For the cosmopolitan and peripatetic Franz Liszt five European cities most shaped, supported, and sustained his life and career: Vienna, Paris, Weimar, Budapest, and Rome—indeed, the last twenty-seven years of his “vie trifurquée” Liszt more or less evenly divided among the final three.1 Paris was where, in his early teens, he adopted a new language and first came to international attention. The remaining city, Vienna, holds a special position. It lies less than sixty miles from his birthplace in Raiding, a small town in what was then the German-speaking part of Hungary. As a boy of nine Liszt and his father moved to Vienna. They lived there continuously for only eighteen months (1821–23), during which time Liszt studied with Czerny and Salieri, met Beethoven, published his first work, and gave prominent public concerts.2 After moving to Paris in September 1823, he did not return for fifteen years, until his pathbreaking concerts of 1838 at the age of twenty-six; he came back on tour the next year, and the next, as well as in 1846, and later visited Vienna numerous times, even on occasion performing.3 In the mid-1840s there was talk of him succeeding Donizetti as Kapellmeister, a move that would have made Imperial Vienna rather than the backwater Weimar his base of activity.4

The present documentary essay focuses on the crucial seven-week visit in the spring of 1838, which changed the course of Liszt’s life. Because of his earlier educational experiences there, Vienna had already proved a potent force, although in biographical tellings its role remains somewhat obscured by the relative paucity of documentation, and is in any case overshadowed by more sensational accounts of his subsequent training, young adulthood, and first legendary romances in France. The trip to Vienna in 1838 marked a turning point. Comparing his life to a classical five-act drama, Liszt later remarked that the second act (1830–38) concluded with the “return performances in Vienna, the success of which determined my path as a virtuoso.”5 (The third act of concert tours would last nearly ten years and take him across Europe and beyond.) Not only did Vienna deeply affect Liszt, but so too did he leave a mark on the musical life of this most musical of cities. As one critic put it at the time: “The good Viennese are quite changed” (Die guten Wiener sind wie ausgewechselt).6 Lending the sojourn further personal significance are the biographical issues that emerged from Liszt’s stay there, issues concerning his artistic, professional, and domestic situation, such as his legendary generosity, nationalist fervor, career aspirations, and the state of his deteriorating relationship with Marie d’Agoult, his companion for the past five years and the mother of his children.

Liszt’s time in Vienna, from 10 April to 26 May, is well documented in private and public sources, the latter with lengthy articles in the local and foreign press, which were followed by his own published account. This took the form of an open letter to the French violinist Lambert Massart that appeared in the 2 September issue of the Revue et Gazette musicale de Paris, and soon thereafter was translated for German, Austrian, and Hungarian periodicals.7 The importance of the trip in initiating the path Liszt pursued for the next decade has encouraged biographers to relate the events in far more detail than for other cities, and yet considerable confusion, misinformation, and an absence of local context make it difficult to assess meaningfully its significance. This essay aims to provide some sense of the cultural and musical climate in Vienna, to suggest ways in which Liszt’s reencounter affected both him and the city, and to clarify what was customary and what was novel about his activities.8 I shall look at the evidence from the “horizon of expectations” of the time, paying scant attention to what we know of Liszt’s subsequent life and career.9 Difficult as it may be to “bracket” such knowledge, there are advantages in trying to appreciate what would have been considered typical and atypical in the spring of 1838, how Liszt was viewed at this relatively early stage in his career, when he was much more the virtuoso than the composer, and before many, although certainly not all, of the legends surrounding him had taken hold. I will also speculate about what Liszt hoped to accomplish in Vienna and about the importance of this episode in his exceedingly careful and self-aware career development. I will consider in particular the artistic importance of his reconnection with the city of Beethoven and Schubert after years immersed in the musical life of France and Italy.

The documentary evidence for this investigation comes not only from Liszt’s own published account and letters, from the memoirs, letters, and diaries of others, from articles and reviews in the press, but also from those sources that allow us to reconstruct the nature of musical and concert life in Vienna.10 By beginning with some background information concerning the general musical scene in the 1830s, I hope to set up an informed context in which to consider what Liszt programmed, when and where he played, with and for whom, what prices he charged, and how he and others, not just the critics, viewed the results.11 His “enormous success” in Vienna offers the chance for a case study in the creation of a musical celebrity, a figure who would later become a central figure in musical Romanticism (FLC 315/86).12

Liszt arrived in Vienna at a particularly notable moment, with more than one critic remarking that 1837–38 was an unusually exciting season. A commentator in the Humorist exclaimed: “Concerts! Great Concerts! Everyone announces a great concert, but then gives a small one! No one announces a small concert that in fact turns out to be great. 1838 is a concert year! But a good one! Its planet is called: Liszt! When this planet leaves our orbit then I will lay down and not let the notes out and not attend any other concerts.”13 That season two other musical stars besides Liszt shone in the Viennese firmament: Clara Wieck and Sigismond Thalberg. Their presence provides an unusual opportunity to assess the situation of the piano virtuoso and composer. First, however, it would be wise to take a look at concert life in Vienna before the arrival of this notable trio.

Nicolò Paganini’s Viennese debut, which like Liszt’s would initiate years of touring, occurred exactly one decade earlier: the spring of 1828, a year after Beethoven’s death and eight months before Schubert’s. (Schubert attended at least one of Paganini’s concerts and is said to have commented that he “heard an angel singing.”)14 The violinist gave fourteen concerts over the course of four months (29 March to 24 July).15 His performances challenged critics to come up with sufficient superlatives. The poet, critic, and editor Ignaz Castelli wrote, “Never has an artist caused such a terrific sensation within our walls as this god of the violin. Never has the public so gladly carried its shekels to a concert, and never in my memory has the fame of a virtuoso so spread to the lowest classes of the population.”16

With the deaths of Beethoven and Schubert, as well as of some leading performers closely associated with them, most notably the celebrated violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh, an era in Vienna ended, closing what Raphael Georg Kiesewetter, in one of the first music history surveys, called “The Epoch of Beethoven and Rossini (1800–1832),” and what Eduard Hanslick, some thirty-five years later, would dub the “Epoch of Beethoven and Schubert, 1800–1830” in his classic history of Vienna’s musical life. Now began, in Hanslick’s estimation, “The Era of the Virtuoso: Thalberg and Liszt, 1830–1848.”17 Yet many aspects of Vienna’s concert scene continued as they had for decades, with a season that began around late October and ended in May. (Paganini’s summer appearances were unusual and initially unplanned—he kept on extending his stay and adding concerts.) Much of it was still guided by the same institutions Beethoven and Schubert had known. Each season the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, founded in 1812, presented Society Concerts (Gesellschafts-Concerte) devoted to orchestral music, as well as Evening Musical Entertainments (Musikalische Abendunterhaltungen) offering chamber and vocal music. The Concerts Spirituels also featured orchestral and choral works, but at what was generally regarded as a lower level of execution. Charity concerts were common, especially around Easter, typically given either by established organizations or in response to a specific circumstance, such as to honor a noted figure or in response to some natural disaster.

Beyond the institutional and charitable offerings, composers and performers presented their own concerts (an “Akademie,” as it was usually called), which they organized themselves and from which they reaped the financial rewards (or not). The frequency of such events escalated considerably in the 1830s, with an increasing number of virtuoso performers coming from abroad. Prodigies—or young performers of sometimes questionable ability who claimed to be worthy of attention—regularly gave concerts. Concerts almost always included an orchestra, usually one associated with a theater (such as Theater an der Wien and Theater in der Josephstadt) and conducted by figures like Leopold Jansa, Georg Hellmesberger, and Karl Holz.

The format tended to be fairly uniform: an overture to start (most frequently one by Beethoven or Mozart), followed by a work for the featured performer, in either a concerto or a solo piece. Vocal music often came next, or a “declamation,” delivered by an actor from the Imperial Court Theater. Concerts usually ended with the featured performer, sometimes playing an original composition or improvising. The participating instrumentalists were mostly members of one of the city’s orchestras, for either the Court or one of the suburban theaters; some were also professors at the Conservatory, yet another institution that regularly presented concerts. In addition, there was the stable of actors from the Court Theater who gave the declamations.18 Despite rivalries and factions, these dominant musicians and actors performed together; visiting artists, including Wieck and Liszt, had to obtain their services.19 Charity concerts brought performers together, sometimes in rather unusual combinations. At one such occasion, on 13 March 1831, sixteen pianists, two seated at each of eight instruments, performed the overtures to Rossini’s Semiramide and Beethoven’s Egmont as arranged by Czerny. The playbill lists a veritable who’s who of Viennese pianists at the time: Czerny, Franz Chotek, Theodor Döhler, Joseph Fischhof, Georg Lickl, Albin Pfaller, Wenzel Plachy, Thalberg, and “eight other excellent artists and friends of art.”

