While packing for a duck hunting trip last fall, moving gear from the house to the truck, I carelessly left the kitchen door ajar. Preoccupied with my chores, I didn’t notice that my two-year-old black Lab, Bailey, had slipped out of the house. When I realized she was missing, I got the sinking feeling all dog owners dread.

I hurried up and down the gravel road in front of the house calling her name. No luck. Then, as I was getting in the truck to search the neighborhood, I saw her coming down the road. She had something in her mouth, which turned out to be an apple from my neighbor’s yard. Maybe it was her way of telling me she’d be a good retriever if I took her along on the trip. She needn’t have worried, since she is as important to my waterfowl outings as my shotgun and waders. Relieved, I took the apple and gave her a hug.

This small incident reminded me of how much we hunters care about our dogs. When they are sick, hurt, or lost, we suffer, much as we would for any member of our family. But then, retrievers are family. They play with our kids, guard our houses (sort of), give us their unconditional love. Sure, sometimes they make us want to tear our hair out, but most of the time they make us laugh. They’d be our pals even if they didn’t retrieve ducks and geese.

We shepherd them through their too-short lives, just as they guide us from one milestone to the next in our own lives. Think about it. The bundle of puppy energy you bring home when you send your daughter off to first grade may be around to retrieve her first duck, check out her first date, and see her off to college.

Just as we humans pass through childhood, adolescence, early adulthood, and finally maturity, retrievers progress through four life stages: exuberant puppy, promising young dog, master hunter, and golden ager. Along the way, our relationships with our dogs change. We start out as protector and provider, progress to trainer, then to hunting partner, and finally to companion. Of course, we are to some degree all these things throughout a dog’s life, but over time our responsibilities shift and our bond grows.

I’ve been lucky enough to accompany several fine retrievers along their life’s journey. Each has been special, and each has taught me something new. Like most retrievers, my Lab pup Bailey liked carrying things right from the start: a rolled-up pair of socks, a favorite toy, a pint-size training dummy. During our walks in the hills above my house, she brought me a steady stream of pinecones and old deer bones. I made a fuss over each prize, because it’s always good to reinforce a puppy’s retrieving instinct.

That instinct is a wonderful thing … most of the time. There came a summer evening when Bailey ran up the road near my house at dusk and began to bark. As I strained to see through the fading light, she started toward me with something black and white in her mouth. Even before the scent hit, I knew what it was: a half-grown skunk from a family I had seen a few days earlier. I panicked and yelled, “Drop it!” She hesitated, then loosened her grip. The skunk scurried into the grass and disappeared, unlike its essence, which clung to Bailey’s coat for several weeks.

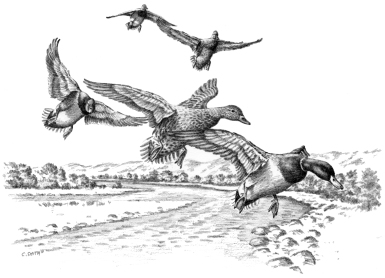

Like your child’s first words, a pup’s first duck hunt is something you never forget. Bailey’s debut came on a foggy morning at a marsh in northern Montana. A friend and I put out our decoys before daylight, and then sat down to wait for the first seams of light to crack the horizon. When coots pattered noisily along the shoreline, Bailey shivered with excitement. Shortly after legal shooting time, a flock of pintails swept over the decoys. My hunting partner and I each dropped a bird. Bailey proudly brought one back while Joe’s dog, Sedge, retrieved the other. That first retrieve, where Bailey’s genes and training first collided with opportunity, remains a cherished memory.

I got a late start as a waterfowler. I grew up hunting ruffed grouse and rabbits with my dad, but we didn’t hunt ducks. It wasn’t until I got out of college and joined some hunting buddies on a trip to Saskatchewan that the waterfowling bug bit. Once it grabbed me, it didn’t let go. One of my friends had a yellow Lab, and after a week of watching this impressive dog work, I knew I’d have a retriever of my own one day.

A year later, I stood at the edge of a pond talking with a man about a young black Lab named Bullet. She was a field-trial washout, he said. He didn’t want to sell her, but he had too many dogs. I told him I could only afford fifty dollars—I was in graduate school, just getting by. He started to walk away, but turned around and looked me in the eyes.

“Will you hunt her?” he asked.

“Every chance I get.”

“Okay, she’s yours.”

Just like that, I had a retriever. Why he sold her to me remains a mystery, because no retriever ever hit the water harder. She had heart and courage—qualities you can’t instill in a dog but can only hope are there from the start. Like many enthusiastic Labs, Bullet could be headstrong. Maybe the man had trouble with her independent streak. To her dying day, she thought she knew more about finding downed birds than I did, and most of the time she was right.

True to my promise, I took Bullet hunting every weekend, and some days when I should have been in school. My classwork suffered, but my waterfowling knowledge grew, along with Bullet’s retrieving skill. In time I taught her to take a line, stop on a whistle, and take hand signals. In return, she taught me patience, and to trust the infallibility of her nose.

As writer Vance Bourjaily observed, “Hunters make errors; dogs correct them.” While hunting a pond one day I sailed a mallard into shoreline cattails a long way from the blind. Bullet’s view of the bird had been blocked, but I had marked the spot well. When we got to the area, she charged into the cattails and disappeared. I figured she’d quickly return with the bird. Instead, she emerged from the cattails and, nose to the ground, ran into a grassy field adjacent to the pond. Thinking she’d forsaken the wounded duck for a hot pheasant trail, I tooted on my whistle. When she came out of the field five minutes later, she had a lively mallard in her mouth.

