Getting there

Located at the heart of Southeast Asia, on the busy aviation corridor between Europe and Australasia, Malaysia and Singapore enjoy excellent international air links. Singapore is served by many more flights than Kuala Lumpur (KL), but can also be slightly more expensive to fly into. Of Malaysia’s regional airports, those in Kota Kinabalu, Kuching and Penang have the most useful international connections, albeit chiefly with other East Asian cities. If you’re heading to Brunei, you’ll most likely have to stop over elsewhere in the region or in the Middle East.

During the peak seasons for travel to Southeast Asia – the Christmas/New Year period, typically from mid-December until early January, and July and August – prices can be fifty percent higher than at other times of year, though you can often avoid the steepest fares by booking well in advance. Fares also rise at weekends and around major local festivals, such as Islamic holidays and the Chinese New Year. Sample fares given here are for round-trip journeys and include taxes and current fuel surcharges. If you’re thinking of visiting on a package trip, note that it’s generally cheaper to book one after you’ve arrived than with a tour operator in your home country.

From the UK and Ireland

London Heathrow has daily nonstop flights to KL with Malaysia Airlines (![]() malaysiaairlines.com), and to Singapore with British Airways (

malaysiaairlines.com), and to Singapore with British Airways (![]() britishairways.com) and Singapore Airlines (

britishairways.com) and Singapore Airlines (![]() singaporeair.com). At the time of writing, the low-cost carrier Norwegian (

singaporeair.com). At the time of writing, the low-cost carrier Norwegian (![]() norwegian.com) had launched a competing nonstop Singapore flight from London Gatwick. From Manchester, Singapore Airlines departs several times a week nonstop to Singapore. On these routes, reckon on the journey time being twelve to thirteen hours. Flying with any other airline or from any other airport in the UK and Ireland involves a change of plane in Europe, the Middle East or elsewhere in Asia. The very best fares to KL or Singapore are around £450/€500 outside high season, with nonstop flights always commanding a premium.

norwegian.com) had launched a competing nonstop Singapore flight from London Gatwick. From Manchester, Singapore Airlines departs several times a week nonstop to Singapore. On these routes, reckon on the journey time being twelve to thirteen hours. Flying with any other airline or from any other airport in the UK and Ireland involves a change of plane in Europe, the Middle East or elsewhere in Asia. The very best fares to KL or Singapore are around £450/€500 outside high season, with nonstop flights always commanding a premium.

From the US and Canada

In most cases the trip from North America, including a stopover, will take at least twenty hours if you fly the transatlantic route from the eastern seaboard, or nineteen hours minimum if you cross the Pacific from the west coast. It is, however, possible to fly nonstop from San Francisco to Singapore on Singapore Airlines (![]() singaporeair.com), and from Los Angeles to Singapore on United (

singaporeair.com), and from Los Angeles to Singapore on United (![]() united.com), with trips lasting around seventeen hours. From Honolulu, there’s also the option of flying with Scoot (

united.com), with trips lasting around seventeen hours. From Honolulu, there’s also the option of flying with Scoot (![]() flyscoot.com), Singapore Airlines’ low-cost-arm, to Singapore.

flyscoot.com), Singapore Airlines’ low-cost-arm, to Singapore.

The quickest route isn’t always the cheapest: it can sometimes cost less to fly westwards from the east coast, stopping off in Northeast Asia en route. Fares start at around US$800 or Can$1100 for flights from major US or Canadian airports on either coast.

Plenty of airlines operate to East Asia from major North American cities. If your target is Borneo, it’s worth investigating connecting with one of the east Asian airlines – Kota Kinabalu, for example, has flights from Hong Kong, Shanghai and Seoul.

From Australia and New Zealand

Geographical proximity means there’s a good range of flights from Australia and New Zealand into Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei, including a useful link between Melbourne and Borneo with Royal Brunei Airlines (![]() flyroyalbrunei.com). Budget flights include services from Australia to KL with AirAsia (

flyroyalbrunei.com). Budget flights include services from Australia to KL with AirAsia (![]() airasia.com) and Malindo Air (

airasia.com) and Malindo Air (![]() malindoair.com), and to Singapore with Jetstar (

malindoair.com), and to Singapore with Jetstar (![]() jetstar.com) and Scoot (

jetstar.com) and Scoot (![]() flyscoot.com), and from Christchurch in New Zealand to KL (AirAsia) and Singapore (Jetstar).

flyscoot.com), and from Christchurch in New Zealand to KL (AirAsia) and Singapore (Jetstar).

If you’re flying from, say, Perth to Singapore or KL, expect fares to start at as little as Aus$450 return in low season, while Melbourne to Singapore will set you back at least Aus$550. Christchurch to KL or Singapore generally starts at NZ$1000 return.

From South Africa

The quickest way to reach Malaysia or Singapore from South Africa is to fly with Singapore Airlines (![]() singaporeair.com), which offers nonstop flights to Singapore from Cape Town (11hr) via Johannesburg; reckon on ten hours’ flying time. That said, it’s often cheaper to book a ticket that involves changing planes en route, usually in the Middle East. If you’re lucky you may land a fare of around R8000 return, including taxes, though it’s not uncommon to have to pay R1000–2000 more.

singaporeair.com), which offers nonstop flights to Singapore from Cape Town (11hr) via Johannesburg; reckon on ten hours’ flying time. That said, it’s often cheaper to book a ticket that involves changing planes en route, usually in the Middle East. If you’re lucky you may land a fare of around R8000 return, including taxes, though it’s not uncommon to have to pay R1000–2000 more.

From elsewhere in Southeast Asia

Budget airlines make it easy to explore Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei as part of a wider trip through Southeast Asia. The most useful no-frills carriers for the three countries covered in this book are Malaysia’s AirAsia (![]() airasia.com), Firefly (

airasia.com), Firefly (![]() fireflyz.com.my) and Malindo Air (

fireflyz.com.my) and Malindo Air (![]() malindoair.com), and Singapore’s Scoot (

malindoair.com), and Singapore’s Scoot (![]() flyscoot.com) and Jetstar Asia (

flyscoot.com) and Jetstar Asia (![]() jetstar.com). Though fuel surcharges and taxes do take some of the shine off the fares, prices can still be good, especially if you book well in advance.

jetstar.com). Though fuel surcharges and taxes do take some of the shine off the fares, prices can still be good, especially if you book well in advance.

You can, of course, reach Malaysia or Singapore from their immediate neighbours by means other than flying. There are road connections from Thailand and from Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo); ferries from Indonesia and from the southern Philippines, and trains from Thailand. Below is a round-up of the most popular routes.

The Eastern & Oriental Express

Unlike some luxury trains in other parts of the world, the Eastern & Oriental Express (![]() belmond.com) isn’t a re-creation of a classic colonial-era rail journey, but a sort of fantasy realization of how such a service might have looked had it existed in Southeast Asia. Employing 1970s Japanese rolling stock, given an elegant old-world cladding with wooden inlay work and featuring Thai and Malay motifs, the train travels between Bangkok and Singapore, with the option of starting or ending the trip in KL, at least monthly. En route there are extended stops at Kanchanaburi for a visit to the infamous bridge over the River Kwai, and at Kuala Kangsar. An observation deck at the rear of the train makes the most of the passing scenery. The trip doesn’t come cheap, of course: the two-night Bangkok–KL segment costs around £2000/US$2600 per person in swish, en-suite Pullman accommodation, including meals – and alcohol costs extra.

belmond.com) isn’t a re-creation of a classic colonial-era rail journey, but a sort of fantasy realization of how such a service might have looked had it existed in Southeast Asia. Employing 1970s Japanese rolling stock, given an elegant old-world cladding with wooden inlay work and featuring Thai and Malay motifs, the train travels between Bangkok and Singapore, with the option of starting or ending the trip in KL, at least monthly. En route there are extended stops at Kanchanaburi for a visit to the infamous bridge over the River Kwai, and at Kuala Kangsar. An observation deck at the rear of the train makes the most of the passing scenery. The trip doesn’t come cheap, of course: the two-night Bangkok–KL segment costs around £2000/US$2600 per person in swish, en-suite Pullman accommodation, including meals – and alcohol costs extra.

From Thailand

A daily Special Express train service leaves Hualamphong station in Bangkok at 3.10pm on the 1000km journey south to the Malaysian border town of Padang Besar, where travellers can change for Malaysian ETS trains on the west-coast line. The train calls at (among others) Hua Hin, Surat Thani and Hat Yai before reaching Padang Besar at 9am Thai time (10am Malaysian time). Also useful is the Thai rail service from Hat Yai across to Sungai Golok on the east coast of the Kra isthmus, close to the Malaysian border crossing at Rantau Panjang, from where buses run to Kota Bharu.

As regards flights, plenty of services connect Bangkok, Chiang Mai and Thai resorts with Malaysian airports and Singapore. Some are run by the low-cost airlines, while others are provided by Bangkok Airways (![]() bangkokair.com) and Singapore Airlines subsidiary SilkAir (

bangkokair.com) and Singapore Airlines subsidiary SilkAir (![]() silkair.com).

silkair.com).

