A Brief History of Magical Books, Words, and Symbols

The evolution of human expression—from pictures, to symbols, to alphabets, to words, and eventually to books and beyond—is a long and complicated one. What’s presented in this chapter only scratches the surface of a very rich history. The following are just some of the highlights, and ones that might especially be of interest to modern Witches.

Some of the material in this chapter includes linear history (we go from point A to point B a few times), but many of the sections here simply highlight especially interesting and influential moments in the history of the written word. The power of words and symbols to express complex ideas makes them magickal, even when they are being used for mundane purposes. Simply looking at a piece of art or even just a written (or typed) word can awaken all sorts of feelings and emotions, and has for tens of thousands of years.

The Cave Painters

Human beings have communicated through images for nearly 40,000 years. The first definitive examples of human art come from Western Europe (in what is now Northern Spain and Southern France) and the Indonesian island of Sulawesi.2 Both locations are home to highly detailed animal images, along with artistic human handprints painted onto cave walls.

Out of the two locations, it’s the European one that’s the most famous—and prodigious. To date, there have been about 350 painted caves found in Europe, and I say about because every year or two another one is discovered.3 Originally Europe’s caves were “only” thought to be between 25,000 and 30,000 years old, but new discoveries continually push that date further back in time. Now it’s possible that some of the art contained within them is perhaps 40,000 years old.

Europe’s painted caves have been the subject of much debate over the last 130 years, and no one is exactly sure just what went on in them. All we can say for sure is that the 350 or so locations discovered so far feature incredible artwork, generally of large mammals, along with a few anthropomorphic figures that might be the first “gods” ever sketched by human hands. It seems probable to me that the caves served some sort of spiritual purpose, but that’s impossible to prove definitively.

If the caves did serve some sort of spiritual purpose, then they represent the first long-lasting spiritual tradition ever practiced by human beings. People prayed or did whatever they did in Europe’s painted caves for thousands of years, from 38,000 to 12,000 BCE, and perhaps longer than that. In 1458 Pope Callixtus III condemned a group of Spaniards for performing rituals in one of the painted caves.4 Now that’s a religious practice that can be traced to the literal Stone Age! (Sadly, the rituals that were condemned were not specified.) The kind of spiritual longevity in evidence at the caves is unprecedented. By way of comparison, people have only been worshiping recognizable pagan gods for the last 5,000 years!

I’ve always believed that the caves served some spiritual purpose, and I believe that for a variety of reasons. The first is just the level of sophistication found in many of the paintings and etchings (while commonly thought of as “painted caves,” many of the images in them were carved into cave walls); serious work went into their creation. Images were often painted on ceilings and hard-to-access areas, which means they weren’t just random images. Someone (or a group of someones) did some actual planning.

The painted caves were also created in large underground cave systems, which means one “cave” might have dozens and dozens of rooms, with the last “room” thousands of yards away from the surface entrance. Isolated, large, dark spaces are also especially disorienting. Going into a dark cave separated from other humans by long distances would have resulted in a completely altered state of consciousness. What better place for a spiritual rite?

The most well known of Europe’s painted caves is probably Lascaux in Southwestern France, which has a little something for everyone. There’s a large room sixty feet long and twenty-one feet high that is full of bulls, and another very narrow room that features mostly images of cats. Lascaux is also home to a few rather mysterious images. The first of those is a unicorn, located near the cave’s entrance (and we know it’s a unicorn and not a mistake because every other horned or antlered animal in the cave is clearly shown with two protrusions on their heads). A remote part of the cave features a painting of a birdlike man with a bison; it’s the only representation of a human on Lascaux’s cave walls. Some speculate that the figure might represent a shaman walking between the worlds.5

While the images at Lascaux are the most well known, my favorite painted cave is the Grotte des Trois-Frères, the “Cave of the Three Brothers,” also in present-day France. Trois-Frères is relatively modern by painted cave standards, at only 15,000 years old, but what it lacks in age it makes up for in mystery. Trois-Frères cave is home to what might be the first ever image of the Horned God.

In a small room deep inside Trois-Frères, an odd mix of stag, owl, and man stands watch. Nicknamed the “Sorcerer” by archeologist (and monk) Henri Breuil, this cave painting was later linked to the Horned God of the Witches by English Egyptologist and historian Margaret Murray. It’s impossible to say whether the Sorcerer at the Cave of the Three Brothers is directly related to the male deity honored by many Witches today, but it’s an impressive figure.

Measuring about thirty inches tall and eighteen inches wide, the Sorcerer is positioned at Trois-Frères to be instantly visible when people walk into his room. Mentioning the specific positioning is important because it seems to indicate that whoever created the figure did so rather deliberately. In addition to his specific placement in the room he occupies, the Sorcerer is a combination of both engraving and paint. Everything else at Trois-Frères is one or the other, but never both.

The Sorcerer is the most famous image from Trois-Frères, but he might not even be the most interesting one. Closer to the cave’s entrance there’s another animal/man hybrid figure, this one featuring the head and torso of a bison and the legs and feet of a human. In addition, a small erect phallus can be made out in the engraving. Bison-Man seems to be carrying either a bow and arrow (which would be really incredible since the engraving predates such sophisticated technology) or a nose flute; no one is exactly sure. Gazing directly at Bison-Man is a panicky-looking cow that seems to realize its end is near.

The images at Trois-Frères cave are worth commenting on because they could represent a significant step in religious development. They could also just be depictions of hunters dressed in animal skins, or perhaps a shaman in the middle of a spirit journey. It’s unlikely that we’ll ever know for sure. While Europe’s painted caves represent a significant step forward in human communication, there’s not enough there to figure out the specifics.

One other thing we do know about the caves is that the majority of the images in them were painted by women. Many of the paintings across France and Spain were “signed” by the artists themselves, who left their handprints behind. Close examination of those handprints reveal that they were overwhelmingly female.6

Why write about 30,000-year-old art in a book about magical books? Perhaps because the ancient cave painters treated the walls of Mother Earth much like we do a modern-day Book of Shadows. The walls of places like Lascaux might be some of the first BoS’s in existence, sketching out a religious and spiritual practice that today we can only speculate about.

