1

A King’s Daughter

That princess rare, that like a rose doth flourish.

—James Maxwell, The Life and Death of Prince Henry, 1612

ELIZABETH STUART WAS BORN ON August 19, 1596, at Dunfermline Palace, her mother’s preferred summer residence, in Fife, just across the bay from Edinburgh. Her father was James VI, only offspring and heir of Mary, queen of Scots; her mother was Queen Anne, daughter of the king of Denmark. Elizabeth was her parents’ second child. An older brother, christened Frederick Henry but known simply as Henry, had been born two years earlier.

Unlike the wild, spontaneous public celebrations that had greeted her brother’s arrival—“moving them to great triumph… for bonfires were set, and dancing and playing seen in all parts, as if the people had been daft for mirth,” as one eyewitness noted—the news that Queen Anne, suspected of Catholic leanings, had been successfully delivered of a daughter was received with stony indifference by the unruly Protestant population. The Presbyterian ministers of nearby Edinburgh, the most outspoken and radical element of Scottish society, incensed by James’s recent decision to allow two formerly exiled Catholic earls to return to the realm, sent an emissary, not to congratulate the new father but to bait him, insultingly calling James “God’s silly vassal,” among other choice put-downs, to his face.

There were not too many kingdoms in Europe where a subject could address his sovereign lord in this fashion without risking imprisonment or execution, but fiercely implacable, wayward Scotland was one of them. The Scottish aristocracy was hopelessly, almost comically fractured by geography, ancestry, religion, and politics. Jealous of one another’s privileges, constantly engaging in conspiracies and treachery or jostling for advantage, about the only quality the various clans had in common was a tendency to take offense at the slightest provocation, a predilection that more often than not quickly escalated to violent civil unrest. To be king of Scotland at the turn of the seventeenth century was not an especially enviable employment. “Alas, it is a far more barbarous and stiff necked people that I rule over,” James observed morosely.

Exacerbating the country’s political woes was its extreme poverty. Trained almost from birth in the habits of frugality, James had become adept at sidestepping unnecessary expenses. To reduce costs, Elizabeth’s christening was held on November 28, when bitter cold and inclement weather would ensure that attendance at the ceremony was kept to a minimum. Those guests who did accept the royal invitation were instructed to bring their own dinners. Ever on the lookout for ways to squeeze a profit from events, to ingratiate himself with his far more affluent neighbor to the south, James fawningly named his daughter for the venerable queen of England. He further nominated Elizabeth I as godmother to the child, as he had done for his son two years earlier, expecting by this means to receive a handsome present. But although the English queen had acknowledged the birth of James’s son with “a cupboard of silver overgilt, cunningly wrought,” as well as a set of magnificent golden goblets, this time no similarly expensive gift—in fact, no gift at all—arrived to commemorate his daughter’s christening. The notoriously stingy Elizabeth I knew a thing or two about thrift herself.

Even before the ceremony, the infant Elizabeth had been removed from her mother’s care and sent to Linlithgow Palace, about fifteen miles west of Edinburgh, to be raised by guardians. Queen Anne, who did not wish to be separated from her daughter, had objected vehemently to this arrangement, as she had two years previously when her firstborn, Henry, had been unceremoniously wrenched from her in similar fashion, but James, citing Scottish custom, had insisted. The king, who had himself been brought up by custodians when political upheaval forced Mary Stuart to abdicate, evidently did not consider a mother to be a necessary or even particularly helpful component in child rearing.*

So Elizabeth spent her early youth in the care of her guardians, Lord and Lady Livingston, who in effect became her surrogate parents. The royal establishment was small—Elizabeth had a wet nurse and a governess, and two of Lady Livingston’s female relations were marshaled to help look after the little princess and assist with the household accounts. In 1598, when Elizabeth was a toddler, her mother gave birth to another daughter, Margaret, who was again taken from the queen against her wishes and also sent to live with Lord and Lady Livingston. Elizabeth would hardly have remembered her younger sister, as Margaret lived only two years, making the separation even more heartbreaking for her mother. A second son, Charles, was born on November 19, 1600. Although the baby was so sickly that he was not expected to live—he was baptized that same day—Charles managed to rally and so he, too, was removed from his mother’s care.†

