I CAN ONLY DESCRIBE THE SCENE that we eventually came upon in Colchester as ‘strange’. (Morley, I should say, did not like the word ‘strange’. He regarded it as lacking in specificity, ‘a terrible failing in a word’ – see Morley’s Vocabulary Builder: Words to Use and Words to Avoid (1932) – as if it were somehow its own fault.)

Morley’s ambitious itinerary for our trip up through Essex suggested that after Becontree we were supposed to visit Epping Forest (‘Poor John Clare!’ read his scribbled notes. ‘Mad as a hatter!’), Romford’s famous brewery, Tiptree for the jam, the villages around Saffron Walden (‘Cromwell’s headquarters – the heart of Radical Essex!’), the Marconi works in Chelmsford (‘Inventive Essex!’), before finally heading to Colchester for the Oyster Feast. But after our tour with Willy Mann of the jerry-built houses of Becontree we were forced to cut short our peregrinations and to press on directly to Colchester to make it in time for the Oyster Feast. Miriam, needless to say, drove like a maniac. I shan’t even attempt to describe the Essex countryside: it all looked perfectly pleasantly blurred.

And it got blurrier. The Lagonda had started juddering and had picked up a distinct knocking sound somewhere just past Ongar.

‘What’s that?’ asked Miriam, above the sound of the roar of the engine.

‘I’m not sure,’ I said. ‘We should stop and get it looked at.’

‘It’s probably fine,’ said Miriam. ‘It’ll stop in a minute.’

It didn’t stop in a minute. Or indeed in five or in ten minutes.

‘I really think we ought to stop, Miriam.’

‘We are not stopping,’ said Miriam.

‘I think we should.’

‘You can think what you like, Sefton. I am not going to miss the Oyster Feast for the sake of some pathetic grumbling engine, thank you,’ said Miriam.

‘You may not have a choice, Miriam,’ I said.

‘Well you see, that’s the difference between us, isn’t it?’ said Miriam, looking at me pityingly, with one of her hard-edged sideways stares. ‘You don’t seem to understand that there is always a choice, Sefton. And this,’ she continued, stamping her foot violently on the accelerator, causing the car to jolt forward, ‘is my choice.’

Essex was jerked out of my vision. The Lagonda kept making its unhappy sounds and Miriam kept on thrashing it mercilessly. I made one last attempt to intervene.

‘The Lagonda is a very finely balanced car,’ I shouted, somewhere around the Rodings. ‘If you don’t treat it right you’re going to end up doing it serious damage.’

‘And I Am a Very Finely Balanced Woman, Sefton,’ yelled Miriam back at me. ‘And exactly the same applies.’

Controlling the Lagonda with sheer willpower, and not inconsiderable strength, she pushed it to the very limits, tearing through the roads of Essex towards Colchester, slow into corners, fast out, continually over-revving – a terrible habit of hers – until somehow we all arrived in one piece. Just. The car smelled of misery and burned fuel. It would clearly require some serious mechanical care and attention, but Miriam didn’t care. She was triumphant: she’d taught the machine obedience; she’d shown it who was boss.

‘See,’ she said. ‘I told you it’d be fine. Come on then. Let’s not hang around, now we’re here. We have oysters to eat!’

We had parked some distance away from the centre of the town, there being roadworks everywhere; it seemed like every street was being dug up at once. Despite her admonitions to me, Miriam spent a long time carefully reapplying her make-up in the car and then changing into evening wear – a scarlet gown with green evening coat and long black gloves – which was no mean feat, even on the accommodating and well-appointed back seat of the Lagonda, the outfit requiring much energetic wriggling and a helping hand with the zip. (With my eyes shut tight, I should say – which was also no mean feat.)

