The day after the battle the rebels returned to Elgin, which they plundered thoroughly before falling back still further. Re-crossing the Spey, they rested for a few days at Birkenbog near Cullen, where they engaged in plundering and burning the Earl of Findlater’s lands. Meanwhile Baillie was on the move. Delayed by a fruitless raid into Atholl, he had resolved to re-unite his own forces with those sent north under Hurry and crossed the Dee near Birse only to receive unconfirmed reports of a battle on 11 May. At this point he had only 800 Foot and 100 Horse, the remainder of his army having been left behind to watch the passes. Not unnaturally he halted at Tarland to wait for reinforcements. These turned up a week later in the shape of the Earl of Balcarres at the head of his own veteran regiment of cavalry and two ad hoc battalions of ‘redcoats’. The latter, under the command of Colonel Robert Home, were drawn from the regiments of the Scots army in Ulster. Even with this solid reinforcement he was inclined to be wary since he lacked reliable intelligence of the rebels’ whereabouts. This was remedied when Sir John Hurry broke out of Inverness with his remaining cavalry on 20 May.

At that point the balance of affairs abruptly shifted. Not only did Baillie now know exactly where the rebels were, but for the first time he also learned that their curious and quite uncharacteristic inactivity proceeded from their heavy losses in the battle. Moreover, widely dispersed as they were, they were clearly vulnerable to a sudden offensive – and so it proved. On 21 May Montrose received ‘haistie advertesment’ that Baillie was marching north from Cocklarochie. His initial reaction was to move forward with whatever troops were immediately at hand. He began digging in at Strathbogie (Huntly) Castle that evening. However, later that night he decided discretion was, after all, the better part of valour and hastily decamped westwards to Balvenie on Speyside.

Tolquhon Castle near Udny in Aberdeenshire; Walter Forbes of Tolquhon was a prominent adherent of the Covenant, held the castle against Huntly’s men early in 1644 and afterwards fought in the Craibstane Rout at Aberdeen.

The ford over the river Don at Mountgarrie crossed by Baillie’s army in its advance to contact on the morning of 2 July 1645. The Royalist position on Gallows Hill is marked by the tree-crowned hill in the left distance.

Baillie was soon on the rebels’ trail and caught up with them at Glenlivet, showing his troops must have been marching hard. The rebels shook him off again at nightfall, however. Next morning Baillie’s scouts deduced by the trampled grass and heather that the rebel army was making for Abernethy on Speyside. Setting off again he seems to have caught up with them somewhere near Aviemore ‘in the entrie of Badzenoch, a very strait country, where, both for unaccessible rocks, woods, and the interposition of the river, it wes impossible for us to come at them’.

Reluctantly he had to admit defeat. His men had done all that was asked of them and more, but now they were exhausted and starving, the cavalry complaining that they had had no food for 48 hours. With the rebels posted in an unassailable position, Baillie had no alternative but to pull back to Inverness and refit.

As soon as Baillie had marched out of sight Montrose sought to capitalise on his isolation by lunging southwards, hoping to break out of the hills into the seemingly undefended Lowlands. Instead the rebels found themselves confronted by another force under the Earl of Crawford-Lindsay1, dug in along the river Isla at Newtyle in Angus. Whatever hopes Montrose might have entertained of forcing this position were then abruptly dashed by the news that Baillie had moved out of Inverness and was devastating the Gordon recruiting grounds in the north-east. Lord Gordon thereupon headed north with all his men, leaving Montrose with just 200-odd Irish mercenaries and no alternative but to retreat back into the hills.

Baillie meanwhile had crossed the Spey and rendezvoused with Crawford-Lindsay at Drum Castle near Aberdeen. The Earl brought bad news. The Committee of Estates was dissatisfied with his handling of operations and rather astonishingly considered him to be insufficiently determined in his pursuit of the rebels! Instead a new army was to be formed under the Marquis of Argyle and Baillie, now relegated to a purely defensive supporting role, was ordered to give up his own ‘Irish’ brigade (the 1,200 veterans drawn from the Scots army in Ulster under Colonel Robert Home) and 100 of Balcarres’ Horse in exchange for a mere 400 men of the Earl of Cassillis’s Regiment of Foot.

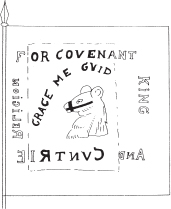

Only the central portion of this all-white colonel’s colour was captured at Dunbar or rather more likely at Inverkeithing. The surviving lettering is black, the uncoloured lettering being reconstructed. It was carried there by Forbes of Leslie, but the old Religion For Covenant King and Cuntrie motto indicates that it may originally have been carried by the regiment raised in Aberdeenshire by Lord Forbes in 1644. At least part of the regiment may have fought at Alford under Forbes of Leslie since Baillie picked up the surviving Aberdeenshire forces at Leslie Castle on the day before.

Alford: Gallows Hill as seen from Baillie’s position below. The top of the hill is now crowned with trees but the centre and left wing of the Royalist army appears to have been drawn up along the prominent but slightly lower ridge line clearly seen in this photograph.

This nonsensical plan was soon abandoned. First Argyle refused command of the new army and then Crawford-Lindsay went off with it on a pointless expedition into Atholl. Baillie meanwhile, far from remaining on the defensive, was ordered to take his badly depleted little army back into rebel territory and rendezvous with the Earl of Seaforth. Unfortunately, despite receiving a substantial shipment of muskets and pikes with which to equip his new levies, Seaforth failed to make the rendezvous on Speyside. General Baillie was falling back on Aberdeen when he ran into the rebels at Keith on 24 June. Fortunately, having had some warning of their approach he took up a good position by the church and the discomfited rebels were once again reduced to challenging him to come down and fight them in the open. Naturally enough he refused and to his surprise they immediately began retreating southwards. Intrigued he sent his scouts out again and discovered that the invitation to fight at Keith had been a bluff. Alasdair MacColla was absent with his men and the rebels were just as weak as he was. Setting off after them he came in sight of the rebels at the foot of the Coreen Hills, some distance to the north of Alford. There Montrose turned at bay on some rising ground either at the Suie Foot or Knockespock. Baillie declined to fight and ‘turned aside about three miles to the left’ to rendezvous with the Aberdeenshire forces at Leslie Castle. Greatly relieved, Montrose then hastily decamped down the Suie road to Alford.

