Chapter Three: George Jackson and the Black Condition Made Visible

Being born a slave in a captive society and never experiencing any objective basis for expectation had the effect of preparing me for the progressively traumatic misfortunes that lead so many blackmen to the prison gate. I was prepared for prison. It required only minor psychic adjustments.

—GEORGE JACKSON, Soledad Brother (1970)

There was plenty of champagne and good cheer at the book party held outside the gates of San Quentin on October 15, 1970. Friends and colleagues from Berkeley, Oakland, and San Francisco extolled the author. So did the book’s editor, Gregory Armstrong of Bantam Books, who flew out to Marin County from New York City to speak at the celebration. The event organizers gave everyone in attendance a free copy of the book, which soon became a best seller. The only person missing was the author. From his cell, George Jackson, prisoner A63837, could not see the crowd that had gathered to celebrate the publication of his first book, Soledad Brother. Capturing the mood of the event, one of the attendees yelled at the prison gates, “Like Johnny Cash said, ‘San Quentin, I hope you rot; you never did no good.’”1

Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson was and remains the most famous literary expression of black prison radicalism in this period. The book gathered dozens of letters that Jackson had written between 1964 and 1970. Most of the letters were addressed to his parents, while some were to his sisters or his brother, who was only seven years old when George went to prison in 1960 and was dead by the time the book appeared. Except for five introductory letters written in 1970 expressly for the book, the letters were arranged in chronological order beginning in 1964. As Jackson became a known force among leftists, first in California and then across the country and around the world, his list of correspondents grew. Many of the later letters were addressed to his attorney, to his editor, and to a small but growing coterie of female supporters. Because California prisons at the time did not allow prisoner letters to cover more than the front and back of one sheet of paper, most of them were brief, though some were grouped because they had been written within days of each other and to the same person.

Jackson was eighteen when he was sent to prison to serve between one year and life for a petty robbery. Now he was about to turn twenty-nine and a published author. To read Soledad Brother was to track the development of the author’s increasingly radical politics. Indeed, Jackson’s attorney and publisher had arranged the book’s contents to emphasize a political evolution that used prison conditions as an allegory for the black condition overall. They wanted to expose the conditions of confinement in hopes of generating wider antiracist mobilization, echoing the strategy pursued by abolitionists during slavery and antilynching activists after the defeat of Reconstruction. They hoped that exposing the cruelest forms of racism, the most violent and constricting experiences, would motivate people to act against a larger system of racial oppression. As in those earlier movements, prison organizers focused on the wounded yet dignified black, usually male, body, hoping that if people identified with the aggrieved, if they could see that the prison was not a static or impenetrable site, they would realize that the political order itself was simultaneously more brutal and more vulnerable than it was believed to be.

Jackson issued a powerful call to arms: “When we attack the problem with intellectualism [alone] we give away the advantage we have in numbers.” But he also served as a liaison from the prison, informing the world of the political conversations happening in cages and cell blocks. “Growing numbers of blacks are openly passed over when paroles are considered,” Jackson explained. “They have become aware that their only hope lies in resistence [sic]. They have learned that resistence [sic] is actually possible. The holds are beginning to slip away.”2 Jackson offered a stunning rebuke of imprisonment from within. That the book’s title appropriated the name of a prison where Jackson stood accused of killing a prison guard showed an irreverent challenge to the prison system itself, a refusal of the prison’s power to determine social solidarities.

Part of the book’s appeal undoubtedly came from Jackson’s ability to turn the barest conditions of survival into a site of deep personal transformation. In fact, Soledad Brother is perhaps most eloquent in its defense of the life of the mind. Jackson’s letters express the dialectic of imprisoned radical intellectuals, proclaiming a freedom of and through the mind while simultaneously challenging the oppressive weight of racism and confinement as “the closest to being dead that one is likely to experience in this life.”3 To Jackson, the life of the mind was essential to the body’s survival. The allure of George Jackson as both author and organizer lay in his stubborn insistence that the prison was not all-powerful. He trounced the guards and the entire system they represented while providing an existential meditation on freedom. Indeed, Jackson offered his evolving political consciousness as the dividing line between life and death. “I must follow my mind. There is no turning back from awareness. If I were to alter my step now I would always hate myself. I would grow old feeling that I had failed in the obligatory duty that is ours once we become aware. I would die as most of us blacks have died over the last few centuries, without having lived.”4

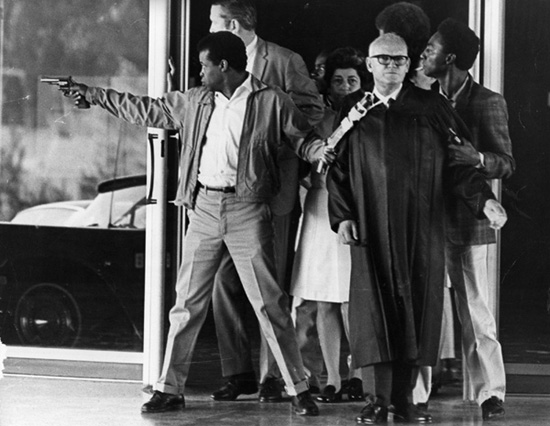

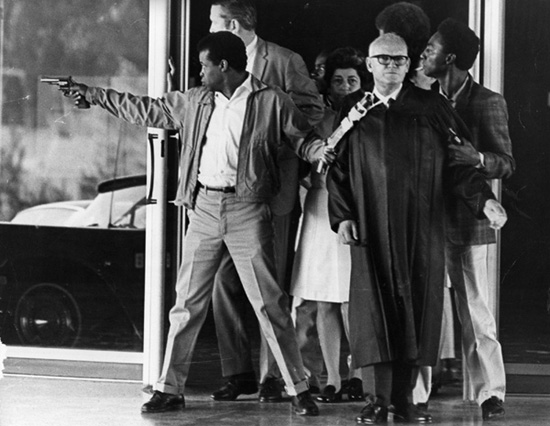

The book was just one side of making visible the prison as a site of black racial and political formation. Indeed, the book release party’s large crowd and media interest arose from more than the novelty of the location at the front of the prison, the strength of the marketing campaign, and the prepublication buzz around an eloquent book that had been serialized in the New York Review of Books. It arose from years of organizing by prisoners, complemented by greater attention from outside radical groups to the prison and punctuated by a stunning act of violence. On August 7, 1970, five weeks before the Soledad Brother release party, George Jackson’s younger brother, Jonathan, stormed the Marin County Courthouse with a satchel full of guns during a trial of a San Quentin prisoner. The seventeen-year-old Jackson armed three prisoners, and the group took five hostages, among them the judge and district attorney. San Quentin guards and area police opened fire on the group, killing Jackson and two of the prisoners along with the judge. It was a tragic and gruesome incident, and it foreshadowed George Jackson’s death at the hands of prison guards one year and two weeks later.

The Jackson brothers’ actions, literary and military alike, took place in the middle of a massive wave of prison riots, with a reported fifteen such incidents in 1968 and at least forty-eight in 1972, the most of any year in U.S. history up to that point (and the actual number of disturbances was likely quite higher).5 These riots were joined by a spike in prisoner assaults on guards as well as guard attacks on prisoners.

The culture of American prisons was changing. While prison is an inherently tumultuous place, rebellions and attacks had a more explicitly political character in the late 1960s and early 1970s than at most other moments in American history. This political character could be found both in the intent of such disturbances as well as in their reception: prison-based rebellion captured the radical imagination during these years. The Black Power and New Left movements gathered energy from news of prison unrest, and prisoners imbibed the ideas and culture of the political movements outside—and now inside—the prison walls. Influencing many activists and artists on the street, prisoner radicalism was most inspirational to other prisoners, who responded most frequently and most militantly to prisoner writings or uprisings with more writings and more uprisings. Dissident prisoners at varying institutions recognized a common project in the tumult facing 1970s prisons: the struggle for survival was embedded in a makeshift campaign against the brutality of confinement and criminalization.

