CHAPTER 1

The Background

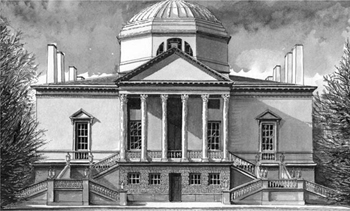

FIG 1.1: CHISWICK HOUSE, LONDON: One of the first great Palladian mansions, built in the 1720s by the 3rd Earl of Burlington, who promoted the architecture of Palladio and Inigo Jones, both influencing the design of 18th century houses. Palladio was arguably the first professional architect, working in 16th century Italy and publishing his theories and designs for later generations to interpret. Inigo Jones brought this classical style to these shores in the early 17th century and created buildings way ahead of his time, ones that were not appreciated and imitated until brought back to life by Burlington and his disciples.

A Brief History of the Georgian Period

Two principal themes from popular culture and school history textbooks tend to dominate most views of the Georgian period. On one side there is the image of the classical country house set in vast, sweeping parkland, with sensitive gentlemen being whisked away in carriages to formal city squares where walking and dining seemed the main preoccupations. It is a world of elegance, indulgence and wealth dominated by aristocratic families, shaped by Robert Adam and Capability Brown and recorded by Gainsborough.

On the other side there are the Industrial and Agricultural Revolutions, with new townscapes of fiery furnaces, smoking chimneys and back to back housing contrasting with a countryside divided up into regular units, the preserve of the wealthier local families. It is the time of the inventor and entrepreneur, Watt, Trevithick, Wedgwood and Boulton, and of rural revolution in the form of enclosure and emparkment, the move from husbandry to farming for a profit.

The commonly perceived images listed above, however, are only part of the picture, and one which either changed little or slowly at best, and was far from complete by the end of this period. Although this Age of Reason where the medieval and modern worlds met was shaped by a drive for improvement, commercial expansion and the threat of revolution, a powerful aristocracy and ancient institutions still held a tight grip on the reins. Despite the gradual sapping of power to Parliament, the monarchy still sat at the top of the pile, selecting ministers and directing policy, and the succession of each was still a cause for concern, no more so than when Queen Anne, the last of the House of Stuart, died in 1714.

THE HOUSE OF HANOVER

How did the Elector of Hanover (one of the series of small German states, which did not form themselves into the modern-day country until 1870) find himself the king of England in 1714 and the first of the four Georges from which the period is named? The answer lies with the previous Stuart kings who had Catholic sympathies that were wisely kept under wraps in a country in mortal fear of a return to the old faith they had so painfully broken away from in the 16th century. However, when James II came to the throne in 1685 the problem returned to the fore. This arrogant, ill-advised king made no secret of his Roman Catholic conversion and attempted to position men of similar faith in high office. With the birth of his son in 1688 it became clear that a Catholic dynasty threatened and a group, including the Bishop of London, invited William of Orange, the son of one of James’s sisters and the husband of James’s daughter Mary, to take the throne. His subsequent landing with, in effect, a Dutch invasion force resulted in James, who had lost the support of Parliament and the armed forces, to turn and run, surrendering his throne but not abdicating.

To ensure a Protestant succession the Act of Settlement was passed in 1701, which required any future monarch to be a member of the Church of England. This was a position which Anne, the second daughter of James II, embraced wholeheartedly when she ascended the throne on the death of the childless William in 1702. Her tragedy was that her seventeen children all died in infancy except William who lived to only eleven, so upon her death in 1714 it was feared that the succession would be threatened by the son of James II, the arguably rightful heir to the throne known as the Old Pretender. The 1701 Act had to go back to the children of James I to find a Protestant succession, with the crown being passed on to the grandson of his daughter Elizabeth, who had married a German prince. With the Jacobites (the followers of James Stuart, from Jacob, the Latin for his name) disorganised, the new Hanoverian King George took the throne with little opposition, the expected threat from the Old Pretender being defeated in the following year.

