Chapter 3

Four Steps to Freedom

The Process of Recovery from Chronic Loss

“It is true that as long as we live we may keep repeating the patterns established in childhood. It is true that the present is powerfully shaped by the past. But it is also true that . . . insight at any age keeps us from singing the same sad songs again.”

—Judith Viorst, Necessary Losses

“It is not possible to be honest in the here and now when you continue to discount and minimize your childhood experiences.”

—Claudia Black

FOR ADULTS FROM TROUBLED FAMILIES who turn to a new course for their lives, the process of recovery brings renewed energy, new understandings, and new hope.

• Recovery is actively taking responsibility for how you live your life today.

• Recovery is being able to put the past behind. It’s no longer having your childhood script dominate how you live your life today.

• Recovery is being able to speak the truth about your growing up years.

• Recovery is the process in which you develop skills you weren’t able to learn in your childhood.

• Recovery is a process, not an event, often beginning as a result of a professionally directed treatment or therapy, or experiences in self-help groups.

• Recovery is no longer living a life based in fear or shame.

• Recovery is developing your sense of self separate from survival/coping mechanisms. Your identity is no longer based in reaction, but action.

• Recovery is the process of identifying, owning, and developing healthy ways of expressing feelings; it is the process of learning self-love, self-acceptance. From learning these new ways, a person often learns how to set healthy boundaries and limits, to get needs met, to play, relax, and develop flexibility.

• Recovery is the process of learning to trust yourself and then trusting others, and with trust comes the opportunity for intimacy.

A person is truly on a recovery course when new belief systems and new behaviors are actualized in relationships at work, with friends and family, in the most intimate love and sexual relationships, and in taking care of oneself physically and emotionally.

People reach their turning points in different ways. Some begin in Twelve Step programs, others through their religious beliefs, through spiritual healing, and/or professional therapy services. Whatever brings you to your new beginning, you will need to attend to some core issues from your past, so that they no longer dictate how you live your life today.

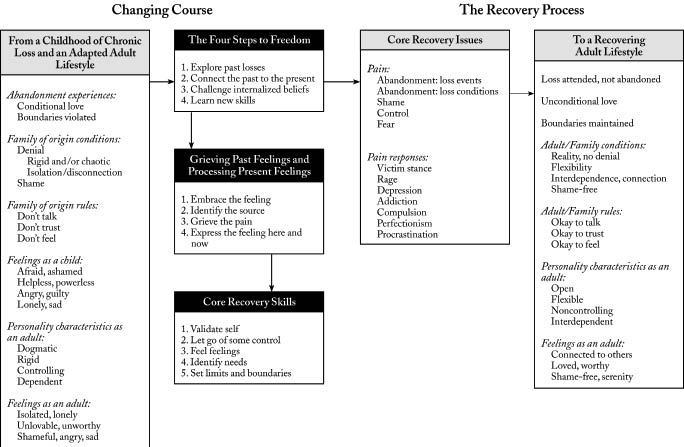

In chapter 2 we looked at the general causes and the dynamics of past pain: chronic loss, abandonment, fear, and shame. You will need to identify the specific events and conditions in your own life, those that were played out in your past, and those that continue to cause pain in the present. To resolve your feelings and revise your beliefs and re-learn behaviors, you will need to incorporate four identified, important steps that are the backbone of the recovery process. Each time you face a particular issue, you will need to go through all four of these steps.

Four Steps to Recovery

Step One: Explore past losses.

Step Two: Connect the past to present life.

Step Three: Challenge internalized beliefs.

Step Four: Learn new skills.

The steps to recovery, along with the feelings, processes, and skills needed, are illustrated on the chart, “Changing Course: The Recovery Process.”

Step One: Explore Past Losses

“What Happened That Hurt Me?”

“What Didn’t I Have That I Needed?”

Much of the initial part of the recovery process involves talking about the past. Many people find this both exciting and scary, but some wonder why it is necessary. As I mentioned earlier, if recalling something from the past feels like you have to “drag it up,” there is almost always unresolved pain attached to the experience that still affects you today. Clearly, the purpose of talking about the past is to put it behind us.

To let go of the past you must be willing to break through your denial so you can grieve your pain. In other words, you have to admit to yourself the truth of what happened, rather than hide or keep secret the hurt and wounds that occurred. Admitting the truth is not meant to be a process of blaming our parents. In fact, as we go back and explore the past, we may not even choose to share the information with our parents. Whether or not you do is a very individual matter.

One does not explore the past to assign blame but to discover and acknowledge reality. Very often adults still operate on beliefs formed in childhood. Looking back at specific past events may cause a major shift in perspective. For instance, if our parents had hit us in anger, our childhood assumption was that they were angry at us for something we did wrong or that we were inadequate in some way. As adults we can see that our parents were really angry with themselves, or angry about something else in their lives, a job loss, for example. As vulnerable children we were easy targets, so we were the ones who were hit, but for entirely different reasons than we believed.