Jackson emerged as a translator of the discontent that had been growing inside prisons. He was part of a generation of black prisoners who challenged racism in prison and whose politics were shaped by the extrajudicial killing of black prisoners by white guards or white prisoners, often acting with the collusion of guards. Jackson exposed the contentious and violent struggles behind prison walls. His words provided a coherent narrative through which people could understand rising prison protest. In Jackson’s urgent telling, prisons were schools, rapidly graduating dedicated revolutionaries who transformed themselves behind bars: “There are still some blacks here who consider themselves criminals—but not many. Believe me, my friend, with the time and incentive that these brothers have to read, study, and think, you will find no class or category more aware, more embittered, desperate, or dedicated to the ultimate remedy—revolution. The most dedicated, the best of our kind—you’ll find them in the Folsoms, San Quentins, and Soledads. They live like there was no tomorrow. And for most of them there isn’t.”6

Jackson’s description of the polarized prison environment was also an argument about the broader constrictions that structure black life. To be black, Jackson claimed in a prescient analysis of the carceral state, was to live in and struggle against confinement. Black politics required “improvising on reality” from within what Jackson elsewhere called “the Black contingencies of Amerika.”7

The prison’s social significance emerged from this combination of eloquence and violence, vision and action. Prison organizing utilized what could be called a strategy of visibility. Prisoners and their allies reasoned that if the prison’s power lay in its invisibility, its ability to remove people from view and access, thereby subjecting them to untold and untellable forms of violence, then exposure constituted a means of resistance. Visibility ran counter to the prison’s mission and, they hoped, ability to function on a daily level. Their tactics, ranging from the pen to the sword, were designed to spread dissident views and nurture popular revolt against the status quo. This strategy generated a series of political linkages, connecting the inside to the outside while creating space for alliances among revolutionaries, progressives, and moderates. The stark conditions of confinement, in other words, drew the attention of a wide cross-section of society interested in the human rights demands coming from American prisons.

Prisoners’ struggle over basic conditions of life called into question the system that sustained such massive vulnerabilities. Liberal reformers and militant revolutionists thus met at the prison walls, with a shared motivation to expose the horrors transpiring within—horrors that tarnished the veneer of racial innocence outside the South, especially in California. Making the racism of imprisonment visible undermined the assumption that northern states generally and California in particular were somehow immune to such violence.8

This emphasis on visibility was, for revolutionaries such as George Jackson, articulated through prevailing Marxist ideologies developed especially through the Third World revolutions of China, Algeria, and Cuba. In each, persistent armed struggle served as a rallying cry through which colonized populations garnered popular support. For many who grew up poor and subject to routine state violence in this age of revolution, these countries provided powerful examples of Goliath’s long-awaited defeat. Viewing the rigidly hierarchical and racially violent world of the prison as an extension of the colonial world, prison organizers deployed a similar combination of intensive action and active iconicity. These prisoners made visible a black condition shaped by their highly masculinist surroundings; they operated within the sex-segregated world of the prison and defined their success through the scale of disruption.

George Jackson became the symbolic and global figurehead of a political and intellectual movement located in American prisons. He was charismatic and intelligent, strong and soft-spoken. He had a way with words, bestowing nicknames on his friends and romantic sobriquets on his love interests—and more important, situating imprisonment within a sharp political economic critique that was self-consciously steeped in black intellectual life. He had a keen ability to distill complex ideas into relatable, accessible terms. He was, according to many who knew him, easy to talk to and quick with a smile, at least among friends. To them, he was generous with his time, knowledge, and what little resources he had available to him. He delighted in sharing his prodigious knowledge with anyone who would listen as well as in using it to advance his ideas about prisons, economics, and military strategy. He taught interested fellow prisoners Marxism and martial arts: how to fight back intellectually as well as physically.9 He retained a hard edge among competitors and antagonists, and like anyone, he could be vicious when he wanted to be. But his eloquence, intellect, and political commitments propelled his popularity within and beyond the California prison system.

A wide-ranging thinker steeped in the black radical tradition, he patterned himself after a series of heroic warriors—from slave rebels such as Nat Turner to anticolonial theorist Frantz Fanon to folk heroes like Stagolee, “the lawbreaking, woman-chasing, gambling man” who had long populated black outlaw ballads and had been revived as an icon among 1960s black nationalists.10 Jackson’s hypermasculinity overemphasized his authoritarianism, overshadowing some of the traits that made him the most radical: his collectivity, his mentorship, his fierce intellect and passion for change. Indeed, one unfortunate by-product of Jackson’s macho posturing—an example of prison’s exaggerated masculinity—is the way that it obscured the cooperative, nurturing elements of his praxis, including giving the proceeds of his writings to his comrades in prison and in the Black Panther Party. He viewed his notoriety as bound up with a collective politics; in turn, he sought to give back to that collective.

The frenzied period that saw Jackson move from dissident prisoner to celebrated author and from global revolutionary icon to one of six people killed on San Quentin’s bloodiest day resulted from competing claims about who he was. As historian Rebecca Hill notes, Jackson tested “the left’s ability to trust Black men, to believe in imperfect heroes, and to define itself without the long-standing and comfortable logic of white rebellion and Black victimization.”11 Indeed, Jackson’s life and death in the partial spotlight, as well as his death’s continuing reverberations in prison politics throughout the decade and beyond, tested not just the Left but American society at large. The story of George Jackson is a story of cross-cutting narratives in which both Jackson the person and Soledad Brother the book were distinct figures among a large cast of characters. Jackson was caught between the story he wished to tell about himself not just in books but in actions and the stories that publishers, journalists, activists—and a long list of antagonists—wished to tell about him. For all of these actors, Jackson’s story was a microcosm of the black condition itself.

Only by situating Jackson within these different narratives and their wider historical context can we make sense of who he was and what he did. At a different moment, Jackson would never have gotten a book contract, and his ideas never would have caught the attention of millions of people worldwide. He never would have been seen as a beacon of revolutionary humanity or emerged as a global icon of black radicalism without fifteen consistent years of black activism passing through prison gates. But in 1970, the Black Panthers were Public Enemy No. 1, Richard Nixon was expanding the war in Southeast Asia he had promised to end, and the prison became a powerful site in which to make sense of America’s enduring racial hierarchies in the early years of formal equality before the law.

“WITHOUT HAVING LIVED”

George Lester Jackson was the second oldest of five children and the oldest son of Lester Jackson, a postal employee, and Georgia Jackson, a homemaker. His parents were from southern Illinois, although like many black people who moved to Chicago in the interwar years, they traced their roots to the South. Lester and Georgia married in Chicago’s West Side ghetto. Georgia gave birth to their first child, Delora, in 1940. George came fifteen months later, on September 23, 1941. Over the next twelve years, three more children followed: Frances, Penelope, and Jonathan. The Jacksons were like many black families during World War II and its aftermath: hardworking and nominally race conscious but not politically involved. Georgia introduced her children to the writings of black scholars and novelists but does not appear to have belonged to any political organizations.12

Their experience was typical in another way: like many teenage boys, George—or George Lester, as the family liked to call him—began to get in trouble.13 Indeed, the Jackson family had moved from Chicago to Los Angeles in 1956 in the hopes that the new environment would put young George on a different path. But he continued to run afoul of the law, and police arrested him three times in 1957 for attempted petty burglary. On one of those occasions, officers shot the sixteen-year-old Jackson in the forearm and leg. He spent eighteen months in a reform school for boys before being paroled at the end of 1958. He completed his sophomore year of high school under the tutelage of the California Youth Authority, the state’s juvenile justice system, which loomed large over the lives of poor black migrants to the Golden State. Upon his release from the reform school, Jackson continued to court danger amid the hyperpolicing of the ghetto. Four more arrests for fighting and robbery followed, and he served another few months under the authority’s auspices.

On September 18, 1960, five days before his nineteenth birthday, Jackson was on his way back to Pasadena from Tijuana with a friend when they held up a gas station, netting seventy-one dollars. Jackson was the getaway driver, but in light of his prior offenses, his court-appointed attorney convinced him to plead guilty in exchange for leniency. The judge, taken more with Jackson’s record than with his plea, sentenced him to serve between one year and life in prison. The vagueness of Jackson’s prison term, his “indeterminate sentence” of one year to life, was a hallmark of California’s ostensibly liberal penal policy. It became the most controversial aspect of Jackson’s eleven years in prison. Rather than assigning a fixed range of years as punishment, indeterminate sentencing meant that the parole board, the Adult Authority (or, for those in juvenile detention, the Juvenile Authority), would examine each prisoner’s application on a case-by-case basis to see if the person met the standards for release. California’s indeterminate sentencing law was passed in 1917 but gained steam as a model of social engineering during World War II. The law effectively made the parole board, not the judge or jury, the sentencing body; it alone decided when and under what criteria people had proven themselves sufficiently “reformed” to be released.

