It was just when Darwin’s book on evolution was published that America entered the dinosaur race. Fossils were already well known in the U.S.; apart from the ‘Ohio Animal’, innumerable invertebrates had been regularly collected by enthusiasts. A detailed account of animal fossils had been published in the American Journal of Science and Arts as early as 1820.1

The first dinosaur fossils to be found by geologists in North America were discovered in 1854 by Ferdinand Vandiveer Hayden, a surgeon turned geologist, while he was exploring the Missouri River near its confluence with the Judith River. His team found a few teeth that could not be identified, so they were taken to Joseph Leidy, a knowledgeable geologist who was also Professor of Anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania and a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. In 1856 Leidy published a paper that launched North American palæontology, and at the time he was the leading authority on the subject outside of Europe.2

The teeth Hayden had found eventually turned out to represent the remains of three dinosaur genera that were named Trachodon, Troodon and Deinodon. Hayden published his findings two years later, in which he briefly reported discovering teeth that Leidy had found to be from ‘two or three genera of large Saurians allied to the Iguanodon, Megalosaurus, etc’. It was becoming apparent that dinosaurs were not only to be found in the Old World; they were also relics of prehistoric America. This was a startling revelation to science. Hayden went on to lead the first major exploration of Yellowstone in 1871, and it was his report that led to the establishment of Yellowstone National Park.3

The discovery of the first near-complete dinosaur skeleton in the U.S. would revolutionize palæontology and it was announced by a keen amateur naturalist, William Parker Foulke. He was born in Philadelphia in 1816 and came from a Welsh family of Quakers who had emigrated to America in 1698. Foulke was a successful lawyer and became a prominent campaigner for civil rights. He opposed slavery, fought for prison reform, published political pamphlets, and was a prominent philanthropist. He was also an enthusiast for geology and became a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences. In 1858, just as the papers by Wallace and Darwin on evolution were being read at the Linnean Society of London and two years after Leidy had confirmed the discovery of dinosaur teeth, Foulke was staying in Haddonfield, New Jersey, and was discussing the lie of the land with John Hopkins, who farmed nearby. Hopkins was in the habit of excavating marl from a tributary of the nearby Cooper River for use as a lime-rich soil dressing. He mentioned to Foulke that, some 20 years before, workmen had dug out some huge black bones. He still had a few at his home. Foulke inquired where they came from, but the farmer tersely explained that the purpose of the work was to acquire lime for the farm, not to provide bones for a philosopher. He had thought no more about them. Foulke asked him if the digging could be resumed, to see if further bones could be found, but when they walked across to see the old digging site it had become overgrown with vegetation and much of the marl outcrop had been eroded. One of the workmen was asked to come to look at the site, but he couldn’t identify where the bones had been found and for a day or two they excavated in the wrong place. Then the worker had a brainwave – changing position, they dug down about 10 feet (3 metres) and suddenly came across a large bone. It was heavily impregnated with iron and was as black as coal. Careful excavation soon revealed the left side of a large skeleton, including 28 vertebræ, much of the pelvis and almost all the four limbs. As is the curious case with many herbivorous dinosaur fossils, there was no sign of a skull. The bones were in fragments, each of which was carefully cleaned, measured and drawn, before they were packed in straw and transported by horse and cart to Foulke’s premises less than a mile away. The skeleton proved to be that of a new type of dinosaur, which was named Hadrosaurus from the Greek ἁδρός (hadros, large) and σαῦρος (sauros, lizard). Analysis of the anatomy showed that, like Iguanodon, it seemed to stand erect and walked on its hindlegs.

Joseph Leidy, who had now become known as the nation’s leading palæontologist, was informed of the discovery by Foulke. As Leidy arrived on site he went with Foulke to the excavation and the digging continued, though nothing else was found. It was Leidy who decided to name the dinosaur Hadrosaurus foulkii to commemorate its discoverer. The skeleton was officially donated to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia in December 1858 and 10 years later was put on public display after being meticulously reassembled and mounted by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, the man who had designed the concrete dinosaurs for the Crystal Palace. Hawkins opted not to exhibit the original bones, but to prepare plaster casts that were then stained to look like the real thing. In this way, the fossil remained available for scientific study and there could always be more casts made in future. Not only was this America’s first entire dinosaur but it was the first time that any dinosaur skeleton had ever been seen in public anywhere in the world. It was a sensation. Palæontologists, anatomists, zoologists and enthusiasts travelled from far and wide to see the huge display. As the public flocked in to view the spectacular skeleton, the museum staff where soon overwhelmed. So were the exhibits. The thousands of visitors threw up so much dust that other treasures on display were threatened, and the Academy responded at first by limiting the numbers who could attend at any one time. Then they reduced the number of days each week when the exhibit was open; and finally, they began to charge admission to see the skeleton. The museum had been recording some 30,000 people each year, but that number more than doubled when the hadrosaur was put on display, attracting more than 66,000 visitors. The following year, the total topped 100,000 and the administrators launched a public appeal for funding, so that they could obtain premises large enough to accommodate everyone who wanted to come. Nothing like it had ever been experienced before.

William Foulke’s discovery of this Hadrosaurus skeleton in 1858 launched the search for dinosaurs in the United States. When the fossil was reconstructed 10 years later, it became the first dinosaur skeleton to be put on public display.

The money they collected was enough to construct a building that was twice the size, and this is the museum that still stands today at 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway. It retains much of the original architectural detail, including the galleries with their fin de siècle balustrades and the fine brick and stone façade. This is a museum that has blended modernity with tradition, unlike some others (London’s Natural History Museum being a case in point) where the dinosaur gallery has become a dimly lit children’s theme park. The Philadelphia dinosaur became world-renowned, and it remained the only fossil dinosaur on public exhibition until 1871, when a duplicate plaster copy was erected in Central Park, New York City, as a public attraction. However, the organizers had not reckoned with William Magear Tweed, an influential New York politician. Tweed was a corrupt property developer. Before he was 30, he had been elected to the House of Representatives and, although he never qualified in law, he managed to have himself certified as an attorney and set about extracting protection money from everyone he could. He was appointed to the New York Senate and was repeatedly arrested and freed, sometimes escaping from custody, and was sustained by the support of an adoring public. Tweed became known as ‘Boss’ and was deeply dishonest – he seemed to have a hand in every commercial deal in the city and soon became the third-largest landowner in New York City. Although his proclaimed wealth was largely an invention, he had himself appointed to the board of a railroad company, a major bank, a luxury hotel and a printing company; little commercial development took place in the city in which his corruption did not play a part (some readers may recognize a pattern here that makes America in 2018 seem tame by comparison). ‘Boss’ Tweed took a poor view of the new dinosaur display because he was unable to persuade the proprietors to pay protection money, so he secretly ordered the destruction of the plaster skeleton. No sooner had installation work finished than the entire skeleton was smashed to pieces and thrown into the nearby lake by his henchmen. Thus, the second dinosaur skeleton to go on display anywhere in the world fell victim to big-city corruption. Six years later, another of the casts was shipped to Scotland for display in the National Museum in Edinburgh. Fortunately, it was left unscathed and remains there to this day – the first dinosaur skeleton ever put on public display outside of the United States.4

A cast of the dinosaur skeleton from Haddonfield stood at the heart of the centennial exhibition of scientific and industrial wonders held in 1876 in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, where it shared the stage with the world’s largest steam engine and the torch that had been manufactured in readiness for installation on the Statue of Liberty. Once again, it was a sensation. Two years later, another of the casts was purchased by the Smithsonian Institution, which displayed the world-famous skeleton outside its headquarters. Another cast was bought by Princeton University and displayed in its Nassau Hall. Hadrosaurus foulkii remained the only dinosaur put on public exhibition anywhere in the world until 1883, when a Belgian Iguanodon skeleton went on display in Brussels. This was to correct a mistake Mantell had made when the first fossils were excavated – the horn he had assumed went on the snout was actually situated on the wrist, somewhat like a spiked thumb. Artists using the standard drawings as a reference for their own impressions of dinosaurs took longer to adapt; as we shall see, there was still a horn appearing on the snout of an iguanodon as late as the 1960s.

