The opposing Scots armies that fought in the Civil War enjoyed a considerable degree of commonality. Both were largely comprised of pikemen and musketeers (overwhelmingly equipped with matchlocks) levied out in traditional fashion by their feudal superiors either at the behest of the King’s lieutenants or the Estates in Edinburgh. There were as a rule more Highland clansmen in the Royalist ranks than were levied out by the government, but it was rare for them to appear in appreciable numbers on either side. The popular image of Montrose leading an army of ferocious Highland warriors against a hapless band of Lowlanders served up for destruction in the name of the Covenant is a gross distortion of the actual, much more complex, picture.

The theory; a fully equipped musketeer as depicted by de Gehyn c.1603. Allowing for changes in fashion and the replacement of the large hat with a bonnet, most Scots regulars were kitted out as shown, although there is no evidence for the use of musket-rests.

The composition and character of the Royalist army was constantly evolving, but in broad terms it is possible to draw a fairly clear distinction between those troops who fought under Montrose during the first half of the campaign up to the winter battle of Inverlochy, and the army which fought at Auldearn and afterwards.

Prior to the fight at Inverlochy the greater part of the Royalist army was in fact made up of Irish mercenaries, originally recruited by Randal McDonnell, Earl of Antrim, and commanded in Scotland by a Hebridean exile named Alasdair MacColla. While formally organised in three regiments the brigade was, like most mercenary formations of the time, made up of individual companies of very diverse origins. Three of the companies were actually Hebridean Scots who formed MacColla’s Lifeguard, but the remainder were indeed Irish, chiefly recruited in Ulster but including officers and men drawn from as far apart as Connaught and Dublin and even, according to John Spalding, some veterans of the famed Spanish Army of Flanders. If the bards are to be believed, some of the Hebrideans certainly had broadswords but the majority of the rank and file dressed in breeches and trews and were variously equipped with matchlock muskets and short pikes in the usual manner. These regulars accounted for most of the Royalist infantry at Tibbermore and at Aberdeen two weeks later. After this, however, like all 17th-century regiments they gradually and inevitably succumbed to exhaustion, disease and desertion. They still formed a significant part of the Royalist army at Inverlochy but thereafter their importance waned. This was exacerbated as MacColla became steadily more involved in rallying the Western clans for a private war against the clan Campbell. By 1645 the remaining mercenary companies appear to have been re-organised into just two small battalions commanded by colonels Laghtnan and O’Cahan.

The reality; a Scots mercenary sketched by Köler in Stettin c.1631. The curious breeches may be intended to represent the normally close-fitting trews, but as equally close-fitting hose were still widely worn by German peasants it may be best to assume that the artist drew exactly what he saw.

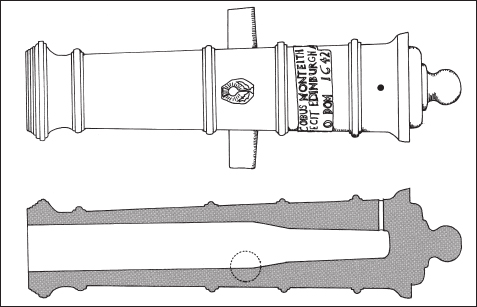

Artillery support for either side during the Civil War in Scotland was largely confined to light guns similar to this one cast in Edinburgh by James Monteith, although Baillie’s army at Kilsyth had a larger piece named ‘Prince Robert’ which had originally been captured at Marston Moor.

Happily for the Royalists, one of the principal results of the victory at Inverlochy on 2 February 1645 was the defection of a regular Covenanter cavalry regiment led by the Marquis of Huntly’s eldest son, Lord Gordon. He was also able to levy substantial numbers of good infantry from amongst his father’s people to replace the wastage amongst the Irish. At the same time he provided the Royalist army with the battle cavalry it needed to take on the veteran regiments being recalled from England. The quality of this cavalry was variable, ranging from Gordon’s own regulars to so-called ‘dragooners’ who were literally no more than foot soldiers sitting on ‘garrons’ or very small ponies. Nevertheless cavalry formed an increasingly significant element of the Royalist army and its successes in 1645 sometimes owed more to this arm than to the vaunted Highlanders. Most were armed with swords and pistols, although there is evidence that some were lancers.