Lacking ready cash, James paid for his daughter’s upbringing with gifts of land and titles. Little Elizabeth’s expenses included satin and velvet from which to make her two best gowns, ribbon to trim her nightdress, and four dolls (charmingly, they were referred to as “babies”) “to play her with”—an indication of a comfortable if not particularly opulent environment. Far more important, her guardians must have treated their small charge with kindness and affection, as Elizabeth retained fond memories of her childhood at Linlithgow Palace and remained close to her wet nurse and adopted family well into adulthood.

This was Elizabeth Stuart’s life—sheltered, quiet, unremarkable—until she was six years old. And then there occurred an event that had a defining effect on her fate. For on March 24, 1603, her godmother, Elizabeth I, storied daughter of Henry VIII by Anne Boleyn, vanquisher of the fearful Spanish Armada, royal patron of William Shakespeare and Sir Francis Drake, the resolutely determined woman who had ruled England for an astonishing forty-five years, died at the age of sixty-nine. And Elizabeth Stuart’s father, the cerebral but ultimately timorous king of Scotland, ascended to the English throne as James I.

NO ONE IN ELIZABETH STUART’S long, full life would have more influence over her than her father. The singularity of his character is absolutely critical to understanding what was to come. And the key to fathoming James’s depths lay not within the confines of mutinous Scotland but in the far gentler, glorious realm to the south. For no ambition held greater sway over the king of Scots’ soul than to rule moneyed England after Elizabeth I. His entire career was spent chasing the rainbow of this one shining promise.

This aspiration may be traced to the hardships of his early existence. Poor James’s troubles had begun while he was still in the womb. When she was six months pregnant with him, his mother had been held at gunpoint while a gang of discontented noblemen led by her husband, Lord Darnley, dragged her favorite courtier, her Italian secretary David Riccio, screaming from her presence and then savagely murdered him. To the end of her days, Mary was convinced that she and her unborn child had been the true targets of the assassins’ wrath—that the shock from the attack had been intended to provoke a late-stage miscarriage. “What if Fawdonside’s pistol had shot, what would have become of him [her baby] and me both?” she demanded of her husband in the aftermath of the slaying.

Not unreasonably, this episode had a deleterious effect on Mary’s affection for her husband. In fact, she couldn’t stand him. When James was born three months later, on June 19, 1566, Mary, forced by the assassination of Riccio to negate rumors of the boy’s illegitimacy, summoned Darnley to an audience at court. “My Lord, God has given you and me a son, begotten by none but you,” she proclaimed, holding the baby aloft for all to see. “I am desirous that all here, with ladies and others bear witness.” She knew what she was doing; the infant’s resemblance to Darnley was unmistakable. “For he is so much your own son, that I fear it will be the worse for him hereafter,” she concluded bitterly.

James’s birth did not have a placating effect on his parents’ relationship. The expedient of divorce or annulment was raised as a serious possibility, but this turned out to be unnecessary when Darnley was conveniently murdered the following February by a group of his wife’s supporters, led by the earl of Bothwell. A mere three months later, in May 1567, Mary scandalously wedded her former husband’s killer, a union that obviously did nothing to dampen suspicions of her own involvement in Darnley’s death. In the event, it turned out to be an extremely short marriage. By June, Bothwell’s enemies, of which there were many, had gathered an armed force together to confront the earl. Mary’s second husband managed to elude capture but the Queen of Scots was not so lucky. Mary was arrested and confined to the remote island castle of Lochleven. On July 24, 1567, she was forced to abdicate in favor of her son, James. Ten months later, she slipped away from her prison disguised as a maidservant and fled to the dubious hospitality of her cousin Elizabeth I, who would hold her under house arrest for the next eighteen years before finally executing her outright.