From Symbols to Writing to Books

Modern alphabets evolved from pictographs in ancient Sumer (southern Mesopotamia) and Egypt in the middle of the fourth millennium BCE (350 BCE). Pictographs are small drawings that represent things or ideas. Eventually the pictographs began to represent not just objects and thoughts but also sounds. This represented a major development, but pictographic alphabets were generally cumbersome. Mesopotamia’s early writing system used 2,800 different characters. That’s a lot of symbols to memorize!7

After its invention in Sumer, pictographic writing eventually traveled to the Indus River Valley in 2500 BCE and later the Greek island of Crete in 1750 BCE and China in 1200 BCE. Because of the vast amounts of time involved, many scholars believe that writing didn’t diffuse throughout the world so much as emerge independently in a variety of cultures. The establishment of pictographic writing in the Olmec Empire (located in modern-day Mexico) in the year 900 BCE lends a lot of credence to that argument.8

I’d like to tell you that writing emerged so people could pay tribute to the gods, but it most likely evolved simply so they could keep track of goods and services in ancient Sumer. A pictograph of a fish was used to keep track of how many fish were received in a financial transaction, for example. Eventually the symbol of the fish came to represent a sound and, as time progressed, became more and more abstract before resembling something we’d think of as a letter today. Pictographic alphabets were so successful in the economic realm that they were then adopted by local governments to more effectively administer goods and services. The early reasons for writing were economic and not spiritual (though for some people the pursuit of money is close to a religious endeavor).

While the majority of early writing was for economic and administrative purposes (90 percent), the people of ancient Mesopotamia did use it for other things as well. The people of Sumer produced The Epic of Gilgamesh, the world’s first major literary work, and they also wrote down spells and other magical ideas. They also produced the world’s first pseudo-books by joining large clay tablets together.9

The Egyptians took the first big step toward the modern book with the invention of papyrus scrolls. Papyrus was an early form of paper, and sheets of it could be pasted together to form scrolls. Many of us today are familiar with The Egyptian Book of Coming Forth by Day, better known as The Egyptian Book of the Dead. This book was designed to be a guidebook for souls entering the afterlife. (Though it is often referred to in the singular, there was no “one” book of Coming Forth; the contents contained within these Books of the Dead varied from individual to individual.)

The most famous visual image from The Book of Coming Forth shows the weighing of the deceased’s heart by the jackal-headed god Anubis. Balancing out the scale is a feather representing Ma’at, the goddess of truth. Recording the results of the weighing is the ibis-headed god Thoth, who acted as a scribe in the Egyptian pantheon.10 Most Coming Forth books included a few magical spells to help with getting by such obstacles.

The funerary scrolls of the Egyptians were visually stunning, but it’s the Greeks who took the use of the scroll to the next level. Greek scrolls were generally twenty feet in length but could be as long as a hundred feet! 11 In addition to long scrolls, the Greeks also invented the first modern alphabet in the 700s BCE. The invention of the Greek alphabet didn’t occur in isolation (the Greeks based their system on a Phoenician one), but what makes the Greek version unique is that it was the first one to include vowels. Use of the Greek alphabet isn’t all that common today, but the Latin alphabet (which you are currently using to read this book) is based on the Greek one, meaning its influence is still being felt today on a daily basis in much of the Western world.

Scrolls served the Greeks and later the Romans extremely well for several centuries but eventually gave way to the codex, the first real book, beginning at the start of the modern era.

The codex evolved out of the wooden tablet notebooks used by many in the Roman Empire for note taking and grew in popularity because it was less cumbersome than a scroll. The adoption of the codex was assisted by the rise of Christianity beginning in the year 300 CE. Being a people “of the book,” Christians preferred the codex to a scroll because it was easier to look up passages in a codex.12

Most codices have pages made of parchment (made from animal skin), because it was more durable than papyrus though much more expensive. In the twelfth century, Europe eventually moved to modern paper, a second-century Chinese invention that slowly moved through the Middle East before arriving in Europe. The introduction of paper led to a large increase in the number of codices being produced.

In the year 1450, the codex would give way to the book thanks to the invention of movable type by Johannes Gutenberg in Germany. Gutenberg is generally credited with inventing the printing press, but people had been printing on large wooden blocks for a couple of centuries. The invention of movable type made the enterprise cheaper and more efficient. Most early books were written in Latin and Hebrew, but starting in the 1550s books began to be printed in languages that more people actually spoke and read. It was at this point that magical books began to explode in popularity, even if they weren’t particularly beloved by churches and governments.

A Few Legendary Magical Writers

The history of magical books and grimoires is littered with legendary writers, both historical and mythical. In order to give their works an air of legitimacy, many medieval and Renaissance writers attributed their books to figures from history and myth. Forgeries of this sort are nearly as old as the written word and can be found in religious texts such as the Bible. (No one really thinks Matthew, Luke, Mark, and John wrote the books that contain their names.)

There are dozens of influential magical writers, but the following are a few of the more important ones not written about anywhere else in this book.

Moses

Most of us today know Moses for leading the ancient Israelites out of Egypt and sharing the Ten Commandments, but beginning in the fourth century CE he began a second career as a writer of magical books. Most of the books from that era have been lost, but the Eighth Book of Moses survived and, in addition to including a few magical spells, instructs users on how to meet the gods (and that’s gods plural—fans of Moses the magick writer weren’t necessarily Jewish or Christian).

“Moses” went on to write lots of other books in the centuries following his death. Works attributed to him magically appeared throughout the Renaissance and even into the modern era. Before his sojourn into magical texts, Moses was already well known as the writer of the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Old Testament, sometimes called The Five Books of Moses), so his literary pedigree appealed to forgers. In addition, he was a mortal with a direct pipeline to the God of the Old Testament, and who knows what else might have been whispered to him on Mount Sinai when he received the Ten Commandments?

The popularity of Moses has continued unabated into the modern era. He is still a popular figure in the magical tradition of Hoodoo and is especially beloved by many in the African-American community due to his links to ancient Egypt.13

King Solomon

The most well-known name in magical forgeries is that of King Solomon. He is the alleged author of the most famous grimoire ever written, The Key of Solomon (more on that later), and several other magical books. Solomon’s popularity as a magical author can be attributed to many factors. Legend credits him with writing several books in the Old Testament (Ecclesiastes, Proverbs, and Song of Songs) and overseeing construction of the first Jewish temple in Jerusalem. (Architecture on such a large scale was often seen as magical.) Solomon was also well known for his wisdom—wisdom that many thought also pertained to the magical arts.

Despite his legendary wisdom, Solomon is portrayed as a rather flawed person in the Old Testament. His worship of Yahweh was impure, and Solomon was said to have built temples for several gods other than his own. He was also said to have had over seven hundred wives and three hundred concubines, most notably the Queen of Sheba. His spiritual philandering made him a popular figure in magical circles outside of monotheistic ones, a popularity that continues to the present day.

