We rarely ran into bobwhite quail when I was a kid growing up in west-central Wisconsin. We must have been at the northern edge of the bobwhite’s range, because when we hunted counties south of Eau Claire we would see an occasional covey, while hunting to the north we never did. Shooting a quail was cause for celebration and I only remember bagging a few. According to Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine, bobwhites have declined steadily in southern Wisconsin since the 1940s due to shrinking habitat.

When I worked for a time in the Twin Cities my friend Rod Sando and I made several trips to Iowa to hunt pheasants and quail. There were good numbers of both species south of Des Moines in those days. If we could find an empty farmstead with an Osage orange hedgerow, we often found a covey of bobwhites.

Rod had a reputation as an expert ruffed grouse hunter and had gotten to know some of the Minnesota Vikings who liked to hunt. One of them was the late Wally Hilgenberg, a linebacker who had the distinction of playing in all four of the Vikings’ Super Bowl appearances.

Wally was from southern Iowa and had relatives in Coon Rapids, a small town in the western part of the state. Rod had hunted with Wally and his uncle and cousins in the Coon Rapids area a number of times, and he invited me to go along on his next trip. Wally couldn’t get away, so it was just Rod and me.

I remember sitting in the cafe in town having breakfast and noticing the locals glancing our way and whispering. At first I figured we had parked illegally or skipped out on our bar tab the night before, but judging by how nice everyone had been treating us it didn’t seem like we were headed for the hoosegow. The waitress couldn’t stay away from our table with her coffee pot, and she seemed especially impressed with Rod.

When I mentioned it, Rod laughed. “We’re celebrities, Dave. Because I’ve hunted down here with Wally Hilgenberg they figure we’re pro athletes.”

“Yes, but we’re not big enough to be pro football players. So who do they think we are?”

“When Wally first introduced me around here as Rod Sando, some of the folks got me confused with Ron Santo.” Ron Santo was an all-star third baseman with the Chicago Cubs, and he and Rod were about the same age. I started to sweat, wondering whose name I should sign in case someone asked for my autograph. We left a big tip and talked a little baseball at the cash register. It may have been a coincidence, but getting permission to hunt wasn’t a problem on that trip. Word travels fast in small towns.

The bobwhite quail is our most widely distributed upland game bird, with the exception of the mourning dove. Its range extends throughout the South, much of the Midwest, and in the East as far north as Massachusetts. Bobwhites stretch west through Texas and into eastern New Mexico. Sadly, they have declined throughout much of their range. Urban sprawl, shrinking grasslands, and changes in farming practices have all taken their toll.

Having never lived in the heart of bobwhite country, I can’t speak with authority about hunting them. But I’ve gone on many an armchair quail hunt with a good book instead of a shotgun. To get the flavor of hunting Gentleman Bob in the Old South, you can’t go wrong by reading Havilah Babcock, Nash Buckingham, and Archibald Rutledge. For a comprehensive look at quail history, biology, and hunting, Charles Elliott’s book, Prince of Game Birds: The Bobwhite Quail, is a good read. Joel Vance’s Bobs, Brush, and Brittanies will teach you plenty about birds and bird dogs and keep you smiling the whole time.

The late Charley Waterman, who for years divided his time between Livingston, Montana, and Deland, Florida, wrote about chasing quail among the pines and palmettos of his winter home. Charley, who grew up in Kansas bobwhite country and hunted them throughout their range, was an expert on the subject. One November when I left my home in Helena to embark on a Nebraska quail hunt, I stopped in Livingston to ask Charley for advice. I’d never met him in person, although I’d talked to him on the phone a couple of times.

When I arrived at his house he was kind enough to invite me in, talk about quail and Hungarian partridge hunting for an hour, and autograph my copy of his book, Hunting Upland Birds, the first chapter of which is devoted to the bobwhite. When he walked me out to my car—a 1975 Ford Pinto loaded to the roof with hunting gear, my Brittany riding shotgun—he did a doubletake. “Say,” he said, “isn’t that one of those exploding Pintos?” The Ford Pinto had a design flaw that made the gas tank prone to being ruptured in a rear-end collision, ending in the fiery death of its occupants.

“Yes,” I said, “but I’ve driven it several years without a problem.” Charley had a concerned look on his face as I drove away, not unlike a worried father sending his son off to war.