A few scheduled ferry services sail from the most southwesterly Thai town of Satun to the Malaysian west-coast town of Kuala Perlis (30min) and to the island of Langkawi (1hr 30min). If you’re departing from Thailand by sea for Malaysia, ensure your passport is stamped at the immigration office at the pier to avoid problems with the Malaysian immigration officials when you arrive. Another option is the ferry from the southern Thai town of Ban Taba to the Malaysian town of Pengkalan Kubor, where frequent buses run to Kota Bharu, 20km away. Buses connect Ban Taba with the provincial capital, Narathiwat (1hr 30min).

The easiest road access from Thailand is via Hat Yai, from where buses, minivans and a few shared taxis run to Butterworth (4hr) and nearby George Town on Penang Island, with some buses continuing right to KL or Singapore. From the interior Thai town of Betong, there’s a road across the border to the Malaysian town of Pengkalan Hulu, from where Route 67 leads west to Sungai Petani; share taxis serve the route. You can also get a taxi from Ban Taba for the few kilometres south to Kota Bharu.

From Indonesia

Plenty of flights, including many operated by the low-cost airlines, connect major airports in Java and Sumatra, plus Bali and Lombok, with Malaysia and Singapore. There’s also a service between Manado in Sulawesi and Singapore with Singapore Airlines’ subsidiary SilkAir (![]() silkair.com). As for Kalimantan, AirAsia (

silkair.com). As for Kalimantan, AirAsia (![]() airasia.com) operates between Balikpapan and KL, and Malaysia Airlines’ subsidiary MASwings (

airasia.com) operates between Balikpapan and KL, and Malaysia Airlines’ subsidiary MASwings (![]() maswings.com.my) operates between Pontianak and Kuching, and also between Tarakan and Tawau in southeastern Sabah.

maswings.com.my) operates between Pontianak and Kuching, and also between Tarakan and Tawau in southeastern Sabah.

It’s possible to reach Sarawak from Kalimantan on just one road route, through the western border town of Entikong and onwards to Kuching. The bus trip from the western city of Pontianak to Entikong takes seven hours, crossing to the Sarawak border town of Tebedu; stay on the same bus for another three hours to reach Kuching.

As for ferries, Dumai, on the east coast of Sumatra, has a daily service to Melaka (2hr), with more sailings from Dumai and Tanjong Balai further south to Port Klang near Kuala Lumpur (3hr). There are also a few services from Bintan and Batam islands in the Riau archipelago (accessible by plane or boat from Sumatra or Jakarta) to Johor Bahru (30min) or Singapore (30min), and there’s a minor ferry crossing from Tanjung Balai to Kukup (1hr), just southwest of Johor Bahru. Over in Borneo, ferries connect Tawau in Sabah with Nunakan (1hr) and Tarakan (3hr).

Addresses and place names

Place names in Malaysia present something of a linguistic dilemma. Road signage is often in Malay only, and some colonial-era names have been deliberately changed to Malay ones, but since English is widely used in much of the country, local people are just as likely to say “Kinta River” as “Sungai Kinta”, or talk of “Northam Road” in George Town rather than “Jalan Sultan Ahmad Shah”, and so on. The Guide mostly uses English-language names, for simplicity. The Glossary includes Malay terms for geographical features like beaches, mountains and so forth.

From the Philippines

A weekly ferry service operates between Zamboanga in the southern Philippines and Sandakan in Sabah, and Philippine budget airline Cebu Pacific (![]() cebupacificair.com) was considering launching a flight on the same route at the time of writing. Other low-cost flights include from Clark to KL and Kota Kinabalu (both AirAsia;

cebupacificair.com) was considering launching a flight on the same route at the time of writing. Other low-cost flights include from Clark to KL and Kota Kinabalu (both AirAsia; ![]() airasia.com), from Clark and Manila to Singapore (JetStar Asia;

airasia.com), from Clark and Manila to Singapore (JetStar Asia; ![]() jetstar.com), and from Boracay and Cebu to Singapore (Scoot;

jetstar.com), and from Boracay and Cebu to Singapore (Scoot; ![]() flyscoot.com). Full-cost airlines provide additional links, including Manila to Bandar Seri Begawan (Royal Brunei Airlines;

flyscoot.com). Full-cost airlines provide additional links, including Manila to Bandar Seri Begawan (Royal Brunei Airlines; ![]() flyroyalbrunei.com).

flyroyalbrunei.com).

Travel agents and tour operators

Adventure Alternative UK ![]() 028 7083 1258,

028 7083 1258, ![]() adventurealternative.com. A superb range of off-the-beaten track Borneo tours.

adventurealternative.com. A superb range of off-the-beaten track Borneo tours.

Adventure World Australia ![]() 1300 295049,

1300 295049, ![]() adventureworld.com.au; New Zealand

adventureworld.com.au; New Zealand ![]() 0800 238368,

0800 238368, ![]() adventureworld.co.nz. Short Malaysia tours, covering cities and some wildlife areas.

adventureworld.co.nz. Short Malaysia tours, covering cities and some wildlife areas.

Allways Dive Expedition Australia ![]() 1800 338239,

1800 338239, ![]() allwaysdive.com.au. Dive holidays to the prime dive sites of Sabah.

allwaysdive.com.au. Dive holidays to the prime dive sites of Sabah.

Asia Classic Tours US ![]() 1800 717 7752,

1800 717 7752, ![]() asiaclassictours.com. Malaysia tours, lasting ten days or more, taking in various parts of the country and sometimes Singapore, too.

asiaclassictours.com. Malaysia tours, lasting ten days or more, taking in various parts of the country and sometimes Singapore, too.

Audley Travel US & Canada ![]() 1855 838 2120, UK

1855 838 2120, UK ![]() 01993 838000, Ireland

01993 838000, Ireland ![]() 1800 992198,

1800 992198, ![]() audleytravel.com. Luxury tours concentrating on East Malaysia.

audleytravel.com. Luxury tours concentrating on East Malaysia.

Bestway Tours US & Canada ![]() 1800 663 0844,

1800 663 0844, ![]() bestway.com. A handful of cultural and wildlife tours featuring East Malaysia and Brunei, plus the peninsula and Singapore.

bestway.com. A handful of cultural and wildlife tours featuring East Malaysia and Brunei, plus the peninsula and Singapore.

Borneo Tour Specialists Australia ![]() 07 3221 5777,

07 3221 5777, ![]() borneo.com.au. Small-group, customizable tours of all of Borneo, covering wildlife, trekking and tribal culture.

borneo.com.au. Small-group, customizable tours of all of Borneo, covering wildlife, trekking and tribal culture.

Dive Adventures Australia ![]() 1300 657420,

1300 657420, ![]() diveadventures.com.au. Sabah and Labuan dive packages.

diveadventures.com.au. Sabah and Labuan dive packages.

Eastravel UK ![]() 01473 214305,

01473 214305, ![]() eastravel.co.uk. Bespoke Malaysia trips.

eastravel.co.uk. Bespoke Malaysia trips.

Exodus Travels US ![]() 1844 227 9087, UK

1844 227 9087, UK ![]() 020 3553 6240,

020 3553 6240, ![]() adventurecenter.com. Several packages, mainly focused on East Malaysia, plus tailor-made trips.

adventurecenter.com. Several packages, mainly focused on East Malaysia, plus tailor-made trips.

Explore UK ![]() 01252 883618,

01252 883618, ![]() explore.co.uk. A handful of Malaysia tours.

explore.co.uk. A handful of Malaysia tours.

Explorient US ![]() 1800 785 1233,

1800 785 1233, ![]() explorient.com. Malaysia and Singapore packages, including both city and jungle breaks.

explorient.com. Malaysia and Singapore packages, including both city and jungle breaks.

Intrepid Travel US ![]() 1800 970 7299, Canada

1800 970 7299, Canada ![]() 1855 299 1211, UK

1855 299 1211, UK ![]() 0808 274 5111, Australia

0808 274 5111, Australia ![]() 1300 854500, New Zealand

1300 854500, New Zealand ![]() 0800 600 610;

0800 600 610; ![]() intrepidtravel.com. Several Malaysia offerings, mainly focused on Borneo or taking in Thailand and Singapore as well.

intrepidtravel.com. Several Malaysia offerings, mainly focused on Borneo or taking in Thailand and Singapore as well.

Jade Tours Canada ![]() 1800 387 0387,

1800 387 0387, ![]() jadetours.com. Borneo and Peninsular Malaysia trips.

jadetours.com. Borneo and Peninsular Malaysia trips.

Lee’s Travel UK ![]() 0800 811 9888,

0800 811 9888, ![]() leestravel.com. Far Eastern flight deals, including discounted Malaysia and Singapore Airlines tickets.

leestravel.com. Far Eastern flight deals, including discounted Malaysia and Singapore Airlines tickets.