Our newly acquired understanding is a critical step in the process of creating positive beliefs about ourselves. However, acknowledging the reality, in this case that our parents hit us, is also essential. We can no longer afford to be held hostage by this shameful secret. Acknowledging the reality of what happened allows us to feel and grieve the pain.

Exploring the past is very important because it may be the first time in our lives that we have been able to talk openly about our experiences. As we complete our loss graphs we will be able to identify those specific events and conditions that caused pain and restricted our lives. Talking without the fear of being rejected or punished allows us to release deep feelings that we have kept inside and that remain hurtful to us. When we do this with other people participating in the same process, we receive validation for who we were when we were young. The word validate comes from the Latin valere, “to make strong.” Being validated makes us strong.

Most of us who grew up with chronic loss need to talk with others about our experiences to help us recognize our needs and to learn how to set appropriate limits and boundaries. We will be able to discard the messages that we aren’t good enough or that we are inadequate. Then we begin to understand that we are of real value. This should not be an isolated process. Sharing our painful experiences with others who understand creates a needed support system.

A major purpose in going back and talking about the past is to break the denial process and start speaking the truth. It’s difficult when you’ve had to deny, minimize, or discount the first fifteen or twenty years of your life. While denial became a skill that served you as a child in a survival mode, its continued use today interferes in adult experiences. When you have worked through this process you can begin to learn to be honest about what is occurring in the present, in the here and now.

As an adult, it is easy to continue to minimize, discount, rationalize, but these are behaviors that block the honest identification and expression of feelings. They impede your ability to be honest with yourself and others. This greatly impacts self-esteem and interpersonal relationships. Owning your experiences in childhood greatly relieves the burden of defending yourself as an adult and gives you a beginning of “choice.” Exploring the past is an act of empowerment.

The Process for Healing Feelings from the Past

As we discover and acknowledge painful realities in our past we are, at the same time, doing our “grief work.” We are identifying and grieving the losses that occurred in our lives. Because the pain of these losses has not been acknowledged or validated, taking the time to grieve for ourselves is important. Left unexamined and without appropriate avenues for expression, these feelings of loss grow into emotional time bombs that can become extremely hurtful. We act them out in depression, addictions, compulsive behaviors, hurtful relationships, difficulties with parenting, and so on. It is common to hear people say, “I feel as if something is missing.” That something missing is often what we needed, but didn’t get.

The classic grief model encompasses a series of universal emotional reactions. The model always begins with loss and from that loss comes shock. We are numb to what has occurred; we disbelieve. From shock we move to denial. We minimize, rationalize; our loss is too painful to acknowledge. In order to get to acceptance, people move through anger. Guilt is experienced, which leads to bargaining. This bargaining is often between ourselves and our God or Higher Power. Sorrow is experienced. We feel too helpless to respond. Ultimately, we come to acceptance.

While adults from troubled families are not grieving death per se, but grieving chronic loss, they have their own added overlay to the classic model of grieving. When loss is chronic and there is a likelihood of abandonment at emotionally painful times, we would be more apt to bypass the shock stage of grief and quickly move into the denial stage. Often we become so skilled at this we have difficulty even identifying a situation to be a loss. “No, it wasn’t important to me that my father didn’t come home at night. He would have been drunk anyway.” “No, it didn’t bother me that my mom slapped me. I was used to it. It didn’t really hurt.”

Anger is a natural response to loss. It is a protest, which is an attempt to retrieve that which is gone. But, unfortunately, when people are frightened of rejection, distrusting of their own perceptions, and greatly dependent on others’ approval, they have difficulty owning their anger. They don’t want to be angry. They want to be understanding. As a result, many people find it easier to move to guilt or depression. Unfortunately, the inability to identify anger interferes with the ability to move through the grief process.

The natural depression that is a part of the grief process is where many people are apt to become stuck. When we face losses with an internal belief that we aren’t worthy, we are more apt to succumb to the power of depression and experience a more chronic state of depression.

Both true and false guilt is a natural response to a loss. True guilt is a feeling of regret or remorse over something we have done. False guilt is a feeling of regret or remorse for someone else’s behavior and actions. Because we have greater difficulty delineating true from false guilt, we are more apt to stay stuck. As a result, we continue to wonder what it was that we could have done to have made things different. “If I had only gone to sleep like I was supposed to. . .” or “If I had been a good enough kid. . . .” The false guilt we carry with us also keeps us stuck in the bargaining stage.

As painful as it is for anyone to wend their way through a grief process, many people find a type of psychological safety in their bargaining. To let go of the bargaining and to reach a healthy place of acceptance you have to allow yourself to acknowledge and tolerate the intensity of your feelings. Acceptance comes as a result of being able to experience each step of this grief process. When it isn’t safe to feel, we cannot get to that acceptance.

