Chapter 2

Paul Robeson: crossing over

One ever feels his twoness – an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

W. E. B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk

In the jargon of the contemporary pop music business, a cross-over star is one who appeals to more than one musical subculture; one who, though rooted in a particular tradition of music with a particular audience, somehow manages to appeal, and sell, beyond the confines of that audience. Dolly Parton, Gladys Knight, Paul McCartney are recognisably country, soul and rock performers respectively, but they have a following among people who are not especially into those kinds of music. While having this wider appeal, they are still rooted in the particular musical subculture that defines them – in crossing over, they don't lose their original following. Or not too much of it.

The term cross-over, in this sense, did not exist when Paul Robeson was a major star, but, at least between 1924 and 1945, he was very definitely an example of it.1 His image insisted on his blackness – musically, in his primary association with Negro folk music, especially spirituals; in the theatre and films, in the recurrence of Africa as a motif; and in general in the way his image is so bound up with notions of racial character, the nature of black folks, the Negro essence, and so on. Yet he was a star equally popular with black and white audiences. There were other black singing stars as, if not more, popular than he in the twenties and thirties – Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters, Cab Calloway, Billie Holiday – but none of these quite established the emblematic or charismatic position, for blacks and whites, and in more than one medium, that Robeson did. How did he manage this?

Some would argue that his achievements were so unarguably outstanding that he had to be recognised. Certainly there is no gainsaying those achievements – a brilliant academic record at Rutgers University (1915–19), where he was the only black student at the time and only the third ever to have been admitted, and at Columbia graduate law school (1920–1), where he was again the only black student; a great football player, the first black player ever selected to play for the national team (the All-Americans) from the university teams, all the more remarkable, according to Murray Kempton, for being from Rutgers, a less prestigious university (Kempton 1955: 238); certainly the best known and most successful male singer of Negro spirituals, in concert and on record, and always highly acclaimed critically; the performer of what has been called the definitive Othello of his generation (‘The best remembered Othello of recent decades’, wrote Marvin Rosenberg (1961: 151)) and in the longest running Shakespeare production in Broadway history (1943–4); one of those performers who has made one of the standards of the show business repertoire, ‘Old Man River’, wholly identified with him, so much so that he was himself often referred to as Old Man River; singer of the hugely successful patriotic ‘Ballad for Americans’ (1939) that the Republican party adopted for their National Convention in 1940; rapturously received in the theatre, particularly in The Emperor Jones (New York 1924, London 1926, Berlin 1929), All God's Chillun Got Wings (New York 1924, London 1933), Show Boat (London 1928, New York 1932) as well as Othello (London 1930, New York and US tour, 1943–5, Stratford-on-Avon 1959); and if nothing in his film career quite matches up to all that, still he was big enough to be billed outside a London cinema for the première of Song of Freedom 1936 as ‘GREATEST SINGING STAR OF THE AGE’ and worked with the most important black film-maker of the time, Oscar Micheaux (in Body and Soul 1924), with the avant-garde group surrounding the magazine Close-Up (Borderline 1930), in a lavish Hollywood musical (Show Boat 1935) and in a series of popular and, shall we say, for the most part decent British films of the thirties, as well as narrating a number of documentaries, including Native Land 1941 by Frontier Films and, outside our period, Song of the Rivers 1954 by Joris Ivens.

Yet such a list of achievements does not really explain his stardom. Whilst I don't want to diminish his talent or effort, this list is for the most part a statement of the fact that he was highly acclaimed, very popular, in other words, a star. But why were these achievements of so much interest to so many people? How were his remarkable qualities also star qualities? How and why were these the qualities of the first major black star?

We need to get the question right. How did the period permit black stardom? What were the qualities this black person could be taken to embody, that could catch on in a society where there had never been a black star of this magnitude? What was the fit between the parameters of what black images the society could tolerate and the particular qualities Robeson could be taken to embody? Where was the give in the ideological system?

Yet another way of putting it might be – what was the price that had to be paid for a black person to become such a star? Harold Cruse, the subtlest critic of both Robeson and the Harlem Renaissance with which he was associated, argues that from the perspective of black politics and black consciousness the price was too high. He finds Robeson too integrationist, too concerned with adapting himself to white cultural norms, too far removed from the real cultural concerns of black people, and too little aware that cultural development is not a thing of the spirit alone but is rooted in material conditions, the necessities of funding and support usually absent in black communities (Cruse 1969, 1978). Likewise, Jim Pines (1975: 32) suggests that Robeson's work is a ‘largely individualist and generally mystifying protest … [that] seems to substantiate the ineffectualness of individualist forms of protest against cultural exploitation by the media’; and Donald Bogle (1974: 98) even argues that Robeson was not only individualist in Pines’ sense of an isolated individual but in the sense of self-seeking; ‘No matter how much producers tried to make Robeson a symbol of black humanity, he always came across as a man more interested in himself than anyone else’.

The figure of Robeson still sets off argument about images of black peoples, and there is still a striking disparity in the different ways he is perceived. I am confining myself to the period in which Robeson was a cross-over and major star, roughly 1924–45, when the politics are less explicit and explosive than afterwards. What particularly interests me is the way that Robeson's image takes on different meanings in this period when read through different contemporary black and white perspectives on the world. There are different, white and black, ways of looking at or making sense of Robeson, but it would be a mistake to think that the white view is the one that stresses achievement, the black the one that stresses selling out. To set against Cruse, Pines, Bogle and the other black writers, there is Paul Robeson: The Great Forerunner, a book of articles and tributes, produced by the radical black magazine Freedomways (Freedomways editors, 1978), as well as countless celebrations of Robeson by black people throughout his career. Likewise, one can find – less easily, it is true – white writers quick enough to point to his artistic limitations or, like Murray Kempton (1955: 259), to deny his significance as an embodiment of black people: ‘There was absolutely nothing between him and the people for whom he affected to speak’.

Equally, in speaking of different, white and black perspectives, I don't imply that black people saw him one way and whites the other. What I want to show is that there are discourses developed by whites in white culture and by blacks in black culture which made a different sense of the same phenomenon, Paul Robeson. There is a consistency in the statements, images and texts, produced on the one hand by blacks and on the other by whites, that makes it reasonable to refer to black and white discourses, even while accepting that there may have been blacks who have thought and felt largely through white discourses and vice versa.

The difficulty of this argument is not so much theoretical as in discerning the difference between black and white discourses in relation to Robeson. The difference is not obvious in the texts, and that is part of the explanation of how Robeson's cross-over star position was possible. For much of the time it could seem that the black and white discourses of the period were saying the same thing, because they were using the same words and looking at the same things. Robeson was taken to embody a set of specifically black qualities – naturalness, primitiveness, simplicity and others – that were equally valued and similarly evoked, but for different reasons, by whites and blacks. It is because he could appeal on these different fronts that he could achieve star status.

All the same, Robeson was working, particularly in theatre and films, in forms that had been developed, used and understood in predominantly white ways. In appearing in white plays and films, Robeson already brought with him the complex struggle of white and black meanings that his image condensed – but what happened to those meanings? Just by being in the plays and films, some of those black meanings are registered – but they are part of a broadly white handling of him, and this is significant not so much at the level of script and dialogue, as at the level of various affective devices that work to contain and defuse those black meanings, to offer the viewer the pathos of a beautiful, passive racial emblem.

The strategies of the white media worked to contain Robeson, but only worked to. How he was handled by the media is conceptually distinct from how audiences perceived him. The media might reinforce white discourses that intended to contain what was dangerous about black images in general, but by registering the black meanings in his image they also made these widely available, for use by black people. There is plenty of evidence of the impact that Robeson had on black audiences, but James Baldwin's notion of the way that Robeson (and other black stars) could work against the grain of his films suggests, at least, how a black viewer could see it that way, and with the force of ‘reality’ and ‘truth’:

It is scarcely possible to think of a black American actor who has not been misused: not one that has ever been seriously challenged to deliver the best that is in him … What the black actor has managed to give are moments, created, miraculously, beyond the confines of the script; hints of reality, smuggled like contraband into a maudlin tale, and with enough force, if unleashed, to shatter the tale to fragments … There is truth to be found in … Robeson in everything I saw him do.

(Baldwin 1978: 103–5)

It is the range of potential reading, black and white, in the context of an overall white media handling of Robeson that is the subject of this chapter.

ESSENTIAL BLACK

Paul Robeson was widely regarded as the epitome of what black people are like. People felt that they could see this in the way he stood in concert, ‘tightening his broad shoulders to bear a load of agonised entreaty, casting the outlines of his head into a sort of racial stereotype’ (Sergeant 1926: 196), or hear it in his voice – ‘it was Mr Robeson's gift to make [the spirituals] tell in every line … they voiced the sorrows and hopes of a people’ (New York Times of his first concert, 19 April 1925). Ollie Harrington's (1978: 102) memories of a black ghetto upbringing, in the Bronx and then in Harlem, equally testify to how deeply racially significant Robeson was felt to be, an example of the fact that black people were capable of achieving what whites could and also someone whose singing ‘gripped some inner fibres in us that had been dozing’.

