Chapter Six: Prison Nation

The fate of the black prisoner has always been intrically [sic] tied up with the fate of the imprisoned black nation and vice versa. In each instance, “gaining our freedom” remains the primary concern.

—SUNDIATA ACOLI, “The Black Prisoner” (1979)

George Jackson’s death gave many people imprisoned in the early 1970s a new life. Jackson had been the most effective spokesperson for prisoner grievances, and his death meant that new voices of discontent would need to emerge. One person who took up this challenge was Robert Lee Duren, who had been in prison since 1968. Prior to his incarceration, he had not expressed any interest in politics. His story was an increasingly familiar one: reared in poverty, he came of age amid gangs and widespread violence and ultimately got involved in increasingly antisocial behavior. In 1969, he was convicted of killing five people in the course of robberies in Los Angeles and sentenced to death.1

On August 21, 1971, he was confined at San Quentin’s death row, two floors above the Adjustment Center. Like everyone else there, he knew of the famous prisoners who were confined below him: Bato Talamantez, Ruchell Magee, Fleeta Drumgo, John Clutchette, and of course George Jackson. After police had regained control of the Adjustment Center, they were in a fury about the dead and wounded guards. According to Duren, guards slammed the cell doors of the Adjustment Center so hard that the vibrations reached the third floor.

Three days later, Duren saw Fleeta Drumgo on the afternoon news removing his shirt in court to show the judge the cigarette burns he had received from vengeful guards over the previous seventy-two hours. A half hour later, Drumgo and Clutchette were back at San Quentin and the guards turned up the exhaust fans as loud as possible—possibly to hide Drumgo’s screams. “We could hear it anyway,” Duren recalls. Duren flushed the toilet to create a vacuum, enabling him to communicate with Talamantez in the Adjustment Center below him. “Are Fleeta and John back from court?” he asked. “Yes,” Talamantez replied. “Was that Fleeta they’re beating?” Duren shouted down the toilet. Again the response came in the affirmative. “I got off the line then,” Duren says, ceasing his questions so as to avoid drawing attention to their surreptitious communication.

After a sympathetic guard told them how to reach federal judge Alfonso Zirpoli, Duren joined with other prisoners to draft a letter of protest about the violence at San Quentin. They sent it on August 26 but received no response. Duren felt helpless, defeated. He cried because “there was nothing to do.” Then he looked at a collage in his cell: it showed Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., and another black radical, probably Malcolm X. And Duren had a vision. “Angela Davis on the left, Malcolm X on the right, and Martin Luther King Jr. in the middle. Reverend King pointed his finger at me and said, ‘Get up, nigga. Nigga, get up!’ I felt this powerful surge of strength well up in me. I got off the bunk, faced the direction I thought his office was located, and said, ‘Warden, you might be god of this prison, but I will never bow down to you.’” Then he wrote another letter to the judge, solidifying a life of oppositional writing. He had joined the prison movement.

With the death penalty temporarily abrogated in 1972, Duren was moved from death row to the main line. In the coming years, he came to know many of San Quentin’s radicals, including former Black Panthers Geronimo ji Jaga Pratt and Jalil Muntaqim. Duren was a member of the prison chapter of the Panthers until fallout from the party’s 1971–72 split made the Panther label largely irrelevant to those outside of Oakland. Tensions within the party looked different to those in prison. Many of the incarcerated Panthers were sympathetic to or members of the Black Liberation Army (BLA), the party’s military offshoot. They opposed Huey P. Newton’s growing authoritarianism, drug use, and consolidation of party resources into the Oakland chapter. They especially opposed Newton’s lavish apartment and the Panthers’ involvement in local electoral politics, which included running Bobby Seale and Elaine Brown as candidates for office. The Panthers turned BLA members shared with Jackson’s imprisoned contemporaries a revolutionary analysis but often differed about strategies and tactics, and several of Jackson’s associates and students, most of whom had found politics after entering prison, organized themselves under the mantle of the Black Guerrilla Family (BGF).

Duren followed the lead of the Panthers he knew. He began to communicate with organizers outside of prison, too. Some of his letters and articles were read on Berkeley’s KPFA radio by sympathetic left-wing journalists. Duren’s life changed thoroughly as a result of his newfound political passions. Around 1975, Robert Duren converted to Islam and renamed himself Kalima (“one with the word”) Aswad (“the word”). Islam was reemerging as both a political and spiritual path for black prisoners. The Nation of Islam had fallen out of favor among many black militants in the early 1960s as a result of its antipolitical stance and its split with Malcolm X, but it experienced a resurgence with the death of Elijah Muhammad in 1975 and the conversion of the organization to traditional Sunni practice by Muhammad’s son and successor, Warith Deen. In prison, the NOI remained more politically passive, but Sunni Islam was gaining ground among politically conscious black prisoners. Islam, like other spiritual or political cosmologies, provided prisoners with a connection to communities beyond confinement. As prisoners learned to read Arabic and to care about the Arab world, Islam also facilitated a growing consciousness much in the same way Third World Marxism did. Several prisoners worked to join the two philosophies.2

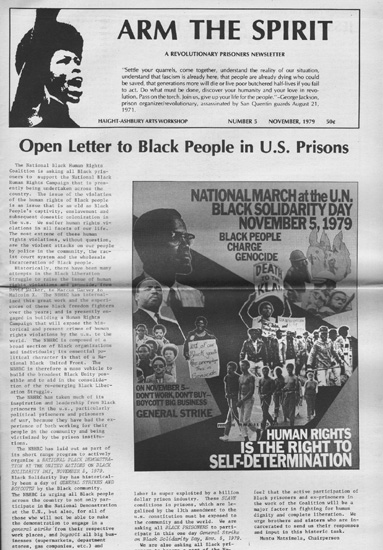

Aswad’s turn to Islam followed on the heels of the conversions of several other well-known black radicals, including Black Panther Anthony Bottom (now Jalil Muntaqim), former SNCC chair H. Rap Brown (now Jamil Al-Amin), and Revolutionary Action Movement cofounder Max Stanford (now Muhammad Ahmad).3 Aswad’s conversion signified his growing political involvement. His story shows the ongoing power of conversion, political and religious, for black prisoners during the end of the civil rights era in the mid- to late 1970s. As a writer, Aswad contributed to the ongoing preservation of prison-based print culture. He furtively distributed reports on prison conditions via handwritten notes. Then, with the help of black nationalists and white anti-imperialists in the Bay Area, Aswad and a small team of prisoners launched a newspaper, Arm the Spirit, that was one of several prison-based revolutionary nationalist publications that connected black prisoners to supporters and struggles on the outside. His role at the helm of one of the era’s most significant prisoner newspapers shows the innovative use of self-reliance strategies among dissident prisoners.

The prison had ceased to capture public attention as it had a few years earlier. Mainstream newspapers generally no longer had beat reporters for prison issues, and undercover journalists no longer got jobs in prisons to report on conditions inside. Those newspapers that had not lost interest in prison issues in the face of growing cries for law and order found that wardens increasingly blocked access to prisoners in hopes of avoiding publicity and eliminating opportunities for prisoners to communicate with the outside world. Journalist Jessica Mitford joined a lawsuit against Washington State’s McNeil Island prison after the warden there refused to allow her to interview prisoners involved in a February 1971 strike. The suit was settled in June 1973, when the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the prison’s right to deny journalists access. Having confirmed their power to control access, officials held an open house for journalists in early 1974.4 The message was clear: if prisoners were to remain connected to any outside public, they would need their own media.