Namaste Travel UK ![]() 020 7725 6765,

020 7725 6765, ![]() namaste.travel. Half a dozen varied Malaysia packages.

namaste.travel. Half a dozen varied Malaysia packages.

Pentravel South Africa ![]() 087 231 2000,

087 231 2000, ![]() pentravel.co.za. Flight deals plus city breaks that combine Singapore with Bangkok or Hong Kong.

pentravel.co.za. Flight deals plus city breaks that combine Singapore with Bangkok or Hong Kong.

Peregrine Adventures US ![]() 1855 832 4859, UK

1855 832 4859, UK ![]() 020 7408 9021, Australia

020 7408 9021, Australia ![]() 1300 854455;

1300 854455; ![]() peregrineadventures.com. Experienced operator with a handful of East Malaysia packages.

peregrineadventures.com. Experienced operator with a handful of East Malaysia packages.

Premier Holidays UK ![]() 0844 493 7531,

0844 493 7531, ![]() premierholidays.co.uk. Tours of East Malaysia, plus holidays in Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore.

premierholidays.co.uk. Tours of East Malaysia, plus holidays in Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore.

Reef & Rainforest US ![]() 1800 794 9767,

1800 794 9767, ![]() reefrainforest.com. Sabah dive packages based in resorts or a liveaboard.

reefrainforest.com. Sabah dive packages based in resorts or a liveaboard.

Rex Air UK ![]() 020 7439 1898,

020 7439 1898, ![]() rexair.co.uk. Specialist in discounted flights to the Far East, with a few package tours to boot.

rexair.co.uk. Specialist in discounted flights to the Far East, with a few package tours to boot.

Sayang Holidays US ![]() 1888 472 9264,

1888 472 9264, ![]() sayangholidays.com. City- or resort-based Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore tours, plus Borneo.

sayangholidays.com. City- or resort-based Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore tours, plus Borneo.

STA Travel US ![]() 1800 781 4040,

1800 781 4040, ![]() statravel.com; UK

statravel.com; UK ![]() 0333 321 0099,

0333 321 0099, ![]() statravel.co.uk; Australia

statravel.co.uk; Australia ![]() 134782,

134782, ![]() statravel.com.au; New Zealand

statravel.com.au; New Zealand ![]() 0800 474400,

0800 474400, ![]() statravel.co.nz; South Africa

statravel.co.nz; South Africa ![]() 0861 781781,

0861 781781, ![]() statravel.co.za. Worldwide specialists in low-cost flights for students and under-26s; other customers also welcome.

statravel.co.za. Worldwide specialists in low-cost flights for students and under-26s; other customers also welcome.

Symbiosis UK ![]() 0845 123 2844,

0845 123 2844, ![]() symbiosis-travel.com. Diving, trekking and longhouse stays in various Malaysian locations.

symbiosis-travel.com. Diving, trekking and longhouse stays in various Malaysian locations.

Tour East Canada ![]() 1877 578 8888,

1877 578 8888, ![]() toureast.com. A couple of excursions throughout Malaysia, with the option of taking in Singapore, too.

toureast.com. A couple of excursions throughout Malaysia, with the option of taking in Singapore, too.

Trailfinders UK ![]() 020 7368 1200,

020 7368 1200, ![]() trailfinders.com; Ireland

trailfinders.com; Ireland ![]() 01 677 7888,

01 677 7888, ![]() trailfinders.ie. Flights and a few tours, including major Malaysian cities, Borneo and Singapore.

trailfinders.ie. Flights and a few tours, including major Malaysian cities, Borneo and Singapore.

Travel Masters US ![]() 512 323 6961,

512 323 6961, ![]() travel-masters.net. Dive packages at Sipadan, Mabul and Kapalai in Sabah.

travel-masters.net. Dive packages at Sipadan, Mabul and Kapalai in Sabah.

USIT Ireland ![]() 01 602 1906,

01 602 1906, ![]() usit.ie. Student and youth travel.

usit.ie. Student and youth travel.

Visas and entry requirements

Nationals of the UK, Ireland, US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa do not need visas in advance to stay in Malaysia, Singapore or Brunei, and it’s easy to extend your permission to stay.

That said, check with the relevant embassy or consulate, as the rules on visas are complex and subject to change. Ensure that your passport is valid for at least six months from the date of your trip, and has several blank pages for entry stamps.

Malaysia

Upon arrival in Malaysia, citizens of Australia, Canada, the UK, Ireland, US, New Zealand and South Africa receive a passport stamp entitling them to a ninety-day stay. Visitors who enter via Sarawak, however, receive a thirty-day stamp.

It’s straightforward to extend your permit through the Immigration Department, who have offices (listed in the Guide) in Kuala Lumpur and major towns; you can also find details of visa requirements for various nationalities on their website, ![]() www.imi.gov.my. Visitors from the aforementioned countries can also cross into Singapore or Thailand and back to be granted a fresh Malaysia entry stamp.

www.imi.gov.my. Visitors from the aforementioned countries can also cross into Singapore or Thailand and back to be granted a fresh Malaysia entry stamp.

Tourists travelling from the Peninsula to East Malaysia (Sarawak and Sabah) must be cleared again by immigration. Visitors to Sabah can remain as long as their original entry stamp is valid, but Sarawak maintains its own border controls – a condition of its joining the Federation in 1965 – which means you are always stamped in and given a thirty-day Sarawak visa even when arriving from other parts of Malaysia. For a full list of Malaysia’s embassies and consulates, see ![]() kln.gov.my.

kln.gov.my.

Malaysia embassies and consulates

Australia 7 Perth Ave, Yarralumla, Canberra ![]() 02 6120 0300.

02 6120 0300.

Brunei 61, Junction 336, Jalan Duta, Bandar Seri Begawan ![]() 02 381095.

02 381095.

Canada 60 Boteler St, Ottawa ![]() 613 241 5182.

613 241 5182.

Indonesia Jalan H.R. Rasuna Said, Kav. X/6, No. 1–3 Kuningan, Jakarta South ![]() 021 522 4947.

021 522 4947.

Ireland Shelbourne House, Level 3A–5A, Shelbourne Rd, Ballsbridge, Dublin ![]() 01 667 7280.

01 667 7280.

New Zealand 10 Washington Ave, Brooklyn, PO Box 9422, Wellington ![]() 04 385 2439.

04 385 2439.

Singapore 301 Jervois Rd ![]() 6235 0111.

6235 0111.

South Africa 1007 Francis Baard St, Arcadia, Pretoria 0083 ![]() 012 342 5990.

012 342 5990.

Thailand 33–35 South Sathorn Rd, Bangkok 10120 ![]() 02 629 6800.

02 629 6800.

UK 52 Bedford Row, London ![]() 020 7242 4308.

020 7242 4308.

US 3516 International Court, NW Washington DC ![]() 202 572 9700.

202 572 9700.

Drugs: a warning

In Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei, the possession of illegal drugs – hard or soft – carries a hefty prison sentence or even the death penalty. If you are arrested for drugs offences you can expect no mercy from the authorities and little help from your consular representatives. The simple advice, therefore, is not to have anything whatsoever to do with drugs in any of these countries. Never agree to carry anything through customs for a third party.

Singapore

Singapore reserves the term “visa” for permits that must be obtained in advance. Travellers from many countries, however, are granted a visit pass on arrival. Although the duration of the pass can vary at the discretion of immigration officials, citizens of the UK, Ireland, US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa are usually given at least thirty days. There is a formal procedure for extending it, but it’s usually much easier to simply do a day-trip by a bus to Johor Bahru just inside Malaysia and be given a fresh pass on returning to Singapore.

For details of nationalities that require visas, along with how to apply and how to extend a visit pass, see ![]() ica.gov.sg. Full details of Singapore’s embassies abroad are at

ica.gov.sg. Full details of Singapore’s embassies abroad are at ![]() mfa.gov.sg.

mfa.gov.sg.

Singapore embassies and consulates

Australia 17 Forster Crescent, Yarralumla, Canberra, ACT 2600 ![]() 02 6271 2000.

02 6271 2000.

Brunei 8 Junction 74, Jalan Subok, Bandar Seri Begawan ![]() 02 262741.

02 262741.

Indonesia Block X/4 Kav No. 2, Jalan H.R. Rasuna Said, Kuningan, Jakarta South ![]() 021 2995 0400.

021 2995 0400.

Ireland 2 Ely Place Upper, Dublin ![]() 01 669 1700.

01 669 1700.

Malaysia 209 Jalan Tun Razak, Kuala Lumpur ![]() 03 2164 1013.

03 2164 1013.

New Zealand 17 Kabul St, Khandallah, Wellington ![]() 04 470 0850.

04 470 0850.

South Africa 980–982 Francis Baard St, Pretoria ![]() 012 430 6035.

012 430 6035.

Thailand 129 South Sathorn Rd, Bangkok 10120 ![]() 02 348 6700.

02 348 6700.

UK 9 Wilton Crescent, Belgravia, London ![]() 020 7235 8315.

020 7235 8315.

