1

Placebos

A Brief History

Two pieces of wood, properly shaped and painted, were next made use of. . . . In four minutes, the man raised his hand several inches, and he had lost also the pain in his shoulder usually experienced when attempting to lift anything. He continued to undergo the operation daily, and with progressive good effect; for on the 25th he could touch the mantle-piece.

This patient at length so far recovered, that he could carry coals and use his arm sufficiently to assist the nurse; yet previous to the use of the spurious Tractors he could no more lift his hand from his knee than if a hundred weight were upon it, or a nail driven through it. . . . The fame of this case brought applications in abundance; indeed, it must be confessed, that it was more than sufficient to act upon weak minds, and induce a belief that these pieces of wood and iron were endowed with some peculiar virtues.

—John Haygarth, Of the Imagination, January 1, 1800

It was New Year’s Day, 1800, and Haygarth, a noted physician and student of William Cullen, famed first physician to the king of Scotland, had an axe to grind.1 On retiring to Bath after a brilliant career in medicine, Haygarth had grown increasingly appalled at the popularity among the wealthy elite of two small handheld devices touted to have extraordinary curative powers.2 Known as Perkins’s tractors, the metallic rods were a US import. By simply drawing the tractors over an afflicted body part, Elisha Perkins, their inventor, claimed to be able to remove rheumatism, gouty affections, pleurisies, inflammation, epileptic fits, lockjaw, and pain and swelling from contusions, sprains, burns, and headaches. Not even Haygarth, who would put the tractors to the test, could dispute their effectiveness.

Perkins (1741–1799) was a Yale-trained physician who was himself the son of a physician. During oral surgeries, he observed that contact with metal could induce focal analgesia and make muscles contract. He fashioned a pair of three-inch metal rods to see if they might have a curative effect on his patients. His early tests were so positive that he took out a patent, and as was the custom of the day, named the invention after himself. Perkins and his Perkins Patent Tractors gained rapid popularity (figure 1). The rods were rounded at one end and sharpened at the apex; one was made of silver and platinum, and the other was made of copper, zinc, and gold. They cost only a shilling to make and sold for a whopping five guineas (around five hundred dollars) a pair. Buoyed by his success, he presented his invention at the Connecticut Medical Society meeting of 1795, ascribing the tractors’ healing powers to galvanism and the newly discovered therapeutic effects of electric currents. Perkins was greeted with derision and a wall of skepticism and soon after left Connecticut, taking his invention to Philadelphia, the then US capital, where Congress was in session. There the tractors continued to grow in popularity. George Washington purchased a pair, and the Honorable Oliver Ellsworth, former chief justice of the Supreme Court, wrote to the Honorable John Marshall, the sitting chief justice, remarking, “The effects wrought are not easily ascribed to imagination, great and delusive as is its power.” But Perkins’s personal success would be short-lived. When yellow fever broke out in New York City, Perkins claimed to have discovered the cure. In 1799, armed with a tincture of vinegar and muriate of soda, he headed to New York. There he feverishly administered his antiseptic for four weeks before he himself contracted the virus and died. By the time of Perkins’s death, however, the tractors were well on their way to the elite summer circles in Bath.

Figure 1 Cartoon sketch by James Gillray, 1801, of a quack treating a patient with Perkins Patent Tractors.

Haygarth was a man of reason. His advocacy of smallpox vaccines is credited with reducing the spread of the disease in late eighteenth-century Great Britain. As a student of Cullen, Haygarth would likely have been familiar with the great physician’s teachings on use of a “pure placebo” (a bread or sugar pill), or lower doses of regular drugs to please, palliate, or “give what might be of use to the patient.”3 But palliative placebos administered by caring physicians were one thing; patent medicines like Perkins’s tractors were entirely something else. As Haygarth wrote, the tractors, having “obtained such a high reputation at Bath, even among persons of rank and understanding,” required the discerning attention of physicians.4