I made the long trip to Lincoln, Nebraska, without being incinerated and met my friend Jon Farrar at his house. After we’d had a cup of coffee and discussed our hunting plans, he eyeballed my unconventional hunting rig. “Hey,” he said, “isn’t that one of those exploding Pintos?”

Jon and I hunted quail and pheasants around Lincoln for the next few days with good success. I was anxious to hunt bobwhites with my Brittany, Chief, because I had the idea I might get around to hunting all the upland game birds in the continental U.S. with him, as Charley Waterman had done with a legendary Brittany named Kelly. As it turned out, Chief and I didn’t get them all, but we came close.

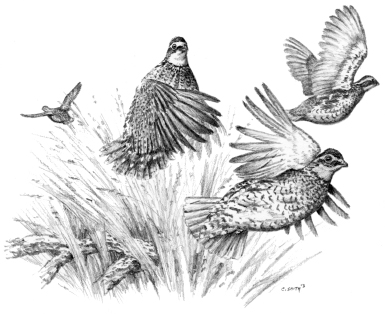

I figured, correctly, that Chief would quickly learn to handle the tight-sitting bobwhites, since he’d had plenty of experience with Huns back in Montana. When he skidded to a point in a weedy draw the first morning, I forgot everything Charley Waterman had told me. “They’re likely to get up right in your face,” Charley said, “and they’ll give you the impression they’re going faster than they really are. Don’t hurry too much and remember to pick out one bird at a time.”

Of course, the explosive covey rise rattled me and I shot too fast. For such small birds, they make a lot of noise. Havilah Babcock, a University of South Carolina English professor and poet laureate of southern quail hunting, explained it this way: “Seven ounces of avoirdupois could be wrapped up in no other shape or form that would possess such power to befog and confound the senses or to disconcert and disorganize the human nervous system.” I missed with the first barrel but scratched one down with the second. An hour later Chief pointed again near the edge of a cornfield. This time I calmed my nerves and doubled on the covey rise, a performance I repeated only once during the remainder of the trip.

My most vivid recollection came on the last afternoon of our hunt. Late in the day Jon and I scattered a covey at the edge of a woodlot, and I shot two singles over Chief’s points. The third bird he pointed flew into the woods, dodging through the oak trees. I thought I saw it slant down at my shot, but I lost sight of it in the thick undergrowth. The sky was growing darker, and I didn’t think I had much chance of finding it, but I urged Chief to “hunt dead.” He disappeared while I scuffled around in the leaves and twigs carpeting the ground, hoping for a miracle. A cold wind muttered through the trees, sending the brown oak leaves still clinging to the branches into a nervous chatter. When I heard his bell getting louder, I turned to see him coming toward me with the pretty little cock quail in his mouth, just as amber rays from a dying sun washed across the woodlot.

While my experience with bobwhites may be limited, I’ve shot a lot of Mearns quail in southern Arizona with No. 8 trap loads. Like bobwhites, these birds hold tight for a pointing dog. Most shots are in heavy cover at close range, requiring a gun choked skeet or improved cylinder—a combination that also works well for bobwhites.

There are no bobwhite quail in Arizona, unless you count the masked bobwhite, a subspecies on the endangered species list. While visiting southern Arizona a few winters ago, I drove up a gravel road south of Tucson into the Santa Rita Mountains. Past the turnoff to Madera Canyon, a popular birding spot that hosts a rare, long-tailed bird called the elegant trogon, the Box Canyon Road winds upward through a narrow canyon. On top the terrain levels out into rolling, oak-covered hills, part of the Coronado National Forest. I pulled off at a roadside turnout to let my Brittany, Ollie, water the trees.

There was a public access sign at the barbed-wire fence, so I went through the gate and started up a well-worn trail to look around. Out of nowhere appeared two Brittanys with a pair of hunters not far behind. I hadn’t seen a soul for the past hour—or another vehicle—so I was surprised, to say the least. The hunters, both carrying vintage 28-gauge double guns that made my mouth water, said they hadn’t seen any Mearns quail that morning, but they had found them here on previous trips.

Like a dutiful greenhorn, I asked them about the trail. “It’s the Arizona Trail,” said one. “It goes north from the Mexican border all the way to the Utah.” Then I asked them if they’d ever run across a masked bobwhite. They laughed and said the masked bobwhite lives only on the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge, forty miles south, right on the Mexican border. “And down there,” said one, “you’re more likely to find a drug smuggler or a Mojave rattlesnake than a masked bobwhite.”