The next year two friends and I traveled one cold November weekend to a river in central Montana. Arriving in the afternoon, we split up to look for a spot where we might set out our decoys in the morning. Exploring downstream, my dogless hunting partners jumped a flock of mallards and winged two greenheads that sailed across the river to the far shore. Above the wind, I heard a plaintive call: “Bringgg the doggg!”

As they pointed out where the birds had fallen, sleet whipped across the water, stinging our eyes. I guessed how far the current would carry Bullet downstream as she crossed the river, then heeled her upstream and gave her a line. Landing downwind of the first mallard, her foolproof nose led her to the bird. She quickly swam back across the river with it. I let her rest a few minutes, then sent her again. The second greenhead took a bit longer, but she soon had it. That day I knew Bullet had made the passage from retriever-in- training to a seasoned veteran of the marsh.

These are the best of years. Your dog now operates like a well-oiled machine, and the long hours that went into training are a distant memory. Possessing separate strengths and skills, you and your dog mesh into an effective, economical team—a partnership portending bad news for ducks and geese. You’ve both worked hard to reach these glory years, and now it’s time to enjoy them.

Thumbing through my hunting journal, I found this brief entry: French’s Pond, October 7, 2004. Morning cold and clear. Paddled the canoe to a brushy island and put out a dozen mallard decoys. Good flight of dabblers until 10 a.m. Joe and I limited on mallards, pintails, wigeon, teal.

Those were the terse words of a tired hunter, scribbled before drifting off to sleep. But looking at them now, I can recall the stellar performance of my seven-year-old black Lab, Jenny, as if it were yesterday.

Shortly before sunrise a flock of mallards passed overhead, then turned and started back toward us, pushing into the breeze. As they angled down to the decoys, wings cupped, we tumbled three greenheads into the blocks. Jenny gathered them in. As dawn broke and the sun crept over a reddening eastern horizon, small flocks of mallards, teal, and pintails came and went. Jenny kept busy with the birds that stayed behind. One mallard dropped beyond gun range and dived repeatedly as she closed in, until she trapped it in the shallows.

About 9 a.m., a flock of high-flying wigeon cascaded toward the decoys, white wing patches twinkling in the sun. They dropped around us in a rush of wings and eerie whistles, the drakes’ white crowns clearly visible against a pale blue sky. Mesmerized, we blew holes in the air, managing to down only one bird.

I now had my limit, and Joe was one bird shy. While we debated picking up the decoys, six pintails arrowed in from the west, necks outstretched. A bird shuddered at Joe’s shot but sailed toward a line of cottonwoods marking the far edge of the pond. Jenny swam across, entered the trees and disappeared into the alfalfa field beyond. When she reappeared some time later, she had a lovely drake pintail in her mouth. We ended the morning with no birds lost, thanks to Jenny, a retriever in her prime.

Brothers and Sisters, I bid you beware

Of giving your heart to a dog to tear.

Rudyard Kipling

There comes a time when age and circumstance dictate that your old retriever must be retired because of arthritis, deafness, cataracts, or a host of other ailments. But the old dog still gets restless when autumn nights grow brisk; he rises unsteadily to his feet, tail wagging, at the sight of your decoys or shotgun. “I can still go,” he seems to say, a look of pleading in his eyes. But he can’t go. He may not know it, but you do. Hold him close, stroke his graying muzzle, and treasure him. He’s earned your respect and love.

Before that day comes, though, there will be a time and place, before the ponds and sloughs ice up around the edges, for an old dog to join you in the field. At age eleven, my black Lab Maggie still enjoyed good health. She had retrieved most of the ducks and geese native to the northern plains, but she’d never retrieved a canvasback, the king of ducks.

I had a plan to remedy the situation—a plan involving a trip to a wildlife management area in west-central Montana. When the wind blows hard across this shallow prairie wetland, as it often does, the ducks leave open water to seek sheltered nooks and coves. On such days, a well-positioned hunter can profit.

Maggie and I made the trip in late October, arriving an hour before dawn. I pulled on hip boots, grabbed my gun, shells, and a bag of decoys and began the long walk across a dike toward the main lake. After placing the decoys off the tip of a point that juts into the lake, we settled into the grass to await first light.

As dawn arrived, I could see, in the distance, flocks of ducks winging over the marsh. Ragged clouds scudded across a slate gray sky. The prairie wind sang through the grass and over the lake, raising a chop on the dark water. An occasional squadron of divers followed the lakeshore, just out of shooting range.

Engrossed in watching a wavering line of tundra swans out over the lake, their mournful cries rising and falling on the wind, I nearly failed to see the wedge of ducks coming straight toward me along the shoreline. On they came—big, powerful ducks with white bellies, looking like silver bullets tipped with rusty red. Cans! The nearest drake dropped to the water at my shot. His head was up, so I shot again to make sure he wouldn’t dive. A wounded canvasback might lead an old dog on a long, exhausting chase.

When I yelled “Fetch!” Maggie hit the water and closed in fast on the lifeless bird. She paddled back slowly, as if savoring the moment, and met me at the shoreline, holding the regal drake proudly. After a rest, we began the hike back to the truck, to a dry towel and warm heater.

Thanks, Maggie, for the canvasback. You’ve been gone many years, but when I close my eyes I can still see you bringing in that duck. Thank you, Bullet and Jenny, for all the good times. You were funny, loyal, brave, and smart, not to mention good at your job. I miss you. And thank you, Bailey, for bringing me the pinecones … and the apple … and for letting go of the skunk. I have a feeling great days lie ahead for you and me.