Alphabets, Fonts,

Inks, and Symbols

In the process of creating a Book of Shadows, the most important tools we have at our disposal are our brains and the words, scripts, fonts, and symbols that go into our books. We use our minds to formulate our ideas, but we bring these ideas to life when we write them on a page or type them on a keyboard. It’s easy enough to compose a BoS using everyday language, but it’s much more magical to include a few things in code, a foreign language, or a magical alphabet.

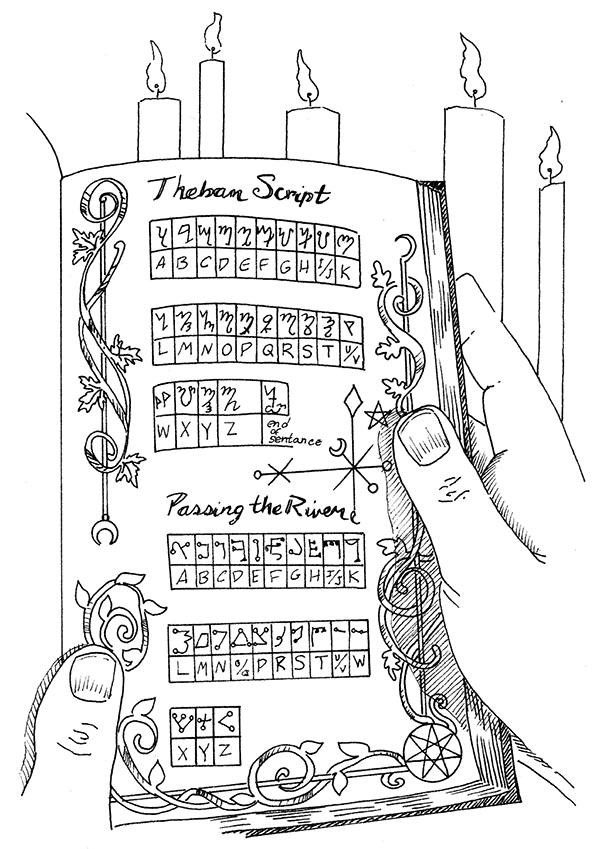

The most popular magical alphabet in many Witch circles is Theban. Despite its rather Egyptian-sounding name, Theban was developed in Germany during the sixteenth century either as a cipher or perhaps explicitly for magical purposes. It became popular in the magical community after its inclusion in Agrippa’s Third Book of Occult Philosophy and has been a part of the Western magical tradition ever since.

Agrippa wrote that magical alphabets were used among the ancients because it was “unlawful to write the mysteries of the gods with those characters with which prophane (sic) and vulgar things were wrote.” 47 While that’s not a law in Witchcraft, the use of magical alphabets has been a part of our Craft since at least the 1940s, when Gerald Gardner had his magical name (Scire) inscribed on a bronze bracelet in Theban.

There are Witches who have composed entire BoS’s in Theban, though the practice is not common. Today, Theban is used primarily in spellwork, where it’s thought that the extended level of concentration needed to write in Theban makes one’s magick more powerful. Names and magical mottos are often inscribed on magical tools in Theban, as are certain attributes of specific tools. (For example, the word Will might be written on an athame, as it’s a tool used to project one’s will.)

Nearly as common as Theban is the script known as Passing the River (sometimes also known as Passing of the River), which also appears in Agrippa’s book. He lists it as one of the languages of the Kabbalah and includes it alongside two alphabets of his own devising, Malachim and Celestial. Unlike Theban, which looks very rune-like, all of Agrippa’s “celestial writing systems” are quite fluid and contain lots of small circles.

Theban script and Passing the River

Another common alphabet in Witch circles is Enochian, which is said to be the language of angels. Enochian was first used by the Englishman John Dee (1527–1609) and his spirit medium Edward Kelly (1555–1597) in their private journals. Several hundred years after the deaths of Dee and Kelly, Enochian began to appear in magical orders such as the Golden Dawn. Magical systems based on Enochian are modern inventions, but that hasn’t stopped the alphabet from gaining in popularity.

The Norse runes are used in spellwork and divination and might be the most commonly used magickal alphabet in the Pagan community. While they don’t appear in this chapter, I haven’t forgotten about them. There’s an extended look at them in chapter

7 in the section “Odin and the Runes.”

Ogham

Ogham (sometimes spelled ogam) is an ancient Celtic script found predominantly in Ireland and western Britain. The ancient Celts used it primarily to identify memorials to the dead, but it most likely had other uses as well.48 Until quite recently, ogham was associated primarily with the ancient Druids and ancient Celtic Paganism and was used by a variety of Pagans and Witches for all sorts of magical purposes.

