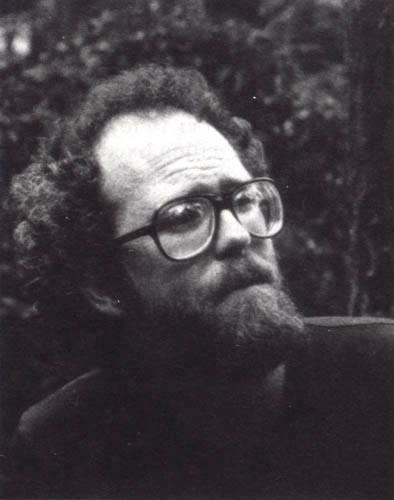

© Elyse Arnow

GRAHAM EVERETT

My primal landscape, like the island’s, is a topographical mix. There’s the snap and crash of a tough oak broken across a hurricane-torn road, its sandy berm a signature. How frozen potatoes popped under our boots as we winter-trekked over countless furrows to the woods hunting rabbit and deer. How once inside these woods the light shone in cathedral-like shafts. Younger, we learned about our bodies in other woods—the far side of huge rows of blueberry bushes behind bulldozed oak and bramble. We danced naked on that palatial earth.

I recall a pasture, rye-green rolling where sheep once grazed. A ram lurked in centerfield of a 1957 summer baseball game, ready to butt our butts. Sheep-dung, sun-dried and kicked into heaps, marked the bases.

Later, having moved further east, we did sneak into the chicken house and left eggshells hollow in the hens’ nests. Our poachers’ jars filled with scrambled yolk and white. More than once we stood wide-eyed before a bull and cow rutting in a dawn-lit barn, our nostrils filled with pungent dampness.

Another farmer, living closer to town, raised pigs. The spring squeal of baby pigs getting fixed went on a day and a night. Once, a bunch of castrated piglets died. They weren’t properly sulphured, or carefully cauterized. A crying I think I can still hear.

As this landscape finishes vanishing, singularities keep occurring. A pond persists where a road was built, slowing traffic each time it rains. How on foggy nights the old houses dream themselves filled again with light and laughter …

Today, we have the landscape of the new island. The spots of beauty—small and easily missed—hold on, sure of something progress can not guarantee. I continue to mine these spots, the ground under our feet, treading these neighborhood sidewalks, the lost paths of this island’s morained hills, as best as I can.