James was crowned king of Scotland on July 29, 1567, just five days after his mother’s abdication. He was unable to swear the customary oath of office, being only thirteen months old and not yet capable of forming words, so two of his subjects, the earls of Morton and Home, pledged in his name to defend the kingdom and the Protestant faith. Afterward, to mark this solemn occasion, his government granted its new sovereign four servant girls, to serve as “rockers,” and a new wet nurse.

The young king of Scots was raised at Stirling Castle, northeast of Glasgow, by his guardians, the earl of Mar and his wife. Conscious of the heavy responsibility entrusted to them, the pair—particularly the countess—kept a stern eye on their charge. It appears that James spent much of his youth in acute fear of his foster mother; by his own account he trembled at her approach. “My Lady Mar was wise and sharp and held the King in great awe,” a Scottish courtier concurred. The royal education, which began when James was four years old, was overseen by George Buchanan, Scotland’s most renowned poet and philosopher. Buchanan, a fire-and-brimstone Presbyterian, was already in his sixties, brilliant, crusty, and impatient, when he undertook to tutor the child king. It was rather like having Ebenezer Scrooge as a schoolmaster. Buchanan had him reading Greek before breakfast, followed by a full morning of history heavy on treatises by authors like Livy and Cicero. After lunch, he struggled with composition, mathematics, and geography until dark. “They made me speak Latin before I could speak Scottish,” James scrawled mournfully in one of his exercise books when he was old enough to write. Unfortunately, warmth and affection, the customs of polite society, and fun—Presbyterians did not much approve of fun—were not incorporated into James’s curriculum.

The result of all of this gloomy, concentrated instruction was that James grew up to be perhaps the best-educated monarch in Europe—and one of the loneliest. When he was only eight years old, “I heard him discourse, walking up and down in [holding] the old Lady Mar’s hand, of knowledge and ignorance, to my great marvel and astonishment,” a visitor to the court reported. By the time he was eighteen, it was judged by an envoy that “he dislikes dancing and music… His manners are crude and uncivil and display a lack of proper instruction… His voice is loud and his words grave and sententious… His body is feeble and yet he is not delicate. In a word, he is an old young man.”