What made California’s prison system liberal was its architects’ belief that the state would remove wayward individuals from society in order to remake them into proper citizen-subjects. Rightlessness was supposed to be temporary and transformative. Critics charged that the Adult Authority used prison time as a bludgeon to ensure compliance with the prison rules and a self-discipline modeled on a bourgeois Western work ethic. Prisoners critiqued the idea of “rehabilitation” as meaning little more than being obsequious to the prison’s authority—and with it, the injustices that continued to characterize the American state.14

Jackson entered a California prison system in the wake of transition, with the contradictions of its liberal prison governance producing more turmoil within the institutions. Four months before Jackson’s imprisonment in 1960, the state had executed Caryl Chessman, a man serving time for rape and robbery who had written four best-selling books while incarcerated.

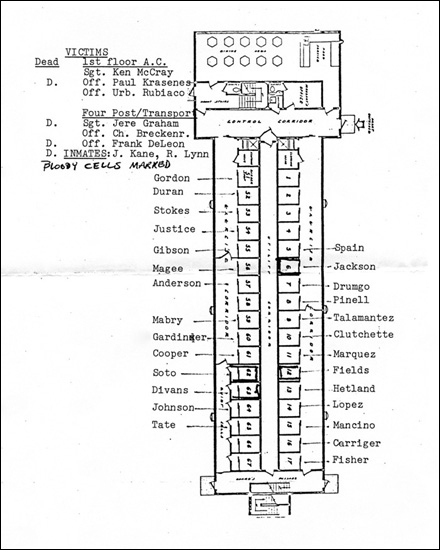

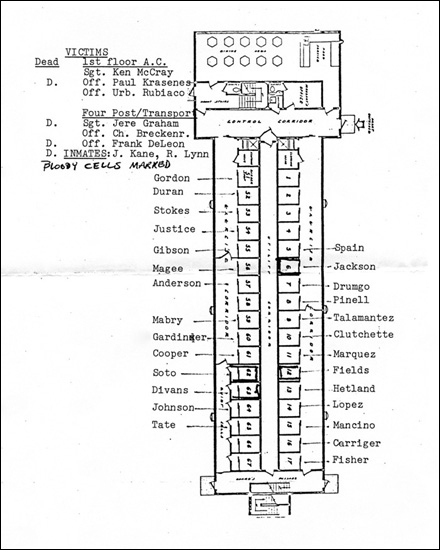

That year also saw the state open a solitary confinement unit at San Quentin known as the “Adjustment Center” (AC). The name bespoke the coercive model of rehabilitation touted by California prison officials in the postwar years, involving medicalized attempts to “correct” deviant individuals.15 Life inside the AC was a mixture of routine violence and structural boredom. Prisoners spent twenty-three or twenty-four hours a day locked in their dimly lit cells, with limited human contact, time outside, or access to programming and showers. San Quentin’s AC consisted of three tiers, with seventeen cells on either side of the floor separated by an alley that was not accessible to foot traffic. The top floor was reserved for death row prisoners, while the second floor held prisoners who were in protective custody. The bottom floor of this prison within a prison held up to thirty-four prisoners whom the guards deemed the most incorrigible. Almost all of the men in the cells on the ground floor of the AC were black and Latino, and several of them knew each other from other prisons or from other units of the prison. The men could yell to the people in adjoining cells but could not see or visit with them. Within the AC, prisoners were largely hidden even from other prisoners.16

Jackson began his sentence at Soledad Correctional Training Facility, a prison twenty-five miles southeast of Salinas in California’s Central Valley. The Soledad prison had opened in 1951, surrounded by the vineyards of the Salinas Valley. Jackson spent eleven years going back and forth largely between Soledad and San Quentin, disaffectedly called “the Q” and located in Marin County, less than twenty miles from Berkeley, Oakland, and San Francisco. Unlike Soledad, the modern prison in rural farmland, San Quentin was an archaic dungeon near San Rafael Bay. It had been built by convict labor in 1852, two years after California became a state and the U.S. Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which committed national resources to maintaining slavery through policing black mobility. It was the oldest prison in California and soon became one of the most famous prisons in the world.17

Upon entering prison in 1960, Jackson inhabited a world even more sharply polarized by race than the neighborhoods he had once called home. The few sanctioned social spaces inside the prison were segregated, and white prisoners and guards regularly attacked black prisoners. Jackson’s response became one of collective self-defense. In 1962, he gathered a few other black prisoners to avenge the racially motivated stabbing of another black prisoner; guards foiled the plot with guns and gas and then shipped Jackson and his coconspirators to San Quentin. It was the first of several write-ups Jackson received, and each reprimand took him further from the possibility of parole.

Journalist Min Yee reported that between “1962 and 1970, Jackson was cited forty-seven times for disciplinary infractions. He was denied parole ten times, even though his crime partner in the gas station robbery had been released years before.” Most of his infractions “were for minor matters—playing poker, grabbing more food from the chow line when he was hungry,” having more cigarettes in his possession than were allowed, failing to line up at the bars during count or to clean his cell. While some of these infractions resulted only in reprimands, he was often placed in solitary as punishment. Between 1965 and 1969, he received three citations for fighting and two for possessing weapons; all of the other incidents involved nonviolent activities that constituted small acts of protest against the picayune protocols of prison life.18

Jackson displayed a strong political consciousness throughout his incarceration, emphasizing self-defense and self-determination. His involvement in the prison’s illicit economy, where food and cigarettes were currency, was rooted in an ethic of solidarity that took an increasingly radical political tone. He dreamed of autonomy, telling friends as early as 1962 that he wanted to create his own forms of governance on an island somewhere. He organized a food strike at the Deuel Vocational Institution in 1962 and continued to explore a wide variety of tactics, strategies, theories, and philosophies. The year he went to prison, seventeen countries in Africa won their independence, and he saw the work of revolutionary movements there as having a direct bearing on the issues he personally faced.

Conditions in California prisons were atrocious: rancid food, limited programming, segregated facilities, limited access to basic hygienic measures, arbitrary and extended solitary confinement. Black and politically active prisoners suffered even more than others, aware that they faced constant threats of violence from white prisoners and guards in addition to the restrictions that racial segregation already placed on them. Many prison officials not only nurtured racism but demanded absolute obedience to their authority, no matter how capricious their demands.

As Jackson’s politics grew more radical, he participated in clandestine study groups reading Marxist classics and contemporary works, from Lenin and Trotsky to Fanon and Mao. He introduced many prisoners to these and other thinkers and led political education sessions in the San Quentin yard about racism and political economy. Jackson began to discuss socialism, constantly referring to people as “comrades” and earning himself the nickname “the Comrade.” (Even that moniker was educational, since some prisoners unfamiliar with the word initially thought Jackson wanted to be called “Conrad.”) Jackson convinced skeptical black and Latino prisoners that socialism was relevant to their lives.19

Jackson was part of a wider circle of mostly black radicals looking to end structural violence and the ways it manifested through interpersonal racist attacks. In this context, prison organizing was a matter of urgency and delicacy. On the one hand, black (and many Latino) prisoners needed to defend themselves against racist assault. On the other hand, as long as prisoners of different racial groups remained antagonistic, institutional conditions would not change. Jackson took the lead among a group of black prisoners in attempting to break the stalemate: he emphasized the importance of prisoner unity against guards. He imagined this united front in successive waves, allowing black prisoners to defend themselves against white prisoners’ attacks while working toward greater unity among all prisoners premised on a shared rejection of the prison state. He preached the same message to activists on the outside: “I know I am black. I know that no one can better represent his blackness than I. I can and have always represented mine. . . . If a man wants to relate to my blackness, fine, but I would prefer he relate to me on the basis of my status as a soldier in the WORLD revolution.”20

Part of developing such multiracial unity in prison required breaking the guards’ monopoly on the use of force. Only they had arms, and they had complete license to beat or kill prisoners. Jackson was one of many prisoners who thought that prisoners should defend themselves by striking back, by responding in kind when guards killed prisoners.21

By the mid-1960s, with California’s overall prison population declining, Jackson had gained notoriety throughout the California penal system.22 His reputation spread by word of mouth and the transfers of friends and associates to other prisons. A network of black radicalism existed across the state penal system as people were transferred from the California Youth Authority to prison and from prison to prison, with organizations such as the Nation of Islam, the Black Panthers, and US facilitating its spread.