A similar feeling is evoked by Eslanda Goode Robeson in her 1930 biography:

Paul Robeson was a hero: he fulfilled the ideal of nearly every class of Negro. Those who admired intellect pointed to his Phi Beta Kappa key; those who admired physical prowess talked about his remarkable record. His simplicity and charm were captivating; everyone was glad that he was so typically Negroid in appearance, color and features … He soon became Harlem's special favorite, and is so; everyone knew and admired him … When Paul Robeson walks down Seventh Avenue … it takes him hours to negotiate the ten blocks from One Hundred and Forty-Third Street to One Hundred and Thirty-Third Street; at every step of the way he is stopped by some acquaintance or friend who wants a few words with him.

(Robeson 1930: 67–8)

This passage is a major moment in the authentication of the Paul Robeson image. It authenticates his image as the Negro man par excellence by showing that it is based in grass-roots approval in the heartland of urban black America, Harlem; and that is itself authenticated by being recounted by his wife. (At the level of popular hagiography, no niceties about spouses as unreliable witnesses intrude.) Eslanda's biography was a basis for much of the subsequent writing about Paul – this 143rd to 133rd story recurs endlessly, for instance.

The early recognition of Robeson as the incarnation of blackness was developed in his subsequent career. He played or was associated with many of the male heroes of black culture. He sang ‘John Henry’ in concerts and on records, and appeared in 1940, albeit briefly due to illness, in Roark Bradford's play about that more or less mythical worker hero of the 1870s. In 1941 he recorded, with Count Basie, ‘King Joe’, a tribute to Joe Louis, the most celebrated and successful of black boxing champions, and himself very much seen as the pride of his race (see Levine 1977: 429ff). He had, moreover, already played a boxer, a kind of generic black hero figure, in Black Boy in 1926. He played the lead in C. L. R. James's play Toussaint L'Ouverture in London in 1936, and was to have played in Sergei Eisenstein's film based on the revolutionary leader. There are echoes of Shine, the legendary black stoker on the Titanic who saw trouble ahead and swam an ocean to safety (Levine ibid.: 428), in Robeson's role as Yank in The Hairy Ape 1931 and the scene in the boiler room in the film of The Emperor Jones 1933. There is a portrait of Booker T. Washington behind the happy ending grouping of Robeson (as Sylvester) with wife and mother-in-law in Body and Soul 1924, and he was associated with the other major black intellectual leader of the times, W. E. B. DuBois, in public appearances at numerous meetings and rallies.

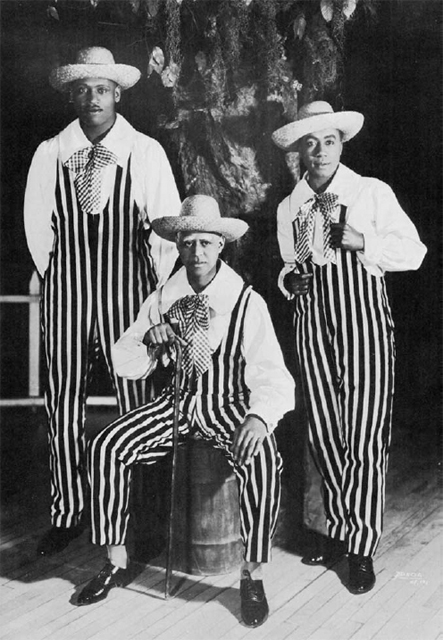

If he played or was associated with the heroes of black culture, he also played the stereotypes of the white imagination – Lazybones (the role in Show Boat), smiling Sambo (the ads for Show Boat (Figure 2.1), Bosambo in Sanders of the River 1934), variations on the plantation/sharecropping Jim Crow (Shuffle Along (Figure 2.2) 1920, Voodoo 1922, Tales of Manhattan 1942), black nobility (Song of Freedom 1936, Big Fella 1937), creature of the ghetto (Rosanne 1924, Body and Soul 1924; All God's Chillun Got Wings 1924, Crown in Porgy and Bess 1927, The Emperor Jones) and brute (Crown, Brutus Jones, Voodoo, Black Boy, The Hairy Ape, Basalik 1935, even Othello and Stevedore 1935) – to name but a few.

Small wonder then that Robeson should be so identified as the representative of blackness. Apart from the brute stereotype, these images of blackness, of Paul Robeson's blackness, were, whatever we may think about them now, affirmatively valued in the discourses of the period. Robeson represents the idea of blackness as a positive quality, often explicitly set over against whiteness and its inadequacies.

Typical of the general view of blackness that Robeson represented are statements like the following, from a white enthusiast for black culture:

It is … the feeling for life which is the secret of the art of the Negro people, as surely as it is the lack of it, the slow atrophy of the capacity to live emotionally, which will be the ultimate decadence of the white civilised people.

(Mannin 1930: 157)

Figure 2.1 Advertisement for Show Boat (film) 1936 (Miles Kreuger)

Such sentiments are part of a general revulsion with contemporary industrial society, of which Mabel Dodge's (1936: 453) words are typical:

America is all machinery and money making and factories. It is ugly, ugly, ugly.

Figure 2.2 Paul Robeson (left) in Shuffle Along (Paul Robeson Jr)

(Dodge was the patron of the Greenwich Village circle that had close links with the artists of the Harlem Renaissance.) Much of the work Robeson was associated with, and especially Eugene O'Neill’s dramas, plays on this opposition of basic black and white racial/cultural differences. The stage directions for All God's Chillun Got Wings spell it out quite precisely:

A corner in lower New York … In the street leading left, the faces are all white; in the street leading right, all black. It is hot spring … People pass, black and white, the Negroes frankly participants in the spirit of spring, the whites laughing constrainedly, awkward in natural emotion. One only hears their laughter. It expresses the difference in race.

(Act One, Scene 1).

John Henry Raleigh (1965: 110) notes of the black/white symbolism of The Hairy Ape,2 and particularly the central scene between ‘the terrified slender white-skinned, white-clad Mildred and the black, half-clad, muscular brute, Yank’, that it suggests a ‘familiar theme in the American racial situation … namely, that black stands for animal vitality, while white signifies frayed nerves’.

These are all positive evaluations of blackness by whites, but one can find similar statements about blackness by black writers. The words are not exactly the same, and behind minor differences in wording lie very significant differences in understanding, but they seemed to be saying the same thing. The locus classicus of the black view of blackness is The New Negro, a collection of essays edited by Alain Locke and published in 1925, which is often seen as the manifesto of the Harlem Renaissance. Whatever the topic, the same kind of evaluation of black (or, as they prefer it, Negro) art and culture recurs. Compare Ethel Mannin's ‘Negro gift for life’ and ‘atrophy of white civilisation’ with Albert C. Barnes on Negro art:

[Negro art] is a sound art because it comes from a primitive nature upon which a white man's education has never been harnessed … the most important element … is the psychological complexion of the negro … The outstanding characteristics are his tremendous emotional endowment, his luxuriant and free imagination … The white man in the mass cannot compete with the Negro in spiritual endowment. Many centuries of civilisation have attenuated his original gifts and have made his mind dominate his spirit.

(Locke 1968: 19–20)

Or compare Mabel Dodge's disgust at industrial, money-mad ugliness with J. A. Rogers on jazz:

The true spirit of jazz is a joyous revolt from convention, custom, authority, boredom, even sorrow – from everything that would confine the soul of man and hinder its riding free on the air … it has been such a balm for modern ennui, and has become a safety valve for modern machine-ridden and convention-bound society. It is the revolt of the emotions against repression (ibid.: 217).

And so on.

Paul Robeson himself was one of the clearest exponents of this view. In an article in The Spectator of 15 June 1934, he spelt out this black/white, emotion/intellect, nature/civilisation opposition very directly:

The white man has made a fetish of intellect and worships the God of thought; the Negro feels rather than thinks, experiences emotions directly rather than interprets them by roundabout and devious abstractions, and apprehends the outside world by means of intuitive perceptions instead of through a carefully built up system of logical analysis.