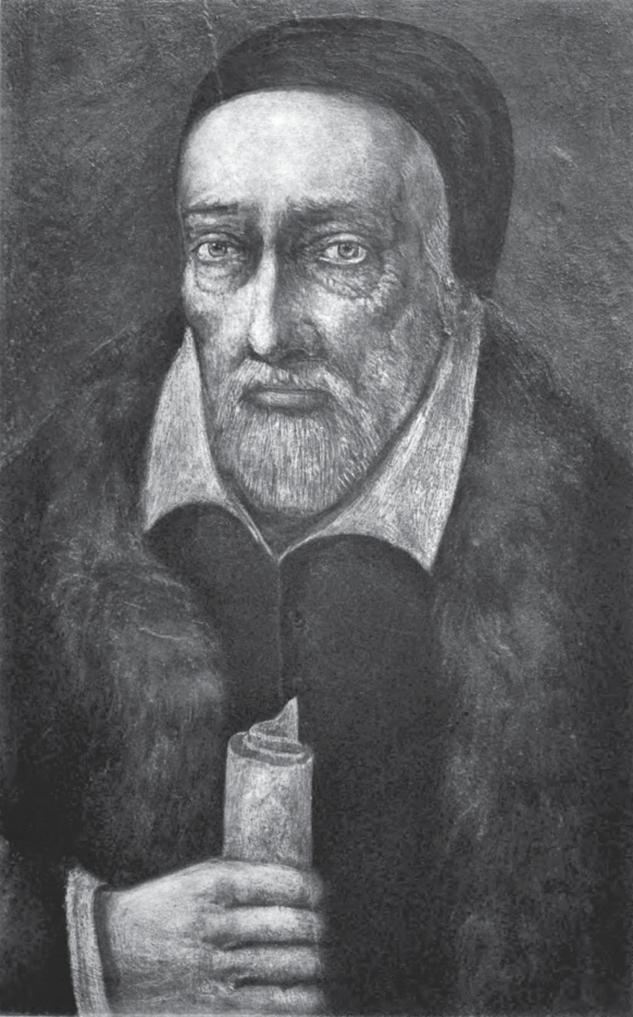

James as a boy

… and his crusty tutor, George Buchanan

Like others of his faith, his tutor Buchanan had a poor opinion of women in general and of his former queen, the Catholic Mary Stuart, in particular. So from a very early age, along with his Latin, James learned that his mother was a whore and a murderess who had engaged in such “malicious actions… as cannot be believed could come from the wickedest woman in the world,” a witness to his educator’s methods reported. Buchanan’s diatribes in combination with James’s own experience of the fearsome Lady Mar may have colored the king of Scots’ views of the fairer sex.* He had his first homosexual affair when he was thirteen, with his thirty-year-old cousin Esmé Stuart, Seigneur d’Aubigny, recently arrived from the court of Henri III, king of France (also homosexual), and his intimacy with handsome young men persisted into adulthood, despite his marriage to Anne.

In retrospect, it is easy to see the Seigneur d’Aubigny’s appeal. “That year [1579] arrived Monsieur d’Aubigny from France, with instructions and devices from the House of Guise [Mary Stuart’s relations], and with many French fashions and toys,” reported James Melville, one of the Presbyterian ministers, glumly. The young king of Scotland was fascinated by this engaging French relation who treated him like an adult rather than a sheltered schoolboy and who taught him the sort of colorful swear words beloved by adolescent males throughout the centuries. It was d’Aubigny’s task to insinuate himself into James’s life and favor and he succeeded admirably with the socially awkward teenager. “At this time his Majesty, having conceived an inward affection to the said lord Aubigny, entered into great familiarity and quiet purposes with him, which being understood to the ministers of Edinburgh, they cried out continually against… saying it would turn his Majesty to ruin,” observed one of James’s secretaries.

But more troublesome than the profane language and bawdy jokes, the fast horses, the open caresses, the afternoons spent in racing and hunting, and the other delightful activities that stretched long into the night was a more subtle form of seduction that d’Aubigny also brought with him from France: an idea. Specifically, the notion of the divine right of kings, which stated that as the person chosen by God to rule over an earthly kingdom, a monarch had absolute authority over his subjects—all of his subjects, including the ministers of the church.

This was not at all what the browbeaten James, until only recently chained to his lesson book by Buchanan, had been taught. The Presbyterians, particularly the outspoken ministers of Edinburgh, very conveniently believed that (having been preordained by God as saved) they wielded ultimate authority over temporal affairs, which included telling the king what he could and could not do.

D’Aubigny could not have recruited a candidate more receptive to the autocratic French philosophy than the adolescent king of Scotland. Raging hormones combined with a strong intellect and the euphoria of first love soon gave way to open rebellion as James, accustomed to reasoning through long, obscure passages from Greek and Roman scholars, intuitively grasped that in this doctrine lay the instrument of his emancipation. Nor could his ministers argue their former protégé out of his epiphany. So well educated had James become that he could rebuff every objection and answer every remonstrance—and he could do it in Latin.

By the end of d’Aubigny’s first year in Scotland, James had raised him to duke of Lennox and showered him with gifts of land and castles. The next year, d’Aubigny, with James’s tacit support, engineered the downfall of the once all-powerful earl of Morton.* Morton, who had run the kingdom for a decade, was subsequently accused of treason and executed, with d’Aubigny promoted in his place. The church elders in Edinburgh, used to a docile sovereign, were stunned to find a French Catholic and partisan of the reviled Mary Stuart suddenly the reigning influence behind James’s government. (D’Aubigny, attuned to the politics of his adopted realm, made a point of converting to Protestantism, but this fooled no one.) “At that time it was a pity to see so well brought up a Prince… be so miserably corrupted,” lamented Melville.

