I WAS WOKEN what seemed like only moments later by the sound of a piano playing and the unmistakable smoky-sweet stench of Russian tea. I wasn’t sure if I was dreaming or if Ron had arrived early at the office. Knowing Ron, this seemed highly unlikely; and sure enough, when I half opened my eyes I saw that it was in fact Morley, Morley with his moustache and his grin, Morley seated at Ron’s piano, singing and strumming a song in a minor key.

Once I built a railroad, I made it run

Made it race against time

Once I built a railroad, now it’s done.

Brother, can you spare a dime?

Once I built a tower up to the sun

Brick and rivet and lime

Once I built a tower, now it’s done

Brother, can you spare a dime?

‘Ah, Sefton, good morning!’ He raised his cup of tea towards me in greeting.

I was about to reply when there came a horrible sharp dinning in my right ear: I wondered for a second if I had perhaps burst an eardrum after my fall down the stairs. I hadn’t: it was just Miriam, with a trumpet to her lips, attempting some sort of reveille.

‘How did you find me?’ I managed to ask them, through my confusion.

‘Really, Sefton. It doesn’t exactly take a Miss Marple to track your movements,’ said Miriam. She laid down the trumpet and was about to pick up a trombone.

‘I’ve got a bit of a headache, actually,’ I said.

‘I’m not surprised. You look dreadful. What on earth’s happened to you? Have you been in another fight?’ I saw that her eyes had alighted upon the xylophone in the corner.

‘Please,’ I said. ‘I really do have a—’

‘Well, if you will insist on drinking and carousing, Sefton, what on earth do you expect?’

‘A most singular method of enjoying oneself, if you don’t mind my saying so,’ added Morley. ‘Not at all good for one. The old ivory dome.’ He tapped a finger to his head. ‘One has to take care of it, you know. I was at Madison Square Garden when Max Baer beat Primo Carnera – goodness me, that was a fight. Couldn’t you take up chess instead? Do you know Max Euwe?’

‘I can’t say I do,’ I said.

‘World champion? Defeated Alekhine?’

‘I must have missed that,’ I said.

‘Good dose of Eno’s Fruit Salts will see you right,’ said Morley.

‘Mmm,’ I agreed.

‘Or this,’ said Miriam, and she thrust her left wrist under my nose. ‘Have a sniff. It’s Schiaparelli’s Shocking. My new scent. Given to me by an admirer. Do you like it?’

I took a quick sniff. It smelled like all other perfume.

‘Well?’ said Miriam.

‘Very nice,’ I said, finally beginning to gain full consciousness.

Miriam and Morley certainly had a way of waking a man up in the morning.

Morley was opposite, at the piano, looking as spruce and as chipper as ever: bow tie, light tweeds, dazzling brogues. Miriam was doing her best to lounge on Ron Pease’s office chair – and her best was more than good enough. She somehow looked at this unearthly hour as she always looked: as though she had just finished a photo-shoot, perhaps for Vogue magazine, or some publicity stills for MGM. Her eye make-up was fashionably smudged, her white dress and matching jacket exquisite. She was also sporting some sort of barbaric necklace that looked as though it might recently have been wrenched from the neck of an aboriginal tribesperson, and then set with diamonds, the sort of necklace that one sometimes sees in the window of Asprey – the sort of necklace that might cost at least one hundred pounds or more.

I put the thought immediately from my mind.

‘Who let you in?’ I asked.

‘Well, it’s a surprisingly busy little building, isn’t it?’ said Morley. ‘A charming young lady from the first floor escorted us up. I think she said her name was Desiree?’

‘I think you’ll find her name is probably not Desiree,’ said Miriam, looking knowingly at me.

‘Sorry?’ said Morley.

‘“That one may smile, and smile, and be a villain – At least I am sure it may be so in Denmark.”’

‘Hamlet?’ said Morley. ‘I can’t see the relevance, my dear.’

‘Denmark. Street,’ said Miriam.

‘Anyway,’ I said.

‘Yes, quite,’ said Morley. ‘Anyway. No time to lose, eh, Sefton? Another book to write.’