The Highland contingents marching with the Royalist army fell into three broad and overlapping categories. First there were the casual marauders who attached themselves in the expectation of plunder and usually melted away if there was any serious danger of fighting. Secondly there were various contingents drawn out of the Western Clans whose first priority was the war with the Campbells and who therefore marched with the army merely as allies, chiefly at Inverlochy and Kilsyth, but otherwise pursued their own objectives. The best of the Highlanders, however, were the regiments raised in Perthshire by Patrick Graham of Inchbrackie and in Upper Deeside by Donald Farquharson of Monaltrie. It is unlikely that they could ever be described as well disciplined, but they became good (and ultimately well-equipped) veteran soldiers. Monaltrie’s men at least were described by one contemporary as a ‘standing regiment’ (i.e. regulars) and presumably included pikemen. Otherwise the clansmen who followed MacColla were pretty poorly armed. The men in the front rank generally had swords or axes, but those behind were only armed with dirks and bows. As a general rule of thumb, the smaller a Highland contingent the better armed.

Superficially, the Royalist army’s tactical doctrine appears deceptively simple. A case can be made for reducing it to simply marching up close to the enemy, firing a single volley and then launching a wild so-called ‘Highland’ charge. An argument has indeed been presented for crediting Alasdair MacColla with the ‘invention’ of these tactics, but in fact it was one commonly employed by many 17th-century armies – including the English Royalists at Naseby for one! However, as will become clear from the narrative, the battles were far more prolonged affairs than they might at first appear from the generally terse contemporary accounts. In fact the charge, far from being launched precipitately, was actually the culminating moment of a long and often inconclusive firefight. In the later battles it came more often than not after the Royalist cavalry had already moved against the flanks and rear of the enemy. Montrose’s standard tactical repertoire was very largely restricted to holding fast in the centre until both opposing flanks had been driven or beaten in, and then launching at all-out attack to finish the affair.

Udny Castle, Aberdeenshire. Orginally a Royalist, John Udny of that Ilk refused to join with Huntly in early 1644 and later led the Earl of Kinghorn’s Belhelvie tenants against Montrose at the Craibstane Rout.

Highland mercenary after Köler c.1631. This particular soldier seems to be wearing a belted plaid. The large butcher knife which appears to be his only weapon is almost certainly a crudely drawn dirk – most clansmen carried these rather than the larger and more expensive broadsword.

Coat and breeches recovered from a 17th-century corpse buried in a bog at Quintfall Hill in Sutherland. While coin evidence dated the presumed murder to the 1690s the style of the clothing – and particularly the stand-up collar – is much earlier. The buttons are balls of scrap cloth.

The Scots Army was a conscript force. In theory all those aged between the traditional ages of 16 and 60 were liable to turn out equipped with ‘arms defencible’ (hence their sometimes being designated ‘fencibles’) for up to 40 days’ service at their own expense. If they were retained in service for longer, central government assumed responsibility for looking after them. In practice a series of preliminary musters whittled them down to a manageable pool of young and unmarried men who were actually fit for service, and even then it was customary to accept only one man in four or even just one in eight. Therefore, while a large number of troops were sent into England in 1644, a very substantial reserve of manpower remained behind that could be called out and formed into regiments either as reinforcements or for internal security duties. By and large it was these so-called ‘second line’ troops, occasionally boosted by burgh militias, who faced the veteran Irish mercenaries in the early stages of the campaign and this simple qualitative difference is alone sufficient to account for the Royalists’ initial success. By 1645, however, not only did the survivors have a pretty good idea what they were doing, but the government had also recalled sufficient of its own veterans from England to take over from these levies. Consequently, although the Royalists continued to win battles, they faced a much harder job.

Few if any of the Scots infantry wore armour and they were generally equipped with either pikes or matchlock muskets, although towards the end of the war some men were kitted out with corselets and helmets and armed with halberds to take on Highland swordsmen. Ordinarily the cavalry similarly lacked armour although many had buff-coats and jacks. In general terms the cavalry relied upon their pistols and carbines rather than shock action, but significant numbers of them were armed with lances. Where possible it was customary to deploy regiments in two squadrons; one comprising men armed with pistols and the other of lancers. Independent troops, of which there were a number, were normally armed with pistols rather than lances.

Highland bowman by MacIan; bows were common enough both amongst Montrose’s forces and some of the northern levies who fought at Auldearn, but two-handed swords were rare.

Artillery was occasionally used but generally in sieges rather than in the field. By and large the difficulty of transporting guns in a country that lacked good roads, and consequently relied upon pack animals for the movement of goods, meant that only the lightest and least effective pieces could be deployed.