Chapter Four: The Pedagogy of the Prison

This monster—the monster they’ve engendered in me will return to torment its maker, from the grave, the pit, the profoundest pit. Hurl me into the next existence, the descent into hell won’t turn me. I’ll crawl back to dog his trail forever.

—GEORGE JACKSON, Soledad Brother (1970)

His parents named him Luis Talamantez, but everyone called him Bato, a Mexican Spanish colloquialism for a respected man, a comrade. He had been in and out of California state institutions since the age of twelve. In 1965, Los Angeles Superior Court judge Joseph Wapner (the same Judge Wapner who later became famous on the television show The People’s Court) sentenced the twenty-three-year-old Talamantez to two five-year-to-life sentences stemming from two robberies that netted him $130. No one was hurt in either incident, but Wapner appeared to want to make an example out of Talamantez, much as an earlier judge had given George Jackson a similarly lengthy sentence after a similarly petty robbery. During his years inside, Talamantez earned a reputation for being principled and creative. He wrote poetry and read books about ancient history. Talamantez was one of a few Latinos who associated with black prisoners at San Quentin, working to end hostilities between the two groups. That and other efforts earned him the enmity of several guards and a few prisoners, and on several occasions, he had to fend off attacks. So it was that he found himself in the Adjustment Center on August 21, 1971.1

Like most of the men in the AC that day, Talamantez left his cell when Jackson forced the guards to open the doors. Curious and cocky—Jackson had nicknamed him “Machismo”—Talamantez joined the majority of AC prisoners in wandering the tier for the chaotic half hour during which they were out of their cells. He was in the foyer of the unit, near the door leading out to the yard, when Jackson went outside. There had been an “eerie quiet” before Jackson exited the building. Though Jackson said nothing, Talamantez thought he had a look that asked, “Is anyone coming with me?”2 Sundiata Tate seemed to want to follow Jackson, but Talamantez held him back. The only thing waiting for them in the yard was a giant wall.

Just one prisoner, Johnny Spain, followed Jackson into the yard. The other men assembled in the foyer—Talamantez, Tate, Louie Lopez, Hugo Pinell—did not move. They were disoriented and in shock. Then they saw the guards set up on the balcony rail gun post above them and heard the gunshots above the blaring escape siren. Through the open doorway, Tate saw Jackson go down.3 At that point, knowing that many more officers were on their way down to the tier, the twenty-odd prisoners who had been out of their cells since Jackson took over the AC ran to the other end of the floor and barricaded themselves inside four of the strip cells. These cells were Spartan, even for the AC: they had no toilet, just a hole in the floor. Talamantez was in a cell with at least four other men, gripping the iron door to hold it closed against the impending rush of the guards. In the cell next to them, David Johnson sat with Pinell, Tate, and Ruchell Magee, convinced they were all about to be killed. Though he did not smoke, Johnson asked Tate for a final cigarette.4

The guards came into the unit and fired a burst from a machine gun. Then they called out the names of the guards who had gone missing. They first called out for “Ruby,” AC officer Urbano Rubiaco, who, still bleeding from cuts to his throat, ran into his coworkers’ arms. Removed from the unit, Rubiaco demanded a gun so that he could go kill the prisoners in the AC.5 Once the guards had custody of Rubiaco and the other two surviving officers, Charles Breckenridge and Kenneth McCray, they called out for the best known of the remaining prisoners in the AC. “Magee! Come on out with your hands up! Walk backwards naked,” they yelled to Ruchell Magee, the only surviving participant from Jonathan Jackson’s August 7 raid and a prodigious writ writer well versed in protesting prison conditions. The guards repeated that instruction for each prisoner by name, one by one.

Walking to the guards in the foyer gave the prisoners a chilling feeling: they knew they would be beaten and chained, but they also knew they had no other choice. “One at a time, they did us like that,” Talamantez recalled. “They grabbed us. Made us all come out naked. Walk backwards, too. It was very traumatic at the time. We were all scared to death. And you could just see, these guards wanted to kill us so bad.”6 As each prisoner reached the row of guards at the end of the tier, he was hit and thrown into the courtyard outside the AC to be handcuffed.

The guards left twenty-six men, naked and handcuffed, many of them hog-tied, with their wrists cuffed to their ankles, on the San Quentin green for several hours. A photograph taken from a helicopter overhead showed the naked and prone men; the first public knowledge of the day’s events at San Quentin would be visually associated with prisoners prostrate and humiliated. At one point, prisoner Allan Mancino claimed that his handcuffs were too tight, and a guard shot him in the buttocks. Lying near Mancino, Johnson dug his face into the grass and prepared to die.7

The guards uncuffed the prisoners only long enough to make them crawl on their elbows back to the building. That evening, they questioned the men, still naked and cuffed, about the events of the day. Then the guards beat them again and placed most of them in B section, the toughest unit within general population, now temporarily converted into an isolation unit. The rest were moved to the second floor of the Adjustment Center.8

San Quentin guards had physically overpowered the men that afternoon and spent the evening taunting them, reminding them of their powerlessness. They called all the prisoners “niggers” and turned the classic antiracist Civil War song about iconic abolitionist John Brown into racist ridicule: “George Jackson’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave,” they sang. “George Jackson’s body is rotting in the grave / The revolutionary soldiers are rotting in their cells.”9

In the weeks and months that followed, prisoners across the country went on hunger strikes or engaged in other forms of nonviolent protest to mark his death. The most famous reaction occurred at Attica, a medieval-looking prison in western New York, where a silent memorial for Jackson demonstrated prisoner unity and led to a massive four-day rebellion in mid-September. On the outside, a variety of radicals taken with Jackson’s message of retaliatory violence attacked institutions of state authority, bombing Department of Corrections offices and shooting at police officers to protest the loss of an articulate symbol of revolutionary hope. The Weather Underground blew up the offices of the California Department of Corrections, and a unit of the Black Liberation Army killed a police officer in San Francisco.10 Others marked the occasion more solemnly. The two years following Jackson’s death saw the creation of the George Jackson Health Clinic in Oakland, run by the Black Panthers, and the George Jackson Prisoner Contact Program in Scandinavia. The Black Panther Party’s survey for potential recruits after 1971 included questions about Jackson and other black political prisoners.11 Countless memorials, sung and spoken and visualized, paid tribute to Jackson for having inspired the better selves of oppressed people, especially men. Jackson himself participated in a certain memorialization through his book, Blood in My Eye, which was published in early 1972.

The response to Jackson’s death provides a useful staging ground for examining the larger field of political action made possible through the limitations imposed by the prison. Premised on repression, the prison does not eliminate politics but rather seeks to control its emergence and shape its form. Jackson’s death offered an extreme lesson in the social dynamics inherent to the prison. In death as in life, the figure of George Jackson—or, more precisely, the ways in which some groups laid claim to the figure of George Jackson—was enmeshed in bigger struggles over the form and function, the race and gender, of power in the United States.

George Jackson lies dead in the San Quentin courtyard on August 21, 1971. Jackson was shot by guards as he ran out of the Adjustment Center after leading prisoners in a brief takeover of the unit. Courtesy of the People of California v. Bingham et al. trial records.

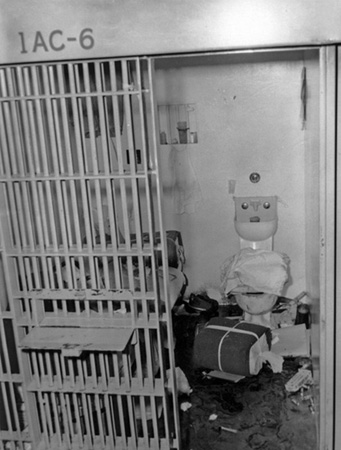

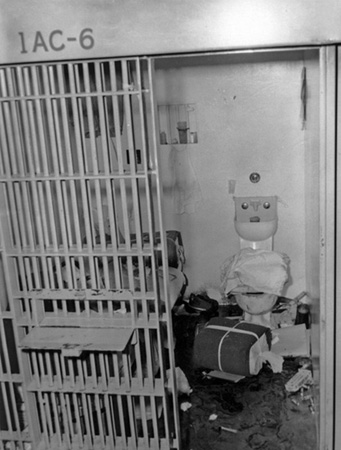

San Quentin Adjustment Center cell 1AC-6 on August 21, 1971. This is the cell where George Jackson spent most of the last year of his life. Several guards were brought to the cell and had their throats slit after Jackson temporarily took control of the unit. Courtesy of the People of California v. Bingham et al. trial records.