‘Sorry, did we finish the last one?’

‘Yes, we did,’ said Miriam.

‘Westmorland,’ said Morley. ‘Almost finished.’

‘In your absence,’ said Miriam.

‘Few tweaks, few i’s to dot and some t’s to cross, but we should have it done by the end of next week, Miriam, shouldn’t we?’

‘I would have thought so, Father, yes.’

‘So, ready for the printers and into the shops by the end of October, I would have thought. Excelsior!’

‘Right,’ I said.

Morley was publishing books almost faster than I could read them. I’d been in his employ since early September, working on The County Guides, and we’d already covered Norfolk, Devon and Westmorland. I’d travelled more widely in England within a month than I had in the previous twenty-six years of my pre-Morley existence.

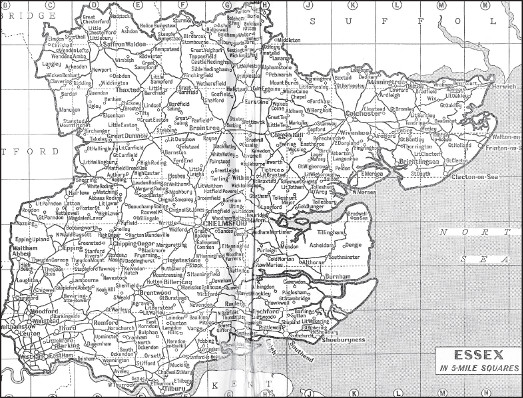

‘You’ll be thrilled to hear, Sefton, that our next county is Essex,’ said Miriam.

‘Essex?’

‘That’s right,’ said Morley. ‘When you think of Essex, Sefton, what do you think of?’

‘When I think of Essex.’ When I think of Essex? It was not a place I had ever given a first – let alone a second – thought to. ‘When I think of Essex I think of …’ I thought of Willy Mann asking if I’d like to work for Mr Klein on some project.

‘Oysters!’ said Morley. ‘Correct! And cockles, sprats, whitebait, flounder, dab, plaice, sole, eels, halibut, turbot, brill—’

‘Yes, Father, we get the picture.’

‘Lobster, haddock, whiting, herring, pike, perch, chub—’

‘Yes, Father.’

‘Gudgeon, roach, tench—’

‘Father!’

‘Winkles. But above all the Ostreaedulis! The English native!’

‘Sorry? The English native …?’

‘Oyster, Sefton! It is our privilege, sir, to have been invited as guests of honour to the annual Oyster Feast in Colchester!’

‘Very good,’ I said.

‘Colchester, ancient capital of England. Camulodunum – the fortress of Camulos! A place arguably more important historically than London itself. Home to the mighty Coel and his daughter Helena, not to mention the mighty Boadicea.’

‘And tell him, Father.’

‘Tell him what, Miriam?’

‘Father’s terribly excited, Sefton, because one of the fellow guests at the Oyster Feast is going to be—’

‘Oh yes!’ cried Morley. ‘The aviatrix!’

‘The who?’ I asked.

When I think of Essex

‘The aviatrix!’ repeated Morley.

‘By which he means the famous female aviator Amy Johnson.’

‘Really?’

‘Apparently, according to Father.’

‘Well, I very much look forward to—’

There came the sound of bells ringing outside. St-Giles-in-the-Fields. This was one of the disadvantages of staying at 14 Denmark Street: the close proximity to Christian bell-ringing, which could play havoc with a hangover, though frankly Morley and Miriam more than matched the din. At the last stroke of the bell, Morley checked all his watches: the luminous wristwatch, the non-luminous wristwatch and his pocket-watch. He doubtless had an egg-timer concealed somewhere about his person, but there was no need to consult it on this occasion.

‘Not bad,’ he said. ‘Not bad. I’d better push on, though, chaps. I’ll see you there this evening?’

‘Father is travelling up by train,’ said Miriam. ‘We’re going to take the car. Now, I do expect to see you there on time, Father.’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘There’s an exhibition at the Royal Albert Hall,’ explained Miriam. ‘Father’s very keen to go.’

‘Ah,’ I said.