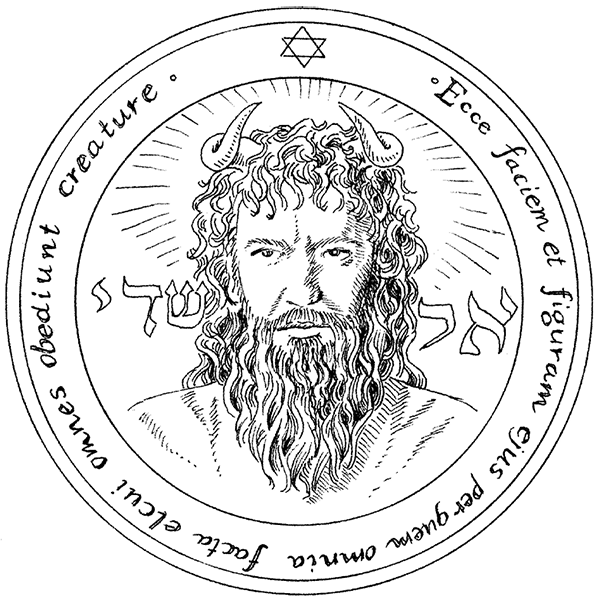

Hermes Trismegistus

The figure of Hermes Trismegistus is a complicated one. He is sometimes written about as a mortal man and other times as Hermes the Greek god (or Mercury in the Roman pantheon). Most scholars see the figure as a blending of the Greek Hermes with the Egyptian Thoth, god of wisdom. Hermes was such a popular figure during the classical era that some writers claimed he was the grandson of Moses, so desperate were some Christians to include him in their magical formulations!

Hermes Trismegistus was credited with writing several ancient magical texts, and his name was attached to several texts in the later medieval period. The most famous of those was The Emerald Tablet (which we will discuss shortly), which came to the Western world via the Middle East. Hermes was a popular figure in Muslim areas as well, and for centuries his name was nearly synonymous with magical practices.14

Henry Cornelius Agrippa (1486–1535)

Agrippa is most famous for writing what are commonly known today as the Three Books of Occult Philosophy. Born to minor nobility in Cologne, Germany, in the age of the Holy Roman Empire, Agrippa became interested in magick at a young age. He traveled widely during his lifetime and worked as a physician, soldier, lawyer, and theologian. It was his work as a theologian that gave his magical books an air of legitimacy among Christians.

Curiously, Agrippa wrote his most famous occult books as a young man but didn’t release them to the general public until a few years before his death. By that time he had grown uncomfortable with some forms of magick, which makes his decision to publish his Books of Occult Philosophy all the more curious. Agrippa became such an important figure in the magical world that a later Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy was written under his name several decades after his death.15

Faust/Faustus

Most readers are probably familiar with the legend of Faust, and how the famed magician sold his soul to the Christian Devil for wisdom and material wealth. But in addition to being a figure in German folklore, Faust may have been based on a flesh-and-blood individual, Dr. Johann Georg Faust. The real-life Faust is also said to have gone by the name Georgius Sabellicus and was once referred to as “a vagrant, a charlatan, a rascal.”16 A contemporary of the Protestant reformer Martin Luther, the real-life Faust is said to have died around 1540.

After his death, the legend of Faust as a diabolical magician began to take on a life of its own. Faust entered the English-speaking world through Christopher Marlowe’s play Doctor Faustus, which was first published in 1604. Several German texts attributed to Faust himself began to appear in the eighteenth century.

Eliphas Lévi (1810–1875)

Eliphas Lévi is one of the founders of the modern occult movement, weaving the tarot, Kabbalah, and ceremonial magick together into one tradition. He also introduced a whole host of figures and symbols into Western occultism, including the winged-goat-god Baphomet and the pentagram.

Lévi’s most famous book was Transcendental Magic: Its Doctrine and Ritual, published in the 1850s in two volumes in his native France and later translated by Arthur Edward Waite and published in one volume in English in 1896. Lévi was a towering figure in nineteenth-century occultism, and his work is still cited today.

Aleister Crowley (1875–1947)

Aleister Crowley is probably the most famous occultist of the last two hundred years and certainly one of the most influential. He was a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and after he was kicked out of that organization, he went on to found other magical groups before eventually rewriting the rituals of Ordo Templi Orientis (more commonly known as the O.T.O.) and becoming the head of that order.

Crowley wrote dozens of books over the course of his life (both fiction and nonfiction), but the two most influential were perhaps 777 and Other Qabalistic Writings and The Book of the Law. 777 is mostly a list of correspondences pertaining to the Kabbalah, and the current version of the book was assembled after Crowley’s death by occultist and writer Israel Regardie. The Book of the Law allegedly contains revelations from the Egyptian deities Nuit, Hadit, and Ra-Hoor-Khuit and became the central text of Thelema, a religious and magical system based on the writings of Crowley. The phrase “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law” first shows up in The Book of the Law.

Every Trick in the Book:

The Emerald Tablet

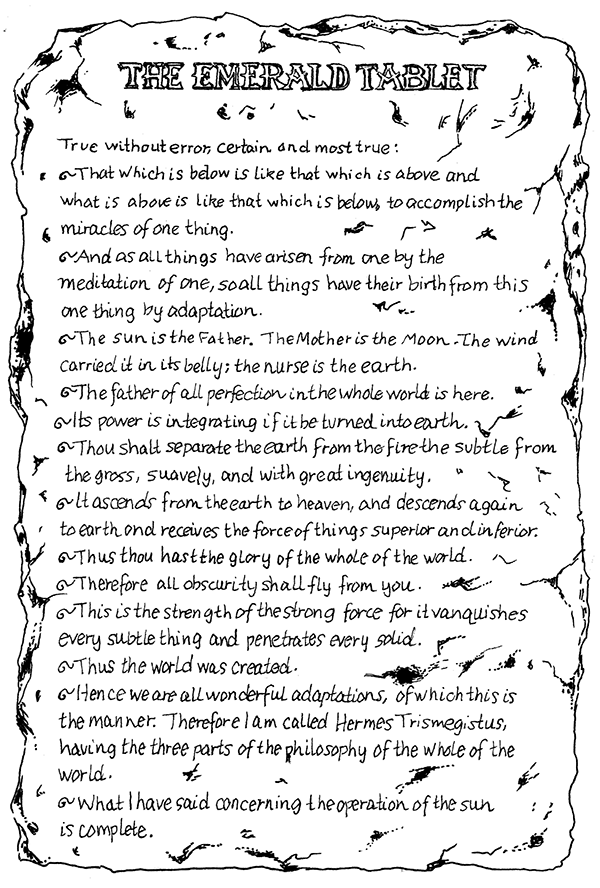

the emerald tablet of Hermes Trismegistus is one of the foundational texts of Hermeticism. Some readers may be familiar with the Hermetic tradition, a religious and philosophical tradition based on the writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus. It is an influential strand of the Western esoteric tradition.