In their confrontations with confinement, opponents of the prison learned a political style that sought to make death into a generative force. For systems where death is an overdetermined outcome, death is not just the ending of life. It is the condition of life.12 In the prison, as on the plantation, the battlefield, and other sites so structured by the loss of life, death defines the meaning of being alive. The immediate fear or threat of death characterizes the communities that people form in these circumstances. Prison, as scholar Dylan Rodríguez argues, is the closest approximation to death a living person is likely to experience.13

Prison organizers on both sides of the wall formed social bonds through confrontations with death. Three forms of death animated prison organizing: social, spatial, and physical. Socially, the law exempted prisoners from moral value; their criminal record suggested that they deserved punishment, and they became objects rather than subjects of the law. The prison adds the invisibility and isolation of spatial distance to the open-ended exclusion of being denied access to society’s institutions and rights. Finally, as Jackson’s killing makes clear, the physical death of dissident prisoners exemplified the absent presence at the heart of prison radicalism.14

With death comes memory. Because of the prison’s geographic remove, maintained through extreme force and a prevailing ideology that disregards criminalized populations, prisoners are forcibly exiled to areas that geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls “forgotten places.”15 To organize in and against the prison, then, is an act of memory. It requires remembering, across the divide of space more than time, the existence, the humanity, of those in prison.

The memorial work at the heart of prison radicalism generally takes many forms, from attacks on the prison system to a variety of efforts geared at prisoner empowerment. At the center of each of these efforts is a struggle over knowledge: the particular ways of knowing generated by secretive and punishing institutions. Rigid, confining, and aggressive, the prison invites the pursuit of knowledge as one way to escape the strictures of isolation, to maintain connections to a life outside. By its structure, the prison lends itself to oppositional forms of organizing that revolve around producing and sharing knowledge. Prisoner study groups and memoirs, investigations into prison conditions, communication between prisoners and those outside of prison—all engage the access and transmission of knowledge. Even attacks on the prison system or other symbolic representatives of the criminal justice apparatus constituted knowledge struggles because insurgents in the 1970s hoped that such violence would provide teachable moments revealing the “true” nature of the system.

Although it may be a school of a sort, the prison has a pedagogy different from those found in other sites of education. Jackson’s death and the responses it generated reveal the ways that prison always structured political expression. The pedagogy of the prison is a multifaceted struggle over knowledge, identity, and statecraft. These facets manifest in the interplay between the structure of the prison and the agency of the prisoners. In foreclosing many traditional means of political expression, the prison created new opportunities for mobilization that prisoners and their supporters worked to seize. Indeed, the pursuit of knowledge and transparency was a centerpiece of prison organizing. These activists worked to make the prison knowable to those outside its walls. The acquisition of knowledge was critical to their efforts. From basic literacy to theories of revolutionary change to the origins of humanity, prison organizing was characterized by prisoner efforts to learn and study. Because Jackson’s erudition was so central to his appeal, many prisoners accelerated their study after his death.

The response to Jackson’s killing illustrated what anthropologist John L. Jackson Jr. has described as the “racial paranoia” that emerged after civil rights legislative victories. It is characterized by “extremist thinking, general social distrust, the nonfalsifiable embrace of intuition, and an unflinching commitment to contradictory thinking.”16 The unanswered questions of Jackson’s death—How did he get a gun? What role did authorities play? Who knew what and when?—sparked a larger battle over what knowledge the prison either made possible or foreclosed. The lack of a clear, agreed-on story of how he died made George Jackson an even more potent figure: the symbol leftists needed to believe that the prison was not a totalizing force and that law and order advocates needed to justify an expansion of precisely the system that had created him. As different factions battled over Jackson’s memory and legacy, they engaged troublesome claims to political authenticity that were steeped in the prison’s gendered conservatism. His spirit continued to haunt the prison, greeting newly politicized prisoners and terrifying their ostensible captors. The haunting presence of death, the problematic allure of authenticity, and the enduring power of education as a response to confinement all constituted the prison’s pedagogy.

“A BAD EXAMPLE FOR THE OTHER SLAVES”

The mourners filed into St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church in Oakland to a recording of Nina Simone’s “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free.” Simone’s soulful and aspirational melody captured the spirit of Jackson’s work. When she sang, “I wish you knew what it was like to be me / then you would see that every man should be free,” she gave voice to what supporters most appreciated about Jackson—his ability to speak of universal freedom from the particular place of prison. The song suggested that the United States understood neither the subjection nor the aspirations of the black condition. As the first eulogy of the day, the song suggested that black prisoners represented the dialectic between hope and despair, oppression and liberation.

Although fewer people attended this funeral than the one for Jonathan Jackson, the church was filled beyond capacity. Many of the two thousand people present could not squeeze inside; they listened to the proceedings over loudspeakers. Father Earl Neil, who worked closely with the Black Panther Party, presided over the funeral. In his eulogy, Neil described Jackson as a martyr in the biblical sense. “To us, George was a fire that never went out,” Neil said, after thanking Georgia Jackson for giving the world her two sons as an offering “to the liberation of our people.” The Jackson brothers, Neil said, were the latest heroic figures to contest black confinement. “The black condition is our imprisonment,” he said, arguing that this condition made black unity essential in the face of white supremacy. “George has brought us together today. . . . We have been brought together by his spirit, by his passion,” across differences of race, age, and gender. “But we are going to stay together when we leave here,” Neil cautioned. That unity in action marked Jackson’s presence. “George is with us today. He is telling us to rise up, to take steps toward freedom, to not lay around begging for freedom.”17

In his remarks, Panther leader Huey P. Newton described Jackson as part victim, part Superman. Newton found Jackson’s superheroism both in his military approach to the prison and in his far-reaching analysis of confinement as a problem of the racial state itself. Newton used this second point to argue against the government’s claim that Jackson was trying to escape, saying that his assessment of American society was too sophisticated for him to attempt an escape from the Adjustment Center. He was too good a writer to be so bravura an actor. According to Newton, Jackson realized that “you don’t break out of prison into freedom. It’s just an extended wall. . . . George realized the wall was very large. He realized that those prison victims were inside the wall and outside the wall, and this is why he began to write.”18 Jackson’s connection to the victims inside the wall was reflected in the choice of honorary pallbearers: John Clutchette, Fleeta Drumgo, Jonathan Jackson, Ruchell Magee, Hugo Pinell, and “all revolutionary brothers in the prison camps across America.”19

After the Bay Area funeral, Jackson’s body was flown to Mt. Vernon, in southern Illinois, to be buried in the family plot next to his brother. Several members of the United Front, a Black Power group in Cairo, Illinois, attended the funeral, alongside the Jackson family and close friends. Uninvited, the FBI and area police also attended the burial, as they did the Oakland funeral service. In addition to their long-standing interests in monitoring black radicalism, officials wanted to see whether Jackson’s death would spark violent retaliations. Distrustful of the media as well as the government, Georgia Jackson barred the news media from photographing her son’s burial. A few mourners punched two photographers and tried to destroy their film after they took pictures against the family’s wishes.20

Pallbearers load George Jackson’s casket, draped in a Black Panther flag, into the funeral car as thousands of attendees raise clenched fists, August 28, 1971. Georgia Jackson, who had lost both of her sons in a twelve-month period, is in the background (partially obscured), wearing sunglasses and with her fist raised. Photo © 2014 Stephen Shames /Polaris Images.

