The Arizona desert can be a daunting place when the wind blows. Joe Elliott and I had driven south from Montana in January for a week of Gambel’s quail hunting, and had set up camp on public land about thirty miles north of the small town of Wickenburg. As we sat around the campfire that night under a clear, calm sky, a windstorm was the last thing on our minds.

About 2 a.m. the sound of tent canvas flapping wildly in the wind awakened us. A cooking pot whizzed off into the desert, and a moment later our camp stove and stove stand went down with a crash. We bolted from our cots and grabbed boots and flashlights. The tent, an old Coleman cabin-style model that had seen heroic duty over the years, was listing and close to collapse.

We quickly rounded up extra ropes and staked out guy lines from the tent’s corner poles. Then we stumbled around the desert gathering up plates, pans and other items we had left sitting out. A few things disappeared forever; they probably came to earth in the next county.

By morning the wind had subsided. The whole episode seemed like a bad dream. “I wonder how hard it blew last night,” Joe said, his cold fingers wrapped around a steaming mug of coffee. His eyes were red and his voice scratchy, like he’d swallowed a tablespoon of sand.

“If we were closer to the ocean I’d say it was a hurricane,” I replied, spitting out grit. “There’s sand in everything, including my teeth.”

There was nothing left to do but gather our strength and go looking for quail. We unloaded our Brittanys, Groucho and Rana, and headed for a sandy wash where we had noticed quail tracks the night before. We hadn’t gone far down the mesquite-lined draw when Groucho’s bell stopped, started, then stopped again. I caught a glimpse of a Gambel’s quail darting ahead, its jaunty black topknot bobbing through the green prickly pear.

“There’s a covey ahead!” I yelled. A quail flushed, then a bunch of quail took off in a rush of wings. I couldn’t see exactly where they put down, but I had a rough idea. After a fifteen-minute search we bumped a single, then a pair of birds. Joe scratched down the single with his second barrel, and I tumbled a cockbird from the pair. We spent the next hour chasing this covey, then stumbled into another one on the way back to camp. By the time we arrived there, we had eight quail between us.

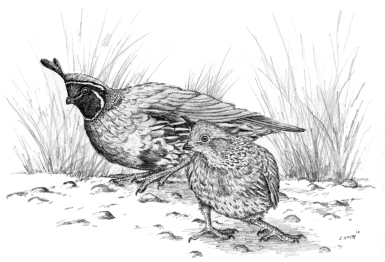

Although Gambel’s quail look gray from a distance, in hand they are striking birds, especially the males with their black face rimmed in white, chestnut crown, and cream-colored belly splotched with black. Females lack the distinctive head markings but like the males they have a dark topknot and rusty flanks streaked with white.

In camp we ate lunch, watered the dogs, cleaned birds, and enjoyed the shirtsleeve warmth. When the temperature began to drop later in the afternoon we drove to another streambed that had an intermittent flow of water. Mesquite and paloverde trees bordered the sandy wash, while saguaro cactus, ocotillo, prickly pear, and yucca dotted the adjacent hillsides. We found the first covey not far from the truck; they flushed out of range and we followed them a few hundred yards up the wash where we rousted them again. This time they scattered into the desert.

Working back and forth through the area several times produced a number of points and close flushes. Gambel’s quail are strong runners, but once a covey breaks up the singles hold well. They don’t give off much scent in the dry climate and it’s easy for dogs to miss them. The best strategy is to cover the area thoroughly, starting and stopping frequently. Sometimes if you hang around long enough the birds will begin to move and put out more scent for the dogs.

I shoot a 12 gauge over/under choked improved cylinder and modified, but a 20 gauge will do the job. Shot size is more important than gauge. I like standard trap loads with No. 7½ shot (1⅛ oz.). Some hunters drop down to No. 6 if birds are flushing wild. No. 8 shot is too light. Gambel’s quail are tough birds and if they aren’t well hit they’ll take off running and disappear into the desert, usually into a packrat midden. My dogs have dug them out of such places several times, a process that makes me nervous because snakes also use these burrows. I’ve yet to run into a rattlesnake, but all my Arizona hunts have been in December and January when nighttime temperatures drop close to freezing.

Our afternoon hunt yielded three more quail apiece. Groucho had a couple of encounters with cactus that required my help. The area we were hunting had a scattering of jumping cholla, a cactus that sheds small, spiny segments onto the ground where unsuspecting dogs can step on them. When Groucho stopped and began biting at his paw, I guessed correctly he had a piece of cholla in his foot. I either wear leather gloves or carry them in my hunting vest, along with a comb and needle-nose pliers. Dislodging pieces of cactus from a dog’s foot or face with a comb will save your fingers from getting stabbed. Leather gloves help but spines can go through them. Pliers come in handy when spines become embedded in a paw or leg. Dogs have mishaps with prickly pear, too, but cholla is the main villain. It’s best to avoid areas heavily infested with it.