As you review the grief model, describe where you are more apt to get stuck in the process. What are the beliefs that keep you stuck? What self-care behavior can you practice while you are exploring your losses?

Now that you understand the grief process and where there is potential to become stuck in the process, you are armed to meet your past or present-day losses. It is necessary to continue with Step One of Exploring Past Losses:

1. Identify the losses (the wrongs, the hurts) that happened as a child. Not only is it important to grieve the wrongs and hurts, but it is of value to mourn the loss of what you didn’t have.

2. Allow yourself to feel your losses. It is important that you feel, in addition to identifying and understanding what happened.

3. Embrace and endure those feelings. We need to let them become as big as they really were back then. That is, we must feel the pain all the way through to the deepest levels so no more pain will be left.

4. Share those feelings with others. Sharing feelings is a way of bringing light and air to the wound, allowing it to heal. Shame subsides when a wound is no longer secret; it disappears in the light of another’s acceptance.

The process of grieving and attending to your losses will take weeks, often months; for some people it may take years. For most people, it is a process they periodically come back to as specific issues come up.

A Cognitive Life Raft and Emotional Safety Net

Before people are ready to feel the feelings associated with the past, they need to have an intellectual understanding of how past events have affected them. They need to have information about what is “normal”; that is, how their environments differed from “normal” environments that did not result in a restricted life of lasting pain. They need to hear others talk about experiences similar to their own. Reading about others’ similar experiences also helps so they will have a language to understand and talk about their own experiences.

Gaining these insights and understandings allows you to know you are not crazy. You are not bad. There are reasons for your feelings. This process provides a sense of safety and, as described by Lorie Dwinell and Jane Middleton-Moz in their book After the Tears, is known as the Cognitive Life Raft. This information will normalize the struggle.

You will also need an Emotional Safety Net. This occurs when you form a trusting relationship with the person(s) who will guide you through your process. In order to walk back through the pain, there must be a feeling of trust of self and the trust of at least one significant other with whom you will work through the process. While you need to own your fears, sadness, hurt, and anger, you don’t necessarily want to do that with your parents; however, you will want to do it with a counselor, other recovering adults, or a trusted friend.

We need to feel safe in order to trust and to share our vulnerabilities. That will take time. For some, it is easier to experience their grief than to develop an Emotional Safety Net. In our childhood, when we trusted someone vital to our emotional well-being, we were often betrayed. Consequently, our fear of trusting means that we will need time to struggle with our feelings when we begin to trust significant others again. It is this process that eventually leads us to the acceptance and validation of the children we once were.

Compared to the other three steps in the recovery process, the first step of exploring and grieving the past is the most emotionally painful part of recovery. At times recovering adults have been criticized for focusing on the past too much or for “staying in the problem,” as opposed to searching for a solution. However, at this point we are in the process of owning our childhood experiences (grieving losses) and we must take whatever time we need. Everything can’t be remembered at the same time, nor do feelings come to the surface all at once.

Fear of Feelings

Fear of feelings makes it difficult for most of us to talk about the past. Where there is loss, there will be tears. Where there is loss, there will be anger. We must be willing to show our feelings. Feelings don’t go away. Repressed feelings only serve to distract us from our real self. We must speak to the sadness, the angers, the fears that we never had an opportunity to own or express, and grieve for how we had to live our lives.

You probably have a lot of fear about what will happen if you show your feelings, most likely as a result of what happened when you were a child. If you showed your dad that you were angry, you were apt to get hit across the face or told that you didn’t have anything to be angry about. If you showed you were sad, nobody was there to comfort you, to validate that sadness. Maybe you were told to shut up or you were really going to get something to cry about. The people you loved didn’t acknowledge when you were embarrassed; in fact, they may have done things to embarrass you, even to humiliate and shame you. No, it was not safe to show your feelings when you were growing up and, as a result, not only do you avoid expressing your feelings now, but often you don’t really know what they are.

I’ve seen people sit with tears streaming down their faces, clenched fists pounding on the desk, and when asked, “What do you feel?” they respond, “I don’t know.” It’s very common to be so emotionally disconnected from yourself you have difficulty not just showing feelings but identifying them as well.

To help you explore your feelings, answer the following questions:

• What feelings are easiest for you to show people?

• What feelings are more difficult for you to show people?

• What do you fear would happen if you showed the difficult feelings?

So often the fear of what would happen if we showed our feelings is the echo of what we feared would happen when we were children. It is helpful to ascertain how realistic the fears are today. If they are realistic, what needs to occur for the fears to no longer be valid?

Sadness

If we become sad, we fear that no one will be there to comfort us; people will walk away from us or take advantage of us. They will see us as weak or vulnerable, and that is equated to being bad.

As I said earlier, where there is loss there will be sadness, and where there is sadness there will be tears. Many of us have not cried in a long time. Tears can be very frightening if you have not cried for five, ten, twenty, even thirty years. When that is true, sometimes we are afraid that if we start crying, we will never stop.