Hermeticism was strongly shaped by Neoplatonism and went on to heavily influence Western occultism from the Renaissance forward. It could be argued that much of the magick practiced in Wicca today is Hermetic in origin; this philosophy is inscribed in the practices of the Golden Dawn and through that source found its way into Wicca.

Occultists have long believed that The Emerald Tablet is powerful and meaningful. Some have argued that it is part of The Corpus Hermeticum (the writings attributed to the mythological Hermetic founder, Hermes Trismegistus), while others have argued that it is older than most or all of the other writings.

Either way, the text is relatively old. It has been treated as one of the foundational texts of Hermetic tradition and Western alchemy since at least the twelfth century. Commonly known as The Emerald Tablet or sometimes Tabula Smaragdina, it is a poem or incantation of somewhere between a dozen and twenty lines, depending on the translation.

The earliest Western sources of this document are Latin translations from around the twelfth century. Older sources are from the Arabic. The Emerald Tablet was included in a book of wisdom titled Kitab Sirr al-Asrar (translated into Latin as Secretum Secretorum), which was supposed to be a translation of a letter from Aristotle to Alexander the Great.

There are a number of translations of The Emerald Tablet, and there is no one original from which they all have come. While people have long considered The Emerald Tablet to be of truly ancient origin, the earliest provable source comes from around 800 CE, in Arabic.17

The Emerald Tablet

When it comes to magick, the most famous line from The Emerald Tablet is “As above, so below.” What is less well known is that this is part of a longer line: “That which is above is from that which is below, and that which is below is from that which is above, working the miracles of one.”

From an occult perspective, perhaps the two most important things to know about The Emerald Tablet are that it is powerful and of great age and that it can be turned to any end. This short text can be read in many ways. Needham’s translation posits a Chinese origin for the original, while others have read it as a summation of Christian spirituality. Like many things that are powerful, it seems to reflect the soul of whoever looks into it.

Christopher Drysdale

Christopher Drysdale is an animist,

martial artist, shamanic practitioner,

healer, and meditation instructor.

He’s been Pagan for more than

twenty-five years and has a

master’s degree in anthropology.

A Few Famous Magical Books

History is littered with dozens and dozens of magical books worth noting, but sadly we don’t have the time and space in this volume to profile all of them. What follows are a few of the most influential and notorious magical books ever published.

The Greek Magical Papyri

Written in Greek but generally found in and associated with Egypt, The Greek Magical Papyri are a series of texts dating from between 100 BCE and 400 CE, generally involving the invocation and summoning of various gods and goddesses. Much of the material in the Papyri vaguely resembles the ritual structure of modern Witchcraft. The language used is often rather garbled and hard to understand, making the intent of some rituals difficult to figure out. The Papyri are not one cohesive body of work but represent a popular magical tradition, one that included both ancient pagan and Jewish ideas.18

The Book of Kells

The Book of Kells is one of the most beautiful codices ever put together but is not a grimoire or spellbook. It’s actually a Latin version of the New Testament gospels, put together sometime around the year 800 CE. What makes it magical are the illustrations, which are considered to be some of the finest surviving examples of ancient Celtic-British art. I’ve seen numerous Witches with BoS’s featuring reproductions of the artwork in Kells. The 2009 movie The Secret of Kells imagined the creation of the book as a coming together of Celtic-Pagan and Christian elements (and it comes highly recommended!).

Three Books of Occult Philosophy

by Henry Cornelius Agrippa

Agrippa published volume one of his magnum opus in 1531, with the other two volumes appearing two years later (though all three were written decades earlier). Agrippa’s books are not just treatises on the Kabbalah; they also contain a lot of natural magick and are still seen as some of the best books on the subject centuries later.

The Voynich Manuscript

The Voynich manuscript is not really a grimoire (as far as we can tell), but it is a fascinating and baffling little book. Consisting of striking pictures and an unknown alphabet, the Voynich manuscript was probably composed in fifteenth-century Italy (at least according to carbon dating) but has never been fully translated. The manuscript is probably most famous for containing pictures that resemble North American plants, created decades before Columbus arrived in North America.

It may not remain a mystery much longer. In 2015 a linguistic professor in the United Kingdom claimed to have translated a few words in the book. And in 2014 botanists from Delaware State University claimed to see similarities between illustrations in the Voynich manuscript and those in a sixteenth-century herbal manual from Mexico.19 Even if the manuscript is translated, more mysteries remain. The Hungarian Rohonc Codex is almost as old and also has never been translated.

The Discoverie of Witchcraft by Reginald Scot

One of history’s most important and influential magical texts was meant to be a repudiation of Witchcraft and not an endorsement, but it’s funny how things work out sometimes. Published in 1584, Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft contained so much information that it could probably be labeled as the first magical grimoire in the English language. Scot’s intention was to discredit magick, superstition, and Catholicism, but instead, he published a magical reference book that would be treasured and utilized right up until the end of the nineteenth century.20

Scot’s book was full of magical spells and formulations, and by including them, he hoped to prove that magick was silly and the province of the uneducated. What Scot didn’t count on was the appetite for magical books in Britain at the end of the sixteenth century. Most of his readers simply skipped the pages debunking magick and went right for the spellwork. Scot did such a tremendous job of documenting magical practices that the last third of his book truly reads like a grimoire.

The Magus by Francis Barrett

The Magus is not particularly original, mostly being a synthesis of other existing texts (most notably Agrippa’s Books of Occult Philosophy), but it would go on to influence a whole host of occultists after its publication in 1801. Barrett’s book simply looks magical; there are formulas and sigils on nearly every other page. It was one of the few occult manuals to be published in English at the start of the nineteenth century.

The Long Lost Friend by John George Hohman

The Long Lost Friend is one of the most influential American grimoires ever. Originally published in 1820, it’s been in print pretty much ever since and, because of its availability, has influenced a large number of magical traditions. Spells from The Friend can be found in Santeria and Conjure and have appeared in some modern Pagan books and blogs. Nearly two hundred years old, the tradition of The Long Lost Friend is still going strong.