The story of the radical prisoner print culture of the late 1970s is only just beginning to be told. The existence of this vibrant print culture challenges the received wisdom of the prison movement, which holds that prisons became politically barren by mid-decade.5 But prison radicalism did not disappear in a fit of self-destructive violence in the wake of George Jackson’s death or the bloody defeat of the Attica rebellion. It continued, smaller and more divided but persistent. The acquisition of literacy, self-education, and knowledge production remain a vital legacy of black prison organizing. In struggling to access and promote literacy, dissident prisoners affirmed that knowledge—as an active, living process of engagement—gives life meaning. Indeed, prisoner literacy in this context included both basic skills and political sophistication.6

Print culture was the backbone of prison organizing in the second half of the 1970s. These publications marked a new era in prison politics, enabling prisoners to continue functioning as political actors—to read the news, write their opinions, and debate political theory—after the high tide of prison organizing had ebbed. They provided prisoners with a means to define the issues on their terms. With less public backing and little in the way of a mass movement to support them, prisoners used media to sustain connections with other prisoners and with sympathetic outsiders. As collective action became more difficult, writing and editing provided an opportunity for politically conscious prisoners to continue working collaboratively with others on both sides of the prison walls. While publications provided the most consistent outlet for these alliances, they also manifested in several prisoner-initiated petitions to the United Nations.

This turn to media production coincided with dissident prisoners’ increased emphasis on revolutionary nationalism. With growing isolation inside prison and growing conservatism outside, revolutionary nationalism was one vital lifeline for intractable militants. Through appeals to unite the “black nation,” prisoners, especially black men, proposed large-scale solutions that positioned themselves as the best spokespeople for black people generally. Through newspapers and other writings, prisoners hoped to demonstrate the existence of a captive nation, consolidate political opinion among their rank, bolster a flagging black protest movement, and solidify alliances with a wide array of groups and communities. In short, dissident prisoners used print culture in the same way that nationalist movements historically have.7

Nationalism provided the framework for prisoners to connect with one another, to forge alliances outside of prison, and to identify with popular struggles across the world. A subset of a larger prison movement, black prison nationalism was part and parcel of the Third World liberation struggles of the 1970s. In Ireland and South Africa, Palestine and Puerto Rico, the battle lines of anticolonialism were more sharply drawn in the 1970s. Both colonial powers and their antagonists grew more determined, resulting in increased violent conflict on all sides. The prisoner remained a global symbol of national struggle under these conditions, an icon of the desire for freedom from oppressive external rule.

Within the United States, the consolidation of black prison nationalism, largely in men’s prisons, coincided with a rising tide of interest in prisoners among other social justice movements. Like earlier social movements, these movements worked to free those it considered political prisoners—whether defined as people incarcerated for their activism or as a result of the oppression they faced. Indeed, while prisoners faded from general public sympathy, many social movements—including those among indigenous and Puerto Rican communities as well as multiracial gay and feminist movements—challenged imprisonment in some fashion. The feminist and gay liberation critique of the prison built upon the analysis developed by the largely heterosexual, largely male prisoner writings of people such as George Jackson: the prison was a metaphor for the state and interpersonal violence that marginalized groups experienced as well as the physical place where such violence reached its logical conclusion. Yet out of that framework, these movements offered a more synthetic—later called “intersectional”—challenge to the prison. That is, they described oppression on a multidimensional axis that included gender and sexuality as well as class and race. And because women, gays, and lesbians often found themselves facing state violence through a wider range of institutions that included mental health hospitals, these movements developed a critique of what they called the “prison/psychiatric state.”8

The prison was the precondition for antiracist feminist coalitions. Several prominent cases of the era—including women who defended themselves from physical abuse, such as Joan Little (North Carolina), Yvonne Wanrow (Washington), Inez Garcia (California), and Dessie Woods (Georgia)—joined lesser-known but still significant struggles over prison conditions stretching from the California Institution for Women in Chino to the federal penitentiary at Alderson, West Virginia, and beyond.9 At the prison in Walla Walla, Washington, a group of prisoners, most of them gay, banded together and armed themselves to stop prison rape, calling themselves Men against Sexism. One of the founders of the group was Ed Mead, an avowed communist and revolutionary who was imprisoned for taking part in the George Jackson Brigade. A small clandestine collective comprising several former prisoners, the George Jackson Brigade carried out a string of bombings, funded by bank robberies, in Seattle in the mid-1970s in support of unions, prisoners, and revolutionary movements around the world.10

Former San Quentin 6 defendants, left to right, Bato Talamantez, David Johnson, and Willie Sundiata Tate speak at a rally with Inez Garcia at the San Francisco Civic Center, November 1976. Garcia was charged with murder for killing one of two men who sexually assaulted her in 1974. She spent two years in prison before her conviction was overturned on appeal. Hers was one of several mid-1970s incidents that brought together a large coalition of activists challenging the prison as a site of racial and sexual oppression. From the Collection of the Freedom Archives.

Its influence on a larger field of prison organizing notwithstanding, black prison nationalism by the late 1970s no longer enjoyed primacy of place among many progressives. But it was not for lack of trying. Black prison nationalism synthesized long histories of black anti-imperialism, the dynamics of prison protest, and the currency of national liberation. Like other forms of anticolonialism, black prison nationalism was both a worldview and a code of behavior. It offered an explanation of imprisonment and a personal praxis for resisting it, each one rooted in an internationalist sensibility that saw the United Nations as a possible ally.

The typical nationalist theme of self-reliance gained added power in the repressive condition of imprisonment. Prison nationalism allowed its adherents to experience a measure of power and self-control in an environment structurally engineered to deny them both. This nationalism expressed itself primarily, though not exclusively, through the media. As the decade came to a close, nationalist prisoners in California initiated a holiday, Black August, that would allow them to build a collectivity emphasizing the prison as the breeding ground for white racism and black resistance. Together with the Black August holiday, newspapers such as Arm the Spirit, Midnight Special, and The Fuse defined the prison as the root of the black nation.

Black prison nationalism expressed itself through a mix of connectivity and self-reliance. This combination is not the paradox it might at first seem. Black communities survived segregation on the southern plantation and in the northern ghetto with a similar balance of autonomous self-help organizations (both religious and political) and networked associations. The prison thrives on segregation: it segregates prisoners from the outside world, and then segregates prisoners from one another based on assorted administrative protocols. Segregation is a mode of discipline that prison officials around the country used with increasing impunity to isolate prisoner organizing. Through media and ritual, prisoners sought to demonstrate their sovereignty in a place that sought to incapacitate them altogether.

Black prison nationalism developed alongside another nationalism focused on imprisonment—a conservative law-and-order nationalism that increasingly relied on prisons as the response to crime and other social problems. In markedly different ways, both forms of nationalism naturalized connections among blackness, imprisonment, and nation building. During the 1980s, these connections were legislated through the war on drugs and a massive spike in prison construction, the likes of which the world had never before seen. Yet before mass incarceration existed, before a variety of state concerns and economic interests converged on cages as their panacea, incarcerated black radicals located the prison as the premier institution of the American racial state. For them, the prison was the centerpiece of the nationalist imagination. It structured white nationalism and sustained black nationalism.

“FOUNDATIONS OF THE BLACK NATION”

The concept that black people were a colony domestic to the United States, “a nation within a nation,” was a well-worn idea of the 1960s Black Power movement. This idea held that the pervasive history and ongoing structure of racism had bonded black people into a nationality. Black organizations, intellectuals, and politicians who disagreed on much else shared an analysis of their “national oppression.” In 1962, poet Amiri Baraka proclaimed, “Black is a country.” Ten years later, the Black Political Convention, held in Gary, Indiana, with the blessing of the city’s first black mayor, declared that it was “Nation Time!” If white supremacy imprisoned black people, it was no surprise that some would see black prisoners—the most literal embodiment of this oppression—as spokespeople for the black nation.