US 3501 International Place NW, Washington DC ![]() 202 537 3100.

202 537 3100.

Brunei

UK and US nationals are allowed to stay in Brunei for up to ninety days on arrival; Australian and New Zealand passport holders are granted thirty days; and Canadians get fourteen days. South African citizens need to apply for a visa in advance. Once in Brunei, extending your permission to stay is usually a formality; apply at the Immigration Department in Bandar Seri Begawan. For full details of Brunei’s embassies, see ![]() mofat.gov.bn.

mofat.gov.bn.

Brunei embassies and consulates

Australia 10 Beale Crescent, Deakin, Canberra ![]() 02 6285 4500.

02 6285 4500.

Canada 395 Laurier Ave East, Ottawa ![]() 613 864 5654.

613 864 5654.

Indonesia 3 & 5 Jalan Patra Kuningan 9, Jakarta South ![]() 021 2911 0242.

021 2911 0242.

Malaysia 2 Jalan Diplomatik 2/5, Putrajaya ![]() 03 8888 7777.

03 8888 7777.

Singapore 325 Tanglin Rd ![]() 6733 9055.

6733 9055.

South Africa c/o the embassy in Singapore.

Thailand 12 Soi Ekamai 2, 63 Sukhumvit Rd, Bangkok ![]() 02 714 7395.

02 714 7395.

UK 19–20 Belgrave Square, London ![]() 020 7581 0521.

020 7581 0521.

US 3520 International Court NW, Washington DC ![]() 202 237 1838.

202 237 1838.

Customs allowances

Malaysia’s duty-free allowances are 200 cigarettes or 225g of tobacco, and one litre of wine, spirits or liquor. Entering Singapore from anywhere other than Malaysia (with which there are no duty-free allowances), you can bring in up to three litres of alcohol duty-free; duty is payable on all tobacco.

Visitors to Brunei may bring in 200 cigarettes, 50 cigars or 250g of tobacco, and 60ml of perfume; non-Muslims over seventeen can also import two bottles of liquor and twelve cans of beer for personal consumption (any alcohol brought into the country must be declared upon arrival).

Getting around

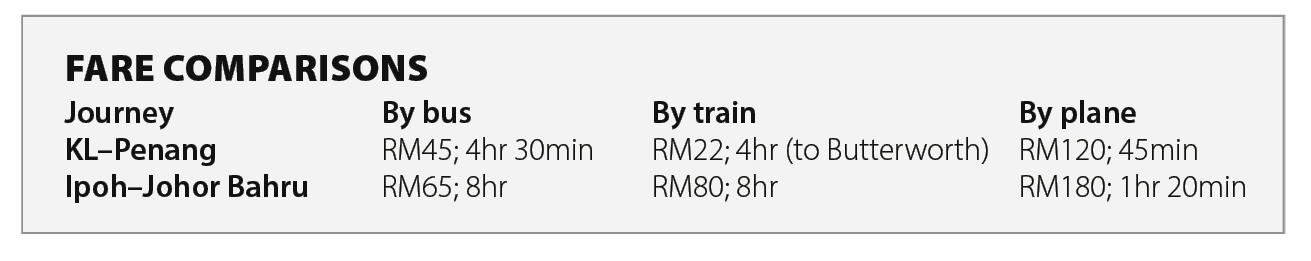

Public transport in Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei is reliable and inexpensive. Much of your travelling, particularly in Malaysia, will be by bus, minivan or, occasionally, long-distance shared taxi. Budget flights are a good option for hopping around the region, especially given that no ferries connect Peninsular and East Malaysia. The Peninsula’s rail system is now partly upgraded, slashing journey times.

Sabah and Sarawak have their own travel peculiarities – in parts of Sarawak, for instance, you’re reliant on boats or light aircraft. The chapters on Sarawak, Sabah, Brunei and Singapore contain specific information on their transport systems; the focus in this section is largely on Peninsular Malaysia.

The transport system is subject to heavy pressure during any nationwide public holiday – particularly Muslim festivals, the Chinese New Year, Deepavali, Christmas and New Year. A day or two before each festival, whole communities embark upon balik kampung, which literally means a return to the village (or hometown) to be with family. It’s worth buying tickets at least one week in advance to travel at these times; if you’re driving, steel yourself for more than the usual number of jams.

And finally, bear in mind that chartering transport – longboats, or cars with drivers – to reach some off-the-beaten-track national park or island is always pricey for what it is.

By bus

Malaysia’s bus network is fairly comprehensive, at least in terms of serving major cities and towns. However, buses rarely stray off main roads to reach rural sites of the kind that tourists might want to get to – nature reserves, caves, hill resorts and so forth. In such instances, the best you can do is to ask the driver if you can get off at the start of the turning for your destination, after which you’re left to your own devices.

Bus companies

A handful of well-established bus companies give reliable service in Peninsular Malaysia. The largest is Transnasional (![]() transnasional.com.my) and its slightly pricier subsidiary Plusliner (

transnasional.com.my) and its slightly pricier subsidiary Plusliner (![]() plusliner.com.my), whose services have the entire Peninsula pretty well covered. Among many competitors are Sri Maju (

plusliner.com.my), whose services have the entire Peninsula pretty well covered. Among many competitors are Sri Maju (![]() srimaju.com) and Konsortium Bas Ekspres (

srimaju.com) and Konsortium Bas Ekspres (![]() kbes.com.my), both strong on the west coast.

kbes.com.my), both strong on the west coast.

Long-distance (express) buses

The long-distance bus network borders on the anarchic: a largish town can be served by a dozen or more express bus companies. Timetabling is a mess, too: every bus station has signs above a zillion ticket booths displaying a zillion routes and departure times, but these may be out of date, as may even the websites of the biggest bus companies. Given this, the route details in this Guide are a general indication of what you can expect; for specifics, you will need to call the bus company’s local office (stations do not have central enquiry numbers) or ask in person.

At least the plethora of companies means you can often find tickets at the station for a bus heading to your destination within the next two hours. However, it can be worth booking a day in advance for specific departures or on routes where services are limited (in between, rather than along, the west and east coasts for example). Online booking is possible, either on the websites of the biggest operators or on recently launched umbrella websites (such as ![]() easybook.com) representing multiple firms, but there is nothing as reliable as buying a ticket at the bus station itself.

easybook.com) representing multiple firms, but there is nothing as reliable as buying a ticket at the bus station itself.

Most intercity buses are comfortable, with air conditioning and curtains to screen out the blazing sun, though seats can be tightly packed. There are rarely toilets on board, but longer journeys feature a rest stop every couple of hours, with a short meal stopover if needed. On a few plum routes, notably KL–Singapore and KL–Penang, additional luxury or “executive” coaches charge up to twice the regular fares and offer plush seats, greater legroom plus on-board movies.

Local buses

In addition to express buses, the Peninsula has a network of simple, somewhat sporadic local buses serving small towns on routes that can stretch up to 100km end to end. Local buses are organized at the state level, and this means that many services do not cross into adjacent states even when the same firm is active on both sides of the border. Tickets, usually bought on board from the driver or conductor, cost a few ringgit, reaching RM10 only on the longest routes. Note that services typically run only during daylight hours, winding down by 8pm if not earlier.

By train

For years, Malaysian trains were a laughing stock – antiquated and generally much slower than buses. Now, after belated investment, the trains are once again a competitive option in parts of the country, and even bigger changes are in the pipeline, with plans to build a high-speed rail link between Kuala Lumpur and Singapore by the mid-2020s as well as a new, metro-like shuttle service between Johor Bahru and Singapore.

The Peninsula’s rail service is operated by KTM (short for Keretapi Tanah Melayu, literally “Trains of the Malay Land”; ![]() 03 2267 1200,

03 2267 1200, ![]() ktmb.com.my). Its network is shaped roughly like a Y, with the southern end anchored at Johor Bahru and the intersection, for historical reasons, at the small town of Gemas. The northwest branch links up with Thai track at the border town of Padang Besar via KL, Ipoh and Alor Setar; the northeast branch cuts up through the interior to terminate at Tumpat, beyond Kota Bharu on the east coast. KTM also runs a useful Komuter rail service in the Kuala Lumpur area and the northwest.

ktmb.com.my). Its network is shaped roughly like a Y, with the southern end anchored at Johor Bahru and the intersection, for historical reasons, at the small town of Gemas. The northwest branch links up with Thai track at the border town of Padang Besar via KL, Ipoh and Alor Setar; the northeast branch cuts up through the interior to terminate at Tumpat, beyond Kota Bharu on the east coast. KTM also runs a useful Komuter rail service in the Kuala Lumpur area and the northwest.

Trains are at their best on the west-coast line, which is electrified and double-tracked right from Gemas up to Padang Besar, enabling the modern, fast (and thus much in demand) Electric Train Service (ETS) to run. The fly in the ointment is that although there were at least a dozen services north of KL daily at the time of research, services between KL and Gemas were still sparse. The ETS should eventually be extended all the way to Johor Bahru, possibly by 2020.