The Friend was written and/or assembled by a Pennsylvania Dutch immigrant named John George Hohman, who arrived in the United States from Germany in 1802. Like most of the Pennsylvania Dutch, Hohman spoke and wrote in German, and his book was not translated into English until 1842.21 Hohman collected the spells in his book from a variety of sources, though most of them were lifted from previously published German magical books. Interestingly, one of Hohman’s spells comes from the “Senate of Pennsylvania.” 22

Hohman’s book is an example of “House Father Literature” (the literal translation of Hausväterliteratur), a genre of German writing designed to appeal to those of limited means who owned property.23 House Father Literature was mostly a collection of useful advice, things like herbal remedies and simple home remedies. Sometimes these books included things we would recognize as spellwork, but more often than not they didn’t. A House Father Book might be assembled by the home owner (very much like we might put together a Book of Shadows!), and those who used preprinted books often added their own spells and charms in the margins. House Father Books were often handed down to sons and daughters, and some were even written in code.

Sator Square

If this sounds all rather magical and witchy, it mostly is, but authors of books like The Long Lost Friend took pains to establish their Christian bona fides. Hohman began his book with a note asking “the Lord” to bless his work, and many of the spells in The Friend rely on Christian and Jewish figures from the Bible. Those figures are a bit garbled though, and one spell includes the baby Jesus, the Apostle Paul, and the Prophet Daniel. Many of the spells in The Friend are legitimately old, and spellcraft such as the Sator Square (and its variants) can be traced back to pagan antiquity.

Aradia by Charles Godfrey Leland

Originally published in 1899, Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches is alleged to contain some of the rites and magical workings of a group of Italian Witches. It’s a fascinating peak into a Witchcraft that’s much more aggressive than what most Witches practice today. Aradia is a goddess of liberation and the daughter of the Roman Diana and Lucifer, god of the Morning Star. Some of the text within Aradia was later adapted and included in the BoS’s of many modern Witches.

Every Trick in the Book:

A Modern Witch

& The Egyptian Book of the Dead

as a witch who is also a reconstructionist, naturally my little book of ritual work includes spells and procedures that are drawn from ancient records (in my case, Egyptian). When constructing a spell or ritual based on an ancient text, a Witch first needs to be familiar with the assumptions embedded in the original magical culture of the text. Not only will the words refer to mythology and lore, but they may also draw upon color symbolism, numerology, and unfamiliar magical tools and supplies, and it will be difficult to make a good adaptation of them without at least knowing what those things are and how they work.

The more knowledge one brings to the table about how ancient people constructed their spells and rituals, the more potent an adaptation can be. This knowledge will also help one find resources for various types of spells; it will be easier to figure out where to go to start building a cleansing or a blessing or a curse or a prayer if one knows where to look for them.

Suppose I wanted to construct a countercurse for someone stealing my magick. This is a concern that is expressed in spell 31 of The Egyptian Book of the Dead as well, since spirits traveling in the otherworld are very dependent on their magical prowess for their health and safety. In spell 31, the forces that attempt to steal magick are described as crocodiles; while the crocodile has many possible interpretations, in this case the primordial predator with the power to drag something down into the unreachable depths of the water is most relevant. The illustration shows a man striking a crocodile with its head turned away with a magical scepter; “turning the head” not only prevents a spiritual bite but also redirects the menace back toward its origin. The heads of the beasts are turned with the power of their names.

The heart of this ancient spell contains three circles. As in many other cultures, in Egypt a circle is both protective and eternal, as its loop offers no vulnerabilities and neither a beginning nor an end. The circle of the heavens is mentioned, with magick laid in the encircling foundations of the cosmos; these circles are equivalent, with magick giving rise to the structure and order of the stars. Then, the mouth itself, with the circle of lips, contains magick. As these circles are all linked, they guarantee that magick must remain in the possession of the speaker, not only for their own security but also to sustain the hours themselves.

After the protective circles are invoked, the magician then concludes with aggressive declarations, claiming the ability to threaten the crocodile itself. As the crocodile’s weapon is its toothy mouth, the Witch’s counterweapon, also, is a toothy mouth.

Once an ancient spell becomes familiar, with its symbols and relationships known, it can be adapted for a modern grimoire. Further, the skills used to breathe life into old texts can be used to create new spells that draw upon those same mythic resonances, lending a particular flavor to the Craft.

Kiya Nicoll

Kiya Nicoll is a Witch and Egyptian

reconstructionist from New England,

where she lives with her family.

She is the author of The Traveller’s

Guide to the Duat, a lighthearted

riff on The Egyptian Book of the Dead,

as well as a variety of poetry and essays.

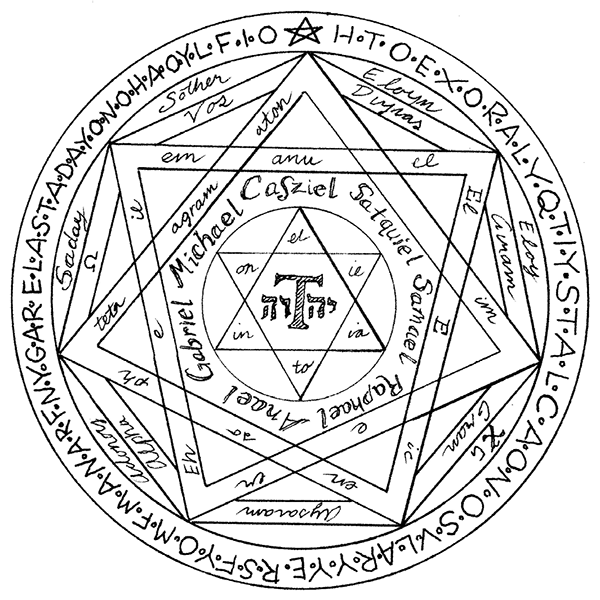

The Key of Solomon the King

(Clavicula Salomonis)

Some grimoires are just more important than others, and that’s certainly true in the case of The Key of Solomon (sometimes known by its Latin name, Clavicula Salomonis). I’m of the opinion that it’s the most influential grimoire in the history of Witchcraft, and its influence has endured all the way to the present day. Many of the spells, consecrations, and conjurations contained within it are similar to the rites found in many modern Witchcraft traditions. It even calls for the use of a black-handled knife, centuries before the word athame came into vogue.