The blossoming of a distinctly prison-based black nationalism owes a great deal to Republic of New Afrika (RNA). Formed in Detroit in 1968, the RNA had always looked south, seeing a black national homeland in five former slave states of the Deep South: Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. This position revived one held by the Communist Party in the 1930s and echoed by many of the small communist parties emerging in the 1970s, which held that the history of racial slavery and its afterlives had created a colonized people in the Cotton Belt South.11 Unlike some of the communists, the RNA held that white supremacy colonized all black people everywhere. To them, the five states were not a base of oppression but the territory of a solution. At a time when popular attention to black politics focused on the urban North, the RNA turned its attention back to the Black Belt South. New Afrikans upheld the South as a more strategically defensible and historically authentic location of black politics than the city.12

The RNA consolidated several prominent themes of black radicalism in the twentieth century: cultural pride, anti-imperialism, spirituality, self-defense, self-governance, and economic uplift. The group attached these issues to its pursuit of reparations and a territorial homeland in the U.S. South. Its founders, Milton and Richard Henry (who renamed themselves Gaidi and Imari Obadele), had deep roots in Detroit and were leading figures in the rise of a national Black Power movement.

One of the group’s principal advisers was Audley “Queen Mother” Moore, who had a long and storied career with the Black Left. Born in 1898, Moore joined Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association in New Orleans during the 1920s, and Garveyism influenced the rest of her life. Impressed with the Communist Party’s defense of the Scottsboro Boys, Moore joined the CP in Harlem in the 1930s. She was a prominent fixture at party meetings, tenant campaigns, and street-corner speeches until she resigned from the party in 1950. She was also a lifelong member of the National Council of Negro Women, an intractable advocate for reparations, and a longtime supporter of black prisoners. In 1955, Moore, whose grandmother had been a slave, founded the Committee for Reparations for Descendants of U.S. Slaves. She mentored Malcolm X and members of the New York Black Panther Party. In 1968, four months shy of her seventieth birthday, Moore was one of the signers of the Republic of New Afrika’s Declaration of Independence.13

Self-defense advocate Robert F. Williams was the group’s first president, albeit more in name than function. Williams became director of the Monroe, North Carolina, branch of the NAACP in 1956. A military veteran, he advocated armed self-defense against white terrorism and offered weapons training to his chapter members. As a result of his militancy, the national NAACP leadership suspended him in 1959, and local white officials ran him out of town two years later. Framed on the typically ludicrous charges that characterized Jim Crow legality, Williams first fled to Michigan and then left the country, taking up residence in Cuba, Vietnam, and then China and Tanzania. From exile, he remained involved in and worked to internationalize the black American freedom struggle through writings and radio. The RNA helped coordinate his return to the United States in 1969, and he resigned his post with the group shortly thereafter.14

New Afrikan politics appealed to a broad cross-section of the black liberation movement. In addition to Williams and Moore, RNA founders Milton and Richard Henry could count as friends or mentors Malcolm X, militant activist-intellectuals James and Grace Lee Boggs, black nationalist minister Albert Cleage, and Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of an independent Ghana, who had attended Lincoln University with Milton Henry. At its founding, RNA officials included Muhammad Ahmad and Herman Ferguson of the Revolutionary Action Movement; Maulana Karenga of US (before he was expelled in 1969 after members of US killed two Black Panthers at UCLA); Amiri Baraka, then of the Committee for a Unified NewArk; H. Rap Brown of SNCC; and Malcolm X’s widow, Betty Shabazz.

As an organization, the RNA joined the Black Arts cultural renaissance with the militancy of the Black Panther Party and a spiritual cosmology informed by different expressions of black Islam. Like the Black Arts movement, the RNA professed a connection with Africa yet remained firmly rooted in the United States.15 The RNA shared the linguistic practices of many Black Arts figures, inspired by Garveyism and Rastafarianism. All of these groupings emphasized collectivity by capitalizing “We” and lowercasing “i” and spelled “Afrika” with a “k,” in keeping with Swahili’s use of the letter for the hard-“c” sound in English.16 Like other black nationalists, New Afrikans often changed their names to demonstrate a reconnection to their African ancestry and a rejection of the “slave names” they had received at birth. New Afrikans described the United States as “Babylon,” characterizing black liberation as a biblical struggle. And like the Nation of Islam, the RNA’s “New Afrikan creed” maintained the “genius of black people,” regulated personal behavior such as dress and hygiene, and upheld the heteronormative family as the natural unit of political community. The RNA’s commitment to black liberation as at least partly a spiritual enterprise mirrored the Black Arts cultural pride with elements of NOI doctrine likely inherited from Malcolm X’s tenure with the organization.

“New Afrikans” centered slavery as the origin of a new nation; only land and reparations could compensate for the oppression that originated with slavery. The idea of New Afrika attracted far more adherents than did the group that initiated it. The self-proclaimed New Afrikan Independence Movement emphasized not just “freedom” but “independence.” From its founding, the RNA constituted itself as a government in exile, complete with elected officials and consulates throughout the United States. RNA officials met with representatives from several foreign governments, including those of China and Tanzania. Like the Black Panthers, New Afrikans demanded a UN-supervised plebiscite for black people to determine whether they desired U.S. control. Even more than the Panthers, New Afrikans hoped that the rhetoric of international law would demonstrate the existence of the black nation. New Afrikans framed their politics in the language (if not always the form) of international law. New Afrikan prisoners labeled prisons “detention centers,” “death camps,” and “koncentration kamps,” categories governed by United Nations protocols on genocide and the treatment of prisoners of war.17 At Illinois’s Stateville prison, New Afrikan prisoner Atiba Shanna opined that talking of “P.O.W.’s, and in particular of Afrikan P.O.W.’s [in the United States] is a way of building revolutionary nationalist consciousness, and of realizing the liberation of the nation.”18

New Afrikan politics was part of a resurgent Pan-Africanism among black Americans in the 1970s. By the middle of the decade, Amiri Baraka had launched the Maoist-influenced Congress of Afrikan People in New Jersey; Revolutionary Action Movement cofounder Muhammad Ahmad formed the Afrikan People’s Party in Philadelphia; Owusu Sadaukai, an adviser to North Carolina’s Malcolm X Liberation University, had helped organize African Liberation Day and the African Liberation Support Committee in solidarity with continental national liberation movements; and several former SNCC organizers built organizations such as the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party or gatherings such as the Sixth Pan-African Congress.19 New Afrikan politics existed within an orbit of political identifications that sought connection to Africa while acknowledging that the experience of slavery made impossible any simple notions of return or reclamation. Adherents therefore argued that the New Afrikan nation formed in the seventeenth century, with the first arrival of African slaves on the shores of what had not yet become the United States.20

More than that of any other black political entity at the time, the RNA’s growth was facilitated rather than destroyed by the prison. While the RNA was one of several black nationalist groups, it exerted the greatest political influence over black prisoners after the split in the Black Panthers and the death of George Jackson. RNA politics spread rapidly through American prisons, leading many black prisoners to proclaim themselves New Afrikans. Many Black Panthers in the 1970s, especially in California and New York, declared themselves New Afrikans when they were incarcerated. Other black prisoners, politicized by the conditions of their confinement, also turned to New Afrika.21

Indeed, the RNA’s framework proved popular with dissident black prisoners. Small groups of prisoners in several midwestern and southern states, sympathetic to New Afrikan politics, organized collectives called Black On Vanguards. The name was chosen to connote racial pride as the antithesis of “backing off.”22 The group urged black men, especially in prison, to display greater diligence in challenging white supremacy. Members of the group in Ohio and North Carolina endorsed a poem, “I Have Seen America,” that captured the New Afrikan position when it declared, “I do not qualify for justice. I was kidnapped from my / Native land, I saw Brother George and Malcolm killed / I have seen America.” Black On members also coauthored a letter urging prisoners and others to offer special support to captured black revolutionaries. “It is asked in Blackness[,] to progress materially as well as spiritually, that each of our brothers and sisters, comrades in the struggle[,] . . . start supporting our own.”23