(Robeson 1978: 65)

One difference between some of the black discourses on blackness (and Robeson) and some of the white is the kind of relationship assumed between the spontaneous/natural/simple/emotional quality of blackness and the civilised/rational/technological/arid quality of whiteness. Many of the contributors to The New Negro see the relationship very much in terms of black emotion as a resource to be transformed into a fully mature culture and to revitalise aesthetic expression. They often stress its limitations as it stands, but see it rather as a shot in the arm for pallid white art. Often too they have a vision of a synthesis of black feeling and white intellect, black sensuousness and white technology, and this emerges very clearly in their treatment of Africa. Two of Robeson's films, Song of Freedom (1936) and Jericho (1937), are explicit statements of this theme, both concerned with a Western black man who returns to (Song of Freedom) or lands up in (Jericho) Africa, and sees his mission as the bringing of the benefits of Western medicine, technology and education to the vibrant emotional life of the country. The films thus explore (more complexly than I've just indicated) one of what Alain Locke (1968: 14–15) calls the

constructive channels opening out into which the balked social feelings of the American Negro can flow freely … [namely] acting as the advance-guard of the African peoples in their contact with Twentieth Century civilisation … Garveyism may be a transient, if spectacular, phenomenon, but the possible role of the American Negro in the future development of Africa is one of the most constructive and universally helpful missions that any modern people can lay claim to.

The white positive valuation of blackness does not have these tendencies towards racial synthesis, but on the contrary often seems to want to ensure that blacks keep their blackness unsullied. One can see this in much of the white critical response to Robeson's Othello.

Robeson played Othello three times – in London in 1930, in New York and on tour from 1943–5, and at Stratford-on-Avon in 1959. It was well received, though English critics were protectively quick to say of the 1930 production that Robeson had not really mastered the verse. Still, James Agate, for instance, praised, without stating the racial connection, those qualities that reproduced an inflection of the notion of blackness we are discussing – by the end of the play, ‘Othello ceased to be human and became a gibbering primeval man’ (Sunday Times, 25.5. 30; quoted in Schlosser 1970: 133). By the time of the New York production Robeson had ‘mastered the verse’; he was also playing the role in terms of Othello as a man of dignity whose racial honour is betrayed (rather than purely in terms of sexual jealousy). The dignity and verse-speaking were noted, but the critics were now regretting that, for instance, his ‘savagery is not believable, the core of violence is lacking’ (Rosamund Gilder, Theatre Arts, 27 December 1943: 702; quoted in Rosenberg 1961: 153). Similar comment greeted the Stratford performance, Alan Brien explicitly linking Robeson's Othello to the safe, gentle image of the black man and regretting the absence of the primitivistic element:

Mr Robeson … might be the son of Uncle Tom being taught a cruel lesson by Simon Legree … I pitied him, but in my pity I never felt any of the wild, guilty, apocalyptic exultation at the vision of Chaos come again.

(The Spectator, 10.4. 59).

As Marvin Rosenberg (1961: 202) shows in his study of the history of Othello productions, despite the many disagreements about the interpretation of the title role, the idea of its involving ‘a passion so demented, so entire that once roused it seizes and dominates the man’ has been held as essential since the play was first produced. This can be understood in purely individual terms – Othello is someone like that – or universal ones – everyone is like that – but it can also be understood racially. The play allows this rather forcefully – Iago is able to draw upon a fund of racist ideas about blacks, and black sexuality, to further his own resentment against Othello:

(to Brabanto, Desdemona's father)

Even now, now, very now, an old black ram

Is tupping your white ewe. Arise, arise …

Or else the devil will make a grandsire of you.

(Act One, Scene 1)

and he articulates the claims of (white?) reason against (black?) sensuality:

If the balance of our lives had not one scale of reason to poise another of sensuality, the blood and baseness of our natures would conduct us to most preposterous conclusions. But we have reason to cool our raging motions, our carnal stings, our unbitted lusts.

(Act One, Scene 3)

We have no need to take the racial equation. Certainly the character of Othello might be played as a contradiction of Iago's view, the play as a whole not endorsing this concept of blackness. This presumably was part of what Robeson was trying to do. However, as Rosenberg notes (though again without pressing the evident connection with racial notions), it has been common in the twentieth century to view Othello in terms very close to the definition of blackness we are discussing – the idea of Othello ‘as a primitive or barbarian veneered by civilisation, hence easily plunged into savage passion, has been a fairly popular critical interpretation’ (Rosenberg 1961: 191–2, my emphases). Faced with a black man, Paul Robeson, playing Othello, white critics easily expected this primitivist interpretation and when they did not get it were disappointed (especially as they felt they had done so in 1930).

Robeson's Othello did make an issue out of the fact that Othello was black, or at any rate did so at the level of widely reported intention. But he wanted to emphasise the social position of Othello, a black man in a white society, someone living outside their culture. The critical reaction, however, suggests a desire to see the racial dimension in terms of essential racial differences, the blackness of emotionality, unreason and sensuality.

Black and white discourses on blackness seem to be valuing the same things – spontaneity, emotion, naturalness – yet giving them a different implication. Black discourses see them as contributions to the development of society, white as enviable qualities that only blacks have. This same difference runs through the two major traditions of representing blacks that Robeson fits into – blackness as folk, blackness as atavism.

BLACK AS FOLK

We black men seem the sole oasis of simple faith and reverence in a dusty desert of dollars and smartness.

W. E. B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk

In his biography of Jerome Kern (the composer of Show Boat), Gerald Bordman (1980: 400) recounts a visit made by Kern to a Phil Silvers cabaret in 1944, in which there was a skit on Kern teaching Paul Robeson ‘Old Man River’:

Much of the fun derived from contrasting the grammar and rhetoric of the unlettered black man who is supposed to sing the song in the show with the college-educated Robeson's meticulous English. Robeson, for example, demands to know what ‘taters’ are and when he is told then attempts to sing the line in his impeccable Rutgers grammar. But even Robeson must admit that ‘He doesn't plant potatoes …’ fails to work.

Part of the gag is anti-Robeson, his overeducatedness and effrontery in changing the words of the song (discussed below); but it does have a more progressive implication too.

No one, presumably, has ever thought ‘Old Man River’ was a genuine folk song, but it has often been credited with having a folk feel and certainly as sung by Robeson it was widely felt to express a Negro essence. Virginia Hamilton, in her 1974 biography for children, writes of the London Show Boat audience listening to ‘Old Man River’ and gazing ‘openmouthed at this man who had somehow clasped the history of his people to his soul’(51). Yet what the Phil Silvers skit emphasises is the artificiality of this. Robeson as Joe was not a case of natural emanation but something that had to be worked up, learnt, produced as a particular image (and then, later, resisted as an image). The very idea of folk culture or consciousness is a construct, though one that gets its force and appeal from appearing not to be, from notions of naturalness and spontaneity.

In a discussion of black folk literature in The New Negro (Locke 1968: 242), Arthur HuffFausset conveniently summarises the components of this concept of folkness. Folk is characterised by

1 Lack of the self-conscious element found in ordinary literature.

2 Nearness to nature.

3 Universal appeal.

This can be quickly disputed – self-consciousness is a defining feature of particular kinds of literature only and folk stories are certainly conscious of their own conventions; there is no evidence that literature from one folk culture appeals to all people everywhere (or even, as may be implied, in all other folk cultures); and the notion of ‘nearness to nature’, as anthropologists like Mary Douglas have shown, involves us in not seeing how highly wrought is the sense tribal societies make of the natural world. However, what is important here is that these kinds of ideas about folk culture were believed and inform the development of black images and of Robeson in particular.

This is not to deny that there might be such a thing as folk culture, if we define this simply as those cultures produced in rural, peasant societies – but there is no a priori similarity between those societies and their cultures, and certainly not of the kind evoked by Fausset. That kind of image of folk culture derives most immediately from the Romantic movement (although with a still larger history – see Raymond Williams’ The Country and the City), and, in the case of its application to black American culture, more specifically from the nationalist schools of music and literature that developed in Europe towards the end of the nineteenth century. The connection between these movements and the kind of folk work Robeson was involved in is quite precise. In the case of music, the link is Anton Dvořák, one of the major examples of a romantic nationalist composer, who used the peasant music of his country as a source and inspiration for his own music. He established, with Jeanette Thurber, the National Conservatory of Music, with the remarkable policy of recruiting equal numbers of white, black and Native American students, in order to foster ‘authentic’ American music rooted in folk music traditions (see Cruse 1978: 54). One of his students was Harry T. Burleigh, whose arrangement of ‘Deep River’, published in 1916, established the spiritual as a form of art song, acceptable in the concert hall. The spirituals were the cornerstone of the Harlem Renaissance argument for black folk culture, and were the basis of Robeson's concert and recording work.