Ogham

Medieval Irish literature linked the symbols in ogham to specific trees and plants, an association further popularized by the English writer Robert Graves (1895–1985) in his book The White Goddess (1948). Because of this, many Pagans today refer to ogham as the “Tree Alphabet,” and its letters are often used to represent particular types of trees. This has made ogham very popular in a lot of magical operations, and its letters often function like the Norse runes. The ogham letter duir (see illustration), for example, is often associated with the oak tree and might be worn around the neck of a magical practitioner with an affinity for oak trees or their properties. (As someone whose coven is named “The Oak Court,” this is most certainly my favorite rune.)

Ogham was originally written on a straight line from top to bottom, making it a particularly challenging alphabet to use in magical operations. To get around this, many Witches and Druids today write it from left to right (like most of our modern alphabets) and forgo the long line that connects ogham letters together on ancient Irish monuments.

Foreign Languages and Magical Mottos

For the last five hundred years, the English-speaking world has often looked to other languages for magical inspiration. The first grimoires were generally written in Latin and Greek, and it sometimes took several centuries for English-language translations of such influential texts as The Key of Solomon to become readily available. Magical orders such as the nineteenth-century Golden Dawn required their members to have a working knowledge of Hebrew. As useful (and as magical) as I find the English language to be, it was not all that popular in magical circles until relatively recently.

I don’t know a whole lot of Witches who keep their BoS in anything other than their native language, but using another language is certainly an option. Writing one in German, Spanish, or French would probably help to keep it private and lend it an air of mystery. It would also maintain the long-standing tradition of magical books for English speakers being written in a foreign language.

Writing an entire BoS in a foreign language is most likely beyond most of us, but foreign phrases have a place in the BoS. Old spells cast in ancient Greek or Hebrew pack a bit of an extra wallop, and even Latin phrases have a touch of the exotic. Perhaps that’s why it was common in the Golden Dawn for every member to adopt a magical motto.

A magical motto is similar to a magical name in that it’s meant to emphasize the magical nature of the practitioner. Many who adopt a magical motto often use it as a name inside the circle, while others see it as representative of something deep inside themselves. The most famous motto in magical circles is perhaps Perdurabo, a term chosen by Aleister Crowley that translates as “I Will endure to the end” (the “will” being capitalized by Crowley to emphasize its importance to him).

English occultist and writer Dion Fortune chose Deo, non fortuna as her motto, which means “By God, not by chance.” Bible-related mottos were popular with many magicians; the American occultist Israel Regardie’s was Ad Majoram Adonai Gloriam (“For the greater glory of the Lord”). Mottos could also be regal and a bit pretentious. One of the founders of the Golden Dawn, Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers, chose ’S Rioghail Mo Dhream (“Royal is my race”) as his identifier. Mathers’s wife, Moina, used Vestigia nulla retrorsum, which translates as “I never retrace my steps.”

With Latin-to-English translation apps and pages on the Internet, coming up with a Latin magical motto is easier than ever. I recently added Et Qui Sapienter (“He who speaks wisely”) to the title page of my own BoS. When I showed it to my wife, she suggested I amend it to Et qui vult, loquitur sapienter (“He who wishes to speak wisely”). If you do add a magical motto to your own book, I suggest not sharing its meaning with a whole lot of people. It’s probably best to let people wonder.

