MIRIAM, NEEDLESS TO SAY, loved the Cadillac and certainly seemed to agree with Morley that it was indeed a kind of mechanical aphrodisiac: she insisted on referring to it, alas, as her ‘Yankee toy’. She spent an inordinate amount of time merrily and pointlessly revving the engine outside the George Hotel, in absolute ecstasy, causing quite a hullaballoo: the roar she managed to coax from the thing was really quite extraordinary, like an animal in heat.

‘She was just the same when she got her first pedal car,’ said Morley, who was momentarily distracted with yet more articles to file – a piece on spade mills for some guild newsletter or other, and a short piece on Maimonides for the Jewish Chronicle, all of which he somehow managed to write, edit and dispatch in the time it took me to rustle up a flask of tea and some dry biscuits from the hotel kitchens – but eventually we set off shortly before lunch for the famous oyster beds on the Essex coast.

While Morley and I had spent the morning sorting out the Lagonda and procuring the Cadillac, Miriam had been busy catching up on all the local news and gossip. This was her forte. She was capable of eliciting information – and, frankly, almost anything else – from anyone. Apparently there had been no other fatalities from the oysters at the Oyster Feast and those who had been admitted to hospital had been released.

‘Crowd hysteria,’ said Morley. ‘As I said.’

‘Yes,’ agreed Miriam. ‘It does seem that poor Mr Marden really was just terribly unlucky.’

‘Heart attack?’ said Morley. ‘Possibly. Could have been anything.’

‘One bad oyster, possibly?’ said Miriam.

‘Nonsense,’ said Morley. ‘One bad oyster, out of however many thousand being eaten at the feast, and poor Marden’s on the receiving end? Statistically highly unlikely.’

‘Well, whatever it was, it was jolly bad luck anyway,’ said Miriam, as if Marden had just been dealt a bad hand in a game of whist.

‘Indeed,’ agreed Morley, though of course he did not believe in luck, good or bad, in cards or in anything else. (For full details of his ideas about luck see his much reprinted article ‘Get Lucky’, which first appeared in the London Gazette on 24 October 1931, and which has been variously plagiarised, summarised, rephrased, represented and otherwise regurgitated by many others and indeed by Morley himself ever since. In summary: according to Morley, good luck is a skill, and bad luck simply the product of poor choices and overlooked opportunities. In other words, tough luck. He always had a touch of the Samuel Smiles about him.) Fortunately he did not seem to be in the mood for a discussion about the meaning of the mayor’s good or bad luck. The poor man was dead, after all, and that was that. And we had work to do. ‘Come on!’ he said, as we finally left Colchester. ‘Essex won’t write itself, you know.’

As we left Colchester in the Cadillac I glanced up, half expecting to hear the overhead chugging of Amy Johnson in her Gypsy Moth, waving us goodbye. But there was nothing. She’d gone. I patted her silver cigarette case in my suit pocket.

At high noon the vast salt marshes and intertidal mudflats of the Essex coast have the most strange and spectral appearance – almost as if one were in a desert approaching an oasis. It is a landscape without figures which forever promises mystery, misery and – most likely – fog. Distant creeks coil around dozens of uninhabited low-lying islands covered with lilac sea lavender and both land and water seem never-ending. Morley of course was absolutely in his element, imagining the place as it might once have been, when England and France were joined by land and mammoths roamed the marshes. He insisted that I make notes on all sorts of passing items of interest: the occasional cabin and poor dwelling, the wildlife, rose hips, samphire, faint evidence of ancient settlements. Starlings. Swallows. The white corona of the sun, which looked vaguely dyed yellow, apparently, and which reminded him of the colour of one of his favourite canaries … The conversation was as strange and as spangly as ever, Morley merrily riffing, for example, on the theme of Roman Colchester.

‘Do you know, for all their achievements, what we really have to thank the Romans for, Sefton?’ he asked, as we sped along.

‘Aqueducts?’ said Miriam, who was not one to be bested, even on very general questions of general knowledge.

‘No, no, no,’ said Morley. ‘Not aqueducts, Miriam, absolutely not. Common misapprehension. We have the Greeks and Assyrians to thank for the development of aqueducts, I think you’ll find.’

‘Sanitation?’ I said.

‘Ancient India!’ said Morley. ‘Plenty of it there, thank you very much. Highly sanitised race, the Indians. Years ahead. We have the Harappans to thank for the development of public health and sanitation, Sefton, not the Romans. Are you quite up to date on your ancient cultures and civilisations? Does a Cambridge education not equip a man with such knowledge?’

Apparently not. My grasp of ancient cultures and civilisations was clearly not what it might have been. The Harappans? Who on earth were the Harappans?