George I could barely speak a word of English, preferred to spend his time in his beloved homeland and was surrounded by controversy over the imprisonment of his wife and the suspicious death of her lover, especially when his bones turned up under the floor of one of the king’s palaces! His most notable act was leaving the country in the hands of Robert Walpole, whose dominant political position made him in effect our first Prime Minister, and ushered in a period of relative political stability after the turmoil of the previous century.

The king’s son, George II, who succeeded him in 1727, was still influenced by his German upbringing and, as with many of his predecessors, was happy to share the court with his wife and a series of mistresses. His other passion was warfare and at the age of 60 he became the last English monarch to fight on the front line, in this case against the old enemy France. The main threat of his reign, however, came from the Young Pretender, Bonnie Prince Charlie, who led a Jacobite invasion in 1745 to reclaim the throne, reaching as far south as Derby before returning to Scotland. He was defeated by George’s brother, the Duke of Cumberland, at Culloden in the following year, which in effect ended the Catholic threat to the throne.

FIG 1.2: PICKFORD’S HOUSE, FRIAR GATE, DERBY: This house, dating from around 1770, was built by Joseph Pickford on the road along which, only 25 years earlier, Bonnie Prince Charlie had ridden into Derby during the rebellion of 1745. This was the furthest south he reached before turning back and being defeated in the following year at Culloden. Today the house is an excellent museum with a totally restored interior and garden.

The succession skipped a generation to George II’s grandson in 1760, a young man who having been brought up on this isle could claim to be English. Much has been made of George III’s bouts of madness but the insanity was probably misdiagnosed and exaggerated, in part by his son, the future Prince Regent, who like the other Hanoverian kings was a thorn in the side of his father. Despite this, Farmer George, as this enthusiastic agricultural improver was affectionately known, was popular and a devoted family man, setting new moral standards for the monarchy, which came under increased scrutiny in the wake of the French Revolution which began in 1789.

FIG 1.3: PARK CRESCENT, LONDON: Part of the Regents Street and Park development built by John Nash for the Prince Regent, later George IV.

His son, the Prince Regent from 1811 until his father’s death in 1820 and George IV for the following ten years, had no such reputation and despite being a society man and connoisseur of the arts was mocked as overweight, vain, dishonourable and a liar. His passing away in 1830 raised barely a murmur from the public and the period named after his tenure, the Regency, and its distinctive and colourful architecture credits him with a place in history that his character little deserved. His ill equipped successor, Silly Billy as he was known to the family, never expected to be king and yet in his short seven year reign William IV restored dignity to the throne and played a vital part in the passing through Parliament of the Reform Act of 1832.

POLITICS AND WAR

Reform of Parliament was well overdue by this time as the electoral system was still medieval with patterns of representation that protected aristocratic rule but hardly matched the new urban populations that had developed through the Georgian period. Despite this lack of change there were many aspects that had improved as it grew in influence and power throughout the 18th century. Rather than being called upon only when the monarch required funds, Parliament now sat at a regular time each year, the arrival in London of the MPs and their entourage (generally in autumn) signalling the start of the ‘Season’. This lasted through to the following spring, a social whirlwind that in turn affected the development of the capital. Stability had also been achieved with a seven year length of government rather than the previous three year term. Other important changes were the appearance of salaried civil servants who were awarded positions on merit rather than by connections, and the development of long-term planning, commissions and white papers, with political parties formed around policies rather than patronage.

The Georgian kings and their governments generally believed in a non-interference policy, removing restrictions for economic expansion and giving a free rein to companies, private individuals and financial institutions. However, they operated by different rules when it came to warfare! Spurred on by trading interests and a dislike, especially, of the French, Britain became interwoven in European politics and fought what were openly termed as ‘commercial wars’ with the reward of territorial gains and the resulting increase in trade the carrot dangling at the end of the stick. The country was generally successful in this policy, finding itself by the end of the period with a massive empire bound together by trade and protected by the Royal Navy, which ensured supplies of raw materials and foods and a ready market for its manufactured goods in return.