In deciding on a process to investigate the tractors, Haygarth had a compelling precedent. Just over a decade earlier in 1784, an all-too-similar outbreak of marginal science had infiltrated elite Parisian circles. The inventor was Franz Anton Mesmer, a successful Austrian physician. Having used magnets to cure a young woman of a host of maladies including fevers, vomiting, toothaches, and intermittent paralysis, Mesmer hypothesized that a fluid, which he named animal magnetism, penetrated and encircled all bodies, and could be used to heal patients. Mesmer and mesmerism, as his technique came to be called, gained fame and fortune as he wielded a large metal rod over patients to move the fluid in the service of healing. At the time, Mesmer’s techniques and their apparent theatrics gripped even the upper echelons of French society. Demand grew, and he scaled up his operation with the invention of a “baquet,” a large oak tub filled with “magnetized” water from which iron rods protruded. Scores of patients encircled the baquet, gripping the iron rods, pressing against each other to allow the magnetic fluid to flow. As incense and empyrean tones wafted through the air, patrons would fall into “crises” resembling violent convulsions. Piercing shrieks or bouts of laughter erupted as the patients juddered back to health. Despite the fact that his wife, Marie Antoinette, was a frequent baquet flyer, or perhaps because of it, King Louis XVI yielded to pressure from the medical establishment to investigate Mesmer.

To lead his Royal Commission on the danger to the public morals posed by “animal magnetism,” Louis XVI tapped the distinguished and beloved US ambassador to the French court, Benjamin Franklin. Franklin was joined by an all-star team of distinguished scientists including Antoine Lavosier, the “father of chemistry,” Jean-Sylvain Bailly, a famous astronomer, and the physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, who also happened to be a strong proponent of the rapid decapitation device that later would bear his name.5 While the Royal Commission claimed its sole interest was evaluating animal magnetism, its commentary as it started its investigations suggested that there were deep concerns that should the practice of magnetism take hold, “the whole science of medicine would become useless.” The commissioners spent three to four months conducting what might be considered one of the first clinical trials. Franklin hosted some of the simulated sessions at his home in Passy. At Franklin’s lead, the commission created sham mesmerized rods and water. He had imposters pose as practitioners. They witnessed firsthand the crises wrought as their placebo controls incited the same group dynamics that the true mesmerists induced: participants convulsed, retched, and screamed—sometimes for hours. In the final analysis, Franklin and the commission concluded that while mesmerism did indeed elicit the striking effects for which it had become known, the same effects were induced with fake objects and sham practitioners.

Haygarth versus Perkins: Another Early Clinical Trial

Franklin died in 1785, some years before Haygarth launched his investigation into Perkins’s tractors. But it’s easy to see Franklin’s influence on Haygarth in the use of sham devices as controls in his tractor trial. Haygarth was well acquainted with Franklin and his work. The two men had corresponded by mail, with Haygarth sharing guidance on how inoculations could prevent the spread of smallpox in the United States. Franklin’s second son, Franky, had succumbed to smallpox at the age of four, making Franklin a strong proponent of inoculations to stem the spread of the disease. So much so that in his autobiography, Franklin is famous for lamenting that he “long regretted that [he] had not given it to him [Franky] by Inoculation.”6 Haygarth was likely also influenced by Arthur Lee, a protégé of Franklin whose help he enlisted in designing the Perkins’s trial. Lee was likely familiar with the dummy rods and sham mesmerists that Franklin employed to test whether animal magnetism really worked.

Haygarth fashioned sham Perkins’s tractors of wood, and painted them gold and silver so no one would be the wiser. He sent these out to other physicians with strict instructions that patients be unaware of the ruse. His 1800 manuscript detailing the results of this study, titled Of the Imagination, as a Cause and as a Cure of Disorders of the Body; Exemplified by Fictitious Tractors and Epidemical Convulsions, would be widely disseminated, rivaling the popularity of the tractors themselves.7 The cases reported in the manuscript were and still are today nothing short of remarkable. Take, for instance, one Thomas Ellis, who was so severely afflicted with rheumatism that he was unable to walk without support or feed himself for months. On being treated with the wooden tractors, he felt his skin growing warmer with occasional darting pains and throbbing on a cicatrix. After ten days of sessions, he was able to comb his hair, put on his jacket, and walk across the ward without a stick or the least assistance. In this manner, patient after patient was restored to health. Thus, Franklin and Haygarth came to the same conclusion. Their key finding was not that these strange and bewildering remedies didn’t work; it was that the sham devices worked just as well as the real ones.

Franklin and Haygarth came to the same conclusion: not that these strange remedies didn’t work, but that the sham devices worked just as well as the real ones.