The drama connection is similarly precise. The first plays to deal with black subjects from a folk perspective were written by the white Southern playwright, Ridgley Torrence, and he explicitly modelled himself on the work of Yeats, Synge and Lady Gregory in Ireland, probably inspired by the visit of the Abbey Players to New York in 1911 (see Clum 1969). The connection was seen straightaway by one of the most enthusiastic white supporters of the Harlem Renaissance, Carl Van Vechten – of Torrence's ‘Negro play’ Granny Maumee he wrote ‘the whole thing is as real, as fresh, as the beginning of the Irish theatre movement must have been in Dublin’ (New York Press 31.3. 14: 12; quoted by Clum 1969: 99). Paul Robeson's first stage appearance was in a production of Torrence's Simon the Cyrenian (at the Harlem YMCA in 1920), and it was his performance in this that impressed Eugene O'Neill, himself developing a folk-based drama. Robeson subsequently appeared in three of his plays, including The Emperor Jones – one of the roles that established his reputation – in the theatre and in the film version. Further developments of this kind of folk drama include Porgy by Dorothy and DuBose Heyward (described by James Weldon Johnson (1968: 211), the first major chronicler of the Harlem Renaissance, as ‘a folk play … [which] carried conviction through its sincere simplicity’), in a 1927 revival of which Robeson played Crown; and Porgy and Bess 1935, a ‘folk opera’ based on Porgy, several of whose songs Robeson recorded with considerable success.

The nationalist movements in music and literature occurred in Europe in those countries at the point of undergoing a rapid spurt of industrialisation and urbanisation, and at a time when the rural, peasant experience that is the basis of folk art was becoming increasingly untypical of the population as a whole. Yet it is just this untypical situation and experience which is labelled, by nationalist aesthetic movements, as the characterising culture of the country. Similarly, the spirituals as concert music and the plays of Torrence, O'Neill, the Heywards and others occur as a celebration of the Southern Negro situation and experience at the end of a massive migration of black people in the USA to the cities of the North, and supremely to Harlem, the urban heartland of these productions of the Southern Negro essence.

The Negro folk idea, and Robeson's relation to it, is probably best looked at through the spirituals rather than the folk dramas. Not only were the spirituals the art form that the Harlem Renaissance pinned its colours to in terms of its claims for Negro culture, they are also the most enduring feature of Robeson's career, not only in concerts but as a regular part of his stage and film appearances. (The films do not necessarily include true spirituals, but they do feature folk material or imitation folk material – and though the issue of genuineness and authenticity can be crucial in discussions of folk, at the level of popular representation the folk feel can pass muster.) There was general agreement that Robeson's approach to the singing of spirituals was ‘simple’ and ‘pure’, but the kinds of emotions and meanings that he conveyed through the spirituals were more widely interpreted.

Robeson's musical qualities seem to exemplify Albert C. Barnes’ view of the essence of the spiritual – ‘natural, naive, untutored, spontaneous’ (Locke 1968: 21). Mary White Ovington (1927: 213), a (white) member of the Niagara group and founder member of the NAACP, stressed that Robeson retained the simple essence of the spiritual because he was in touch with its roots in folk culture:

Robeson had heard these songs in his boyhood as the older generation had given them, simply, without diminuendo tailpieces or a conductor's pounding of time at each new line … Thus Robeson came to his … triumph as a singer of spirituals.

Musically there is no disputing Robeson's simplicity and purity, if we are careful about what we mean by these terms.

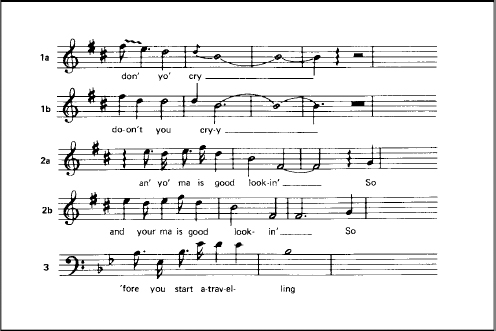

By simple is meant that he sings the melody straight through, with little adornment whether of the classical singer's trills, slides and other decorations or the jazz use of syncopation or phrasing that bends, delays, quickens or plays on the melody. By pure is meant that his voice always remains within the strict tonal system of Western harmony, not using any of the ‘dirty’ notes of black blues, gospel and soul music. You are made aware of Robeson's pure and simple approach when you listen to him singing songs that are not written to be sung like that. His recordings of ‘Summertime’ and ‘A Woman is a Sometime Thing’ from Porgy and Bess with the Carroll Gibbons Orchestra illustrate this. One does not expect the kind of intensified jazz play of Lena Horne's 1957 recording of ‘Summertime’ or Leontyne Price's syncopated coloratura treatment in her 1981 recording, but even the relatively straightforward recordings and the score itself indicate a number of syncopated and ‘impure’ elements that Robeson eschews. Where Gershwin has slides and uneven notes on ‘Don't you cry’ (e. g. 1a), Robeson sings precisely separated, even notes (e. g. 1b),3 and the syncopation required for phrases like ‘an’ yo’ ma is good-lookin’’ (e. g. 2a) becomes evenly paced notes in Robeson (e. g. 2b). These ‘purifications’ of Gershwin are even more noticeable in ‘A Woman is a Sometime Thing’, anyway a more jazz-related number. All singers that I have heard, save Robeson, bring out the rhythm of a phrase like ‘’Fore you start a-travellin’’ (e. g. 3) by a syncopated stress on ‘’Fore’ and a longer stress on ‘tra-’ and consequently shorter ones on ‘-ellin’’, details that the classically based notation system cannot render. Robeson, however, gives little stress to ‘’Fore’ and sings ‘travellin’’ as three notes of correct (as notated) length.

Similarly his only blues recording, of ‘King Joe’ (‘Joe Louis Blues’) with the Count Basie band in 1941, shows, by the concessions it makes to blues style, how little touched by these black music traditions Robeson generally is. At the end of phrases he gets that sense of falling on to a note, characteristic of blues singing, of which perhaps the most memorable, because most lyrically appropriate, example is ‘I hate to see the evenin’ sun go down’. Thus in ‘King Joe’ he sings:

They say Joe don't talk much

He talks all the time

They say Joe don't talk much

He talks all the time

He also sings the blue notes of the tune (as, of course, he has to if he is going to sing it at all). But on an exultant final phrase like

But the best is Harlem

When a Joe Louis fight is through

he is too concerned to get all the words in to allow for any hollering or rasping, or even for extending ‘fight’ briefly but tellingly beyond the strict time-value that the note accords it.

If Robeson sings without any of the conventions of jazz blues, his form of folk singing also bears little resemblance to the kind of nasal delivery that is now customary in folk and folk-inspired music. Robeson's singing is art or concert singing without the flourishes – hence pure of tone and simple of delivery. And this purity and simplicity was taken to be the hallmark of singing which caught the folk essence of the spirituals. Robeson was held to return to the true basis of the spiritual, without recourse to symphonic elaboration, as Ovington noted above, and without, as Elizabeth Sergeant (1926: 207) put it, ‘lapses into jazzed effects and the Russian harmonies that have recently crept into the Spirituals’.

If symphonic and jazz inflections were not true to the spiritual, then nor was pure and simple singing either, if by true is meant accurately reproducing how they were originally sung. The development of the spiritual as a form of concert music was a history of the purification of the spirituals of all their ‘dirtiness’, intricacy and complexity. To begin with, they were not solo songs anyway but choral, often using elaborate forms of harmony and counter-melody, and the call-and-response patterns characteristic of African music. Polyphony was achieved through the use of vocal timbres, and this subtle sound colouring was developed through the use of various kinds of instrumental accompaniment. Finally, they were rhythmically very complex, making great use of contrapuntal elements (see Roach 1973: 31–3). None of this survives into the concert hall, or record-selling, spiritual. Indeed such elements were consciously expunged both by Harry T. Burleigh (see Southern 1971a: 286–7) and by George L. White, choirmaster of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, the first choir to popularise spirituals in the USA. White aimed for ‘Finish, precision and sincerity’ (quoted by Roberts 1973: 161); in effect, purity and simplicity.

It may well be true that, had it not been for these adjustments, this black music tradition might never have become as widely popular, and marketable, as it did. But purity and simplicity are not only neutral musical terms, they are also value terms, they describe certain ethical qualities that folk cultures are held to maintain and that are supposed to be expressed in folk music. Musical purity and simplicity become purity and simplicity of heart.

The idea that the Negro folk character is itself simple and pure runs through much of The New Negro and texts inspired by it. Many of these texts are quite nuanced. Locke (1968: 200), for instance, stresses that simplicity of means does not imply simplicity of meaning:

For what general opinion regards as simple and transparent about [the spirituals] is in technical ways, though instinctive, very intricate and complex, and what is taken as whimsical and child-like is in truth, though naive, very profound.

Moreover, in the black discourse the spirituals are seen – though not invariably – as cultural products rather than an innate predisposition granted along with dark skin.

These nuances and culture-based conceptions of simplicity and purity were easily lost sight of in white discourses, probably under pressure from what remained one of the most powerful images of blackness, Uncle Tom.4 Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel (1852) fixed a particular conception of the black character in liberal white discourse, and it is one founded on notions of purity and simplicity. Her description of Uncle Tom could be a description of Paul Robeson (or one way of seeing him), not only because of the character traits but because of the physical similarity:

a large, broad-chested, powerfully-made man, of a full glossy black, and a face whose truly African features were characterised by an expression of grave and steady good sense, united with much kindliness and benevolence. There was something about his whole air, self-respecting and dignified, yet united with a humble and confiding simplicity.