‘By the Ford Motor Company,’ said Morley.

‘At the Royal Albert Hall?’ I said.

‘That’s right!’

‘You’re not allowed to buy any more motorcars, though, Father. Understand?’

‘Yes, of course,’ said Morley.

‘We have quite enough already.’

‘Yes, yes.’

‘If you were going to buy another we’d have to sell one.’

Morley was an absolute car fiend. He was an autoholic. To my knowledge he never parted with a car, any more than he ever parted with a book, or a typewriter.

‘You’re just looking, remember?’

‘Yes, yes,’ said Morley. ‘I thought it was worth a visit,’ he explained to me. ‘Because we’re going to Essex. I tried to persuade Miriam that we should visit the Ford Works at Dagenham but she wasn’t keen.’

‘I thought Father going to an exhibition would be just as good. Don’t you agree, Sefton?’

‘Yes,’ I agreed. I probably had as little desire as Miriam to visit a motor vehicle manufacturer – probably less.

‘They’re bringing all the men and machines from Dagenham anyway,’ said Morley. ‘So it’ll be as if we were actually witnessing them constructing an actual vehicle in an actual factory!’

‘In the Albert Hall?’ I said. ‘Really?’

‘Yes, yes. Quite remarkable, isn’t it? Way of the future, Sefton. Arts, crafts and manufacturing joining together to usher in the Age of the Automated Arts. I wonder if we might organise some sort of society, actually … The AAA. Sort of an RSA for the twentieth century. What do you think, Miriam?’

‘I think we need to concentrate on the task in hand, Father.’

‘Yes, yes, of course. Very good. So, I have taken the liberty of drawing up a little list here of places in Essex for you two to visit on the way to Colchester, for the purposes of research for the book.’

He handed me a complicated diagram that looked as though it were a sort of geological map.

‘One needs to think of Essex, Sefton, as like a series of layers.’

‘Ah,’ I said.

‘Like a cake?’ said Miriam.

‘Precisely like a cake, Miriam,’ said Morley. ‘A sort of topographical cremeschnitte, in five parts: the coast, the marshes, the farms, the villages, and the towns dominated by London.’

‘OK,’ I said.

‘Our account of Essex will begin here, on the very bottom layer of the cake, as it were. In Becontree.’

‘Becontree?’ asked Miriam. ‘Must we?’

‘In years to come, Miriam, mark my words, Becontree will be regarded as one of the great wonders of the world. New housing for tens of thousands of workers? Quite extraordinary. Like something created by the pharaohs. It was a market garden at one time, of course. Now a sort of city planted on the Nile delta! A testament to the spirit of our age!’

‘Becontree?’

‘Fit for heroes, Miriam, remember. Fit for heroes! Think of yourselves as the companions of Columbus, setting forth to a New World, discovering the future!’

‘Becontree though?’ repeated Miriam.

‘Yes!’ insisted Morley, rather tetchily. ‘Now, some photographs of the Dagenham Borough Council building, Sefton, if you wouldn’t mind? Quite a thing, I’m given to understand. Early Saxon settlement, Dagenham.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes, Daecca’s home, I think.’

‘Right.’

‘I remember it as a village, of course.’

‘Very good.’

‘So, some sort of atmospheric shots of the great boulevards and avenues, if you would.’

‘The great boulevards of Becontree?’ said Miriam.

‘If you would, Sefton,’ said Morley, ignoring Miriam.

‘Certainly, Mr Morley.’

‘And on from the delights of Becontree, Father?’

‘Well, I thought we’d make a sort of clockwise journey, up from Becontree, to Romford, Brentwood, Chipping Ongar, Dunmow – Maid Marian laid to rest at Dunmow Priory, I believe. Some nice shots of Dunmow, Sefton. You know the story of the Dunmow Flitch of course?’

I must admit I had momentarily forgotten the story of the Dunmow Flitch.

‘A flitch of ham awarded to a married couple who can live without quarrelling for a year and a day.’

‘Ha!’ cried Miriam.

‘And then across to Colchester and back round via Manningtree – the Witchfinder General was from Manningtree, I believe. Full of witches, Essex.’