I want you to know that your fears about what will happen when you begin to cry are typically far greater than the reality. I have often repeated throughout my years of working with clients that nobody yet has had to be carted out of my office because he or she has cried too hard. You may cry for what seems like eternity, but it will only be minutes. The heavy tears last usually three or four minutes, maybe nine or ten. This may make you feel awkward, embarrassed, or afraid, because crying may be a strange experience for you, but nothing bad has to happen. You won’t die. You won’t go crazy.

When people feel emotionally vulnerable and don’t want to be with their feelings, their breathing often becomes very shallow. Soon they are breathing from the chest up or, it seems, from the neck up rather than from the gut. Then they get a pain in the back of the ears and feel like they are breathing from the ears out. If this happens to you, it’s very important to take slow, deep breaths. Check your breathing. Breathe deeply.

When you cry, you may get flushed in the face. Tears may run down and drip off your nose. That’s what happens when people cry. But you are going to feel a sense of relief. You won’t have as strong a need to be in control and that will feel good. When the crying is over, you will find you are not carrying so much of the burden of the world on your shoulders any longer.

Anger

In addition to being afraid of sadness and tears, people often fear their anger. Typically, adults with unresolved pain also have a lot of unresolved anger. Some are very much aware of it. Others are so removed from their anger, they are mystified by the thought. People’s fears of what would happen should they express anger are, as with sadness, usually far greater than the reality of what would occur.

When people become angry, their voices may raise, their faces may get flushed, and their bodies tighten. Fear and sadness may accompany the anger. Angry people who don’t express their anger often find it eventually gets expressed directly in unpredicted outbursts, or indirectly in twisted and distorted ways, such as in overeating, insomnia, sarcasm, illness, or violence.

Adults who have kept their anger stored away are often afraid they’ll become angry people. It’s not a matter of becoming. It’s a matter of owning. The fear I have heard expressed the most is that these people are afraid they are “going to blow somebody away” with their anger. Most adults don’t mean that in the literal sense. When I’ve asked clients to tell me what that looks like when they “blow someone away,” I discover that it most often equates to raising their voices at somebody. Yet they have this perception that they have the power to blow someone away.

This perception comes from their childhood. When parents got angry, many children felt as if they were going to be blown away. They felt backed up against a wall and helpless. They may have felt as if their whole life was crumbling because of someone else’s response. When someone raised a voice or acted irrationally, the child wanted to disappear. When parents yelled, they didn’t talk about behavior, they talked about you, your person, your being. They attacked your whole essence. Of course you felt “blown away,” especially if this took place when you were developing your sense of worth and identity.

Today, if you disagree with someone, if you need to say no to someone, and if you raise your voice in anger, you have that sense that you are hurting them in that same fashion as you were hurt as a child. That needs to be put into perspective. At times, you will raise your voice. You will need to say no. You will need to disagree. You can learn to express anger regarding another’s behavior without ever attacking another person’s identity, value, or essence. You do not have to do to another what was once done to you.

Often there is accumulated anger. Therefore, the anger you may feel at the moment should not be combined with all of the anger you have stored up and then heaped on the immediate source of your anger. It is often helpful to express that anger elsewhere first and then decide whether or not it needs to be directed toward the source. Remember, as you discover your feelings it is not necessary for you to be alone to figure out how and when to express them. Those who are part of your recovery process can often offer direction. Here are some questions to help you discover your feelings of anger and sadness:

• What picture comes to mind for you when you visualize yourself showing sadness? Showing anger?

• What old messages were you given about those feelings?

• Are those messages hurting you today? How?

• What new messages can you now create for yourself?

If you were raised in a home where people physically hurt other people, or if in your own adult history you have been physically abusive to yourself or others, the fears concerning your anger are naturally greater and have more basis in reality. To make the process of expressing your anger safer and more meaningful for you, the assistance of a professional counselor who can facilitate your anger work is strongly recommended.

Guilt

It is possible that the fear of exploring the past is not about what will happen if you get in touch with sadness or fear, it is about verifying the guilt you feel over your growing up years. You still believe there must have been some way you should have been able to influence what happened.

As a child, you could not have known then what you know now. Nor could you have changed what occurred. You must stop trying to take on the responsibility of your growing up years. You were a child and your experiences were influenced and shaped by others. That is the consequence of childhood.

Some of us find it so hard to believe we really couldn’t control what happened in our families! Yet, while we could not control our childhood, we can influence how it impacts who we are today.

Feeling guilty for other people’s behaviors and actions is a “false” guilt. Taking on guilt for things over which we had no control is false guilt. There are enough things in life for which we are responsible and therefore can experience “true” guilt. Believing we were responsible for parental behavior, addictions, compulsions, or believing we should have had the insight or skills of an adult when we were a child or teenager is not among them.