As they mourned, Jackson’s supporters raised questions about the circumstances of his death. The immediate response seemed quite in line with Jackson’s desire that his death would serve pedagogic ends. Jackson was fond of Che Guevara’s exhortation of a revolutionary death: “Whenever death may surprise us, it will be welcome, provided that this, our battle cry, reaches some receptive ear, that another hand reach out to take up weapons and that other men come forward to intone our funeral dirge with the staccato of machine guns and new cries of battle and victory.”21 In and out of prison, followers of Jackson and Guevara tried to heed their call. Bay Area activists demonstrated at the prison gates, while supporters abroad protested outside U.S. embassies.22 His mother called for a UN investigation, and others continued to call for independent tribunals to investigate his death. (As late as 1975, some Bay Area activists continued to call for such an investigation.)23

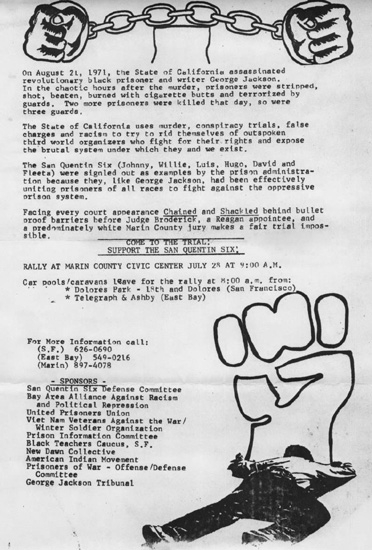

A flyer distributed by Bay Area activists encouraging people to attend the trial of the San Quentin 6, ca. 1975; the image of Jackson’s prone body flowing into the clenched fist was used throughout the mid-1970s. Among the distributors of this leaflet was the George Jackson Tribunal, which was an effort to establish an independent investigation into Jackson’s death. Courtesy of It’s about Time Black Panther Archive.

Inside the AC, prisoners tried to circumvent their now incommunicado status. They wrote an affidavit detailing the beatings they received and the constant threats they faced. Ruchell Magee wrote most of it, and prisoners circulated hand-copied drafts to one another for comment. All twenty-six men remaining in the AC signed onto it. Drumgo smuggled it out of the prison and into a court hearing the week after Jackson’s death. The collective statement was a small sign of multiracial political unity among the prisoners against what officials, relying on the standard canard of carceral divisions, were already describing as a race war.24 The family members of those incarcerated at the Adjustment Center and other activists pressed for public access to investigate claims of prisoner abuse. San Quentin authorities permitted two delegations to tour the prison: one group of three conservative journalists and another group of four liberal black politicians and professionals. Both delegations found evidence of abuse and isolation but disputed the prisoners’ claims of torture.25

The most dramatic responses, however, came from male prisoners around the country. To them, Jackson had exposed a vulnerability of the prison system. In death even more than in life, he was the figure they needed to believe in a power greater than the system that caged them. His influence was clearly visible at Attica, in Upstate New York, where prisoners responded to the news of Jackson’s death by launching a silent protest and fast. For several months, they had been pressing administrators for a variety of improvements to their living conditions, but the one-day silent hunger strike demonstrated a dramatic unity among prisoners that buoyed their spirits and terrified the guards.26

Two and half weeks later, on September 9, a scuffle between a small group of prisoners and guards spilled over into a full-blown rebellion as prisoners seized control of Attica’s D yard. For the next four days, prisoners created a minicommune while surrounded by police and observed by national media. Their negotiating power rested on the guards they had taken as hostage, but the revolt’s political aims were evident in the passionate declarations emerging from the prison. “We are men, not beasts, and we will not be treated or beaten as such,” they declared in a collective statement that accompanied a set of demands. The men selected a negotiating committee that included representatives of the Black Panther Party, the Nation of Islam, and the Young Lords as well as attorney William Kunstler, journalist Tom Wicker, and politician Herman Badillo. The rebellion seemed a living testament to Jackson’s political project of prisoner unity against the prison system, since the uprising seemed to provide the conditions under which the prison’s notorious racial divides faded in light of united prisoner action. “The racial harmony that prevailed among the prisoners—it was absolutely astonishing, that prison yard was the first place I have ever seen where there was no racism,” Wicker recalled.27

New York governor Nelson Rockefeller refused to meet with the rebels, however, and on September 13, he ordered state troopers—some of them armed with their personal rifles—to retake the prison. The troopers gassed the prisoners from a helicopter and then opened fire, killing twenty-nine prisoners and ten of the hostages.28 State troopers forced the survivors to strip naked and crawl through mud as state photographers captured their humiliation from helicopters above. Guards beat the naked captives with clubs, burned them with cigarettes, and hurled racial epithets at them along with threats of castration, torture, and murder.29

The violent retaking of Attica replayed the events at the San Quentin Adjustment Center three weeks earlier but on a grander scale. Indeed, the two incidents became joined in the radical imagination for years to come. In both cases, the state response targeted the symbolic as well as the physical power prisoners had demonstrated. Attica was even more spectacular than San Quentin, unfolding over several days in a heavily televised (though still largely circumscribed—the government barred news media from flying overhead during the retaking of the prison) manner involving thousands of prisoners and an utterly avoidable tragic ending. Prisoners had forced authorities to carry out their brutality in public, and though the incident failed to incite popular rebellion, it did cement Attica in the public consciousness and cultural imagination. The Attica rebellion was a fixture of the 1970s: the prisoners faced trials for their dissent, a special committee investigated the rebellion and the state response, and Rockefeller faced questions about his military response when he ascended to the vice presidency in 1974. “Attica” became a rallying cry, an example of state violence and a plea for justice. It was rendered most powerfully so in the 1975 film Dog Day Afternoon, based on a 1972 incident, when a bank robber (played by Al Pacino) leads the crowd gathered around the bank in chanting “Attica, Attica” in a rebuke of police authority.

The state’s response at Attica demonstrated that while arguments for political spectacle might have come from the Left, their execution was always more potent and dramatic when carried out by the state. Initial news reports falsely claimed that the dead hostages had been killed by prisoners. Further, officials initially made the specious claim that some of the hostages had been castrated, suggesting that such emasculation necessitated the state’s overwhelming show of force in response. For all the public concern over prisoner actions, the state proved far more determined to use swift, brutal violence and to do so in ways calculated to torment the spirit of resistance as well as the bodies of resisters.30

To destroy the Attica rebellion and erase the memory of George Jackson required an ideological assault on the popular idea that prisoners could be intellectuals. In keeping with that spirit, writers from Time described a “crude but touching” poem that Attica prisoners had scrawled onto the wall during the rebellion. However, the journalists did not realize that the poem was Claude McKay’s classic ode to black resistance, “If We Must Die.”31 Written in 1919, during an earlier generation of racial terrorism, McKay’s poem insisted on the honor of a dignified death amid a militarily superior force.

The poem was a fitting epitaph for the Attica uprising.

Denying the intellectual capacities of people in prison only strengthened their resolve to see Jackson as a hero, proof that the black male prisoner could fulfill a revolutionary purpose. Part of Jackson’s appeal lay in his pedagogy of black masculinity as an insurgent force. For other men in prison, Jackson’s blackness was defined through his masculinity. An Illinois prisoner described Jackson as “everything and some of what all twenty-some-odd million Blacks in this strange land of North America should be: A Real Bad Nigger.” In keeping with the various descriptions of Jackson’s physical capabilities, this prisoner described the other killings of August 21 as proof of Jackson’s heroic victory: Jackson, he said, killed five people before they killed him. Oppositional to the end, Jackson was the ideal prisoner. “Therefore, we—in these prisons—must spend long hours studying, to live up to that image.”33 Echoing Ossie Davis’s famous eulogy of Malcolm X as a “shining black prince,” a San Quentin prisoner called Jackson “the epitome of manhood.” To him, Jackson’s manhood was measured by his pedagogical impact: he had taught prisoners political and physical literacy.34

Several prisoners in the San Quentin Adjustment Center released a statement proclaiming that they would “vindicate” Jackson “because we are the ones who knew him best and loved him the most.” The statement, like the AC prisoners’ affidavit, described the severe physical reprisals the men had experienced.35 In her memoir, Angela Davis called Jackson “a symbol of the will of all of us behind bars, and of that strength which oppressed people always seem to be able to pull together.”36 Gregory Armstrong, the editor of Soledad Brother and Blood in My Eye, wrote that Jackson had been killed near the prison walls because he was attempting to draw guard fire away from the other prisoners housed in the Adjustment Center: “He sacrificed his own life to save them from an official massacre. This would only have been in keeping with the character of his entire life.”37 Like other martyrs, then, Jackson was said to have chosen his death in order to give others life.38

Jackson gave voice to a broader political impulse that characterized radical movements of the early 1970s, whereby the existence of political prisoners signified a reason to pick up arms. Political prisoners became symbols of struggle in Germany, Ireland, Palestine, South Africa, and elsewhere. Their images adorned street murals, their statements were read at rallies, their freedom was demanded through a variety of demonstrations, their continued incarceration was used as justification for a series of plane hijackings, shootings and bombings. George Jackson was the American representative in a global iconography of prison dissidents that included figures Ulrike Meinhof, Bobby Sands, Leila Khaled, Nelson Mandela, and numerous others.39 In each case, the prisoner served as a call to arms, a figure whose disappearance by the state convinced others to adopt a voluntary disappearance into the ranks of guerrilla war. Political prisoners signaled a paradox of state power, showing at once a top-down cruelty to the individual and a bottom-up inspiration in the collective of which they were a part. Internationally, however, political prisoners tended to be figures imprisoned for their actions as part of political movements. Because Jackson joined radical movements only after being incarcerated, his inclusion in the pantheon of political prisoners opened the door to a wider critique, a larger rejection of the prison system itself.