The morning of 2 July 1645 found the rebel army posted on top of a large, rounded eminence known as Gallows Hill, just to the south of the swift-flowing river Don. That much is certain, but there is some considerable dispute as to where the battle was actually fought. The generally accepted version of events in secondary sources is that Baillie followed the Royalists down the Suie Road, crossed the Don at Boat of Forbes directly to the north of Gallows Hill and mistaking the rebel forces posted thereon for a rearguard, rashly tried to push past only to have them descend upon his men like the proverbial wolf on the fold.

Alford: The Royalist right wing was initially positioned along this sky-line before advancing down the gentle slope towards the camera.

According to a contemporary Aberdeenshire ballad (evidently written by one of the unfortunate Forbes levies), having spent the night at Leslie, Baillie in fact marched due south parallel to, but some distance to the east of, the Suie Road. Furthermore, far from rushing blindly in pursuit of the rebels, the ballad specifically relates that Baillie formed his men in order of battle at Mill Hill. This is a farm lying on the road that crosses the Correen Hills between Knock Soul and Satter Hill, near where it comes down to cross the Don by the ford at Mountgarrie. This ford lies about a mile downstream from Boat of Forbes and the fact that Baillie formed his men in order of battle before crossing at Mountgarrie confirms that he was deliberately advancing to contact, not from the north, but from the east. Nevertheless, recognising that the rebels held a strong position on top of the hill, once he was across Baillie halted on the low-lying How of Alford.

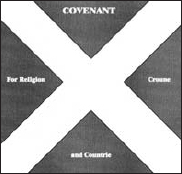

This colour was one of a number carried by Forbes of Leslie’s Regiment in 1650 although the archaic motto indicates it was originally used by Lord Forbes’ Regiment in 1644. It is green with a yellow saltire, gold lettering and a stag’s head depicted naturally.

Baillie’s army can be partially reconstructed both by reference to his own report and other official papers. He had at least six regiments of regulars – Cassillis’s, Elcho’s, Lanark’s, Moray’s, Glencairn’s and Callendar’s – of which the first at least mustered about 400 men. The probability is that in total he had about 2,400 infantry although it is possible that there may also have been a seventh regiment, made up of Aberdeenshire levies. Baillie himself reckoned that he was outnumbered by about 2:1 and rather unusually drew his men up only three ranks deep to avoid their being outflanked.

As to the cavalry protecting those flanks, Baillie makes reference only to Balcarres’ Regiment on the left and Halkett’s Regiment on the right totalling a mere 260 men. However the Royalist accounts, perhaps predictably, credit him with twice that number and it is probably significant that Baillie also refers to his regiments being drawn up in three squadrons rather than the two that was the normal practice in the Scots army. Presumably therefore the additional squadrons were some of the Aberdeenshire troops picked up at Leslie the day before and Baillie may therefore have had something approaching 400 cavalry in all.

Initial dispositions at the battle of Alford. The present village is largely a product of the railway age and in 1645 was represented only by a small scatter of cottages adjacent to Balcarres’ position. Both sides moved forward to meet in the centre of the field.

The composition of the rebel army is not quite so clear. Notwithstanding Baillie’s claim to have been outnumbered, there is fairly broad agreement that they disposed of some 200–300 cavalry commanded by Lord Gordon and his brother Aboyne, and something over 2,000 infantry.

According to Ruthven the main battle or centre comprised the Strathbogie Regiment and ‘Huntly’s Highlanders’ – a rather elastic term that certainly encompassed James Farquharson of Inverey’s ‘standing regiment’ as well as William Gordon of Monymore’s Strathavan men. In total the Gordon contingent must have been about 1,000 strong. To all intents and purposes it was made up of regulars, or at least veterans who could be relied upon to do what they were told by Inverey, who had the command of the whole. Oddly enough, however, Montrose’s chaplain, George Wishart, claimed that MacDonald of Glengarry commanded the centre. While Ruthven explicitly denied this statement, it does point to the surprising presence of a MacDonald contingent that may have added around another 200 to the front line.

Alford: The battlefield as seen from the centre of the Royalist start line. The flat and open nature of the How of Alford is readily apparent.

Since Baillie clearly had more cavalry than the Royalists, the remaining Irish mercenaries were parcelled out on the wings to support the rebel cavalry – Laghtnan’s Regiment with Lord Gordon on the right and O’Cahan’s with Aboyne on the left. In addition there was also a reserve placed behind the centre under the command of Lord Napier, although its composition is uncertain.

| ROYALISTS | |

| Strathbogie Regiment | 500 |

| Colonel James Farquharson of Inverey’s Regiment | 300 |

| Colonel William Gordon of Monymore’s Regiment | 200 |

| MacDonalds of Glengarry | 200 |

| Irish companies | 600 |

| Cavalry | |

| Lord Gordon’s Regiment | 200 |

| Viscount Aboyne’s Regiment | 300 |

| COVENANTERS | |

| Earl of Callendar’s Regiment | |

| Earl of Cassillis’ Regiment | |

| Lord Elcho’s Regiment | |

| Earl of Glencairn’s Regiment | |

| Earl of Lanark’s Regiment | |

| Earl of Moray’s Regiment | |

| Colonel George Forbes of Millbuie’s Regiment(?) | |

| Total: 2,400 | |

| Earl of Balcarres’ Horse Sir James Halkett’s Horse  |

260 |

| Sir William Forbes of Craigievar’s Horse John Forbes of Leslie’s Horse Master of Forbes’ Horse  |

120 |

Understandably enough, Baillie was far from keen on the idea of attacking and afterwards complained that he was ‘necessitate to buckle with the enemie’ despite his assessment that he was outnumbered. Just why he was ‘necessitate’ was not explained but there seems to have been a pretty widespread rumour that he was hustled into it by Balcarres’ forwardness. At any rate all the sources agree that the battle began with a clash between his men and Lord Gordon’s.

With the slope in their favour Lord Gordon’s men initially threw the Covenanters back, but then were in turn brought to a stand after Balcarres committed his second squadron. Baillie himself then tried to intervene by ordering Forbes of Craigievar’s squadron to charge the rebels in flank but instead Craigievar simply moved up behind Balcarres to add his weight to the press. In the end it was the intervention of Gordon’s supporting infantry which proved decisive. In just a few moments Balcarres’ formation fell apart and his troopers scattered in panic.