When Black Panther cofounder and minister of defense Huey P. Newton went to prison in 1968 for the manslaughter of police officer John Frey, he recognized Jackson’s influence in the actions of other black prisoners. Although Newton and Jackson never met face-to-face, they communicated through a growing network of supporters and mutual friends (including Los Angeles Black Panther Geronimo Pratt). Jackson, after all, was to the prison environment what Newton was to the urban one: a minister of defense, a self-taught theoretician, a strident black revolutionary nationalist and Marxist. The two men had a lot to offer each other in helping circulate the message of black revolution between the cell block and the city block. Newton connected Jackson to Fay Stender, a young attorney who was working for Black Panther lead counsel Charles Garry at the time and who went on to found the Prison Law Project. Newton asked Garry and Stender to look into Jackson’s case in 1969 after the Panther leader heard from other prisoners about this man they considered a living legend.

Stuck in a prison cell, Jackson corresponded with his growing list of supporters. He wrote periodically for the Black Panther newspaper and joined the Black Panther Party, receiving the military rank of field marshal. He was charged with expanding the party’s paramilitary apparatus by recruiting members from the prison’s ranks. Many Panthers celebrated the move as extending the party’s reach more formally inside of prisons, since Jackson’s involvement would increase the organization’s profile among those it considered prime recruits. In practice, this designation institutionalized what Jackson was already doing and continued to do; indeed, he routinely boasted that his primary political role was of a military nature.23

Jackson’s deepening connections with the party emerged in tandem with his growing commitment to Third World revolutionary struggles. His membership, as much symbolic as substantive, extended the BPP’s emphasis on prisons beyond the arrests and trials of its Free World members. A series of deadly incidents inside the California prison system in early 1970, part of a simmering war between prisoners and guards, pushed Jackson beyond the pages of the Black Panther newspaper and made him into a global icon of black militancy.

“NO ONE ELSE COULD HAVE DONE IT”

At Soledad, 1970 began with a series of killings. Tensions between black prisoners and white prisoners and white guards had been rising for some time. In early January, W. L. Nolen warned his parents that he felt that the guards were trying to kill him. Arrested for robbery in 1963, Nolen was a prison boxing champ and proto–black nationalist who had tutored several prisoners at Soledad as he had earlier at San Quentin and Folsom. He and Jackson met in 1966 and became fast friends. Nolen filed several lawsuits protesting the threats against his life by white prisoners and the guards’ manipulation of racial tensions at Soledad, but the situation had worsened by the beginning of 1970. Nolen was in a wing of Soledad that had been locked down since the 1968 killing of two black prisoners. Because one of the men, Clarence Causey, had been stabbed on the prison yard, guards closed the integrated exercise yard. Yet they also continued to stoke tensions between black and white prisoners.

On January 13, Soledad guards reopened the exercise yard and let fifteen prisoners access it for the first time in more than a year. The group included eight white prisoners, among them Billie “Buzzard” Harris, leader of the Aryan Brotherhood, and seven black prisoners, including Nolen. When the prisoners, pent up for so long, began a fistfight, Soledad guard Opie G. Miller began firing without warning from the gun tower overlooking the yard. Miller was a twenty-year army veteran and expert marksman; he shot Nolen first, then Cleveland Edwards, who went to help the injured Nolen, and finally Alvin “Jug” Miller. The three men, all of them black and all of them outspoken militants, were shot in the chest and left lying in the yard for twenty minutes before being removed. All three died that night. Only one of the white prisoners involved in the fight was injured, hit by a ricocheting bullet. Many prisoners and subsequent outside observers (including a 1975 jury in a wrongful death suit brought by the families of the dead) viewed the killings as a set-up.24

Black prisoners responded with action, going “on hunger strikes, burn[ing] prison furniture and dispatch[ing] a voluminous amount of mail to their families and attorneys and to state officials, demanding an investigation.” The prison was in an open state of rebellion. “Fistfights erupted in numerous housing wings,” journalist Min Yee reported not long afterward. “White and black cons alike walked around with magazines stuffed in their shirts to blunt knife attacks.” Three days later, in an interview that prisoners heard on the radio, the district attorney said that he believed that the deaths constituted “justifiable homicide.” Some prisoners concluded that the law would offer them no recourse. That night, twenty-six-year-old guard John Mills, a new member of the Soledad staff, was beaten and thrown to his death off the third tier. Several prisoners initially clapped and cheered, but after about ninety seconds, they became stone quiet, fearing what was to come.25

The investigation into Mills’s death quickly focused on Jackson, leading many observers to believe that the authorities had focused on him because of his political beliefs and organizing efforts. While some later accounts claim that Jackson privately admitted to killing Mills, the investigation was so sloppy that one analyst contended that Jackson was framed for a crime he actually committed.26 The Soledad warden summarized the official view of the twenty-eight-year-old Jackson. Without pointing to any evidence, the warden prejudged Jackson’s guilt by saying that “no one else could have done it.”27

All prisoners on the Y wing of Soledad were held incommunicado for two weeks following Mills’s death as guards repeatedly questioned 138 people. Guards plied some prisoners with good food and promises of early release in exchange for their testimony. Others were less fortunate. Captain Charles Moody, feared and hated by many prisoners, put his personal pistol to the heads of some prisoners to elicit statements. There was no independent investigation, save what the prisoners’ attorneys did subsequent to the indictment.

Prison officials focused on Jackson and two others known by their Afro hairstyles and the posters they displayed in their cells to be sympathetic to Black Power. Twenty-four-year-old John Clutchette; Fleeta Drumgo, age twenty-three; and Jackson were held in isolation without contact with the outside world, for another twenty-one days. Clutchette had been in prison for four years at that point, Drumgo for five. Both men were serving time for burglary and expected to get out soon; Clutchette was just forty-five days away from parole. Prison authorities never alerted the men’s families of the charges they faced, and when the mothers of Clutchette and Drumgo called the prison, officials told them that they had nothing to worry about and that their sons did not need legal representation.28

Like Jackson and thousands of other young black men at this time, Clutchette and Drumgo had long records filled with minor crimes—fighting, petty theft, parole violations—that dated back to when they were fourteen and eight, respectively. The three men, who barely knew each other, were formally charged with the murder on February 23, 1970. Three days later, in an incident that demonstrated Jackson’s point about the impunity with which guards committed violence, San Quentin guards beat a mentally unstable black prisoner, Fred Billingslea, and left him in a tear-gas-filled cell until he died.29 Neither youth nor mental illness offered protection from the racism of the American criminal justice system.30

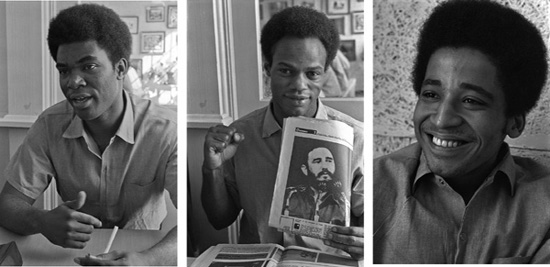

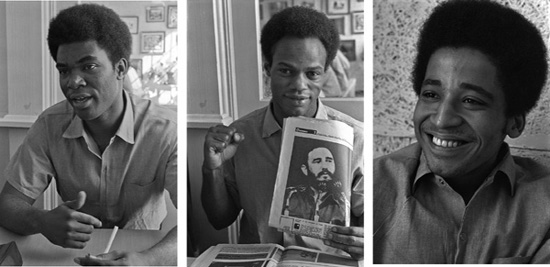

The Soledad Brothers, ca. 1971. John Clutchette, Fleeta Drumgo, and George Jackson were charged in the January 1970 death of a Soledad prison guard. At twenty-eight, Jackson was the oldest of the group and became the most famous. Clutchette was twenty-four and Drumgo was twenty-three when the three were charged in the case. Photo © 2014 Stephen Shames/Polaris Images.