The efforts of Franklin and Haygarth to stem the growing popularity of nostrums and patent medicines would be in vain. Despite the discovery of the pathogenicity of microbes and disease preventive effects of pasteurization and vaccines in the mid-1800s, clinical objectivity would be slow to take hold. Another century of rampant quackery would pass before “regular” or “orthodox” physicians would gain enough power to curtail the charlatanry.

Integrative Medicine

Part of the popularity enjoyed by quacks in the nineteenth century was driven by fear of so-called regular physicians. Regular was the term given to physicians educated at university-affiliated medical colleges. They were classically trained to use heroic medicine—bleeding, sweating, and emetics—to shock the body back to health. With this limited approach, it is not surprising that the milder “irregular” physicians, including mesmerists (later renamed hypnotists), water cure specialists, and homeopaths, remained popular among the public. Many of these milder therapies had much to recommend them, and their popularity would endure into modern times. In various forms, some of these treatments—hypnosis, homeopathy, and hydrotherapy—are now practiced under the umbrella of integrative medicine.

Hypnosis, or the induction of a trancelike state in which the subject is highly responsive and susceptible to suggestion, is a commonly used therapeutic technique in the treatment of pain and psychological challenges, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress syndrome. The technique is thought to have partially been inspired by the theatrics of Mesmer and mesmerism and was briefly used in place of anesthesia for surgeries in the nineteenth century.8 Much later, hypnosis re-emerged as a respected technique used among psychologists. In 1958, the American Medical Association (AMA) approved a report that stated that there were “definite and proper uses of hypnosis in medical and dental practice.”9 This support was later echoed by the American Psychiatric Association and a National Institutes of Health panel of experts, and the topic remains of interest among clinicians, social psychologists, and neuroscientists alike.

Founded by Samuel Hahnemann (1755–1843), homeopathic medicine is based on the “principle of similars”: a condition can be cured with a treatment that induces in a healthy person the very symptoms that afflict a patient. This principle of “like cures like” was derived from Hahnemann’s own experience inducing malarial symptoms of intermittent fever using bark from a cinchona tree, which, as it turns out, contains quinine. To minimize the toxic effects of some of his remedies, Hahnemann serially diluted the active agents in alcohol or water so that only a trace amount remained. Another notable feature of homeopathy is the typically hour-long consultation in which the patient’s life and illness are painstakingly discussed. In part because of its beneficial effects and enduring popularity, homeopathy would survive into the modern era despite the reservations of physicians educated in Western medicine, who remained skeptical about the efficacy of the infinitesimal.10

Hydrotherapy, or the so-called water cure, was an alternative treatment method that originated from the belief that pure water had significant healing benefits. Hydrotherapists administered the cure, water, through a variety of routes: patients would drink large quantities of water, sit in cold baths and use douches, and/or rub wet bandages and sheets on the body, all in combination with exercise and a simple diet. What these milder irregular therapies have in common is likely the ability to induce strong placebo effects.11 But not all therapies originating in this era were as benign.

Quacks, Charlatans, and Patent Medicine

Even clergy who had access to free care from regular physicians opted for irregular medicine techniques, including nostrums and tonics, lending their names and credibility to testimonials and advertisements, thereby reinforcing and driving the popularity of these treatments. Lumped in with the irregular physicians were the physician quacks. These were physicians who were either poorly trained or, as in the cases of Mesmer and Perkins, well trained only to go the way of proprietary medicine with an invention that exploited the placebo effect. There were also the quacks who claimed to be physicians, patenting or more precisely trademarking the name on the label as opposed to the formulation of the medicine. This was probably because patenting a product required disclosing its contents, and the contents of many, if not most, nostrums and tonics would have dissuaded any thoughtful consumer, as we will soon see.

Regular physicians were not allowed to advertise, and this put them at a tremendous disadvantage in relation to quacks who used flyers, magazines, religious and secular papers, and the press to appeal to sufferers of every ailment imaginable with an offer of a miraculous cure. The rise of medical societies and journals gave the regular physicians a platform from which to take aim at nostrums, quackery, and pseudomedicine. Regular physicians had already begun to consolidate their power during the American Civil War (1861–1865) by requiring medical examinations and degrees from proprietary medical schools for physicians to volunteer in the physician corps of the Union Army. Still in the 1800s, US patent medicines constituted 28 percent of marketed drugs.12 Aided by advertisements to the unwitting public and many a physician, this would grow to 72 percent by 1900.