THE CAVALRY BATTLE AT ALFORD, 2 JULY 1645 (pages 74–75)

Alford is perhaps chiefly memorable for being the first of the Scots’ civil war battles in which there was a cavalry fight of any size – which eventually decided its outcome. On the Royalist left wing Viscount Aboyne’s regiment initially contented itself with an ineffectual exchange of carbine and pistol fire with Sir James Halkett’s men, but over on the right wing Lord Gordon’s regulars (1) came up very firmly against the two squadrons of the Earl of Balcarres’ Regiment (2) – who were hardened veterans of Marston Moor. Both sides advanced into contact, fired their pistols and commenced pushing. Locked knee to knee, heavy cavalry normally attempted to ride forward and ride down the opposing regiment, theoretically ‘in full career’ but in reality at a steady trot. Often enough, as in the case of Aboyne’s and Halkett’s men, they would simply come to a halt and blaze away at a safe distance. However, if both sides kept moving and met with equal resolution, the contest quite literally turned into a pushing match remarkably similar in principle to that engaged in by pikemen. Instead of fumbling to reload their pistols or slashing ineffectively with their swords – since in any case neither side could actually reach the other – they concentrated on trying to spur or otherwise urge their horses forward with the aim of bursting apart the locked ranks in front of them (3). At first neither side had the advantage at Alford since the slope at the foot of Gallows Hill was too gentle to provide much impetus to the Royalists, beyond compensating for the fact that they were outnumbered by Balcarres’ men. However, Balcarres’ reserve, a locally raised squadron commanded by Sir William Forbes of Craigievar, then entered the fight by moving up and quite literally adding their weight to the press (4). Lord Gordon had no corresponding cavalry reserve and for a time was in some danger of being pushed back, but Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Laghtnan then led forward his Irish mercenaries, ordering them to drop their pikes and muskets and fall on with their swords and dirks (5), as recalled by Gordon of Ruthven: ‘colonell Nathaniell Gordoune giueing him in charge to hogh (hamstring) there horses; for they ware so many, and so well mounted, as they still raly in on one parte or other, making so many new assayes as, notwithstanding all the waliant charges they receaued by the hunder horse, who could not [be] brokin, but still charged on all quarters where there was most dangeres; yet could they not be routted till colonell McLachlen fell to worke with there horses, where-of there ware not ten of twelfe lamed when they tooke them to flight.’ (Gerry Embleton)

Alford: The scene of the main battle. It was here where Baillie’s infantry ‘behaved themselves as became them’ until overwhelmed by sheer weight of numbers and the Royalist cavalry coming in on their rear.

The fighting on the other wing is rather more obscure, but the indications are that Halkett’s troopers never came into contact with Aboyne’s men at all. Instead both sides contented themselves with an ineffectual exchange of pistol and carbine fire until Lord Gordon, swinging right around the rear of Baillie’s infantry, broke in upon Halkett’s men from behind. Unfortunately, in the understandable confusion that followed Lord Gordon was killed – according to local tradition shot in the back by one of his own men, or more likely by one of Aboyne’s troopers.

It was the end too for Baillie’s infantry. Thus far they had held their own in a fire-fight with the rebels but, as he afterwards reported: ‘Our foot stood with myselfe and behaved themselves as became them, untill the enemies horse charged in our reare, and in front we were overcharged with their foot.’ George Wishart, Montrose’s chaplain, also stated that ‘they fought on doggedly, refusing quarter, and they were almost all of them cut down’. Substantial reinforcement drafts were certainly ordered for some of Baillie’s regiments shortly afterwards and the survivors grouped together in provisional units. Halkett’s Regiment for example was ‘broken’ and drafted into Balcarres’ Regiment. However, the contemporary ballad about the battle, which relates the misfortunes of the Aberdeenshire forces with quite refreshing candour – ‘They hunted us, and dunted us, and drove us here and there’ – only admits to 300 dead, which may be close to the true figure.

Rebel losses may also have been high. Fraser refers to ‘a considerable losse upon Montrosse his side’, while Ruthven speaks of seven officers killed besides Lord Gordon, suggesting a total of 80–100 dead.

At long last Montrose had a victory that he could exploit. There was still an army under Crawford-Lindsay to the south of him but he knew that after Auldearn, Seaforth and the northern levies would not stir beyond Inverness. With Baillie’s army also destroyed he was now able to move south with his rear secure. The need for Montrose to do something to relieve the pressure upon the King was greater than ever. The King’s field army had been badly beaten at Naseby in Northamptonshire a few weeks earlier.

Alford: The main cavalry battle was fought in this area, with the Royalists pushing from left to right. The Gordon Stone, supposedly marking the spot where Lord Gordon was killed, stands within an adjacent council depot.

Nevertheless it was a slow business. With his elder brother buried in Aberdeen with all due ceremony, Aboyne agreed to march south but first insisted on raising more men. In the meantime, however, he extracted a promise from Montrose that he would not commit to battle until reinforced. This rather suggests the Marquis’s colleagues were by now somewhat wary of his predilection for rushing into fights without adequate reconnaissance.

Unfortunately, he then proceeded to do just that. At Fordoun in the Mearns, MacColla rejoined him with 1,400 men of the western clans and 200 of Inchbrackie’s Athollmen. Encouraged by this substantial boost to his strength Montrose immediately attempted a raid on Perth. He was lucky to get away when Baillie, who had taken over Crawford-Lindsay’s army, came after him and chased the Royalists back into the hills. Less lucky were the rebel camp-followers caught by Baillie’s cavalry and massacred in Methven Woods.

Exasperated by his failure to catch the rebel soldiers and by what he regarded as constant political interference in military operations, Baillie then resigned as commander of the army. Only very reluctantly was he prevailed upon to serve out his notice until a replacement, Major-General Robert Monro, could be fetched home from Ireland. In the meantime Aboyne came south to rendezvous with Montrose at Dunkeld, bringing with him 400 cavalry and 800 good infantry to take part in the culminating act of the campaign.

As Montrose pushed south once more, Baillie dug in at Bridge of Earn only for the rebels to by-pass his fortified camp and head for the Mills of Forth on 11 August. Delayed first by a wayward infantry brigade that marched home to Fife without authority and then by a memorable falling out with his political masters, Baillie was slow in initiating a pursuit. He crossed Stirling Bridge on 14 August, however, and promptly had yet another acrimonious row with his superiors. By now it was clear that the rebels were heading towards Glasgow rather than Edinburgh and Baillie’s scouts reported them to be encamped near Kilsyth on a high meadow overlooking the road.

Kilsyth: By marching directly across country Baillie avoided the ambush which Montrose had prepared above the road. However, the ‘unpassable ground’ initially prevented him from exploiting the exposed Royalist flank.

