth-Century Europe, ed. Jürgen Kocka and Allen Mitchell (Providence, R.I.: 1993), pp. 151–78; and Ralf Roth, “Von Wilhelm Meister zu Hans Castrorp: Der Bildungsgedanke und das bürgerliche Assoziationswesen im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert,” in Bürgerkultur im 19. Jahrhundert: Bildung, Kunst und Lebenswelt, ed. Dieter Hein and Andreas Schulz (Munich: 1996), pp. 121–39.

18. See, for instance, Wolfgang Tilgner, “Volk, Nation und Vaterland im protestantischen Denken zwischen Kaiserreich und Nationalsozialismus (ca. 1870–1933),” in Volk-Nation-Vaterland, ed. Horst Zilleßen (Gütersloh: 1970), pp. 146–49.

19. See Bernhard Giesen, Intellectuals and the German Nation: Collective Identity in an Axial Age, trans. Nicholas Levis and Amos Weisz (New York: 1998). On the role of the Volk in Enlightenment thinking, see Das Volk als Objekt obrigkeitlichen Handelns, ed. Rudolf Vierhaus (Tübingen: 1992).

20. On this imbalance, see Wolfgang Kaschuba, “Deutsche Bürgerlichkeit nach 1800: Kultur als symbolische Praxis,” in Bürgertum im 19 Jahrhundert: Deutschland im Europäischen Vergleich, ed. Jürgen Kocka with Ute Frevert (Munich: 1988), pp. 9–44.

21. John Williamson, “Progress, Modernity and the Concept of an Avant-Garde,” in The Cambridge History of Nineteenth-Century Music (New York: 2001), pp. 287–317, here 295.

22. Liszt, “De la situation des artistes,” p. 59.

23. Alan Walker, Franz Liszt: The Final Years 1861–1886 (New York: 1996), p. 209 n. 36.

24. On the change in German choral aesthetics following unification in 1871, see chapter 3 of my “National Memory, Public Music: Commemoration and Consecration in Nineteenth-Century German Choral Music,” Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 2005.

25. There are several first-person accounts of the festival: H. K. Breidenstein, Festgabe zu der am 12ten August 1845 stattfindenden Inauguration des Beethoven Monuments (Bonn: 1845; repr. Bonn, 1983) as well as his Zur Jahresfeier der Inauguration des Beethoven-Monuments: Eine actenmässige Darstellung dieses Ereignisses, der Wahrheit zur Ehre und den Festgenossen zur Erinnerung (Bonn: 1846; repr. Bonn, 1983); Hector Berlioz, “The Musical Celebration at Bonn,” in Evenings at the Orchestra, ed. and trans. Jacques Barzun (Chicago: 1999), pp. 326–44;

and Henry F. Chorley, “Beethoven’s Music at Bonn,” in Modern German Music, vol. 2, ed. Hans Lenneberg (New York: 1973), pp. 276–90. Of the many secondary accounts, see in particular: Hans-Josef Irmen, “Franz Liszt in Bonn oder Wie die erste Beethovenhalle entstand,” in Studien zur Bonner Musikgeschichte des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts, ed. Marianne Bröcker and Günther Massenkeil (Cologne: 1978), pp. 49–65; Lina Ramann, Franz Liszt als Künstler und Mensch, vol. 2, part 1 (Leipzig: 1887) pp. 249–65; Walker, Franz Liszt: The Virtuoso Years, pp. 417–26; Ingrid Bodsch, ed., Monument für Beethoven: Zur Geschichte des Beethoven-Denkmals (1845) und der frühen Beethoven-Rezeption in Bonn (Bonn: 1995); and Esteban Buch, Beethoven’s Ninth: A Political History, trans. Richard Miller (Chicago: 2003), pp. 133–55.

26. Alexander Rehding, “Liszt’s Musical Monuments,” 19th-Century Music 26, no. 1 (2002): 52–72, here 67.

27. Letter from 28 April 1845, in Letters of Franz Liszt, vol. 1, p. 96.

28. On the political content of Wolff’s text, see Andreas Eichhorn, Beethovens Neunte Symphonie: Die Geschichte ihrer Aufführung und Rezeption (New York: 1993), p. 301. On the Vormärz period, see in particular Christopher Clark, “Germany 1815–1848: Restoration or Pre-March?” in Nineteenth-Century Germany: Politics, Culture and Society, 1780–1918, ed. John Breuilly (New York: 2001), pp. 40–65 and David Blackbourn, “The Age of Revolutions,

1789–1848,” in The Long Nineteenth Century: A History of Germany, 1780–1918 (New York: 1998), pp. 45–174.

29. Rehding, “Liszt’s Musical Monuments,” p. 64.

30. See the following individual notes for citations of these texts. In general, an excellent sense of contemporary Beethoven reception—poems, addresses, reminiscences—can be gleaned from a Festschrift published just after the festival: Gustav Schilling, ed., Beethoven-Album: Ein Gedenkbuch dankbarer Liebe und Verehrung für den grossen Todten, gestiftet und beschrieben von einem Verein von Künstlern und Kunstfreunden aus Frankreich, England, Italien, Deutschland, Holland, Schweden, Ungarn und Russland (Stuttgart: 1846). For an interesting comparison with obvious correlates to Liszt’s second, 1870 cantata, see the (confusingly titled) Erstes Poetisches Beethoven-Album: Zur Erinnerung an den grossen Tondichter und an dessen Säcularfeier, begangen den 17 Dezember 1870, ed., Hermann Joseph Landau (Prague: 1872). A more in-depth consideration of both festivals, the two cantatas, and their social contexts can be found in chapter 2 of my “National Memory, Public Music.”

31. Müller, “Sie waren nur wie Stimmen in der Wüste; / Du bist der Heiland, der das Ufer fand,” in Landau, Erstes Poetisches Beethoven-Album, p. 255.

32. Smets, “Vom Himmelssaal der Weihe Strahl / herab auf Erdensöhne fällt,” in Breidenstein, Festgabe, p. 31.

33. On the importance of the Ninth Symphony for Vormärz liberalism, see Eichhorn, Beethovens Neunte Symphonie, pp. 298–317.