‘The roads, Father?’ said Miriam. ‘Didn’t the Romans give us roads?’

‘Hmm, close, my dear, yes, close, roads. Straight strong stone roads certainly. But what about the ancient log roads of Europe, eh? And animal tracks and trails? I fancy the history of the road began long before the Romans, long long ago in Ancient Egypt. And India. And China of course.’

‘Irrigation, then?’ said Miriam, with some annoyance. ‘Medicine? Education? Wine? Public order? All or any of the above?’

‘Mesopotamia, China, China, China again, and – guess what? – China. Remarkable culture really, isn’t it?’ said Morley. ‘I wonder if there might be a book in it, you know? What the Chinese Did For Us?’

‘We have more than enough books on our hands at the moment, Father,’ said Miriam. ‘Don’t forget there’s that book of folktales you’re supposed to be editing. And that history of tartan.’ It was down to Miriam to manage Morley’s massive output – a management task that was in itself far beyond most human capacities, never mind Morley’s actual endless production of the stuff, which was unimaginable.

‘Ah, yes, the tartan book; I wonder if I can get something in about the Dagenham Girl Pipers?’ said Morley.

‘I’m sure you can, Father. I’m sure you can. But we must focus first on the task in hand, mustn’t we?’

‘Of course, my dear. What were we talking about?’

‘China?’ I said. Miriam shot me a glance of disapproval.

‘Yes! Yes,’ said Morley, returning to his theme. ‘We underestimate the Chinese at our peril, Sefton. In years to come, mark my words, China will once again be the world’s greatest empire. The Soviet Union will seem quite puny in comparison. Never mind the Roman. So …’ He looked up from his notebook for a moment. He was always making notes: writing, drawing, making calculations. There are indeed many many more notebooks than there are books – a treasure trove for future scholars. (And for future reference, as I’ve often had to plead: please do not write to me, write to the estate, c/o Morley’s London agent.) ‘Do you want me to tell you?’

‘Tell us what, Father?’ said Miriam.

‘What was the most important thing that the Romans ever did for us?’

‘Oh yes, do,’ said Miriam. ‘Because I think I can safely say that we’re totally fed up with this game now, aren’t we, Sefton?’

‘Well …’ I said, havering. I probably spent half of my working life with Morley totally fed up and the other half amazed. It was a reasonable percentage.

‘You really want to know the most important thing that the Romans ever did for us?’ said Morley.

‘Yes!’ said Miriam. ‘Do get on with it, Father.’

‘The most important thing that the Romans did for us was …’ Morley paused for effect. ‘The cultivation of oysters in brackish pools near their centres of settlement, of course!’

‘Oh,’ said Miriam. ‘How disappointing.’