A problem soon emerged. These skeletons were all installed in an imposing upright position, with the tail resting on the ground, as a standard, terrestrial creature. But over the following decades, as palæontologists considered their findings, it was realized that the upright position was impossible – although innumerable footprints of dinosaurs like this were being discovered, there was never any sign of an impression left by the tail. Clearly, the tail of a dinosaur never touched the ground. And so, since the 1990s, dinosaur skeletons have been reconfigured with the tails held aloft. There are still some in the former, upright stance (there is one example in the State Museum in Trenton, New Jersey, and another in the Sedgwick Museum of Cambridge University), but the fossil evidence has proved that this upright stance is impossible. The hadrosaur that Foulkes discovered remains the only one anybody has found. Even though other duck-billed dinosaurs (collectively known as hadrosaurs) have since been found, there are no other specimens of the same strange species that he discovered. Furthermore, nobody knows quite what it looked like, for the skull was never located (the skeleton casts on display in museums use a manufactured skull shaped rather like that of an Iguanodon). The team at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia had made history by displaying this unique discovery. Just as the concrete sculptures of dinosaurs at the Crystal Palace had caught international attention, so had their exhibit of the first skeleton ever put on display.

This was an exciting project, and one of the team, a young zoologist who had been a child prodigy, was destined to become their curator. He was 18 years old when the skeleton arrived at the Academy, and its majesty transfixed him. This teenager was Edward Drinker Cope, and he became one of the greatest dinosaur hunters of all time. Edward was the son of Alfred and Hanna Cope, a wealthy Quaker family who ran a shipping company and had emigrated from Germany. They were resident near Philadelphia when the young Cope was born on July 28, 1840. His mother died when he was 3 years old, and Rebecca Biddle became his stepmother. They looked to the future, and Edward was taught to read and write from an early age. The family made extensive visits to parks, zoological collections and museums, for this was how a youngster was prepared for a full and satisfying life in those days. Some of Edward’s childhood notebooks survive and they show a wide-ranging interest in natural history. He was also a capable artist. At the age of 12, he was sent to boarding school at West Chester, Pennsylvania, where he studied algebra and astronomy, chemistry and physiology, scripture, grammar and Latin. Looking back at those days, we can see that earlier generations had a tradition of learning instilled at an early age – yet Edward Cope would not study subjects he disliked. Penmanship was a lesson he found difficult, and indeed his handwriting throughout his adult life was often illegible. By 1855 he was back at home and became increasingly preoccupied by natural history. He had often been taken to the Academy of Natural Sciences, and by 1858 he was working there as a part-time assistant, cataloguing and classifying specimens in the collections, when Foulkes’ dinosaur skeleton arrived. This sowed a seed that would germinate in Cope’s later years. He was captivated by the prospect of investigating magnificent monsters from long-lost worlds.

Later that year, far younger than you would expect a scientist to start publishing, Cope’s first paper appeared. It was on salamanders. Meanwhile, his father was not convinced that a life in the museum world was appropriate, and he believed that agriculture would be more suitable, so he purchased a farm for the young Cope. With considerable enterprise, Edward decided to rent out the property to a tenant farmer and he used the regular income to support him in his private interests. In 1860 he enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania, but he found their approach too pedestrian so he did not stay to graduate. (I have to admit that I had a similar experience at Cardiff University; settling down to study a syllabus with which I was already familiar did not appeal to me either, when there was a great wide world awaiting discovery.) Cope always kept the admission slip for the academic year 1861–1862, and – since these forms were always collected on the first day of the academic year – we can assume that he left university late in 1861. One of his teachers of comparative anatomy was Joseph Leidy, and it was he who encouraged the young Cope to join the staff of the Academy. Because of his position in the Academy of Natural Sciences, Cope was able to join the American Philosophical Society, and it was this august body that provided him with an outlet for many of his pioneering papers on palæontology.

Edward Drinker Cope (left), born in Philadelphia in 1840, followed Lamarck’s theory of acquired characteristics. In a 22-year period he discovered more than 1,000 new fossil species, including 56 new dinosaurs. The co-star of the ‘bone wars’ of late nineteenth-century America was Othniel Charles Marsh (right), born in 1831 in Lockport, NY. He discovered about 500 new fossil species, including 80 dinosaurs. There was much bitter rivalry between Marsh and Cope.

Two years later, the American Civil War erupted, and, to avoid the draft, Cope quit America for Europe. He travelled to England, France, Germany, Ireland, Austria and Italy, taking full advantage of the time to visit seats of learning, museums, and some of the distinguished scientists of the day. But he was unhappy for much of the time, and became depressed. He even set fire to his voluminous diaries and papers until he was prevailed upon by friends to keep some intact – but most of his early documents were lost. Cope was cheered by a visit to Berlin in 1863, where he met a fellow enthusiast who was equally fascinated by fossils. The two frequently went out together and soon became friends. This new acquaintance was Othniel Charles Marsh, who, at 32, was 9 years his senior. They were contrasting young men: whereas Cope lacked formal education after school, Marsh held two university degrees. While the eager Cope had published some 37 scientific papers, Marsh still had only two published papers to his name. Marsh took Cope out to explore the city and its museums, and the two became confidants. As they parted they agreed to correspond, and to exchange specimens. Both seemed destined for greatness. Palæontology was blossoming, and a new world awaited them.

Back in Philadelphia as the Civil War was ending, Cope’s father arranged for him to secure a teaching post at Haverford College, a private school with which the family was associated. Cope was still unqualified, so the college awarded him an honorary degree. He married a young Quaker named Annie Pim, aiming less at a romantic liaison than a practical arrangement. He was less interested in poetic passion than in the ability to manage a household, he told his father. They were married in 1865 and next year had a daughter, Julia Biddle Cope. Edward Cope continued to publish papers on anatomy, and also wrote his first paper on palæontology – it described a small carboniferous amphibian fossil Amphibamus grandiceps from Grundy County, Illinois, which he said was ‘discovered in a bed belonging to the lower part of the coal measures … imbedded in a concretion of brown limestone.’5

Cope travelled extensively in the U.S., always searching for specimens, and – although he enjoyed teaching – he complained that he had no time for his serious studies. The work on the Hadrosaurus skeleton continued to captivate him, so he sold the farm that his father had given him and moved to Haddonfield, which is where Foulke had found the fossil. Cope now started digging in the marl beds and was soon rewarded by a spectacular find. He unearthed the remains of a new dinosaur that measured 25 feet (8 metres) in length and could have weighed about 2 tons in life. He named it Laelaps aquilunguis but later discovered that the genus Laelaps had already been assigned to a small mite, so the name was changed. Today we know it as Dryptosaurus aquilunguis. He also obtained a fossil that had been discovered in Kansas and excavated by a military surgeon, Theophilus Turner. This was a 30-foot (10-metre) plesiosaur weighing about 4 tons and named Elasmosaurus platyurus. He described it as having an elongated tail and a short neck, and, always rushing to publish, he prepared an illustration that showed his newly discovered dinosaur perched on a sandbank as plesiosaurs frolicked in the nearby water.

Cope placed the skull on the tail end of an elasmosaur in the foreground of this illustration published in American Naturalist in 1869. Once Marsh had pointed out this mistake, Cope tried to have every incorrect version destroyed.

The family lived comfortably and entertained house guests. Cope was a man of enormous energy and boundless enthusiasm. Henry Weed Fowler, a zoologist friend, said he was ‘of medium height and build, but always impressive with his great energy and activity.’ Cope was a friendly and open character, and people found him approachable and kind. If a passing youngster drifted from the street into the museum where he was at work, Cope would chat animatedly about the work he was doing. Many modern accounts portray him as an avuncular and warm individual with high moral values and integrity, though some of his associates recorded that his language was foul, he had a bad temper that erupted without warning – and he was a habitual womanizer. A one-time friend, the artist Charles R. Knight, claimed that: ‘In his heyday, no woman was safe within five miles of him.’ In an era of machismo, some colleagues even admired this in Cope. One American palæontologist, Alfred Romer, commented that: ‘His little slips from virtue were those we might make ourselves, were we bolder.’ If Cope was anything, he was bold.6

Because of his Quaker upbringing, Cope never challenged his family in their belief in the literal truth of the Bible. Although he maintained a gulf between his life as a palæontologist and his views as a family man, he continued to proclaim his Christian beliefs, and many of his colleagues found his religious fervour to be at odds with his work. Although he looked to the future of science, he remained a traditionalist in family matters and was strongly opposed to women’s emancipation. Suffrage, he thought, was irrelevant to a woman whose husband alone could care for her interests and he was certain that it would be pointless for a weak woman, for she would surely be better served by conforming to her husband’s beliefs. As a self-educated man, Cope disliked academic orthodoxy, so he turned his back on administrative conformity, and was annoyed when formality threatened to limit his work. He was rebellious by nature, and saw himself on a quest for truth.