Miriam raised a finger and pointed at me. ‘Don’t you dare say a word, Sefton.’

‘I wasn’t going to,’ I protested.

‘Thank you, children. And then on to Clacton, Southend, etcetera, etcetera, further details to be confirmed. If we have time I’d very much like to call in on Margery and Dorothy, if Dorothy’s at home in Witham. She’s a bit of a gadabout. Margery’s bound to be there at Tolleshunt D’Arcy. We could hardly visit Essex without calling on the county’s two greatest living writers.’

‘Margery Allingham, Father?’

‘Yes.’

‘Oh no.’

‘What? Why? What’s wrong with Margery?’

‘She’s just a little … strange, Father, isn’t she?’

‘Margery?’

‘Yes.’

‘But she’s a writer, Miriam. And a very fine one at that.’

‘That’s no excuse, Father.’

‘Have you read Margery, Sefton?’ asked Morley.

‘No, I can’t say I have, Mr Morley.’

‘No? Goodness me, man. Sweet Danger is in my opinion one of the great detective books of this century!’

‘Really?’

‘Absolutely. You should read it immediately! I rate her rather more highly than Agatha, actually.’ Morley glanced around him, lowered his voice, and put a finger to his lips. ‘But don’t tell Agatha I told you.’

‘You have my word, Mr Morley.’

‘Dorothy’s fine though,’ said Miriam. ‘I don’t mind visiting Dorothy. She’s a hoot.’

‘The divine Miss Sayers,’ said Morley. ‘Now, she is a little strange, Miriam.’

‘I rather like her,’ said Miriam.

‘Well, of course you would, my dear: the most likeable thing about Dorothy is that she doesn’t care whether you like her or not.’

‘Exactly,’ said Miriam.

‘Anyway, social calls permitting, I think a couple of days should do it, shouldn’t it, for Essex?’

A couple of days chasing around Essex: another utterly lunatic enterprise, of course, just like all the others. But I had no reason to stay in London and every reason to get away. It would give me time to work out how to find a hundred pounds.

‘Great,’ I said.

‘What time is your train out of Liverpool Street later, Father?’ asked Miriam. ‘There’s a special train hired, for those invited to the Oyster Feast, Sefton.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes,’ said Morley. ‘Same every year, apparently. Tradition. Very good of them. And quite appropriate – in a sense Essex begins and ends at Liverpool Street Station, don’t you think?’

‘Indeed it does, Father,’ said Miriam. ‘Indeed it does. The rot sets in almost as soon as one leaves the station. Before, in fact. It’s a perfectly horrid place.’

‘I quite agree with you about Liverpool Street Station, my dear, but I think you’ll find you’re entirely wrong about Essex. Entirely lacking in the great beauty of Devon, of course, or indeed the wildness of Westmorland, or the sheer splendour of Norfolk, but it does make the most of what little it’s got.’

‘Hardly a recommendation, Father.’

‘Anyway,’ said Morley. ‘Must run!’

‘The time, Father, of the arrival of your train?’

‘I’ll send you a telegram,’ said Morley.

‘To where?’ said Miriam. ‘We’ll be in the Lagonda. And you’ll be on the train.’

‘Ah,’ said Morley. ‘Good point. You know, one day someone needs to invent some kind of mobile communication device. A sort of pocket telegram machine.’

‘I’m not sure it’d catch on, Father.’

‘Perhaps not,’ said Morley.

‘It would just involve people telling each other they were on board trains.’

‘Ha!’ said Morley. With which he got up from the piano stool and dashed for the door. ‘Good luck then, you two. Until we meet again in Essex!’

‘Very good,’ said Miriam. ‘Goodbye, Father.’

‘No slacking,’ he called from the corridor.

‘No shilly-shallying,’ replied Miriam loudly.

‘No funking,’ I mumbled.

‘Although …’ said Miriam, turning towards me, and adopting her lounge position on the chair. ‘While the cat’s away the mice shall play, eh, Sefton?’

I needed a cup of coffee and a pick-me-up.

And a hundred pounds.