The case attracted local media attention as well as the interest of the Bay Area Left. Stender and the Black Panthers quickly dubbed the three defendants the Soledad Brothers, and the case became paradigmatic of prison militancy throughout the decade, with George Jackson at the center. Jackson emerged as the pivotal figure for multiple reasons. Most immediately, the stakes were highest for him. The California Penal Code mandated an automatic death sentence for a prisoner who was convicted of assault while serving a life sentence. Because Jackson’s open-ended sentence included the possibility of life in prison, he now faced death. Just as important to his fame, however, were his charisma, his extensive knowledge, and his commanding vocabulary. Camera-shy and less well read than Jackson, Clutchette and Drumgo were happy to have him represent the group. A veteran of the system with the eloquence to describe the injustices to which he had been subjected, Jackson was a natural spokesperson for the growing critique of American prisons as a bulwark of racial and class domination.31

Stender became Jackson’s attorney shortly after the three men were charged with Mills’s death. Stender was a hardworking, dedicated, and tenacious radical approaching age forty when she met Jackson. A Berkeley native, Stender had worked for several years with Black Panthers and other Bay Area activists. She took up the case with urgency and discipline, as much a political organizer as a legal professional. She and her associates spent months interviewing more than one hundred prisoners to challenge the government’s version of Mills’s death. She recruited law students to help her with the research and solicited money from the Black Panthers’ growing political defense funds.32

Fay Stender at a protest for George Jackson at the gates of San Quentin, October 1970. Stender was Jackson’s attorney and had previously worked on Huey P. Newton’s case. It was her idea to turn Jackson’s letters into a book, and she later founded the Prison Law Project. Photo © 2014 Ilka Hartmann.

Stender’s legal thoroughness was matched by her knack for publicity. Working alongside Charles Garry on Panther cases, Stender had learned that successful defense campaigns marshaled public attention. She needed her clients to be in the public eye and to have sympathetic narratives. She asked KPFA journalist Elsa Knight Thompson to interview the Soledad warden, helping cement an interest in prison conditions and prisoner cases at the progressive radio station that would last for several years.33 Stender organized her friends and associates to pay attention to the case, incorporating it into the daily rhythm of Bay Area radical communities. In April 1970, she visited Soledad prison with a small delegation that included Senator Mervyn Dymally, California’s first black state senator, in hopes of getting elected officials to support prisoner grievances. She had already pulled together a coalition of black activists, white leftists, and celebrities to launch the first Soledad Brothers Defense Committee (SBDC). Stender fashioned a long list of endorsers for the committee. Carleton Goodlett, a physician and publisher of San Francisco’s black newspaper, the Sun Reporter, who had a storied career in civil rights politics, was among the defense committee’s initial endorsers and later chaired the legal committee.

Other early sponsors included a wide range of figures from the liberal to radical Left, including progressive politicians (Julian Bond, George Brown, Ron Dellums), intellectuals (Noam Chomsky, St. Clair Drake, Martin Duberman), artists (Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Jane Fonda, Maxwell Geismar, Allen Ginsberg, Pete Seeger), attorneys (Arthur Kinoy, William Kunstler, Gerry Lefcourt, Leonard Weinglass), professionals (the Reverend George Baber, Dr. Benjamin Spock, the Reverend Cecil Williams), and activists (Angela Davis, Corky Gonzales, Tom Hayden, Huey P. Newton, Mario Savio).34 The California legislature’s five-member Black Caucus was also instrumental in building early support for the Soledad Brothers. Several prisoners and their family members had contacted members of the caucus to request they investigate conditions at Soledad prison, prompting the legislators, led by Dymally and assemblyman John J. Miller, to visit the prison and meet with the warden in the summer of 1970. While the tour had broader goals, the Soledad Brothers case cast a shadow over the facility. Indeed, seven prisoners were disciplined in June 1970 for trying to raise money for the Soledad Brothers Defense Fund.35

As with other U.S. political defense campaigns, the support for the Soledad Brothers united public figures, who could lend their celebrity to the cause, with family members of the accused, who provided credibility.36 Although George Jackson had a strained relationship with his parents—his father had written a summer 1965 letter to the prison warden opposing his son’s release, and George often blamed his mother for his predicament—his mother and siblings played key roles in the defense campaign. The committee hoped to do more than free the Soledad Brothers; it sought to put the California prison system itself on trial. Writing to Spock as part of her efforts initiating what would become the SBDC, journalist Jessica Mitford argued that “because of what will be exposed about this [case], and what it says about prisons in general (Calif. prisons are, as you know, considered the most ‘advanced’ and ‘reformed’ in the country) I believe the case has national importance.”37 News of the case spread, and other chapters of the defense committee formed, fueled in part by personal connections to the men on trial. The mothers of Clutchette and Drumgo joined Jackson’s family in the defense effort.

So did black members of the Communist Party (CP) chapter in Los Angeles. One of them, Kendra Alexander, had known John Clutchette and his brother, Gregory, who was also imprisoned at Soledad, since junior high school.38 The city now had a substantial and activist black population, and it became an important base of support for the Soledad Brothers. The Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panthers had brought together several formerly incarcerated people and former gang members, making it one of the truest examples of the Panthers’ plan to “organize the brothers on the block.” The chapter had also been plagued by police informants and devastated by tragedy, including the murders of chapter leaders Alprentice Bunchy Carter and John Huggins in January 1969 and the police assault on the party headquarters the following December, as well as running feuds with police and members of the US organization, a cultural nationalist group hostile to the BPP. Los Angeles was also home to the Che-Lumumba Club, an all-black chapter of the Communist Party. Established in 1967, the club was one expression of how the party’s long but checkered history of support for black radicalism joined with the autonomous militancy of the newly pronounced Black Power movement.39

The Reverend Cecil Williams speaks at a rally to support the Soledad Brothers, ca. 1970. Williams was the pastor at Glide Memorial Church in San Francisco. He was a strong supporter of the Black Panther Party and other progressive organizations at the time. Photo © 2014 Stephen Shames/Polaris Images.

The club’s members included not only Kendra Alexander and her husband, Franklin, but also a young graduate student, Angela Davis. Born and raised in Birmingham, Alabama, and educated in New York City, Boston, and Frankfurt, Davis was seasoned beyond her years. She had attended a leftist high school and pursued graduate studies with Marxist theorist Herbert Marcuse, leaving Davis well acquainted with Marxism generally and the CP specifically. She joined the party through the Che-Lumumba Club in 1968, when she was an assistant professor at UCLA, teaching classes on philosophy and liberation there and at a Los Angeles freedom school established by the local SNCC chapter. In July 1969, FBI agent William Divale, who had infiltrated the CP, revealed to the UCLA student newspaper that there was a Communist Party member on the faculty. The article set off a firestorm once Ed Montgomery of the conservative San Francisco Examiner revealed Davis to be the person in question. Montgomery led the ranks of those demanding that UCLA fire her. The newspaper article, printed as Republican governor Ronald Reagan bullied many of the state’s social movements, sparked a fierce battle over Davis’s future in the University of California system. With a daily barrage of hate mail, much of it threatening violence, Davis purchased several guns for self-defense.40

In the winter of 1970, as she fought to preserve her academic career and protect her personal safety, she also began corresponding with George Jackson after reading newspaper coverage of the case. The pair quickly established a rapport, and their correspondence took on a more intimate tone. “My memory fails me when I search in the past for an encounter w/ a human being as strong as beautiful as you,” she closed a June 1970 letter to him. “Something in you has managed to smash thru the fortress I long ago erected around my soul. I wonder what it is. I’m very glad. I love you.”41 Davis became one of the leading members of the SBDC, setting up the Los Angeles chapter in April. She also became close with Jonathan Jackson, George’s younger brother, who looked up to Davis as his teacher and ultimately looked out for her as her bodyguard.