When Othniel Charles Marsh returned to America he soon called in to pay his respects. Cope took him excitedly around his excavations. He showed him some protruding bones that he next planned to excavate, and proudly showed the elasmosaur skeleton neatly reassembled and laid out. Marsh considered it all. He was a self-righteous man, but had an analytical mind; suddenly, he realized that Cope had made a fundamental mistake. He had laid out all the vertebræ the wrong way round! Cope was deeply affronted and demanded that someone authoritative should examine the bones to resolve the matter, so the curator of the Academy, Joseph Leidy, was asked to decide who was right. Gravely, Leidy inspected the fossil bones neatly laid out by Cope; then without a word he picked up the skull, strolled right along the skeleton, and placed it where it belonged – at the other end. This was not a creature with a stubby neck and a graceful tail, as Cope had thought. Instead, it had an elongated neck, for it was the tail that was short. Marsh laughed aloud. He ridiculed Cope for his elementary error, and an enduring state of animosity was established between the two. Leidy was right, of course; Cope tried to recover all the copies of the publication in which he had incorrectly portrayed the dinosaur and wanted them all destroyed. The controversy came up at the next meeting of the Academy of Natural Sciences where Leidy was asked to explain. Not only did he account for the error, but he amusingly recounted Cope’s elaborate attempt at covering up his mistake. Marsh was delighted. He had become irritated by Cope’s easy way of publishing results so rapidly and became convinced that Cope lacked the necessary objectivity to report academic findings in a considered and balanced fashion. Before he left the excavation, he had taken one of Cope’s workmen to one side and bribed him to send over any startling new discoveries. Not only did this whole episode mark the end of their friendship, but it launched a bitter battle that was to last a lifetime.

Othniel Charles Marsh was born on October 29, 1831, to Caleb Marsh and Mary Gaines Peabody in Lockport, New York. His mother Mary died of cholera before his third birthday, so her brother, the philanthropist George Peabody, set aside a fund to support the family. As a youth, Marsh developed a close friendship with Colonel Ezekiel Jewett, a remarkable soldier who had travelled the world and fought in many military campaigns. Jewett has been largely forgotten (there is no page for him in Wikipedia, though there should be) and he developed a passion for palæontology. He held classes where he taught geology, and among the young men he mentored was Charles Doolittle Walcott, who was to become a distinguished Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. The young Othniel Marsh became fascinated by everything Jewett could teach him, for he enjoyed collecting specimens, and through Jewett he learned about geology and the nature of minerals – and soon became fascinated by fossils. Jewett has been described as America’s finest field palæontologist of his age, and he found an eager student in Marsh. There were exquisite brachiopod and trilobite fossils to be found near his home, and fine examples of crinoids. On his 21st birthday, Marsh inherited the legacy bequeathed to his mother by Peabody and his life changed forever. The money funded a good education and he was such a promising student that his wealthy uncle agreed to pay for him to attend Yale College. In 1860, aged 28, he finally graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree. When the American Civil War broke out the following year, Marsh did not try to dodge the draft and was keen to enlist as a soldier, but was rejected because he was so short-sighted. Instead, with his uncle’s financial support, Marsh continued postgraduate studies in mineralogy and geology at the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale, and wrote his first scientific paper. It was entitled ‘Description of the Remains of a New Enaliosaurian (Eosaurus acadianus)’ and in July 1862 he sent a copy to Sir Charles Lyell in London. Lyell was the foremost British geologist of the day and had often been at the core of controversy.

Sir Henry Thomas de la Beche was a prolific geologist and artist. This cartoon was drawn by de la Beche in 1830 and it satirizes the views of Sir Charles Lyell. It was published in Francis Buckland’s Curiosities of Natural History (1857).

In November 1862 Othniel Marsh set sail for England. He was enthralled by the Great London Exposition, an international exhibition held that year, and he wanted to study the dinosaur fossils at the British Museum. Marsh made an appointment to meet Lyell, who was impressed by the young palæontologist and his knowledge of rocks and minerals. Lyell read a paper that Marsh had written, and delivered it at a meeting of the Geological Society. He then arranged for its publication in their journal, and even proposed Marsh as a new member of the Society, an unusual distinction for someone so new to the field. Early the following year Marsh moved to Berlin to study mineralogy and chemistry, and he then travelled on to Heidelberg and Breslau. His ailing uncle visited Wiesbaden that spring, and when he told Marsh that he was making plans for the allocation of his wealth to worthy causes, Marsh suggested that he should fund a new building at Yale. George Peabody gave a donation of $150,000 (now worth about £5 million, or $6 million) and the Peabody Natural History Museum was the result. Switzerland was next on Marsh’s itinerary, and he later returned to Berlin, which is where he first encountered Cope.

These were crucial times for Marsh. New discoveries of fossil dinosaurs were being reported everywhere and – buoyed up by his time spent with Cope – he became determined to devote his life to this fashionable branch of science. In 1866, when he returned to Yale University, it was to become their Professor of Vertebrate Palæontology. This was the first such post in American history. Marsh was appointed a curator of the Peabody Natural History Museum in 1867, and the museum soon became one of the world’s leading institutes for dinosaur research. Two years later Peabody died, leaving his nephew a generous inheritance. Marsh was now able to devote himself full-time to palæontology, and built his family a large home in which he entertained luminaries including Alfred Russel Wallace, and in which he could display a vast collection of specimens. The building still exists on Prospect Hill in New Haven, Connecticut. It is now administered by the School of Forestry & Environmental Studies of Yale University.

Marsh could now relish his position as the most eminent palæontologist in the U.S. He stood tall for the time, measuring 5 feet 10 inches (1.7 metres), with a florid complexion and wide-set piercing blue eyes. He was a bulky man with a round face, and he had a reddish beard and sandy hair, the hairline riding high on his forehead. Marsh struck visitors as confident, though at first hesitant and suspicious; his manner was shrewd and, some said, cunning. He had enormous energy and unlimited enthusiasm for palæontology, and was known as a dominant character who fully exploited his position as the leading figure in his field. He wanted to be the best, and indeed, he knew that he was. The British palæontologist Sir Arthur Smith Woodward, whose father Henry Bolingbroke Woodward was one of Marsh’s closest friends, said that the family found Marsh to be jealous by nature and desperately keen to attract as much adulation as he could. Nothing pleased him more than the attention of others, and he found it difficult to cooperate with rivals, always seeing them instead as competitors to be vanquished. This attitude fuelled his enduring rivalry with Cope. It was a state of open warfare between the two that led to bitter exchanges and, curiously enough, to the greatest explosion of research into fossil dinosaurs. Had these men not been driven by the passion of animosity, it is unlikely that the astonishing rate of discovery that marked this era in American palæontology would ever have taken place.7

These days we look at the Midwest of the U.S. as a vast plain, leading up to the towering Rocky Mountains, and interspersed with genteel cities and scattered settlements. Yet, just a few decades ago, it was a very different place. Older readers may remember the start of Muffin the Mule (in England) or The Ed Sullivan Show (in America) on television. Well, they were launched some 70 years ago and if we go back just another 70 years earlier, we are in 1878 when the repercussions of the Battle of the Little Bighorn and Custer’s Last Stand were still resounding – truly, it is not such a long time ago. The great battle that resulted in Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s resounding defeat occurred on June 26, 1876, along the Little Bighorn River in Eastern Montana. The government in Washington had sent out the 7th Cavalry Regiment of the U.S. Army to engage with the Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes as the occupying European settlers sought to move west. This battle was the culmination of the resulting Great Sioux War and it was an overwhelming victory for the indigenous people. Of the 12 army companies, 5 were completely annihilated. Lieutenant Colonel George Custer died, along with 2 of his brothers, a brother-in-law and his nephew. Of the 700 soldiers and scouts who had gone out to wage war, 268 were slaughtered outright in the battle and 6 more later died from their wounds. It was a complete victory for the Native American tribespeople but it did not last; after the battle, immigrant Europeans continued to spread across the prairies and their superior arms soon gave them domination of the territory.