Next morning, learning that the rebels had not moved on, it was decided to go after them. Very sensibly, however, Baillie left the road and ‘marched with the regiments through the corns and over the braes, untill the unpassible ground did hold us up. There I imbattled, where I doubt if on any quarter twenty men on a front could either have gone from us or attack us.’ This was unfortunate for he was actually sitting on the rebels’ left flank and so poised to inflict a memorable defeat. In the rather too confident expectation that Baillie’s army would blithely march straight down the road, Montrose had drawn up his men parallel to it on the high meadow. Baillie now had the opportunity to turn the tables on his would-be ambushers but found himself frustrated by the ‘unpassible’ ground. Although he afterwards stressed his misgivings about the move there was no real alternative but to continue the inadvertent turning movement by striking northwards and seizing the high ground at Auchinrivoch.

Highland mercenary in long coat sketched by Köler c.1631. Wearing the long tartan coat associated with clansmen from the north of Scotland he carries both musket and bow but like the others has only a dirk instead of a broadsword.

Initially the move went well enough. Many secondary sources deride it as having been foolishly carried out in full view of the Royalists but, as Baillie’s own very detailed account makes clear, his army was at this point in time concealed on a reverse slope. His men were therefore hidden long enough for them to get a clear start in what turned into a race for the high ground. Then everything went wrong.

Baillie had a total of some 3,500 infantry. The best of them belonged to his five regiments of regulars – Argyle’s2, Crawford-Lindsay’s, Robert Home’s, Lauderdale’s and ‘three that were joyned in one’. The latter, only some 300 strong comprised the remnants of Cassillis’s, Glencairn’s and the Lord Chancellor’s regiments. All were hardened veterans who had survived Alford or Auldearn. The remainder, however, were three newly levied regiments from Fife under the lairds of Fordell, Ferny and Cambo. All three regiments had earlier tried to disband themselves in the face of the Royalist offensive. Although they had been rounded up and fetched back again no one, understandably, had much confidence in them.

| ROYALISTS | |

| Strathbogie Regiment | 400 |

| Colonel James Farquharson of Inverey’s Regiment | 200 |

| Colonel William Gordon of Monymore’s Regiment | 200 |

| Irish companies | 500 |

| MacColla’s Lifeguard | 120 |

| Colonel Patrick Graham of Inchbrackie’s Regiment | 200 |

| Western Clans | 1,400 |

| Cavalry | |

| Viscount Aboyne’s Regiment | 300 |

| Colonel Nathaniel Gordon’s Regiment | 80 |

| Earl of Airlie’s Regiment | 80 |

| Dragooners | |

| Viscount Aboyne’s Regiment | 120 |

| Captain John Mortimer’s (Irish) Regiment | 100 |

| COVENANTERS | |

| Marquis of Argyle’s Regiment | 300 |

| Earl of Crawford-Lindsay’s Regiment | 400 |

| Colonel Robert Home’s Regiment | 1,000 |

| Earl of Lauderdale’s Regiment | 400 |

| Lieutenant-Colonel John Kennedy’s Battalion | 300 |

| (‘three … joyned in one’) | |

| Fife levies | |

| Colonel James Arnot of Ferny’s Regiment | 400 |

| Colonel John Henderson of Fordell’s Regiment | 400 |

| Sir Thomas Morton of Cambo’s Regiment | 400 |

| Cavalry | |

| Earl of Balcarres’ Regiment | 3003 |

| Colonel Harie Barclay’s Regiment | 60 |

Baillie intended that his march should be screened by a composite battalion of musketeers drawn from the ranks of his regular regiments. When they broke cover a short distance to the north of the start line, however, they were spotted immediately by the rebels. At that point, to Baillie’s horror, the battalion’s commander, Major John Haldane, decided that he could best carry out the spirit of his instructions by establishing himself in the farm at Auchinvalley. A rebel officer named Ewen Maclean of Treshnish immediately accepted the challenge. A spirited skirmish began around the farm enclosures and, despite Baillie’s repeated orders to disengage, it soon began to escalate in intensity as MacDonald of Glengarry led up his men to reinforce Treshnish.

Kilsyth: Baillie’s attempt to manoeuvre on to the Royalists’ flank degenerated into a confused encounter battle as both sides hurried all available units into the enclosures around Auchinvalley.

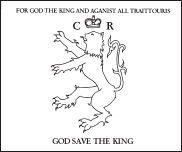

The Strathbogie Regiment: John Spalding noted that on 15 April 1644 the Marquis of Huntly ‘causit mak sum ensignes, quhair on ilk syde wes drawin ane red rampand Lion, haueing ane croun of gold above his heid, and C.R. for Carolus Rex, having this motto, FOR GOD, THE KING, AND AGAINST ALL TRAIT-TOURIS, and beneth, GOD SAVE THE KING.’ The ground colour is not given, but it should logically have been yellow. Although Huntly’s forces had to be temporarily disbanded shortly afterwards, the Strathbogie Regiment and its distinctive colours became a familiar sight on Scotland’s battlefields.

Recognising that, for good or ill, he had been drawn into an engagement, Baillie rode to the front with his cavalry commander, the Earl of Balcarres. In his later evidence Baillie provided both a unique insight into the sequence and nature of the orders given and a flavour of the confusion and excitement as his army, far from being helplessly swept away as it was strung out on the line of march, moved resolutely into the attack.

‘He [Balcarres] asked me what he should do? I desired him to draw up his regiment on the right hand of the Earl of Lauderdale’s. I gave order to Lauderdale’s both by myselfe and my adjutant, to face to the right hand, and to march to the foot of the hill, then to face as they were; to Hume to follow their steps, halt when they halted, and keep distance and front with them. The Marquess [of Argyle] his Major, as I went toward him asked what he should doe? I told him, he should draw up on Hume’s left hand, as he had done before. I had not ridden farr from him, when looking back, I find Hume had left the way I put him in, and wes gone at a trott, right west, in among the dykes and toward the enemy.’

First Baillie’s attempt to seize the Auchinrivoch position had been sidetracked by the untimely initiative of one subordinate, now another was compounding the error by rushing to his support. Most secondary sources assume that MacColla’s Highlanders overran Haldane’s musketeers and then swept on to attack the rest of Baillie’s army as it was strung out on the line of march. Instead, as Baillie’s detailed account all-too vividly makes clear, command and control on both sides was rapidly breaking down as the two armies rushed piecemeal into an encounter battle that neither had intended.

Highland bowman wearing a yellow battle-shirt or leine. Whilst the very wide sleeves appear unconvincing they do in fact appear in contemporary illustrations. The Irish influences clearly point to his coming from one of the western clans.