The Creative Use of Fonts and Scripts

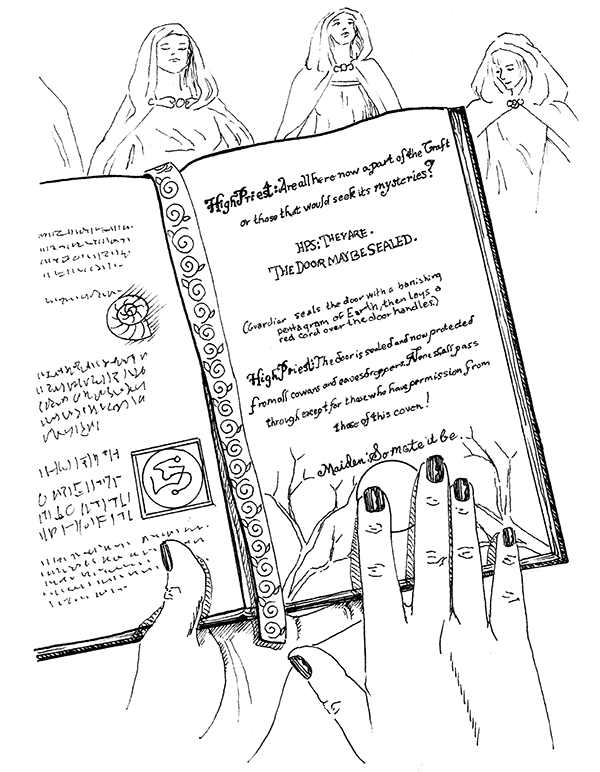

Several years ago, my coven presented a large ritual (200-plus people) at a public Pagan festival. It was a very “talky” ritual full of nineteenth-century English poetry and long passages borrowed from Freemasonry. Due to its length, none of us even really tried to memorize it, so we each made it a part of whatever BoS we had chosen to use for that ritual. I didn’t pay much heed to how things were arranged in each individual’s book until I looked in my wife’s BoS several months after the event.

Peeking into her book was like looking at an entirely different ritual. Each role in the rite had its own distinctive script. My lines were written in a small and claustrophobic sort of style, with each word separated by only the tiniest of spaces. The way she wrote my lines in her book made my contributions to the rite feel almost insignificant. Her lines, on the other hand, were written in a large, graceful, and flowing script that felt full of confidence and authority. In this version of the ritual, she and her goddess were the centerpiece of everything.

There were practical considerations for her approach in writing down this ritual, of course. By making her lines bigger than everyone else’s, she made them that much easier to keep track of and read during the ritual. But I think her way of doing things took all of this a step further. Every person involved in the ritual had their own personal style of script that seemed to reflect their personality.

Witches engage in all sorts of ritual, but many have trouble understanding the differences between a ritual with ten people and one with a hundred. Even when the words in a big rite are the same as in a smaller one, they often need to be read differently in order to convey what’s going on in the ritual. Public ritual in large spaces calls for big actions, along with slow, loud, and deliberate speaking. My wife’s way of writing down her lines was like a form of personal stage direction. How something is written down or typed up influences how we read it.

Magick and ritual are about breaking free of the mundane world, and there are few things more mundane than fonts such as Times New Roman or Helvetica. They make us think about work or paying the bills, not about the mysteries of the Lord and Lady. Simply using an unfamiliar yet appropriate font in a Book of Shadows is an effective magical trick. It takes the mind to a different headspace and reminds us that we are engaging in something out of the ordinary.

When I write things down in my BoS, I generally print, which is how I’ve written the majority of my life. (I stopped using cursive shortly after I learned to write it.) But print is perhaps the most mundane form of writing we have. It’s often far easier to read than cursive, but it’s easier to read because it’s generally boring.

The only time I really write in cursive is when I’m signing my name to something, and I’m always delighted with how it looks. My signature is a mess, of course, but it’s full of personality and energy. It represents me in a way that no other form of handwriting does. It’s the kind of personality I should be putting into my handwritten BoS.

Different fonts in a book

Most of us aren’t going to write our books in ogham or Passing the River, but we can write in cursive. A great BoS is more than just a collection of spells and rituals; it’s a document detailing who we are as individual Witches. Why not use a type of handwriting that reflects something about us as individuals?

Calligraphy

This is a style of decorative writing generally associated with broad-tip, antique-looking pens. I first became aware of it while studying American history in the fifth grade, but today it has other meanings for me; it’s the type of handwriting I most associate with magical things. The first modern Witches wrote in a very ornamental style in their BoS’s. This gave their work a timeless and archaic look, making it that much more magical. When we envision ancient wizards and sorceresses, we most likely picture them writing with a fluid hand in a beautiful script. Why not link what we do to such notions?

An effective Book of Shadows should most certainly be practical, but there’s no reason it can’t also be magical. Using decorative styles of writing and fonts outside the mundane is a way to break free from the ordinary and impart a bit of extra energy to our most important personal book.

Magical Symbols and Shortcuts

In the earliest BoS’s, Witches would often use a particular symbol to represent a ritual tool, a deity, or an idea. For many years this was something that could be done only with a handwritten BoS. When people began typing things out from a BoS or creating new pages with a word processor, they would sometimes leave a blank space to write in that special symbol later. Today, no matter how you create your BoS, it’s incredibly easy to use symbols in the text. Most word processing programs will let users add their own alphabets, along with various symbols.

Even the previously mentioned hard-to-use Theban script can be downloaded as a font. One doesn’t even have to really learn Theban to write (type) a BoS with it today. Others have already done the hard work and made sure that the equivalent to “e” in Theban ( ) shows up in the right spot on your keyboard. Of course downloading a font isn’t the same as really learning a different alphabet, let alone being able to read it.