Beginning shortly after his death and continuing throughout the 1970s, Jackson’s image gave rise to a variety of spectacular assaults on police authority. This approach came straight from Jackson’s political playbook. In marking Jackson’s death with two bomb attacks against buildings housing offices of the California prison system, detonated hours before Jackson’s funeral, the Weather Underground commemorated Jackson “for what he had become [at the time of his death]: Soledad Brother, soldier of his people, rising up through torment and torture, tyranny and injustice, unwilling to bow or bend to his oppressors.”40 The “George L. Jackson Assault Squad” of the Black Liberation Army, a splinter group of the Black Panther Party, announced that it had killed a San Francisco police officer in revenge for the “intolerable political assassination of Comrade George Jackson in particular, and the inhumane torture of P.O.W. (Prisoner of War) Camps in general.”41 In the Pacific Northwest, a clandestine group calling itself the George Jackson Brigade carried out a series of bombings and attempted prisoner escapes in the late 1970s. Its first action was to bomb Washington’s State Department of Corrections to draw attention to abuse of prisoners in the Walla Walla prison. Because Jackson had promised to torment his oppressors from beyond the grave, his name seemed a fitting title for this small group’s actions—a way to remind the rulers that Jackson would forever haunt them. In 1972, an unrelated group of San Quentin prisoners also called itself the George Jackson Brigade.42

Revolutionaries around the country used Jackson’s name as inspiration to mark their antagonism to the prison system. In the Northeast and in the Bay Area, separate groups used Jonathan Jackson’s name (and that of slain Attica prisoner Sam Melville) when carrying out other bombings of government buildings.43 In the Bay Area, the “August 7 Guerrilla Movement” claimed responsibility for several attacks, including a 1973 shooting of a police helicopter that killed two officers and a communiqué threatening to kidnap the director of prisons unless certain prisoners were released (a threat never actualized).44 The Bay Area prison movement continued to produce other attempts at armed struggle, among them the New World Liberation Front, the Symbionese Liberation Army, and Venceremos. And to the extent that these efforts produced more prisoners, they added experienced organizers to the prison population as well as inadvertently providing public support for harsher sanctions as part of the domestic war on crime that undermined revolutionary groups.45

The climate of anger and revenge surrounding Jackson’s death was worsened by the state’s failure to adequately explain the circumstances. While crucial elements of the state’s version of events were discredited, no suitable alternative theory supplanted it. The full extent of infiltrators and agents provocateurs among the Black Panther Party and other organizations connected to the prison movement remains a mystery decades later.46

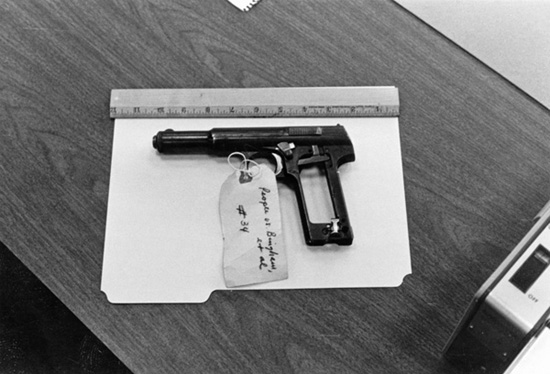

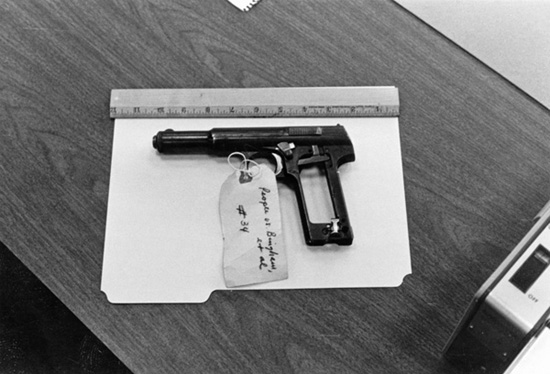

Officials could not even reach a consensus on basic details such as what kind of gun Jackson had. In the week following Jackson’s death, prison officials posited six different guns of varying sizes before ultimately settling on an Astra 9mm. But such a heavy pistol would not have fit in Anderson’s tape recorder (the way officials said the gun had entered the prison) or under the wig where Jackson supposedly hid it. The last known sighting of the particular Astra that Jackson allegedly used occurred when police arrested its owner, Black Panther Louis Randy Williams: How did a gun in state custody make its way to San Quentin prison?47 Officials failed to explore alternative theories for how Jackson got the gun and neglected to interview several potential suspects, including Anderson and other people in the visiting room that day.

The official story of Jackson’s death did not make sense, and the confusion seemed only to confirm what Jackson had been saying about the prison as a site of black death premised on open warfare between guards and prisoners. James Baldwin poignantly described Jackson’s death as an extension of his imprisonment, itself an extension of a longer black imprisonment. Writing in the Black Panther newspaper, Baldwin said that “George remained in prison because something in him refused to accept his condition of slavery. This made him a bad example for the other slaves, because the Americans still believe that they are running a plantation, and that this plantation is now the world. In the eyes of America all of us are Black today, and if you think I am exaggerating take a look at the results. . . . [F]rom this point on, every corpse will be put on the bill that this civilization can never hope to pay.”48 The prison, with its constant reminders of extreme state control, generated a distinctly racial paranoia that Jackson’s death epitomized. Baldwin summarized this feeling succinctly when he said that “no black person will ever believe George Jackson died the way they say he did.”49

Jackson was the latest in a string of slain black male revolutionaries who had defined the 1960s era—Medgar Evers and Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr. and Fred Hampton, as well as the larger number of men and women killed by police or vigilantes. To many observers, Jackson’s demise in an enclosed prison yard made his killing even more emotional. Whether it was the physical death of black men through murder or their social death through confinement, activists were increasingly using the word “genocide” to explain American racism.50

Four members of the East Palo Alto municipal council passed a resolution calling for an investigation into Jackson’s death and declared their “disgust and dismay at this atrocious act of genocide.”51 Actor-activist Ossie Davis argued as much in his 1970 foreword to the reprint of We Charge Genocide, black communist William Patterson’s 1951 petition to the United Nations detailing American racism. In a passionate introduction dated ten days after Jonathan Jackson’s raid on the Marin County Civic Center, Davis argued that “genocide” was the only label adequate for the combination of expendable labor and brute force to which the United States subjected black people. “History has taught us prudence—we do not need to wait until the Dachaus and Belsens and the Buchenwalds are built to know that we are dying,” Davis wrote. “We live with death and it is ours; death not so obvious as Hitler’s ovens—not yet. But who can tell?”52

The fear of black genocide was not just a polemic. Several analysts in the early 1970s argued that black labor was being eviscerated by a combination of automation and white supremacy. With no more need for black labor, they argued, the U.S. elite no longer had any need for black people—hence their abuse by police and incarceration. Charting the economic health of black communities after World War II, sociologist Sidney Willhelm argued that “white racism and elimination from sustained employment bring the American Negro to the identical, ultimate fate of the American Indian”—that is, spatially confined and at risk of annihilation. Willhelm’s was a prescient analysis of black fates at the onset of what has been called the neoliberal era.53

