First a downwind zinger raced by and I shot behind it. Then an upwind floater tooled past, and I had the impression it wasn’t moving at all. I shot behind that one, too. My gracious host, Kansan Bill Nye, grinned. “You have to get that gun barrel moving a tad faster if you want mourning dove for dinner,” he said. I mopped my perspiring brow, slapped a mosquito, and made a mental note to get the gun in front and keep swinging.

Since that first dove hunt many years ago I’ve hunted doves in several states, including Montana, where doves became legal game in 1983. A number of northern states have joined Montana in holding dove seasons, including North Dakota, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Doves migrate south in early fall, but a September 1 opener gives northern hunters a chance to test their skills on a bird regarded as a true test of wingshooting prowess.

Hunting pressure nationwide is intense, with close to twenty million birds harvested annually. That may seem like a lot, but the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service estimates there are 350 million doves at the start of hunting season each fall. Annual mortality ranges from 60 to 80 percent, even in states that don’t have hunting seasons. Doves can sustain these high losses because they breed throughout the continental U.S. as well as southern Canada and Mexico, and they raise several broods during the summer.

Each fall hundreds of thousands of hunters across the country take to the field in pursuit of mourning doves. Most of them cuss and sputter their way through more than a box of shells to get a limit (ten to fifteen birds), and feel proud of themselves at that. When dove season opens, ammunition makers rub their hands in glee.

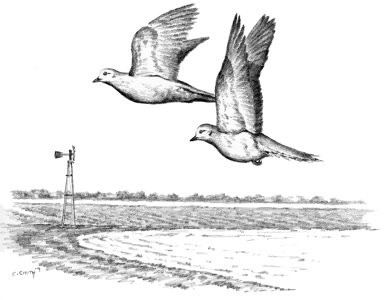

What makes doves so tricky? For one thing, they breeze right along—they’ve been clocked at fifty-five miles per hour. But even more daunting is their erratic flight pattern, which the late John Madson referred to as the dove’s “odd flickering quality.” In his book The Mourning Dove, Madson asserts, “When a cruising dove is fired upon, it may perform amazing acrobatics in the twinkling of an eye. No other game bird has such a dazzling change of pace. I’ve seen doves do a complete roll in the process of turning and diving… . Unless one has hunted doves, he can have no idea of how agile they really are—or how fast.”

I found this out for myself one windy September afternoon near Valentine, Nebraska. Two friends and I had taken stands at strategic locations around an abandoned homestead. I chose an opening in a wooded area not far from a dilapidated barn, Jon a hemp patch at the site of an old corral, and Clark a pasture at the opposite end of the hemp. It wasn’t long before we had action. Most of my birds came in fast over the cottonwood trees from behind me or came in high straight toward me. I soon had a pile of empty shells at my feet, but I also had nine doves—one short of the Nebraska limit. I wanted that tenth dove badly.

Jon and Clark had their limits and came over to lend moral support. A dove whistled by at the speed of sound. I missed. Clark grinned. A gray-brown missile twisted in over the treetops to my left. I missed again. Jon snickered. A brown bombshell came straight at me from out of nowhere. I missed the safety. My Brittany, Chief, whined. The matter finally came to a head.

Jon said, “Dave, we’re hungry so we’re leaving now. You can stay here all night if you want. It’s only a five-mile walk to camp.” Just then, another dove flitted into view. I threw my 20 gauge to my shoulder and fired, and the dove collapsed in a bundle of feathers. Everyone cheered but Chief—he was busy retrieving the dove.

Successful dove hunting requires preseason scouting, which involves driving the back roads in early morning and late afternoon when the birds are out seeking weed or sunflower seeds and waste grain. The presence of several doves perched on utility wires, fences, or dead trees during feeding periods is a good indication there are more on the ground nearby.

After feeding, doves fly to water. Because they like to land and walk around in the open where they can see in all directions, they don’t like ponds with steep or brushy banks. They prefer to land, then walk to the water’s edge to dip their beaks. Ponds with flat, open shorelines with mud or gravel are best. Just before or after sunset, they fly to roost trees.

Doves follow the same flight patterns between feeding, drinking, and roosting areas, so it pays to set up somewhere in the flight path. This might be a ditch bank, fencerow, or shelterbelt near a picked grain field, or a grove of trees or patch of brush near a stock pond. Doves don’t have the wariness of ducks and geese, but wearing camouflage clothing and keeping still until birds are in range is a must.

Because downed birds can be hard to find when they fall in dense cover, it helps to have a dog for the retrieving chores. Most dogs like retrieving doves, and it’s a good early season tune-up for them. It’s usually warm in Montana when dove season opens on September 1, so I carry plenty of water and watch for any signs of heat stress.

While I’ve done most of my dove hunting in early fall, I’ve had some memorable late-season hunts in Arizona. One December evening two friends and I, and my Brittany, Chief, staked out a small stock pond near the Mexican border. As we sat shivering, hidden in a grove of mesquite trees, the sun began to sink toward the horizon with not a dove in sight.

Just as we began to think we’d picked a bad spot, wings whistled, and half the doves in Santa Cruz County descended on our little waterhole. We emptied our guns, reloaded, and emptied them again. Then it grew quiet. The sun dropped below the horizon, signaling the end of legal shooting time.

With Chief’s help, we retrieved the doves, counted, argued, and counted again. One dove short. Or were we? No longer sure, we picked up our empty shell casings and headed for the truck. Somewhere along the way, we lost track of Chief; back at the truck I grew worried and began calling for him. When he appeared, a white speck growing larger in the gathering dusk, he had the missing dove in his mouth.

I hunt doves with a 12 or 20 gauge over/under and use No. 7½ or 8 shot. On incoming doves I fire the tighter barrel first, leaving the more open choke for the next shot, which is likely to be closer. On outgoing birds I do the opposite. I find that I score best when I wait until the birds are in range, then mount the gun, swing through and pull the trigger in one fluid motion. Tracking birds too long causes your arms to tense up, slowing your swing just when it should be speeding up.

Doves can be humbling, so I take along plenty of shells. The national average is two doves downed for every five shots fired. I’ve done better than that but I’ve also done worse, especially on windy days. Even long-time dove shooters have hot and cold streaks that leave them beaming with satisfaction or gnashing their teeth in frustration.

Doves weigh only about five ounces, but that doesn’t detract from their culinary appeal. It just takes a few more of them to make a meal. Doves can be skinned or plucked, and the meat is dark, rich, and delicious. When I’m on a dove stand I lay my birds in the shade where air can circulate around them, rather than putting them in my game bag. The faster they cool, the better they keep. When I’m back at the truck, I store them in a cooler unless I’m planning to clean them right away.

Late on a September afternoon last fall Joe Elliott and I found a spot where doves were flying from a grain field to an area with trees nearby for roosting. It wasn’t the dove bonanza we’d hoped for, but enough to provide some shooting and with luck a grilled dove dinner. I took a stand next to an old cottonwood and waited while Joe walked through a nearby shelterbelt to see if he could stir up a few birds.

When I heard Joe shoot I looked in his direction to see if a dove might be headed my way. A few seconds later a gray missile cruised into view. As I mounted my gun, the dove saw me and dipped two feet just as I slapped the trigger. The shot string whistling over its head sent the dove into high gear and I shot three feet behind. No doubt about it, the gray darter is an ammunition maker’s best friend.