Musicians also gave benefit concerts (as distinct from charity concerts) in the less altruistic cause of supplementing their personal incomes. The case of Leopold Jansa—a local violinist, conductor, composer, and professor at the Conservatory—is typical. His concert on 23 April 1835 at the hall of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, the Musikverein, followed the expected format: after the Egmont Overture, came his own Concerto for Violin in E Major, and then Heinrich Proch’s “Der Blinde Fischer,” a new song with Waldhorn obbligato performed by Ludwig Tietze, Eduard Lewy, and the composer. This was followed by Thalberg playing one of his caprices “for the first time publicly,” and the concert ended with Jansa, Proch, Karl Holz, and Joseph Lincke performing his Concerto for Two Violins, Viola, and Cello. Three years later, Jansa gave an Akademie that opened with Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture, followed by his own Violin Concerto in B Minor, a declamation, Hummel’s Piano Trio in E (with Aegid Borzaga and Fanny Sallamon), a duet from Pietro Generali’s opera La donna soldato, and concluding with an impromptu for violin by Jansa. Such concerts show the expected heterogeneous combination of music and recitation, the participation of local colleagues, and the limited use of an orchestra to open the event and to accompany soloists.20

The magnitude of Liszt’s series in 1838 becomes clearer when profiled against concerts by other virtuosos. Most relevant are the many pianists, both local and visiting, who performed in the 1830s, occasionally in a series of two or three concerts grouped together within a fairly short period. Among the leading foreign pianists to appear were Ludwig Schunke, Adolph Henselt, and Johann Nepomuk Hummel, all noted composers as well.21 Pianists residing in Vienna included Carl Maria von Bocklet, whose students (among them Alois Tausig and Caroline Herrschmann) also gave concerts, and the young Louis Lacombe, a student of Czerny’s. Bocklet (1801–81), who had premiered much of the chamber music of Beethoven and Schubert at Schuppanzigh’s concerts, offered programs that were unusually spare and serious; four in 1835 are representative:22

10 April

Overture

Hummel, Piano Concerto in B Minor

Aria from Mozart’s Titus

Improvisation

20 April

Overture

Hummel, Piano Concerto in A Minor

Vocal work

Improvisation

29 November

Moscheles, Piano Concerto in E flat Major

Weber, Konzertstück Improvisation

20 December

Hummel, Piano Concerto in A flat Major

Moscheles, Concert fantastique (manuscript)

Improvisation

A large number of women pianists, following Leopoldine Blahetka in the 1820s, were regular presences in Vienna, among them Herrschmann, Nina Onitsch, and Nina Delack.23 Fanny Sallamon appeared most often in the 1830s. Her concert at the Musikverein on 2 February 1832 began with the standard Beethoven overture but also, unusually, featured a Beethoven sonata, specifically the “Appassionata,” of which Wieck’s performance six years later would cause a stir:

Beethoven, Egmont Overture

Hummel, Piano Concerto in A-flat Major

Lachner, “Fragen,” song with cello obbligato, sung by Ludwig Tietze, with Joseph Merk and the composer accompanying

Jansa, New Adagio and Rondo for Violin and Orchestra

Beethoven, “Grosse Sonate” in F Minor

The rise of the instrumental virtuoso in the 1830s promoted a comparative musical culture. Performers were judged not only on their own merits but also in relation to others, with the foundational model being Paganini. Liszt aspired to be the “Paganini of the Piano,” and it did not take long before exactly that label was repeatedly applied to him. The comparative contest was promoted in the press, which helped to create a culture of performing celebrities. A certain governing logic made comparisons far from odious, but rather inevitable.

By the time Wieck and Liszt appeared during the 1837–38 season, six celebrated musicians had won the official imprimatur of the special title k. k. Kammervirtuoso (Imperial and Royal Chamber Virtuoso): Paganini and Thalberg, cellist Joseph Merk, violinist Joseph Mayseder, and singers Giuditta Pasta and Jenny Lutzer.24 The designation carried not only prestige—those honored tended to display the title proudly—but also privileges because they were considered “subjects of the Austrian Empire in all countries and always under the protection of the Austrian envoys.”25 Both Wieck and Liszt hoped they would be granted the title during their stays.

The principal comparative contest in Vienna was among pianists, even if the name of Paganini was invoked as a cultural and musical touchstone. Thalberg, at twenty-six just three months younger than Liszt, had already become the local standard-bearer. Although he was born in Geneva, Thalberg had been familiar to Viennese audiences for more than a decade and enjoyed especially close ties to the city as a member of a powerful aristocratic family, the Dietrichsteins.26 He and Liszt had already had their run-in in print, the salon, and concert hall; Vienna renewed the contest. As Liszt wrote to Marie d’Agoult immediately after his second appearance: “The Thalbergites (for these comparisons will never end), who prided themselves on their impartiality to begin with, are beginning to be seriously vexed” (FLC 318/87).

Clara Wieck’s presence expanded the field and provided the press with more to write about. Before she had played a single note in public, Adolph Bäuerle, the influential editor of Vienna’s Allgemeine Theaterzeitung, wrote that this “famous artist, who has just triumphed in Prague, has arrived here and will give concerts in the middle of this month. We are making the public aware of the modest young artist who ranks alongside Liszt and Chopin in Germany. Vienna shall decide if she can hold her own next to Thalberg.”27

Such comparisons were not only made in the press and among the musical cognoscenti, but also were very much on the minds of the artists themselves. As Clara Wieck’s father, Friedrich, a noted piano pedagogue, was preparing her for her first concert, he wrote in her journal: “Although Thalberg’s name is on every tongue here, they know very well that he plays coldly and is also not a masterful composer—he is also reproached because he plays only his own works” (7 December). The Neue Zeitschrift für Musik reported that the concert caused a “sensation that no artist has aroused since Paganini and Thalberg.”28 Clara called it “my triumph” in her diary and noted, “The audience generally affirmed that I have a higher standing than Thalberg. Father says, ‘Why compare? Cannot two artists exist side by side?’” Yet Friedrich must have been pleased that the comparisons were being made to Clara’s advantage, for following her third concert he boasted of her “complete victory over Thalberg” (14 December and 7 January). Clara’s strategy extended to performing music by the competition on her next concert: “I played pieces by Liszt and Thalberg to silence those who thought I couldn’t play Thalberg. There were 13 curtain calls, and not even Thalberg experienced that.”29

Liszt was even more attuned to this competition among pianists. Indeed, aspects of it had already been partially played out the year before in his “duel” with Thalberg at a charity event in Paris. The result had been a draw, with the hostess, the formidable Italian Princess Cristina Belgiojoso allegedly declaring, “There is only one Thalberg in Paris, but there is only one Liszt in the world.”30 Rainer Kleinertz has argued that Thalberg was an “idée fixe” for Liszt during these years, and indeed his correspondence is filled with obsessive references to his rival.31 In this context, a private letter Liszt wrote to Massart just after leaving Vienna is almost comical: “Thalberg, whom I don’t like to quote and towards whom I only keep the most religious silence, said some nice enough words to me that capture well the situation in Vienna: ‘In comparison with you I have never had more than a succès d’estime …’ That is perfectly true, but I pray you not repeat it, as I want to avoid, as much as is possible, all comparisons. I more or less have that ambition.”32 We shall later examine some of the critical comparisons made in Vienna about the reception of Thalberg, Wieck, and Liszt, including a well-known article in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik that ranked the virtues of each of them in order.33