The popularity of New Afrikan politics resulted from two factors. First, eleven members of the RNA, including cofounder Imari Obadele, were arrested in predawn raids on two of the group’s Jackson, Mississippi, headquarters on August 18, 1971, three days before George Jackson was killed.24 They spent most of the rest of the decade in various federal prisons, part of the expanding prison-made internal diaspora. Once in prison, Obadele and the other RNA activists continued their organizing. They used the strict conditions of their confinement as further proof of their political arguments. Obadele participated in the formation of a multiracial coalition of radical prisoners at the federal prison in Marion, Illinois, and wrote for Black Pride, a black nationalist prisoner magazine based there.25 In 1972, with its leaders in prison, the RNA released a legislative “Anti-Depression Program.” The title was similar to the manifesto of demands released during the previous year’s rebellion at Attica. Both writings demanded legislative changes while upholding self-reliance as a necessary practice on the way to self-determination. The RNA program was included in Foundations of the Black Nation, a book of Obadele’s prison writings that the RNA published in 1975. Together with the location of its author, the book’s title suggested that the experience of forced confinement was fundamental to bonding African descendants in the Americas as a national group.26

The RNA also grew quickly because it took up and extended an argument that resonated with prisoners. The notion of New Afrika as a nation formed by slavery extended the position that black prisoners were imprisoned by white supremacy long before they were incarcerated. The RNA’s ongoing work in prison and with prisoners gave this concept greater materiality than had been present when Malcolm X first popularized the metaphoric prison of racism. New Afrikans claimed that prisoners were on the front lines within the prison that held all black people. Staking their authority “by the grace of Malcolm,” New Afrikans extended his message that the black condition involved perpetual imprisonment. They spoke of the United States as imprisoning the New Afrikan nation, urged adherents to support prisoners’ struggles, and promoted prisoners as strategists for the developing black revolution.27

New Afrikan prisoners decried the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments as hypocritical. Central to New Afrikan political thought was the idea that the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, said to allow for due process, imposed the duties of American citizenship on former slaves without guaranteeing the rights that were supposed to accompany such civic status. The amendment, according to New Afrikans, offered but did not grant American citizenship. A study group of New Afrikan prisoners in Illinois determined that the Thirteenth Amendment, which outlawed slavery except as punishment for a crime, was part of an elite strategy to ensure the continuation of black bondage, now through prisons rather than plantations.28 New Afrikans argued that black people had never been given a chance to choose whether they wanted the citizenship that had been forced on them yet had never truly been granted. In opposing the constitutional basis of black incorporation into the American nation-state, New Afrikans identified the prison and slavery as mutually supportive elements of the United States.

The prison was central to the New Afrikan political imagination. From their cells, black prisoners became spokesmen (and, in a few instances, spokeswomen) in a struggle to “free the land!” New Afrikan prisoners argued that their incarceration reflected the ways that “U.S. imperialism” had denied the existence and thwarted the independence of New Afrika. Prisoners were therefore the black nation’s ambassadors to the Third World; their existence would certify the existence of a colony internal to the United States.

This line of reasoning was voiced most clearly from a prison cell in northern Illinois. Atiba Shanna (born James Sayles and later known as Owusu Yaki Yakubu) was, like many Illinois prisoners, from Chicago’s South Side. He went to prison in 1972, sentenced to two hundred years for the deaths of a North Side white couple.29 Shanna was already a politically conscious writer and a nationalist and was involved in the local Black Arts group, the Organization of Black American Culture. Other members of the group included poet Haki Madhubuti and novelist Sam Greenlee, author of The Spook Who Sat by the Door, a cult classic novel that told of a black nationalist who infiltrated the CIA to gain skills needed to teach guerrilla war to ghetto residents. In prison, Shanna became the most prolific and insightful New Afrikan theorist. He served for a time as the RNA minister of information. But his investment in New Afrikan politics extended beyond the governmental apparatus of the RNA.

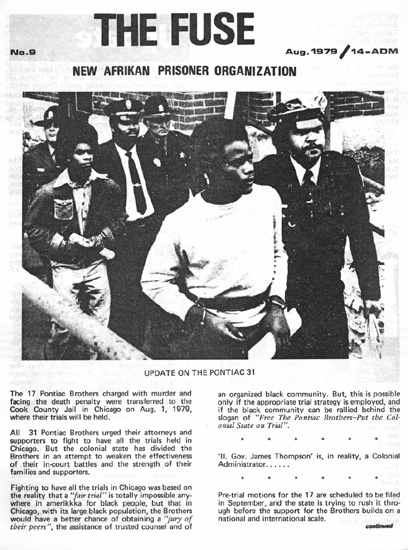

From the mid-1970s until his release from prison in 2004, Shanna worked to popularize New Afrikan ideas. With Bradley Abdul Greene, a former member of the Chicago Black Panther Party then incarcerated at Stateville, Shanna was the ideological force behind the Stateville Prisoners Organization and the New Afrikan Prisoners Organization (NAPO), which attempted to unite prisoner groups at several different Illinois facilities. NAPO formed in 1977 as a way to sharpen collectivity among prisoners and between prisoners and the urban communities from which they came. Within the Illinois prison system, NAPO led study groups, wrote articles, tried to foster unity among disaffected black prisoners, and worked to maintain connections to black organizing in Chicago and other big cities. Ultimately NAPO ceased being a prisoner group and became the New Afrikan Peoples Organization.30 According to Shanna, “Prisoners will play a significant role in the formation of a national, revolutionary, black political party and in the formation of a national, revolutionary, black united front.”31 That united front never materialized, but hints of it were visible through the rise of prison-based publications. Indeed, prisoner journalism and print culture were the central building blocks of black prison nationalism and the larger prison movement of which it was a part.

“REMOVE THE BARRIERS BETWEEN THE OUTSIDE AND INSIDE”

There is nothing inherently subversive about prisoner writings. Believing reading and writing to be therapeutic and educational—that is, rehabilitative—some prison administrators had allowed prisoners to produce newsletters as early as the 1950s. This “bibliotherapy,” as it was called, originated in the postwar spirit of prison reform that California symbolized nationally. These media, timid and apolitical products that reported mostly on prison happenings, were printed in-house and read predominantly by prisoners and staff.

As prisoners began to challenge their confinement in the late 1960s, their writings became more subversive in tone and method of distribution. Prisoners produced a number of covert publications, such as The Outlaw (1968, San Quentin), The Iced Pig (1971, Attica), and Aztlán (1970–72, Leavenworth). Radical prisoners worked alone or in small groups to create these publications, often acting surreptitiously and with minimal access to the tools of design. Radical newspapers on the outside occasionally reprinted some or all of these texts, but they were intended primarily to rally prisoners against guards.32

Prison-based black nationalist publications of the 1970s had a different magnitude and purpose. These publications spoke the language of Third World anticolonialism and used their own nationalist idiom. They provided a chance for prisoners to circumvent the prison by working with outside activists on writing and editing. They did not, as some had earlier, suggest that the revolution would come solely from within prisons. But they posited that as a result of their incarceration, prisoners were and ought to be providing some intellectual leadership for the black nation. These newspapers joined books by Malcolm X, George Jackson, and others as tools of literacy and political education. The publications sought to connect dissident prisoners amid the growing atomization caused by the increasing use of lockdowns and the declining significance of the written word after prison officials began installing televisions.33

These prisoner newspapers emerged on the coattails of the 1960s underground media and shared similar goals of education and agitation.34 They attempted to establish a united front among black prisoners while making alliances with Latinos and where possible white antiracist prisoners. Their primary purpose, however, was to establish connections between prisoners and outside supporters under the mantle of revolutionary nationalism. Overt dissent in the form of riots and strikes had become substantially harder, so prisoners turned to media as a way to foster unity and facilitate communication.

Publications were the lifeblood of black nationalist prison organizing, promoting a shared political understanding of the problems of confinement and the potentials of nationalism. California, Illinois, and New York remained central to the development of black prison nationalism, even though self-proclaimed New Afrikans could be found in prisons across the country. Prisons in those three states hosted at least eight regularly published newspapers and magazines steeped in New Afrikan politics and with an ongoing connection to prison issues: Arm the Spirit, Awakening of the Dragon, and Seize the Time (California); Black Pride, The Fuse (originally Stateville Raps), and Notes from an Afrikan P.O.W. (later Viva wa Watu) (Illinois); and Take the Land and Midnight Special (New York).