‘I followed [Home] alse fast as I could ride,’ continued Baillie; ‘and meeting the Adjutant on the way, desired him he should bring up the Earl of Crafurd’s regiment to Lauderdale’s left hand, and cause the Generall-Major [John] Leslie draw up the regiments of Fyfe in reserve as of before; but before I could come to Hume, he and the other two regiments, to wit, the Marquess of Argyles and the three that were joyned in one, had taken in an enclosure, from whilk (the enemy being so neer) it wes impossible to bring them off.’

Instead of straggling along in a column, his army was now drawn up in three distinct bodies. Under his personal command up amongst the stone or turf-walled enclosures by Auchinvalley were some 1,600 regulars. Behind Baillie and to his right were a further 800 infantry under Major-General Holbourne and Balcarres’ 300 cavalry while somewhere to his left rear were the three rather shaky Fifeshire regiments under Major-General Leslie.

Facing them were just 1,600 or so Highlanders under MacColla, pinned down for the moment on the far side of the Auchinvalley enclosures: ‘The rebels foot, by this time, were approached the next dyke, on whom our musqueteers made more fire than I could have wished; and therefore I did what I could, with the assistance of such of the officers as were known unto me, to make them spare their shott till the enemy should be at a nearer distance, and to keep up the musqueteers with their pickes and collors, but to no great purpose.’

Nevertheless, with the Highlanders thus halted all was going to depend on what happened further to the north on what had now become Baillie’s right wing. Alexander Lindsay, Earl of Balcarres, was a competent and determined officer and now he did his best to hook around into the Royalist rear. At first all that stood in his path was a small troop of cavalry commanded by a ‘Captain Adjutant’ Gordon. Undaunted by the odds, the Royalists immediately charged and briefly checked Balcarres’ advance before the imbalance in numbers told against them. Just as they were on the point of being surrounded, however, Viscount Aboyne came to their aid with his personal lifeguard.

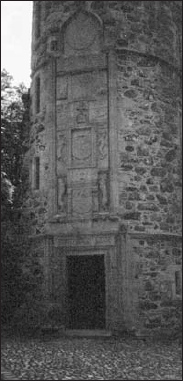

The remains of a civil war ravelin erected to cover the unfinished eastern wall of the Marquis of Huntly’s castle at Strathbogie. It is just possible that it may have been thrown up by Montrose’s forces while digging in there on the evening of 21 May 1645 but, on balance, it is unlikely that they would have had sufficient time.

A good study by Köler of a Highland bowman wearing his belted plaid as a cloak, wrapped up over his shoulders. Note also the ubiquitous dirk by his side instead of a broadsword.

It was obviously an adventurous ride for sheering away from Harie Barclay’s as yet unengaged lancers, the Royalists collided momentarily with the pikemen of Home’s ‘reid’ regiment. They were fired on by Home’s flanking musketeers before finally reaching Gordon’s beleaguered troop. Unsurprisingly, by then they were in pretty poor shape and Balcarres drove them back and up on to the high ground behind Montrose’s original battle-line. There at last the Covenanters were halted when Nathaniel Gordon and the Earl of Airlie counter-attacked with the main body of the Royalist cavalry. Ominously the area is still marked on modern maps as ‘Slaughter Howe’. Tired and badly outnumbered, Balcarres and his men were tumbled back down the hill again and out of the fight. Worse still, the victorious Royalist troopers then turned on the now-exposed right flank of Baillie’s infantry and so provided the opportunity for MacColla and his Highlanders to mount another frontal attack.

Once again, Baillie himself provided the most vivid account of what followed, relating that ‘In the end the rebells leapt over the dyke, and with downe heads fell on and broke these regiments ... The present officers whom I remember were Home, his Lieutenant Colonel and Major of the Marquess’s regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Campbell, and Major Menzies, Glencairne’s sergeant Major, and Cassillis’s Lieutenant Colonel with sundry others who behaved themselves well, and whom I saw none carefull to save themselves before the routing of the regiments. Thereafter I rode to the brae, where I found Generall Major Hollburne alone, who shew me a squadron of the rebells horsemen, who had gone by and charged the horsemen with Lieutenant-Colonell Murray and, as I supposed, did afterward rowt the Earle of Crawfurd, and these with him.’

With his front line overwhelmed by the rebel infantry, and Crawford-Lindsay’s and Lauderdale’s regiments dispersed by the rebel cavalry, Baillie and Holbourne ‘galloped through the inclosures to have found the reserve; bot before we could come at them, they were in flight’.

‘Jocke’; apparently the only contemporary illustration of a Lowland Scots infantryman, with characteristic large blue bonnet, short coat open breeches. Some Royalist accounts of Auldearn mention ‘helmeted men’ but otherwise pikemen were unarmoured.

Although there are no contemporary accounts of this particular episode, Baillie indirectly refers to some kind of a fight when replying to accusations that his men were so ill-prepared that they had not time to light the slow-match for their muskets before the rebels attacked: ‘The fire given by the first five regiments will sufficiently answer what concerns them: and for the other three (the Fife levies), I humbly intreat your Honours to inform yourselves of Generall-Major Leslie, the adjutant, and the chief officers of these severall regiments: if they doe not satisfie yow therein, then I shall answer for myself.’

With the rebel cavalry all engaged on the northern side of the battlefield and MacColla’s Highlanders fully occupied in dealing with Baillie’s regulars, it must have been the Gordon foot under Farquharson of Inverey and Laghtnan and O’Cahan’s Irish mercenaries who routed Leslie’s Fife brigade. It was all over very quickly and the whole army completely disintegrated. Baillie and some of his officers tried to rally the fugitives at ‘the brook’, presumably where the road crosses a stream at Auchincloch about 1¼ miles east of the battlefield, ‘bot all in vaine’. Instead, therefore, Baillie and Holburne made their way up to Stirling where they were eventually joined by the cavalry, who were badly shaken but otherwise largely unscathed.

Baillie’s regular infantry units must have held together fairly well in the retreat and were consequently left well alone. Even the ‘three that were joyned in one’ survived to be individually filled out again with new recruits and sent into England, but it was a very different story with the three Fife regiments. Dissolving into a panic-stricken rabble they were pursued for miles by the exultant clansmen and hundreds ruthlessly cut down. Indeed, it was said that for years afterwards dozens of boats rotted at their moorings in the little ports along the Fife coast, their crews dead at Kilsyth. In the longer term the slaughter also contributed to the myth of Highland savagery and so, in turn, paved the way for the later victories over other Scots soldiers at Killiecrankie and Prestonpans.

The magnificent (and unique) heraldic entablature above the door to Huntly Castle. The upper panels, held to have Catholic connotations, were defaced by Captain James Wallace of Monro’s Regiment during the Covenanters’ occupation of the castle in 1640.