Some of the more effective remedies were far from placebos. One of the most popular and powerful of these was Mrs. Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound, a women’s tonic for menstrual and menopausal discomfort. This tonic was composed of a mixture of herbs including an extract from the Jamaica dogwood distilled in alcohol. The bark of the Jamaica dogwood (Piscidia erythrina or Piscidia piscipula) is used in traditional remedies to treat pain, insomnia, menstrual cramps, anxiety, and fear. The bark contains rotenone, a compound that kills fish by impeding respiration, and its use was banned in the Caribbean, where fishers would throw it in the water to stun fish. The bottle featured an image of Mrs. Pinkham, always in formal dress, and hair parted down the middle with a Mona Lisa smile (figure 2). Her advertising campaign would position her company as one of the most successful patent medicine companies of the late 1800s and beyond her death into the early 1900s. Frozen in time and looking as surprised to see her as we are, Mrs. Pinkham appears on the packaging of her Herbal Tablet Supplement available on Amazon today!

Figure 2 Labels from Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound products, then (left) and now.

As residents of Lynn, Massachusetts, the Pinkhams tried to gain credibility by engaging nearby Harvard Medical School physicians to conduct a controlled study comparing the vegetable compound to a placebo control.13 While the Pinkhams wanted the researchers to use a water-based product as a control, the Harvard physicians argued that as the tonic was 18 percent alcohol, they would have to use the same amount of alcohol in the control. The studies were never done.

The Augean Stables

When the veil of mystery is torn from the medical figure the naked sordidness and inherent worthlessness that remains suffices to make quackery its own greatest condemnation.

—Samuel Smith, The Great American Fraud, 1905

Not all tonics and nostrums were as well conceived or well intended, and by the turn of the twentieth century, the harms, both financial and physical, were mounting. For the most part, quackery preyed on the hopes and desperation of an ailing public. The quack direct marketing process was simple. If you wrote a letter of inquiry in response to an ad, you would receive a seemingly personalized letter designed to build your expectations as well as convince you that the patent medicine was used to great effect by the inventor and other patients with symptoms similar to yours. These letters ended with the cost of the nostrums and a special deal, just for you, because the inventor was so concerned with your case. If you, as the potential patient, did not respond, another letter announcing a sudden fortuitous discount would be sent, and so on, until you, the prospective patient, took the bait and bought the mail-order treatment. There was little recourse after this; attempts to return ineffective or damaging treatments were met with complete disregard for the victim.

The press became dependent on the advertising money paid by patent medicine companies, and shied away from publishing reports that might draw attention to the damage being done to pocketbook and person. Because the US Postal Service was the mechanism by which letters, then money, and then goods were exchanged, not surprisingly it was the postmaster general working with the AMA that would eventually halt the flow of proprietary medicines.