The digging at Como Bluff in the late 1890s gave rise to piles of dinosaur bones that could not be linked together, and, as the piles grew higher, thousands were used to build a small cabin. The cabin became a museum and soon had a petrol station erected nearby. As business diminished the property was sold off.

The vast central plains of North America extend over 800 miles (1,300 km) west of the Mississippi River to end abruptly against the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains that runs roughly north to south. The first time I travelled that route by road was 40 years ago. The barrenness of such vast areas of wilderness is overwhelming; occasional gateposts mark out the entrance to a ranch, and you know that the residents have to travel many miles to reach any other sign of civilization. Retracing the routes of the early pioneers, imagining their trekking ever westward with their dwindling supplies to reach the gold fields of California, it is hard to imagine the incredible hardship they had to face. Life for the indigenous tribes, who had existed in these desolate areas for tens of thousands of years, is unimaginable. There are other areas of today’s U.S. with limpid streams and clear rivers, soft hills and verdant valleys, inlets and creeks, lakes and natural meadows, where prehistoric people had made an easy living by gathering fruits, hunting, trapping and fishing. But the great plains are desolate. There is no water, little vegetation, and the scrub extends for hundreds of miles. From time to time a pool or a small lake appears to offer relief, but this is deceptive, for the water is often poisonous. These small lakes seem fringed with what appears to be white sand, but that ‘sand’ is comprised of chemical crystals. These lakes are concentrated solutions of soda – sodium carbonate, Na2CO3 – which crystallizes out as a natron, a white powder. The hopes of adventurers, seeking a supply of fresh water to drink as they passed through the western plains, were quickly dashed as these corrosive, alkaline pools of poison were all they found. Wagons passing through had to haul everything the explorers needed – dried food, fresh water – or they were doomed to die. Standing where they stood, I have experienced a deep sense of isolation and abandonment. These plains are not for the fainthearted. Life was easily lost in this wilderness.

Sedimentary rocks underlie these barren lands and date back to the late Jurassic period (156 to 147 million years ago). They are exposed along the front of the Rocky Mountains and extend out to the west as reddish-brown and yellow sandstones, siltstones and shales. These strata extend through 12 states, and they come to the surface mostly in Wyoming and Colorado, with outcrops in Idaho, Montana, North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and Utah. These huge deposits cover 600,000 square miles (1.5 million square km), though only a small proportion can be seen at the surface. They formed from material eroded from ancient mountain ranges far to the west, and deposited as sandy layers in great expanses of shallow lakes and rivers. Geologists categorize them as fluvial, floodplain, shallow lacustrine and even playa deposits – all terms that connote shallow expanses of water. Geologists believe that part of this vast prehistoric area was high in salt and soda and formed a vast stretch of water now known as Lake T’oo’dichi’ and covering much of the eastern part of the Colorado Plateau – it would have been the largest-known prehistoric alkaline, saline lake.8

Those distinctive sandy rocky strata were first described from exposures at Morrison, Colorado. This is a small, arty, cheerful town at the entry to one of the canyons cutting into the Rockies just west of the mile-high city of Denver. The town was named after George Morrison, the most prominent businessman in the area in the 1870s. Not only are the rocks readily recognizable, but they revealed an extraordinary range of dinosaur fossils. European explorers found bones protruding from the ground, emerging into the daylight after millions of years as rainwater weathered away the rocks. As we have seen, the fossils had been known about for thousands of years to the Native American population, who told legends of monsters like monstrous bulls and of mythical beasts like the gigantic bison named Ahke (the Cheyenne word ahk means petrified) that surely originated with fossils of Triceratops. As palæontologists were soon to find, there were abundant examples of these petrified dinosaurs. The entire area had once teemed with dinosaurs; their fossilized remains were not hard to find.

The strata of the Morrison Formation had been overlaid by younger sedimentary rocks in the Cretaceous period that began 147 million years ago. By this time the climate must have been becoming wetter; and, in contrast to the sandy-hued strata of the Morrison Formation, these early Cretaceous rocks are mostly grey, sometimes with a greenish tint. Above these fluvial and floodplain deposits is a vast layer of beach sand, the Dakota Formation, which is about 100 million years old, and which marks the transition from freshwater to the marine deposits that were laid down in a great seaway extending from the Arctic right down to the Gulf of Mexico. Geologists agreed that this colossal seaway had existed, though its origin remained a mystery for decades. It now seems that it formed when the cooling slab of the Farallon Plate beneath the Pacific Ocean sank down and was subducted beneath the western fringe of North America. In parts, this enclosed sea was deep; its seabed probably plunged down some 2,300 feet (700 metres) or more. Large shoals of prehistoric fish – some of them of monstrous size – congregated across much of its extent, and scattered fossils of the plesiosaurs which fed on them have been commonly found. This seaway reached its maximum extent about 75 million years ago, and it disappeared shortly after the end of the Cretaceous, about 64 million years ago. In the extensive shallow areas of this huge sea, colossal dinosaurs met and multiplied. Their bones lay tumbled across each other in the coastal floodplain’s mudstone, siltstone and sandstone – sediments that are reminders of the shallow waterways and lakes that once covered the area. The sediments from these shallow areas of sea yielded a treasure trove of dinosaur fossils.

The era of discovery was heralded by that most spectacular of astronomical events – the Sun disappeared from the sky. On August 7, 1869, a total solar eclipse swept across America. Its black shadow moved down across Montana and the Dakotas, touching Nebraska and on through Iowa. To the indigenous Native Americans it heralded disaster; and they were right. This was the time when their lands began to slip from their hands into those of the conquering Europeans. The eclipse heralded the end of their supremacy. It also marked the dawn of the great age of dinosaur discovery in the U.S., when an enthusiastic fossil hunter, Elias Root Beadle, a missionary from Philadelphia, came across the skull of a small dinosaur. Although he didn’t know it, this was going to make history. He sent the details to Marsh at Yale, but Marsh was too preoccupied to reply.

It was Beadle’s discovery that triggered the greatest wave of revelation that palæontology would ever know. When Beadle didn’t hear back from Marsh, after a decent interval waiting for a response, he tried writing instead to Cope. Spurred on by Marsh’s lack of interest, Cope had the fossil skull transported to him instead, and in 1870 he described it as a new genus, Lystrosaurus, from the Greek ɪstroʊ (listron, shovel) on account of its spade-shaped head. Marsh responded by setting out on his own voyage of discovery into the state on behalf of Yale, but nothing more was found. Exploration continued, and in 1877 a chance discovery triggered an explosion of interest. The Union Pacific Railroad Company had been constructing their segment of the Transcontinental Railroad and had met with the Central Pacific Railroad Company’s tracks at Promontory Point, Utah, in 1869. There were repeated raids by the Native American tribes and guards were posted along the new stretches of the railway line. One of the armed Union Pacific foremen, William H. Reed, liked to go hunting bison and deer in his spare time, and in March 1877 he set off on a raised line of hills north of the rail track a few miles east of Fort Fred Steele (near the modern town of Medicine Bow). Suddenly he came across some gigantic fossilized long-bones and vertebrae protruding from the ground. A lake nearby had been named Como (after Lake Como in Italy, which has a similar outline) and the blunt hill overlooking the vale became known as Como Bluff. Wherever he looked, Reed could see dinosaur remains sticking out of the rocks. Reed privately told his friend William E. Carlin, an agent for the railroad company, and for several weeks they forgot about hunting and started collecting fossils. They worked away for four months before news of their discoveries reached Marsh – and his interest was immediately aroused.

Meanwhile, Arthur Lakes, a part-time professor at what became the Colorado School of Mines, had found a huge fossilized vertebra between Golden and Morrison, just west of Denver. He sent details of his discoveries to Marsh. At the same time a school teacher and amateur fossil collector named Oramel Lucas, the first school superintendent of Fremont County, was exploring the rocky strata around Cañon City, Colorado, and soon started to unearth dinosaur fossils. He hauled five wagon-loads of massive rocks into the town and the fossils were put on display in a curiosity shop owned by Eugene Weston. Lucas contacted both Marsh and Cope, in the hope of being engaged to find more. Marsh ignored his letter, but Cope promptly hired both Oramel Lucas and his brother Ira and soon they discovered a damaged vertebra dug from strata at Garden Park, near Cañon City. It was one of the biggest such bones ever discovered. Only part of the vertebra, including a portion of the body, the neural arch and the spine, were found, and they showed how fragile the bones would have been. This dinosaur would have dated from some 150 million years ago, and Cope named it Amphicœlias fragillimus. The genus of this new dinosaur was named for the concavity of the vertebra, αμφι (amphi, both sides) and κοιλος (koilos, concave), and the species name is from the Latin fragillimus (most fragile). The entire vertebra was calculated to have measured 8 feet 10 inches (2.7 metres) tall and 4 feet 10 inches (1.5 metres) broad, making Amphicœlias not only the largest dinosaur yet found at the time, but the largest ever discovered to this day. Cope formally published his findings in 1877.9 That bone is now lost.