Rebel casualties are unknown, but as they remained on the battlefield for another two days it can safely be surmised that they too had suffered heavy losses in what all the contemporary accounts agree had been very heavy fighting. Be that as it may, notwithstanding the beating they had just dealt out, they showed no inclination whatever to follow what remained of Baillie’s army to Stirling. Instead, just as after every other victory, Montrose chose to move off in a diametrically opposite direction. Somewhere to the south of him there was another contingent of Covenanters under the Earl of Lanark. Opinion is divided as to whether Baillie knew they were close at hand when he fought at Kilsyth. While he never suggested that disaster could have been averted by joining with Lanark first, his immediate impulse after rallying the army at Stirling was to march south and rendezvous with the Earl in Clydesdale. Unfortunately his cavalry were so demoralised that they flatly refused. Oddly enough, although Lanark himself fled to Berwick on hearing the news of the battle, at least one of his regiments remained in the field. Led by a tough professional named Sir John Browne, they harassed the rebels sufficiently for Sir John to be awarded £100 sterling ‘In thankful remembrance of good service with his dragoons against the rebels since 15th August last.’

Just what that service was does not appear but he no doubt did his best to curb the rebels’ descent into banditry. Glasgow was taken without opposition, but the clans were disappointed by Montrose’s refusal to let them sack the city. Nor did the ‘storm-money’ promised in lieu materialise and when Montrose, anxious to remove his men from temptation, withdrew to a camp at Bothwell they took to marauding instead and deserted in droves. There was perhaps some justification for a cavalry raid on Edinburgh mounted by Nathaniel Gordon, but little for a much larger raid on Kilmarnock and the towns along the Ayrshire coast led by MacColla. On 2 or 3 September MacColla left for good, taking all the remaining Highlanders with him, on his ultimately doomed attempt to re-establish MacDonald hegemony in the Isles.

This blue colour with a white saltire was captured at Dunbar, but the archaic wording of the inscription indicates that it probably belonged to Campbell of Lawers’ Regiment.

With his army melting away around him as never before, Montrose bestirred himself into marching on Edinburgh. After only the first day, however, Aboyne took his Gordons north, leaving Montrose with barely 500 Irish infantry and not much more than 100 cavalry. At this point Montrose should also have re-crossed the Forth, but instead seems to have decided that he must try to join the King in England at all costs, and so continued on his way to Edinburgh.

He never reached the capital. Learning that the plague – almost certainly typhus brought back by the army from the camps in England – was raging there, he instead turned south at Dalkeith, hoping to raise large numbers of cavalry in the borders. At first the signs were promising. The Marquis of Douglas joined him at Galashiels on 7 September with around 1,000 moss-troopers, but neither the Earl of Home nor the Earl of Roxburgh appeared at Kelso the next day. By 10 September he was at Jedburgh, poised to move south into England, when disturbing news reached him. Lieutenant-General David Leslie had passed through Berwick on 6 September with at least four regiments of infantry and six regiments of cavalry.

This gentleman is probably not a Highlander but a laird from North-East Scotland, wearing a combination of low-country and Highland clothes. He would be equally at home on foot or horseback, speaking Gaelic or Scots.

Abandoning for the moment any thought of crossing the border, the rebels headed west, probably with the idea of evading Leslie and regaining the hills by way of Clydesdale. On the afternoon of 12 September they reached Selkirk and while Montrose and all too many of his officers found comfortable quarters in the burgh, the greater number of the cavalry camped just to the west on the flat expanse of Philiphaugh and the infantry bivouacked in a nearby wood. As usual they were camping ‘commodiously’, which was unfortunate for unbeknown to them Leslie was approaching fast.

Intent on saving Edinburgh, Leslie had been hastening along the coast road (now the A1), but at the tiny village of Gladsmuir on 11 September he received word that the rebels were in fact lurking somewhere to the south of him. At least a part of Lord Coupar’s Regiment of Foot may already have been mounted and taking them along with his own cavalry, and two other regiments that joined him at Gladsmuir, he immediately set off in pursuit, leaving the rest of his infantry trailing behind.

The following night he ran into a rebel outpost in the village of Sunderland a little way to the north of Selkirk. Quite unsuspecting, the Royalists were literally caught napping and after a short, sharp fight only the commander, Charteris of Amisfield, and two or three of his men got away. In itself this was bad enough but, quite incredibly, when they reached Selkirk they were assumed to have been involved in a drunken brawl. Amisfield’s report that they had been attacked by Leslie’s men was dismissed out of hand and no attempt was made to rouse the army. Undisturbed therefore, Leslie and his men appear to have spent the rest of the night in the valley of the Tweed between Linglie Hill and Meigle Hill, just a little upstream from Sunderland.

Having left the majority of his infantry behind, Leslie had just over six cavalry regiments – his own, the Earl of Leven’s, John Middleton’s, Lord Kirkcudbright’s, Lord Montgomery’s and the Earl of Dalhousie’s – together with 40 troopers of Colonel Harie Barclay’s Regiment (the latter two units joined him at Gladsmuir). According to pay warrants these totalled some 3,000 men. In addition, he also had some 400 men of Colonel Hugh Fraser’s Dragoons – reputedly one of the best units in the Scots army – and as many as 700 of Lord Coupar’s Regiment of Foot, though it is perhaps questionable whether he had been able to find enough nags to mount all of them.

Ironically, the following morning dawned grey and misty and, had any notice been taken of Amisfield’s warning, the rebels might have been able to escape under cover of the fog. Instead they spent a lazy morning waiting for it to clear while all the time Leslie and his troopers were closing in. Legend has it that Montrose was still at breakfast when his scoutmaster, Captain Blackadder, crashed through the door ‘in a great fright’ to announce that Leslie was at hand, but Leslie’s official report unequivocally states that he attacked at 10.00am.

Be that as it may, Montrose flung himself on to the first horse he could catch and galloped across to Philiphaugh where he found ‘all in uproar and confusion’. The large body of cavalry encamped there was not only untrained and inexperienced but most of their officers, like Montrose, had taken themselves off to find beds in Selkirk the night before. Consequently the troopers were now scattered all over the haugh in loose bodies and making no attempt to form a battle-line. Even the veteran Irish, recognising perhaps that the battle was already lost, were in some disorder with a great many of them intent only on saving their own baggage.

The result was that Laghtnan and O’Cahan could only bring up about 200 infantry, less than half their number. At least, ‘According to their usual manner they had made choice of a most advantageous ground wherein they had entrenched themselves, having upon one hand an impassable ditch and on the other dikes and hedges, and where these were not strong enough they further fortified them by casting up ditches and lined their hedges with musketeers.’