) shows up in the right spot on your keyboard. Of course downloading a font isn’t the same as really learning a different alphabet, let alone being able to read it.

Most of us are probably not going to use Theban script or a particular set of runes to compose our BoS’s, and that’s all right. There are still some really handy little symbols we can use whether writing by hand or typing things out on the old keyboard. Most of them can be found in “Wingdings,” a collection of symbols available in most word processing programs (such as Microsoft Word) and in the “Character Viewer” if you are using an Apple product. Some of the symbols I use can also be found on a standard keyboard, and it’s easy enough to simply come up with your own.

My Favorite Symbols and Shortcuts

Why would anyone want to use symbols to represent words or ideas in a BoS? Many covens like to keep the names of their gods and goddesses secret, and using a symbol is a lot more elegant than leaving a blank space or a line in their BoS. Using a magical shorthand also means there are fewer characters to write down, which is especially useful if you are crafting your BoS the old-fashioned way. I also like using a shorthand because it helps to keep things just a little bit secret. If you or your coven adopt a few symbols for the BoS, then anyone reading your BoS will need help translating it. This is especially helpful if you want to reserve a rite, tool, or prayer for only your coven.

For many covens, oral lore is just as important as a BoS. Keeping a few things out of a BoS and whittling them down to symbols means that everyone has to eventually learn that oral lore for things to make sense. I remember my first extended look at a BoS filled with symbols that I was expected to know—it was intimidating. Maybe it makes me a bad person, but I like the idea of a book I’ve put hours and hours of work into being intimidating to someone outside the Craft (and even a few in it!).

Here are some of the symbols I use in my own BoS’s. This list is not meant to be exhaustive; it’s just a collection of a few things I use in my own practice and have found useful over the years. There are also some other symbols sprinkled into a few of the rituals in this book.

|

|

I use the slash if I’m saluting one of the quarters or raising my hand for some reason. |

|

|

I use this symbol for casting the circle. |

|

|

My coven uses a kiss as a greeting with some regularity. |

|

|

A sun symbol is perfect for the God. |

|

|

I use a circle for the moon, which is sacred to the Goddess. |

|

|

This symbol works for “As above, so below,” a familiar refrain in magical circles. |

|

|

Zeros work well for the circle and look different from the circle used for the moon. |

|

|

An upside-down triangle is a very common symbol for a first-degree Witch in initiatory traditions. |

|

|

A peace sign is perfect for the phrase “Blessed be.” |

|

|

I want something that says stop to represent the words “So mote it be.” |

|

|

A filled-in circle reminds me of an eclipse, which is a joining of the sun (male) and the moon (female), so it makes a handy symbol for the Great Rite. |

|

|

Squares and rectangles are easy representations of an altar. |

|

|

I use this symbol for the Wheel of the Year. |

If you do choose to use symbols, there are some important points to remember:

• Make sure that whatever you’re using is unique-looking, so you won’t get it mixed up with something else. There are lots of star symbols available on a keyboard, for instance, but they can easily run together in your brain. Also, some symbols look a lot like a letter of the alphabet, which can be confusing.

• I try to use the same symbols in my handwritten and typed-up BoS’s, so generally I only use symbols I can easily find on a keyboard.

• When typing in a symbol, make sure it’s big enough that you can see it easily. This sounds like a no-brainer, but it’s a mistake I’ve made before. If you’re using a small font size, some symbols look more like smears than symbols when printed.

• Make sure to be consistent! I keep a legend of the various symbols I use in things so I’ve got a reference point.

Symbols are a practical and attractive addition to any BoS. I highly recommend using them.

Homemade Ink and Pens

Most Witches don’t write their Books of Shadows with homemade pens and ink, but it can be done, and it’s not even all that difficult. Both items can be made with simple household items in a relatively short period of time. Homemade ink is often good for the environment too—there are many formulas for it online that are 100 percent organic!

Why make your own ink? Anything we create we infuse with our own energies, and the BoS is no exception. Using your own ink in a BoS or even a spell puts a little more “you” in it, and in magick that’s always a good thing. Writing with a quill pen and homemade ink can be challenging, and I wouldn’t recommend creating a whole BoS this way, but for one-off projects or especially important parts of a book it has value.

Even if you decide not to make your own ink, you can easily spruce up store-bought ink to make it more magical. Adding just a touch of your favorite essential oil will give it (and your BoS) a delightful scent. You can also crush up your favorite dried herbs and add them to your ink for a similar effect. You can buy ink today with glitter in it, but you can also add your own. This is especially useful if you want to charge the glitter and infuse it with a little extra magical energy.