Intercity (Antarabandar) services make up the rest of the network, between Johor Bahru and the east via the interior. These remain backward and single-tracked, meaning a handful of slow, often basic, trains run in one direction each day – journeys can be mind-numbing and are often delayed. Even so, trains can still be the quickest way to reach some settlements here, and the Jungle Railway stretch is also entertaining in parts. Unfortunately, there were no direct services between KL and the east coast at the time of research, although these may return in the near future; in the meantime, passengers from KL and the west coast need to change at Gemas for the east-coast line.

Seats and fares

ETS trains have no seat classes, but fares still vary depending on whether you travel on a “platinum” (faster, with fewer stops) or “gold” service; KL to Butterworth, for example, costs around RM80 in platinum (4hr), RM60 in gold (4hr 30min). On intercity trains, seats theoretically divide into premier (first), superior (second) and economy (third) class, although not all trains feature all three; sleeper services are limited to the overnight trains between Johor Bahru and Tumpat, and are also split into three theoretical classes. As an indication of fares, a seat from Johor Bahru all the way to Wakaf Bharu (near Kota Bharu) costs RM45, a sleeper berth just a few ringgit more.

Tickets and timetables

You can buy tickets at stations via KTM’s website or their KTMB MobTicket app; for ETS trains, it’s best to book at least a couple of days in advance.

Note that as KTM is continually upgrading and maintaining its lines, it has made frequent, often radical changes to its timetables and routes over the past few years – it’s a good idea to check the latest details on the company’s website before you travel.

By long-distance taxi

Long-distance taxis are fading away somewhat, but still run between some cities and towns, and are especially useful in Sabah. They can be a lot quicker than buses, but the snag is that they operate on a shared basis, so you have to wait for enough people to show up to fill the vehicle. In practice, you’re unlikely to make much use of them unless you’re travelling in a group or you want to travel to a destination that’s off the beaten track. Fares usually work out at double the corresponding bus fare; official prices are usually chalked up on a board at the taxi rank or listed on a laminated tariff card (senarai tambang), which you can ask to see.

Some taxi operators assume any tourist who shows up will want to charter a taxi; if you want to use the taxi on a shared basis, say “nak kongsi dengan orang lain”.

Kereta sapu and minivans

In rural areas of Malaysia, notably in East Malaysia, private cars, minivans and (on rough roads) four-wheel-drives fill in handily for the lack of buses along certain routes. Sometimes called kereta sapu in Malay, or “taxis” as a shorthand, they may not be as ad hoc as they sound, even running at fixed times each day in some places.

Minivans also operate on a more formal level: travel agencies run them to take backpackers to destinations such as the Perhentians and Taman Negara, or just across the border to Hat Yai in Thailand.

By ferry or boat

Regular ferries serve all the major islands, from Penang to Labuan off the coast of Sabah. Within Sarawak, there are scheduled boat services between Kuching and Sibu and up the Rejang River to Belaga. Vessels tend to be narrow, cramped affairs – imagine being inside an aircraft, only on water – and some may be no more than speedboats or motorized penambang (fishing craft). It’s best to book in advance when there are only a few sailings each day; otherwise, just turn up and buy tickets at the jetty. Boat travel also often comes into play in national parks and in a few rural areas, where you may need to charter one to travel between coastal beaches or to reach remote upriver villages. Details are given in the text of the Guide where relevant.

By plane

It’s easy to fly within Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei. Most state capitals have airports (though some have only one or two flights a day), and there are also regional airports at Langkawi, Labuan, Redang and Tioman islands, and scattered around Sabah and Sarawak – for example, at Mulu for Mulu National Park. You can fly either with the established national airlines or with a variety of low-cost operators, though there may be little to choose between them pricewise if you book late.

Fares can be remarkably cheap, especially for early-morning or late-night departures, or when booked some way in advance. The ninety-minute flight from KL to Kuching, for example, can cost as little as RM100 one way including tax with a budget airline, though two or three times that is more typical. Note also that any trip involving Singapore or Brunei will be more expensive than the distance might suggest, as it will count as an international flight.

Domestic airlines and routes

AirAsia ![]() airasia.com. The airline that pioneered the local low-cost market offers a comprehensive service throughout Malaysia and also serves Singapore and Brunei.

airasia.com. The airline that pioneered the local low-cost market offers a comprehensive service throughout Malaysia and also serves Singapore and Brunei.

Firefly ![]() fireflyz.com.my. Malaysia Airlines’ discount subsidiary has some useful flights out of KL’s Subang airport, Penang and Ipoh, serving other Peninsula cities and Singapore.

fireflyz.com.my. Malaysia Airlines’ discount subsidiary has some useful flights out of KL’s Subang airport, Penang and Ipoh, serving other Peninsula cities and Singapore.

Jetstar Asia ![]() jetstar.com. Budget flights from Singapore to KL and Penang.

jetstar.com. Budget flights from Singapore to KL and Penang.

Malindo Air ![]() malindoair.com. Part-owned by the Indonesian budget airline Lion Air, this has a good range of flights throughout Peninsular Malaysia and also serves Singapore.

malindoair.com. Part-owned by the Indonesian budget airline Lion Air, this has a good range of flights throughout Peninsular Malaysia and also serves Singapore.

MASwings ![]() maswings.com.my. A subsidiary of Malaysia Airlines, MASwings operates on many routes, largely rural, within Borneo, often using nineteen-seater propeller-driven Twin Otter planes that are a lifeline for isolated communities.

maswings.com.my. A subsidiary of Malaysia Airlines, MASwings operates on many routes, largely rural, within Borneo, often using nineteen-seater propeller-driven Twin Otter planes that are a lifeline for isolated communities.

Malaysia Airlines (MAS) ![]() malaysiaairlines.com. Flies between KL and many state capitals, plus Langkawi, Labuan, Singapore and Brunei.

malaysiaairlines.com. Flies between KL and many state capitals, plus Langkawi, Labuan, Singapore and Brunei.

Scoot ![]() flyscoot.com. Singapore’s Airlines’ low-cost wing serves major Peninsular destinations, plus Kuching, from Singapore.

flyscoot.com. Singapore’s Airlines’ low-cost wing serves major Peninsular destinations, plus Kuching, from Singapore.

SilkAir ![]() silkair.com. Singapore Airlines’ non-budget subsidiary operates between Singapore and KL, Penang, Langkawi, Kuching and Kota Kinabalu.

silkair.com. Singapore Airlines’ non-budget subsidiary operates between Singapore and KL, Penang, Langkawi, Kuching and Kota Kinabalu.

By car

The roads in Peninsular Malaysia are good, making driving a viable prospect for tourists – though the cavalier local attitude to road rules takes some getting used to. It’s mostly the same story in East Malaysia and Brunei, though here major towns tend to be linked by ordinary roads rather than wide highways. Singapore is in another league altogether, boasting modern highways and a built-in road-use charging system that talks to a black-box gizmo fitted in every car. All three countries drive on the left, and wearing seat belts is compulsory in the front of the vehicle (and in the back too, in Singapore). To rent a vehicle, you must be 23 or over and will need to show a clean driving licence.

The rest of this section concentrates on Malaysia. For more on driving in Singapore and Brunei, see the respective chapters in the Guide.

Malay vocabulary for drivers

The following list should help decipher road signage in Peninsular Malaysia and parts of Brunei, much of which is in Malay.

Utara North

Selatan South

Barat West

Timur East

Di belakang Behind

Di hadapan Ahead

Awas Caution

Berhenti Stop

Beri laluan Give way

Dilarang meletak kereta No parking

Dilarang memotong No overtaking

Had laju/jam Speed limit/per hour

Ikut kiri/kanan Keep left/right

Jalan sehala One-way street

Kawasan rehat Highway rest stop

Kurangkan laju Reduce speed

Lebuhraya Expressway/highway

Lencongan Detour

Pembinaan di hadapan Road works ahead

Pusat bandar/bandaraya Town/city centre

Simpang ke… Junction/turning for…

Zon had laju Zone where speed limit applies

Malaysian roads

Malaysian highways – called expressways and usually referred to by a number prefixed “E” – are a pleasure to drive; they’re wide and well maintained, and feature convenient rest stops with toilets, shops and small food courts. In contrast, the streets of major cities can be a pain, regularly traffic-snarled, with patchy signposting and confusing one-way systems. Most cities and towns boast plenty of car parks, and even where you can’t find one, there’s usually no problem with parking in a lane or side street.

Speed limits are 110km per hour on expressways, 90km per hour on the narrower trunk and state roads, and 50km per hour in built-up areas. Whatever road you’re on, keep to the speed limit; speed traps are not uncommon and fines hefty. If you are pulled up for a traffic offence, note that it’s not unknown for Malaysian police to ask for a bribe, which will set you back less than the fine. Never offer to bribe a police officer and think carefully before you give in to an invitation to do so.