From this description it would appear that the Irish were drawn up facing north with their left flank anchored on the Philhope Burn, their front covered by agricultural walls and ditches and the gap between their right flank and the river Ettrick held by the small body of veteran cavalry under Nathaniel Gordon and Lord Ogilvy.

This blue cavalry cornet with gold lettering, captured at Dunbar, bears the motto of the Forbes family and may have been carried by one of the Aberdeenshire units which fought against Montrose.

With a very comfortable superiority in numbers, Leslie divided his army in two at the Linglie Burn about ½ mile north of Selkirk. One wing, led by Lieutenant-Colonel James Agnew of Lord Kirkcudbright’s Regiment, crossed the River Ettrick and cleared Selkirk itself, capturing or chasing off those officers who had not been as quick off the mark as Montrose. The remainder of Leslie’s men, according to a reliable local ballad tradition, swung around the base of Linglie Hill and went straight at the rebels.

In a vain attempt to delay this advance Nathaniel Gordon led his troopers forward and engaged Leslie’s skirmishers in an exchange of carbine and pistol fire, but badly outnumbered they were driven in within a quarter of an hour. To cover their retreat either Laghtnan or O’Cahan led forward a body of musketeers. This in itself is sufficient indication of how desperate the situation was becoming. Almost at once, however, they were ‘forced by ours to retreat in great disorder’, presumably by Lord Coupar’s now dismounted infantry.

| ROYALISTS | |

| Irish companies | 500 |

| Cavalry | |

| Colonel Nathaniel Gordon’s Regiment | 60 |

| Earl of Airlie’s Regiment | 60 |

| Marquis of Douglas’s levies | 1,000 |

| COVENANTERS4 | |

| Earl of Leven’s Horse | 550 |

| David Leslie’s Horse | 550 |

| John Middleton’s Horse | 400 |

| Lord Kirkcudbright’s Horse | 600 |

| Lord Montgomery’s Horse | 470 |

| Harie Barclay’s Horse | 40 |

| Earl of Dalhousie’s Horse | 330 |

| Hugh Fraser’s Dragoons | 400 |

| Lord Coupar’s Foot | 700 |

James Graham, Marquis of Montrose as depicted in the frontispiece to the first (1647) edition of the very influential biography penned by his personal chaplain.

After these preliminaries there then seems to have been a pause before the battle began in earnest, perhaps because Leslie was still trying to develop the rebel position in the fog. The front between the enclosures occupied by the rebel infantry and the River Ettrick was relatively narrow. When Leslie moved forward again he could, therefore, send forward only one regiment at a time. His first attack was repulsed but when the rebels counter-charged for a second time they found themselves cut off and tried to escape northwards. By this time it was about noon. Montrose and his cavalry commander, the Earl of Crawford, had succeeded in patching together a second line with the border levies. Leslie ignored them, however, and instead wheeled to his right and ‘charging very desperately upon the head of his own regiment, broke the body of the enemy’s Foot, after which they all went in confusion and disorder’. Matters were not helped when Lieutenant-Colonel Agnew, having cleared Selkirk, crossed the Ettrick and attacked the remaining rebel cavalry who fled in all directions without putting up a fight.

This rather macabre black colour was made for Montrose in Holland or Denmark and carried by his mercenary infantry at the battle of Carbisdale in 1650. The severed head, dripping blood, is that of King Charles, copied here from a contemporary woodcut.

Amidst the confusion, Montrose’s adjutant, Stewart, managed to rally about 100 of the Irish at Philiphaugh Farm but surrendered after a vicious little fight that left half of them dead. With that the battle ended, but not the killing. Coldly announcing that quarter had only been promised to Stewart, O’Cahan and Laghtnan, Leslie proceeded to have all his prisoners shot. The numerous camp followers were also murdered, either then or over the next few days, but otherwise the rebels escaped surprisingly lightly.

Most of the cavalry escaped simply because they were able to run away faster, especially since most of them were local men, but at least half of the Irish infantry also got away. According to Wishart, 250 of them rejoined Montrose afterwards, probably at Peebles where he spent the night. Next day he crossed the Clyde, picking up some 200 Horse at the ford, and then swung north across the Forth and the Earn, taking refuge in Atholl by 19 September.

Having won a neat little victory, Leslie displayed little interest in pursuing the rebels and instead retraced his steps northwards to Haddington and then to Edinburgh. His seeming complacency was justified by events. Judged purely in material terms the rebels had escaped comparatively lightly from the fight at Philiphaugh. True, Montrose lost a couple of hundred of his veteran Irish mercenaries, but Leslie’s main achievement was in preventing him from recruiting a fresh army in the borders to replace the Gordons. The importance of this achievement was underlined in the months that followed.

At Dunkeld Montrose was rejoined by Inchbrackie but appeals to MacColla went unanswered and so he marched northwards with some 800 infantry and 200 cavalry to try to link up with the Gordons again. Instead he found himself in the middle of a local civil war that had little to do with national politics and everything to do with deep-seated family rivalries.

Returning home after Kilsyth, Aboyne had quite fortuitously surprised and captured the entire Committee of War for the north-eastern sheriffdoms and then followed this up by installing William Gordon of Arradoul as governor of Aberdeen and demanding that the burgh militia be mobilised as a garrison. Unsurprisingly this led to Major-General John Middleton being sent north with 800 men of his own and Lord Montgomery’s Regiments and he re-occupied the burgh at the end of the month. Although Middleton was understandably wary of venturing further with his little brigade, his presence provided sufficient impetus for a revival of pro-Government activity in Aberdeenshire under the Master of Forbes.

It was against this unpromising background that Montrose re-appeared and persuaded Aboyne to meet him at Drumminor Castle with some 1,500 infantry and as much as 500 cavalry under his wild younger brother, Lord Lewis Gordon. However, the Marquis ‘fynding himselfe now stronge eneugh to giue his enemies a day’ (i.e. strong enough to give battle), announced that he intended to march south again rather than confront Middleton, who by then was lying at Turriff. Aboyne very reluctantly agreed but then Montrose rather tactlessly put Lord Lewis Gordon under the command of the Earl of Crawford. Viewed objectively the appointment of Crawford, an experienced professional soldier, to lead the Royalist cavalry was a sensible enough move. Lord Lewis Gordon not only refused to acknowledge his authority, however, but proceeded to assert his independence by undertaking an unauthorised raid on one of Middleton’s outposts at Kintore.