Jackson’s death taught the world about American racism. His writings and the prison conditions that produced them facilitated the increasing significance of race in the emerging postcolonial world. Cultural theorist Manthia Diawara remembers Jackson and Davis, along with Eldridge Cleaver, Malcolm X, and Muhammad Ali, among others, introducing an American blackness into Mali, then recently independent of French colonialism. These figures of black American defiance, most of whom were or had previously been in prison, taught Africans a certain practice and ideology of blackness. Diawara and his high school classmates in Mali began to imitate “our black American heroes” in dress, nicknames, and linguistic style and “began to see racism where others before us would have seen [only] colonialism and class exploitation.”54 Knowledge of these figures, down to particular legal updates and other current events, became a cultural marker of independence. Through such knowledge, “African youth . . . were creating within us new structures of feeling, which enabled us to subvert the hegemony of Francité [French ways of speaking and thinking] after independence.”55

Jackson’s death confirmed to these black activists the genuine threat black prisoners represented to the U.S. status quo. In a eulogy written three months later, Guyanese scholar-activist Walter Rodney praised Jackson “because he discovered that blackness need not be a badge of servility but rather could be a banner for uncompromising revolutionary struggle.” Yet Jackson’s killing also exposed the depth of the American racial order: as Rodney wrote, “Ever since the days of slavery the U.S.A. is nothing but a vast prison as far as African descendants are concerned. Within this prison, black life is cheap.”56

One of the most enduring influences Jackson had was in France. Thanks to Jean Genet’s support, Jackson’s work circulated widely among the French intelligentsia, and his ideas informed the development of what ultimately became known as poststructuralist French critical theory. Historian Rebecca Hill argues that Soledad Brother “inspired the young Michel Foucault to think about the relationship of the reform of the soul to the maintenance of power.”57 Working with philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Gilles Deleuze, among other prominent intellectuals, Foucault was one of the spokespersons for the Groupe d’Information sur les Prisons (GIP), which investigated and reported on French prisons, borrowing from the American prison movement an approach that joined the public’s right to know with prisoners’ right to dignity. GIP released several reports about American prisons, including one about Jackson’s death.58

What most survives this encounter between black American prisoners and white French intellectuals is Foucault’s classic, Discipline and Punish. First published in 1975, the book makes no acknowledgment of Jackson’s influence, GIP, or the broader radical milieu in which Foucault traveled. Rather, the book offered a historical and theoretical examination of modern state power. Foucault argued that the prison colonized the souls of the condemned, with power relations encoded in the daily functioning of the institution rather than in sweeping spectacles of brute force. In particular, Foucault argued that the architecture of the classic prison worked through a “panopticon,” with prisoners becoming more docile because they might be under direct surveillance at all times by guards sitting in a central tower. His analysis was far more applicable to Europe than to the United States, where brute force remained a critical ingredient of race-making and state power, especially in the figure of the prison.59 Still, Foucault’s insights into the subtle applications of power through individual bodies have been taken up widely by scholars and others. While Foucault emphasized the eighteenth-century European prisoner as the normative carceral subject, his arguments about the constrictions of regulatory power could be found in Black Panther writings generally and Soledad Brother particularly.60

Jackson routinely described how the prison had dulled his emotional sensibility so that he remained affectively closed off as well as well as physically self-regulating. Jackson alternated between pride and lament in describing the ways imprisonment had forced emotional self-control on him. His frequent references to his rigid exercise regimen and the need to “repress the sex urge,” alongside the barely concealed sexual tension of his descriptions of his physical strength, show how the prison’s discipline worked its way through the body of the condemned. These elements of life in prison, the daily characteristics of living inside such extremely controlled and repressive institutions, formed the backbone of Foucault’s interest in the disciplinary elements of imprisonment as played out on both the individual prisoner and society at large.

These French critics reserved a special critique for the American media, so central to the circulation of Jackson’s image yet now so dependent on the state for its sources and credibility. Foucault and the GIP published a pamphlet, with an introduction by Genet, describing Jackson’s death as a “masked assassination.” They concluded that the prison was a state of war, a new front in revolutionary struggle, and that “the entire black avant-garde lives under the threat of prison.”61 The pamphlet indicted the media for colluding with the prison system in the “manipulation of public opinion” and the destruction of “the public image (so that Jackson would not survive) and the function (so that no one would take his place).”62 These missions were accomplished through descriptions of prisoner violence and guard beneficence as well as a campaign of deliberate misinformation about the source and caliber of Jackson’s gun. The GIP’s analysis of media coverage was neither incorrect nor complete. Because journalists lacked steady accounts of what happened inside San Quentin, the GIP argued that this confusion was part of tarnishing Jackson’s reputation; it obscured the truth but reveled in Jackson’s death as an armed killer.

Yet some journalists also did valuable research that exposed the contradictions in the state’s case. Reporters at the San Francisco Chronicle used a black model wearing an Afro wig to test the state’s theory that Jackson had hidden the gun under such a wig and walked, with the gun undetected, more than fifty yards accompanied by armed guards who did not notice the weapon. The Chronicle found that the gun did not fit under the wig and wobbled as the model walked just a few feet. In response, the government announced that the gun was of a different caliber, though in subsequent trials, officials again reversed themselves on the point. Likewise, a second autopsy, conducted a month after his death, revealed that Jackson had been killed by a shot in the back—not, as had been initially reported, in the head. Several prisoners in the Adjustment Center and other skeptics had alleged as much from the start, though some insisted that Jackson had also been shot point-blank in the head after being wounded.63

The gun that authorities alleged was smuggled to George Jackson. Officials claimed that Jackson received this nine-inch gun during a legal visit and that he hid it under a wig and walked seventy-five yards without the guards noticing the weapon. The San Francisco Chronicle tried to verify this story and found that the gun visibly wobbled with every step the model took. Courtesy of the People of California v. Bingham et al. trial records.

Journalists questioned some of the facts presented by government sources but did not, as many activists and artists did, reject outright the story of Jackson’s alleged escape. Instead, journalists attempted to re-create the details of the escape and fill in the missing pieces. In doing so, they were especially reliant on prison officials for access to the crime scene. They also recounted the gory details of the five other murders that occurred in San Quentin on August 21. According to the GIP, the blood-and-guts details of the events in the Adjustment Center served an ideological function, presenting the incident as a “savage massacre” committed by prisoners run amok.64Because journalists knew little of what happened inside the San Quentin Adjustment Center, they emphasized lurid details of violence—who had their throat slashed and in what order, how the victims spent their terrifying final moments, what words they uttered last. Even progressive journalists, lacking a viable counternarrative, were trapped by the constraints on access to information and resorted to the grim, knowable details. The mystery of George Jackson continued to haunt and confound, with the confusion enabling the prison to regain its symbolic authority.65

Dissident prisoners responded by challenging the media’s reliance on government sources. They identified the government and the media as twinned forces responsible for the prisoners’ confinement and most Americans’ negative views of the incarcerated. Prison officials, wrote Ruchell Magee, “will tell (not Pay) those foolish news media dogs to lie publicly. . . . [A] lot of people would hear where the pigs have charged people with a lot of verbal shit written on paper, and hear the news media lies and convict innocent people before they are tried.”66 Other prisoners accused the mainstream media of helping “fabricate a non-existent world” and of using “publicity tricks” to shape public consciousness against black demands. Against this enemy of a corporate media reliant on state power, some black prisoners encouraged self-reliance in pursuit of an anti-Establishment truth. They declared that all writers, amateur and professional, had a “sacred obligation” to make sure that “our people” know the “real things.”67

By critiquing the media for enforcing state violence, these prisoners maintained that the harshest elements of racism functioned through invisibility. The shroud of secrecy surrounding the prison pointed to the emerging racial landscape in which covert forms of racial categorization and the violence they enable have become increasingly central. As public policy formally embraced “color-blind” equality, the structures of racial inequality grew further entrenched. This seeming paradox, whereby the state has been “forced to exercise racial rule covertly,” gave credence to paranoid suspicions of official power and its machinations.68 In other words, the new racism would be characterized by what was unknown and unspoken, by what was hidden from view, where it had previously seemed to be defined by explicit references.