Some later calculations suggest that this monstrous beast could have been 190 feet (58 metres) long and weighed up to 120 tons, which makes it larger than the recently discovered titanosaurs. However, since the dimensions were based on relatively few bones – all those figures are conjectural.

It was now 1878, and by this time white people were everywhere across the Central United States, when another total eclipse of the Sun tracked its way across the dinosaur beds. On July 29, 1878, the Sun was again blotted out in a great swathe across Montana, Wyoming and Colorado, right across the regions where the greatest dinosaur discoveries in history were about to emerge. This time, with the Native American population largely subdued, it was widely observed by scientists. Thomas Edison, then aged 31, took a vacation in Wyoming specifically to observe and record the event. It was his way of proving his abilities, not just as an inventor, but as a serious scientist. As Edison was becoming the most celebrated inventor of his age, Maria Mitchell had become America’s most famous female scientist and was teaching astronomy at the all-women Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, Arkansas. Mitchell was not invited on any of the male-dominated scientific expeditions, so she resolved to set up her own and launched the world’s first-ever female team of female scientific observers.

An eclipse in that vast wilderness is an overwhelming spectacle – and it was one I also experienced in those latitudes almost one and a half centuries later when this book was being compiled. In August 2017, I drove 400 miles (640 km) across Colorado and Wyoming and stopped to observe the eclipse. The eclipse itself was a stunning and breathtaking experience. I have been present at two previous total solar eclipses; but this was the first where I was able to view it all in a completely clear sky. We all watched it in the middle of endless prairie that stretches for hundreds of miles, just scrub and occasional herds of bison – the buffalo of legend. Totality approached with the Sun now looking like the newest of new moons, and the lunar shadow could be seen to strike distant mountains on the western horizon, racing towards us at about 1,600 mph (2,500 km/h). As the last scrap of sunlight was shut off like a switch, the brilliant day was transformed to deepest night. All around, the distant sky at the horizon was red like twilight. Above, where the Sun once stood, was a perfect black disk from which hung gossamer wraiths like a bridal veil lacing into the sky. I took the chance to observe this soft silver crown through high-powered binoculars; you could only consider the strange thought that it’s always there anyway, this magical corona, but the brightness of the Sun prevents us ever seeing it. This reminds us of the power of the endless radiation from the Sun, that nuclear reactor hovering in our sky. The stars shone in the middle of the day. The air cooled dramatically. The ring of ghostly light that replaced the Sun hovered above us like a halo. Just 2 minutes and 28 seconds later the totality ended – those distant mountains were suddenly shining in bright sunlight and the curtain of bright light raced towards us across the prairie. Then a dazzling crescent of bright beads, like an eternity ring, suddenly emerged as the moon began to move away and sunlight flooded through the lunar valleys. They are known to astronomers as Bailey’s Beads (after Francis Bailey, the British astronomer who first described them in 1836) so – down with the binoculars. When you think of the way a hand lens starts a fire by focusing the sun’s rays on a newspaper, it reminds you of the danger of focusing sunlight on the retina of your eyes. Dramatically, everyone’s shadows reappeared. The day was a sunny summer day once again, and we were left speechless with the memory of that pearly ring hovering high in the sky where the Sun had been, just seconds before. I was following the tracks of the explorers who had found the first American dinosaurs, and the majesty of that spectacular event made one feel a tenuous contact with those pioneers and the Native American tribes who had once lived and thrived right across the continent.

Dinosaur hunters in the American midwest went fully armed against attacks by indigenous tribes. Othniel Marsh (middle of back row) was photographed with his fully armed team in 1872, though normally he left excavating to his agents.

While Cope had been working on the fragmentary remains of his giant sauropod Amphicœlias, Marsh was presented with a far more rewarding find in Como Bluff, Wyoming, in 1879. His team had found the skeleton of a 40-foot (12-metre) sauropod that was almost complete. He named it Apatosaurus. The name derives from the Greek ἀπατηλός (apatēlos, deceptive) and σαῦρος (sauros, lizard). He used that irreverent term ‘deceptive’ because the chevron bones on the underside of the tail are like those of a mosasaur but are different from those of their distant cousins, the giant dinosaurs. This fine skeleton was found in the Rocky Mountains in Gunnison County, Colorado. Two years later, the virtually complete (but headless) skeleton of a still larger individual was excavated at Como Bluff, and Marsh – who was convinced that this was a different dinosaur – decided to name it Brontosaurus excelsus. A geologist named Walter Granger found a further example at Medicine Bow, Wyoming, in 1898; but there was a problem. Although it was nearly complete, the feet and the skull were nowhere to be found. Marsh surreptitiously added some sauropod feet that had been found nearby and topped off the skeleton with a made-up skull based on the ‘biggest, thickest, strongest skull bones, lower jaws and tooth crowns from three different quarries.’ Although it gave Marsh the satisfaction of seeing a completed mount, he knew it was not faithful to the original. The skull was conjecture. He had made a mistake as serious as Cope had done with his own elasmosaur skeleton: Cope had placed the skull at the wrong end, Marsh had the correct end, but the wrong skull! Controversy continued to surround the identity of these fossils, and many skeletons that were labelled Brontosaurus were subsequently classified as Apatosaurus instead. Because of the confusion, palæontologists decided that there was no such genus that could reliably be identified as Brontosaurus, and this genus remained invalid (to palæontologists) throughout the twentieth century. Thus, one of the best-known dinosaurs in the minds of the public was a fiction to science.10

Palæontologists from the Carnegie Museum subsequently discovered two more of the brontosaur skeletons in Dinosaur National Monument in Utah, and the matter was reconsidered. A paper published in 1975 showed that the skull Marsh had found actually came from Camarasaurus, a dinosaur that had an altogether larger head.11

The Reverend Henry Neville Hutchinson published Extinct Monsters in 1897. Plate IV is a vivid portrayal of ‘A gigantic dinosaur, Brontosaurus excelsus’ by Dutch artist Joseph Smit. Other artists were to use his picture as a reference source.

Because there was always uncertainty about the skull Marsh had used, some drawings of a brontosaur show that the artist was careful to indicate its outline by dotted lines. John S. McIntosh of Wesleyan University and David S. Berman of the Carnegie Museum were the palæontologists who eventually proved that the skeleton had the wrong skull. Between 1915 and 1937, the cast of the brontosaurus at the Carnegie had been correctly displayed, without any skull at all. The director of the museum, W.J. Holland, wanted to give it the skull of a diplodocus, just to make it look complete, but as soon as the president of the American Museum of Natural History, Henry Fairfield Osborn, heard about the idea he objected strongly, and the idea was abandoned. In 1937 the museum finally decided to make the skeleton look whole, so they added a cast of the Camarasaurus skull. ‘Marsh needed a head, so he guessed,’ said McIntosh later, at the public unveiling of the corrected skeleton in October 1981. ‘Most of his guesses were remarkably good, but this one was not.’ The New York Times reported that Karl Waage, director of the Peabody Museum, conceded that it would be ‘Nice to get the right head on.’12 Outside the museum in Yale, T-shirts were on sale bearing a picture of the new skeleton with the caption: ‘I lost my head at the Yale Peabody Museum.’ It had taken almost a century for this mistake to be corrected. The Field Museum, Chicago, subsequently swapped their incorrect skull for a plastic replica, though the William H. Reed Museum of the University of Wyoming in Laramie said they would leave theirs untouched.