Allegedly written by the Old Testament King Solomon, the Clavicula was probably composed in the fifteenth century and originally written in Greek. In its earliest form it was titled Little Key of the Whole Art of Hygromancy, Found by Several Craftsman and by the Holy Prophet Solomon. (It’s no wonder the abbreviation The Key of Solomon became more popular.) By the sixteenth century the treatise had been translated into Latin and Italian,24 and in the late nineteenth century it was finally translated into English.

Solomon has been credited with composing various grimoires over the centuries, and the Clavicula is often confused with a similarly titled work generally known as The Lesser Key of Solomon. None of those other works by Solomon is as notorious, though, as the Clavicula, probably because the rest of them don’t contain as much detailed information on summoning demons (usually referred to as “spirits” in the text). The Clavicula also contains rituals and spellwork advocating the use of animal sacrifice. With contents like that, it’s easy to understand why a lot of Christian crusaders really disliked The Key of Solomon.

Seals of Solomon

Despite the references to blood sacrifice in the text (which are rare), most of The Key is rather benign. Much of the book consists of prayers to the various names of the Christian God and invocations to various angels. The first few chapters of the book are generally concerned with the proper days and hours for spellwork. According to the author of the Clavicula, every day is ruled by a particular planet (Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, the Sun, Venus, Mercury, and the Moon), with each hour of the day also ruled by a specific planet.

In chapter 2 of The Key, the author assures us that the “Days and Hours of Venus are good for forming friendships; for kindness and love; for joyous and pleasant undertakings, and for travelling.” Using the tables in The Key, the aspiring magician would be advised to perform a spell for love on a Friday (ruled by Venus) at 1:00 AM, 8:00 AM, 3:00 PM, or 10:00 PM, as these hours are also all ruled by Venus on Fridays. Many present-day Witches continue to follow such advice, though I don’t know very many who break it down to the exact hour.

In addition to the prayers and correspondences, much of The Key is dedicated to forty-four different “pentacles,” or talismans, with various attributes. Each of these sigils is consecrated to a different planet (and yes, I know that the moon and sun are not really planets, something “Solomon” in all of his wisdom was unaware of ). The pentacles themselves are generally made up of various astrological symbols and letters of the Hebrew alphabet. These “seals of Solomon” remain so popular that even today one can still find them as necklace medallions with relative ease. (I’ve seen almost all of them at Renaissance fairs and Steampunk conventions.)

From Grimoires to the Book of Shadows

While magical books and grimoires have been around for centuries, the term Book of Shadows is of relatively recent vintage. Before starting this book, I would have guessed that the term first showed up in Gerald Gardner’s novel High Magic’s Aid (1949), a book that contains a great deal of Witchcraft-like ritual. Gardner was the first modern, public Witch and is a pivotal figure in the modern Witchcraft revival. While I don’t think he “invented” Witchcraft, he did help refine it, and many of the terms and rituals we use today come from his influence.

Though Gardner doesn’t use the term Book of Shadows in High Magic’s Aid, he does write about the importance of Witch books. At the beginning of chapter 9, the book’s heroine, the Witch Morven, reveals a bit of information about the book she and her mother shared: “We [Morven and her mother] talked much of herbs and cures, of the means to overcome sickness, and there was a great book in which we recorded all our experiments.”

Gardner’s novel mentions a lot of other magical books too, but this is the only passage that articulates something similar to our modern BoS’s.

Gardner later wrote two nonfiction books about his Craft, Witchcraft Today (1954) and The Meaning of Witchcraft (1959). Out of those two offerings, it’s the first that mentions the Book of Shadows, though again, not by name. In chapter 4 of Witchcraft Today, Gardner writes about a warning placed on the first page of most Witch books and offers some information on how such a book is kept (“Keep a book in your own hand of write”), but he doesn’t give a specific name for such a book:

It was probably about this time that the practice of witches keeping records became common as the regular priesthood no longer existed and the rites were only occasionally performed.

In all the witch writings there is this warning, usually on the first page:

Keep a book in your own hand of write. Let brothers and sisters copy what they will but never let this book out of your hand, and never keep the writings of another, for if it be found in their hand of write they will be taken and tortured. Each should guard his own writings and destroy them whenever danger threatens. Learn as much as you may by heart and when danger is past rewrite your book. For this reason if any die, destroy their book if they have not been able to do so, for if it be found, ’tis clear proof against them. ‘Ye may not be a witch alone,’ so all their friends be in danger of the torture, so destroy everything unnecessary. If your book be found on you, it is clear proof against you; you may be tortured.25

A later passage in Witchcraft Today reveals additional details about the Witch’s book. In this instance the book serves as a document of a Witch’s spiritual beliefs:

The faith of the cult is summed up in a witch’s book I possess which states that they believed in gods who were not all-powerful. They wished men well, they desired fertility for man and beast and crops, but to attain this end they needed man’s help. Dances and other rites gave this help.26

Though Gardner states in chapter 3 of his text that “Witches have no books on theology,” 27 Witchcraft Today is peppered with smatterings of Witch ritual—ritual that’s most likely familiar to many contemporary Witches.

Later in Witchcraft Today, Gardner does provide a name for the Witch’s book in a section on the Witch’s garter, but instead of calling it a BoS, he uses the term Black Book. Other Witches would use this term in the years to come, most notably high priestess Patricia Crowther, one of Gardner’s initiates. Unlike the term Book of Shadows, there’s a bit of historical precedent for the use of Black Book. The Grimoire of Honorius (dating from the Middle Ages), which contains information on how to cast a circle, along with several magical spells, is sometimes called “The Black Book.” Gardner was known to own a copy of this grimoire.28

There’s a Scandinavian tradition of Black Books, which were generally handwritten books full of various folk magicks, including charms, spells, herb lore, and incantations. The Black Books of Scandinavia were popular for nearly four hundred years (1480–1920), which is not surprising.29 Magick was especially popular throughout Europe during that period, though that magick was rarely called Witchcraft and the majority of practitioners (if not all of them) generally thought of themselves as pious Christians. Whether or not Gardner and other English Witches were aware of the Scandinavian phrase Black Book is a question that may never be answered.

A reference to a “black book” also shows up in the works of Margaret Murray, one of history’s most influential Witchcraft scholars. In her books The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921) and The God of the Witches (1931), Murray argues that Witchcraft existed as a religion side by side with Christianity for several centuries before eventually being persecuted. While Murray’s arguments have been dismissed by the vast majority of scholars, she’s had a tremendous impact on modern Witchcraft.