But as the king very quickly discovered, theories about who had a right to command were often challenged by those with perhaps a smaller claim to legitimacy but the advantage in ferocity, numbers, and weapons. Less than a year after d’Aubigny’s ascension to power, in August 1582, James was out on a hunting trip when he was invited to visit Ruthven Castle, a fortress owned by a Protestant nobleman. Unbeknownst to the king, his host, jealous of d’Aubigny’s rise, had banded together with a number of like-minded gentlemen (including the Edinburgh ministers) to overthrow the favorite. Separating James from his French courtier and holding him hostage against their demands represented the first step in this revolt. Informed the next morning when he tried to leave that he was not a guest but a prisoner, sixteen-year-old James burst into tears.

And in this reaction lay the crux of the dilemma facing the young sovereign. As a scholar, James was fearless and would remain so throughout his life.* But as a soldier, he was hopeless. Although frequently obliged to raise troops to defend himself over the course of his reign, James rarely rode with his forces. More often than not, when threatened, he would take the expedient of hiding in a tower or behind a locked door. On those few occasions when he did sally forth with his men, he tended to sally back to safety very quickly. “The king came riding into Edinburgh at the full gallop, with little honor,” sneered a contemporary after witnessing his sovereign turn tail and flee pell-mell from his enemies after one such skirmish. It was to be James’s curse that he had no taste for battle, and inevitably shied away from violence, because he lived in a kingdom wedded to violence.

His subjects were quick to capitalize on their sovereign’s weakness. The proprietor of Ruthven Castle and his cohorts held James against his will for nearly a year, during which time he was forced to accede to all the Presbyterian opposition’s demands. Although the king eventually escaped in June 1583 with the help of his French relatives and the Catholic clans, it was too late to save d’Aubigny, who had long since fled the kingdom. Nor, once free, could James recall his favorite. Heartbreakingly for the seventeen-year-old king, his cherished companion died in Paris that same June. “And so the King and the Duke [d’Aubigny] were dissevered, and never saw the other again,” reported Melville with satisfaction.

Sadly, this pattern of aggression was to be repeated many times during James’s reign. Because Scotland was so divided, no matter what stance the king took, he inevitably provoked opposition from one faction or another. The disgruntled party knew that the surest way to seek remedy was not to outmaneuver James politically but simply to seize the king bodily and force him to back down. In November 1585, James was again accosted and held hostage by the Presbyterians (whom he never forgave for the loss of d’Aubigny), this time, humiliatingly, in his own castle in Stirling. As late as 1600, when he was in his midthirties and had been married for over a decade, the king, out on a hunt, was lured to a house in Perth by an attractive young man who subsequently threatened his sovereign with a dagger. James only escaped by bawling, “I am murdered. Treason!… help, help!” out the window.

Small wonder, then, that from a very early age, James looked longingly to England, where Elizabeth I, ferociously protected by her inner circle and having earned the respect and love of the majority of her people, ruled for decade after decade in comparative peace and wealth. The queen had enemies, it was true, but for the most part, they came from abroad, the Spanish Armada being the prime example. Nobody tried to take her captive while she was out hunting.

James eventually settled on a two-pronged approach in his effort to succeed Elizabeth. First, he actively cultivated her friendship with a view to maintaining amicable relations with England no matter what the provocation. This expedient was somewhat put to the test in the aftermath of his mother’s beheading, but the king of Scotland, ever the intellectual, found a way to rationalize his passivity: “If war should ensue, the old quarrels and animosity would be revived to that degree that the English would never accept him [James] for their Prince,” the Scottish ambassador to England explained. “But she [Mary] being now executed for such good and necessary causes, it will be more for his honor to see how he can moderate his passion by reason.”

Second, and just as important, it was necessary for James to survive his dangerously cantankerous Scottish subjects long enough to inherit Elizabeth’s placidly wealthy ones. This feat he achieved primarily by eschewing extremism in any form and by mastering the useful art of dissembling. The king “made many fair promises unto them, and never keeped a word,” the Edinburgh ministers complained bitterly at one public audience.