Meanwhile, eager to match his rival’s success, in 1870 Cope had decided to explore in Kansas. His mentor Leidy had made some important discoveries there, and Marsh had already been out exploring the rocky strata and inquiring in quarries. Benjamin Franklin Mudge was one of the local palæontologists who had helped Marsh, and Cope quickly signed him up to help his own efforts. By this time, he was showing signs of becoming manic, ignoring the need for food and water and experiencing nightmares in which he saw dinosaurs attacking him from every side. So long as there was daylight, Cope was at work with his team, marching, exploring, digging. Eventually he collapsed with exhaustion and was bedridden for weeks. Out west, meanwhile, work proceeded on the great Transcontinental Railroad, and the navvies were now turning up fossils as they excavated great cuttings through the mountains. Although these fossils were regarded as curiosities, there was no palæontologist around to evince interest, and so they were doomed to be discarded or destroyed. But word of the discoveries percolated towards the east coast, where the palæontologists began to wonder whether they should become involved. In those days, it was not so easy to travel westwards on a whim. The sites were not only some 2,000 miles (3,200 km) away from the universities across barren prairie, but were a mile (1.6 km) high. Cope managed to secure an honorary position with the U.S. Geological Survey under the direction of Ferdinand Hayden. Although it offered no personal salary, the post did involve travel to the sites of the new excavations where the dinosaurs had reportedly been discovered, and most of his expenses were paid. The fact that Cope wrote with flair and rapidity was perfect for Hayden, because he was keen to make a good impression with a series of vivid official reports. It worked for Cope, too, for this gave him the ideal outlet to publish his discoveries.

Cope launched his first expedition for Hayden in June 1872, heading out to survey the Eocene strata in Wyoming in which Joseph Leidy had already made several discoveries. This caused a break with Leidy, whom Cope had always admired so much. Hayden had always referred any new discoveries to Leidy, but the new situation meant that Cope now took charge. Leidy wrote immediately to Hayden to express his annoyance at being summarily replaced, but was told that there was little anyone could do. Cope’s new job description was to carry out geological surveys, and faithfully to report what he found; he could not be prevented from doing so. Cope moved his family out to Denver, so that they would be closer to where he was surveying, while Hayden sought a way to keep him from prospecting in the areas where Leidy had already been working. Both men were eager for pointers as to where the next discoveries might be made, and one day a geologist named Fielding Bradford Meek sent a telegraph message to say that bones had been found where the railroad was being excavated near Black Buttes Station. When Cope arrived on site, he found part of the pelvis, some associated vertebræ and some ribs, so he decided it was a new dinosaur and named it Agathaumas sylvestris. This was a late Cretaceous dinosaur measuring 30 feet (9 metres) long and weighing about 6 tons. Cope was then expected to travel 100 miles (160 km) west to Fort Bridger, and quickly brought together a team with a cook and a local guide, together with three amateur palæontologists from Illinois. He didn’t find out at first, but two of his teamsters were privately in the pay of another palæontologist – Marsh was working nearby. These workmen had turned to Cope because Marsh was slow to pay, and they did not care for his lofty and suspicious nature. When Marsh learned what had happened he turned on the hapless teamsters, who assured him that he remained their main priority, and added that they had gone to work for Cope only to lead him away from the best specimens.

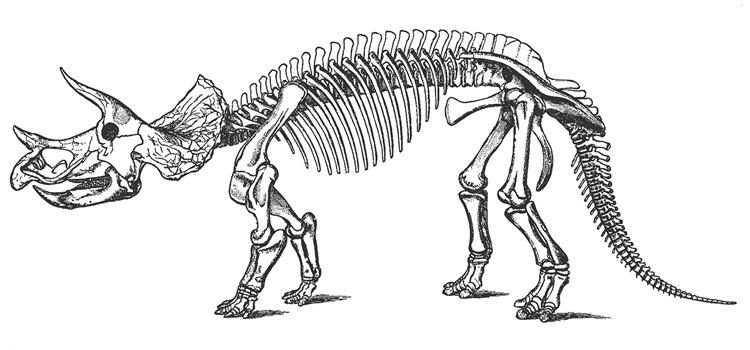

One day in 1872, a fragmentary fossil was brought in for Edward Drinker Cope to examine. It had been dug out of the Lance Formation, Wyoming, and consisted of several ribs and the pelvis of a heavy dinosaur. As usual, there was no skull. Ever keen to announce a new discovery, Cope named it Agathaumas sylvestris and decided it was a duck-billed hadrosaur. Not until 1887 was any more material found, when a geologist, George Cannon, and his team from the U.S. Geological Survey found some fragments of a fossil, and Marsh was given a piece of skull bearing two huge horns that had been unearthed near Denver. In typical haste, Marsh decided that – because bison roamed in that area – this must be a prehistoric version. He concluded that it was a Pliocene creature, which he named Bison alticornis. During the following months, Marsh was sent a few more samples of horned skulls, and he eventually decided that these belonged to dinosaurs. He named the ‘new’ genus Ceratops. The following year, Marsh obtained another specimen from strata next to those in which Cope’s first example had been discovered. This, he was now certain, was more Ceratops material. He quietly moved his earlier specimen over from Bison to Ceratops, transforming his mammal into a dinosaur in one stroke. Within a few months, he had changed that name too. All the fossils were now named Triceratops, the name we know today. After the first discoveries in Colorado and Wyoming, further examples were excavated in Montana and South Dakota in the U.S., and in the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. The original species was named Triceratops horridus by Marsh. The species name does not translate as ‘horrid’, as most people think; the Latin horridus means bristly. In time, many other species were named: one group was comprised of similar dinosaurs, T. horridus, T. prorsus and T. brevicornus, another group contained two species, T. elatus and T. calicornis, and there were two additional species, T. serratus and T. flabellatus. Others later added T. hatcheri, T. eurycephalus and T. obtusus – but most were based on fragmentary skeletons, some of which were probably younger or older specimens of the same species, and it was soon clear that the classification had been undertaken with undue haste. Recently, all have been reclassified by Catherine Forster, a taxonomist at the George Washington University, and they are currently placed in just two species, Triceratops horridus and T. prorsus. It also emerged that these two species were excavated from strata at differing levels, so these two dinosaurs never co-existed.13

One of the most startling discoveries made by Marsh was Triceratops prorsus, which was first thought to be a buffalo-like mammal. Marsh published this detailed figure as Plate XV in a paper for the American Journal of Science in 1891.

We now know Triceratops was a fearsome beast: its huge horns spanned over a yard (about a metre) and it weighed about 5 tons, so it was clearly able to travel on dry land. It is now one of the most easily recognized terrestrial dinosaurs, yet – though investigated first by Cope – the name we know today was eventually decided by Marsh. Such was the nature of their dinosaur rivalry. Cope’s team found many other dinosaur fossils that were entirely new to science. On one occasion, a crate of new finds that were meant for Marsh was sent, instead, to Cope. With commendable honesty, he forwarded them to the correct address, though Marsh remained obdurate. Throughout the 1870s, the three men – Cope, Marsh and Leidy – were all prospecting in roughly the same area. Priority became a problem, for they were often discovering the same species at the same time. When Marsh organized one of his prospecting trips from Yale in 1873, in addition to 13 students he had to travel with a platoon of soldiers as a show of force to the Sioux tribe. The students had to pay their own expenses, because previous trips had gone heavily over budget. In the future, Marsh decided to engage local enthusiasts to provide him with new fossils, while he worked through the vast amount of material he had already collected back at his office at Yale. Cope was also finding it increasingly hard to fund his expeditions, so he took a job with the Army Corps of Engineers. This gave him less freedom than he had previously enjoyed, but at least it kept him on site. In 1874, gold was discovered in the Black Hills of the Dakota territory. Marsh seized upon the extensive digging to see what fossils might be found, but tensions were running high between the American prospectors and the indigenous Sioux inhabitants. The solution was ingenious: Marsh would pay the Sioux people for any fossils they found, and, in exchange for their loyalty, he assured the chief that he would represent their interests at the Department of the Interior in Washington D.C.

For a decade Cope followed a rigorous schedule. Every summer he was out with his workers exploring for new fossils, and during the winter months he was busily writing up his discoveries for publication. He was in a perpetual battle against the academically minded Marsh and was determined not to be beaten. In 1874 Cope was signed up as geologist by the Wheeler Survey, a project led by George Montague Wheeler to map areas of the Western United States. In New Mexico, Cope discovered that neither Leidy nor Marsh had preceded him, so he was able to make a range of new discoveries. As a member of the survey team, Cope discovered that he had an added advantage – his findings were to be routinely printed, so he no longer had to pay for publishing. The rate at which he was publishing new discoveries was sometimes one every week, and he is quoted as having published more than 70 papers in 1880 alone, reporting the fossil finds that his teams had made in Colorado, Kansas, Oregon, New Mexico, Texas, Utah and Wyoming. There was a problem in this, of course; his hasty writing and description meant that accounts were often inaccurate, his conclusions sometimes unreliable, and some of the scientific names Cope proposed for newly discovered dinosaurs were either changed or, in some cases, had to be withdrawn.