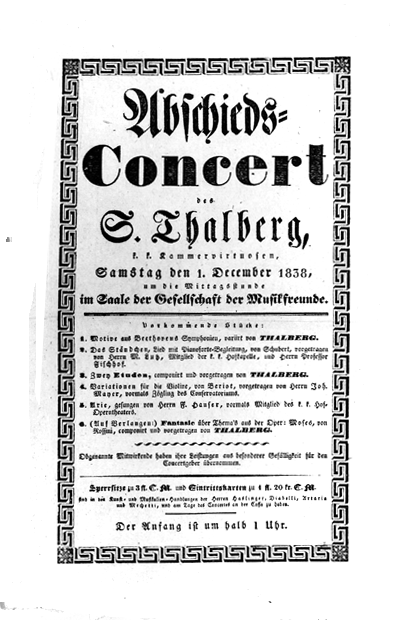

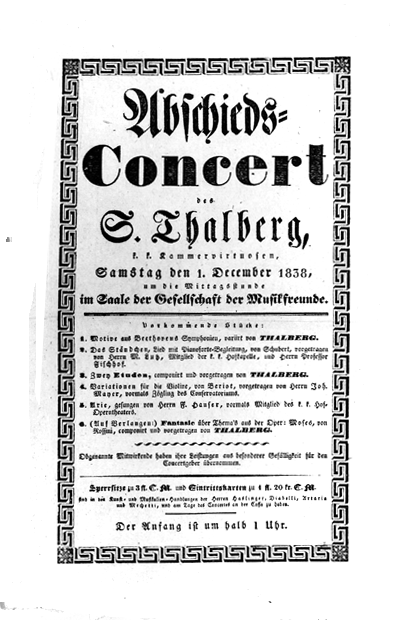

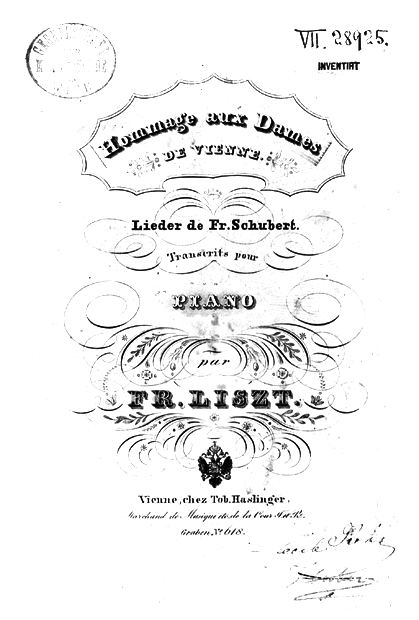

When he returned to Vienna in 1838 Thalberg was well known to local audiences. He had appeared there as early as 1827, at age fifteen, playing frequently in private circles and public concerts.34 He toured Germany in 1829, England the next year, and was establishing himself in Paris by the mid-1830s, all the while frequently returning to Vienna and participating in concerts given by the various musical societies and institutions, as well as in charity concerts, including one in 1830 to help victims of a serious flood that year. In addition, Thalberg’s compositions, unlike Liszt’s, were widely performed in Vienna by other pianists.35 Because of his family, he enjoyed broad aristocratic connections and Court support. His three concerts at the Musikverein in November and December 1836, which Hanslick would later credit with initiating a new era, give a representative idea of his repertory. (The complete programs are given in table 4 at the end of this essay.)36 Thalberg also planned three concerts late in 1838, but the first two were canceled.37 (See figure 1.) As Friedrich Wieck commented, Thalberg, like Paganini before him, generally played his own music, which constituted a crucial difference from the programming of Clara Wieck and Liszt, who mixed their own works with those of others. Thalberg’s concerts in late 1836 were well received, with a review in the Leipzig Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung stating that Thalberg, “the feted hero of the day, gave three concerts at high prices before audiences as large as they are elite. He played everything, without orchestral accompaniment, on a heavenly English piano that had been given to him in Paris by Erard.”38

Figure 1. Playbill of Sigismond Thalberg’s “Farewell Concert” on 1 December 1838.

Exactly one year later the Wiecks arrived in Vienna, following concerts in Prague. Clara’s public appearances between December 1837 and April 1838 were unprecedented in quantity for a pianist and could just as rightly be said to have been epoch making—indeed, that is exactly what Friedrich declared after her second concert, on 21 December: “Clara has founded a new era in piano playing in Vienna with this concert.”39 The eighteen-year-old pianist spent nearly five months in Vienna with her father; her extensive and unusual activities thus directly preceded Liszt’s arrival and she stayed on expressly to meet and hear him. Recounting the full and fascinating story of her time in Vienna is beyond the scope of this essay; much of it is related in Friedrich’s letters to his wife back in Leipzig, as well as in the diary Clara kept at the time (in which her father also often wrote).40 She also made relevant comments in clandestine letters written to Robert Schumann, to whom she was already secretly engaged.

The Vienna concerts marked Wieck’s first great career success, proving extraordinarily popular as well as lucrative. She was showered with gifts, including manuscripts by Beethoven and Schubert, and with honors, from a torte named after her to dedications of poems and music. Before Wieck, visiting performers tended to give just two or three concerts. (Paganini’s fourteen in 1828 were unprecedented, all the more unusual in that most of them took place “off season.”) Her visit thus began in the expected way: two concerts were announced (14 and 21 December); after the third on 7 January, she gave another on 21 January, which was billed as the “fourth and last” (see figure 2), but then “by request” she added two more (11 and 18 February).41 (Table 5 at the end of the essay gives the complete programs of her solo concerts.)

Some aspects of her concerts were typical, such as the use of an orchestra (the one for the Josefstadt Theater under Heinrich Proch), the participation of local virtuosos and actors, and the mixture of genres and composers. From the beginning it is clear that she and her father planned her repertory carefully and waited for success with audiences before going on to program especially challenging pieces. The general seriousness of her concerts was remarked upon, including “early music”—Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp Major in particular caused quite a stir.42 Her performance of Beethoven’s “Appassionata” Sonata aroused special admiration, but also some controversy over her interpretation.43 The celebrated writer Franz Grillparzer was inspired to write his well-known poem “Clara Wieck und Beethoven (f-moll Sonate),” which was widely reprinted at the time (Liszt included it in his open letter to Massart) and set to music by Johann Vesque von Püttlingen:44

A wizard, weary of the world and life, locked his magic spells in a diamond casket, whose key the threw into the sea, and then he died.

Common, little men exhausted themselves in vain attempts; no instrument could open the strong lock, and the incantations slept with their master.

A shepherd’s child, playing on the shore, sees these hectic and useless efforts. Dreamy and unthinking as all girls are, she plunges her snowy fingers into the waves, touches the strange object, seizes it, and pulls it from the sea. Oh! What a surprise! She holds the magic key!

She hurries joyfully; her heart beating, full of eager anticipation; the casket gleams for her with marvelous brilliance; the lock gives way.

The genies rise into the air, then bow respectfully before their gracious and virginal mistress, who leads them with her white hand and has them do her bidding as she plays.45

Wieck’s six concerts were, however, only part of her participation in Vienna’s musical life, which extended to various charity events and Court appearances, not to mention the many occasions on which she played at the private homes of aristocrats and musicians. The list of her public and semipublic appearances alone is daunting (see table 1). I know of no other pianist before Liszt who gave so many individual concerts in such a concentrated period; the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik commented that no performer had done so since Paganini.46

Figure 2. Playbill of Clara Wieck’s concert on 21 January 1838.

Table 1. Clara Wieck’s Appearances in Vienna 1837–38

Liszt’s youthful Vienna appearances in the early 1820s had long since faded from memory when he returned in 1838. His recent concert repertory in France, Italy, and elsewhere was, not surprisingly, similar in some respects to what he would present in Vienna, although he had never before given so many concerts in such a concentrated time. In contrast to Thalberg, Liszt’s own compositions played less of a role in his concerts. He continued to juxtapose virtuoso works with more serious and unfamiliar fare, including piano sonatas and chamber music.47 Liszt also became increasingly engaged with the music of Beethoven and Schubert. In Paris he had performed Beethoven sonatas and chamber music, and accompanied singers, especially the celebrated tenor Adolphe Nourrit, in Schubert songs. In the year or so before coming to Vienna Liszt had put much of his energies into transcribing Beethoven symphonies and Schubert songs. This, too, may have been a reason for his desire to reengage with the city of these two masters. Beethoven had been dead just eleven years, Schubert less than ten. They were still in the living memory of the Viennese.

Part of the allure of Vienna, no doubt, was the chance to connect and reconnect with close associates of both Beethoven and Schubert, ranging from Czerny and the publisher Tobias Haslinger to less familiar figures like Johann Baptist Jenger, Ludwig Tietze, and Benedict Randhartinger (a fellow classmate from the time when they studied with Salieri), all three of whom joined him in concert. Liszt left a particularly moving account of hearing Baron Carl von Schönstein, an amateur singer Schubert had highly praised and to whom he dedicated Die schöne Müllerin, sing some Lieder privately one evening.48 Vienna was a musical mecca for musicians of a certain sensibility who wanted to continue to participate in the substantive musical tradition of Haydn and Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. Clara Wieck thought that once she and Schumann married they might move there, and their correspondence shows plans evolving. Schumann, who had not yet visited the city (he would go later in the year), was keen on the idea: “Don’t you know that one of my oldest and fondest wishes is to live a number of years in the city where Beethoven and Schubert lived?”49 At some point Liszt evidently made a comment about doing the same thing, for Clara informed Robert, “I am really afraid that Liszt might move to Vienna, which he wanted very much to do.”50

Liszt had been planning his return to Vienna for some time, well before the floods in his native Hungary, which he claimed (and posterity has generally believed), prompted his swift departure from Venice and Marie d’Agoult in April 1838. According to his later published account, it was only in early April that he learned of the devastating flood of the Danube the previous month:

