“A high fly ball to right field. She is …”

She is heavenly in our memory, still vivid, still true.

She is sailing from the pitcher’s hand toward a man on knotted stilts, all torso and determination and even a little secular prayer, but no legs, none to speak of. His bent front peg trembles, elevating slightly, the rear one already buckling.

She rises so slightly off an invisible cushion of air, then starts to settle, trailing away but not far enough away. The front peg descends under the weight of arms, strong, driving down into the strike zone.

She is inside the circumference of the catcher’s mitt, but the bat intercedes. The arms look horribly awkward, the back elbow bent at almost 90 degrees, the front arm cutting down in front to form a triangle. The back leg elevates at the heel as the batter lunges, almost to the point of falling down.

But she meets flush with the bat, ceasing to be a sphere, transforming into a comet. She is launched by a popgun, a croquet swing. The left wrist twists, then the hand loses the bat entirely. The follow-through whimpers like that of a novice tennis player, but it doesn’t change anything.

He looks up. His back leg comes down again, spread across home plate from his right. His left arm is cocked like a puncher. His first motion out of the batter’s box is of a runner. There’s been a mirage. The living, breathing, conquering athlete was in there all along.

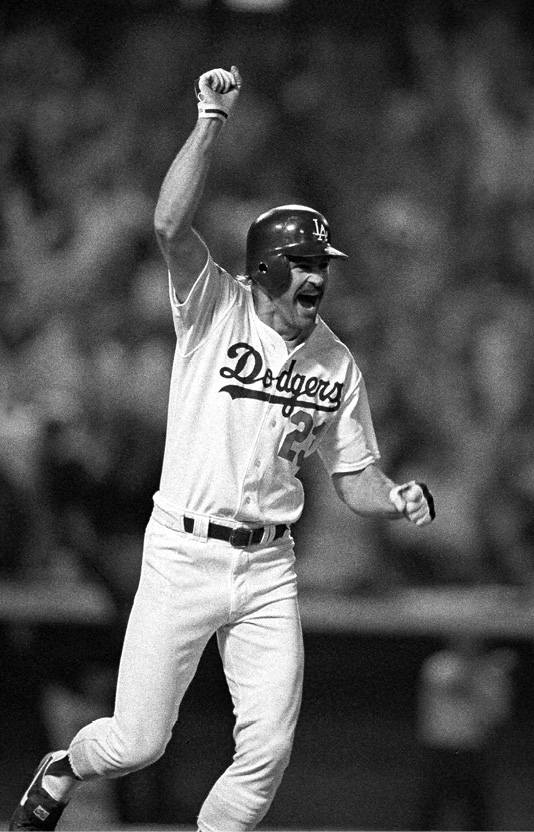

“GONE!” Dodgers pinch-hitter Kirk Gibson rounds the bases in celebration after hitting a game-winning two-run home run in the bottom of the ninth inning to beat the Oakland A’s 5–4 in the first game of the World Series at Dodger Stadium October 15, 1988.

She travels at the speed of light. The right fielder breaks back, taking one, two, three…four…five…six steps, slowing down, his mind and hope retreating before his legs even know. A single set of identical red lights, that’s all, prominently glowing but orphaned, can be seen under the peak of the pavilion roof, behind the brimming, jammed bleacher seats, not abandoned, not at all. Arms are soaring into the air in exultation.

She is crashing down from the sky; mass times acceleration, a shooting star at mission completion. She is in the crowd, she is in our heads, she is in our astonishment, she is in our incredulous joy, she has broken into our ever-loving, unappeasable souls and exploded.

She is …

“GONE!!!”

It had to be something astonishing, something brain-defying. To paraphrase Vin Scully, quoted above making his preeminent call of Kirk Gibson’s pinch-hit, two-run 1988 World Series Game 1-winning home run, it had to be something impossible in a year so improbable.

And in a Series so unbelievable, there was also:

• Mickey Hatcher, a journeyman with 56 hits and one home run all year, bookending the Series with two-run homers in the first innings of Game 1 and Game 5, racing around the bases like the kid we wish all major league players still had inside them.

• Mike Davis, an unadulterated free agent bust for six months, with 55 hits and two home runs after knocking 419 and 65 the previous three seasons, drawing his second walk since September 3 from none other than Dennis Eckersley, who had walked 13 men the entire year—with two out in the ninth inning of Game 1.

• Orel Hershiser, continuing his unprecedented heroics, getting as many hits of his own in Game 2 as he allowed in a 6–0 shutout, then finishing off the A’s in Game 5. For his final 1242/3 innings in 1988, from August 19 through the end of the playoffs, Hershiser had an ERA of 0.65.

• An enfeebled Dodger lineup, including a Game 4 crew with 36 combined home runs in 1988, outshining an Oakland squad bursting with strength. For the series, Jose Canseco (.345 TAv in 1988) and Mark McGwire (.309) combine to go 2-for-36 at the plate with five walks. Canseco hits a second-inning grand slam in Game 1 that should have closed the door on the Dodgers; McGwire wins Game 3 with a ninth-inning homer that should have reopened it for the A’s. Nothing else.

Gibson is done after his Mt. Olympus moment; Hatcher steps in. Mike Marshall goes down with an injury; Davis steps in. John Tudor’s elbow gives way; Tim Leary steps in. Mike Scioscia wrenches his knee after a busted hit-and-run; Rick Dempsey steps in. No matter how hard the wind blew or the ground shook, the pennant never touched the ground.

Baseball is not a sport that embraces upsets. Baseball likes to see the best team win. In the age of the wild card, there’s an undercurrent of dissatisfaction when a lesser team takes advantage of a short series to defeat a greater team. Postseason baseball doesn’t light a candle for Cinderella; it nods to her politely, almost grudgingly, and moves on.

Except for a team like the ’88 Dodgers. When a team wins with such drama and such style, when a team wins with eternal moments, that team can’t be left unacknowledged; they are embraced.

The 1988 World Series title for the Dodgers is one of the greatest in baseball history.

Scioscia’s Swat

Did anyone mention Mike Scioscia? If it weren’t for the onion-shaped Dodger catcher, Kirk Gibson’s remarkable World Series homer never would have happened. Orel Hershiser’s scoreless inning streak would have been the postscript to a disappointing year.

The Dodgers were three outs away from losing their third game of the first four in the 1988 NL Championship Series when, after John Shelby walked, Scioscia no-doubted a Dwight Gooden pitch over the right-field wall, tying the game at 4–4. Scioscia’s blast, as much as anything, set up the remarkable string of events that included a home run by Gibson (a 1-for-16 postseason goat up to that point) in the top of the 12th to give the Dodgers a 5–4 lead and Hershiser’s emergence from the bullpen after pitching 151/3 innings in the previous five days—events that would propel the Dodgers back on track to their last World Series title of the 20th century.

Scioscia hit only three regular-season home runs in 1988 and 68 in 1,441 career games. When he came up to face Gooden in the ninth inning at Shea, Scioscia was 7-for-41 with one walk (.190 on-base percentage), one home run, and two doubles lifetime against Gooden. For his part, Gooden had allowed only one hit since the first inning. Scioscia was not hopeless with the bat: three years earlier, he had an on-base percentage of .407. But as stunned as the Oakland A’s would be by Kirk Gibson’s Game 1 homer six days later, the Mets were almost that floored when Scioscia knocked his out.