All expressways are built and run by private concessions and as such attract tolls, generally around RM20 per 100km, though on some roads a flat fee is levied. At toll points (signed “Tol Plaza”), you can pay in cash (cashiers can dispense change) or by waving a stored-value Touch ’n Go card (![]() touchngo.com.my) in front of a sensor. Get in the appropriate lane as you approach the toll points: some lanes are for certain types of vehicle only.

touchngo.com.my) in front of a sensor. Get in the appropriate lane as you approach the toll points: some lanes are for certain types of vehicle only.

Once out on the roads, you’ll rapidly become aware of the behaviour of quite a few Malaysian motorists, which their compatriots might term gila (Malay for “insane”). Swerving from lane to lane in the thick of the traffic, overtaking close to blind corners and careering downhill roads are not uncommon, as are tragic press accounts of pile-ups and road fatalities. Not for nothing does the exhortation “pandu cermat” (drive safely) appear on numerous highway signboards, though the message still isn’t getting through.

If you’re new to driving in Malaysia, the best approach is to take all of this with equanimity and drive conservatively; concede the right of way if you’re not sure of the intentions of others. One confusing local habit is that some drivers flash their headlights to claim the right of way rather than concede it.

Car and bike rental

Car rental rates with the national chains start at around RM150 per day for a basic 1.2-litre Proton, although you may find better deals with local firms. The rate includes unlimited mileage and collision damage waiver insurance; the excess can be RM1500 or more, but can be reduced by paying a surcharge of up to ten percent on the daily rental rate. Both petrol and diesel cost around RM2.30 per litre at the time of writing.

Motorbike rental tends to be informal, usually offered by Malaysian guesthouses and shops in more touristy areas. Officially, you must be over 21 and have an appropriate driving licence, though it’s unlikely you’ll have to show the latter; you’ll probably need to leave your passport as a deposit. Wearing helmets is compulsory. Rental costs around RM20 per day, while bicycles, useful in rural areas, can be rented for a few ringgit a day.

Local car rental agencies

Hawk ![]() 03 5631 6488,

03 5631 6488, ![]() hawkrentacar.com.my.

hawkrentacar.com.my.

Mayflower ![]() 1800 881 688,

1800 881 688, ![]() mayflowercarrental.com.my.

mayflowercarrental.com.my.

Orix ![]() 03 9284 7799,

03 9284 7799, ![]() orixauto.com.my.

orixauto.com.my.

Transport in cities and towns

The companies that run local buses in each state also run city and town buses, serving urban centres and suburbs. Fares seldom exceed RM5, though schedules can be unfathomable to visitors (and even locals). KL also has an MRT and LRT metro system, plus local rail and monorail systems.

Outside the largest cities, taxis do not ply the streets looking for custom, so using one means heading to a taxi rank, typically outside big hotels and malls. Malaysian taxis are notorious for being unmetered except in a few big cities, notably KL, so it’s worth asking locals what a fair price to your destination would be and haggling with the driver before you set off. At a few taxi ranks, notably at airports and train stations, you buy a voucher for your destination at a sensible price. In a few areas it can be worthwhile chartering a taxi for several hours, for example to reach a remote nature park and perhaps collect you when you’re done; prices will depend on the area and your bargaining skills.

The good news for taxi users is that in a handful of big cities, you can now book a ride using the homegrown Grab app (![]() grab.com.my) as well as Uber (

grab.com.my) as well as Uber (![]() uber.com). Grab is particularly useful: fares are distance-based and can work out a third cheaper than using an unmetered taxi, and drivers will pick you up from wherever you are.

uber.com). Grab is particularly useful: fares are distance-based and can work out a third cheaper than using an unmetered taxi, and drivers will pick you up from wherever you are.

Trishaws (bicycle rickshaws), seating two people, are seen less these days, but they’re still part of the tourist scene in places like Melaka, Penang and Singapore. You’re paying for an experience here, not transport as such; details are given in the relevant sections of the Guide.

Accommodation

Accommodation in Malaysia is good value: mid-range en-suite rooms can go for as little as RM120 (£22/US$30). Details of accommodation in Brunei and Singapore are given in the relevant chapters of the Guide.

The cheapest form of accommodation is offered by hostels, guesthouses and lodges, which usually have both dorms and simple private rooms, sharing bathrooms. These places exist only in well-touristed areas, whether urban or rural. Elsewhere, you’ll need to rely on hotels, which range from world-class luxury affairs to austere concrete blocks with basic rooms.

Advance reservations are essential to be sure of securing a budget or mid-range room during major festivals or school breaks. The East Asian accommodation specialist ![]() agoda.com has a wide selection of hotels in all three countries. In addition to “conventional” accommodation, it’s also possible to find apartments in cities using the likes of Airbnb (

agoda.com has a wide selection of hotels in all three countries. In addition to “conventional” accommodation, it’s also possible to find apartments in cities using the likes of Airbnb (![]() airbnb.com).

airbnb.com).

Air conditioning is standard in all but the cheapest hotels, and is fairly common in guesthouses too. Wi-fi is practically standard, although a few (usually pricey) hotels charge extra for it – we have indicated where this is the case in the Guide. Baby cots are usually available only in more expensive places.

Accommodation pricing and taxes

Many mid-range hotels in Malaysia have a published tariff or rack rate and a so-called promotional rate, generally around a third less. What’s important to realize is that the promotional rate is the de facto price, applying all year except, perhaps, during peak periods such as important festivals. To be sure of getting the promotional rate, either book online or call in advance of your arrival.

Top-tier and some mid-range hotels, plus some hostels, have a different strategy: their online booking engines constantly adjust prices according to demand. This means the best rates usually go to those who book early, although some last-minute discounts may also pop up.

Note that mid-range and pricey hotels levy a service charge (usually ten percent) and that most hotels levy GST (six percent). Unless otherwise stated, the accommodation prices quoted in the reviews in this Guide include such surcharges and are based on promotional rates or, at luxury hotels, typical rates.

Finally, there’s the matter of the tourism tax. Introduced in 2017, it essentially requires foreigners to have to pay an additional RM10 per room per night. Naturally, this hits people staying in cheap hotels or in private rooms in hostels especially hard, though dorm occupants may find the tax is divided by the number of beds or even absorbed by the hostel owner. When booking online, if the tax isn’t added you will probably have to pay it upon checking in.

Guesthouses, hostels and lodges

The mainstay of the travellers’ scene in Malaysia are hostels and guesthouses (also called backpackers or lodges – all these terms are somewhat interchangeable). These can range from basic affairs to smartly refurbished shophouses with satellite TVs and games consoles. Almost all offer dorm beds, starting at around RM20, though you can pay double that in fancy establishments. Basic double rooms are usually available for RM50 to RM100 a night, often with mere plywood partitions separating them from adjacent rooms. Breakfast is usually available – a simple self-service affair of coffee or tea and toast.

Chalets

Banish all thoughts of Alpine loveliness when it comes to Malaysian chalets: these are guesthouse and resort rooms in the form of little self-contained wooden or concrete cabins. They’re mostly to be found in rural areas, especially at nature reserves and beaches. Chalets range from cramped, stuffy A-frames – sheds named for their steeply sloping roofs, sometimes with a tiny bathroom at the back – to luxury en-suite affairs with a veranda, sitting area, minibar and the like; prices vary accordingly.

Hotels

Malaysia’s cheapest hotels tend to cater for a local clientele and seldom need to be booked in advance. Showers and toilets may be shared and can be pretty basic, although most places have some en-suite rooms. Another consideration at cheap and even some mid-range hotels is the noise level, as doors and windows offer poor sound insulation. Note that some cheap hotels also function as brothels, especially those that allow rooms to be paid for by the hour.

Mid-range hotels can be better value. Prices start at around RM120 in cities, and less in rural areas and towns, for which you can expect air conditioning, en-suite facilities and relatively decent furnishings, as well, sometimes, a refrigerator, in-room safe and access to a restaurant.

High-end hotels are as comfortable as you might expect, and many have state-of-the-art facilities, including a swimming pool, spa and gym. Some may add a touch of class by incorporating grand extrapolations of kampung-style architecture, such as saddle-shaped roofs with woodcarving. Although rates can be as low as RM250 per night, in big cities they can rocket above the RM400 mark.

In the major cities, look out for boutique hotels, usually set in refurbished shophouses or colonial-era office buildings. They are the most characterful places to stay, offering either retro-style decor or über-hip contemporary features – although never at budget prices.

Hotel breakfasts, where available, are either Asian/Western buffets with trays of noodles next to beans and eggs, or simpler affairs where you order off a menu. They’re usually included in the rate except at four- and five-star places, where the spread is so elaborate that there are two room rates – with and without breakfast. In the Guide listings, we have indicated when breakfast is included in the price.

Camping

There are few official opportunities for camping in Malaysia, perhaps because guesthouses are so reasonably priced, and because the heat and humidity, not to mention the copious insect population, make camping something only strange foreigners would willingly do. Where there are campsites, typically in nature parks, they are either free to use or entail a nominal fee; facilities are basic and may not be well maintained. A few lodges and camps have tents and other equipment for rent, but you generally need to bring your own gear.