I had become accustomed to considering France my homeland, forgetting completely that it was really another country for me…. How could I not believe that I was the child of a land where I had loved and suffered so much! How could I possibly have thought that another land had witnessed my birth, that the blood coursing through my veins was the blood of another race of men, that my own people were elsewhere…? [After reading of the flood] I was badly shaken by it. I felt an unaccustomed sense of compassion, a vivid and irresistible need to comfort the many victims…. Oh, my wild and distant homeland! Oh, my unknown friends! Oh, my vast family! Your cry of suffering has summoned me to you!…I left for Vienna on the 7th of April and planned to give two concerts there: the first for my countrymen, and the second to pay for my traveling expenses.51

Here, as in his letters, in contemporaneous press accounts, and in a police report from the time, it is absolutely clear that Liszt presented only one concert to aid the flood victims.52 Yet many biographies of the composer state that he gave eight such charity concerts, raising a huge amount of money for the cause. Although recent scholars have usually gotten the facts right, Liszt’s most influential modern biographer, Alan Walker, has consistently perpetuated errors concerning what he calls Liszt’s “eight charity concerts,” and seems determined to press the point that Liszt’s sole motivation for the trip was nationalistic: “Hungary, and Hungary alone, was the reason Liszt found himself in Vienna.”53

Not only was there just one charity concert, but there is also good reason to question whether Liszt’s trip was really prompted by the flood, by “Hungary, and Hungary alone.” He had hoped to conquer Vienna and intended to concertize there without any charitable impetus. Plans were announced in the German press late in 1837.54 Friedrich Wieck mentioned it in a letter to his wife in November, and Clara passed it on in a Christmas Eve letter to Robert (Liszt is “not yet here but is daily expected”).55 Throughout his life Liszt was a long-range planner, and Vienna was an attractive place—probably the most attractive—to start a new stage of his career, which he had been ruminating about for some time already.56 Dana Gooley has argued that the charity concert for the flood victims was a “pretext” for going to Vienna and that Liszt’s principal motive was more likely the desire to show up Thalberg on his own turf and perhaps to make money and to get away from d’Agoult.57 It is, of course, impossible to determine his motivations, which no doubt were many and complex, but they were surely not as simple and altruistic as often presented.

By mid-March the seriousness of the Danube flood, which marked a defining moment in Hungary’s history, was widely publicized. Given the extent of the devastation, it is hardly surprising that there were many events to help the cause, most of them before Liszt’s—indeed, his concert was one of the very last. As early as 19 March the forever calculating Frederick Wieck commented that it was time to leave Vienna: “We must go—Clara can only lose from this point on. If she remains here she must play six more times for other causes—[the English singer Clara] Novello would like to replace us here. The terrible misfortune in Pest makes it difficult to give concerts just for one’s personal gain.” By this point Clara had given her six individual concerts. As she wanted to meet Liszt, she left Vienna briefly to perform two concerts in Pressburg and upon returning, Friedrich noted: “The abundance of concerts is frightful” (3 April). Clara wrote to Robert: “Concerts for the people in Pest are endless, and they are always packed.”58 Table 2 lists some of the concerts for the flood victims leading up to the one by Liszt.59

Table 2. Selected Charity Concerts for Flood Victims of Pest and Ofen in 1838

29 March |

Concert at the Conservatory (including Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony) |

1 April |

Arcadius Klein in k. k. Redoutensaale (featuring Clara Novello, Richard and Carl Lewy, Baron Carl von Schönstein, Moritz Saphir, and others) |

1 April |

Concert at k. k. grossen Universitäts-Saale (“Eine grosse musikalische-declamatorische Akademie,” with Georg Hellmesberger conducting) |

3 April |

Concerts Spirituels (featuring Clara Novello, Julie Rettich, Fanny Sallamon, and Ignaz Ritter von Seyfried conducting Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony) |

5 April |

Charity concert (featuring Clara Wieck) |

5 April |

Joseph Geiger, piano (featuring Joseph Staudigl, Aegid Borzaga, Benedict Randhartinger, Jenny Lutzer, and conducted by Hellmesberger) |

7 April |

Moritz Saphir’s Akademie |

11 April |

August Anders, fourteen-year-old pianist |

15 April |

“Musikalische Akademie” for Pest and Ofen |

16 April |

Adolph Pfeiffer, twelve-year-old flutist from Pest (also featuring Jenny Lutzer) |

18 April |

Franz Liszt’s charity concert |

In short, the Vienna Liszt arrived at in April 1838 was inundated, one might say, by charity concerts, which were in any case typical at that time of the season and were greatly expanded that year because of the flood. The fact that Liszt gave one (and only one) to help the crisis was not unusual, although that it was his first concert is noteworthy. It was a keen strategic move, but in certain respects he had no other viable option.60 He knew what he was doing—in a letter to d’Agoult five days before the concert he told her: “When you receive these lines I shall already be a consecrated man in Vienna [un homme sauvé à Vienne]” (FLC 313/84).

Liszt left Venice on 7 April and reached Vienna at midnight on Tuesday the tenth. “My arrival is reported in all the newspapers, and if I am not laboring under delusions as big as Mallefille’s fists, I shall create an immense effect. My first concert, for the flood victims, will probably be next Wednesday. In the next forty-eight hours I shall have heard Clara Wieck (who has stayed expressly for me) and also have seen some of the important people again, Metternich, Dietrichstein, et al.” (FLC 311/83). In a letter from the next day, 13 April, he recounts that the event would indeed take place on Wednesday the eighteenth and that it had already been announced.

Liszt initially planned to stay about two weeks, and the various prolongations of the trip created real tensions with d’Agoult.61 Like Paganini and Wieck before him, he kept on adding dates, with Haslinger arranging his appearances and managing most of his affairs during the trip. (Concerts, even by established organizations, were not planned or announced much in advance; the idea of a season schedule was invented considerably later.) Liszt soon encountered some of the city’s cultural power brokers, including the Hungarian Count Thaddeus Amadé, a former patron of his who, Liszt gleefully reported, “does not like Thalberg and is already ablaze with joy when hearing me” (FLC 312/83). He met Count Moritz Dietrichstein, long a prominent force in the musical life of Vienna (and the person to whom Schubert dedicated his “Erlkönig,” op. 1), who is commonly identified as Thalberg’s father from an affair with Baroness von Wetzlar (with whom, incidentally, Liszt and d’Agoult had just spent time in Venice).62

Before appearing in public Liszt played privately for various prominent musicians, including his former teacher Czerny, Mayseder, Merk, Fischhof (who taught piano at the Conservatory), and the Wiecks, who were staying at the same hotel (Zur Stadt Frankfurt). According to many accounts, Liszt held court there. Years later the pianist Heinrich Ehrlich, a student of Thalberg’s and in his teens at the time, recalled that Liszt’s sitting room was “like an army camp in which all sorts and conditions mingled indiscriminately…. He was equally kind to all, but kindest and most bewitching to any young artist in whom he had discovered talent. Was it any wonder that wherever he went he was followed by a swarm of admirers, that he was adored, idolized?”63 Liszt clearly enjoyed a very rich social life. As he put it to d’Agoult: “I have made no friend here, but still have many courtiers. My room is never empty. I am the man à la mode” (FLC 321/89).

Some of the most vivid and informative accounts about Liszt’s activities while in Vienna come from the Wiecks. Later in her life Clara, now Clara Schumann, had become exceedingly negative about Liszt and detested his music. (In 1851, for example, she admitted that he still played like the “devil,” but stated that his compositions were “just too terrible.”)64 Yet their initial Viennese encounter in 1838 was one of considerable mutual admiration. Liszt had wanted to meet the eighteen-year-old for some time already, and was tremendously impressed by her both personally and musically.65 “She is a very simple person, very well brought up,…entirely preoccupied with her art, but nobly and without childishness. She was flabbergasted when she heard me. Her compositions are truly very remarkable, especially for a woman. They have a hundred times more invention and real feeling than all the past and present fantasies of Thalberg” (FLC 313/85). Liszt soon dedicated his Études d’exécution transcendante d’après Paganini to her, and although she did not dedicate a work to him, Robert Schumann did so with his Fantasy in C, op. 17, some months later.