Overcoming the Fear of Feelings

Remember, recovery takes time. You don’t have to do it all today. When you begin to tell people of your awkwardness or your fears, they won’t seem so overwhelming. Feelings are only hurtful when they are denied, minimized, and when they accumulate.

Know that in the early stages of healing, your feelings will arise from many sources and some may seem very contrary to each other. You may feel sad and happy at the same time, or sad and angry, or loving and hateful. It is possible for all of us to have many contradictory feelings at the same time. You have not gone crazy. It only means you’re sad and happy, sad and angry, or that you love and you hate.

Also, trust that there are reasons for the depth of your feelings. Whatever you feel doesn’t mean you are bad. What’s important is that you are able to talk about those feelings and that you begin to put them out in front of somebody else. You don’t have to know the sources of your feelings. But you can open your mouth and say, “I’m sad. I don’t know what’s going on, but I feel sad.” The more you verbalize what you do know and what you feel, the sooner you’ll be able to connect your feelings to the sources.

The goal in this process is to be able to discover and acknowledge the reality of what has been lost, to feel the feelings associated with the loss(es). To do this requires support and a willingness to relinquish the emotional maneuvers that you have used to deny this reality. You need to be able to admit that the loss is permanent. You will never experience the ideal that you so desperately wished for in childhood. While you can do much today to get many of those needs met, no amount of experience or grieving will completely erase how it was “then.” Ultimately, this allows you to be willing to withdraw your emotional investment in what has been lost and move on in your recovery process.

It is usually early in the discovery process that the pain may seem overwhelming, but it will pass if you are willing to identify and own it. It is very important that you have a support system, people you can talk with regularly about these feelings. Talking, rather than keeping the feelings within, often takes the power out of the feelings. Receiving validation from others lessens the pain as well.

As you begin to experience these pent-up feelings from the past, go ahead and fully feel those feelings. As intense as the pain can be, trying to control and defend those feelings prolongs the pain. Allow yourself the feelings. Own them and be with them. Remember that a lot of what you are experiencing is the accumulation of many years of feelings—feelings that previously were not safe to experience. This does take time, but people who actively pursue self-discovery in a therapy or self-help environment find that usually within six to eight months the pain has greatly lessened.

In those times of great feeling, you may need to take deliberate steps to lessen external stresses. This is no time to take on added responsibilities. Make more time for yourself. Stay aware that this is a vulnerable time—it is a passage that does not last forever. Now is the time to treat yourself with kindness.

Exploring your past and grieving the pain associated with your losses is vital to recovery, but it is just as important to move beyond this first step. If not, you will become stuck in the process and it will then become a blaming process, not a grief process.

Talking about your childhood is not the complete answer to changing the course of your life. This is a time of much insight, awareness, and understanding of ourselves and others. It is a time of hope, a time of realizing that we have greater choices available. Hopefully, the talking and new awareness will bring us to our turning point. But once we reach that point, we must take three other steps that are vital for our recovery.

Step Two: Connect the Past to Present Life

“How Does This Past Loss Influence Who I Am Today?”

Connecting your past to the present is more of a rational, insight-oriented process than an emotional process. The cause-and-effect connections you discover between your past losses and present life will give you a sense of direction. It allows you to become more centered in the here and the now. This clarity will identify the areas you need to work on—where pain still affects you, where you are missing the skills needed to get free of the influences and restrictions from the past.

As you work on answering the question “How does my past affect who I am today?” you become increasingly centered in the here and now. Also, you will need to address that question to various areas of your life, such as:

• How does my past affect who I am as a parent?

• How does that affect who I am in the workplace?

• How does that affect who I am in a relationship?

• How does that affect how I feel about myself?

These are questions we seldom take time to ask ourselves, but the answers are vital in our recovery. It is helpful to take the time to write your responses. Growing up with shame, you had a tendency to intellectualize most things. Through writing you may find yourself more vulnerable and, as a result, more honest. And as you work on this step in your recovery, you need to make each question even more detailed. Here are some suggested, more specific questions for the general areas of self, relationships, parenting, and your work environment:

1. How does the fact that I lived with chronic loneliness for the first twenty years of my life affect how I feel about myself today?

2. How does that affect me in the context of my relationships? friendships? in my parenting skills?

3. How does the fact that I was so fearful of making mistakes in my childhood affect me today in my work? in my play? as a parent?

4. How does the fact that, as a child, I was always seeking approval affect me today in my parenting? in my relationships? at work?

5. How does the fact that I spent so much of my childhood in isolation and a fantasy world as a child affect me today? in my expectations of myself? my choice of friends?

6. How does the fact that the only way I could find safety was to create a fantasy world affect me in my choice of careers?

7. How does the fact that I lived with chronic fear affect me today in these areas of my life?

8. How does the fact that it was never safe to express my anger affect me in these areas?

9. How does the fact that I lived with a mother who was emotionally cold, a father who was never satisfied with what I did, affect me today?