Due to the rugged nature of the Sonoran desert, most dogs visiting for the first time end up with sore feet. I keep a close eye on my dogs and use Lewis dog boots at the first sign of distress. But dogs aren’t the only ones to have cactus problems. Almost everything growing in the desert has thorns or spines and hunters get punctured from time to time. Large thorns can be pulled out easily but small spines may require a tweezers. I carry a good pair that will grasp and hold a small spine or sliver. Once while hunting I tripped and brushed against a waist-high prickly pear cactus. I had at least a hundred spines in my arm, most of them tiny hairlike ones that I could hardly see. It took me more than an hour to get them out. I thought I’d be sore for days, but by the next morning my arm felt fine.

The sun sets quickly in the desert. One minute it’s warm and sunny, the next minute it’s dark and getting cold. One night at sundown we began a firewood search, grabbing whatever dead branches, sticks, and chunks of wood we could find. We got a blaze going in the fire ring and sat down to enjoy dinner and a cold brew. Exhausted from travel and hunting, we sat half asleep in our folding chairs when the campfire hissed and exploded, sending a shower of sparks skyward. I jumped up to brush the sparks off my coat, and Joe did an Irish jig of his own. Groucho, who had been snoozing next to the fire, hid under the truck.

We sat down again but it wasn’t long before another explosion sent us scrambling. Fortunately there was no wind to carry off the embers so we didn’t set the desert on fire. Many desert trees and shrubs have a high oil content but not all of them explode. Mesquite burns slow and hot, forming a beautiful bed of coals. Our mystery wood kept us hopping until we finally gave up and doused the fire.

The next morning we explored an arroyo a few miles from camp and put up a small covey of quail after a half-hour walk. We scattered the birds and bagged a few singles as dark clouds rolled in from the west. We missed more than we hit, which we blamed on the darkening sky. Gambel’s quail make challenging targets even in bright sunshine, but on cloudy days the birds’ grayish backs and tails make them especially hard to see against the muted desert landscape. Some hunters swear by shooting glasses with yellow lenses that add sharpness and contrast.

There were a few sprinkles on the truck windshield by the time we got back to camp. The radio confirmed we were in for a change in weather—a front was moving in from California and the twenty- four-hour forecast promised colder temperatures and rain. After lunch the rain began to beat a steady tattoo on the tent roof. Joe tempted fate when he asked, “It’s the desert, right? How much can it rain in the desert?”

By the next day the Sonoran desert had answered: It can rain a lot. By the time the storm subsided we had named the tent “Old Leaky.” To help pass the time I thumbed through my Audubon guide to North American deserts. “It says here the Sonoran is considered moist by desert standards.”

Joe shot me a disgusted look. “No kidding.”

“It also says prolonged winter rains can drive hibernating snakes out of the ground and up into trees. We could have rattlesnakes, of which there are eleven species in Arizona, hanging from the branches like Christmas ornaments.”

The rain stopped during the night and the next day dawned clear and cold. We spent the morning drying our gear and waiting for the roads to drain a bit before setting out again. That afternoon we tried a new spot a few miles from camp where the desert climbed toward rugged brown foothills. Rana and Groucho ranged in front of us, threading their way among prickly pear and thorn bushes.

As we worked along a ridge we heard quail calling ahead. A short time later both dogs’ bells fell silent. Gambel’s quail don’t wait around for dogs and hunters, so Joe and I jogged ahead. I spotted Groucho on point just as a covey roared off behind a mesquite tree. Even a small covey makes a racket when it flushes, but judging by the noise this one had to be a “winter covey” containing dozens of birds.

Gambel’s quail numbers fluctuate from year to year, mostly in response to winter precipitation. Briefly put, winter rains produce abundant green plants, setting the stage for a good hatch the following spring. Quail grow fat on the vitamin-rich plants and go into breeding season in peak condition. Green plants also promote higher insect populations, which are vital to survival of newly hatched quail. Gambel’s chicks depend on beetles, worms, caterpillars, and grasshoppers the first few days of their lives. In dry years, when plant life and insects are scarce, desert quail may fail to mate.

Joe and I were now reaping the benefits of several wet winters in succession. As we sweated our way up the steep, rock-strewn hillside in the direction the covey had flown, Groucho and Rana rewarded us with several points. This area had better grass cover than we had found down lower, providing lots of hiding spots for quail. I connected on two singles in a row, then missed a couple. Joe made a good shot on a bird that barreled downhill like a miniature chukar. Several quail flushed and darted behind trees or bushes and escaped. As we circled the area we flushed and bagged several more birds.

Groucho is gone now, but I think he liked hunting Gambel’s quail more than he did any other bird despite the inhospitable terrain. For him, I’m sure it was the intoxicating scent. I like hunting them too, but it goes deeper. I fell in love with the Sonoran desert with its candelabra-shaped saguaros and abundant wildlife on my first visit. I’ve returned many times, in good quail years and bad, and enjoyed every trip. Trekking through the desert on a Sonoran safari, when states farther north are locked in the deep freeze, is a great way to finish the hunting season.