Liszt spent a good amount of time with the Wiecks during the early part of his stay in Vienna; he reported some of their encounters in letters, as did the Wiecks, and mention even appeared in the press. These reports are helpful in that they give an idea of how frequently Liszt performed in private during his time in Vienna. No doubt there were many soirées and occasions about which we know little or nothing. At Fischhof’s, on Wednesday 11 April, the day of his arrival, Liszt played some of his own etudes, as well as etudes by Chopin, preludes and fugues by Mendelssohn originally written for organ, and Schumann’s Fantasiestück at sight. The next day he again played some of his etudes, the Reminiscences of I puritani, and the scherzo from Czerny’s Sonata in A-flat, op. 7.66 The Wiecks’ first reactions are found in Clara’s diary where Friedrich wrote: “We heard Liszt today at [piano-maker] Conrad Graf’s who was sweating as his piano did not survive the great duel—Liszt remained the victor. He cannot be compared with any other player—he is unique. He arouses fear and astonishment and is a very kind and friendly artist. His appearance at the piano is indescribable—he is original.” To which Clara added: “He immerses himself in the piano…. (The Viennese say: he goes under and Clara rises thereby)—[Liszt’s] passion knows no bounds; not infrequently he injures the beauty in that he tears the melody apart and uses the pedal too much, which must make his compositions less comprehensible to the laymen if not to the connoisseurs. He has a great intellect; one can say of him ‘His art is his life.’”

Clara introduced Liszt to some of Schumann’s new compositions and reported on his enthusiastic response, especially to Carnaval.67 On 18 April she played it for him, together with his own fantasy on Pacini’s “I tuoi frequenti palpiti”: “He acted as if he were playing along and moved his whole body convulsively.” Liszt was flattered that she had not only programmed this work at her 21 January concert, but also performed it at soirées and before the empress, “which is an entirely new honor for me” (FLC 313/85). On 19 April at Haslinger’s, Liszt performed Beethoven’s “Archduke” Trio in B-flat, op. 97, together with Mayseder and Merk, and a four-hand version of his Grand Galop chromatique with Clara.68 Friedrich reported:

He plays Clara’s Soirées at sight and how he plays them! If he could rein in his power and his fire—who could match his playing? Thalberg has written the same. And where are the pianos that can produce even half of what he can and wants to do …?

Liszt does not have a nice tone (fingers too thin) and there is little melody in his compositions—yet still full of feeling. In many ways he is the opposite of Henselt—he does not like to play his own compositions.

It is strange that the ages of the four new players: Liszt, Thalberg, Henselt, and Clara—do not even add up to 100. Liszt’s musical powers of comprehension surpass all bounds of imagination.”69

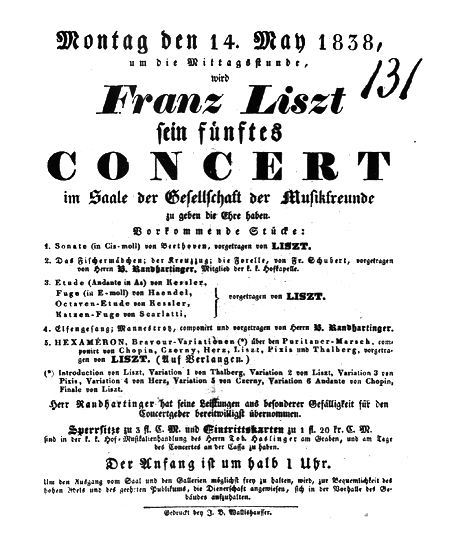

Liszt’s initial encounters with the Wiecks and with prominent Viennese musicians, many of whom had had personal ties to Beethoven and Schubert, convinced him that he was on the right course. He informed d’Agoult that “there was an enthusiasm of which you can have no idea. Without a doubt I am going to have an overwhelming success on Wednesday morning [with the concert for Pest.]” “Best of all,” he reported, he would not have to stay longer than the agreed-upon time, and a second and third concert were already planned that should earn some money (FLC 313/84). The first concert, for the flood victims, occurred at 12:30 P.M. on Wednesday 18 April. (See figure 3.) Liszt reported rapid-fire to d’Agoult later that afternoon: “The post is leaving. Just two words. Enormous success. Cheering. Recalled fifteen to eighteen times. Packed hall. Universal amazement. Th[alberg] hardly exists at present in the memory of the Viennese. I am truly moved. Never have I had such a success, or one that can be compared with it” (FLC 315/86). He used the same phrase about Thalberg being forgotten in a letter to his mother a week later.70 It took but this single experience for Liszt to begin saying that he would like to stay in Vienna awhile: “My thoughts are confused,” he confesses in the same letter to d’Agoult.

On 23 April, just after his second appearance (an evening concert), Liszt opens his letter to d’Agoult: “Forgive me for talking to you once again of my Viennese successes. You know that I am by no means inclined to exaggerate the effect I produce, but here there is a furor, a mania of which you can form no idea. Seats for today’s concert were already sold out by the day before yesterday, and doubtless tomorrow nothing will be left for the third.” He discloses what profits these concerts will bring in, “all expenses paid,” and states that there is no reason not to give more: “I could easily give another half dozen concerts, but want to restrict myself to another two, which will make four in three weeks.” He is pleased that with this money he can live with d’Agoult “in tranquility this summer” and decides not go to Hungary: “What’s the point? You are my homeland, my heaven, and my sole repose” (FLC 318–20/87–89).

Figure 3. Playbill of Franz Liszt’s charity concert for the flood victims of Pest and Ofen on 18 April 1838.

The rest of this essay will examine Liszt’s remaining weeks in Vienna. I shall begin with an overview of his activities drawn from his writings, as well as from those of some with whom he came in contact, and then move on to a more detailed look at his public concerts and their reception. The most immediate information about Liszt’s activities upon his arrival is found in his letters. Those he wrote to d’Agoult (her contemporaneous letters to him for the most part do not survive) typically offer a mixture of giddy excitement and nonchalance, proud reportage and depressed complaints. It is as if, after the initial effusions, Liszt realized he had better check himself and switch to a world-weary tone; he states that he had not “yet made a single interesting acquaintance” (FLC 316/87), proclaims that his “life is prodigiously monotonous” (FLC 327/92), and makes extravagant claims of being miserable without her. His enthusiasm is far more convincing, however, than his professed boredom, especially when placed alongside comments he made to others in which no reservations were expressed. In a letter to Adolphe Nourrit sent soon after leaving Vienna, he praises the city, “where I spent one [sic] of the best months of my life, spoilt, adulated and, better than that, seriously understood and accepted by an outstandingly intelligent public.”71 A private letter that he wrote to Massart at the same time summarizes his activities and accomplishment: “I will not bore you any more with my success in Vienna. In short, seven concerts for my own benefit, the least successful of which, that is to say the first, netted 3500 francs. Three charity concerts, one for the benefit of the flood victims, one for the institute for the blind and the Sisters of Mercy, and another; a concert at Court, for the Empress and Archduchess Sophie (notwithstanding all the small intrigues and cabals at Court). A personal and artistic effect unheard of in Vienna, a popularity always increasing, and the sympathetic esteem and enthusiasm of the crowd, such was the result of my five-week stay in Vienna.”72

Although the surviving correspondence is one-sided, we can surmise that Liszt was under considerable pressure to return to Venice. He constantly needed to reassure d’Agoult that he would be with her soon, and noted that although he was not having much fun, he would at least make money: “That’s the best of it” (FLC 316/87). Money, in fact, is a recurring theme in his correspondence from Vienna (and not just with d’Agoult), the central issue being how much he could make for himself, not how much he might give to charity; indeed, he writes very little about the flood victims or about Hungary. There is no doubt that in Vienna, as throughout his long career, Franz Liszt was an exceedingly generous man and artist, probably unparalleled among musicians of his century, but that generosity need not be exaggerated, as is commonly done regarding this episode in his life. Nor should we underestimate his keen interest at the time in personal gain, especially as he had a mother, mistress, and two children to support. Liszt, who came from humble origins, realized in Vienna that he could make a considerable amount of money—something that was commented upon in the press.73 The most relevant and repeated story from the trip that casts Liszt as unconcerned with mundane pecuniary matters, however, concerns the remark he allegedly made to Princess Metternich, with whom he did not get along, after she asked him how business had been at his concerts in Italy. Liszt famously responded: “I make music, not business.”74 The anecdote immediately made the rounds in Vienna—Clara recounted it in her journal on 6 May—and Liszt would tell it himself for years to come. And yet on one of the occasions when he had to inform d’Agoult that he would be extending his trip, Liszt explains: “I am making absolutely splendid business” (Je fais de très brillantes affaires) (FLC 321/89).75

Liszt’s letters to d’Agoult from mid-April (their number drastically declined in May, or at least do not survive) waver on the issue of whether, when, and how she should come to Vienna herself, or whether they should perhaps meet halfway in Klagenfurt. At one point he sent her money for the trip.76 She then became ill in early May and apparently began complaining about her state of health.77 In any case, a trip to Imperial Vienna was probably not really viable given the illicit nature of her relationship with Liszt, or was simply not something she wanted to endure. Liszt repeatedly professes his great unhappiness and asks himself in the letters why he ever came to Vienna in the first place.78

