11

The Visiting Philosopher

“IN MY TIME, WHICH WAS 1642,” reminisced a French physician who settled in Leyden and eventually became dean of the College of Orange, “there used in Holland to exist the following custom: the ladies of the Hague used to delight in going in boats from the Hague to Leyden or to Delft; they were dressed as women of the burgher class and mixed in the crowd so as to hear all that might be said upon the great ones of the earth, touching whom they tried to provoke all present to converse. Often they heard much that concerned themselves, and even—their manners being something rather extraordinary—they seldom returned without some cavalier having offered them his services. The said cavaliers, however, were, for the most part, terribly disappointed in their hopes of having made acquaintance with females of a certain kind, for when they landed from the boats, there was invariably a coach in waiting, which carried the fair adventuresses all alone,” the doctor snickered. “Elizabeth, the eldest of the Bohemian princesses, would sometimes join these parties,” he noted.

By the time Karl Ludwig returned to The Hague, in the fall of 1642, Princess Elizabeth was nearly twenty-four years old. It had been seven long years since the king of Poland had actively solicited her hand, and except for a brief scheme floated by her mother to marry her eldest daughter to a German duke in order to help Karl Ludwig’s war effort—a plan that unfortunately had to be abandoned when the prospective bridegroom died of fever before anyone had a chance to sound him out on the subject—she had had no other proposal. A highly intelligent woman, Princess Elizabeth must have known that her principal asset had always been her position as the niece of a rich and powerful uncle who might be coaxed to do something for his only sister’s eldest daughter, and that consequently her chances for marriage had decreased even more with the recent outbreak of civil war in England. Without the promise of English money or influence, she was simply one of four poor, landless sisters of superior breeding but dubious title whose religious affiliation precluded any alliance with a Catholic, a proviso that unfortunately significantly reduced the pool of potential suitors. Princess Elizabeth would have been starkly aware that she was rapidly approaching an age where, youth and childbearing being prized, she would no longer be considered desirable, and so she must steel herself to spinsterhood.

And this cannot have been a happy prospect for her, as Princess Elizabeth does not seem to have fit in particularly well at her mother’s court. The numerous responsibilities, both social and political, that daily claimed her attention seemed only to irritate her. “The life which I am obliged to lead, leaves me hardly disposition nor time to acquire the habit of meditation… Sometimes the interests of my family which I ought not to neglect, sometimes conversations and complaisances which I cannot avoid, lower this weak mind of mine with weariness or vexation that it is rendered useless for a long while,” Princess Elizabeth once confided in frustration. Translation: she often found herself bored into a stupor.

Small wonder, then, that she took whatever opportunity she could to escape into the outside world, to blend in anonymously dressed as someone other than herself. But it is highly unlikely that Princess Elizabeth took these boat trips simply to engage in some surreptitious coquetry. Rather, she used the barges as other people did, as the quickest means of getting to Leyden or Utrecht, where the elite universities in Holland were located.

For Princess Elizabeth had made herself into a scholar of note. Even the French doctor admitted it. “Wonders were told of this rare personage; it was said, that to the knowledge of strange tongues she added that of abstruse sciences; that she was not to be satisfied with the mere pedantic terms of scholastic lore, but would dive down to the clearest comprehension of things; that she had the sharpest wit and most solid judgment… that she liked surgical experiments, and caused dissections to be made before her eyes… her beauty and her carriage were really those of a heroine,” he revealed.

Reports of the princess’s intellectual accomplishments were in no way hyperbole. Nor was she the only woman in Holland to have succeeded in infiltrating the heretofore almost exclusively male world of scholarship. In her pursuit of learning, Princess Elizabeth had obviously been inspired by the achievements of her good friend, the remarkable Anna Maria van Schurman.

Anna Maria was a prodigy. She was a gifted artist and singer as well as a voracious reader and formidable intellect. She had been taught Latin and Greek as a child by her father, who early recognized her abilities and encouraged her in her studies. Later, the rector of the University of Utrecht, impressed by her erudition, allowed her to attend lectures (although she was required to sit separately from the rest of the all-male class, in a small alcove shielded by curtains) and personally instructed her in Hebrew and theology. “Desire for knowledge absorbed me,” she confessed simply.