(Stowe 1981: 68)

Size, dignity, simplicity – these terms recur so frequently with reference to Robeson that you will find them scattered throughout the quotations used in this chapter. There were, besides, more or less direct references to Robeson as Uncle Tom throughout his career. The New York Times wrote of him in All God's Chillun Got Wings, ‘the hero … is as admirable, honest and loyal as Uncle Tom’ (quoted in Seton 1958: 64), and the play itself ends with the defeat of Jim's plans to become a lawyer and his acceptance of playing Ella's ‘Uncle Jim’. ‘Old Man River’ was often seen in Uncle Tom-ish terms – Brooks Atkinson greeted Robeson's singing of it in the New York revival as an expression of ‘the humble patience of the Negro race’ (20.5. 32; quoted by Schlosser 1970: 142), and Robert Garland referred to Robeson's Joe as ‘one of God's children with a song in his soul’ (New York World Telegram,20.5. 32; quoted by Schlosser, ibid.). Similar interpretations met his film performance, although for the black press this was a negative quality:

if indeed he has ever died in the theater or on the screen, Uncle Tom has a true exponent in Paul Robeson.

(California News, 8.3. 36; quoted by Schlosser, ibid.: 252)

I have already quoted Alan Brien's reference to Robeson's 1959 Othello as Uncle Tom.

Stowe, like other white people later – compare Mabel Dodge's words quoted above – developed an image of blackness as a repository of all the qualities that she considered lacking in the dominant society of her day. As George M. Fredrickson (1972) shows in his The Black Image in the White Mind, Uncle Tom's Cabin is not only a protest against slavery but a wider critique of contemporary society as materialistic, aggressive and over rational. Stowe sets many of her black characters, and also many of her female ones, against this image of society. Her argument – and hers is only the most imaginatively powerful expression of widespread liberal thought – was that, since blacks were so pure and simple, it was unchristian to treat them badly and that, in their purity and simplicity, they held a lesson for white society. But it was possible for her listeners not to hear the second part of the argument and to draw a different conclusion from her compelling image of the Negro character. Her imagery is based on earlier pro-slavery literature that had depicted the Negro as docile and humble, as long as he or she remained a slave; that argued that blacks had a predisposition to bondage, and that it was against their natures to be free; that blacks were happiest kept in their lowly pure and simple state. Moreover, in validating blacks’ lack of aggression, Stowe offered no model of black advancement by any means, violent or otherwise. If blacks are so wonderful oppressed, what need have they of liberation? Indeed, are they in that case really oppressed at all?

This is the crux of the Uncle Tom image. By validating Negro qualities it keeps the Negro in her/his place, and it permits the dimension of oppression, of slavery and racism, to be written out of the white perception of the black experience. The simple and pure distillation of the Negro essence in the development of the spirituals and Robeson's singing of them purges blackness of the scars of slavery, of the recognition of racism. At most these elements are marginalised or rendered invisible. None of Robeson's films confronts slavery or racism directly, but neither was it in the meaning of the spirituals and Robeson's singing of them. Or rather – and this is the point – it was possible not to hear it there, not to discern it in his much vaunted ‘expressiveness’.

To say that Robeson sang simple and pure does not mean that he sang without expression. He had a deep, sonorous voice, but was able to soften it to convey a range of gentle, tender, sweet, melancholy qualities. Equally he used not so much loudness as intensification of his voice to convey strong, deeply felt emotion. In his rendition of ‘Deep River’ in The Proud Valley (1939), the close-up allows us to see the effort involved in the singing, the deep breaths, the moistening of the lips between phrases, which signal the intensity of the feeling that is being produced. Softening and intensification of a rich, deep voice – these means were constantly found profoundly, movingly expressive; but expressive of what?

The answer, or rather answers, to that are suggested if we consider what the spirituals were held to express. This is a subject of controversy. More clearly here than in the general discussions of the negro folk character, one can see the different way white and black discourses hear and feel the same material.

One might say that the ultimate white person's spiritual is ‘Old Man River’ though of course it is not a spiritual at all. But it expresses the basic emotional tone that whites heard in spirituals and in Robeson's voice – sorrowing, melancholy, suffering. Moreover, the way it reiterates the river imagery allows the cause of this suffering to be laid at the door of the river's indifference and to be transmitted into the eternal lot of mankind, as borne, conveniently for the white half of the community, by blacks ‘Old Man River’ does contain references to slavery and oppression, even before Robeson started changing the lyrics in an effort of resistance against the song's more generally heard message of resignation. There is reference to the fact that ‘darkies all work while de white man play’ and ‘you don't dast make de white boss frown’, but this is swallowed up in the generalised reference to ‘you and me’ who ‘sweat and strain’ in the face of the endlessly rolling river.

It is this mood of sorrow and resignation that whites heard, after all without difficulty, in Robeson favourites like ‘Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen’ and ‘Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child’. River imagery, apparently echoing the melancholy of ‘Old Man River’, recurs again and again in his song repertoire – ‘Deep River’, ‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot’ (‘I looked over Jordan …’), ‘River Stay Way from my Door’, ‘Sleepy River’ written for Song of Freedom, ‘The Volga Boat Song’, ‘Four Rivers’ (see Musser 2002), and so on.

River imagery is very common in black American folk music – Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein were right to put it into the mouth of the chief Negro character in Show Boat, but wrong to make it mean the eternal vale of life's tears. Within the context of slavery, river imagery has a dense set of meanings, all to do with deliverance from the oppression of slavery. It could refer to hope in the hereafter, crossing over the river of death into heaven, but it could also refer to rivers of escape, to the North and Canada, or else to the Atlantic Ocean, crossing that river not only to escape but to return to the homeland, Africa. The familiar spirituals (though not, of course, ‘Old Man River’ or ‘Sleepy River’, that were composed in line with the melancholy-resignation image of the spirituals) take on a very different significance when heard this way. ‘Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child’ is not just an ever-sorrowing lament but a reference to the fact of slavery ‘a long ways from home’ (i. e. Africa), and the second verse, ‘Sometimes I feel like I'm almost gone’, is no longer a mournful statement of weariness and pain, but a recognition of death or escape as a release from slavery. The fourth line of the refrain of ‘Deep River’, ‘I want to cross over into camp ground’, is meaningless to white ears but a reference in black tradition to the secret camp meetings where it was possible to meet slaves newly arrived from Africa and hence have contact with the homeland (see Southern 1971b: 82–7 and Walton 1972: 25–8). In this reading, the spirituals are not about some innate Negro predisposition to suffering, but about the suffering inflicted on generations of black people by slavery and, by extension, by white racism since abolition.

But slavery could not be spoken – it represented too much guilt for whites, too much shame for blacks. Thus even though in interviews Robeson often stressed that he thought he was expressing the sufferings of slavery and the slaves’ hope for release, it was easy to hear those deep, gentle, intensified cadences as expressive of a more generalised racial feeling. Slavery and racism would base the black folk image in historical reality; but if you didn't hear that element in the spirituals, see it in Robeson, the folk image became the unchanging, unchangeable fate of the black people.

ATAVISM

The idea of the black race as a repository of uncontaminated feeling informs the atavistic image as much as the folk image, and both have been acceptable to blacks and to whites. But whereas the folk image can be read as an Uncle Tom image, the atavistic image can be read through the other major male black stereotype, the Brute or Beast.

Atavism as a term need only mean the recovery of qualities and values held by one's ancestors, but it carries with it rather more vivid connotations. It implies the recovery of qualities that have been carried in the blood from generation to generation, and this may also be crossed with a certain kind of Freudianism, suggesting repressed or taboo impulses and emotions that may be recovered. It also suggests raw, violent, chaotic and ‘primitive’ emotions. It is this complex of ideas and feelings that is at issue when considering notions of atavism in relation to blackness and Robeson.

Atavism, in the black American/Robeson context, involves first the question of Africa, for it was to Africa that the unrepressed black psyche was held to return. What Africa was presumed to be like was then also what blacks were supposed to be like deep down, and the potent atavistic image of Africa acted as a guarantee of the authentic wildness within of the people who had come from there. This was held equally, though with different understandings, within black and white discourses – at one level, atavism was simply the tougher, more energetic version of the folk image. Robeson's relation to both the African and the more generalised atavistic image is quite complicated. In principle embracing Africa as a homeland, his film and stage work is implicitly a rejection of the idea of Africa; and while initially associated with the more general wildness-within idea of atavism, this is dropped quite early on in his career, too close to the brute stereotype to appease white fears or please black aspirations.