These are the kinds of questions we need to ask ourselves and the kinds of questions that create a cause-and-effect connection between our childhood years and our lives today.

We often make assumptions about one of the areas of our lives without going through the exploration process. For example, we may assume that since “work is good,” and “I am doing a good job,” we don’t need to explore that area. But, by asking ourselves these questions in Step Two, by linking the past to how we function in the present, often we discover ways that we continue to perpetuate pain or repeat old behaviors that hinder rather than help us. By asking “How does the fact that I used school and keeping busy to detract from my loneliness relate to my work today?” we may find that we are presently using work as the detractor that school once was. We may work sixteen hours every day for weeks and then reward ourselves by going on a food or alcohol binge, or a spending binge, seemingly to reward ourselves for a job well done. Very likely we did do a good job at work, but what we have done even better is add to our load of shame—another ten pounds gained, another drunk-driving ticket, another outrageous credit card debt and a closet full of clothes we don’t need or really want.

While this step connecting the past and present offers us insight, it also will bring up feelings. For instance, think about what it means to be forty-five years old today and still afraid to make a decision. How does that make you feel about your adequacy? Further, what if you haven’t learned to listen? How has that interfered in relationships with intimate partners? What do you feel when you try to identify your needs? The answers to such questions bring up a lot of pain.

Sherry, a client, reflected, “It was so hard to be with my pain because I realized the fantasy life I created for myself as a child has been what has kept me so unrealistic in terms of my life goals. I realized it never felt safe to make a decision, and that is still true today!” We are often grateful to understand the past-present connection and find it useful to be able to recognize how old messages and experiences still dictate our lives. Yet, we also need to own the anger we may have about that, or the sadness that accompanies the insight, or even the fear that comes with now wanting to change certain patterns.

We need to connect the past to the present. And, as we do that, we need to feel the feelings, identify the source of the feelings, and grieve the pain.

Step Three: Challenge Internalized Beliefs

“What Are the Beliefs I Internalized from My Growing Up Years?”

“Are Those Beliefs Helpful or Hurtful to Me Today?”

“What Beliefs Do I Want to Have Today?”

Beliefs we internalized in our growing up years often continue to determine our behaviors without our being aware. These messages were often parental attitudes and value statements that became “shoulds.” First, we need to identify the beliefs and then we need to ask ourselves whether these messages are positive or negative, helpful or hurtful, to how we want to live our life today. We need to question whether or not these internalized messages are messages that we want to continue to take with us throughout our adulthood.

So, we begin this step asking, “What do I believe about _______?” and then we must challenge our answers: “Is that a belief that is helpful to me today?” or “Is that a belief that is harmful to me now?”

Examples of beliefs we often learned at a young age that are hurtful to us are:

I can’t trust anybody.

Nobody is ever going to be there for me.

I am not important.

I am not of value.

I better do things right because if I don’t, something bad is going to happen.

My needs are not important. Everyone else’s are far more important.

There’s no time to play. I have to get things done.

I am supposed to take care of others.

I can’t do anything, so don’t bother.

Whatever I do, it’s never good enough.

Other _____________________________________

Return to the list and put a check by the beliefs from which you operate. Name additional beliefs that were formed from your experience that are hurtful now.

These hurtful, internalized messages interfere with skill-building. For example, if you truly believe your needs aren’t important, it will be difficult to learn to express your needs. If you believe you can’t do anything, or what you do is never good enough, you won’t initiate or try anything new on your own. If you believe your job is to take care of others, you will very likely neglect yourself. It’s going to be important to identify a certain message and to decide—to choose—whether or not this is a message you want to keep.

Once hurtful messages are identified, you need to symbolically let them go. Many adults changing course skip over this part of the step. They explore the past, they connect the past to the present, they try to learn some skills, but they don’t actively look at the messages they have internalized. And sometimes when they do look at a message and identify it, they don’t actively get rid of it.

There are many ways to symbolically get rid of an old belief.

Write the message down and tear it up. Write it down on a piece of poster paper, put it in a chair, and say “No” to it. Do a visualization of the belief; that is, visualize the belief and watch it disintegrate. If you play computer games, put the piece of paper with the message on it into a playing field and bomb it. Another way to get rid of a belief symbolically is to do some type of ritual exercise to let go of it. Develop a ritual that works for you. It is important for you to get actively involved in letting the message go. The purpose is serious, but the process here can be fun.

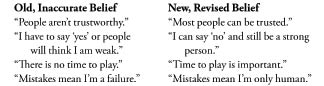

After the ritual of letting go of the old belief, replace it with a healthy message. Here are some examples of old, unchallenged beliefs replaced with beliefs you choose.