The Soledad Brothers case, with its Manichaean combination of official brutality and attractive, articulate dissidents, encapsulated the prison’s growing centrality in American society. The effort to free Jackson, Drumgo, and Clutchette joined long-standing critiques of legal bias with Black Power militancy.42 The case launched a new wave of prisoner defense campaigns; in the coming years, several prison riots captured national attention and catalyzed a variety of organizations dedicated to reforming or abolishing the prison. For several years after the Soledad Brothers case, writes historian Regina Kunzel, “leftist credibility seemed to depend on radical prison activism”; radical sectors of the feminist and lesbian and gay movements as well as other social movements of the 1970s turned their attention to the prison following the lead of the Black Panthers and New Leftists who made the Soledad Brothers into a cause célèbre.43

The Soledad Brothers case also became a valuable prism through which to make sense of the growing connection between race and incarceration. In 1970, the rate of imprisonment nationally was the lowest it had been in twenty years, with 96 of every 100,000 people in prison. At the same time, however, racial disparities among those incarcerated were becoming entrenched. By 1970, black people were being sent to prison at seven times the rate for whites. In 1944, California’s prison population was 17 percent black, a figure that increased to 28 percent by 1969; the state’s incarceration rate jumped a dramatic 505 percent over the same span. In 1971, the state imprisoned just under 23,000 people.44 After a massive prison-building boom that began ten years later and would ultimately see 1 in 100 Americans incarcerated, California’s prison population topped 150,000 people in prison by 2011.45

When Father Earl Neil eulogized George Jackson in August 1971 as an apostle of “the black condition,” the Episcopal priest was more prophetic than perhaps he realized.46 Writing shortly before the hyperincarceration of poor black men from the inner city became a defining feature of American urban policy, Jackson was both an eloquent writer whose books contributed to making the prison visible and a militant revolutionist whose politics were forged through the racialized brutalities of confinement. He was the primary strategist and tactician of a national prison movement. Jackson advocated violent struggle against any and all manifestations of American power; such a course, he maintained, would cleanse the black soul of the confinement of white supremacy. An American Frantz Fanon, Jackson claimed that violence would vindicate a wounded black manhood and hobble the prison system. Instead, the state increased its capacity for violence. Jackson provided a glimpse of what was to come: an upside-down world where the prison would serve as a palimpsest of the ghetto, an institution that cast a long and indelible shadow over black urban life for the rest of the twentieth century and beyond.47

“A BLACK REVOLUTIONARY MENTALITY”

The idea to turn Jackson’s letters into a book came from Stender, Jackson’s attorney of record, who was inspired by the success of Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice and aware of attorney Beverly Axelrod’s role in it. Stender saw in Jackson’s eloquence an opportunity to both challenge the prison system and build support for her client. She drew on a wider circle of Panther supporters to develop the project from an idea into a publishable manuscript.

Stender contacted her friend Mitford, an enigmatic former communist from a British aristocratic family who had become a celebrated author and muckraking journalist. Mitford, who had been involved through the Communist Party in several efforts to support black prisoners in the 1930s and 1940s, was more than just politically sympathetic; she was also well connected. Mitford introduced Stender to Gregory Armstrong of Bantam Books, securing the support of a major publisher.48 Stender also seized every opportunity to show Jackson’s letters to friends and fellow activists to enlist their support in the nascent SBDC. She gave people the hard sell as well as the soft, casually sharing Jackson’s letters with people over dinner to get them involved by showcasing his passionate writings, at once sophisticated and alluring.49

As the book neared publication, Stender asked for help from French author and Black Panther supporter Jean Genet. (She also sent his play, The Blacks, to the Soledad Brothers.) Genet had built a close relationship with the Black Panthers through two trips to the United States—first in 1968 to cover the Democratic National Convention, when he entered the country illegally through Canada after being denied a visa, and then in 1970 to give lectures and raise funds for the Panthers. Genet wrote the introduction to Soledad Brother, praising the book for displaying “the miracle of truth itself, the naked truth completely exposed.”50 Working with Ellen Wright, Richard Wright’s widow and a literary agent in Paris, Genet helped arrange for the French release of Soledad Brother by his publisher, Gallimard. Genet also solicited the support of several prominent French authors and intellectuals, among them Jean-Paul Sartre, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida, who called for Jackson’s release and were influenced by his work.51

Genet’s contribution to Soledad Brother gave the book an instant, international literary imprimatur. As a world-renowned playwright, reclusive yet extroverted, a former prisoner and a sophisticated analyst of identity, outlawry, and the vicissitudes of publicity, Genet exhibited many of the same characteristics that made Jackson so compelling. Having deserted the army and served time in prison for petty thievery before winning his freedom through his powerful writings, Genet embodied the outlaw image that had captivated the American imagination. Capturing the sexual ethos of outlawry, Genet described being gay as an outlaw sexuality, quieting many homophobic fears among the Left, notwithstanding Jackson’s derision of prison homosexuality in Soledad Brother.

Extrapolating from Jackson’s writings, Genet described prison and death as two sites of black redemption.52 Like Jackson, Genet argued that prisons concentrated the racism of the American state. “One might say that racism is in its pure state [in prison], gathering its forces, pulsing with power, ready to spring.”53 As with many positive appraisals of Soledad Brother, Genet found the book striking for its ability to develop a structural critique through unique and emotionally revealing language. Genet described language as the first and last recourse available to black radicalism, enabling dissent to corrupt the “enemy’s language . . . so skillfully that the white men are caught in his trap. To accept it in all its richness, to increase that richness still further, and to suffuse it with all his obsessions and all his hatred of the white man.”54

Soledad Brother offered a compelling if fractured portrait of life in prison. The book’s fragmentary conversations—only Jackson’s letters appear—offer an atypical glimpse of black masculine common sense in the second half of the 1960s. Indeed, part of the book’s appeal was in its ability for readers to see Jackson as a kind of everyman: a victim of his circumstance, working to make the best of a bad situation. His letters displayed an increasingly militant consciousness that paralleled the radicalization of black urban youth. In the words of New York Black Panther Sundiata Acoli, Jackson was “the epitome of any black person” who elected activism over apathy.55 His letters narrate the major events of the era—the Watts uprising, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the constant rhythms of war and police violence—while subtly displaying the shift from a Nation of Islam–style nationalism to the growing influence of Third World–nationalist Marxism.

Restrictions on the length of prisoners’ letters imposed a unique structure on Jackson’s book. Political arguments come largely in staccato bursts that are bookended by lengthy letters (likely snuck out through mail to his lawyers). In Soledad Brother, Jackson becomes educated in Marxist economics and black radicalism and seeks to share his newfound knowledge with the members of his family. Short letters describing his repeated parole denials testify to the crushing weight of prison. Jackson writes to his younger brother as if for a large audience, projecting an image of mental and physical strength. “You’re supposed to be representing me, meaning that you are to be strong, intellectual, watchful, serious, unapproachable,” he tells Jonathan, then a junior at Blair High School in Pasadena, California.56 (Jonathan, however, objected to George’s frequent discussions of his young age: “It is very hard for me to command authority from anyone if he knows that I am 17,” he complained to George.)57

Jackson intimated that the prison had hardened him and prepared him for battle. His enduring message was one of action against the forces of injustice. “I’ve been patient,” Jackson wrote to his parents in 1965, “but where I’m concerned patience has its limits. Take it too far, and it’s cowardice.”58 Jackson’s sweeping, emotive language reveals an all-or-nothing revolutionary will that prides itself on being both raw and detached. “I can still smile now, after ten years of blocking knife thrusts and pick handles, of anticipating and [sic] faceless sadistic pigs, reacting for ten years, seven of them in Solitary. I can still smile sometimes, but by the time this thing is over I may not be a nice person. And I just lit my seventy-seventh cigarette of this 21-hour day. I’m going to lay down for two or three hours, perhaps I’ll sleep.”59

Jackson almost celebrates the perfection of emotional control that prison has inculcated in him. “So, if they would reach me now, across my many barricades, it must be with a bullet and it must be final.”60 This theme of survival through a mixture of emotional detachment and passionate engagement as a survival mechanism appears in several of Jackson’s letters, both published and not. In an unpublished letter to Mitford, he wrote, “I make my appeal to arms, and the people who have escaped the mindless, yankee autonaton [sic] syndrome. . . . Dispassionately I face the men who hate us—and the real revolution will start here.”61 This emotional discipline went alongside Jackson’s call for guerrilla warfare. He juxtaposed a harsh notion of revolution against anything he saw as sentimental methods for effecting social change. He privately described both sex and armed struggle as “the end-game,” his missions in life.62

Soledad Brother merged memoir and Marxism to develop a theory of imprisonment as an extension of slavery. He often wrote of the deep memory of enslavement and the Middle Passage as foundations of the contemporary world system. “I recall the day I was born, the first day of my generation,” he wrote in one such passage. “It was during the second (and most destructive) capitalist world war for colonial privilege, early on a rainy Wednesday morning, late September, Chicago.”63 The blend of systemic critique with personal detail, the cross-currents of world historical and autobiographical knowledge, has become a standard of prison literature owing in part to Jackson. It suggests the prison was a gestational site of long black memory.64 Jackson’s move between slavery and incarceration provided a racial framework through which to understand both the history and future of disproportionate black incarceration. “Blackmen born in the U.S. and fortunate enough to live past the age of eighteen are conditioned to accept the inevitability of prison. For most of us, it simply looms as the next phase in a sequence of humiliations,” Jackson wrote by way of introduction to the book.65

Jackson’s commentary on black America offered both a retrospective on the recent past and a window into an emerging racial future. That Jackson launched his critique of American society from prison was especially meaningful, for Soledad Brother—and the wider genre of prisoner literature that exploded in the mid-1960s—constituted a metacommentary on the growth and racialized expansion of the carceral state from the viewpoint of its victims. Writing from the shadows of society, in the wake of civil rights legislative victories, George Jackson was a voice of protest for a new generation. He spoke for those who were disenfranchised more by the globalizing corporate capitalism of racial liberalism—increasingly deterritorialized and speaking the language of color-blind inclusion—than by the white-sheeted terrorists of Jim Crow’s fading regime.