In Murray’s work, Witchcraft books act much like contracts. Initiates into the Witch-cult were required to sign a book pledging service to their fellow Witches. This signatory book was generally controlled by the “Black Man” or sometimes the “Man in Black,” who served as a representative of the Horned God, a deity who was later equated with the Christian Devil. Quoting the records of a Scottish Witch trial, Murray’s book makes reference to a “Black Man” in a “[tattered] gown and ane ewill favoured scull bonnet on his heid; hauing and one black book in his hand.” 30

While Gardner did not use the term Book of Shadows in his published writings, initiates recall him using the term. In the book Fifty Years of Wicca (2005), Gardnerian initiate Frederic Lamond recalls Gardner telling him that the Book of Shadows “is not a Bible or Quran. It is a personal cookbook of spells that have worked for the owner.” 31 So at some point in the 1950s Gardner began using the phrase, and it’s been with us ever since; however, it’s doubtful the phrase originated with him.

Gardner may have adopted the term after reading an article on Sanskrit divination in a 1949 edition of The Occult Observer titled “The Book of Shadows.” The article told of an ancient book that taught how to “measure one’s shadow”—information that could foretell a person’s destiny.

Coincidently that particular issue of The Occult Observer contained an advertisement for Gardner’s High Magic’s Aid next to the article in question. In addition, both the magazine and Gardner’s book shared a publisher, Michael Houghton, who was the owner at that time of the Atlantis Bookshop, one of London’s premier occult bookstores both then and now.32

This is the most likely origin of the title Book of Shadows, but as we have seen, books like a Witch’s BoS have existed for centuries. As long as people have been working magick and worshiping the Old Gods, there have been magical books. Even if the term Book of Shadows isn’t exactly ancient, it’s a wonderful phrase and masterfully sums up the records and rituals of the Witch!

Magical Books in Pop Culture Today

Before writing this book, I had always assumed that mythology and popular fiction were littered with magical books and grimoires. But that’s just not the case, probably because a hero carrying a book into a fight with a vicious dragon just doesn’t work in film or in literature. I’d love to see Merlin pause to look up a spell before assisting King Arthur, but apparently no one in Hollywood agrees with me.

Even though magical books are rare in pop culture, they do exist, and some of them have even had a long-lasting and significant influence on modern Witchcraft. My wife assures me that Books of Shadows and other magical texts have turned up in The Vampire Diaries and The Secret Circle (both originally young adult books and later television shows). A little more my speed is the Grimorum Arcanorum, the most powerful spell-book ever assembled, at least according to the Disney cartoon Gargoyles.

The 1980s were an especially good time for magical books in film and literature. The original Evil Dead film from 1981 features a version of the fictional Necronomicon (see the following section). That book’s power in the Evil Dead was so strong that it spawned three sequels and a television series. One of my biggest disappointments as a child was that The Neverending Story actually ends. Both the movie (1984) and the book (1979 in German, 1983 in English) of the same name feature a magical tome that literally takes its readers into a magical realm. The lesson of the tale, lost on me as a child, is that the adventures found in books can continue in our minds as long as we wish.

The Harry Potter franchise has featured two noteworthy magical books, the diary of Tom Riddle and later Tom’s Potions textbook. Of course Tom Riddle is Lord Voldemort, so the books ended up being bad, but at least author J. K. Rowling understood the power of the written word. The 1993 movie Hocus Pocus also features a rather sinister and sentient book. Clearly Hollywood films are not out to help the reputation of magical books.

The long-running television series Charmed featured not just Witches but also a book of spells explicitly labeled as a Book of Shadows. The outside of that BoS, and the show’s opening credits, featured a symbol akin to a triskelion set inside a circle. Since being featured in Charmed, that symbol is sometimes now thought of as a Wiccan symbol and marketed and used as such.

The spellbook from 1998’s Practical Magic is nearly as famous in some circles as the movie’s actual stars (Sandra Bullock and Nicole Kidman). The book used for the film is what every Witch most likely wants their BoS to look like. It contains exquisitely drawn symbols and perfect lettering. The love for this particular movie prop has become so widespread in the Witch community that replicas of it are easily available today in Witch shops and online.

Magical books are still popular today, though they often don’t look like something we would call a grimoire. Rhonda Byrne’s 2006 The Secret looks like a self-help book but is actually a new spin on the grimoire. Using the old idea that “like attracts like” (something that every Witch worth their salt knows!), Byrne has become a millionaire and has sold millions of books. Maybe in a hundred years, when someone is writing a new version of this book, they’ll talk about Byrne’s book or one of the hundreds of Witchcraft books that have been printed in the last fifty years.

The Necronomicon

The bestselling grimoire of the past forty years 33 and the most notorious in pop culture is a rather slim volume of dubious origin allegedly written translated by a guy known only as “Simon.” Simon’s book is a hodgepodge of Babylonian and Sumerian myth, with a dash of Aleister Crowley, Western ceremonial magick, and horror writer H. P. Lovecraft (1890–1937) thrown in. The book gets its name from The Necronomicon by Lovecraft, who made the whole thing up.

The Necronomicon makes its first appearance in the H. P. Lovecraft horror story The Hound (1924) and subsequently appears in many of his other works. Lovecraft thought enough of his fictional book to write an entire short story (History of the Necronomicon) on its origins in 1927 (which was not printed until 1938, after Lovecraft’s death), with none of those details adding up to the tale spun by “Simon.” In the works of Lovecraft, The Necronomicon is both a mythology of his “Old Ones” (godlike characters such as the well-known Cthulhu) and a means of summoning them to Earth. It also serves as a common thread, providing some continuity between Lovecraft’s various works.

I find it interesting what Lovecraft’s History of the Necronomicon story is not. It contains no real details of what’s inside The Necronomicon. Instead, it’s a history of the book’s translations and origins, probably written to aid Lovecraft in keeping his book’s history straight. Lovecraft never composed a version of his Necronomicon to use as a writing reference. If he had, it might serve as a “real” version of his fictitious book.

Lovecraft had no real magical training and only a superficial interest in the subject. As a New Englander, he was influenced by the Salem Witch Trials, and that interest eventually led him to Margaret Murray’s The Witch-Cult in Western Europe, published in 1921. He was also familiar with the works of French occultist Eliphas Lévi and Englishman Arthur Edward Waite.34 The works of Lévi and Waite were readily available in the 1920s, and both leaned toward a magical-Christian cosmology. In other words, Lovecraft’s involvement in magick and the occult was practically nonexistent.