However, the loss of the colonies in 1783 after defeat in the American War of Independence and the threat of invasion from France during 1793 to 1815 caused disruption in the economy and society back home, with those on the bottom rung of the ladder usually suffering worst. The after effects of this latter conflict posed the greatest threat to the authorities, with post war economic depression, hundreds of thousands of disbanded soldiers looking for work, poor harvests, protest rallies and the threat of revolution. The Reform Act of 1832 was in part a reaction to quell this by granting the vote to a wider proportion of the middle classes, although any ideas of democracy and working class representation were far from their thoughts.

AGRICULTURE, INDUSTRY AND TRANSPORT

Despite increased trade and commercial growth, agriculture remained the dominant industry and cornerstone of the economy throughout most of this period. The wealthy relied upon rents from tenants on their estates and they in turn upon a healthy market for their produce, which increasingly went for sale rather than sustenance. The variable demand, warfare and the weather created a fluctuating picture but after poor years in the 1730s and 40s agriculture generally picked up, especially in areas where new enclosures had reorganised the fields into more efficient units.

Industry at this stage was widespread but generally small in scale and even where large works or mills were constructed much of the manufacturing process was carried out by families at home in the surrounding town and villages. As with agriculture, the drive for improvement was a defining character of the age. Financially supported by wealthy family members or others from the same religious group, inventors and entrepreneurs from even modest backgrounds could now design, conduct experiments and market their products on a larger scale.

There were two key factors in the growth of industry, the first being the steam engine. A restriction upon the early industrial workings of the 16th and 17th centuries was power which, as it principally came from waterwheels, limited the location and was susceptible to seasonal fluctuations in supply. The development of an efficient steam engine by Thomas Newcomen and its further improvement by James Watt gave a more flexible and reliable source of power and crucially carried out the pumping of water from mines so that the raw materials of industry could be extracted from deeper workings. The second factor was the improvement of the river navigations and development of a canal network, which reached a peak of construction in the 1790s. Transporting raw materials to site and the finished product away had restricted industrial growth as roads were too poor for heavy goods to be moved any distance and rivers were affected by droughts, flooding and obstructions, principally from mills. The canals were engineered to solve many of these seasonal problems and to reach areas not served by rivers, with the effect that the price of goods was reduced and new factories and settlements sprang up along their banks.

FIG 1.4: MASSON MILLS, CROMFORD, DERBYSHIRE: The second mill built by Richard Arkwright at Cromford, dating from 1783. Although the cotton was spun in this water-powered mill, other processes were carried out in houses, many built by Arkwright, in the neighbouring village (see Fig 2.15).

Passenger travel witnessed equally dramatic improvements. The thought of going from one part of the country to another in previous centuries either was not required by a generally insular population or dreaded by the few that had to. The journey was rough, unreliable and fraught with danger, most famously from highwaymen, and services that might run only once a week from London to the provinces could take days to reach their destination rather than the hours they would take today. Improved communication was another key element in the growth of industry and spread of ideas and it came with the breeding of stronger and fitter horses, more organised and regular services and the creation of turnpike trusts. Since Tudor times local parishes had been responsible for the generally poor maintenance of roads, but from the early 18th century turnpike trusts (named after the rising gate or ‘turn pike’ where tolls had to be paid) took over lengths of roads with the intention of improving the surface for a fee. This was done to such an extent that by the second half of the century more than 15,000 miles had been taken over. However, the standard did not always improve and the tolls charged were resented, especially as the rich got away without paying, so that the hated gates and their keepers were often targets for rioters.

FIG 1.5: Mileposts were erected by turnpike trusts along the length of road for which they were responsible.

FIG 1.6: CROMFORD WHARF, DERBYSHIRE: The terminus of the Cromford Canal, built for a consortium including Richard Arkwright whose earlier mill stands opposite, and opened in 1793 at the height of Canal Mania.

Georgian Society

After years of stagnation the population of the country began to grow in the second half of the 18th century, for reasons that are still not clear, although access to better food and housing – and soap – may have all played their part. Outbreaks of disease were still rife, particularly in the mid century, and the resilient population that emerged afterwards saw growth from around six million up to nine million by the turn of the 19th century. Much of this expansion came from London alone, which nearly tripled in numbers in this period to more than one and a half million by 1830. Other towns and cities were tiny in comparison but growth was even more dramatic in industrial centres and ports. For instance, Manchester, a modest town with under 10,000 people at the beginning of this period, had swelled to a potential city of 180,000 by the end of it.