The raid was spectacularly successful. Middleton’s men, considerably outnumbered, fell back to Turriff in such a panic that Middleton in turn fled northwards to Banff. There he was uncomfortably close to Strathbogie and this was sufficient excuse for Lord Lewis Gordon to return there. This in turn left Montrose with insufficient cavalry support for his proposed march southwards and so he reluctantly turned back to Alford where Aboyne also left him and returned to Strathbogie. Left with just Inchbrackie’s men and the last remaining Irish mercenaries, he moved over the mountains to Dunkeld and then, with the aid of a few recruits levied by Robertson of Inver, he tried to threaten Glasgow. This move was aimed at least in part at saving the lives of the Royalist officers captured at Philiphaugh. However, Leslie’s cavalry successfully kept him in the hills, O’Cahan, Laghtnan and Nathaniel Gordon were all hanged and, at the end of October, Montrose at last admitted defeat and trailed northwards to make his peace with the Marquis of Huntly.

Since the collapse of his own uprising in April of the previous year, Huntly had been in hiding in Strathnavar in the far north of Scotland. Now he was back and, while he was willing to put old differences aside for the present and work with Montrose, he made it very plain that he would do so as an ally rather than a subordinate. Moreover it also soon became clear that he regarded himself as the senior partner. He was operating on his own turf, by far the greater number of the Royalist troops owed him their personal allegiance and, in any case, Montrose was widely regarded as far too reckless and perhaps even more than a little unstable. This was the real legacy of Philiphaugh.

Ironically, Montrose had raised the rebellion in the first place to relieve pressure on his beleaguered King. The crushing Parliamentarian victory at Naseby in June, which had first drawn him south and then led him to undertake the disastrous march into the borders, now meant that sufficient Scots regulars could at last be released to deal with him. As winter approached, Glasgow was heavily garrisoned and fortified, and a strong line of outposts established along the Forth crossings. Dalhousie’s Regiment was based on Stirling while Lord Montgomery’s and Colonel Hugh Fraser’s Dragoons lay in Clackmannanshire. Lord Kirkcudbright’s Regiment was pushed forward to re-occupy Baillie’s old fortified camp at Bridge of Earn, from where contact could be maintained with both the Dundee garrison and with the Earl of Moray’s Foot, who were watching the Highland passes out of Atholl.

A splendidly anachronistic yet evocative study of a Highland swordsman by MacIan.

Further north, however, only Inverness was still in the Government’s hands and so, at the beginning of January 1646, Colonel Harie Barclay arrived in Aberdeen with his own regiments of horse and dragoons, Colonel Robert Montgomery’s Horse and two regular infantry regiments that had come north with Leslie – Colonel William Stewart’s and Viscount Kenmure’s. There they halted until the spring, while the battered but indefatigable Aberdeenshire levies were re-organised into a regiment of horse under the Master of Forbes and a regiment of foot under Colonel George Forbes of Mill Buie.

This important work was carried out without any interference since the greater part of the remaining Royalists were now on the far side of the river Spey. There Montrose was vainly trying to raise a new army while the Gordons engaged in a petty round of raid and counter-raid against their neighbours. Only the Earl of Crawford, based at Banff, presented any threat to the growing concentration at Aberdeen. At first he made life distinctly uncomfortable for Barclay with a series of raids pushed down Deeside by Farquharson of Inverey and from Fyvie Castle by Captain Blackadder. Eventually Barclay decided enough was enough and riposted with an even heavier raid on Banff that sent the rebels tumbling back across the Spey.

By the end of April relations between the Royalist commanders had deteriorated to the extent that Huntly and Montrose were operating independently of each other. Montrose embarked on a futile siege of Inverness. It was also reckless as Major-General John Middleton had come north to supersede Barclay and was then lying at Banff with a cavalry brigade and Mill Buie’s Foot. Huntly, on the other hand, having allowed his infantry to winter at home, had not yet concentrated his forces and was unable to cover the siege when Middleton suddenly lunged forward with his cavalry. Wishart subsequently accused the Gordons of treachery and alleged that Montrose’s rearguard, two troops of Irish dragooners commanded by captains Mortimer and McDonnell, were purposely decoyed away by Lord Lewis Gordon. Ruthven, on the other hand, explicitly denies the charge and accuses them of being negligent, which is altogether more convincing.

Whatever the truth of the matter, Middleton suddenly crossed the Spey, pausing only long enough at Elgin to feed and water his horses before pushing straight on through the night to Inverness. Having marched no fewer than 45 miles with no more than this single halt he took the Royalists completely by surprise. Alerted only by Middleton’s trumpets, Montrose’s men abandoned their guns and fled westwards without attempting to fight. Had they done so, Middleton might well have been defeated as both men and horses must have been utterly exhausted, but the deliberately sounded trumpet blast was enough.

With that the campaign was all but over. After clinging on for a few days Montrose swung to the south and took refuge in Speyside while Huntly, displaying unwonted energy, struck south and stormed Aberdeen on 14 May 1646. ‘It was thought’ said one chronicler, ‘to be one of the hottest pieces of service that happened since this unnatural war began, both in regard to the eagerness of the pursuers and valour of the defenders.’ It was also seven years to the day since the civil wars had begun with the Gordons’ victory over the Covenanters at Turriff in 1639. Three weeks later it was officially all over when word arrived from the King ordering the last of his forces to lay down their arms.

After protracted negotiations, Montrose accordingly surrendered to Middleton at Rattray near Blairgowrie on 30 July and then fled abroad. After four years he would return again, with a motley army of exiles and mercenaries, only to be ambushed at Carbisdale on 27 April 1650 and hanged in Edinburgh a month later. Ironically enough, hanged with him was Sir John Hurry who had fought against him at Auldearn, only to change sides and lead the Royalist cavalry at Carbisdale.

1 Originally simply known as John, Earl of Lindsay, he became the Earl of Crawford-Lindsay after the attainder of a Royalist officer, Ludovick Lindsay, Earl of Crawford. Confusingly the latter was still alive and well at the time and subsequently served under Montrose against Crawford-Lindsay.

2 This was a regular regiment, raised in the lowlands, which had been garrisoning Berwick-upon-Tweed. It should not be confused with Argyle’s Highland Regiment that fought at Inverlochy.

3 Balcarres’ Regiment was actually stronger than it had been at Alford as a squadron that had been detached with the Earl of Crawford-Lindsay’s independent force subsequently rejoined the regiment. Balcarres also absorbed the remnants of Sir James Halkett’s Regiment.

4 For once the numbers in each regiment can be established with reasonable precision since a grateful Government awarded a bounty to all those who fought at Philiphaugh.