In 1875, Cope was greatly saddened by the death of his father Alfred, though his feelings were mollified when he discovered that he had been bequeathed a fortune amounting to $250,000 (today this would be around £8 million, or over $10 million). This gave him a release from the search for funding, and he was at last able to concentrate on his first published book celebrating his newly discovered dinosaurs.14

This prodigious report ran to 622 pages, including 57 engraved plates that are crammed with illustrations. Still his new discoveries came tumbling out. In 1877, he purchased a half interest in the American Naturalist so that he could control the rapid publication of the new discoveries that he was continually announcing. Cope wrote every report himself. Marsh, by contrast, was working in a formal academic framework and he had teams of underlings to do his writing for him. His publications were often drafted by associates and he had editors, referees, and all the academic checks and balances to make the task as pain-free and accurate as possible. He repeatedly suggested that Cope could not conceivably be personally producing papers with the dates he claimed. To him, it simply did not seem possible.

Amateur enthusiasts were now following the reports of these dinosaur discoveries in the press, and it was in 1877 that Arthur Lakes set out hiking near the township of Morrison, Colorado. Suddenly, he turned a bend in the trail and chanced upon some dinosaur fossils at the surface of the track. These were of types nobody had seen before, and Lakes was wise enough to know that. As a teacher, he knew that it was sensible to ask your peers for advice if you are working in an unfamiliar field, and so he sent a letter to Marsh, describing a vertebra and humerus of a colossal ‘saurian’ skeleton that he had discovered. Returning to the site, he dug out some more huge bones, none of which he recognized. Marsh, as was so often the case, took time to respond, so Lakes – concluding that Marsh wasn’t going to be interested – sent a consignment of his new finds to Cope. Cope read the letter with interest, and when the news came out, Marsh immediately wired over $100 with the strict instruction that the matter was to be kept a secret. Lakes wrote back to say that he had also written to Cope, whereupon Marsh immediately dispatched an agent to Colorado to make sure that his claim was protected and to offer money for any new finds. Meanwhile, Cope had received a letter from O.W. Lucas, a botanist and amateur geologist, with news of yet another dinosaur site at Cañon City, Colorado, and was quick to ensure that Marsh could not interfere. Needless to say, Marsh was trying to claim that for himself too.

This continuing tit-for-tat continued every time something new was unearthed. It was the greatest personal rivalry ever seen in palæontology. The news soon spread that the two palæontologists were at war, and that there was money to be made, so the attitude towards these strange new fossils dramatically changed. Railroad workers now began to keep their eyes peeled for anything that might be of interest to the palæontologists. The Laramie Daily Sentinel was eagerly following the story, so when local workers told reporters of their fossil finds, they exaggerated the prices that Yale had been paying for the fossils. Cope was quick to react, and sent out an agent of his own, but it was not a success. The deal struck with Marsh had made the workers greedy, and Cope could not pay as much as they now wanted. Undeterred, he had his own agents recruit a new team of workers to go to Como Bluff in Wyoming and carry out excavations of their own. This historic site became the hub of the ‘bone wars’ when some of the team working for Marsh defected and began excavations for Cope.

There were now two nearby teams, both assiduously searching for fossils and each trying to sabotage the work of the other. When workers on the Union Pacific Railroad reached Como Bluff, they found strata that were rich in astonishing fossils. Without disclosing their real identities, and using false names, two of the workers sent word to Marsh that they had found huge reptile fossils. They did not disclose precisely where these were, but asked if Yale University would be interested, and how much money they might offer. The letter added that, if Marsh felt unable to agree generous terms, then the men would write to Edward Cope. This was too good a chance to miss, so Marsh again dispatched his agent to agree a contract for the rights to any exciting discoveries and to purchase the rocky strata outright. To this day, it is the name of Marsh that is attached to these startling new revelations – even though it was not Marsh who made the discoveries.

The reports from America had meanwhile reignited the search for fossils in Britain. Great Quarry in Swindon, Wiltshire, had been used for centuries as a source of clay and building materials. Quarrymen used to sell the fossil shells they found as a sideline, and many of them had personal collections of curious shells. The strata at Swindon represent the bed of an ancient sea dating back 147–142 million years, late in the Jurassic period. Layers of sediment slowly built up over thousands of years, showing phases when the sea was replaced by a freshwater lake, and other times when it was transformed into an inland salt lake like the Dead Sea with high concentrations of dissolved sodium chloride (NaCl). The pebbles at the bottom of the water were eroded and stratified, and the strata were littered with shells. From time to time, bones from a fossil were excavated. And so, on the morning of May 23, 1874, workers reported to their manager that they had found some remarkable fossils that seemed too important to ignore. James Shopland, the manager of the Swindon Brick and Tyle Company, sent word to Richard Owen that his workers had unearthed some curiously large bones. Owen’s palæontologist William Davies arrived on the scene to find bones protruding from a lump of hardened clay some 8 feet (2.5 metres) tall. They tried to winch them out of the ground, whereupon the mass broke into several fragments. They were all labelled and packed in crates that weighed a total of 3 tons. Owen put his most experienced excavator onto the task, a stone-mason named Caleb Barlow. At the middle of the mass was the pelvis of a large dinosaur with 6 posterior dorsal vertebræ, a full set of the sacral and 8 anterior caudal vertebræ, with several other bones scattered through the clay. The huge right femur (hip bone) was present, and so was the left forelimb. Barlow also revealed a damaged piece of the tibia and fibula of the lower leg with bones from the foot, a bony plate (from the right-hand side of the neck) and a strange spike.15

Owen described the creature in 1875 and originally named it Omosaurus armatus, though the generic name was subsequently changed to Dacentrurus because Omosaurus was already being used to describe a type of fossilized crocodile. This new discovery proved to be a stegosaur, the first such dinosaur ever to be discovered. The skeleton was reasonably well understood, though Owen wrongly concluded that the spike was part of the shoulder. We now know that it actually came from the right-hand side of the tail.

We have seen that the horn which Gideon Mantell had placed on the nose of the iguanodon was also in the wrong place, and it was a remarkable discovery in a Belgian coal mine in 1878 that was to prove the point. I first went to Bernissart in Belgium as a schoolboy; it is a former coal-mining town near the border with France. It remains largely unknown to the world at large, though everyone there knows about Iguanodon. Carboniferous plant fossils were regularly discovered in the seams, as they always are in coal mines. Miners used to find fossil ferns, or the impressions of cycad leaves, all beautifully preserved. On February 28, 1878, two miners, Alphonse Blanchard and Jules Créteur, were working 1,056 feet (322 metres) below ground level when Créteur called out: ‘I have struck gold!’ They had cut into a seam which contained what they took to be a golden tree trunk. On closer inspection it looked more like a large dinosaur bone. It was encrusted with fool’s gold (iron pyrites, FeS2) and it glistened in the light of their lamps like burnished brass. The supervisor of the mine, Alphonse Briart, recommended that a geologist should be consulted.

It did not seem possible that the fossil was a dinosaur bone: the coal measures were laid down during the Carboniferous period between 359 and 299 million years ago (remember that the name Carboniferous is derived from the era of coal-building), whereas dinosaurs existed between 243 and 66 million years ago, so they were on the scene 56 million years too late to be found in any coal seam. A telegram was sent to the Royal Belgian Museum of Natural History in Brussels, and the specialist brought in to examine the site was a palæontologist, Louis de Pauw. In May 1878 he began to extract the fossils from the mine and they were packed into 600 heavy crates and shipped to Brussels. What he found at Bernissart was phenomenal, and we have rarely seen their equal in the history of science. A large number of fully grown iguanodon skeletons were discovered, all tightly crowded together. When the bones were separated out, they were moved to the chapel at the Palace of Charles of Lorraine near Brussels to be reassembled – it was the only building tall enough to accommodate the height of the dinosaurs. The task of reporting on the remains and reconstructing the skeletons fell to Joseph Dollo, born in Lille in 1857. With valuable input from correspondence with an Austrian colleague, Othenio Abel, Dollo was the first to recognize that fossils should be considered as part of an entire ecosystem, and he first laid down the principles of a new science: palæobiology.