If you go trekking in very remote regions, for example in the depths of Taman Negara and the Kelabit Highlands in Sarawak, camping is about your only option. Specialist tour operators or local guides can often provide gear.

Longhouses

A stay in a longhouse, de rigueur for many travellers visiting Sarawak (and also possible in Sabah), offers the chance to experience tribal community life, do a little trekking and try activities such as weaving and using a blowpipe. It used to be that visitors could simply turn up and ask the tuai rumah (headman) for a place to stay, paying only for meals and offering some gifts as an additional token of thanks. While some tourists still try to work things like this, these days most longhouse visits are invariably arranged through a tour operator and can therefore be a little pricey. Gawai is the most exciting time of year to stay.

More expensive packages put visitors up in their own section of the longhouse, equipped with proper beds and modern washing facilities; meals will be prepared separately rather than shared with the rest of the community. More basic trips generally have you sleeping on mats or in hammocks rather than beds, either in a large communal room or on the veranda, and the main washing facilities may well be the nearest river. For meals, the party will be divided up into smaller groups, and each will dine with a different family.

Homestays

In many rural areas especially, homestay programmes offer the chance to stay with a Malaysian family, paying for your bed and board. The arrangement is an appealing one on paper, giving you a chance to sample home cooking and local culture. In practice, however, hosts may not be able to speak much English, a situation that effectively cuts foreign guests off from them and the community. As a result, homestays often end up being used by Malaysian travellers rather than foreigners. Tourist offices can usually furnish a list of local homestays on request, but be sure to raise the above issues if pursuing the idea.

Food and drink

One of the best reasons to come to Malaysia and Singapore (even Brunei, to a lesser extent) is the food, comprising two of the world’s most venerated cuisines, Chinese and Indian, and one of the most underrated – Malay. Even if you think you know two out of the three pretty well, be prepared to be surprised: Chinese food here boasts a lot of the provincial diversity that you don’t find in the West’s Cantonese-dominated Chinese restaurants, while Indian food is predominantly southern Indian, lighter and spicier than the cuisine of the north.

Furthermore, each of the three cuisines has acquired more than a few tricks from the other two – the Chinese here cook curries, for example – giving rise to some distinctive fusion food. Add to this cross-fertilization a host of regional variations and specialities, plus excellent seafood and unusual tropical produce, and the result can be a dazzling gastronomic experience.

None of this need be expensive. From the ubiquitous food stalls and cheap street diners called kedai kopis, the standard of cooking is high and food everywhere is remarkably good value. Basic noodle- or rice-based one-plate meals at a stall or kedai kopis rarely cost more than a few ringgit or Singapore dollars. Even a full meal with drinks in a fancy restaurant seldom runs to more than RM50 a head in Malaysia, though expect to pay Western prices at quite a few places in Singapore. The most renowned culinary centres are Singapore, George Town, KL, Melaka and Kota Bharu, although other towns have their own distinctive dishes too.

Food stalls and food courts

Some of the cheapest and most delicious food available in Malaysia and Singapore comes from stalls, traditionally wooden pushcarts on the roadside, surrounded by a few wobbly tables with stools. Most serve one or a few standard noodle and rice dishes or specialize in certain delicacies, from oyster omelettes to squid curry. One myth to bust immediately is the notion that you will get food poisoning eating at stalls or cheap diners. Standards of hygiene are usually good, and as most food is cooked to order (or, in the case of rice-with-toppings spreads, only on display for a few hours), it’s generally pretty safe.

Many stalls are assembled into user-friendly medan selera (literally “appetite square”) or food courts, also known as hawker centres in Singapore. Usually taking up a floor of an office building or shopping mall, or housed in open-sided market buildings, food courts feature stall lots with menus displayed and fixed tables, plus toilets. You generally don’t have to sit close to the stall you’re patronizing: find a free table, and the vendor will track you down when your food is ready (at some Singapore food centres you quote the table number when ordering). Play it by ear as to whether you pay when ordering, or when the food is delivered.

Stalls open at various times from morning to evening, with most closing well before midnight except in the big cities. During the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan, however, Muslim-run stalls don’t open until mid-afternoon, though this is also when you can take advantage of the pasar Ramadan, afternoon food markets at which stalls sell masses of savouries and sweet treats to take away; tourist offices can tell you where one is taking place. Ramadan is also the time to stuff yourself at the massive fast-breaking buffets laid on by most major hotels.

Eating etiquette

Malays and Indians often eat with the right hand, using the palm as a scoop and the thumb to help push food into the mouth. Chopsticks are, of course, used for Chinese food, though note that a spoon is always used to help with rice, gravies and slippery food such as mushrooms or tofu, and that you don’t pick up rice with chopsticks (unless you’ve a rice bowl, in which case you lift the bowl to your mouth and use the chopsticks as a sort of shovel). Cutlery is universally available; for local food, it’s best to eat mainly with a spoon, using a fork to get food on to it.

Kedai kopis

Few downtown streets lack a kedai kopis, sometimes known as a kopitiam in Hokkien Chinese. Although both terms literally mean “coffee shop”, a kedai kopis is actually an inexpensive diner rather than a café. Most serve noodle and rice dishes all day, often with a campur-style spread at lunchtime, sometimes in the evening too. Some kedai kopis function as miniature food markets, housing a handful of vendors – perhaps one offering curries and griddle breads, another doing a particular Chinese noodle dish, and so on.

Most kedai kopis open at 8am to serve breakfast, and don’t shut until the early evening; a few stay open as late as 10pm. Culinary standards are seldom spectacular but are satisfying all the same, and you’re unlikely to spend more than small change for a filling one-plate meal. In some Malaysian towns, particularly on the east coast, the Chinese-run kedai kopis are often the only places where you’ll be able to get alcohol.

Restaurants, cafés and bakeries

Sophisticated restaurants only exist in the big cities. Don’t expect a stiffly formal ambience, however – while some places can be sedate, the Chinese, especially, prefer restaurants to be noisy, sociable affairs. Where the pricier restaurants come into their own is for international food – anything from Vietnamese to Tex-Mex. The chief letdown is that the service can be amateurish, reflecting how novel this sort of dining experience is for many of the staff.

Most large Malaysian towns feature a few attempts at Western cafés, serving passable fries, sandwiches, burgers, shakes and so forth. It’s also easy to find bakeries, which can offer a welcome change from the local rice-based diet – though don’t be surprised to find chilli sardine buns and other Asian Western hybrids, or cakes with decidedly artificial fillings and colourings. For anything really decent in the café or bakery line, you’ll need to be in a big city.

Cuisines

A convenient, cheap way to get acquainted with local dishes is to sample the spreads available at many kedai kopis, particularly at lunchtime. The concept is pretty much summed up by the Malay term nasi campur (“mixed rice”), though Chinese and Indian kedai kopis, too, offer these arrays of stir-fries, curries and other savouries in trays. As in a cafeteria, you tell the person behind the counter which items you want, and a helping of each will be piled atop a mound of rice. If you don’t like plain rice, ask for it to be doused with gravy (kuah in Malay) from any stew on display.

Nasi campur is not haute cuisine – and that’s precisely its attraction. Whether you have, say, ikan kembong (mackerel) deep-fried and served whole, or chicken pieces braised in soy sauce, or bean sprouts stir-fried with salted fish or shrimp, a campur spread is much closer to home cooking than anything served in formal restaurants.

Nasi campur and noodle dishes are meals in themselves, but otherwise eating is generally a shared experience – stir-fries and other dishes arrive in quick succession and everyone helps themselves to several servings of each, eaten with rice, as the meal progresses.

Breakfast can present a conundrum in small towns, where rice, roti canai and noodles may be all that’s easily available. If you can’t get used to the likes of rice porridge at dawn, you’ll find that many a kedai kopis offers roti bakar, toast served with butter and kaya. The latter is a scrumptious sweet coconut curd jam, either orange or green, not unlike English lemon curd in that egg is a major ingredient.

Malay food

In its influences, Malay cuisine looks to the north and east, most obviously to China in the use of noodles and soy sauce, but also to neighbouring Thailand, with which it shares an affinity for such ingredients as lemongrass, the ginger-like galangal and fermented fish sauce (the Malay version, budu, is made from anchovies). But Malay food also draws on Indian and Middle East cooking in the use of spices, and in dishes such as biriyani rice. The resulting cuisine is both spicy and a little sweet. Naturally there’s an emphasis on local ingredients: santan (coconut milk) lends a sweet, creamy undertone to many stews and curries, while belacan, a pungent fermented prawn paste (something of an acquired taste), is found in chilli condiments and sauces. Herbs, including curry and kaffir lime leaves, also play a prominent role.

The cuisine of the southern part of the Peninsula tends to be more lemak (rich) than further north, where the Thai influence is stronger and tom yam stews, spicy and sour (the latter by dint of lemongrass), are popular. The most famous Malay dish is arguably satay, though it can be hard to find outside big cities. Also quintessentially Malay, rendang is a dryish curry made by slow-cooking meat (usually beef) in coconut milk flavoured with galangal and a variety of herbs and spices.