As the years rolled by and James reached adulthood, married, and had children of his own, he must often have wondered whether the queen of England was ever going to die. But mortality darkens the bedchamber of even a sovereign as indomitable as Elizabeth I and at long last, in 1603, when he was thirty-seven years old, James succeeded to the prize he had worked so hard to achieve. By the time he left Scotland for England to claim his throne, he had become a man who habitually said “Yes” but almost always meant “No.” This was a technicality that his daughter, who was too young to have known her father during his perilous past, perhaps never fully appreciated.

THE ALACRITY WITH WHICH James possessed himself of his new kingdom—he dashed off to England on April 3, a mere ten days after Elizabeth I’s death, with instructions for the rest of the family to follow at the earliest opportunity—set off a domestic upheaval that must have been bewildering to his six-year-old daughter. Within two months, Elizabeth Stuart’s small store of possessions was packed up and she was whisked away by her mother and elder brother, Henry (her younger brother, Charles, being deemed too sickly to travel), from her modest household at the castle of Linlithgow to begin the journey south.*

The royal family’s procession to England, which left on June 1, 1603, was as stately as could be mustered on such short notice. From a way station in Yorkshire (a little less than halfway between Edinburgh and London), James ordered “the sending… of such Jewels and other furniture which did appertain to the late Queen [Elizabeth I]… and also coaches, horses, litters, and whatever else you shall think meet” for his wife’s use. A posse of aristocratic ladies, both English and Scottish, swarmed to Anne’s side to keep her company on the sojourn, look after her needs, and enjoy the general revelry. Elizabeth was awarded a new, very grand English chaperone, Lady Kildare, who was responsible for riding with her small charge and seeing to the princess’s welfare along the way. Often the queen’s party outdistanced her daughter’s, as, being a child, Elizabeth was easily tired. On these occasions, Anne would arrange to wait for her at a spot farther ahead so that Elizabeth could travel at a more moderate pace.

Although there is no record of the princess’s impressions of this journey, the concessions Anne made to her daughter would indicate that perhaps Elizabeth was feeling a little overwhelmed. It took a month to rendezvous with the king—a month that consisted every day of new places and new people, of feasts and long-drawn-out public ceremonies, of rush, rush, rush and ride, ride, ride. On June 15th, the procession alighted in York, where the new queen and her children were treated to a “Royal Entertainment” at which Elizabeth received “a purse of twenty angells [sic] of gold”; from there, they passed to Grimson and Newark before straggling into Nottingham on the 21st. At this point any ordinary six-year-old would have tried the patience of even the fondest parent, and this seems to have been the case, as Elizabeth and Lady Kildare broke off from the rest of the procession for a few days. But the respite was brief, as the family was due in Windsor by the first of July, where James had arranged to dub his eldest son a knight. The ceremony called for much pomp and splendor; even Elizabeth’s small suite was required to make a regal entrance. “The young princess came [into Windsor], accompanied with her governess, the Lady Kildare, in a litter with her, and attended with thirty horse,” admired a member of the court. “She had her trumpets and other formalities as well as the best.”

The knighting ceremony was the first time since coming to England that the family (with the exception of Charles) was together at a state event, and as such served as a formal introduction to the kingdom. Elizabeth did not have a significant role in the proceedings but was permitted to stand in the great hall and peek at the brilliant, bejeweled company as they sat down to feast. The riches on display were quite outside the experience of its royal participants; to host a gala of this magnificence simply would not have been possible in Scotland, not even if every clansman had brought his own dinner. “There was such an infinite company of Lords and Ladies and so great a Court as I think I shall never see the like,” exclaimed one of the guests. Henry acquitted himself well and it was clear that the kingdom was relieved to have acquired so attractive a crown prince after decades of uncertainty over the succession. “I heard the Earls of Nottingham and Northampton highly commend him [Henry] for his quick witty answers, princely carriage and reverence performing obeisance at the altar: all which seemed very strange unto them and the rest of the beholders, considering his tender age,” avowed another of the company. James could congratulate himself that the long years of privation and fear, not to mention groveling to Elizabeth I, had been worth it.