Princess Elizabeth met Anna Maria through Gerrit van Honthorst, who, impressed by her artistic talent, brought her into his school, where she took lessons with the queen of Bohemia’s children. Eleven years older than Princess Elizabeth, Anna Maria had already mastered Ethiopian and produced a grammar as a study guide for others, and was renowned throughout Europe for the publication of a Latin treatise in defense of women’s higher education. “My deep regard for learning, my conviction that equal justice is the right of all, impel me to protest against the theory which would allow only a minority of my sex to attain to what is, in the opinion of all men, most worth having,” she wrote in 1637 in a letter to an eminent theologian, explaining her motivation in writing the pamphlet. “For since wisdom is admitted to be the crown of human achievement, and is within every man’s right to aim at in proportion to his opportunities, I cannot see why a young girl in who we admit a desire of self-improvement should not be encouraged to acquire the best that life affords,” she concluded. Princess Elizabeth, whose passion for learning was considered excessive by her family (they signaled their amusement by assigning her the nickname “la Grècque,” the Greek), recognized Anna Maria as a kindred spirit and looked up to the older woman as a role model. “Despising the frivolities and vanities of other princesses, she raised her mind to the noble study of the most lofty science; she felt herself drawn to me by this community of tastes and interests, and testified her favor as well by visits as by her gracious letters,” Anna Maria remembered.

Her eldest daughter might have disparaged the diversions of the Winter Queen’s court—the endless rounds of hunting, balls, and concerts that defined the upper echelons of Dutch society—but in fact, her mother’s presence at The Hague, along with the household of the prince and princess of Orange, contributed greatly to the blossoming intellectual environment. The encouragement and patronage of these two courts attracted some of the best minds in Europe to Holland. The prince of Orange’s secretary was an accomplished poet and scholar, and although he referred to his position as “his golden fetter,” it nonetheless provided not only his livelihood but also access to and influence within the international academic community. The queen of Bohemia, too, was known to take an interest in all the latest developments in the arts and sciences, and hosted many of the leading intellectuals at her salons. “This town [The Hague] can certainly compare with the first towns in Europe,” boasted the same French physician, “and in my time was proud of possessing three Courts: firstly, the Court of the Prince of Orange, a military court, where might be seen above two thousand noblemen and their suite of soldiers decked out in buff doublets, with orange scarves, high boots, and long sabers, and who were this Court’s chief ornament; secondly, the Court of the States-General, full of provincial deputies and burgomeisters, and representatives of the aristocracy, in black velvet coats, broad collars, and square beards; lastly, the Court of the Queen of Bohemia, which seemed that of the Graces, seeing that she had four daughters, at whose feet all the beau monde [fashionable society] of the Hague came to depose their homage, and whose talents, beauty, and virtues were the subject of all men’s talk.”

And so it was that when the eminent French philosopher René Descartes, looking for the solitude necessary to his work and an atmosphere of intellectual freedom, decided to move to Endegeest, right outside Leyden, in the early 1640s, it was more or less inevitable that he would one day end up on the Winter Queen’s doorstep.

PHILOSOPHY IS ONE OF those subjects, like astrophysics and neurosurgery, that are not for the fainthearted. To delve into the absolutes of the human experience, to seek to advance the progress of enlightenment first expounded by the likes of the revered Aristotle and Plato, to search for the answers to the profound questions of the universe, often at the risk of deadly reprisal from entrenched powers, requires not only brilliance and tenacity but a deep sense of purpose. But even among this select fraternity, Descartes stands out. From him did we get practical discoveries like coordinates in geometry and the law of refraction of light. But what he really did was to shake loose the human mind from the shackles of centuries of stultifying religious orthodoxy by creating an entirely original approach to reasoning: the Cartesian method. You know you’ve gotten somewhere when they name a whole new branch of science after you.

René Descartes was born into a family of minor regional nobility in a small town in western France near Poitiers in 1596, which made him only a year or so older than the queen of Bohemia. He had been quite sickly as a young child, so when he was nine and his father sent him to the nearby Jesuit school, he instructed the headmaster, who was a close friend, to have a care for his son’s health. Consequently, Descartes’s academic experience fell quite outside the boundaries of traditional instruction for the period. Where his fellow students were required to awaken early each morning and attend classes led by dreary masters who often resorted to scoldings or beatings if a pupil failed to absorb the material, Descartes was allowed to sleep late and stay in bed reading as long as he liked, a privilege of which he took full advantage and which instilled in him the lifelong habit of rarely rising before the noon meal. As a result, and possibly alone in the entire history of Jesuit school training, Descartes actually enjoyed his years at the seminary and always remembered them fondly. As he was a brilliant student who was particularly gifted in algebra and geometry, this innovative approach produced a higher-quality education than what he would have received if he had been subjected to the usual routine. “I had been taught all that others learned,” he observed, “and, not contented with the sciences actually taught us, I had, in addition, read all the books that had fallen into my hands… [It was like] interviewing the noblest men of past ages who had written them.”