In politics as in real estate, location is everything. The three states where black prison nationalism most thrived were, not coincidentally, pivotal fronts in the war between the radical Left and the Far Right. Oakland, Los Angeles, New York City, and Chicago were home to the biggest chapters of the Black Panther Party as well as to a myriad of other progressive and revolutionary organizations. Each city was also a model laboratory for the shifting urban policies of a postindustrial age. Police brutality had been a perennial problem for radical groups and black communities in these and other big cities, but developments in these four cities in particular presaged the massive state investment in policing, imprisonment, surveillance, and privatization that has largely governed the United States since the early 1970s.35 Indeed, significant changes in Sacramento, Albany, and Springfield coincided with developments in Washington, D.C., and on Wall Street to tighten the interlocking connections among police, prosecutors, and prisons.

California gave the world Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, the high priests of punishment, along with a grassroots tax revolt that pitted white suburbs against increasingly black and brown cities through deeply racialized yet formally color-blind discourses.36 The Golden State garnered praise after World War II for its rehabilitative penology, but by the mid-1970s it was better known for an anti-Left backlash, heavy-handed policing, and indeterminate sentences. Los Angeles stood at the forefront of the increasing militarization of American police departments. The Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) team began there in 1966, partially in response to the rioting in Watts a year earlier. As a style of policing, SWAT teams combined the latest in military technology with good old-fashioned spectacle.

In 1974, the LAPD’s SWAT team staged a heavily armed and highly choreographed assault on the Compton house where members of the Symbionese Liberation Army, wanted for the murder of an Oakland school superintendent in November 1973 and the kidnapping of heiress Patty Hearst three months later, were hiding. After a shootout, police set fire to the house, burning to death the six people inside. All of it was televised. These dramatic killings were the most extreme spectacle of this heightened policing that saw members of California’s black and Latino populations stopped, frisked, harassed, and arrested in ever-larger numbers. By the early 1980s, these policing strategies buttressed a political economy of punishment that helped launch the biggest wave of prison construction in world history.37

Other states also ramped up their police powers and prison capacity. Nelson Rockefeller may have been the last liberal Republican of his day on certain issues, but he was a pioneer of mass incarceration and its racialized consequences. The New York governor refused to negotiate with the prisoners at Attica, preferring to end the rebellion with a disproportionate display of force. The deaths at Attica showed the government to be more invested in spectacular violence than prisoner militants ever were—and with much greater capacity to carry it out. Two years later, Rockefeller advanced Nixon’s war on drugs perhaps more than any other single figure through a panoply of laws (popularly known as the Rockefeller drug laws) that criminalized drug use, sale, or possession with steep prison sentences. New York’s war on drugs became a model for the national drug war, sweeping state legislatures with the allure of federal dollars to launch a new era of Prohibition backed by a strong carceral state.38

For its part, Illinois foretold the shape of prisons to come. As University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman and others found larger audiences receptive to an antistate free-market fundamentalism, a federal penitentiary in southern Illinois demonstrated that the state’s power was in fact growing rather than shrinking, at least with regard to punishment. The federal prison at Marion was built for ten million dollars in 1963. In 1972, the facility opened the first control unit prison with more than one hundred “problem inmates” (most of them black and Latino political prisoners) transferred from prisons around the country. Marion prison was a high-tech experiment in isolation and behavior modification, the most intense federal prison between the closure of Alcatraz in 1963 and the opening of the super-maximum security prison at Florence, Colorado, in 1994. Prisoners at Marion were subject to a battery of psychological abuses, including arbitrary punishment, complete isolation, and sensory deprivation. Prison officials hoped that this approach, which historian Alan Eladio Gómez has said “muddled commonplace distinctions between what constituted punishment, rehabilitation and torture,” would eliminate dissent.39 Though the experiment failed abysmally, resulting in lawsuits and a riot amid persistent lockdown, it became the basis for the control units and supermax prisons that began to comprise the new normal of American punishment.

As devised by Nixon, Rockefeller, and Reagan in accordance with proposals from conservative public intellectuals such as James Q. Wilson and Ernest van den Haag, “law and order” was a color-blind Trojan horse delivered to suburban whites in hopes that the trope of public safety in an era of white flight would promote a reactionary political agenda that, as Nixon said when discussing welfare reform, targeted black people without seeming to do so.40 Still, the call for more police and fewer drugs garnered support from many liberals and civil rights moderates, among others. It resonated with many moderates in the decaying urban landscape, including some long-standing civil rights advocates as well as a new urban elite moving into the city at a time when many who could do so were leaving. Both sets of individuals wanted a “cleaner” city. With the mainstream media increasingly emphasizing crime news, legitimate desires for public health and safety were easily subsumed into the bogeymen animating law-and-order discourse.41

As mainstream news outlets failed to report the consolidation of new forms of high-tech punishment, New Afrikan publications were among the only ways such information could reach the outside world. Most but not all of these papers were edited by prisoners and produced by outside supporters. Several other publications only printed one or two issues, were locally or regionally based, and/or were prison-related media not steeped in New Afrikan thinking. These publications include NEPA News (published by the New England Prisoners Association), CPSB Newsletter (put out by the Coalition for Prisoner Support in Birmingham, Alabama), and The Real Deal (produced by a collective of prisoners and nonprisoners in Indiana). Left-wing bookstores such as the Red Star North Bookstore in Portland, Maine, run by the Statewide Correctional Alliance for Reform, often served as clearinghouses for this information. Among the black publications that printed news and analysis of prison protest at this time were California’s Black Scholar and New York’s Black News (a publication of Queen Mother Moore’s organization, the East) as well as Jet magazine. Many of these periodicals covered ongoing cases involving well-known prisoners.42

What distinguished New Afrikan media, by and large, was their commitment to identifying the prisoner as ambassador of the captive black nation. The prison was so central to these publications that individual articles did not need to address imprisonment to conjure the prison. Whether calling for armed revolt or printing prisoner poetry, these periodicals documented the specter of prison in black life. Fiercely and often didactically political, they allowed prisoners to analyze society in public. The publications’ broad interests included Third World movements, the rise of black elected officials, law-and-order politics, jazz, theater, affirmative action, poetry, and the emergent blaxploitation genre.

Prisoners often affirmed their ethnic pride to legitimate their arguments. In 1973, for example, Midnight Special printed two letters from prisoners about blaxploitation. Under the headline “Black Movies and Twentieth Century Slaves,” both authors criticized the genre for perpetuating negative, propagandistic, and derogatory stereotypes about black men and women. One of the authors, imprisoned at Soledad, began the letter by establishing his good intentions: “I am writing to you, In Sincerity and Blackness, concerning my feelings of Miss Pamela Grier as an actress.”43 At Marion, prisoners writing for Black Pride critiqued black women’s beauty standards, printed poems in honor of Angela Davis, and reviewed Amiri Baraka’s plays.44

The nine members of the Black Cultural Society Awareness Program at Marion constituted the editorial group that produced Black Pride. Its motto was “Everything is political.” The short-lived journal lived up to its name and motto: four of the editors had adopted Swahili names, and its articles addressed topics ranging from “pitfalls to avoid in dealing with the South Africa question” to the “beauty of the black woman.”45 Black Pride featured trivia about black nationalist history—people, laws, organizations—along with Swahili vocabulary lessons. Its pages carried hopeful articles about building “BlkUnity” in Marion between prisoners who were in the Nation of Islam and those who were not; analyses of the mainstream media as institutions of racial capitalism; reviews of records and plays; and calls to action on behalf of the Republic of New Afrika or Angela Davis.46 The editors of Black Pride, as well as its contributors, brought Talmudic discipline to their attempts to interpret the words of Malcolm X and George Jackson.47

Black Pride exemplified the way that New Afrikan politics sprouted through the cracks of a federal penitentiary. The mimeographed periodical showed that the divisions between revolutionary nationalism and cultural nationalism, blurry on the street, could collapse entirely in prison. The erasure of these distinctions moved traditional cultural nationalism to the left (as seen from the journal’s overtly political disposition) and revolutionary nationalism to the right (as seen from its discussions of black women).