The contrast between the royal family’s new economic standing and their previous fortunes was so pronounced that it seems to have taken some getting used to. When plague struck London and it was judged best to send Elizabeth and Henry away to a castle in the countryside as an interim precaution, James initially provided his children with a staff of 70 domestics—22 upstairs, 48 downstairs—to meet their needs, far more than had waited on them in the past. But this was evidently considered inadequate by English standards, for within a week he was persuaded to increase the number of their servants to 104, and by October the children’s domestic staff had reached 141. The king seems to have had a similar difficulty reconciling his long-term training in austerity with the riches and dainties now available to him. “Whereas ourself and our dear Wife the Queen’s Majesty, have been every day served with 30 dishes of meat; now hereafter… our will is to be served but with 24 dishes every meal, unless when any of us sit abroad in State, then to be served with 30 dishes or as any more as we may command,” he decreed in one of the first ordinances he issued in England. Old habits die hard.

But for Elizabeth, who was too young to have been trained in the ways of penury, the transition to luxury was much easier. She had always lived with guardians, and this was the case also in England. By October 1603 a suitable pair had been found: Lord and Lady Harrington, great favorites of James and Anne’s. (Unfortunately, Lady Kildare’s husband had been accused of plotting against the government, so she was let go.) Lady Harrington had a lovely twelfth-century manor house called Coombe Abbey, formerly a monastery, in Warwickshire, about 100 miles northwest of London. Possessed of its own bell tower and moat and nestled on some 500 private acres that included formal gardens, an orchard, and a substantial lake, all surrounded by pristine English woodlands perfect for hunting, this imposing estate became Elizabeth’s new home.

Of course, the care and education of a princess of England in such a fine old abode required the procurement of a commensurately impressive household, and James did not stint on his daughter’s behalf. Elizabeth was allotted £1500 a year just for her meals. She was given twenty horses for her stable, so she would have something to ride, and a small army of groomsmen to care for them. She had her own doctor, three ladies-in-waiting, two footmen, a personal French maid, a seamstress, a dancing instructor, tutors in French and Italian, and a host of pastry chefs, cooks, and servers. Her music teacher, Dr. John Bull, whom she shared with Henry, was paid forty pounds a year to train his small pupil. He must have found his duties light, as there is evidence that he had the leisure to compose an early version of “God Save the King,” the English national anthem, in his spare time.

It wasn’t simply the affluence of her immediate surroundings but the manner in which she was treated that most bespoke the difference between Elizabeth’s childhood in Scotland and her life in England. On April 3, 1604, the seven-year-old made her first official visit to the neighboring town of Coventry. Her reception there is illustrative of the vast improvement in her circumstances. “The Mayor and Aldermen with the rest of the Livery rode out of the town in their scarlet gowns,” the official report of this interesting event recounted. “The Mayor alighted from his horse, kissed her hand, and then rode before into the City… a chair of state was placed at the upper end of the room, in which her Highness dined; from whence, having finished her repast, she adjourned to the Mayoress’s parlor, which was fitted up in a most sumptuous manner for her reception.”

It was an existence of the type portrayed in a fairy tale or novel—Sara Crewe from A Little Princess, only without Miss Minchin, as Elizabeth’s guardians were solicitous and responsible.* She had other children to play with, saw her brothers (Charles arrived in October 1604) and parents regularly at holidays, and received letters and gifts from them. She was a pretty, bright little girl who felt loved and valued and consequently reciprocated the affection bestowed on her. “With God’s assistance, we hope to do our Lady Elizabeth such service as is due to her princely endowments and natural abilities; both of which appear the sweet dawning of future comfort to her Royal Father,” her guardian Lord Harrington wrote to one of his cousins.