Africa

An initial problem was that of knowing what Africa was like. There is an emphasis in much of the work Robeson is associated with on being authentic. The tendency is to assume that if you have an actual African doing something, or use actual African languages or dance movements, you will capture the truly African. In the African dream section of Taboo 1922, the first professional stage play Robeson was in, there was ‘an African dance done by C. Kamba Simargo, a native’ (Johnson: 1968 192); for Basalik (1935), ‘real’ African dancers were employed (Schlosser 1970: 156). The titles for The Emperor Jones 1933 tell us that the tom-toms have been ‘anthropologically recorded’, and several of the films use ethnographic props and footage – Sanders of the River (1934, conical huts, kraals, canoes, shields, calabashes and spears, cf. Schlosser 1970: 234), Song of Freedom (1936, Devil Dancers of Sierra Leone, cf. ibid.: 256) and King Solomon's Mines 1936. Princess Gaza in Jericho 1937 is played by the real-life African princess Kouka of Sudan. Robeson was also widely known to have researched a great deal into African culture; his concerts often included brief lectures demonstrating the similarity between the structures of African folk song and that of other, both Western and Eastern, cultures (see Schlosser 1970: 332). However, this authentication of the African elements in his work is beset with problems. In practice, these are genuine notes inserted into works produced decidedly within American and British discourses on Africa. These moments of song, dance, speech and stage presence are either inflected by the containing discourses as Savage Africa or else remain opaque, folkloric, touristic. No doubt the ethnographic footage of dances in the British films records complex ritual meanings, but the films give us no idea what these are and so they remain mysterious savagery. Moreover, as is discussed later, Robeson himself is for the most part distinguished from these elements rather than identified with them; they remain ‘other’. This authentication enterprise also falls foul of being only empirically authentic – it lacks a concern with the paradigms through which one observes any empirical phenomenon. Not only are the ‘real’ African elements left undefended from their immediate theatrical or filmic context, they have already been perceived through discourses on Africa that have labelled them primitive, often with a flattering intention.

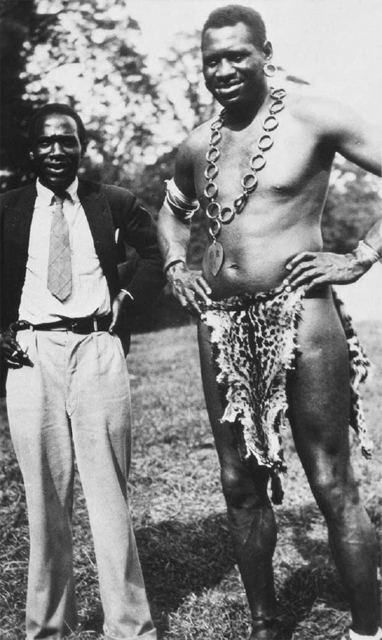

This is not just a question of white, racist views of Africa. It springs from the problem, as Marion Berghahn (1977) notes, that black American knowledge of Africa also comes largely through white sources. It has to come to terms with the image of Africa in those sources, and very often in picking out for rejection the obvious racism there is a tendency to assume that what is left over is a residue of transparent knowledge about Africa. To put the problem more directly, and with an echo of DuBois’ notion of the ‘twoness’ of the black American – when confronting Africa, the black Westerner has to cope with the fact that she or he is of the West. The problem and its sometimes bitter ironies, is illustrated in two publicity photos from Robeson films. The first, from the later film Jericho, shows Robeson with Wallace Ford and Henry Wilcoxon during the filming in 1937 (Figure 2.3). It is a classic tourist photo, friends snapped before a famous landmark. Robeson is dressed in Western clothes, and grouped between the two white men; they are even, by chance no doubt, grouped at a break in the row of palm trees behind them. They are not part of the landscape, they are visiting it.

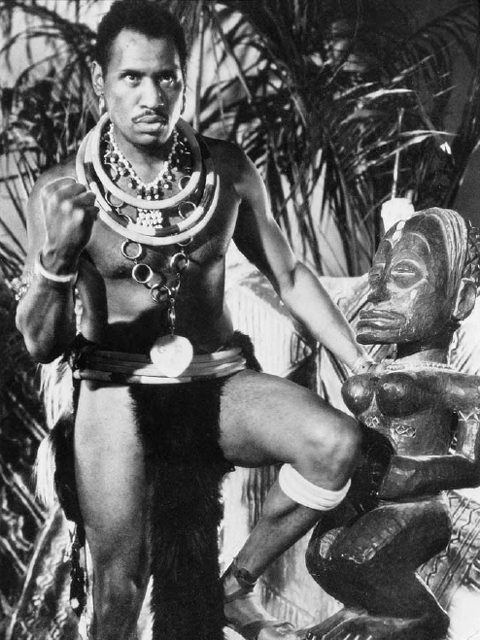

The second photo is of Robeson and Jomo Kenyatta taken during the shooting of Sanders of the River (Figure 2.4). Kenyatta, the African and future African leader who plays a chief in the film, wears white Western male attire; Robeson, the American who plays the part of a leader in all his films set in Africa, wears the standard Hollywood native (or Tarzan) get-up. As Ted Polhemus and Lynn Proctor (1978: 93) point out, clothes are major signifiers of power on the international political scene. When the West is in the ascendant, other nations dress in Western clothes; but when the relations of power shift, the leaders of non-Western nations can wear their national clothes. In the Robeson-Kenyatta photo, the politician (as he was then learning to be) who would have real power in Africa implicitly acknowledges Western cultural power in his dress; while the actor who enacts an idea of power in Africa both explicitly rejects the West in his dress and yet in fact asserts Western notions, since the dress owes far more to Western ideas about African dress than African ideas of it. It is hard to think of a more graphic example of how much a black American star is inevitably caught in Western discourses of blackness, especially when seeking blackness in African culture rather than in black American culture itself.

Figure 2.3 Wallace Ford, Robeson and Henry Wilcoxon during a break in filming Jericho 1937 (Paul Robeson Jr)

Something of this problem is confronted in Song of Freedom.5 Here, unconsciously perhaps, is an engagement with the problem for black Americans of coming to terms with Africa. When Robeson/John Zinga arrives on Casanga (the island whose rightful monarch he is, being descended from the despotic queen Zinga who had reigned a couple of centuries earlier), he is rejected by the inhabitants because of his white man's clothes. ‘Everything's so different from what I expected – it's all so primitive’, John says. He further alienates himself by breaking up a witch doctor's dance, since he believes his white man's medicine will do more good for a sick person than superstitious African dancing. He has to learn to show respect for the customs of Casanga, and it is only when he reveals that he knows the ceremonial song that ‘no white man has ever heard’ that he is finally accepted as the true king of the island.

Figure 2.4 Jomo Kenyatta and Robeson on location for Sanders of the River 1935 (Paul Robeson Jr)

The film tries to bring into line a progressive black approach to Africa and an atavistic image of Africa. John's ideas about medicine are part of the conception in black discourses of a synthesis between black spirituality and white technology; but there is no image of black African spirituality in the film, only mumbo jumbo. The positive images of African spirituality in the literary work of Hurston, McKay and others created no equivalents in popular culture; John/Robeson's spoken ideas of black and white synthesis founders on the lack of any visualisation of what the positive black contribution to that synthesis would be. The same kind of contradiction dogs, though less damagingly, the climax of the film, with John's remembering the words of the ‘Song of Freedom’. The fact that it is a song of freedom links it to a central fact of black experience, a point to which I'll return; and its narrative function is to bring order and stability to Casanga (under the rightful hereditary leader to the throne, which John is), not primeval chaos. However, the fact that John has carried a snatch of the song in his head throughout the film and that it all comes back to him at the climax suggests the (atavistic) idea of a race memory, and this is realised musically through a ‘jungle’ beat and words that suggest a release from the savagery of thunder, wild bird and lion, climaxing with the Western John Zinga/Paul Robeson singing

From the shadow of darkness

I lead my people to freedom.