In describing the intense violence of prison racism, Soledad Brother stubbornly insisted on the ongoing significance of race to American society. By documenting the persistence of racial hierarchies, Jackson also presaged their changing shape. Anticipating the nuanced investigations of critical race theory, Jackson showed that race persisted in and through otherwise invisible institutions. Indeed, he contended that race and racism remained central to the idea and routine functioning of the United States, regardless of whether they appeared on the public agenda. That he wrote from California’s isolation cells offered a sneak peak inside what was fast becoming a premier technology of racial violence—the prison—while simultaneously illuminating a wider, enduring truth about racialization: racism persists as a material force despite and because of attempts to manage racial difference through a mixture of incorporation and repression.

At the same time, Jackson’s antiracist critique revealed the increasing significance of the gendered fault lines accompanying this seismic shift in the American racial landscape. Simply put, he was the product not only of a Cold War patriarchal culture but of the sex-segregated institution in which he came of age. His masculinist appeals revealed the carceral future awaiting millions of black men while appealing to the notion of restorative patriarchy common to black nationalist groups that recruited inside prisons during the early 1960s, most centrally the Nation of Islam. His radical critique of American political economy did not obfuscate his own allegiance to a conservative, patriarchal notion of respectability.

Jackson’s letters mirror the national moral panic over the state of the black family that had accompanied the 1965 Moynihan Report’s claims that the allegedly matriarchal structure of black families was responsible for black poverty. Jackson’s perspective, while evolving throughout the book, remains fundamentally conservative on gender. “I must be the first to admit that I see that the black family unit is in ruins. It is our first and basic weakness,” he wrote, suggesting that black communities needed to restore the heteronormative family structure that chattel slavery had interrupted. Mimicking the worst elements of the pathological descriptions of black life, common both to the NOI and to wider popular culture, Jackson lambasts the “matriarchal subsociety” that has “always” characterized black America and that has its roots in the sexual violence of slave society.66

Jackson personalized this critique for his own family. In several passages, he argues for the restoration of black patriarchy as key to progress, both for black people in general and for his parents in particular. Indeed, the bulk of Jackson’s letters in the book were written to either his mother or his father (though never to both at once). He laments their individual weaknesses, sometimes blaming them for his predicament, at other moments seeing them as exemplars of larger black failings that could only be corrected through a return to manliness and its authority. He challenges both his parents for allowing Georgia Jackson to dominate the household but also tries to protect them from one another and from his predicament. “Comfort Mom as well as you can and tell her I’m all right, healthy, happy, content,” he told his father on March 26, 1967. “Of course, this is a lie, but she likes to be lied to.”67 In later letters, however, Jackson described his father as the more egregious example of false consciousness, unwittingly believing in the ideologies that repressed him. Indeed, the letters reveal that Jackson clearly saw his race-conscious mother as a sharper political thinker than his father.68

Though directed to his family, Jackson’s concerns seemed universal. Jackson’s eloquence reflected his wide reading in the sciences, economics, languages, philosophy, and anthropology.69 His literary talents expressed an abiding internationalism that he introduced to others as much through subtle word choices as through explicit arguments about the Third World. Jackson’s signature sign-off, “from Dachau with love,” as well as his deliberate use of “U.S.A.” to refer interchangeably to the United States of America and the Union of South Africa as white supremacist states, expressed a global critique of the violence inherent in racial states across time and space, whether the United States, Nazi Germany, or apartheid South Africa. Further, his comparative genocide approach emphasized a radical internationalism. That Jackson introduced many of his readers to the historical existence of the Nazi concentration camps or the brutal policies oppressing black South Africans demonstrated the prison’s inability to contain his intellect or empathy.70 This global vision influenced other prisoners, too. Jackson looked to the national liberation struggles in continental Africa as his greatest inspiration and encouraged others to look to the Third World for examples.71

His charisma blended romance and politics into a life-or-death struggle against all manner of violence and alienation. “If we can reach each other through all of this, fences, fear, concrete, steel, barbed wire, guns, then history will commend us for a great victory won. If so—it will be your generosity and my good fortune.”72 Such language prompted one reviewer to celebrate that Soledad Brother “breathes you in,” showcasing the despair of isolation alongside the redemptive hope of human connection.73 Jackson’s growing ability to channel an existential angst through a communist analysis popularized an antiracist critique of capitalism. “I don’t want to die and leave a few sad songs and a hump in the ground as my only monument,” he wrote of his vision. “I want to leave a world that is liberated from trash, pollution, racism, poverty, nation-states, nation-state wars and armies, from bigotry, parochialism, a thousand different brands of untruth, and licentious usurious economics. . . . If there is any basis for a belief in the universality of man then we will find it in this struggle against the enemy of all mankind.”74

Jackson wrote in his own voice but was steeped in the classics of black literature. He self-consciously followed the tradition of black radical authorship. In a New York Times interview with Mitford, Jackson spoke of reading Richard Wright and W. E. B. Du Bois as a child at his mother’s urging.75 When Jackson wrote, “I’m part of a righteous people who anger slowly, but rage undamned,” he echoed the protagonist of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man—one of the books Jackson had in his cell. (In Ellison’s version, the invisible man exhorts a crowd protesting an eviction in Harlem by describing blacks as a “law-abiding people and a slow-to-anger people.”) And Jackson’s repeated refrain that “we die too easily” recalls a Du Boisian race consciousness first displayed in his classic Souls of Black Folk.76

Soledad Brother sounded similar themes to traditional uplift narratives: it valorized self-education as a necessary ingredient for racial progress, defining progress in terms of both individual responsibility and social change. In Jackson’s hands, the redemptive power of education took a decidedly revolutionary (if sometimes dystopian) turn. The book shattered the idea, embedded in rehabilitative penology, that complacency accrues with time spent in a cage. Instead of making Jackson more docile and palatable, prolonged punishment made him more radical and militant. Paradoxically, the evolution chronicled in Soledad Brother validated the idea that prisons could transform “the criminal mentality,” albeit into a revolutionary rather than an acquiescent citizen.77 (His distaste for neat conversion stories and uplift narratives may be part of what Jackson objected to about the book’s arrangement of his letters and the exclusion of his more military-oriented tracts.)78 Yet the personal transformation Jackson demonstrated fundamentally opposed the prison regime. Jackson described the goal of his political community of prisoners as “attempt[ing] to transform the black criminal mentality into a black revolutionary mentality. As a result each of us has been subjected to years of the most vicious reactionary violence by the state. Our mortality rate is almost what you would expect to find in a history of Dachau.”79

By the time Soledad Brother appeared, Jackson had been in prison for ten years, seven of them in solitary confinement, mostly at San Quentin. By November 1970, with his new book getting rave reviews, Jackson was assigned permanently to the San Quentin isolation unit after an altercation with an officer. Jackson adopted an intensive regimen to train his body and mind, all the more important once he was relegated to permanent solitary confinement. He exercised for hours a day, ultimately boasting of doing one thousand finger push-ups, and spent forty-five minutes a day studying vocabulary. His public statements demonstrated both his erudition and his physical agility. Indeed, his frequent references to physical activity revealed a thinly veiled sexual energy. Jackson’s writings contained a flirtatious streak, and his sexual appeal became part of his political appeal.80

His prominence as a leading figure of not just prison organizing but radicalism more generally made him, in his day and ever since, the litmus test for politicized black male prisoners in an era of expanded carceral capacity. Jackson’s political work, captured in writing and expressed through his collaborations with others in various prisons, encouraged prisoners to see themselves as political actors despite and because of their confinement. He nurtured a collective self-confidence, rooted in a masculine sense of racial pride. His ideas and his orientation nurtured a generation of prison protest. Jackson was both a product of the era’s black militancy and a catalyst for its continued circulation. He synthesized ideas, debates, and strategies circulating widely among a growing coterie of black radicals confined in American prisons. Jackson was a partisan of armed struggle who believed that only retaliatory attacks on guards would stop them from killing prisoners, yet he also advocated both prisoner unity and larger prisoner-focused unity among the Left. As a result, he united people of diverse ideologies around the figure of the prisoner. The cohort congregating around Jackson reversed the defeatist sentiment of imprisonment. Instead of minimal conditions suited to barely sustain life, they developed express political purpose at the margins; out of near-death came political life.