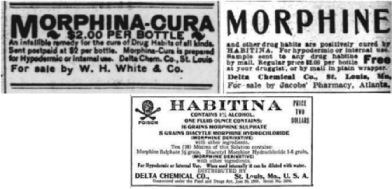

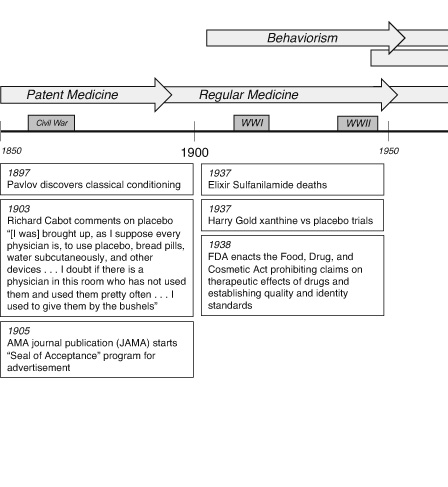

To discourage the production of fake or harmful medications, the AMA started a voluntary drug validation program in 1905 that would remain a requirement until 1955. For drugs to obtain the AMA Seal of Acceptance and be advertised in the Journal of the American Medical Association, they had to be assessed by the AMA’s Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry, proven to treat ailments as claimed, and shown to contain safe and high-quality ingredients. In 1905, the AMA also doubled down on quackery by republishing a series of articles by Samuel Smith that had appeared in Collier’s magazine titled “The Great American Fraud,” detailing the crimes and misdemeanors of “the nostrum evil and quackery.” The series sold tens of thousands of copies. Each article detailed the US Department of Agriculture’s chemical analysis of the patent medicine’s contents and ensuing legal proceedings against the proprietors. What emerged was far from a benign story of placebo effects. While Dr. Turner’s obesity cure was nothing but starch, ginger, talc, ash, and milk by-products, Dr. Curry’s cancer cures contained antiseptics, hydrogen peroxide, and preparations of opium and cocaine. Perhaps the most vicious were the business concerns that peddled the very ingredients that were the sources of people’s addictions. Dr. J. W. Coblenz was a case in point; his advertisements included a word of advice to the victim of morphine addiction that the way to conquer the habit was through persistence. All the while, the key ingredients in Coblenz’s No. 1 tonic were alcohol and morphine. Similarly, Habitina, touted as a gradual reduction treatment for addiction to pain-alleviating and sleep-producing drugs that did not poison the system like plain “morphin,” was in fact a combination of morphine and heroine that left the patients worse than they were before taking the treatment (figure 3). It is no wonder that placebos, ensnared in charlatanry, would take another hundred years to extricate themselves from this Augean stable.

Figure 3 Habitina labels over time. Habitina was a patent medicine sold as a cure for addiction to morphine. When the US Food and Drug Administration required the disclosing of contents on the label, Habitina was revealed to have morphine as an ingredient.

Regulatory Affairs

In 1906, the Pure Food and Drugs Act was passed by Congress. The terms for “adulterated” and “misbranded” were finally delineated, opium and alcohol were classified as dangerous ingredients, and drug labels to indicate the presence of these compounds were required. While quacks were required to state the contents of their treatments, regular physicians ironically had no such requirement in the dispensation of placebos. Despite this apparent contradiction, Richard Cabot confirmed this continued ubiquity of placebos in medicine in his 1909 review of “Truth and Falsehood in Medicine”: “I was brought up, as I suppose every physician is, to use what are called placebos, that is bread pills, subcutaneous injections of a few drops of water (supposed by the patient to be morphine), and other devices for acting on the patient’s symptoms through his mind.”14

It would take tragedy and an act of Congress to cement the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) control over the production and distribution of pharmaceutical drugs. In 1937, Elixir Sulfanilamide, marketed for treating a variety of infections from strep throat to gonorrhea, left seventy-one adults and thirty-four children dead. Far from a placebo, the formulation included a commonly used antibacterial agent, sulfanilamide, dissolved in a deadly proportion of diethylene glycol (antifreeze). The lethal events shocked physicians and legislators alike, and at long last hastened the confirmation of legally binding guidelines for drug production. In 1938, Congress finally implemented the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, introducing critical regulations on drug production and distribution, including proof of safety before distribution, and limits on the amount of poisonous matter in drug factories.

Emergence of Placebos as Controls in Clinical Trials

As the study of metabolism, physiology, and pharmacology were formalized as research disciplines in the 1920s and 1930s, the use of controls—especially placebos—in clinical studies became indispensable. When Harry Gold, a pharmacologist at Cornell University Medical College, began to investigate the use of xanthines to relieve cardiac pain in the 1930s, he was aware of the vagaries of placebo effects. He set about to screen out placebo responders by excluding patients who could not correctly attribute their pain relief to glyceryl trinitrate versus a soluble placebo taken under the tongue at the onset of an attack of pain. As many patients were unable to discern the difference between the drug and placebo, he was forced to abandon his screening effort. Gold enrolled one hundred patients who suffered from cardiovascular disease and heart pain in what would be one of the first n-of-1 studies in which the patients were their own controls, crossing over from xanthine to placebo and back throughout the course of the study. After five years, the study was completed in 1937 and found no difference between pain reduction with xanthine compared to the placebo. Impressed with the placebo effects in this and other studies, Gold, a pharmacologist, would become a strong proponent of the benefits of placebo therapy. By World War II, the use of placebos in blinded clinical trials would be well accepted, though randomization had not yet entered the equation.