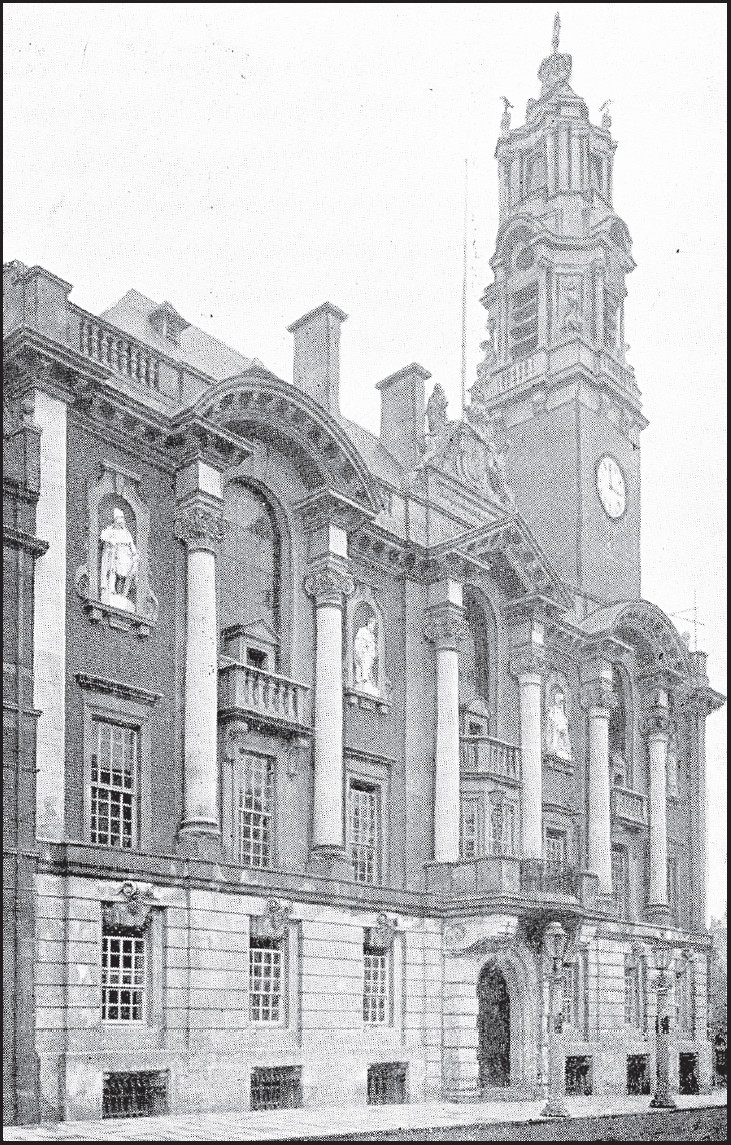

We then left the poor vehicle and trudged up a steep hill amid a crowd of men, women and children who were most definitely not dressed in evening wear but who were all busy consuming roasted chestnuts and cramming themselves into the streets around Colchester’s magnificent Town Hall, a vast and bewildering building that had all the appearance of a stout English yeoman’s version of a Venetian palazzo. ‘A fine example of Victorian baroque,’ according to Morley in Essex. ‘Built between 1898 and 1902 for the princely sum of £55,000, making it one of the most expensive public buildings in England, Colchester’s Town Hall contains many offices, grand public rooms, the magnificent mayor’s parlour and of course the famous Moot Hall, the whole thing topped off with a huge and ornate tower that is in effect a giant gauntlet thrown down to the town’s upstart rival, Chelmsford.’

Morley was a great fan of Colchester’s rather strange and aggressive architecture, controversially describing the town in The County Guides not as ‘picturesque’ but rather as ‘picaresque’, a ‘town that seems to invite adventure’. As well as the Town Hall, and the presence of so many Roman ruins, and the barracks – all of which contributed to the town’s peculiar air of menace – there was also the presence of Jumbo, the vast building in the centre of the town, which dominates the skyline much as the Empire State Building dominates New York, or the Eiffel Tower Paris, the only difference being that Jumbo is not a world-famous tourist attraction or a state-of-the-art office building but an enormous, ugly, red brick water tower. Built in the late 1800s, the building apparently received its nickname from a local clergyman, whose rectory fell beneath its enormous shadow. ‘If not exactly one of the seven modern wonders of the world,’ writes Morley of Jumbo in The County Guides, ‘then it is most certainly one of the seven modern wonders of Essex.’ He did not specify the other six.

Dusk was falling and Jumbo was brooding as Miriam and I came to a halt before the Town Hall. We could go no further: the crowd was too dense. Above the sound of mass roasted-chestnut munching came a low moaning sound in the distance; Miriam raised one of her expressive eyebrows at me and asked if I knew what it was.

A giant gauntlet

The upstart rival

‘I think I know what it is,’ remarked some wag standing next to us in the crowd. ‘I hear it once a week, regular as clockwork, on a Saturday night when I get home from the pub. That’s the good old sound of an Essex girl, if you know what I mean, miss.’

Miriam, thank goodness, did not respond in kind to this crude provocation and fortunately the moan soon became a drone and eventually a definable tune: it was in fact the sound of the Dagenham Girl Pipers.

The Dagenham Girl Pipers. According to Morley in The County Guides: Essex, nothing sums up the odd, eccentric spirit of the county more clearly than the Dagenham Girl Pipers. For anyone who has never been lucky enough to see the actual kilted Cockney sparrows in full fig and full flow all I can say is that their name is an entirely complete and proper summary. They are from Dagenham, they are girls, and they are pipers – facts and states that in and of themselves are of course unremarkable, but as Morley always liked to say, there is nothing new under the sun, except in combination. Formed in 1930 by Reverend Joseph Waddington Graves – ‘lovely man,’ according to Morley, who had interviewed him for some newspaper or other, ‘Canadian, absolute loon’ – the Dagenham Girl Pipers initially consisted of just a dozen keen young girls from his Sunday School but within a few short years they had become a fully professional touring troupe who skirled their way round Europe in their distinctive Royal Stewart tartan.

They are from Dagenham, they are girls, and they are pipers

The crowd burst into applause as the girls appeared at the bottom of the road in their fabulous costumes – kilts, tartan socks, black velvet jackets and tam o’ shanters – bellowing on their bagpipes, a vision guaranteed both to haunt and delight even the hardiest and hardest-hearted onlooker, perhaps even a Scot, and all illuminated by the town’s remarkable bright modern street lighting, which made it look as though the girls were performing on a West End stage, rather than a tarmacked Essex street in early autumn.

‘Those lassies certainly know how to blow,’ remarked the wag standing by us, as we all watched the girls, utterly entranced, as they marched up to the Town Hall, promptly stopped blowing, laid down their pipes, and launched into a complex choreographed reel and sword dance.

‘Don’t they just,’ said Miriam. ‘And they know how to move. A winning combination, I would say.’

If anything, the evening then got even stranger. Following the Dagenham Girl Pipers came a procession of schoolchildren wearing papier mâché shell heads, a troop of Lancers from the local barracks on their horses, the band of the 1st Royal Munster Fusiliers banging out ‘The Men of Merry England’, and a long solemn line of dignitaries, including Morley, who didn’t spot us waving and shouting frantically in the crowd. This motley crew paraded up to the doors of the Town Hall and disappeared inside.

‘Now what?’ asked Miriam.

‘Now they all go and get drunk on our money!’ said the man standing next to us.

‘Well, we’d better go and join them, hadn’t we, Sefton?’