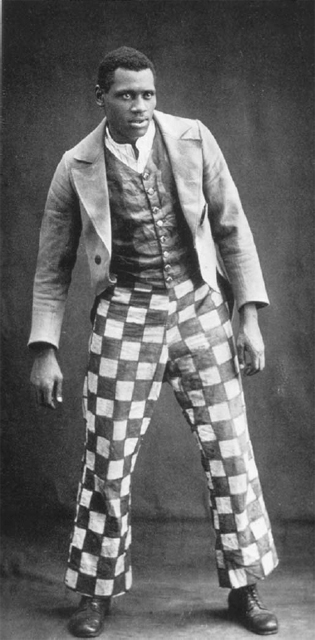

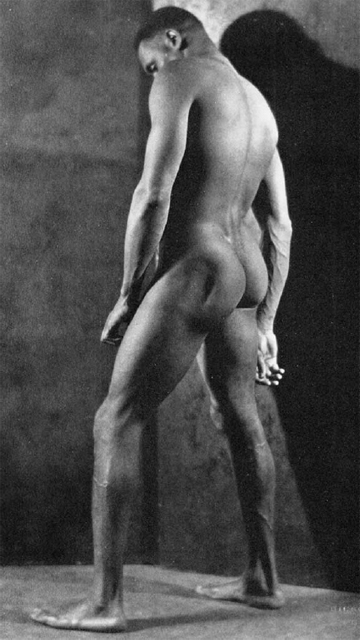

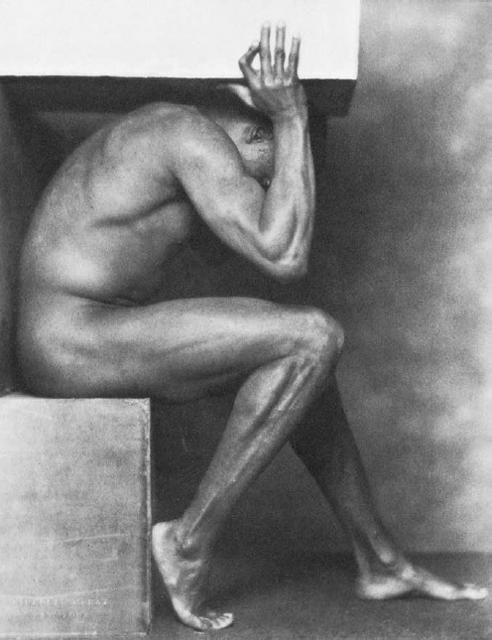

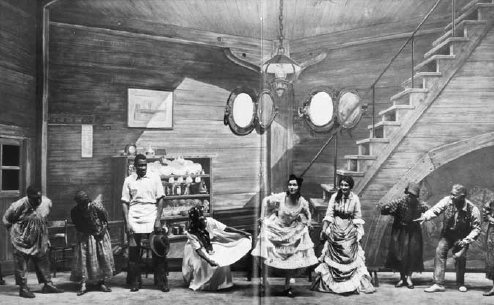

Song of Freedom is in tension with the atavistic idea of Africa, which was central to two earlier stage works, Voodoo and The Emperor Jones. Unfortunately it is hard to find out a great deal about Voodoo6 but it did involve the Robeson character, a plantation worker (pre- or post-slavery?), falling asleep and in his sleep returning to Africa. Photos of the production (which look like front-of-house pictures rather than photos of the play in performance) clearly show Robeson as a handsome, genial plantation worker and then as a manic African savage (Figures 2.5, 2.6). In his dream, the plantation worker has relived his ancestry as a wild man. The idea that seems to be implicit here, that within the civilised black man there is the trace of savage ancestry, is more explicitly and definitely present in The Emperor Jones as both play and film. Brutus Jones is a Southerner who, through cunning and threat, comes to be boss man and self-styled ‘emperor’ of a Caribbean island; but when his rule becomes intolerable, the islanders rebel and chase him through the forests of the island. The image of Jones in flight takes up nearly all the play and the larger part of the film (which includes more about Jones's life in the USA), and it is the image that is fixed as the core of the play.7

Figure 2.5 Taboo 1922: Robeson as plantation worker (Paul Robeson Jr)

Figure 2.6 Taboo. Robeson as savage (Paul Robeson Jr)

The significance of this long-drawn-out flight is that in the course of it Jones reverts from being a civilised ruler to being a chaotic, superstitious primitive. He becomes primeval, aboriginal. He stumbles deeper into the forest (→ jungle → Africa → chaos); he has hallucinations of wild beasts (alligators) and of witch doctors, as well as of moments from his US past. His manner and language become more crazed and fearful. It is a classic statement of the atavistic idea in the black context – that blacks have within them, beneath a veneer of civilisation, a chaos of primeval emotions that under stress will return, the raging repressed.

This return of the primeval repressed does not recur in any of Robeson's later roles, but the image of Africa in several of his British films does evoke these same primitivist ideas. This is not done, however, through the Robeson character himself, but rather through the general construction of an image of Africa. Perhaps the most offensively sustained example of this is Sanders of the River.

Throughout the film Africa is represented as a land of at best childish incompetence and at worst dangerous, violent ferment. The message of the film is that it is only the presence of white men that brings any law and order to the continent. The most concise and vivid illustrations of this are two montage sequences, one occurring when Sanders has left the area (to go to Britain to get married) and the other on his return. The first shows Africa reverting to chaos – the drums of the ‘bad’ tribes sending messages that Sanders is dead, ‘there is no law any more’, are cut with shots of animal wildlife, which then cut to dissolving shots of war dances and warriors marching, followed by a series of dissolves of shots of vultures, ending with more shots of drumming and marching. The sequence dramatically shows the absence of the good white ruler heralding a reversion to a state of nature which, in Africa, is also a state of chaos and threatening violence. The second sequence reverses this. Shots of the plane carrying Sanders back to the area are cut with further wildlife footage, but whereas in the earlier sequence the animals are for the most part the dangerous ones (lions, crocodiles), here they are the more harmless ones (birds, wildebeest), and where earlier they were crowding together or moving in for the kill, here they are scattering. As these latter images are also aerial shots, this gives the impression of the animals of Africa scattering before the return of the white boss in his plane. This is further linked to the end of the immediately previous sequence, where the ritual war dance of the rebellious tribes ends in a charge accompanied by catcalling. This charge is executed towards the camera, down left of the frame. The movement of the aerial camera in the Sanders return montage is forward into the space being filmed, and the animals scatter to left and right away from the camera. We are thus placed in a position that is first fearful of, and then in fantasy can quell, primitive revolt.

In the two films in which he plays an African (Sanders of the River, King Solomon's Mines), Robeson is not associated with this primitivism, but is rather presented as the exceptional figure. He is the ‘good’ African with whom the whites can work. There is a difference of emphasis between the two films – in Sanders of the River Bosambo is dependent on Sanders both for his authority (Sanders sanctions his leadership which means that his rule has white power as a back-up) and directly in the plot when he and Lilonga have to be rescued by Sanders from captivity. In King Solomon's Mines there is more sense of the whites being dependent on Umbopa, who knows the desert, is able to smell the whereabouts of water and uses his massive strength to push a boulder away from the entrance to the mines where the party is trapped. Yet Umbopa is, like Bosambo, dependent on white intervention to establish his rule – it is by using white ‘magic’ (knowledge of eclipses) that Umbopa plays upon the superstitions of ‘his people’ to convince them he is their rightful leader.

Broadly then, in Robeson's African roles he is, at the level of narrative structure, set apart from African primitive violence. This is largely true too of other aspects of the way the character is constructed. His singing, a selling point of the films, is markedly different from other singing in the films, though both are supposed to be African. Robeson/Bosambo leads the just (white-backed) war against the usurping king Mofolaba with a steady marching song, with English words in the tradition of European/American battle songs, and delivered in his booming deep voice. Later in the film, when Ferguson, Sanders’ replacement, has been captured, he is surrounded by men in masks, singing in cod African, to a hectic, irregular beat, in high-pitched voices – in every particular the antithesis of the Bosambo/Robeson war song. Similarly in King Solomon's Mines Umbopa/Robeson sings English lyrics to melodies with a regular (unsyncopated, uncomplex) rhythm and Western harmonies, while ‘his people’ sing African words and music. The latter, as with much of the footage in both Sanders of the River and King Solomon's Mines, is ‘authentic’, in the sense of being recorded on location; when, during the eclipse, Umbopa/Robeson sings in African, it is almost certainly Efik, which he learnt for the part. But the placing of these ‘genuine’ African elements is significant. In the ceremonial dance performed near the mines, at which Gagool, the (wicked, in the film's terms) wise woman of the tribe, is to select those to be sacrificed, the African singing and dancing, however authentic, functions in the narrative as a threat to our identification figures, one of whom, Umbopa/Robeson, is himself African. Moreover, an isolated shot from this scene looks like any photograph of white dignitaries looking on at African tribal performance (cf. the Royal Family's obligatory look at native customs on their visits to colonies and former colonies) – the position of ‘our’ characters in the frame, the way they hold themselves and direct their attention, reproduces the relations of power and difference of colonialism, even if in the plot it is the (to all intents and purposes) white party that is under threat.

The Robeson characters are also written as docile, good, simple characters. It is sometimes argued that within that, at the level of performance, Robeson himself suggests a level of insolence or irony that undercuts this Uncle Tom/Sambo stereotype, but this is a hard argument to sustain. It is not just editing alone (as is also often claimed) that makes Bosambo appear a lovable, rather naughty child in Sanders of the River; nor in his first meeting is it just the powerful headmaster–schoolboy rhythms of the script, though these are extraordinarily evocative:

| Sanders: | You know that every six months I call on the Orkery. |

| Bosambo: | Yes, Lord, at the time of the taxes. |

| Sanders: | Yes, Bosambo, at the time of the taxes, in a month's time. |

Robeson's performance reinforces this characterisation, often quite subtly. When Sanders questions him about whether he is a Christian, he says,

I went to missionary school, I know all about Markee, Lukee, Johnee and that certain Johnee who lost his head over a ransom girl,

but Sanders cuts him short with ‘That will do.’ Robeson/Bosambo speaks the speech just quoted with great eagerness, warming to the subject as it becomes more sexual, but then looks utterly crestfallen when Sanders stops him. This is in a two-shot, not a shot/reverse shot sequence; the eagerness and crestfallenness are conveyed through acting.