The gender politics of Black Pride were more retrograde than most prisoner publications of the time, which either expressed support for women’s liberation or ignored women altogether. Black Pride, however, revived the virgin/whore dyad that dominated Eldridge Cleaver’s still-popular Soul on Ice, which opened with the rape of black women and closed with a love letter to the “Queen-Mother-Daughter of Africa.”48 In the pages of Black Pride, Angela Davis received widespread praise as the princess of the black revolution. Poems encouraged her to “keep your faith in the Black race, for we’ll be doing all / we can to see that you win this case” and worried about her fate in an era where several black revolutionaries had been assassinated.49 Yet discussions of black women in the abstract often struck a different note, as authors proclaimed the need to protect black women from the violence of white hands and ideas. This theme could appear as reflexive self-criticism: “couldn’t really love you blk / woman / didn’t realize your nearest oppressor—me / projecting wite values from a blk / perspective.” But it could also go the other way, as in a review of Baraka’s Madheart that parroted the play’s misogynistic claims about the need for black men to reconquer black women from white standards.50

To have staying power, prisoner publications would need the coordinated support of outside organizations. In New York, such support came in the form of a monthly newsmagazine, Midnight Special, named after a southern black work song popularized by legendary blues musician Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter, who had been incarcerated himself. The train of the title carried prisoners to freedom. The idea for the paper emerged among the members of the New York chapter of the National Lawyers Guild after the Attica rebellion. Attorneys who had been doing prisoner rights work wanted to start a newspaper to address routine legal and health care matters. The NLG persuaded New Left activist Russell Neufeld, who had been aligned with the Weathermen’s faction of Students for a Democratic Society, to serve as the new publication’s managing editor. Neufeld then recruited help from assorted leftists, many of whom had been involved in Black Panther defense campaigns or supporting the Attica Brothers. As with most New Left and Black Power publications, no one involved had any professional journalism training; creating the periodical was a labor of love and political commitment.51

The magazine was based in the basement of the New York NLG’s office in the West Village. The first issue appeared in the fall of 1971. Within a few months, the publication was being produced by a collective of eight people, including two men who had recently been released after serving a combined total of twenty years at Attica. The other members of the collective, however, had only limited personal experience with the criminal justice system. Neufeld had served ninety days in the Cook County Jail after being arrested as part of an antiwar protest. Another member, Phyllis Prentice, worked at Rikers Island as a nurse and carried messages back and forth between imprisoned Black Panthers and activists outside. (She performed a similar role when she moved to San Francisco in the mid-1970s and worked at the jail there.)52

When Midnight Special began, the editors or other NLG members wrote all of the articles, but the number of prisoner contributions increased in each issue. Within a year, nearly all of the articles were written by prisoners, and circulation had topped three thousand. The editorial collective sent the paper directly to jails and prisons or distributed to groups and bookstores that supplied prisoners with reading material. While the paper made its way into many outside hands, it was based in prison. The editors mailed it to facilities that would accept it, while prisoners’ lawyers and friends smuggled it into facilities that would not.

The paper was a prisoner resource: NLG lawyers answered legal questions, and workers from the Health Revolutionary Unity Movement answered medical questions. But more than any particular legal or medical question, Midnight Special was a communication resource, helping prisoners retain connections to their families, friends, and supporters as well as prisoners at other institutions. The magazine provided both political sustenance and personal edification. Neufeld took part in a panel discussion in the mid-1970s with a recently released prisoner who had learned to read under the guidance of a fellow prisoner who was an avid reader of Midnight Special and used the paper to teach reading and critical thinking skills.53

With its authors scattered in prisons throughout the country, Midnight Special had a long reach. Attica remained a symbolic touchstone of prison radicalism for the paper, whose editors and publishers were involved in various defense efforts for the prisoners there. But the paper had a national scope. It regularly printed articles by or about prisoners in Virginia, North Carolina, Maryland, Georgia, Massachusetts, California, and Washington, D.C., and organizations as diverse as the NAACP, the Black Guerrilla Family, the Black On Vanguards, and the prison chapters of the Black Panthers and the Young Lords. Midnight Special also featured prison struggles anywhere on the U.S. eastern seaboard and political prisoners worldwide. Of particular interest was the case of five members of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party who were imprisoned for their dramatic attacks on U.S. authority in the 1950s and who became a lodestar for the rebirth of Puerto Rican revolutionary nationalism in the 1970s.54

In Midnight Special, prisoners wrote not only about their own prisons but also about their comrades in other prisons and about the metaphoric prisons that held captive the United States and the larger black world. Each issue featured a combination of essays, news, poems, graphics, and rants as well as reprints of petitions that prisoners had filed against their institutions or reprints from other prisoner publications. Midnight Special showcased the theoretical, strategic, and creative writings of hundreds of prisoners as well as drawings and other artwork.55

The paper sought to facilitate coalitions among prisoners at different facilities and between prisoners and social movements. While Midnight Special was oriented toward prisoners themselves, its editors saw a special role in securing public attention for prison struggles. “Outside support of inmate struggles is indispensable if the type of repression that occurred at Attica is not to be repeated,” the editors declared, affirming their intention to “remove some of the barriers that exist between the outside and inside.”56 The paper walked a fine line between publicity and anonymity: to avoid diverting attention from the writings of imprisoned intellectuals who at times had to remain anonymous to avoid repercussions, the editors, too, remained anonymous. Anonymity allowed the paper to print prisoners’ honest appraisals in which they described their confinement and the painful divisions, generational as much as spatial and emotional, it caused.

An anonymous prisoner at Soledad penned a poignant poem, “Only the Blues Is Authorized,” in which he expressed his fears that those who had previously known him would no longer recognize him: “I would look strange to them / their soldier son / for I would look like the concrete / I’ve had so long next to my skin.”57 This poem appeared next to a Pennsylvania prisoner’s ode to the songs of Billie Holiday and lamented the prisoner’s invisibility to the society that produced him. Imprisonment now produced a sense of loss and a passion for justice. The blues signified the possible coexistence of love and hate, passion and detachment—the prison and a world beyond it. Other contributions to Midnight Special were less nuanced. A poem by a prisoner in Lorton, Virginia, declared prisoners to be the most ethical sector of society: “Wake-up Amerika if you expect to remain. / You see Amerika the solutions are under / George Jackson names.”58

Like so much of the radical Left by the mid-1970s, Midnight Special joined innovation and isolation. It was a powerful catalog of prisoner activism during a time of growing public disinterest in the far Left. The paper presciently foretold the rise of mass incarceration as a weapon of class stratification that all but erased young black people from society as workers, organizers, and voters. It shined a light on organizing endeavors by unionists and nationalists, communists and anarchists, and the unaffiliated. Midnight Special provided prisoners with a venue in which to discuss political strategy while affording them a chance to engage in dialogue with one another. The paper recognized that struggle occurred among women and gay prisoners, denaturalizing the heterosexual black male prisoner as the sole politically active force in prison—even if black men remained the dominant focal point of the paper as well as of the prison.

Midnight Special became more rhetorically overburdened as American prisons became more racially overdetermined. According to sociologist James Jacobs, “By 1974, a nationwide census of penal facilities revealed that 47 percent of prisoners were black. In many state prisons blacks were in the majority.”59 Midnight Special described prisons as a staging ground for radical protest, effectively putting the prison on the same plane as struggles against British colonialism, Israeli settlement, or South African Bantustans in the production of racial consciousness. The editors described the prison as an institution that “touches us all” yet does so in unequal ways.60 Even with the stodgy Marxist rhetoric or calls for armed struggle that increasingly characterized the paper after 1974, when several founding editors departed, the paper’s voice came from the future, warning of the social costs of locking up more and more people in cages.

