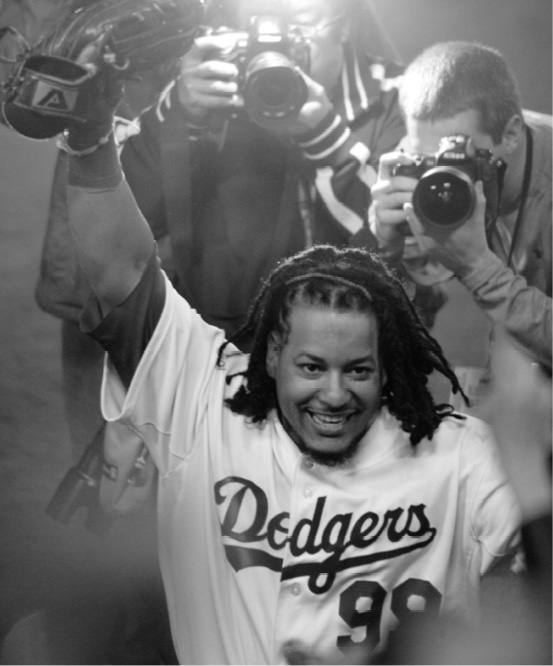

26. And a Manny Shall Lead Them

As their 2008 season wound down to its final innings, the Dodgers’ hopes appeared to rest on Manny Ramirez’s ability to hit a five-run homer.

Based on what he had done to that point, you half-believed he could.

The Dodgers were not a one-man band in 2008, their 20th season since the heroics of Kirk Gibson. But they did need something of a hero: someone who could push them past the two decades of postseason struggles that had limited them to a single victory. Someone who could provide the power for a team that hadn’t seen anyone hit more than 20 homers in a season since 2005. Joe Torre, the celebrated Yankee manager who had come out to helm the Dodgers following the 2007 season, couldn’t exactly be expected to drive in the runs.

It was for that reason that the Dodgers went out in December 2007 and got a big-name, slugging outfielder. The team signed free agent Andruw Jones, who had averaged 31 home runs per season with the Atlanta Braves and was still only 30, to a two-year, $36.1 million contract—the highest average annual salary ever for a Dodger. Jones was coming off the poorest season of his career to that point, but most people found easy enough to explain away to injury.

Instead, Jones faltered to an almost unprecedented extent. Arriving at spring training overweight, Jones never, at any point, found his swing. He had a .275 on-base percentage and .273 slugging percentage through May 18, when he was sidelined by torn cartilage in his right knee. Unable to salvage his season, Jones finished with three home runs and a 32 OPS+, the lowest by a Dodger with at least 200 plate appearances in 97 years. Instead of being carried by Jones, the Dodgers had to carry his dead weight.

For a while, Rafael Furcal helped them do exactly that. The shortstop—a former teammate of Jones in Atlanta—was his solar opposite, a ball of flame in contrast to Jones’ ice-cold bat. In his first 32 games, Furcal on-based .448 and slugged .597, positioning himself arguably as the NL’s most valuable player to that point. But the injury bug didn’t play favorites, striking Furcal in his back and taking him out of the Dodger lineup from May 5 to the final week of September. Within a week, the Dodgers had lost their projected and actual best hitters.

Add to this the struggles of 2007 staff ace Brad Penny, whose ERA more than doubled (3.03 in 2007, 6.27 in 2008) as he foolishly tried to pitch in pain before going on the disabled list for half the season, and the two-in-one-day spring training injuries to third basemen Andy LaRoche and Nomar Garciaparra, and you could get the sense that the 2008 Dodgers were a star-crossed team. Even though the division-leading Arizona Diamondbacks faded from their hot start, the Dodgers found themselves in the confounding position of being one game out of first place yet two under .500 (49-51) on July 22, when Colorado slaughtered them 10–1.

Four days later, the Dodgers acquired third baseman Casey Blake from Cleveland (at the cost of minor league pitcher Jonathan Meloan and catcher Carlos Santana, the 2008 California League MVP) to supplant Blake DeWitt and LaRoche. As the morning of the July 31 non-waiver trade deadline came, it seemed Blake would be the team’s big move for success.

Then came Manny.

In 2008, the Dodgers needed someone who could push them past the two decades of postseason struggles and bring in the runs. Manny Ramirez was nothing less than a dream hitter, hitting 17 home runs and slugging .743, and was one hit shy of batting .400.

Despite leading the Boston Red Sox to its first two World Series titles in nearly a century, hammering 274 homers in 71/2 seasons and posting a .430 on-base percentage and .601 slugging percentage for them in 2008, Ramirez had earned the enmity of much of Boston through some malcontent behavior—an incident of pushing a front-office employee here, allegations of dogging it there. His actions seemed a transparent ploy—in theory with the encouragement of his new agent, Scott Boras—to force his employer to void the two remaining option years on his contract and render him a free agent, although the Red Sox never chose to suspend him. They did, however, decide they had had enough of him. So, in a three-way deal completed minutes before the deadline, the Dodgers sent LaRoche and minor league pitcher Bryan Morris to Pittsburgh, which sent All-Star outfielder Jason Bay to Boston, which sent two minor leaguers to the Pirates and one Manny Ramirez to Los Angeles.