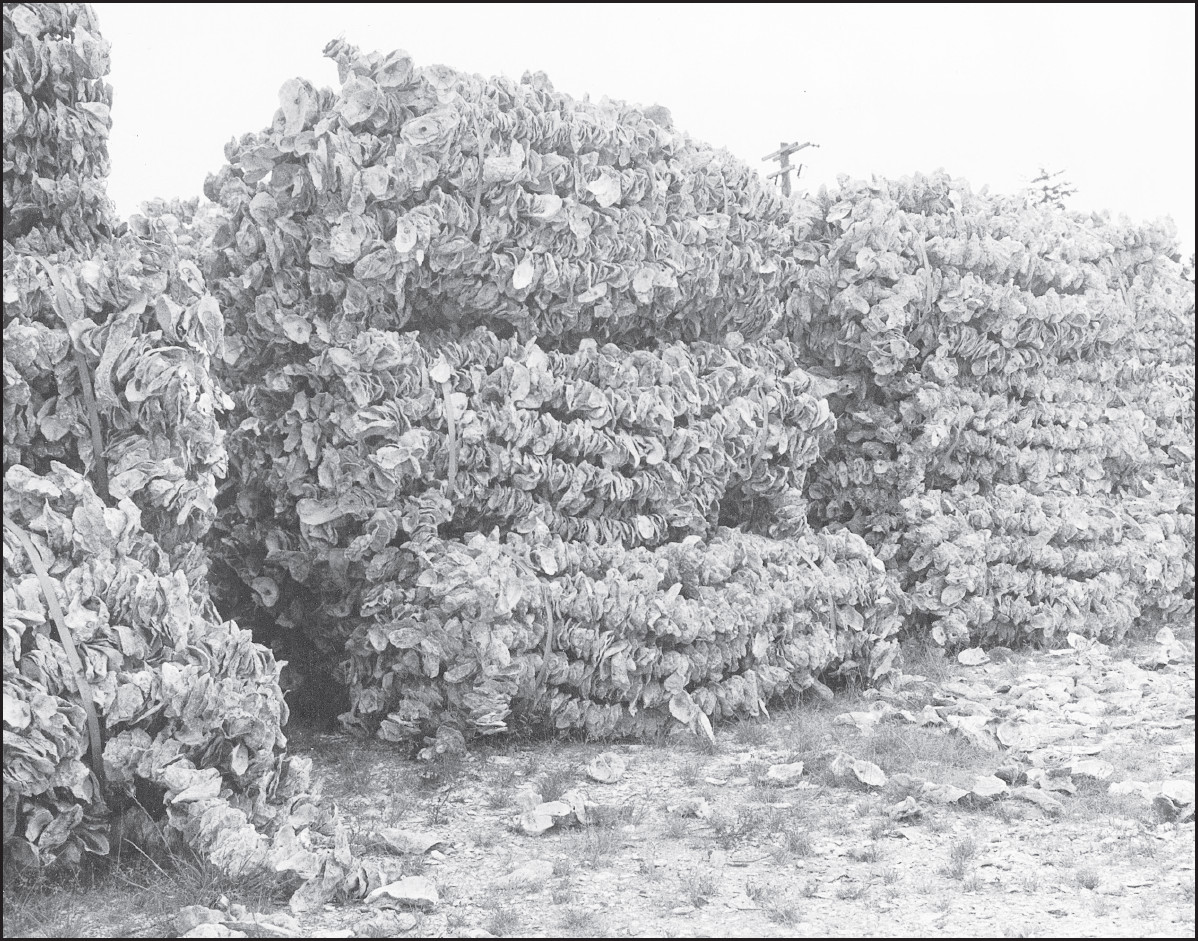

![]()

We arrived eventually in West Mersea, which is a place that specialises in the cultivation of oysters in brackish pools, and which is indeed rather disappointing, the kind of place that it’s hard to believe still exists in modern England. One doubts it could exist for much longer, if it still exists at all, that is. It had all the appearance of a remote fishing village in the Highlands of Scotland or in Nova Scotia. Beyond the few houses and the chapels, the church, there were dozens of rather decrepit buildings clustered down by the beach that at first appearance seemed to be made entirely of salvaged materials – weatherbeaten planks, rusted iron and so on – and which on closer inspection turned out actually to be made entirely of salvaged materials. The place had all the aspect of a coastal slum.

Some oyster shells

‘Marvellous!’ said Morley, as we clambered out of the Cadillac, having parked in a muddy patch of ground by the largest of the buildings. ‘Look at this! Human ingenuity in the face of nature’s onslaught!’

‘Oh God,’ said Miriam, pulling off her driving gloves and lighting a cigarette. ‘Not what I expected at all. Absolutely dismal, isn’t it?’ It was always impossible to know exactly what Miriam expected, though she always expected better, and dressed accordingly. Today she had gone for a nautical look, a silk dress in blue and white with a high belted waist, capped sleeves and bow collar, accessorised – as she liked to say – with a sailor’s cap and white patent leather heels. Miriam and her outfit would probably have looked perfectly the part in a cool breeze on a yacht on a summer’s day in the south of France. They were perhaps a little de trop in West Mersea in October.

‘Cut on the bias,’ she confided to me, when she caught me admiring her in the dress, though I had absolutely no idea what that meant. ‘Rather flattering, isn’t it?’ I couldn’t deny it.

Morley knelt down and took two handfuls of what appeared to be muddy gravel.

‘As I thought!’ he said, straightening up. ‘Look at this, Sefton.’

I looked. ‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Well?’ he said.

‘Muddy gravel?’

‘Crushed and ground oyster shells!’ he exclaimed. ‘Marvellous! Used to be used as aggregate, of course, by the Romans. Very useful building material. Only trouble is, the buildings made from it tend to collapse.’ He allowed the oyster shell gravel to run through his fingers. ‘Anyway, lead on, Miriam!’

‘Lead on, Macduff!’ I said, in an attempt to ingratiate myself with the pair of them, with a little Shakespearean allusion of my own.

‘It’s “Lay on, Macduff,”’ said Miriam.

‘Spoken by Macbeth,’ said Morley.

‘“And damn’d be him that first cries, ‘Hold, enough!’”’ added Miriam. ‘Meaning, roughly, let’s fight to the death, before of course Macduff kills Macbeth in combat. Entirely appropriate?’

‘Good try, though,’ said Morley. ‘Keep at it, Sefton. You’ll get there.’

I was getting nowhere.