Bones of Dacentrurus, a large stegosaur originally dubbed Omosaurus, were formally described by Sir Richard Owen in 1875, as Plate 70 in his book A History of British Fossil Reptiles. This 8-metre (26-foot) long dinosaur weighed about 6 tons.

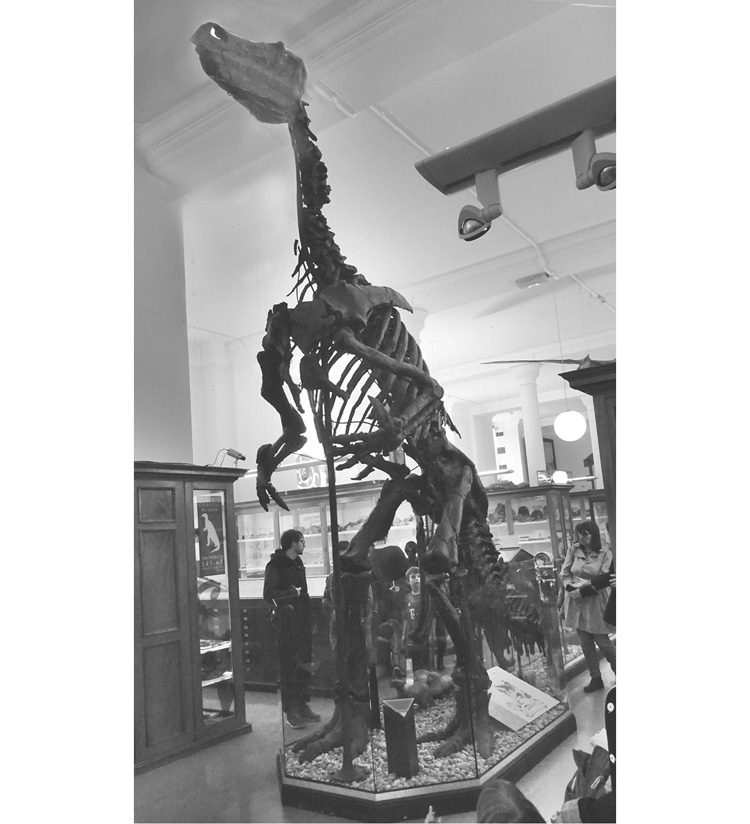

Dollo’s work began in 1882 and the remains of more than 30 iguanodons were eventually retrieved. Later that year the first of the skeletons was cleaned and any fragmented bones were stuck together by animal glue, before being assembled in an upright position, like a bear hugging a tree. In July 1883, people were admitted for the first time to view the fossils. The skeletons caused a sensation. They were later moved to the Royal Belgian Museum of Natural Sciences in 1891, where they remain on display to this day. The new species from the mine was found to be taller and more robust than the original Iguanodon mantelli (since renamed Mantellisaurus atherfeildensis, incidentally); Mantell’s iguanodon was less than 16 feet (about 5 metres) tall, whereas the newly discovered skeletons from the mine all measured more than 20 feet (6 metres), and the tallest of all reached 24 feet (7.3 metres) from nose to tail. The new species was announced as Iguanodon bernissartensis. Nine of them are displayed in glass cases in the Brussels museum, all standing tall as originally constructed, and there are 19 more in the basement. Casts were made of the skeletons, and a replica of one stands in the Natural History Museum; another is near the entrance lobby of the Sedgwick Museum in Cambridge, and there is also one in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. They are remarkable skeletons, and most are complete. The fact that so many of the skeletons were virtually entire and were still in their original configuration proved to be of crucial importance to the palæontologists, enabling Dollo to report on the strange spike that Mantell had put onto the snout of his iguanodon. The Belgian fossils confirmed that it really belonged on the forelimb, rather like a pointed thumb. Dollo mounted all these skeletons as if about to climb a tree, and they are so fragile that they remain in that position even though later work showed that the tail would not have been sufficiently flexible. Present-day reconstructions of Iguanodon have the spine parallel to the ground, not at right angles to it.

More than 30 Iguanodon skeletons were found crowded together in a Belgian coal mine in 1878. They were so complete that the correct position of the horn (which Mantell had assumed belonged on the snout) could finally be revealed.

The way that these iguanodons were crowded together initially led investigators to conclude that they were herd animals that had been drowned in a flood or some other disaster, but later it appeared that they had become trapped, one by one, in a fissure that had opened up into a pre-existing coal seam. The existence of pyrites in the fossils soon caused problems. As it oxidized in contact with fresh air it started to crumble, so in the 1930s the skeletons in Brussels were all impregnated with shellac and arsenic, which bound them together in a gluey mass. Needless to say, this didn’t last, so in 2003 the bones were cleaned of the glue and shellac, and impregnated instead with cyanoacrylate and epoxy resin. It is hoped that this will suffice for a much longer time.

King Leopold II arranged for a plaster cast of the finest of the Bernissart iguanodons to be donated to the Sedgwick Museum of Cambridge University. It greets visitors to this day, still in its original upright pose, near the entrance.

While that activity was creating news in Europe, another extraordinary discovery was making headlines in America. In 1877, in the mountains of Colorado, Arthur Lakes (a name you rarely find in accounts of dinosaurs) coined the name Stegosaurus. In the early spring, just as the snows were melting, he was looking at exposed rocks in the quarries of the Morrison Formation in Colorado – rocks of precisely the same vintage as the pebbly clay in Swindon’s Great Quarry – and came across a strange skeleton with those huge protective plates clustered around its spine. He couldn’t believe his eyes. Massive skeletons he had already found, but this was something different. Here was a dinosaur with massive plates down its back, like a reinforced rhinoceros. As soon as the news was out, the representatives from Yale descended on the site, paid handsomely for the fossil-bearing rocks and packed them securely in straw-lined crates for shipment back to Marsh. Once the crates were opened, the bones were quickly exposed to reveal a huge creature adorned with bony plates along its back and a spiked tail. In 1878, Marsh announced the new discovery. Following the discovery of the Dacentrurus in England, this was the second genus of the stegosaur family to be known to science. Since then, the existence of these monsters has been associated with Colorado and the name of Othniel Marsh, while the true story of their earlier discovery in England has been forgotten. The reconstruction that Marsh proposed was wrong. Because of the watery environment indicated by the sediments in which the skeletons had been found, he assumed that these creatures were some kind of turtle. He named this dinosaur as he did because he completely misunderstood how the dinosaur had looked. He believed that the plates lay flat on the back, like the shingles or slates on a roof, so that the creature was like a huge tortoise. The name Stegosaurus reflected this belief in a domed protective carapace: it came from the Greek στέγη (stego, roof) and, of course, σαῦρος (sauros, lizard).

A complete skeleton of Stegosaurus ungulatus was published by Othniel Marsh in 1891. He showed the 8 tail spikes correctly and adorned the spine with 12 plates. Later studies showed that there must have been a double row of dorsal plates.

Meanwhile, Marshall P. Felch had been prospecting for dinosaurs near Cañon City. Felch was a shoemaker from New England who became fascinated by dinosaurs and excavated fossils in a quarry to the west of Pueblo, Colorado. In February 1883 Marsh had written to him, asking if he could agree to undertake excavations exclusively for Yale. He would be well paid for his work. This provided Felch with the financial security he needed, and proved to give Marsh the opportunity to introduce a range of new dinosaurs to science. Some 65 dinosaurs were discovered in the Marsh-Felch excavations. Most of the remains were scattered bones, many of which were unearthed where there had been a particularly deep area of water, but among them were several near-complete skeletons. In 1886 Felch dug up a beautifully preserved specimen of Stegosaurus. It was lying on its side, as though squashed flat, and it has been nicknamed the ‘road kill’ dinosaur. This skeleton confirmed how the bony plates lay along the spine, like a ridge, and were not laid flat on the back like a stony shell. The specimen that Felch discovered is the type specimen for Stegosaurus stenops, and more than 50 partial skeletons, including several with skulls, have since been found across Colorado, Utah and Wyoming. As our knowledge increased with the new finds, one particular problem began to present itself: the bony plates, if you lined them up along the spine, were too numerous to fit into the available space. There must have been two rows of plates running side by side along the animal’s back. Even now, our concept of the stegosaurs’ anatomy may not be correct.16