Fame and fortune may have initially been high priorities for Liszt, but after arriving in Vienna he seems to have become increasingly excited by the musical values and regional sentiments he encountered there.79 Any shift in priorities has been partially obscured by the account he wrote and published months after the trip; the views he expressed therein are rather different from what he stated while in Vienna. This shift is also obscured by well-known comments written many years later in Marie d’Agoult’s memoirs, where she states, “Franz had abandoned me for such small motives! It was not to do a great work, not out of devotion, not out of patriotism, but for salon success, for newspaper glory, for invitations from princesses.”80 According to her account, she was for the first time keenly aware of the difference in their social status and felt the trip had changed him. She says she was devastated by his admission that he had been unfaithful to her: “The way in which he spoke about his stay in Vienna brought me down from the clouds. They had found armorial bearings for him—a republican, living with a grande dame! He wanted me to be heroic. The women had thrown themselves at his head; he was no longer embarrassed over his lapses, he justified them like a philosopher. He spoke of necessities…. He was elegantly dressed; his talk was about nothing but princes; he was secretly pleased with his exploits as Don Juan. One day I said something that hurt him: I called him a Don Juan parvenu.”81

No doubt these colorful comments were critical in convincing later commentators of the significance of the Vienna trip for Liszt’s personal life. Biographers of as different stripes as Ernst Newman and Alan Walker agree on the fundamental significance of his unaccompanied trip. Newman finds that “the decisive moment in their story was Liszt’s departure for Vienna in 1838; though their union was to last, at least in outward form, for another six years, it was already virtually over in inner fact, though neither of them seems to have been fully conscious of this at the time.”82 Walker believes that “the roots” of the couple’s estrangement “can be traced back to Liszt’s departure for Vienna in 1838.”83

The scholar, like a child watching parents divorce, runs the risk of getting caught in the middle and taking sides in what became a nasty, albeit fascinating, breakup. The passage just quoted from d’Agoult’s memoirs may not be accurate, and much of what she says is unbelievable and not supported by documents from the time. Her memoirs are supplemented by some fictional writings to which, as Walker has rightly observed, they often bear a close similarity.84 While her later writings have proven to be eminently quotable, they should not carry the same weight that befits what she actually wrote in 1838, her diary and letters, which relate nothing about problems with Liszt. In correspondence with Ferdinand Hiller, Louis de Ronchaud, and Adolphe Pictet that spring and summer, she mentions him only to pass along his gossip from Vienna and to take some pride in his success there.85 None of Liszt’s surviving letters from Vienna discuss flirtations, romantic conquests, or other women (except for Clara Wieck, a safe subject). In short, d’Agoult’s memoirs and fiction, too often treated as if they were authentic documents from 1838 in uncritical biographies, must be approached with considerable skepticism. At that time her relationship with Liszt was still relatively young. She had recently given birth to their second child, Cosima, and soon after his return would become pregnant again. The bond was not yet doomed, nor had Liszt abandoned Marie.

Liszt’s letters from Vienna focus on his triumphs and money, interspersed with considerations on whether d’Agoult should come and declarations of his love. They are far less rich in detail than the Wiecks’ candid observations about local musical and social life. In his later published account he remarked:

Not a year passes that the Viennese are not visited by two or three renowned artists. I saw Thalberg again there, but he had unfortunately decided not to perform publicly. Kalkbrenner had been announced, but we learned to our great regret that when he arrived in Munich he decided to return to France. I was still in time, however, to meet an interesting young pianist, Mademoiselle Clara Wieck, who had secured a very fine and legitimate success for herself this past winter. Her talent charmed me; she possesses genuine superiority, a true and profound sense of feeling, and she is always high-minded.86

There are a large number of references to Thalberg, whom he calls the “Ostrogoth,” sprinkled throughout the correspondence. The “big news” at the end of April was of his rival’s coming to Vienna and their dining together at Dietrichstein’s on 28 April. “I am very glad about the arrival of the Ostrogoth, for I can now be accommodating with no great effort” (FLC 321/89). He informed his mother that Thalberg “has bought a beautiful horse and often rides in the Prater. Yet he positively refuses to play in private or in public.”87 But from Clara Wieck’s diary we learn that Thalberg had played already. When the Wiecks returned to Vienna from a brief trip to Graz at the end of April, they discovered Thalberg’s arrival: “The competition in Vienna continues,” Friedrich wrote on 6 May. Liszt performed at a charity concert that day, and Thalberg played his Moses fantasy, as well as some etudes at Baron Eduard Tomascheck’s.88 Wieck noted that he apologized for “being out of practice and said he believed that most of the time he plays very well. Today he was embarrassed,” to which Clara added: “Thalberg behaves in a very likable manner and continually requested us not to judge him by today’s performance.”

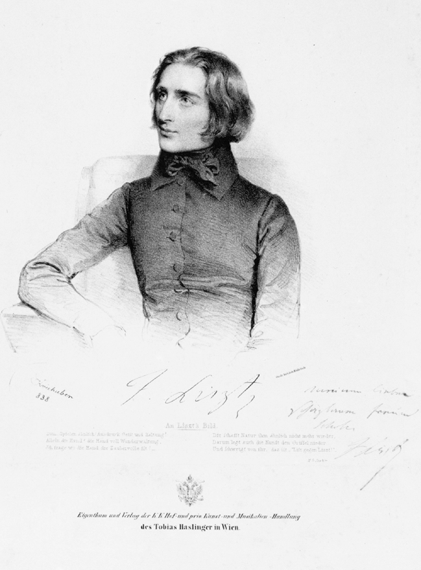

The presence of the three virtuosos was recognized in various ways, such as their becoming honorary members of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde.89 The prominent artist Joseph Kriehuber created lithographs of Thalberg and Liszt, and Staub of Wieck, which were sold to the public.90 (See figures 4a, 4b, and 4c.) Liszt informed Marie: “Fifty copies of my portrait have been sold in a single day.”91

What Liszt most wanted, however, was to be named k. k. Kammervirtuoso. Thalberg had received the honor in 1834 and proudly used the title at home and abroad; it appeared on playbills and on the title pages of some of his compositions. Indeed Liszt made some snide remarks about this in his testy review of Thalberg’s compositions in January 1837, where he implied the honor derived from personal connections rather than from artistic merit.92

Clara Wieck was given the title k. k. Kammervirtuosin in mid-March, the seventh musician to be so honored; she, too, attached the title to programs and publications. As her diary and correspondence make clear, this all had long been in the planning; various negotiations were necessary because she was young, foreign, and Lutheran.93 Friedrich noted on 15 March: “The Kaiser’s patent was presented. I have never paid 7 fl. for a seal and 1 new Austrian ducat with such joy” and he then gave the citation:

To the Piano Virtuoso Clara Wieck, By the Grace of God, In consideration of her outstanding artistic skill and as a public gesture of the highest satisfaction with her artistic accomplishments, His Majesty the Kaiser, has decided with the highest cabinet approval on the 13th of this month to bestow the title of k. k. Kammervirtuosin on her, a decision which this present degree confirms with satisfaction.

Despite Liszt’s disparaging comments about Thalberg, it is clear that he too lobbied for the Imperial title, which now numbered Paganini, Thalberg, and Wieck among the select. At first he apparently thought that Count Amadé could help, but Liszt did not enjoy the imperial support that his competition did, especially Thalberg, and his suit was unsuccessful. This rejection was indicative of what appears to have been rather widespread opposition to Liszt from some in the Court.94 Soon after his arrival he presented himself, but Princess Metternich, “as a matter of etiquette, did not receive me the first time” (FLC 313/84). The diplomat Philipp von Neumann recorded in his diary Liszt’s successful visit soon thereafter: “He astonished us by the self-sufficiency of his manners. He is a product of ‘la jeune France’ beyond anything one can imagine.”95 Performing at Court proved harder to arrange and dates kept on getting postponed. It was a frustration Liszt conveyed to d’Agoult: “I am adulated, cajoled, and feted by everyone, with the exception of half a dozen individuals, rather influential ones for that matter, who are fuming and fretting about my successes. Princess M[etternich] is behaving better toward me than she did in the early days. Thalberg is more to the liking of these people. But they don’t know what to do about it, because of the great mass of people who have come out unanimously in my favor, thereby consigning the Ostrogoth to the second rank. A Viennese bon mot: ‘L…is das Mandl, Th…das Weibl’” (Liszt is the man, Thalberg the woman) (FLC 327/92).

Figure 4a. Lithograph by Staub of Clara Wieck (1838).

Figure 4b. Lithograph by Kriehuber of Sigismond Thalberg (1838).

Figure 4c. Lithograph by Kriehuber of Franz Liszt (1838).