The connections prisoners established through Midnight Special and similar endeavors were useful in other ventures, campaigns that would bring prisoner ideas to the global arena. Alongside a host of stateless nations at the time, black prison nationalists turned to the United Nations as a possible avenue of redress—both for their specific imprisonment and for their broader confinement in the United States. Following from the strategy Malcolm X advocated toward the end of his life, black nationalists viewed international law, represented by the United Nations, as the best possibility for a neutral or perhaps even supportive (in light of the era’s embrace of decolonization) hearing for their grievances. Appealing to the UN revealed that this black nationalist vision was global. It rejected the American state in favor of identification with the Third World and its dreams of a future autonomous government. These prisoners hoped that embarrassment in the international arena would force the United States to change. Even more than the UN as a body, these campaigns were addressed to the UN as a symbol: the biggest international institution concerned with human rights, the UN meant a rejection of U.S. authority and the possibility for alternate alliances. For that reason, Georgia Jackson petitioned the United Nations in 1972 for an investigation into the circumstances of her son’s death, Marion prisoners appealed to the UN for relief, and poet-musician Gil Scott-Heron sang of appealing to the UN for reparations.61

Black radicals had focused on the United Nations as a venue almost since the institution formed. In 1951, the Civil Rights Congress authored and delivered a petition, “We Charge Genocide,” to the UN. The text was written by black communist William Patterson and aided by the participation of performer-activist Paul Robeson. The United Nations never responded to the original petition, but it was reprinted in its entirety in 1970. In an introduction to the new edition, Patterson wrote that the petition sought “to expose the nature and depth of racism in the United States; and to arouse the moral conscience of progressive mankind against the inhuman treatment of black nationals by those in high political places.”62 Patterson and his wife, Louise Thompson Patterson, continued to organize at the intersections of communism and black liberation. As with Queen Mother Moore and other black communists involved in the Scottsboro Boys defense campaign, the Pattersons served as mentors for the New York Black Panther Party and other black militants from the city. Unlike Moore, the Pattersons were party leaders; William had headed the International Labor Defense, the Communist Party’s mid-twentieth-century apparatus for supporting those facing political repression. The Pattersons’ party leadership roles left them well equipped to tutor young militants in political strategy. Rooted in an internationalist perspective, the Pattersons helped circulate the idea of genocide as a conceptual framework for black antiracist struggles. They also identified the United Nations as a potentially receptive means of bringing these concerns to a global audience.63

In the late 1970s, the UN became the focus of several prisoner appeals. Black prisoners submitted petitions criticizing black imprisonment from slavery to the present; all of these documents identified George Jackson as an iconic figurehead. As with the New Afrikan newspapers, these prisoner appeals to the United Nations were less about prison conditions than about establishing the legitimacy and international standing of the black nation. Located behind bars, the authors of these petitions used their status to demonstrate the carceral framework of black resistance to American racism. Owing to what one prisoner described as “the extreme concentration of oppression” in prisons, people held there were the most obvious choice to launch a campaign oriented toward what one prisoner called “the ‘politics of anti-oppression’ . . . presented within the context of the class and national liberation struggle.”64

The New Afrikan Prisoners Organization initiated one such effort in 1977. The petition, “We Still Charge Genocide,” clearly alluded to its 1951 predecessor. Less an appraisal of contemporary racism, the new petition was a challenge to the moral and juridical basis of American power based on a study group at the Stateville prison that reexamined the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. In each of the three amendments held up as harbingers of racial progress, prisoners found proof of white supremacy’s retrenchment. With the ink having dried on landmark civil rights legislation, these prisoners looked to an earlier period of legislating antiracism. And if the laws to end slavery only reinscribed white supremacy, what hope was there for laws designed to end Jim Crow? The fact that the Stateville prison population by this point was 75 percent black showed that the emerging carceral regime continued a long history of black disenfranchisement.65

As prisons became more severe, New Afrikan prisoners became more globally minded. From a prison in Atlanta, RNA president Imari Obadele released a letter to Fidel Castro and the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization to request a prisoner exchange whereby the United States would release seventeen New Afrikans to Cuba in return for an equal number of “counter-revolutionaries now in Cuban jails.”66 This request situated New Afrika as a Third World nation akin to Cuba. Inspired by these prisoner efforts, outside organizations also took it upon themselves to contact the United Nations about the question of prisons in the United States. The National Conference of Black Lawyers, the National Alliance against Racist and Political Repression, and the Commission for Racial Justice for the United Church of Christ filed a petition on December 11, 1978, the twenty-fifth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Human Rights. The petition, given to the UN Commission on Human Rights and the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, detailed human rights violations in the incarceration of dozens of black, Puerto Rican, Chicano, and indigenous political dissidents. It also detailed government misconduct against these social movements as recently reported through the Church Committee hearings. As a result of that petition, the International Commission of Jurists sent a representative to visit select U.S. political prisoners.67

The petition submitted by the National Conference of Black Lawyers developed out of petitions attempting to resurrect political protest through a strategic focus on black prisoners. Beginning in 1976, Jalil Muntaqim initiated a prisoner petition to the UN from San Quentin. Muntaqim (originally known as Anthony Bottom) had been arrested in San Francisco in 1971, when he was a headstrong nineteen-year-old member of the Black Panthers accused of participating in a shootout with police in retaliation for George Jackson’s death. In 1972, he was transferred to New York City to stand trial with four other former Black Panthers in the death of two police officers in a BLA-related shooting there. While awaiting trial, Muntaqim was confined in a special area of the Queens House of Detention whose residents also included longtime political activists Jamil Al-Amin and Muhammad Ahmad. The two elder black revolutionaries had already converted to Islam; after more than four months, they had persuaded Muntaqim, then a communist, to adopt a monotheistic faith. Muntaqim’s first trial ended in mistrial, and prosecutors dropped charges against two of the defendants. In 1975, Muntaqim, Herman Bell, and Albert Nuh Washington were convicted in a second trial, and Muntaqim was sent back to San Quentin to complete his California sentence.

Back in the Adjustment Center, Muntaqim was “locked in a cell between Brother Ruchell Magee and Charles Manson.”68 Not far from him were the San Quentin 6, Black Panther Geronimo Pratt, and Symbionese Liberation Army members Bill Harris and Russell Little. Supporters had encouraged him and other AC prisoners to write articles and statements as a way to dialogue with movements outside. Muntaqim drafted the UN petition in response to a letter in which the National Committee for the Defence of Political Prisoners proposed an international campaign to free activists imprisoned with lengthy sentences. The New York–based committee was an outgrowth of the Panther 21 defense committee. Its most well-known member was Yuri Kochiyama, a friend of Malcolm X and the only nonblack citizen of New Afrika. Muntaqim wrote his proposal and shared it first with Magee. After that, Muntaqim sent it to the second floor to be reviewed by Pratt. With his approval, Muntaqim sent the petition draft to the committee. But the organization was too bound up in supporting various prisoners to launch any campaign.69

As he waited for a response, Muntaqim was transferred out of the Adjustment Center into general population. A prisoner there—Muntaqim knew him only as Commie Mike—introduced him to the United Prisoners Union, a small, more nationalist offshoot of the Prisoners Union. With connections to prisoners in two dozen states, the UPU took on Muntaqim’s petition campaign and facilitated communication among the prisoners involved. Muntaqim’s effort gathered twenty-five hundred signatures from prisoners across the country. The final version called for an international investigation into American prisons as sites of discrimination and genocide. Attorney Kathleen Burke, who had worked with Amnesty International, filed the petition as a UN document in Geneva.70