Despite these growing concentrations of population, the majority still lived in the country and worked on the land, even in the midst of the Industrial Revolution. The social mix also only changed slowly in this period, with the bulk of the nation’s wealth in the hands of aristocratic and gentry families, which probably made up just a few percent of the population, and under-pinned by a growing yet still small middle class. More than three-quarters of the people in England were craftsmen, labourers, or vagrants with no representation, few rights, and a life potentially full of violent fluctuations in fortune. Surprisingly, though, rich and poor lived side by side in many areas, and it was common for a large house of a wealthy family in town to have narrow courts of working class dwellings at the rear, although the exodus to peace and privacy in the suburbs for those with money had already begun.

FIG 1.7: This magnificent room at Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire was designed by Robert Adam in the 1770s. It displays the aristocracy’s love for Ancient Greece and Rome, inspired by their Grand Tours and the work of Palladio, and turned into reality by leading architects of the day.

UPPER CLASSES

For the hereditary aristocratic families and the wealthiest gentlemen, the Georgian period was generally one where their incomes grew as land, the ownership of which was still the main status symbol in society, increased in value. This could happen due to suburban development, agricultural improvement or through the extraction of minerals and if it did not, as was often the case early on in the period, they could marry a rich heiress!

There were, however, an increasing number of delights and opportunities on which they could spend their money, and some still managed to get into debt. For many a young gentleman the climax of his education would have been the Grand Tour, a journey primarily to Italy to soak up the architectural and cultural wonders of the Classical Age and invariably buy up and cart half of it back with him! Second sons were increasingly attracted to the church, which, as the land attached to each living gained value, became a lucrative position. However, as they mixed in a different social circle they often became rather remote in their smart new vicarage from their parishioners, weakening the Church’s influence on their minds and souls.

The main expense for this class was building a country house. A need for increased space, often to store all the art work and sculpture shipped back from the Continent, and the demands of socialising were usually enough motivation. There was also the desire to impress guests with their refined taste for classical style but with the most modern of fittings behind the antique appearance. This resulted in large-scale rebuilding of thousands of country houses (most were refaced or extended; fewer were built completely from scratch due to the huge costs involved). The estate that it commanded came under the same scrutiny as landscapes were altered to mirror those of the classical world. They also provided a base for the new sports of foxhunting and shooting, in the process sweeping communities aside and breaking the traditional bond between manor house and manor.

Much of the year was spent in London or in the major provincial town or city where the aristocratic and gentry families would either own or rent a large house, attracted by business or parliamentary commitments and the social circle and leisure opportunities on offer. For those who could afford it there were assembly rooms for concerts, dances and gatherings, theatres for plays, and coffee and chocolate houses for meetings (which developed into Gentlemen’s Clubs later in the period). There were many other distractions, mistresses were common and illegitimate children numerous, gambling was the downfall of many a gentleman and drinking a serious problem (this is the time when the phrase ‘drunk as a lord’ was coined). It was not until later in the period that those in power developed a more dignified and sober image under the threat of revolution from below.

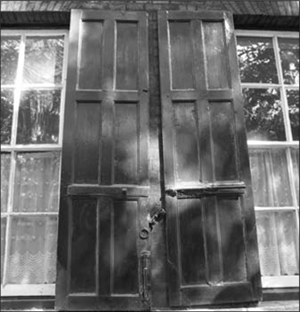

Crime and rioting were two other problems that faced the rich, especially as there was no police force, and both were accepted as part of life. Their houses were natural targets for burglars and rioters and they attempted to protect them with external shutters and elaborate door locks, which still survive on some properties today. Petty crime was rife in places and it was even known for wigs to be snatched off the heads of the unwary in the middle of the street! The only answer the authorities could come up with was to lower the offence by which you could be hung or transported – pickpocketing as little as 12 pence could send you to the gallows – although it appears that this action was no deterrent.