Make Your Own Organic Red Ink

To make red ink you will need the following:

• ½ cup raspberries

• A strainer

• A bowl

• A potato masher or large spoon

• ½ tablespoon salt

• ½ tablespoon vinegar

• A fork or wire whisk

• A small jar or bottle to store your ink

Start by extracting as much juice as you can from the raspberries. I recommend using a potato masher to mush up the berries in a strainer and then pressing down on them with a large spoon. If you don’t have a masher, you can use a spoon for that too. Obviously you want the juice from the berries to go into whatever bowl you are going to mix all your ingredients in.

Once the juice is extracted, mix it with the salt and vinegar. I suggest using a fork or small wire whisk for the mixing. Once it’s all blended together, bottle it up and your ink is ready to go.

This rather easy formula can be used with any berry that stains. If you are looking for a dark or purple ink, blackberries are a good choice. If you can find the right shade of blueberries, you can make a nice blue too. Also, your ink will smell better than everyone else’s.

Make Your Own Black Ink

Black is generally the default color when people think of ink, and unless you are using blackberries, making black ink from scratch is a bit more involved than our raspberry-red ink. For black ink you will need the following:

• Carbon black (lamp black)

• A bad, sooty candle

• Several spoons

• Two small dishes

• Vodka

• Gum arabic (mixed with water)

• A small jar or bottle to store your ink

Black ink generally requires a small amount of carbon black (sometimes referred to as lamp black), which can be collected using candles or an oil lamp. The easiest way to collect carbon black is with a bad, sooty candle (think dollar-store candle—there’s a reason “organic” isn’t in the section title here). Beeswax won’t work; it burns too cleanly. After lighting your sooty candle, hold a spoon near the flame with the “bowl” part of the utensil touching the candle’s flame. The black that collects in the spoon is carbon black. To make ink, you will need a decent amount of it, so you may want to have a few spoons handy.

Put the soot in a small dish and mix it with some vodka; it will be paste-like at this stage. In a separate dish, mix some water with a bit of gum arabic (available at most craft stores), then add this to the soot and vodka. Continue adding small bits of water and mixing all the ingredients until you reach the desired consistency, then immediately use or bottle the ink. The gum arabic is what binds the ink to the page, so if your ink doesn’t “stick,” add a little bit more of it dissolved in water.

Feather Quill Pens

I have stained all sorts of things in my house while making ink and managed to burn myself once while collecting soot, but feather pens? Those are ridiculously easy to make. All you need are some long feathers (think at least eight inches long; a foot is even better), which you can buy at your local craft store or get from a poultry farm. (If you have any friends who buy an organic turkey from a local farm during the holiday season, ask them to pick up some feathers for you when they get their bird.)

All feathers have a bit of a natural curve. To make your pen, start by finding this curve. You’ll want your pen tip to follow the curve and point downward. Using a marker or pencil, put a small dot on the place where you’d like the pen tip to be. Set your feather on a cutting board and cut it with a sharp, heavy knife (don’t use a steak knife) so that you create a definitive point at the feather’s end. Depending on how fresh or processed your feather is, there could be gunk left inside of it at the quill’s point; that can be removed easily with a pair of tweezers.

And that’s it, really. Now you’ve got a quill pen to use with your homemade ink! If you want to get a little more fancy, you can trim some of the feather back to make it more comfortable in your hand. You can also paint on the feather’s surface or add a bit of glitter—whatever works. While I suggest turkey feathers (they just tend to be easier to get), goose and peacock feathers are good choices too.

Super Secret Witch Stuff—

Invisible Ink in a Book of Shadows

If you want to take secrecy to another level, you could always write your BoS in invisible ink. Most of us probably experimented with “invisible ink” made from lemon juice when we were children. It’s an easy trick. You just mix some lemon juice with some water, write with it on a piece of paper, then hold the paper up to a light bulb (or other heat source) to reveal the hidden message. This works well enough for single sheets of paper but is pretty impractical in book form. Fortunately, there are alternatives.

Today there are many different kinds of “ghost ink” on the market that are designed to be used with modern fountain pens. Ghost ink is an ink that’s invisible in normal light and can only be seen under black light. It’s a pretty cool-looking trick—that is, if you don’t mind everyone in your coven wielding a flashlight during ritual.

Ghost ink and homemade pens are not going to be for every Witch, but they can add a little extra enjoyment to your practice. When we take the time to make everything we do in circle and as Witches different from our everyday mundane lives, we are showing our tradition the respect it deserves and making the magick we create even more powerful.