In 1946, at the end of World War II, Gold joined Eugene Dubois and other scientists at the Conference on Therapy sponsored by Cornell University Medical College. This was the first conference where placebos were openly and actively discussed. But Gold’s positive view that “the placebo is a specific psychotherapeutic device with values of its own” was met with opposition on ethical grounds. Henry Richardson, a psychiatrist from Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, summed up the ethical concerns: “I don’t like the element of deception in a placebo, apart from the fact that it is disastrous to get found out. I think that if there is to be a deception it should be the one which the patient demands and which, also, I think he needs.”15 Again, the fault with placebos was not that they didn’t work but instead that they were linked to deception and relegated to the unethical.

The Declaration of Helsinki, written to address ethical practices for clinical research, built on the Nuremberg Code of 1947 to address human experimentation and other human rights atrocities committed in the name of medical research in Germany during World War II. If there was any hope to use placebos deceptively in the clinic, the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964 shut the door. Though the declaration itself was not legally binding for physicians, it marked a shift in the general perception of physicians and medical ethics, and contributed to a variety of legislations that strongly influenced the future of human subject research. Modern ethical practices are generally derived from the 1978 Belmont Report along with the work of Thomas Beauchamp and James Childress, who introduced the central ethical principles of respect for autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, and justice. Importantly, these new tenets of clinical and experimental ethics prohibited any form of deception of the patient. This policy posed a problem for physicians who had taken to prescribing placebos to hard-to-treat patients. Because it was believed that the treatment would not work if patients knew they were being given inert treatments, the question of using placebos in clinical practice was a nonstarter. Although the randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial would become the gold standard for evaluating the efficacy of drugs, it would take over a half century for researchers to formally challenge the requirement of deception for placebos to work.16

The Powerful Placebo

Henry Beecher, born Harry Knowles Unangst in 1904, was intimately aware of the power of information to shape expectations and perceptions. After college, a master’s degree in physical chemistry, and a name change, he left his home state of Kansas for the hallowed halls of Harvard Medical School. As Beecher, he graduated in 1932, and by 1941 was the first endowed chair in anesthesiology in the United States. When World War II broke out, Beecher served as an army physician on the front lines in North Africa and Italy. He witnessed firsthand how expectations of pain relief could ameliorate the suffering of soldiers wounded in battle, and on his return to Massachusetts General Hospital, focused his research on painkillers like morphine.17 Beecher became fascinated with what he called placebo reactors: patients who responded to the placebo controls. Although he was not at the Cornell meeting in 1946, his landmark paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association a decade later on Christmas Eve 1955 was a gift to the future of placebos. This modern formulation, fittingly titled “The Powerful Placebo,” was a tour de force of all things placebo. Beecher discussed their utility as psychological instruments in mental illness, a treatment to be used by the harassed clinician of the neurotic patient, and controls to eliminate bias and help in determining the effects of drugs. He summarized several earlier findings by other groups that pointed to the power of placebos to activate biological processes including the adrenals (the fight-or-flight response) in much the same way a drug could, arguing that the effects of placebo highlight a fundamental common mechanism that warranted further serious investigation. In what would be considered an early meta-analysis, he determined that 35 percent of people across fifteen studies responded to placebos. Although some researchers debate his methods, his finding is certainly in the ballpark of what is seen today in trials of chronic and functional pain conditions. He also listed thirty-five side effects observed with placebo treatment and exhorted the use of placebo controls in assessing efficacy as well as side effects. Beecher asserted that placebo and drug effects were additive, suggesting that excluding placebo reactors from studies would boost the difference between drugs and placebos.

Research on Placebos

Experimentation on placebos would continue through the 1960s and 1970s. These studies explored the role of conditioning and expectation in response to inert treatments. Although endogenous opioids were suspected as mediators of a placebo response, it wasn’t until Jon Levine and Howard Fields examined the influence of naloxone and opioid antagonists that there was confirmation of this hypothesis. They demonstrated that naloxone (trademarked as Narcan) blocked a placebo response after molar extraction, suggesting that opioid signaling might play a role in placebo responses.18 This finding showed that placebo effects have an objective, biological basis and thus changed physician’s impressions of the potential of placebos across the world. A new era of placebo research was about to begin.