So the bestselling grimoire in my lifetime is a fiction, and yet at the same time it’s not. Simon’s book contains some real magical theory, and if someone chooses to perform the rituals in his book, it’s likely that things will happen. But it’s also a farce at the same time. Simon claims that his book is a translation of a ninth-century magical text written by a man calling himself “the Mad Arab.” 35 Of course no one has ever been allowed to see the original text, and it seems rather unlikely that an important ninth-century magical text would be completely unknown to scholars (and that it would be released to the world as a mass-market paperback book!).

Simon’s Necronomicon was not the first (or last) version of Lovecraft’s fictional grimoire; it was just the most successful. The earliest “version” of The Necronomicon was published in 1973 by Owlswick Press and consisted of an introduction by horror writer L. Sprague de Camp, followed by nearly two hundred pages in “Duriac,” a fictitious language. This might be the most useless of all The Necronomicons, though the publisher seems to have released this version with tongue planted firmly in cheek.

Necronomicon: The Book of Dead Names published by Neville Spearman in 1978 was an improvement over the 1973 version and again involved de Camp, who this time wrote the appendix. The introduction this time around was handled by Colin Wilson, one of the preeminent paranormal writers of the time. Most of the ideas in this book come straight from Lovecraft’s short stories, with the magical system owing a debt to grimoires such as The Key of Solomon. Considering the names involved, it’s surprising that this particular hoax wasn’t more popular.

Perhaps the best version of Lovecraft’s book is Necronomicon: The Wanderings of Alhazred by Donald Tyson. Published in 2004 by Llewellyn, Tyson’s book is not out to fool anyone. Instead, Tyson lovingly recreates Lovecraft’s mythos while chronicling the adventures of Abdul Alhazred (the Mad Arab). It’s more a story than a grimoire, but it does include information on how to summon Lovecraft’s Old Ones. Since the publication of Wanderings, Tyson has released three more books on the subject, each one refining and elaborating on his version of The Necronomicon.

Even with all the various versions of The Necronomicon currently in print (and now there are even Necronomicon-themed tarot cards), it’s the Simon version that still sits atop the best-seller lists. Originally released in 1977 by the publisher Schlangekraft, Simon’s book became a bestseller after it was picked up by Avon in 1980. Since then, his version of The Necronomicon has turned into a cottage industry, with The Necronomicon Spellbook, The Gates of the Necronomicon, and the “history” book Dead Names: The Dark History of the Necronomicon.

In my first outline of this book, I nearly put this bit in the section dealing with magical books in popular culture. But for thousands of people, The Necronomicon is a very real book of magick. I’m not a huge fan of “Simon” and his fictional works, but he’s simply the latest in a long line of magical forgers. Solomon didn’t write any of the magical books in his name either. If the magick in The Necronomicon (regardless of the edition) works for someone, and they use it responsibly, what’s the harm?

2 Pallab Ghosh, “Cave Paintings Change Ideas About the Origin of Art,” BBC News (October 8, 2014), www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-29415716.

3 Gregory Curtis, The Cave Painters: Probing the Mysteries of the World’s First Artists (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 15.

4 Gregory Curtis, The Cave Painters, p. 47. Despite me desperately wanting those rituals to somehow be connected to what went on there 30,000 years ago, it’s doubtful that they were. However, we’ll never know for sure!

5 Gregory Curtis, The Cave Painters, 114.

6 Virginia Hughes, “Were the First Artists Mostly Women?” National Geographic (Oct. 29, 2013), http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/10/131008-women-handprints-oldest-neolithic-cave-art.

7 Michael F. Suarez and H. R. Woudhuysen, eds., The Book: A Global History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 5.

8 Suarez and Woudhuysen, eds., The Book: A Global History, 5.

9 Ibid., 40.

10 Clive Barrett, The Egyptian Gods and Goddesses: The Mythology and Beliefs of Ancient Egypt (London: Diamond Books, 1996), 4.

11 Suarez and Woudhuysen, eds., The Book: A Global History, 43.

12 Suarez and Woudhuysen, eds., The Book: A Global History, 45–46.

13 Owen Davies, Grimoires: A History of Magic Books (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 9–11.

14 Antoine Faivre, The Eternal Hermes: From Greek God to Alchemical Magus, trans. Joscelyn Godwin (Grand Rapids, MI: Phanes Press, 1995).

15 Henry Cornelius Agrippa, Three Books of Occult Philosophy (1531; reprint, St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 1993), XV–XXXVIII.

16 Owen Davies, Grimoires: A History of Magic Books, 49–50.

17 Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, part 4 (Cambridge University Press, 1980).

18 Ronald Hutton, Witches, Druids, and King Arthur (New York: Hambledon and London, 2003), 119.

19 Allison Flood, “New Clue to Voynich Manuscript Mystery,” The Guardian (Feb. 7, 2014), www.theguardian.com/books/2014/feb/07/new-clue-voynich-manuscript-mystery.

20 Owen Davies, Grimoires: A History of Magic Books, 69–70.

21 Owen Davies, Grimoires: A History of Magic Books, 192.

22 John George Hohman, The Long-Lost Friend: A 19th Century American Grimoire, ed. Daniel Harms (Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 2012), 19. In 1802 a spell to prevent rabies was submitted to that body and ended up in the Senate record.

23 Ibid., 3.

24 Owen Davies, Grimoires: A History of Magic Books, 15.

25 Gerald Gardner, Witchcraft Today (London, Rider & Co., 1954), 43.

26 Ibid., 105.

27 Witchcraft Today was originally published in 1954 by Rider & Co. Since then the book has been reprinted at least half a dozen times by half a dozen publishers.

28 Sorita d’Este and David Rankine, Wicca: Magickal Beginnings (London: Avalonia, 2008), 44.

29 Ibid.

30 Margaret Murray, The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921; reprint, New York: Barnes and Noble, 1996), 35.

31 Sorita d’Este and David Rankine, Wicca, 42.

32 Doreen Valiente, The Rebirth of Witchcraft (Custer, WA: Phoenix Publishing, 1989), 51.

33 At last count The Necronomicon had sold over 800,000 copies. https://danharms.wordpress.com/2008/09/17/we-get-more-necronomicon-questions-part-2.

34 John L. Steadman, H.P. Lovecraft and the Black Magickal Tradition (San Francisco, CA: Weiser Books, 2015), 43–50.

35 Daniel Harms and John Wisdom Gonce III, The Necronomicon Files: The Truth Behind the Legend (Boston, MA: Weiser Books, 2003), 133.