The only shadow to fall on the royal family’s otherwise bright prospects occurred in November 1605, when Elizabeth was nine years old. A small group of radical Catholic gentlemen, upset by James’s rejection of a petition for “Liberty of Conscience”—the right to practice their religion openly—resolved to avenge themselves by a chilling act of terrorism. Led by Guy Fawkes, a Flemish former soldier specifically imported for the job, they decided to assassinate the king, his young sons, and other representatives of the government by blowing up Westminster Castle on the first day of Parliament. According to the official report of this plot by a member of the French royal council, the conspirators reasoned that “the King himself might by many ways be taken away [murdered], but this would be nothing as long as the Prince [Henry] and the Duke of York [Charles] were alive: again, if they were removed, yet this would advantage nothing so long as there remained a Parliament.” To effect this feat of political mass murder, the group planned to place barrels of gunpowder underneath Westminster and then set them on fire during the opening session, from which frightening premise the intrigue was ultimately dubbed the Gunpowder Treason.

The radicals had first intended to position the explosives by tunneling under their target, but the thick walls of the palace proved difficult to penetrate. Instead, by happy chance (for them), in March 1605, they found that a neighboring house had a cellar ideal for their purposes. “Such was the opportuness of the place (for it was almost directly under the Royal Throne) that so seasonable an accident did make them persuade themselves, that God did by a secret Conduct favor their attempt,” the French report continued. As the first session of Parliament had been put off until November 5, this gave Guy Fawkes and his men nearly eight months to accumulate the necessary firepower.

During those eight months, it occurred to the group that it behooved them to have a plan in place to seize control of the kingdom after the ruling party had been annihilated. Recognizing that they would need some form of political legitimacy, they determined to make use of Elizabeth, who they concluded would be easy to capture and intimidate since she was young and female. “Therefore the Conspirators did again repeat their consultation, and some were appointed who, on the same day that the Enterprise was to be Executed, should seize upon the Lady Elizabeth… under pretence of a hunting match… Her they decreed publickly to proclaim Queen.”

The plot was so horrifically audacious that it very nearly succeeded. The cabal was betrayed by an anonymous letter delivered to a member of Parliament, who turned it over to the Privy Council less than two weeks before the opening session.* But so cryptically was the warning worded that James’s ministers could hardly credit it. “For although no signs of troubles do appear, yet I admonish you that the meeting [of Parliament] shall receive a terrible blow, and shall not see who smiteth them,” the epistle darkly but inscrutably threatened. Uncertain what to do, the Privy Council waited until the king, who was away on a hunting trip, returned to London on November 1, a mere four days before the session was called, to show him this curious missive.

But James, whose Scottish experience of intrigues dwarfed those of his councillors, and who moreover delighted in tricky literary conundrums, took the warning very seriously. He puzzled over it for an evening and then ordered “that the Palace with the places near adjoining, should be diligently searched.” His investigators very quickly found the cellar the conspirators had appropriated, along with thirty-six barrels of gunpowder (hidden under stacks of wood and coal), and Guy Fawkes himself, with matches in his pocket.

The plot having been uncovered in time, a general warning went out and the rest of the band were soon discovered, rounded up, found guilty, and executed. News of his innocent ward’s proposed role in these proceedings gave Lord Harrington quite a shock. One “hath confessed their design to surprise the Princess in my house, if their wickedness had taken place in London,” he wrote to his cousin, obviously appalled. “Some of them say, she would have been proclaimed Queen.” As for Elizabeth, “this poor Lady hath not yet recovered the surprise, and is very ill and troubled,” her guardian continued. “What a Queen should I have been by this means?” the princess reportedly exclaimed in dismay. “I had rather have been with my Royal Father in the Parliament-house than wear his Crown on such condition.”

James I, king of England

By degrees the furor died down, and royal life returned to its previous peaceful, prosperous routine. But despite his having triumphantly foiled the plot, and the gratifying way in which the government subsequently rallied around him, it might well have occurred to James that perhaps being king of England wasn’t quite as inviolable as he had always supposed it would be.