Black radical prisoners, then, worked to expose the new racial apartheid, in which physical isolation through heavily policed ghettoes and prisons would hide the extreme violence to which poor black and Latino communities were subjected. As a prisoner in Auburn, New York, wrote in a 1973 poem, “I am a political prisoner, charged with the unwritten / law of race.”69 Prisoners described blackness as the cause of both confinement and rebellion. In an interview with a journalist, Robert Blake, a black prisoner on the team negotiating an end to the 1970 uprising in the New York City jail system, described blackness in America as a form of natal alienation that prompted radical politics. “Q. What is your name? A. I am a revolutionary Q. What are you charged with? A. I was born black. Q. How long have you been in? A. I’ve had troubles since the day I was born.”70

If official racism now took cover in opaque institutions governed by administrative rather than explicitly racial segregation, its opponents needed to be vigilant regarding its origins. With an air of proselytization, prison activists cast their message as a signal flare against black genocide. As a result, they spoke with a great urgency. “A warning: BLACK PEOPLE: what is happening in San quentin maximum security concentration camp is only a small example of what is to come in the minimum security concentration camp” of society, declared a statement by an Oakland prisoner support group. “Your reactions will indicate how fast or slow they will go with their program of genocide. WE SEEM TO THRIVE ON DECEIT: AWARE BLACK PEOPLE LET THIS BE AWARNING [sic] ESPECIALLY TO YOU.”71 And because genocide is as much about the past as it is the future, prison activists appealed to a parallel sense of history. “Brothers and Sisters we care nothing about our Brother going down in White History,” wrote supporters of Ruchell Magee, “but we care very much that he goes down in Black History. You can only see to that. In the meantime, a lot of Black people’s hopes are pinned up in [Magee’s] moves.”72

“THEY’LL NEVER COUNT ME AMONG THE BROKEN MEN”

George Jackson was writing from the grave long before he was killed. In early 1972, his militant will and testament appeared publicly in the form of his second book, Blood in My Eye. The book’s dedication marked its militarist ambitions in an eerie testimonial to the author’s death: “To the black Communist youth / To their fathers / We will now criticize the unjust with the weapon.”

Jackson had completed the book in early August, less than two weeks before he was killed. The most important part, for Jackson, was that he completed the book without the same meddlesome interventions of attorneys and editors. It was not, like Soledad Brother, a heartfelt if selective description of his conditions or his political maturation. It was a manual for guerrilla war. “I’m not a writer but all of its [sic] me the way I want it, the way I see it,” Jackson said of the manuscript on August 11.73

Blood in My Eye emphasized revolutionary violence, especially from within the “principal reservoir” that “lies in wait inside the Black Colony” of ghettoes and prisons, against capitalism and the incipient fascist threat.74 A manual on the theoretical and practical underpinnings of guerrilla war, the book combined essays with theoretically driven (rather than emotionally expressive) letters. Unlike the largely chronological order of his first book, Blood in My Eye is arranged into thematic chapters to emphasize the political interventions Jackson wanted to advance. It is difficult to evaluate the extent to which Blood in My Eye reflects a change in Jackson’s thinking or whether the ideas he expressed were beliefs that editorial interventions had prevented him from expressing in his first book. Even with the goal of positioning Jackson as an innocent victim, Soledad Brother contained several passages about armed struggle and revolutionary violence, the central themes of his posthumous tome and a preoccupation in his conception of social change.

Blood in My Eye synthesized Jackson’s views on political violence and revolutionary symbolism. Jackson argued that revolutionary action could expose the criminal justice system by demonstrating the brutality of the American state. He saw prison radicalism as the natural conduit for the use of violence as a revolutionary strategy. “Only the prison movement has shown any promise of cutting across the ideological, racial and cultural barricades that have blocked the natural coalition of left-wing forces at all times in the past. . . . The issues involved and the dialectic which flows from an understanding of the clear objective existence of overt oppression could be the springboard for our entry into the tide of increasing world-wide socialist consciousness.”75

The book argued for symbolic politics of violence to destroy the prison’s prestige. In Jackson’s conception, such attacks would undermine popular support for the institutions of governance. He saw violence as a spectacular force to shift collective consciousness and break the “isolation” of repression.76 Even where this politics of violence invited greater state violence, Jackson held that “repression exposes” the state’s monopoly of force. He saw violence as a rupture in the hegemonic order: “Prestige must be destroyed. People must see the venerated institutions and the ‘omnipotent administrator’ actually under physical attack.”77 Institutions maintained their authority by popular acquiescence in their permanence; thus, they needed to be violently uprooted so that people could understand that institutions of control were not all-powerful. Jackson had learned that lesson by observing the toppling of colonial rule in the Third World as well as by seeing the prison movement emerge from a series of small skirmishes with guards and other officials. According to Jackson, the visible destruction of elite prestige, accomplished only through violence, was necessary to build a “revolutionary culture.” State violence in the form of police brutality was an effort to extend that prestige by using spectacular displays of force to coerce submission.78 Jackson hoped that revolutionaries could use that algorithm for their own ends.

Blood in My Eye was a manual for the urban guerrilla more than the imprisoned one, though both groupings revered the book. Jackson wanted to turn America’s black colonies, the carceral cities, into sites of revolutionary war. Jackson dramatically overestimated the potential for revolution that existed in 1971, but his description of the macabre metropolis proved prophetic. As the wars on crime and drugs expanded beginning in the 1970s, Jackson’s prophecy seemed to materialize. Everything but the black revolution came to pass, as one observer put it: the “armored personnel carriers, military helicopters, military style raids cordoning off entire sections of the ghetto . . . are a reality in urban America as a result of the War on Drugs and the militarization of law enforcement.”79 In short, Jackson’s critique proved far more salient and incisive than his proposed violent solutions.

Jackson had intended the volume to be a how-to book for the black urban guerrilla, but its ideas were indelibly shaped by the brutal mixture of constant racial violence and limited human contact that is the American prison. Not withstanding its singular emphasis on violence, Blood in My Eye can be read as a manifesto on the importance of symbolism. Jonathan Jackson was crucial to George’s attempt to theorize prestige as a locus of power. If Soledad Brother uses George Jackson’s letters to construct an image of a transformed prisoner, Blood in My Eye uses Jonathan Jackson’s letters to construct an image of a martyred revolutionary. Blood in My Eye describes Jonathan as a tragic example of this effort to destroy prestige as well as a theorist of this approach to violent exposure. The first part of the book consists of a running dialogue between the Jackson brothers in which the elder brother casts his fallen sibling as a hero. While George had been saying as much since Jonathan’s death, Blood in My Eye gave Jonathan more of a voice by reprinting some of his letters to George. Jonathan Jackson, like his brother, was imperiled for his actions, remembered through his words. George reprinted Jonathan’s letters as part of a dialogue so that people would know as well as wonder “what forces created him, terrible, vindictive, cold, calm man-child, courage in one hand, the machine gun in the other, scourge of the unrighteous.”80

Between Jonathan’s death and the publication of Blood in My Eye, however, Jonathan’s only written words that circulated publicly, as if to give insight into his motivations for attacking the Marin courthouse, were contained in an article published in his high school newspaper in which he acknowledged that he was “obsessed” with his brother’s case.81 Blood in My Eye revealed him to be less focused on George in isolation and more concerned with guerrilla war as a strategy of black revolution. In a November 1969 letter, for example, the younger Jackson argued that the ubiquity of police power was an illusion: “Their present show of strength is actually their weakness—show—they’re too visible.”82 Jonathan argued that the covert attacks of guerrilla war could demobilize elites and provide a potent source of power for the oppressed. George mythologized Jonathan as an alter ego: “He has to be the baddest and strongest of our kind: calm, sure, self-possessed, completely familiar with the fact that the only things that stand between black men and violent death are the fast break, quick draw, and snap shot.”83

The bleak urgency of Blood in My Eye revealed something about the conditions of its creation. As Jackson articulated the simmering state of war between prisoners and guards, he imbibed the symbolic uses of violence central to imprisonment. Violence is never just about hurting bodies; rather, it is about portraying an image of power, reinforced where possible by an architecture of domination. As the response to Jackson’s death and the Attica revolt made clear, Jackson’s emphasis on the symbolic dimensions of warfare proved a prescient analysis of how those in power utilized violence.