In all these ways then Robeson, unlike his roles in Voodoo and The Emperor Jones, is not identified with the atavistic view of Africa as a state of inchoate, dangerous emotion. There are perhaps slight hints of it. Bosambo's thoughts run easily to sex, as seen above, and while Sanders has to leave Africa to go away to marry, a journey that is never consummated since he has to return to Africa to quell the chaos his departure occasions, Bosambo is shown surrounded by adoring women and later marries Lilonga/Nina Mae McKinney, on the strength of an extremely sexually explicit dance she performs. Africans are allowed the sexuality that whites stoically (or relievedly) have to do without. The writing of the film of King Solomon's Mines does still have something of the ambivalence of Rider Haggard's novel, where the narrator Allan Quartermaine both admires Umbopa (‘I never saw a finer native’ (1958: 42), ‘a cheerful savage … in a dignified sort of way’ (ibid.: 46) and yet is also affronted by his arrogance (‘I am not accustomed to be talked to in that way by Kaffirs’ (ibid.: 58)). Here too the contrast is with other, inferior, more African Africans – whereas Umbopa is ‘magnificent-looking … very shapely … his skin looked scarcely more than dark’ (ibid.: 42), Twala, king of the Kukuanas, is described as ‘repulsive … the lips were as thick as a Negro's, the nose was flat … cruel and sensual to a degree’ (ibid.: 115). But hints of sexuality, traces of arrogance are but hints and traces – if anything, it would seem that such violent, difficult qualities have been eliminated, because they are threatening elements. What remains is Robeson's passive physical presence, something I'll come back to later.

Wildness within

Atavism as a reversion to Africa is then only a feature of a couple of Robeson's stage roles, and of the image of Africa in his films but not of his role in those films. The more generalised idea of atavism as wildness within is implicit in some of the other roles where the connection with Africa is not explicitly made. As an image, it is very close to the alternative black male stereotype to Uncle Tom and Sambo, namely the brute or beast.

This informs Robeson's roles not only in Voodoo and The Emperor Jones, but in Black Boy 1926, Crown in Porgy 1928 and in The Hairy Ape 1931. Even when this was not clear in the role, there was often a play on its sexual dimensions. Hints of black–white rape cling to the characters – in Basalik 1935 Robeson played an African chief who abducts (but does not in fact rape) the wife of a corrupt white governor; in Stevedore 1935, he played Lonnie Thompson, who is wrongly accused of raping a white woman at the start of the play. Equally, Othello could be read in this light – Robeson could not take the 1930 London production to Broadway because it was felt improper for an actual black man to play Othello to an actual white actress. When All God's Chillum Got Wings had been produced in New York in 1924 an enormous amount of publicity had surrounded its depiction of a black-white marriage even before its first performance. Although not the first play to deal with this topic, a perennial theme in American literature, a forceful Robeson/O'Neill/Provincetown Players treatment was anticipated as dangerous and subversive. Even when films Robeson appeared in were not in the brute mould, the advertising for them might hint that they were – Sanders of the River was sold with the following come-on: ‘A million mad savages fighting for one beautiful woman! Until three white comrades ALONE pitched into the fray and quelled the bloody revolt’ (quoted by Cripps 1977: 316).

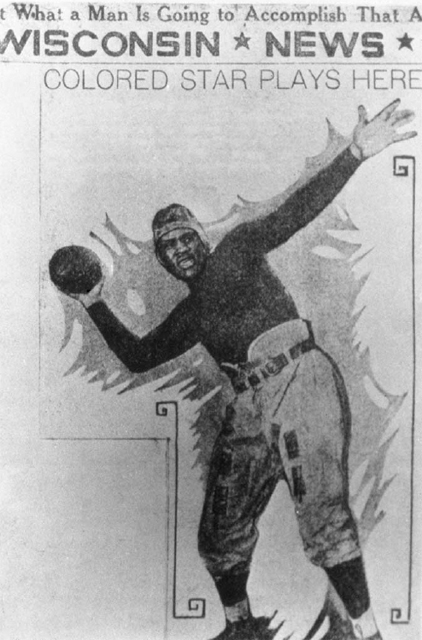

The brute image not only has a sexual dimension. As a football player, though praised largely in terms of skill and intelligence, his playing was also described as ‘vicious’ – ‘no less than three Fordham men were sent into the game at different times to take the place of those who had been battered and bruised by Robeson’ (New York Times 28.10. 17; quoted by Henderson 1939: 100). Writings about him on the field are a litany of references to his size – ‘the giant Negro’, ‘the big Rutgers Negro’ (ibid.), ‘a dark cloud … Robeson, the giant Negro’ (New York Tribune 28.10. 17, Charles A. Taylor; quoted by Hamilton 1974: 29), ‘a veritable Othello of battle … a grim, silent and compelling figure’ (quoted without reference by Ovington 1927: 207); and publicity for his appearances suggests a force and dynamism that could have been threatening (Figure 2.7).

The brute stereotype not only threatened whites, it also offended blacks. The fact that it was abandoned, along with one of its justifications, atavism, early on in Robeson's career, is a result of common cause between the two ethnic discourses. But there is a further suppressed element – slavery, again. Just as the spirituals were emptied of their slavery meanings and transformed into songs of universal suffering, so one of the possible articulations of atavism was also lost. The primary meaning of atavism was back-to-the-aboriginal-jungle, but it was possible to return to another violent race memory, that of the experience of slavery. The play of The Emperor Jones does just this. Jones's flight into the forest is systematically organised as a flight through Afro-American history – after hallucinating a general, Expressionistic vision of ‘little formless fears’ (‘if they have any describable form at all it is that of a grubworm about the size of a creeping child’, Scene Two), in the following scenes Jones sees, in this order, a Pullman porter playing dice, a black chain gang with a white guard, a group of white slave buyers ‘dressed in Southern costumes of the period of the fifties of the last century’ (Scene Five), two rows of Negro slaves huddled together in a slave ship, a Congo witch doctor.

Each of these visions is emblematic of black American history – Pullman porters were an all black trade and probably the most familiar black figures in American public life, as well as a respectable avenue of employment for black men; the chain gang was not an exclusively black experience but, then as now, blacks were disproportionately represented in penal institutions, as all oppressed peoples are; the slave trade and, finally, or rather as point of origin, Africa need no further gloss as aspects of black history. O'Neill’s use of the witch doctor clearly brings his image of Africa in line with that discussed above, and the idea of this Africanness being in all black people still is brought out in the last scene. Throughout Jones's flight tom-toms have been beaten, becoming gradually louder and faster; in the final scene, with Jones now dead, Smithers, a white trader who was in league with Jones as ruler of the island, says to the islanders who have been pursuing Jones,

I tole yer yer'd lose'im, didn't I? – wastin’ the'ole bloomin’ night beatin’ yer bloody drum and castin’ yer silly spells!

The dramatic irony is not only that we know that Jones is dead, but that his terror has been shown on stage as induced by or at least whipped up by the relentless tom-toms and his death comes as he fires his gun wildly at his final hallucination, the witch doctor. Smithers is doubly wrong – Jones is dead, and it was the drums and spells that got him. The conclusion of the play is then African atavism, but the structure of the rest of the play emphasises Jones's terror at the real, historical experience of the black man in America.

Figure 2.7 Robeson the football player, announced for Wisconsin College football game (Columbia University)

In the film, the sequence of visions is altered. Most significantly, there is no reference to slavery at all. The progression of visions seen in flight are – Jeff, a Pullman porter whom Jones worked with, playing dice; the chain gang; a Southern black church service; the witch doctor and an alligator. One of the effects of these changes is to individualise Jones's flight into his (race) memory, partly because the first three visions use shots from earlier in the film and thus retrace Jones's career before arriving on the island. Moreover, because the film has given us more of the narrative before Jones's arrival on the island, we know that it is a brawl arising out of a dice game that led to his conviction – the chain gang becomes less emblematic of a condition of oppression, and more a moment in a particular person's biography.

This individualisation goes hand-in-hand with a fundamental alteration of the facts and meaning of black history. Whereas the play gives us

low-life black employment → the ordeal of the black chain gang → the terrors of slavery → the fears of mumbo-jumbo,

the film gives us

low-life black employment → the ordeal of the chain gang → superstitious black Christianity → superstitious mumbo-jumbo.