In fact, there was active suspicion about Liszt’s politics and morals. Informing d’Agoult that his Court appearance was postponed, he remarked: “By the strangest chance, you played a part in my lack of favor, the Empress’s devoutness being taken advantage of for the benefit of some childish animosities or other” (FLC 321/89). It was hurtful information that Liszt might better have kept to himself, but it shows there were consequences due to the nature of his personal life. A secret report dated 25 April from Count Josef Sedlnitzky, the powerful chief of police, presents the conclusions of an investigation into Liszt’s background, especially concerning rumors about his alliances with the likes of George Sand and Abbé Lamennais. Sedlnitzky also mentions the elopement with Marie and concludes: “He appears to me indeed as a vain and superficial young man, who affects the eccentric manners of the young French of today, but who is good-natured and, apart from his value as an artist, of no real significance.”96

Although things improved, with members of the Imperial family attending many of his concerts (as duly noted in the press), Liszt played at Court only once. A few days before he wrote Marie: “After all the intrigues, all the cabals which I have told you about, it is a veritable small triumph for me. I don’t need to explain this subject to you. You know me” (FLC 329). The event was on the evening of 17 May, in “the apartments of her Majesty.”97 The next day he wrote to his mother: “Despite all the petty cabals and Court intrigues, I played for the Empress yesterday. The success was complete and my friends extremely pleased.”98 He goes on to tell her that he expects to be appointed k. k. Kammervirtuoso, the honor he mocked, yet desired, and in the end did not obtain.

Summarizing Liszt’s trip soon after he left, the Leipzig Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung reported:

Liszt, after giving a charity concert on behalf of the unfortunate inhabitants of the two neighboring cities, Pest and Ofen, performed six more concerts and one soirée musicale. Each of these netted him on average between 1,600 to 1,800 silver Gulden. He also played twice for the Imperial Court in the private residence and just as many times for charitable causes. He even played to help out a female singer who was passing through. And he performed in the salons of the foremost families of this Imperial city, in the homes of various artists, in the showrooms of the finest instrument makers, as well as at his own lodgings. It is not in the character of this childlike, amiable young man to refuse any request, or behave in a self-important or precious manner. The subtly uttered wish of a true friend of art is all that is required, and he is ready at the piano. He will fantasize at the keyboard for an hour just for one overjoyed listener, without thinking of stopping.99

This account indicates the enormous scope of Liszt’s private and public appearances, and except for mistakenly saying that he played at Court twice rather than once, it helps explain some of the general confusion in the Liszt literature concerning how many public concerts he gave. Because his first appearance was the charity concert, it did not count, so to speak, at least in Liszt’s own enumeration and in the way subsequent concerts were listed on the playbills. This created inconsistencies at the time, in the press, and even in Liszt’s own letters. For example, Liszt wrote to d’Agoult on 8 May: “This morning [was] my fourth concert (which is actually my sixth, although those for the people of Pest and [the 6 May charity concert] in the Redoute don’t count)” (FLC 326/91). His final appearance (25 May) was billed as a “Soirée musicale,” and that meant it figured differently as well.100 As reported, Liszt appeared as the featured artist on two further charity concerts; that of 6 May is the one he mentioned to d’Agoult, which benefited the poor, blind, and elderly, and the other, on 24 May, was for the Sisters of Mercy.101 (See figure 5.) Liszt included these charity concerts in his numbering, which therefore brought the total to ten concerts, still not including an appearance he made at a concert given by the soprano Angelica Lacy in the Augartensaale on 15 May or his playing at Court on 17 May.102 Table 3 below lists Liszt’s public appearances as announced in the playbills and table 6 at the end of the essay gives the complete programs for his principal concerts.103

Figure 5. Playbill of the charity concert for the Sisters of Mercy on 24 May 1838.

Table 3. Liszt’s Appearances in Vienna 1838

18 April |

Charity concert for the Hungarian Flood Victims |

23 April |

First concert |

29 April |

Second concert |

2 May |

Third concert |

6 May |

Charity concert for Versorgungs- und Beschäftigungs-Anstalt für arme erwachsene Blinde |

8 May |

Fourth concert |

14 May |

Fifth concert |

15 May |

Plays at a concert given by soprano Angelica Lacy |

17 May |

Plays at Court |

18 May |

Sixth concert |

24 May |

Charity concert for the Institut der barmherzigen Schwestern |

25 May |

Soirée musicale |

Liszt’s “enormous success,” the concert for the flood victims on 18 April in the Musikverein, was different in certain respects from his following appearances. It being the first, it naturally received the most attention in the press. It was the only one of his principal concerts that used an orchestra. Karl Holz, Beethoven’s close associate in his final years, led the orchestra in Cherubini’s Les Deux Journées overture, followed by Liszt performing Weber’s Konzertstück for piano and orchestra. Although this would become one of Liszt’s warhorses, the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung noted that the work was out of favor at the time, and it was only the brilliance of his performance that helped make a strong case. According to their account: “The thunderous applause knew no bounds; and such a tribute of recognition must have affected the virtuoso deeply, accustomed though he was to homage, for hot tears rolled down his cheeks.”104

Thalberg had offered use of his Erard piano to Liszt for this concert, on which occasion he played two Graf pianos as well.105 Friedrich Wieck observed: “Konzertstück by Weber on Thalberg’s English grand—Puritaner Fantasie on the Conrad Graf—Teufelswalzer and Étude (twice) on a second Graf—all three destroyed but everything full of genius—tremendous applause—the artist informal and kind—everything new and unbelievable—only Liszt.”106 As at most of his concerts, there was a “declamation,” in this instance a poem by the satirist Moritz Saphir (editor of the Humorist) delivered by Julie Rettich, and a Lied, Beethoven’s “Adelaide,” sung by Benedict Gross. He ended with his Valse di bravura and his Grand Etude in G Minor, which had to be repeated, and he was recalled twelve times.107

‘“Reserved seats already sold out!’ This, as all music lovers know, are the most important words on a concert announcement and themselves a powerful verdict on the event itself.” So the Humorist began its review of his next concert, which took place on Monday, 23 April, at 7 P.M. in the presence of the emperor’s mother, her daughter the Archduchess Sophie, and a large assemblage of “musical and literary celebrities.”108 The following five concerts, like the first, were held at 12:30; afternoon concerts were more common than evening ones in Vienna, in part for reasons of lighting and heating. This was not a preplanned series—concerts kept getting added on as Liszt extended his stay. Press reports indicate that they were sold out in advance—with one critic stating that there had never been such a demand for tickets in the history of the Musikverein.109 The ticket prices, 3 florins C. W. for reserved seats and 1.20 for the remainder, were the same as what Wieck and most others charged at the time.110 Over his career Liszt was sometimes accused of overcharging, but that was not the case in Vienna. Because the orchestra was not used and he could sell many more seats, however, the profits were higher.

The exceptionally enthusiastic reception of the initial concerts set the tone for intensive comment in the press, as well as in more personal accounts. Throughout his Vienna stay, the critical response was almost unanimously enthusiastic; there were generally no pro- and anti-Liszt factions or debates over what he did well or poorly, which one sometimes encounters during his career. Much of the reception is fairly interchangeable with what had been expressed, or would be, in other cities before and after. Two years later, after concerts in Dresden, Robert Schumann remarked in a glowing review of a Liszt concert: “All of this has been described a hundred times already, and the Viennese, especially, have tried to catch the eagle in every way: with pitchforks, poems, by pursuit, and with snares. But he must be heard—and also seen; for if Liszt played behind the scenes, a great deal of the poetry of his playing would be lost.”111

In addition to the abundance of criticism issuing from Vienna, its level was also high. Friedrich Wieck remarked on 7 December that “criticism of music here is refined and correct—and judgment made with great intelligence. They are very much interested in true music here and the taste is far better than the reputation.” Liszt seems to have been similarly impressed. While overvaluing comments from writers often bought into the hype, trafficking in gossip and fanning the flames of competition, the detailed reviews of figures like Heinrich Adami of the Allgemeine Theaterzeitung, who went to all of the concerts, provide valuable documentation of the events. Indeed, press accounts are particularly useful for their reportage—we learn what was new and unusual about Liszt in comparison with other performers. From a large amount of public and private commentary, I will concentrate on briefly distilling five issues that often arise: 1) the nature and quality of Liszt’s playing; 2) his repertory; 3) comparisons with other virtuosos; 4) his stage presence and manners; and 5) the phenomenon of Liszt as a celebrity. Most of these factors are interrelated in some way.

Quality. Critics struggled to find the “right words” needed to praise Liszt’s playing.112 Liszt was particularly pleased with two long articles about him, the first by Saphir in the Humorist and the other by Ignaz Kuranda in the Telegraph, and requested separately from d’Agoult and his mother that they arrange to have them translated into French and reprinted.113 Both articles are written in extravagantly poetic language; there are not many details about the events themselves, just effusions about the performer. The Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, which reprinted part of Saphir’s piece (thereby making it quite widely known), called it a better “portrait” of Liszt than Kriehuber’s lithograph. Part of the lengthy article states:

Liszt knows no rule, no form, no law; he creates them all himself! He remains an inexplicable phenomenon, a compound of such heterogeneous, strangely mixed materials, that an analysis would inevitably destroy what leads to the highest charm, the individual enchantment: namely, inscrutable secret of this chemical mixture of coquetry and childlike simplicity, of whimsy and divine nobleness.