“HE WAS JUST TOO REAL”

Jackson’s attention to the subtleties of language and politics helped make Soledad Brother influential beyond the black literary canon. A student of the rigidly hierarchical disciplinary world of the prison, Jackson made profound observations of the ways institutions disenfranchise social as well as individual bodies. Such insights spoke to the zeitgeist of New Left critical theory and its offshoots around the world. Where authenticity was defined through alienation, the prisoner’s voice earned a measure of popular support.84

After reading an article about Jackson’s death in the fall of 1971, Bob Dylan, who had largely abandoned political songwriting by this time, immediately wrote a song, “George Jackson,” and recorded it the following day. Eight days later, the single hit stores. To ensure that radio stations would play the song, the record only featured two different versions of the song.85 A commercial flop that never made it to a full-length album, “George Jackson” was a musical elegy for slain authenticity, emphasizing Jackson’s impact and character: “Authorities, they hated him / Because he was just too real.” Through Jackson, Dylan performed the popular perspective that prisoners were too real, too truthful and potent, for American society to handle. Echoing black radicals, Dylan sang that America itself was a prison, with walls and barbed wire merely separating those in maximum security from those in minimum security. As Dylan put it, “Sometimes I think this whole world / Is one big prison yard / Some of us are prisoners / The rest of us are guards.”86

A number of analysts and partisans from a variety of perspectives used the trope of authenticity to debate Jackson’s significance. But authenticity emphasized the individual over the systemic, the hero or the villain over the collective. Even worse, the concern with authenticity naturalized a connection between black masculinity and confinement. The search for the “real” George Jackson, like the elaboration of prisoners as standard-bearers of revolutionary mettle, also trafficked in troublesome stereotypes about sexuality and aggression. People not only pursued the real George Jackson but interrogated those around him. His death provided an occasion to test his political worldview and his peers. Understood through authenticity, the pursuit of truth amid the prison’s secrets ceded victory to the conservative push for law and order. The metaphoric prisoner was easily incorporated into the revanchist imagination of punishment.

Throughout the 1970s, black music and cinema took the prison as their setting for exploring freedom and its opposites. James Brown’s 1971 live album, Revolution of the Mind, did not mention Jackson specifically but imagined imprisonment as an authentic feature of black life. The album cover featured a picture of Brown behind bars. “Revolution” was the most visible word in the title, and underneath it, Brown, with an Afro and a black leather jacket, resembled a Black Panther. The album title and imagery presented the prison as a natural site of black revolution. Also in 1971, B. B. King released a live album recorded in Chicago’s Cook County Jail, and the following year, jazz artist Archie Shepp commemorated the prisoner rebellion with Attica Blues. The bloody retaking of Attica alongside critiques of police brutality and American imperialism informed a series of pieces in which poet-musician Gil Scott-Heron connected the deaths at Attica to the wider cruelties of racial rule.87 Even at the end of the decade, Jackson remained a salient image of black resistance: the black British reggae band Steel Pulse called for “three cheers for Uncle George” in “Uncle George,” included on the 1979 album Tribute to the Martyrs.88

These tributes to black prisoners often displayed conservative gender politics. Songs about Jackson typically celebrated his masculine heroism. Only the a cappella group Sweet Honey in the Rock, founded by civil rights movement veteran Bernice Johnson Reagon, took seriously the political significance of black women prisoners, releasing a 1976 song, “Joanne Little,” that chronicled the story of a black woman prisoner in North Carolina who killed a guard who sexually assaulted her. “Joanne is you and Joanne is me / Our prison is the whole society,” they sang. More often, however, the cultural symbol of black women in relation to the prison system was often understood through heterosexual romance. Between Angela Davis’s arrest in 1970 and her 1972 trial, for instance, some of her supporters bought into the prosecution’s argument that Davis’s love for Jackson knew no bounds, when they claimed that the case was illegitimate because the two were really in love. Even some of Davis’s supporters, then, promoted a conservative view of black women’s activism. Whether victim or villain, these depictions of Davis as motivated by love minimized her political work. Davis did indeed express love for Jackson; such loyalty was not invented. But when described in romantic or sexual terms, this love depicted a hyperemotional irrationality more than political agency or legal innocence.

Two songs released in 1972 in support of Davis pursued this theme of criminal love. On their album Sometime in New York City, John Lennon and Yoko Ono open “Angela” with the suggestion that Davis was put in prison because “They shot down your man.” A picture of Davis, with an Afro and mouth wide open, appeared on the album cover, which was designed to look like the front page of a newspaper.89 The Rolling Stones also honored Davis with a stripped-down blues song, “Sweet Black Angel,” that is one of the group’s few explicitly political songs. In contrast to Lennon and Ono’s tribute, which critics regarded as banal and a softly sung protest anthem, “Sweet Black Angel” became an interesting artifact in the Stones’s repertoire. It is also a prime example of the patronizing ways in which white men have represented the sexuality of black women.90 Using an affected slave dialect, Mick Jagger sings about Davis as “a sweet black angel / woh / not a sweet black slave.” The song upholds her sexual symbolism, calling her a “pin up girl.” But with “her brothers . . . a fallin’,” now “de gal in chains.” The song ends with a call to “free de sweet black slave.”91 Such depictions neatly inverted the case against her: rather than challenging the idea that her legal predicament resulted from her unbridled passion, they gave this passion a positive sheen.

This passive, patriarchal view of Davis informed 1970s cinema as well. The low-budget blaxploitation genre produced a series of films that represented a cheap knockoff of Jackson’s image through a variety of violent, macho men and buxom women carrying out simplistic revenge fantasies against symbolic representatives of a white power structure. Davis often served as the caricatured and unacknowledged inspiration for the hypersexualized, Afro-wearing, weapon-wielding black woman fighting the (white) man, often to save her imperiled black male lover or avenge his martyrdom.92

Jackson’s death, Davis’s trial, and the violent end to the Attica rebellion became the vehicles through which people across the political spectrum tried to come to terms with life’s desperations. For some, the lesson involved the severity of incarceration combined with the shocking display of state violence. Prison activists and leftist attorneys described radical prisoners as bearers of civilization. Fay Stender, Jackson’s attorney and the architect of the Soledad Brothers defense campaign, felt that “person for person, prisoners are better human beings than you would find in any random group of people.” Reflecting on her work with men in California prisons, she said, “They are more loving. They have more concern for each other. They have more creative human potential.”93 William Kunstler, perhaps the preeminent leftist attorney of the era and a negotiator for the Attica Brothers, hyperbolically described prisoners as the basis for modern civilization. “If it was not for the difficult roads that these Brothers and Sisters chose, we would still be living in a jungle,” he said in a 1972 interview.94 Writing less than a month after Jackson was killed, Mel Watkins suggested that Jackson had the last word. His death put the spotlight on prison in ways that other challenges to black confinement had not. “The idea that all black Americans are symbolically imprisoned is, of course, a cliché,” Watkins wrote in the New York Times. “But it may be realistically said that prison is an exaggerated facsimile of society for those who suffer from racism, violence and bureaucratic insensitivity.”95

Black prison narratives helped popularize an idea that prison was both a metaphor for and the epitome of the hidden constraints in American society. Many radical feminists made similar arguments about the confining limits of patriarchy. Pat Halloran of the Free Our Sisters Collective defined the prison as a ubiquitous component of patriarchal power. “For women, to be outside the walls of a jail is in some sense an allusion [sic]. . . . We must work not only to break down the stone walls that enclose some of our sisters, but to break down the barriers of written and unwritten laws that would call us criminal if we refuse to be slaves.”96 Others, however, took a more philosophical approach. “We all live in a prison of some kind, don’t we,” author Thomas Gaddis asked in his introduction to a 1975 anthology of prison writings, poems, and songs.97

Yet most people ultimately seemed more interested in the metaphoric prisoner, stuck in a job or a frustrating home life, than the one locked in a cage. In fact, several conservatives leveraged the fear of abstract confinement to push for more prisons and tougher sanctions. Demonstrating a destroy-the-village-to-save-it mentality, several prominent commentators justified punitive policies on the premise that they were necessary to prevent a larger, metaphorical confinement of homeowners scared to leave their property or upstanding white citizens imprisoned by fear of street crime. Such themes could be found in the growing popularity of vigilante films of the era, including the Dirty Harry (five films between 1971 and 1988) and Death Wish (four films between 1974 and 1994) franchises, among others. But it also animated public policy debates. Paradoxically, the confounding circumstances of Jackson’s death created space for critics to raise questions about his life and the way supporters had allegedly misrepresented it. Equally invested in Jackson’s symbolism, these critics attached that symbolism to a negative view of the prisoner. They objected that Jackson’s fame relegated to the shadows the other five people killed on August 21, 1971. These subsequent narratives of George Jackson increasingly described black people, prisoners, and black prisoners as threats.