This support, while impressive, meant little more than verbal or written affirmation by prisoners. They were not actively involved in conceiving the campaign, although some mobilized to help it succeed. In New Jersey, for example, a group of prisoners established themselves as the August 21 Prisoners Human Rights Coalition. The petition campaign connected prisoners with one another, through organizations such as the Prairie Fire Organizing Committee (PFOC), the United Prisoners Union, and, briefly, the African People’s Socialist Party. The PFOC, a public organization of antiracist whites that was formed by the clandestine Weather Underground in 1975, was critical in facilitating prisoner communication in California, Illinois, and New York. The African People’s Socialist Party was a black nationalist group whose tenure with Arm the Spirit was marked by divisiveness and hostility that ultimately led to the paper’s demise when party members tried to incorporate it into their own newspaper, the Burning Spear.71

Networks of communication also provided the basis for some international attention to the issues motivating the petition, even if the petition itself did not attract notice. According to Muntaqim, in the summer of 1978, a reporter for the French socialist newspaper Le Matin asked U.S. prison organizers how he could help their campaign. Via intermediaries, Muntaqim suggested that the reporter ask the U.S. ambassador to the UN, Andrew Young, whether the United States had any political prisoners.72 Young, a veteran of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the first African American to represent the country before the world body, answered that “there are hundreds, perhaps even thousands of people I would call political prisoners.” Although he did not name any particular individuals, Young’s comments, delivered in France in the context of a discussion about the jailing of Soviet dissidents, provoked fierce opposition back home from politicians who insisted that the United States had no political prisoners. U.S. representative Larry McDonald, a Georgia Democrat, introduced a resolution in the House calling for Young’s impeachment. Though his resolution was soundly defeated (293–82), Young was widely criticized, and he apologized for his remark. He was eventually forced to resign after a succession of public relations blunders.73

Muntaqim welcomed the Paris publicity. He asked Sundiata Acoli, another former Panther turned New Afrikan, who was imprisoned in New Jersey, to call for a protest in New York. Acoli, a former employee of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration who had tutored astronaut Neil Armstrong in math, was by this time serving life in prison. Acoli had been one of the defendants in the Panther 21 trial (1969–71), in which the government prosecuted the party’s New York leaders on a series of spurious charges designed to break the chapter and separate it from the national office. Thirteen of the defendants coauthored Look for Me in the Whirlwind, a collective autobiography, while in jail and awaiting trial. Like many of the Panther 21, Acoli went underground after the acquittal. In 1973, he was arrested after a shootout on the New Jersey Turnpike in which fellow BLA member Zayd Shakur and a New Jersey state trooper were killed. Assata Shakur was shot and arrested; Acoli initially got away but was caught two days later.

Acoli’s participation in Muntaqim’s plan made the effort bicoastal. Through a coalition of nationalist-oriented groups, Acoli called for a protest at the Harlem State Office Building. The groups tried to coalesce as the National Prison Organization to do community organizing regarding prison issues and prisoner organizing regarding dynamics in outside communities. This effort, however, quickly shattered. A demonstration at the UN as part of the prisoner petition was moved to the State Office Building, and no further organization materialized.74

This bicoastal protest, launched by two prisoners with limited outside contact, flowed from the Black Liberation Army’s attempt to turn prisons into what Acoli called strategic “instruments of liberation.”75 The BLA was a clandestine and largely decentralized military grouping whose members were accused of participating in a series of attacks on police officers and drug dealers that were allegedly financed with bank robberies. By the time Acoli called for the Harlem demonstration, the BLA was suspected in dozens of shootings of police officers nationwide. The BLA is often described as comprising those Panthers who were loyal to Cleaver after his split with Newton. While many who built the black underground shared Cleaver’s insurrectionary predilections, the group was more loyal to traditions of revolutionary nationalism (including its emphasis on self-defense) common throughout the rural South and in New York City’s black political history. Not surprisingly, then, many acknowledged or alleged BLA members were either southern-born or members of the New York chapter of the BPP or both. As the RNA supplanted the Panthers as the dominant expression of black revolutionary nationalism in the 1970s, several New Afrikans also counted themselves among the BLA’s ranks.76

In the mid-1970s, with many of its members incarcerated, the BLA endeavored to use the prison as a cadre training school. Convicted BLA members tried to subvert the prison by any means necessary, including escape attempts and intellectual study. Both approaches expressed an audacious commitment to freedom. Their pedagogy and their marronage fit within a black radical tradition of living within but beyond American society. Inspired by contemporary international prisoner struggles—especially the September 1971 escape of more than one hundred Uruguayan Tupamaro guerrillas who tunneled their way out of prison and back into the armed underground—BLA members made several daring attempts at escape. Most failed, and in a couple of cases, the escapees died, but a few succeeded, at least temporarily.

Safiya Bukhari was a middle-class black woman who joined the New York City Panthers to support their community programs. She worked on the Black Panther newspaper and later the Cleaverite offshoot, Right On! She was arrested in December 1973, accused of plotting to break accused BLA members out of the city’s Tombs detention facility. Cleared of the Tombs conspiracy but subpoenaed to testify in a grand jury investigating clandestine black radicalism, Bukhari went underground until she was arrested after a grocery store shootout in Virginia in 1975. She was sentenced to forty years in prison but escaped in 1976. When she was apprehended and tried for the escape, she used her trial to challenge the abysmal medical treatment in prison. Bukhari had fibroid tumors in her uterus that prison officials refused to remove until after her escape.77

Others followed her example. Philadelphia Black Panther Russell Shoatz was arrested for the death of a police officer in 1972. He escaped from a Pennsylvania prison in September 1977 and remained at large for a month, earning the sobriquet “Maroon,” in honor of nineteenth-century escaped slave rebels. Several other escape attempts in the mid-1970s by people connected to the BLA or related groups were aborted or failed, and at least two people died in their bids for freedom. The most successful BLA escape came on November 2, 1979, when Assata Shakur escaped from a New Jersey prison with the help of a BLA unit. She lived underground in the United States for several years before taking up residence in Cuba as a political exile, where she remains.78

Alongside and outlasting the escape attempts, BLA members also turned to political education. BLA members led political education classes in prisons around the country. In 1975, members of the heretofore decentralized guerrilla group established a coordinating committee with members both in and out of prison and began publishing a newsletter. Two years later, the coordinating committee distributed a 150-page study guide to imprisoned supporters with the goal of solidifying BLA politics among new recruits and existing members alike. It was a primer on revolutionary nationalist thought, with sections on the black nation, dialectical materialism, democratic centralism, political economy, and other Marxist-Leninist precepts. In addition to theoretical essays on these subjects, the guide included a “political dictionary” that introduced neophytes to the revolutionary nationalist lexicon. Drawing on the experience of BLA members in court and the media, the study guide objected to elite attempts “to make the words terrorism and revolutionary synonymous.”79 The study guide distanced the BLA from the “indiscriminate violence and murder” of terrorism. It was part of a larger critique of the ways that terrorism was becoming an increasingly significant keyword of Western governance—a sign of a dawning age of violent extremes.80

The guide and the coordinating committee as a body represented the BLA’s greatest centralization of structure and ideology; some members found it to be overreaching. Yet even members who distanced themselves from these developments participated in diverse political education projects inside.81 The circulation of the study guide and the UN petition and the landscape of prisoner peer mentorship demonstrate the existence of a network for distributing information, with nodes both in and out of prison. This network proved critical to establishing the distribution networks for prisoner media, such as Arm the Spirit. The paper began as Voices from within San Quentin, a mimeographed newsletter that reported on prison conditions.82

Voices offered a way to foster communication among prisoners in the increasingly isolated world of San Quentin—compartmentalization was one of the defining features of the newly emerging penal environment—while continuing to provide first-person commentary on prison conditions for Bay Area prison activists. Voices began in the San Quentin Adjustment Center in the fall of 1977, with contributions from several of the unit’s political prisoners. Funding problems precluded its printing until that winter, and six months later, it made the transition from a monthly newsletter on prison conditions to a quarterly newspaper of prisoner reporting on anticolonial movements around the world. The change was ambitious, turning a local newsletter into a national publication.