Soon after, behavioral psychologists weighed in with theories of expectation and conditioning in the placebo effect. In 1985, Irving Kirsch posited that placebo responsiveness is a result of response expectancies that can affect experience, physiology, and behavior. Since then, there has been modest debate surrounding the relationship between expectation and conditioning, and the extent to which each contributes to eliciting a placebo response. By the 1990s, Fabrizio Benedetti, a neurologist in Turin, began a series of mechanistic studies that launched us into the modern era. These would set the stage for two decades of placebo neuroimaging studies that were set in motion by landmark papers in pain, depression, and Parkinson’s disease, and would transform the way we think about placebos today.19

Midway through, in 2010, Ted Kaptchuk and colleagues founded the Program in Placebo Studies (PiPS) at Harvard Medical School. This was the first multidisciplinary organization for placebo studies. Compared to previous placebo research, which was typically conducted by individual researchers in their area of expertise, PiPS assembled a team of clinicians, psychologists, anthropologists, philosophers, biologists, neuroscientists, and geneticists to conduct research that was translatable to the clinic. A few years later, in 2014, the Society for Interdisciplinary Placebo Studies (SIPS) was founded by some of the PiPS members and other leading international placebo researchers. SIPS is an international organization that promotes communication and collaboration between research centers and scholars in the study of placebos, use of multidisciplinary tools to investigate the psychological and physiological mechanisms of the placebo effect, and translation of these findings into ethical methods to utilize placebo effects in the clinic.

In Regione Vivorum

Since Mesmer versus Franklin and Perkins versus Haygarth, we have done an outstanding job separating clinically effective treatments from those that appear to have no benefit beyond that of a placebo. But like Franklin, Haygarth, and the many scientists and clinicians who followed, we have failed to focus on the most important part of the placebo puzzle: the patient. While the determination of safety is paramount and immutable, the determination of efficacy presents a different challenge. If both a placebo and verum pill, injection, or surgery equally reduce patient suffering with no difference in benefit, is it fair and reasonable to withhold both when there is no other option available?

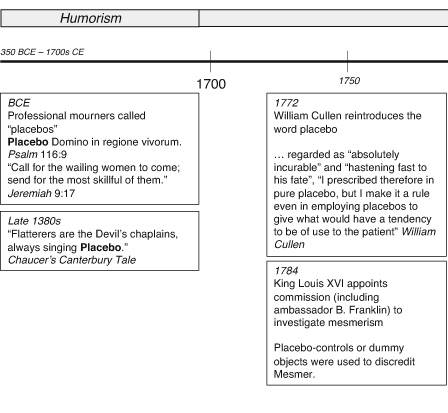

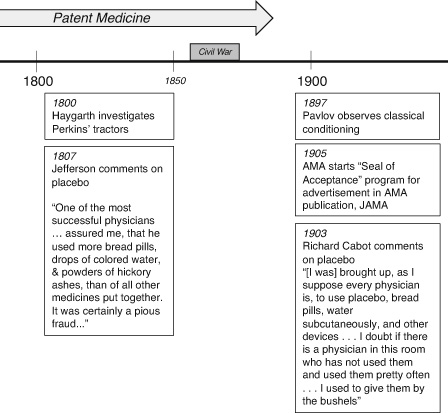

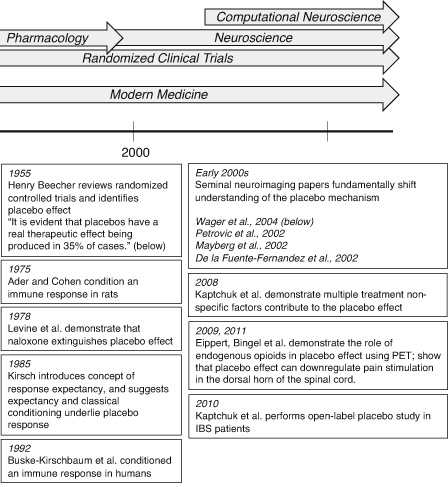

Figure 4 The timeline of research areas, medical approaches, and major events in the history of placebo effects.

Figure 4 (continued)

Figure 4 (continued)

Figure 4 (continued)

It has taken hundreds of people performing thousands of experiments with tens of thousands of patients to bring us to this moment (figure 4). In the chapters that follow, I will explore some of what we have learned about placebos over this time. Although it is abundantly clear that placebo effects are real neurological responses that elicit changes in our physiology, we have not traveled too far from where Haygarth left us on January 1, 1800. Placebo research still bears the stigma of quackery and deceit, making many a physician and scientist uncomfortable. In many respects, in the land of the living, placebos are still in mourning.