For many visitors, one of the most striking things about Malay food is the bewildering array of kuih-muih (or just kuih), or sweets, on display at markets and street stalls. Often featuring coconut and sometimes gula melaka (palm-sugar molasses), kuih come in all shapes, sizes and colours (often artificial nowadays) – rainbow-hued layer cakes of rice flour are about the most extreme example.

Chinese food

The range of Chinese cooking available in Malaysia and Singapore represents a mouthwatering sweep through China’s southeastern seaboard, reflecting the historical pattern of emigration from Fujian, Guangzhou and Hainan Island provinces. This diversity is evident in dishes served at hawker centres and kopitiams. Cantonese char siew (roast pork, given a reddish honey-based marinade) is frequently served over plain rice as a meal in itself, or as a garnish in noodle dishes such as wonton mee (wonton being Cantonese pork dumplings); also very common is Hainanese chicken rice, comprising steamed chicken accompanied by savoury rice cooked in chicken stock. Fujian province contributes dishes such as hae mee, yellow noodles in a rich prawn broth; yong tau foo, from the Hakka ethnic group on the border with Guangzhou, and comprising bean curd, fishballs and assorted vegetables, poached and served with broth and sweet dipping sauces; and mee pok, a Teochew (Chaozhou) dish featuring ribbon-like noodles with fishballs and a spicy dressing.

Restaurant dining tends to be dominated by Cantonese food. Menus can be formulaic, but the quality of cooking is usually high. Many Cantonese places also offer great dim sum, at which small servings of numerous savouries such as siu mai dumplings (of pork and prawn), crispy yam puffs and chee cheong fun (rice-flour rolls stuffed with pork and drenched in sweet sauce) are consumed. Traditionally, these would be served in bamboo steamers and ordered from waitress-wheeled trolleys, but these days you might well have to order from a menu.

Where available, take the opportunity to try specialities such as steamboat, a sort of fondue that involves dunking raw vegetables, meat and seafood into boiling broth to cook, or chilli crab, with a spicy tomato sauce. A humdrum but very commonplace stomach-filler is pow, steamed buns containing a savoury filling of char siew or chicken, or sometimes a sweet red bean paste.

Nyonya food

Named after the word used to describe womenfolk of the Peranakan communities, Nyonya food is a product of the melding of Penang, Melaka and Singapore cultures. A blend of Chinese and Malay cuisines, it can seem more Malay than Chinese thanks to its use of spices – except that pork is widely used.

Nyonya popiah (spring rolls) are very common: rather than being fried, the rolls are assembled by coating a steamed wrap with a sweet sauce made of palm sugar, then stuffed mainly with stir-fried bangkwang, a crunchy turnip-like vegetable. Another classic is laksa, noodles in a spicy soup with the distinctive daun kesom – a herb fittingly referred to in English as laksa leaf. Other well-known Nyonya dishes include asam fish, a spicy, sour fish stew featuring tamarind (the asam of the name), and otak-otak, fish mashed with coconut milk and chilli paste then put in a narrow banana-leaf envelope and steamed or barbecued.

Six of the best

The dishes listed below are mostly easy to find, and many of these cut across ethnic boundaries as well, with each group modifying the recipe slightly to suit its cooking style.

Nasi lemak Rice fragrantly cooked in coconut milk and served with fried peanuts, tiny fried anchovies, cucumber, boiled egg and spicy sambal.

Roti canai Basically Indian paratha (indeed it’s called roti prata in Singapore), a delicious griddle bread served with a curry sauce. It’s ubiquitous, served up by Malay and Indian kedai kopis and stalls.

Nasi goreng Literally, fried rice, though not as in Chinese restaurants; Malay and Indian versions feature a little spice and chilli, along with the usual mix of vegetables plus shrimp, chicken and/or egg bits.

Char kuay teow A Hokkien Chinese dish of fried tagliatelle-style rice noodles, often darkly coated in soy sauce and garnished with egg, pork and prawns. The Singapore version is decidedly sweet. Malay kuay teow goreng is also available and tends to be spicier.

Satay A Malay dish of chicken, mutton or beef kebabs on bamboo sticks, marinated and barbecued. The meat is accompanied by cucumber, raw onion and ketupat, cubes of sticky rice steamed in a wrap of woven leaves. All are meant to be dipped in a spicy peanut sauce. Chinese pork satay also exists.

Laksa A spicy seafood noodle soup, Nyonya in origin. Singapore laksa, served with fishcake dumplings and beansprouts, is rich and a little sweet thanks to copious use of coconut milk, while Penang’s asam laksa features flaked fish and a tamarind tang.

Indian food

The classic southern Indian dish is the dosai or thosai, a thin rice-flour pancake. It’s usually served accompanied by sambar, a thin vegetable and lentil curry; rasam, a tamarind broth; and perhaps small helpings of other curries. Also very common are roti griddle breads, plus the more substantial murtabak, thicker than a roti and stuffed with egg, onion and minced meat, with sweet banana versions sometimes available. At lunchtime many South Indian cafés turn to serving daun pisang (literally, banana leaf) meals comprising rice heaped on a banana-leaf “platter” and small, replenishable heaps of various curries placed alongside. In some restaurants you’ll find more substantial dishes such as the popular fish-head curry (don’t be put off by the idea – the “cheeks” between the mouth and gills are packed with tasty flesh).

A notable aspect of the eating scene in Malaysia is the “mamak” kedai kopis, run by Muslims of South Indian descent (and easily distinguished from Hindu Tamil places by the framed Arabic inscriptions on the walls). Mamak establishments have become de facto meeting places for all creeds, being halal and open late, often round the clock. Foodwise, they’re similar to other South Indian places, though with more emphasis on meat.

The food served in North Indian restaurants (found only in big cities), is richer, less fiery and more reliant on mutton and chicken. You’ll commonly come across tandoori dishes – named after the clay oven in which the food is cooked – and in particular tandoori chicken, marinated in yoghurt and spices and then baked. Breads such as nan also tend to feature rather than rice.

Special diets

Malay food is, unfortunately, a tough nut to crack for vegetarians, as meat and seafood are well blended into the cuisine. Among the standard savoury dishes, vegetarians can only really handle sayur lodeh (a rich mixed-veg curry made with coconut milk), tauhu goreng (deep-fried tofu with a peanut dressing similar to satay sauce) and acar (pickles). Chinese and Indian eating places are the best bets, thanks to the dietary influence of Buddhism and Hinduism. Chinese restaurants can always whip up veg stir-fries to order, and many places now feature Chinese vegetarian cuisine (usually also good for vegans), using textured veg protein and gluten mock meats – often uncannily like the real thing, and delicious when done right.

Strict vegetarians will want to avoid seafood derivatives commonly used in cooking. This means eschewing dishes like rojak (containing fermented prawn paste) and the chilli dip called sambal belacan (containing belacan, the Malay answer to prawn paste). Oyster sauce, often used in Chinese stir-fries, can easily be substituted with soy sauce or just salt. Note also that the gravy served with roti canai often comes from a meat curry, though some places offer a lentil version, too.

If you need to explain in Malay that you’re vegetarian, try saying “saya hanya makan sayuran” (“I only eat vegetables”). Even if the person taking your order speaks English, it can be useful to list the things you don’t eat; in Malay you’d say, for example, “saya tak mahu ayam dan ikan dan udang” for “I don’t want chicken or fish or prawn”. Expect a few misunderstandings; the cook may leave out one thing on your proscribed list, only to put in another.

Halal food

Halal food doesn’t just feature at Malay and mamak eating places. The catering at mid-range and top-tier Malaysian hotels is almost always halal (or at least “pork-free”), to the extent that you get turkey or beef “bacon” at breakfast. Of course, the pork-free billing doesn’t equate to being halal, but many local Muslims are prepared to overlook this grey area.

In areas where the population is largely Muslim, such as Kelantan and Terengganu, halal or pork-free food is the norm, even at Chinese and Indian restaurants. In largely Chinese Singapore, most hawker centres have a row or two of Muslim stalls.

Borneo cuisine

The diet of the indigenous groups living in settled communities in East Malaysia can be not dissimilar to Malay and Chinese cooking. In remoter regions, however, or at festival times, you may have an opportunity to sample indigenous cuisine. Villagers in Sabah’s Klias Peninsula and in Brunei still produce ambuyat, a gluey, sago-starch porridge; then there’s the Lun Bawang speciality of jaruk – raw wild boar, fermented in a bamboo tube and definitely an acquired taste. Sabah’s most famous dishes include hinava, raw fish pickled in lime juice. In Sarawak, Iban and Kelabit communities sometimes serve wild boar cooked on a spit or stewed, and served with rice (perhaps lemang – glutinous rice cooked in bamboo) and jungle ferns. River fish is a longhouse basic; the most easily available, tilapia, is usually grilled with pepper and herbs, or steamed in bamboo cylinders.

Desserts