As a result, prison officials treated Jackson’s literary success with the same hostility with which they greeted the publication of Caryl Chessman and Eldridge Cleaver’s respective books. The Golden State proved disinterested in following the bibliotherapy model, an idea dating back to 1947 that reading and writing would prove rehabilitative if prisoners turned that therapy into political critique. “Treatment-era bibliotherapy and the free reading and writing policies accompanying it had produced an ungovernable monster in the opinion of the prison administration,” writes historian Eric Cummins.81 The state’s unwillingness to see prison authors as anything but political threats opened the prison system to critique that it was as brutal and repressive as these authors maintained. As an author, Jackson displayed a maturity of thought that demonstrated his intellectual development since his teenage days of petty criminality. That he continued to be denied parole and face constant threats from prison authorities seemed to prove the system’s ideological basis. To Jackson’s growing base of supporters, his ongoing incarceration betrayed the injustice of the prison system and the larger political order that sustained it.

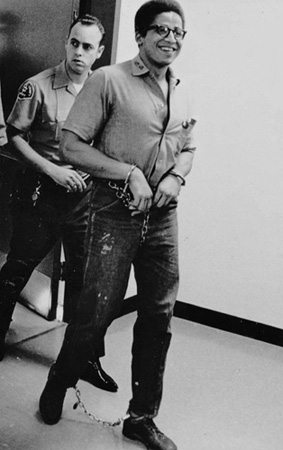

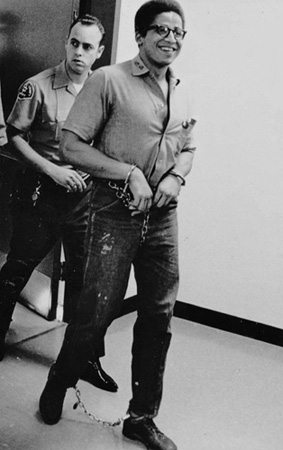

George Jackson being led to court, ca. 1971. The cuffs around his wrists are shackled to his waist and connected to the cuffs at his ankles. Jackson had been known throughout the California prison system as a theorist and a militant years before he became known to the larger public. As he became famous, many supporters celebrated his humor and charm alongside his revolutionary politics. Photo by Dan O’Neil; courtesy of It’s about Time Black Panther Archive.

Soledad Brother became an instant classic of black protest literature. The success and popularity of Soledad Brother put Jackson’s work on par with the other urtexts and masculine antiheroes that had characterized the Black Power days: he was the literary heir apparent to Malcolm X and Eldridge Cleaver. He saw himself in that political tradition, while journalists and other observers saw him in that literary tradition. The parallels are not hard to spot. For all three men, the prison served as a point of politicization. Incarceration marked their point of conversion from petty criminal to political radical. Their respective books—The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Soul on Ice, and Soledad Brother—narrated this conversion, establishing the prison as a pivotal institution of black radical self-making. Each successive text emphasized the prison more than the last. For Malcolm, prison is the turning point. Cleaver’s book anthologizes essays written during his incarceration but not published until he had been paroled and become a leading figure in the Black Panther Party.82 Jackson, however, remained in prison, and his redemption did not lead to his release, as it did for Cleaver and Malcolm. Jackson’s redemption lay in the fact that he was, as several reviewers put it, “free” behind bars: he retained his ideas and his convictions and through them his voice. Whereas Cleaver and Malcolm showed that radical politics could come out of prison, Jackson demonstrated that radical politics could develop and sustain themselves behind bars.

Even more than these earlier books, Soledad Brother revealed that political critique, indeed political thought itself, could travel from inside prison to the outside world, not just the other way around. Coming alongside growing interest in the plight of prisoners from the New Left, this capacity for intellectual critique was, in fact, the source of the prison establishment’s anxiety about prison authors. “To San Quentin administrators, local citizen involvement in prison issues seemed so potentially violent in the early 1970s that the prison prepared for a ‘storming of the Bastille’ and drew up plans to close access roads to the prison and even to direct prison tower gunfire outward, for the first time in history, onto any group attempting to break into the prison.”83 Beating a hasty retreat from bibliotherapy, officials also worked to ban Soledad Brother from entering California prisons (a practice that continues in the early twenty-first century). Several California prisons refused to accept copies of the book that the publisher donated to their libraries. Word of the book still spread, and individual prisoners received copies. Jackson told the New York Times that prisoners “seem to be gratified that one of us had the opportunity to express himself” and appreciated that he was “getting ideas across, speaking for them, speaking for us.”84

While they did not want other prisoners to read the book, prison officials viewed the text as a chance to conduct surveillance on prison militants and thereby undercut their efforts to mobilize. Soledad Brother provided the rationale for officials to curtail prisoner efforts to communicate with the outside world. L. H. Fudge, the superintendent of a northern California prison, released a memo to state prison officials suggesting that “every employee in the Department of Corrections” read Soledad Brother to help them understand “the personality makeup of a highly dangerous sociopath.”85 San Quentin warden Louis Nelson justified closing or restructuring several educational organizations in the prison by pointing to media coverage describing the prison as “the best breeding and/or recruiting ground for neo-revolutionaries.”86

Critics, however, celebrated Jackson as the latest prophet of black rage. The New York Times’s “Selected Books of the Year in Nonfiction” awkwardly praised Soledad Brother as “a document of revolutionary rage, ‘the most important single volume from a black since The Autobiography of Malcolm X.’”87 In a review titled “Beyond Cleaver,” the Washington Monthly said that Jackson “picks up where Cleaver left off.” But, the reviewer argued, Soledad Brother did more than that: it was more “inclusive” and universal than Soul on Ice. “Where Cleaver throws you back on yourself because you are not black, not oppressed—and that has its value—Jackson draws you in through your shared humanity.”88

This shared humanity became part of the marketing campaign, with Bantam Books inviting readers to identify with Jackson and his family. The paperback edition of the book carried a quotation from Huey P. Newton proclaiming Jackson the “greatest writer of us all” and praising the letters as a message to a larger national “family”: “Because of his burning need to communicate with his family, Jackson finally communicates with everyone.” The book received the Black Academy of the Arts’s nonfiction award and was named one of the American Library Association’s Notable Books of 1970.89 Reviews in British periodicals described Jackson as a “free black man in white America,” attempting to obliterate “ghettos of the mind.” Jackson had “lost his freedom—and found himself.”90 Soledad Brother was so popular that Mitford joked that “literary agents are scouting prisons for convict talent.”91 With great repression came great wisdom. Pointing to Malcolm X and George Jackson, one prison activist argued that “contemporary prison rebels have provided some of the best insights into American society.”92 For another decade, prisoners authored widely received books, poems, magazine articles, plays, and more as Black Power influences seeped into American television and cinema.93

These reviews of Soledad Brother fit with Stender’s hope that the book would help build support for Jackson and the other Soledad Brothers. She and Armstrong attempted to manage Jackson’s image as an icon around whom black protest might cohere. At the release party for Soledad Brother at the gates of San Quentin, Armstrong called Jackson “a medium, a voice for all oppressed people.”94 Armstrong and Stender sought to portray Jackson as the symbol for an individual and collective search for justice, even as Jackson himself seemed to prefer an image more heroic and less sentimental. When Julius Lester wrote at the end of his favorable New York Times review of the book that Jackson “makes Eldridge Cleaver look like a song and dance man on the Ed Sullivan Show,”95 Armstrong wrote several letters chastising the Times for possibly damaging Jackson’s relationship with the Black Panthers. Armstrong argued that the newspaper had an obligation to print a rejoinder from Jackson for the benefit of the Soledad Brothers defense campaign and its relationship with the Black Panthers.96 The public narrative of Jackson rested on presenting black militants as a united force; the cocreators of his image objected to reviews that undermined this presentation. Jackson’s response to the Times called Cleaver a “master” political theorist and demanded that “any comparison between myself and Comrade Cleaver must be respectful, or it doesn’t represent my feelings of fraternity and love for him.”97