After the concert, he stands there like a conqueror on the field of ballet, like a hero in the lists; vanquished pianos lie about him, broken strings flutter as trophies and flags of truce, frightened instruments flee in terror into distant corners, the listeners look at each other in mute astonishment as after a storm from a clear sky, as after thunder and lightening mingled with a shower of blossoms and buds and dazzling rainbows; and he the Prometheus, who creates a form from every note.114

Reading less flowery commentaries one is struck by two common observations that resonate with criticism elsewhere: the orchestral nature of Liszt’s playing and his commanding physical presence. Many conclude that you had to see him to get the full impact and be able to understand the reaction he evoked in his audiences. Most listeners had never experienced anything like it. In contrast to Thalberg’s reserved presence at the keyboard, Liszt’s movements were sometimes considered excessive.

Critics had long remarked on the sheer power of Liszt’s playing, on its orchestral ambitions, and reported that he “defeated” pianos, breaking strings right and left. The Vienna concerts were no different, especially the first concert with its three pianos and broken strings. Pietro Mechetti wrote in the Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst that “many passages in his works suggest that one of his immediate objectives seems to be to turn the piano as much as possible into an orchestra.”115 Upon hearing Liszt’s transcription of Rossini’s overture to William Tell, Saphir commented on how brilliantly he was able to convey all the orchestral sounds on the piano.116 Adami praised Liszt’s “wonderful symphonic handling of the piano.”117

Repertory. The fact that after the Pest charity concert Liszt dispensed with the orchestra for the rest of his concerts changed the nature of the events.118 He appeared in most parts of the program and was onstage far more than was usual. We have seen that Thalberg principally played his own compositions and that in comparison Wieck offered a much wider variety of serious and popular works. Liszt praised the “enlightened eclecticism” of Viennese audiences and satisfied this with the range of the pieces he offered, including chamber music (the Hummel Septet, a piece he performed frequently and would later arrange for piano solo), vocal music, transcriptions, and sonatas; a wide variety of both elevated fare (Beethoven sonatas) and popular (opera fantasies, etudes, and gallops). In total he performed some fifty pieces by eighteen composers, many of them public premieres, all apparently from memory, and only repeating a work from an earlier program as an encore or by request. One such request was for a relatively new addition to his repertory, Hexaméron, a set of “Bravour-Variationen” on a march from Bellini’s I puritani. Liszt wrote the introduction, a variation, some transitions, and finale of this piece, with the other variations contributed by leading pianists of the day: Thalberg, Pixis, Herz, Czerny, and Chopin.119 (See figure 6.) Liszt improvised just once in the public concerts. Rather than encore Weber’s Invitation to the Waltz as the audience wanted on 18 May, he launched into an improvisation based on the piece. According to a report in the Telegraph, an audience member was so taken as to give out a loud cry of enthusiasm, distracting Liszt, who cut his playing short. “The short improvisation had nonetheless given us a deep insight into the inner life of the artist.”120

Figure 6. Playbill of Franz Liszt’s concert on 14 May 1838.

Comparisons. I have already commented that not only critics but also the performers themselves were constantly making comparisons between and among the leading pianists of the day, principally Liszt, Thalberg, and Wieck, as well as Henselt, Bocklet, Chopin, Kalkbrenner, and others. One of the best-known comparisons was written by Joseph Fischhof for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in mid-April, therefore before any of Liszt’s public concerts, but after he heard him play privately. He ranks Liszt, Wieck, Thalberg, and Henselt according to a long array of qualities, including purity of playing (T, W, H, L); improvisation (L, W); feeling and warmth (L, H, W, T); versatility (W, L, T, H); beauty of touch (T, H, W, L), and so forth—even “Egoismus” (L, H) and “no grimacing while playing” (T, W) are considered. He concludes that Liszt is the representative of the French Romantic school, Thalberg of the voluptuous Italian, and Wieck and Henselt of the sentimental German.121

Thalberg, as the hometown favorite, was the pianist typically invoked by the critics. Many reviews of Liszt’s concerts mention him, usually to Liszt’s advantage—Liszt is a genius, Thalberg a talent. An interesting diary by a nineteen-year-old Viennese woman, Therese Walter, an amateur musician whose family hosted musical soirées Liszt attended, gives some idea of how pervasive a topic of conversation this comparison was among concertgoers. Reacting to a poem by Josef Zedlitz that cast Liszt as Byron and Thalberg as Goethe, she remarks that the comparison is apt to a point, especially for Liszt, but that the talented Thalberg is not in the same league as Goethe. The drama between the two pianists, she believes, would make an excellent subject for a play.122

As we have seen, Wieck had recently enjoyed a phenomenal success in Vienna, but Liszt overshadowed her. Adami was the most candid:

I do not want to diminish the accomplishments of this excellent artist, but inadvertently one is reminded that much, or rather all, in art and in life depends on that one lucky moment, and that frequently chance and circumstance determine the degree of one’s reputation. What if that young artist had arrived here after Liszt? What would the outcome of her appearance have been then? This question is easily and without much afterthought answered by those who have heard both perform. In posing it, I sincerely do not want to disavow the acclaim that Clara Wieck has received, or to judge the enthusiasm for her exaggerated, or even laughable. Rather, my intention is to draw attention to the fact that much of a virtuoso’s fortune and reputation depend on the choice of the right moment. Clara Wieck has presented us with superb artistry. Should we begrudge her the laurel wreaths that a public devoted to the beautiful laid at her feet as a sign of grateful remembrance; just because another came along whose genius surpasses hers? Those who think along such lines will just as quickly retract the enthusiasm with which they greeted Liszt as false or inauthentic when another star appears on the artistic horizon. Let us not resent what anyone achieves by talent or genius. The domain of art is inexhaustible. The creative force of the genius is invincible. And even if we consider something today as unsurpassable, we will never be certain that something even more superior may not appear tomorrow!123

Clara seems to have felt similarly. Although she did not perform in Vienna following Liszt’s arrival, she did concertize in Graz soon after hearing him and before returning to Leipzig. She confided in a letter to Schumann: “Once again I survived playing at the theater. The applause was as usual, but my playing seemed so bland and so—I don’t know how to put it—that I almost lost interest in continuing my tour. Ever since I heard and saw Liszt’s bravura, I feel like a beginner.”124 Her father wrote to her mother after Liszt’s first appearance: “It was the most remarkable concert of our lives, and it will not be without lasting influence on Clara. The old schoolmaster will take care that she does not follow his many tricks and eccentricities.”125

Manners. It was not just the way Liszt played, what he played, and how he looked that fascinated audiences—his style and manners were also completely new to them, especially the way he would regularly engage in conversation with the audience, in French generally, and foster such an informal atmosphere. As Dana Gooley has rightly observed, the press generally said little about any Hungarian connection for Liszt, but tended to identify him as French.126 Adami reports that “Liszt appears each time well before the start of the concert and mingles with the public, speaking and conversing with everyone, leading the ladies to their seats, creating space and order, is here, then there, and generally makes himself the host of the hall. All this is completely new for Vienna, one must see it for oneself.”127 Clara noted in her diary on 6 May that while Liszt “is playing in his concerts, he speaks with the ladies sitting around him, always stays with the orchestra, drinks black coffee, and behaves as if he were at home. That pleases everyone now, and he creates a furor. Lenau calls him ‘the greatest musical magician.’ His behavior is totally French and artless.” The Leipzig Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung observed:

Every corner of the hall was packed to the rafters, even the pit which had been cleared and turned into regular seating. It was so full that there was hardly room enough for the artist and his instrument. There he sits then, in the midst of an exclusive circle of ladies, a jewel in the crown, conversing first with the one on his right, then with the one on his left, all with a mix of innocence and the ingratiating charm learned in the world of the Parisian salons. And it is in this mix that his indescribable and unprecedented appeal lies. Even members of the highest aristocracy feel at ease here. We are no longer dealing with a public concert but rather a gathering of guests invited to experience the greatest aesthetic appreciation, an assembly where everyone knows everyone, where the joy of participation sparkles in every eye, and where all are united by the same cause; this shared engagement even succeeds in lessening the differences between classes. But when the master touches the keys once more, the roaring sea calms down. Dead silence returns, as if decreed by powerful Neptune himself.

As we see in this report and many others, the audience itself was notable; the press related for each concert the presence of the highest nobility and of the “artistic nobility of our musical city.”128