That’s when things really got crazy. Ramirez was every bit as fantastic as Jones was not. In 53 regular-season games, Ramirez hit 17 home runs and slugged .743. He reached base in nearly half his at-bats. He was one hit shy of batting .400. He whipped Dodger Stadium crowds and cash registers into delirium. He was nothing less than a dream hitter, providing, by all indications, the single greatest hitting performance by a trade-deadline acquisition ever.

Even so, three weeks after he arrived, the Dodgers went on an eight-game losing streak. Everything else had stopped working. This was worse than meandering—this was a death spiral. The team dropped 41/2 games behind the Diamondbacks, and faced two weekend games in Arizona against two of the best pitchers in the league: Dan Haren and Brandon Webb.

Improbably, in their darkest hour, the Dodgers responded. They won both games, kicking off a stretch in which the team went 18-5. Both young and old contributed, with Andre Ethier and starting pitcher Derek Lowe particularly catching fire. The Diamondbacks, who hadn’t been able to bury the Dodgers when they had the chance, paid for it dearly. When they lost an afternoon game in St. Louis on September 25, they officially handed the NL West to the Dodgers.

That was all well and good, but there was still that matter of a postseason drought to contend with. The 84-78 Dodgers had to face the NL’s top team, the 97–64 Chicago Cubs, in the best-of-five NL Division Series. Los Angeles was a decided underdog, a fate the team seemed destined to fulfill after Lowe, who had an ERA of 0.94 in his final nine regular-season starts, gave up a two-run second-inning home run to Mark DeRosa in the NLDS opener.

But James Loney, facing Cubs starter Ryan Dempster (who was left in the game with two out in the fifth inning even though he had just walked his seventh batter), blasted a grand slam to center field to give the Dodgers a lead they wouldn’t relinquish for the rest of the series. They won 7–2 in Game 1, 10–3 in Game 2, and thanks to a taut performance by 33-year-old Japanese rookie Hiroki Kuroda, 3–1 in Game 3, sending the Dodgers into the best-of-seven NLCS for the first time since ’88.

The Dodgers had been so dominant that they suddenly went from underdogs to favorites in their next matchup, even though they faced a team with a better record, the 92–70 NL East champion Philadelphia Phillies. Vexingly for Los Angeles, the Dodgers led in each of the first four games, but squandered the lead in three of them. Furcal, who had just come back from his long injury absence to excel against the Cubs, threw away a ball in the fifth inning of Game 1, setting the stage for Lowe to give up a two-run home run in what became a 3–2 loss at Philadelphia. Chad Billingsley, so exquisite during the regular season, quickly surrendered a 1-0 lead in Game 2 by allowing eight runs in 22/3 innings. The Dodgers tried to rally, but Blake’s bid for a three-run game-tying home run was caught at the deepest part of the ballpark, and the Phillies held on 8–5.

Returning to Los Angeles, the Dodgers chased Phillies starter Jamie Moyer with six early runs in a 7–2 win behind Kuroda. And leading 5–3 with five outs to go in Game 4, the Dodgers were on the verge of tying the series. But there, the good times ended. Cory Wade and Jonathan Broxton, who between them had allowed three home runs at Dodger Stadium all year, each gave up two-run shots in the top of the eighth, and Philadelphia rallied for a 7–5 victory. Game 5 presented chances for the Dodgers to start one more back-to-the-wall comeback, but they couldn’t take advantage, losing the final game of the series and the season 5–1.

The only Dodgers run of that game came on a home run by Ramirez, who was 13-for-25 with four homers and 11 walks in the playoffs.

As the Dodgers and their fans watched the Phillies defeat a young, spunky Tampa Bay Rays team in the World Series, they could comfort themselves with this. No longer were wins in the postseason an albatross. The Dodgers had made it back to baseball’s Final Four. How soon before they would go farther?

After bringing Ramirez back, it began to seem that the wait would soon be over. The Dodgers raced out to a 21–8 start in 2009, with Ramirez delivering a monster .492 on-base percentage and .641 slugging. But proving that nothing for the Dodgers is ever simple, Ramirez was suspended on May 7 for 50 games for a violation of MLB’s drug policy.

The Dodgers stayed afloat, once again reaching the NLCS for a rematch with the Phillies. And once again, the bullpen failed them. An out away from evening the series at 2–2, Broxton gave up a game-winning double to Philadelphia shortstop Jimmy Rollins, and another Dodger dream died. In the summer of the following year, no longer a fit with the squad, Ramirez was sent away.