Although you need to replace negative beliefs, you probably received some helpful messages from your family. It will be just as important to ascertain what those were. You may have heard from your father that you were special, of value. Or that you could do whatever it is that you wanted to do (high expectations). You may have heard the Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you want them to do unto you.” Many times these are messages that you would like to continue to take with you in life. When that is true, you need to take ownership of the beliefs.

You need to know what you believe, not just your father’s (or mother’s) belief system that you have internalized. You need to literally say, “That’s what my father told me and that’s been very helpful to me. Now I believe that for myself.” You don’t need to hear them just as your father’s message for you. You will take ownership of the message, the belief. “I am capable, I am special, I am of value, and I can do whatever I set my mind to doing.” The baton has been turned over to you, so to speak, and you are now responsible for carrying this message.

Once you have discovered any “parental beliefs” or “shoulds” you have internalized that are getting in the way of how you want to live your life, toss them out. But again, know that while this begins as more of an intellectual search, you will have feelings that need to be felt. Identifying that you have lived a life believing “My needs aren’t important” is something to be angry about. Recognizing that you have experienced “No one wants to listen to what I have to say” is very sad. As you reframe a healthier message in the place of the old message, you must work through the emotions of change.

Be thorough as you work on this step, because it is the one people are most likely to skip over and neglect. It can appear insignificant or trivial. In general, a strong emotional reaction is not created, so there is not the level of excitement some people expect in recovery. Depending on which issue you are addressing, it can be very “emotionally loaded,” but that is not the main idea of this step. The point is that it is vital to address your issues and take more responsibility for how you live your life today.

It is in working on these three steps that you are ready to truly learn and incorporate new behaviors or skills into your life.

Step Four: Learn New Skills

“What Do I Want to Do Differently Today?”

Ultimately, our life changes when we learn skills or behaviors—things we can learn to do to take care of ourselves and to have healthy relationships with others—that we didn’t learn in our earlier years. “I want to be a better listener,” “I want to learn to solve problems better,” “I want to be able to see options,” “I want to learn to negotiate better.” These are living skills and “people skills,” ways of being with your self and with others.

People will often want to bypass the first three steps and simply get on with learning new skills. Most of us are in a hurry to move on in our lives and that is understandable. Ever since childhood, we have been anxious to leave the present moment in anticipation of the next day. We were certain the next day had to be better. We don’t want to grieve, or to take time to be insightful about connecting the past to the present, or to spend time doing what appears to be a trivial exercise of challenging our beliefs. We have other things to do. But we must be willing to prioritize our recovery. That means taking the time to walk through each step of the process.

You can immerse yourself in programs that focus solely on behavioral change. However, most people find that if they do not do each step in successive order, they won’t follow through with practicing the new skill because they have not addressed the emotional component to each skill.

Let’s say, for example, that you want to do a better job of setting limits for yourself. You want to be more assertive because you are feeling victimized in certain situations. But what happens is this: You can learn assertiveness techniques and skills, but very likely you won’t follow through and actually use those skills because you haven’t dealt with the issues of the fear of rejection and the need for approval. Those are the emotional issues connected to the skill.

Or you want to learn how to ask others for help. You can identify safe people, develop a behavioral hierarchy identifying a list of items or issues to ask for help with, but unless you deal with how frightening it was to ask for help as a child, you won’t follow through with practicing the new skill.

Your intellect or rational mind will now know what to do to bring about the result you want, but your underlying emotions will impede you actually choosing to act in that new way. The new behavior won’t follow until the emotional component underlying the old behavior has been dealt with. That’s what happens in the first three steps—you deal with those old beliefs and fears. You then create a new belief system that supports the new behavior, the new skill you want to learn.

As we change course, we go through a process where ultimately we withdraw our emotional investment in what has been lost and take responsibility for taking care of and respecting ourselves. This self-care and self-respect is created by developing and reframing beliefs that are supportive of our emotional and physical health, and then by learning the skills that act on these new beliefs, taking personal responsibility for getting our needs met.

Learning Adult Skills as a Child

Children in troubled families do learn skills. In fact, sometimes they learn skills that other children don’t. Some learn to cook at a particularly young age. Others become very skilled at controlling their emotions. In their hyper-vigilance many develop strong listening skills. They also become creative in their problem-solving and very self-reliant.

Often we were responding to situations as if we had the skills of an adult, but we were still children. Unfortunately, the skills we learned in a troubled home were often skills and behaviors that were premature for our age, or learned from a basis of fear or shame. When that occurs, there is a tendency to feel like an imposter. Also, because we developed skills from a premise of fear or shame and because we learned due to an immediate need, we were often limited in options and problem solving. This commonly translates to being very rigid in how we handle situations as adults.

So now, while we have skills, we don’t have flexibility. We have a sense of urgency about what we’re doing: “I had better do this, and I’d better do it right. I can’t make a mistake, because if I do, something bad is going to happen.” We are skilled, but we feel a sense of urgency with fear and shame close behind.

It is important to take a look at the skills you did learn. Be open to developing those even more fully with the input of healthier role models to whom you have access today.