The national perception of the George Jackson story was evolving from victimhood to villainy. This shift in Jackson’s significance utilized some newly revealed information but depended as much on a shift in the salience of facts that had been well known: his physical strength, for example, was now said to signal not an ability to endure confinement but his capacity for violence. Such depictions of Jackson appeared in initial reports of his death and increased in severity throughout the 1970s.

Conservatives treated Jackson’s death as a strange validation of the prison system’s harshness and the reason why it needed to become even more punishing. To do so, they appealed to well-worn tropes of black men as hypersexualized, violent brutes. Such efforts worked to reconcile an image of Jackson with the counterinsurgent aims of a rightward refashioning of the United States. California governor Ronald Reagan penned a New York Times opinion piece that used Jackson’s death to call for greater law and order. In “We Will All Become Prisoners,” Reagan argued that support for Jackson illustrated that society risked being imprisoned by “the falsehood that violence, terror and contempt for the moral values of our society are acceptable methods of seeking the redress of grievances.”98 Other prominent conservatives sounded a similar note. William F. Buckley Jr. praised the Los Angeles Times for posthumously emphasizing Jackson’s prior run-ins with the law rather than his victimization. Whereas liberals and leftists described Jackson’s incarceration in terms of his indeterminate sentence, Buckley, following the Los Angeles Times, noted that Jackson had been denied parole ten times in eight years and had racked up forty-seven disciplinary violations in that time. Buckley quoted several people, interviewed for the original news story, who described Jackson as having a violent temperament before and during his incarceration.99

Even without using Jackson as a symbol of the need for greater law and order, journalistic investigations into Jackson made him visible as the hypersexualized by-product of white imagination—the black projection of white fantasy. In a lengthy 1972 Esquire article about the relationship between Davis and Jackson, Ron Rosenbaum talked with an anonymous supporter of Jackson about his significance. Rosenbaum opens the article by describing a “pale yellowish stain” on the front of a flirtatious letter that Jackson had sent the woman—a letter she quickly removed from view. The move encapsulates Rosenbaum’s argument that the woman does not want to expose for public scrutiny troublesome aspects of Jackson’s personality, including his sexual advances. She later expresses this protective urge by telling Rosenbaum not to write about the semen-stained letter or Jackson’s note calling the document his “‘physical evidence of love.’” Rosenbaum, however, was more concerned with detailing what the woman says is not important about Jackson (his sexual exploits and aggressively flirtatious letters) than what she claims as his importance (his emphasis on multiracial class struggle).100 Like Buckley and Reagan, Rosenbaum charged that radicals had falsely represented George Jackson.

Buckley, Reagan, and Rosenbaum were among the first responders in a larger right-wing shift that described Jackson and other men of his station as dangerous criminals. For several years beginning in the mid-1970s, a series of books about Jackson described the radical Left more generally as imprisoned by a paranoid and violent fantasy. These texts included memoirs by Jackson’s editor, Gregory Armstrong (The Dragon Has Come, 1974), and his friend, James Carr (Bad, 1975), as well as Jo Durden-Smith’s investigative account Who Killed George Jackson? (1975) and novelist Clark Howard’s true-crime story about August 21 (American Saturday, 1981). Also in 1981, former New Leftist David Horowitz marked his hard-right turn by criticizing the prison movement in a magazine article about Fay Stender.101

Like American politics more generally, these narratives grew more conservative with time, and the more conservative the narrative, the greater closure it provided to the George Jackson story. The brief, popular romance with the radical prisoner as representative of broader social conditions was coming to an end in mainstream American intellectual life.102 A far more conservative set of ideas would gained traction, viewing prisoners as part of an intellectually inferior, preternaturally violent substratum of society that deserved nothing but force from the American state. From this perspective, prisoners neither needed nor deserved rehabilitation; they needed to be entirely removed from society.

Such ideas have ebbed and flowed throughout American history, and they did not go unchallenged in the 1970s. Indeed, these years featured the most self-consciously radical versions of criminology the American academy had yet known. But the revanchist mind-set increasingly converged with a wide range of official interests. Here was the intellectual culture that produced an unprecedented boom in prison construction and a public policy approach rooted in the idea of an undeserving “underclass.”103

A PRISON EDUCATION

The focus on authenticity obscured the ongoing work inside prisons, where George Jackson’s influence continued to inspire some male prisoners to better themselves through education and expanded political horizons. The pedagogy of the prison was an ongoing enterprise in California and around the country. As an institution rooted in classificatory regulations, administered by force and physical separation, the prison taught certain lessons to those who encountered it—whether as prisoners, guards, family members, or community activists. Those seeking to undermine the prison, whether from within or from without, had perhaps the sharpest instruction in carceral power since they crafted their own education alongside and against the messages delivered through confinement.

The pedagogy of the prison was a highly gendered education, facilitated by the rigid sex segregation of confinement. The focus on heroes—the need for heroes to demonstrate that the prison was not all-powerful—drew attention to individual prisoners or collective prison riots in ways that overemphasized physical confrontation (primarily in men’s prisons). Such an emphasis overlooked a variety of work by and on behalf of prisoners in both men’s and women’s facilities. It also overlooked the collective spirit that characterizes all forms of prisoner resistance.

More than anything else, the social life of prison organizing required creativity. Like the plantation and the slave ship, the prison combined quotidian and spectacular forms of punishment. Attorney Larry Weiss described San Quentin in the 1970s as comprising “90 percent boredom and 10 percent explosive danger.”104 To survive that combination required a great deal of ingenuity, which is how David Johnson and Hugo Yogi Pinell, denied reading material, found themselves playing game after game of chess on chessboards they made with stubby golf pencils and scraps of paper taken from the sacks in which their lunches were delivered. The men shouted out their moves from their individual cells, separated by thick sheets of steel and slabs of concrete. Sometimes other prisoners played, too.105

The prison provided the necessity out of which a variety of inventions sprung. Prisoners turned gelatin, toilet paper, and pen caps into devices that could publish clandestine newspapers, circulate banned literature, or turn off televisions when guards refused to do so. Creativity motivated prisoners to seek a variety of means of engaging people on the outside about prison conditions, global politics, and popular culture. Without a life of the mind, however it could be expressed, the social death of confinement would prove far more totalizing, far more destructive. That was the legacy they took from George Jackson.

Care work, in the form of building and sustaining human relationships through a variety of affective ties, lies at the heart of prison organizing. In institutions premised on isolation, collectivity itself was a vital tool of resistance that prisoners employed to preserve their physical safety, increase their collective capacities, and expand their social and intellectual horizons. Even those who agitated for violent conflict counseled looking out for one’s comrades at every step. Such solidarity was an article of faith for them. This emphasis on collectivity and care revealed a fundamental paradox of the prison, where cooperative struggle emerged through conditions of spatial death.106

As with any organizing project, prisoner organizing is possible only through relationship building, a process made more difficult and in some cases more enticing by the distance and danger of confinement. Prison activism requires the active labor of people who are not incarcerated to attract broader recognition and support for those who lack the physical mobility necessary to publicly state their case. Key to initiating and maintaining these relationships are family members and loved ones of the incarcerated, social justice activists, and activist or sympathetic professionals whose work brings them into contact with prisoners. In the 1970s, professionals—primarily attorneys, but also nurses and journalists—played a central role. Such relationships between prisoners and outside supporters had a distinctively gendered hue. Women, especially mothers but also partners, children, and friends, did much of the work to support both male and female prisoners.107