FIG 1.8: Shutters were commonly fitted to ground floor windows of upper and middle class houses, not only to protect delicate interiors from excessive sunlight but also, when the property was unoccupied, to deter thieves and rioters. The bolt was fastened from inside when they were shut, with a rotating stay (between the two shutters) holding them in place when open (see also Fig 4.34).

MIDDLE CLASSES

Below the wealthiest band of society were increasing numbers of professionals, businessmen, merchants, financiers, shopkeepers and farmers whose rising income permitted them to imitate their superiors’ lifestyle. In the first half of the period they tended to be subservient to the gentry but by the turn of the 19th century they began to form the distinctive characteristics we associate with middle class life, becoming critical of upper class behaviour, establishing groups promoting the Church and Sunday schools and campaigning against vice and slavery. Many of them began the 18th century working in ‘trades’ but by the end were described as ‘professionals’. One example were architects who were formerly gentlemen amateurs (Vanbrugh who designed Blenheim Palace began his career in the army) but by the early 19th century were trained experts with their own practices. The middle classes were, however, at this time still only a small proportion of the population with the largest concentration, probably around one in five, being in the capital. This expanding social group was one of the main driving forces for the building of the new terraced houses that will be the main subject of this book.

LOWER CLASSES

The vast majority of the population came under this broad banner, which could include a skilled craftsman in a brick-built cottage or terrace down to a casual labourer in a mud hovel, and below this an underclass of homeless vagrants. Compared with today, life in the town or city could mean unbearably long hours of work, irregular incomes, limited freedom and short life expectancy. Disease was rife, sanitation virtually non-existent, food was poor with most income going on bread, and wages often kept low in the belief that this would make workers more industrious.

This drudgery started at an early age, with many of the poorest or orphaned children put to work as young as five. Some of the worst conditions were inflicted upon chimney sweeps’ climbing boys who were starved to make them thin enough, although many still got stuck and if they did not die from this treatment they often developed cancer of the scrotum. In the country, things were little better and living conditions often worse, with daily life heavily affected by harvests, local disasters and changing weather. Those with the smallest holdings tended to lose out, especially if the village was subject to emparkment or parliamentary enclosure.

Compared with previous generations, however, the under classes at this time may have looked more favourably upon their lot. The increased wealth of the nation filtered down to this level with better wages or cheaper goods for some, although pay was irregular, varied dramatically between regions and trades and there was little security if employment dried up. Those coming into industrial centres from the country often found the rigid hours and regular wages of factory work a shock compared with the casual routine of agriculture, and many preferred to work fewer hours rather than labour for more money if times were good.

Most of the family would work, some in domestic service (the largest source of employment outside agriculture) or in mills, mines and factories or producing piecework at home. So, although many families would live in no more than a large single room, the whole family would only occupy it together for a short time each day. It was common for the man of the house to eat and drink out after work; the intake of beer increased and gin consumption boomed in the 1720s and 30s. Public houses were centres of the community, offering entertainment, bull baiting and cock fighting, and they were also places where business could be conducted. For those unable to work the poor law was provided but was only granted within the home parish, so many were reluctant to leave their town or village or had to return to it if work dried up elsewhere. This system, however, designed some two centuries before, could not cope with the new, rapidly expanding urban areas.

The lot of the working classes depended very much on where they lived, especially if this was in one of the urban or rural areas where change occurred. Before looking at the houses built, it is important to examine the new types of town, village and suburb where much of the new housing was erected.

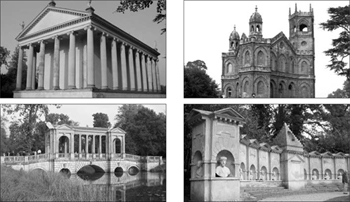

FIG 1.9: STOWE LANDSCAPE GARDENS, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE: The aristocracy sought to recreate classical views from Ancient Rome in their sweeping landscape gardens and built follies in a variety of styles as eye-catching pieces within the composition. However, in the process, many villages were re-sited or removed completely. Stowe is probably the best example open to the public of this effect. It not only displays outstanding monumental buildings but also retains its original medieval church, hidden behind trees from the original community.