To help you begin to look at your own experience, here are some of the behaviors or skills children need to learn.

• asking for help

• expressing feelings appropriately

• setting limits

• saying no

• validating yourself

• initiating

• asking questions

• negotiating

• problem-solving

• taking charge

• listening

• playing

List the skills you developed growing up. Then list the skills that you did not develop. Usually these skills are very basic, but are vital today in being able to address more complex skills in adult life.

Adult skills are often taken for granted, except by those who may not have had the opportunity to develop them. If we did not learn these skills as a child and adolescent, we move into adulthood forced to experience ourselves as if we were an imposter. We try to hide our performance anxiety, fear of change, and fear of problem-solving, spending a great amount of time and energy manipulating our environment so we don’t have to be confronted with what we perceive to be our “insufficiency.” But, often we didn’t know or didn’t understand there was another way to be.

Recovery offers you the opportunity to acknowledge what you need to learn.

>> To say, “I did not learn this very basic skill and I need to know how” is a turning point.

Feelings Associated with Learning New Skills

Learning new skills is much more behavioral than emotional, yet like the other steps there will be associated feelings. You will experience feelings as you identify and recover from the ways you have been trying to control your pain from the past. Also, you will have other feelings, such as awkwardness and unfamiliarity as you try your new skills and as you relate to other people in your newly discovered ways.

To be an adult and having to go back to learn basic skills at this point in your life brings up a lot of different, painful emotions. Each and every possible time you have a feeling, you must stop, pay attention to it—honor it. You need to

1. feel the feeling,

2. identify the source of the feeling, and

3. express it in the here and now. You will need to go through this process consciously until doing so becomes habit, until you consistently meet your own needs.

Here are some pertinent questions to think about to help bring your feelings to the surface:

• If, as an adult, you are in the process of learning to make decisions, how does it make you feel having to learn that skill now? afraid? angry? sad?

• If you are just now learning to listen to your significant others—family, friends, and intimate partner—how do you feel about the problems that were created by your inability to be open to hearing them? sad? guilty? regretful?

• When you try now to identify your own needs, how does that make you feel? confused? insecure? uncertain? afraid?

• Not knowing your own needs surely means these needs weren’t being met. As a result, your neediness may affect your present-day relationships. What feelings do you have about now trying to have your needs met in your relationships? fear? confusion? insecurity?

Each of the feelings you name as you answer these questions includes a lot of pain. When you begin to practice the skills that allow you to take care of yourself, you often feel as vulnerable as a child who is just learning to read. You are no longer that child and so you do not want to tell yourself you “should” be able to do these things. Remember, this is not about “shoulds.” Maybe it was not safe when you were growing up to have learned a certain skill, such as assertiveness. Or perhaps there were no models of this skill to learn from. Whatever your circumstances, you coped and survived as best as you could and it was not until later in life that you could recognize that you lacked these kinds of skills.

Applying the Four Steps to a Recovery Issue

Each and every issue in your recovery process will usually be addressed by these four steps. Let’s use as an example that saying no is a problem for you now because of what you experienced around the word no as a child. Here’s what your process might look like.

Step One: Explore past losses.

How did you hear no as a child?

Who did you hear it from?

What did that experience mean to you as a reflection of your worth? Of your parents’ care for you?

What happened when you said no as a child?

How did that make you feel?

Step Two: Connect the past to the present.

How does your past experience affect you in the different areas of your life today?

When do you have difficulty saying no?

How do you feel when you say no?

Step Three: Challenge internalized beliefs.

What were the messages you got around no?

Take ownership of the helpful beliefs.

Cast out the hurtful messages.

Create new, constructive beliefs around the word no.

Step Four: Learn new skills.

Identify situations when you would like to say no.

Rank these from easiest to most difficult.

Practice the experience of saying no, beginning with the easiest and build up to most difficult.

In the example above, the four steps were applied to the problem of saying no. Here is another example of using the four steps, applied to difficulty in initiating:

Step One: Explore past losses.

What happened if you tried to initiate as a child?

What did you fear would happen?

Step Two: Connect the past to the present.

How does not initiating today impact you in different areas of your life?

What could you have in your life today if you did initiate?

Step Three: Challenge internalized beliefs.

As a child, what messages did you get about initiating?

Cast out the hurtful messages.

Create new beliefs that support you taking initiative versus being passive.

Step Four: Learn new skills.

Identify areas in which you would like to take more initiative.

List identified skills in a hierarchy, beginning with those that are the easiest (or safest) to those that are the most difficult or scariest.

Now begin with the safest, building up confidence to be able to respond to the most difficult.

Recovery Can’t Be Rushed

Be kind to yourself. Give yourself credit. Remember that as you work the recovery process, you are working through the four steps to a greater freedom.

>> Recovery isn’t changing who you are. It is letting go of who you are not.