He left school at the age of eighteen and, intent upon experiencing “the great book of the world,” as he called it, determined to travel. Somewhat inexplicably for a young man whose talents tended so obviously to the cerebral, he chose to satisfy his craving for new people and places by enlisting in foreign armies. Again, his sojourns in the military, like his time spent at the Jesuit school, differed substantially from that of the common soldier’s. While there is evidence that he could handle his sword, he does not seem to have used it very often. It’s also unclear how frequently (if ever) he actually went into battle, although he was usually stationed near one. Moreover, as a gentleman knight of small but independent means, Descartes considered his valet to be as vital a component of his equipage as his bayonet, and generally camped out in a warm, comfortable room at a local inn where he could keep to his preferred regime of ten uninterrupted hours of sleep, followed by lying in bed and thinking until noon. Nor during those rare periods of the day when he condescended to dress and go out did Descartes waste much time on military affairs. Dismissing his fellow officers as dissolute louts, he instead made a point of seeking out all the leading mathematicians and academics in the area and dazzling them with his knowledge of algebra and geometry, and in this way obtained an ever-increasing circle of learned friends and admirers.*

It was in November 1619, during one of these intervals of semi-active service (when, ironically, he was attached to the imperial army under General Buquoi, who was fighting against the king and queen of Bohemia), that Descartes had his great epiphany. It came to him (where else?) in bed as a dream that most of what he had learned in school was incorrect and that in order to rectify these errors, it was going to be necessary to start all over again from the beginning, this time using the sort of rigorous proofs that worked so well in logic and mathematics. “As for the opinions which, up to that time, I had embraced, I thought I could not do better than resolve at once to sweep them wholly away, that I might afterwards be in a position to admit either others more correct, or even perhaps the same when they had undergone the scrutiny of Reason,” he later wrote. From that moment on—and here was the big break with accepted wisdom—Descartes would apply this objective, logical approach to every aspect of life, including the really tricky ones, like the existence of God, the relationship of the mind to the body, and the nature of consciousness.† This is where Cogito, ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”) comes from; his ability to reason was, to Descartes, the one irrefutable truth that he could rely upon and on which he would in the future strive to rebuild all human knowledge, “like one walking alone and in the dark.”

Descartes spent the next period of his life, through his twenties and into his thirties, refining his methodology with the intention of publishing his doctrine. Although he gave up the life of a soldier, he continued to wander restlessly across Europe, seeking out mathematicians and philosophers wherever he went and working on his treatise. He had completed a first draft and was just about to send it off to a publisher in France when the news broke that the astronomer Galileo had been condemned by the Inquisition for supporting the thesis, first advanced by Copernicus, that the earth went around the sun, and not the other way around. Despite going down on his knees and recanting his views, the distinguished scientist had been sent to prison, where, as part of his punishment, he was required to repeat seven psalms of contrition aloud every week for the next three years.

René Descartes

Galileo’s conviction came as a terrible shock to Descartes, who, as a devout Catholic and a great admirer of the Jesuit order, had been hoping to use the principles of logic and mathematics to reconcile the Church to scientific inquiry. “I could hardly have believed that an Italian, and in favor with the Pope, as I hear, could be considered criminal for nothing else than for seeking to establish the earth’s motion,” he wrote, almost in despair, to the friend in France to whom he had been about to entrust his own manuscript. “I thought I had heard that… it was constantly being taught, even at Rome; and I confess that if the opinion of the earth’s movement is false, all the foundations of my philosophy are so also, because it is demonstrated clearly by them. It is so bound up with every part of my treatise, that I could not sever it without making the remainder faulty,” he concluded despondently. Descartes was so terrified of courting a similar fate that in the immediate aftermath of Galileo’s condemnation in 1633, he seriously contemplated destroying all of his notes and papers.

But despite his fears, he couldn’t let it go, and in 1637 he summoned up the courage to publish his first major work, A Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting the Reason and Seeking Truth in the Sciences, which he followed up in 1641 with a second volume, Meditations Concerning the First Philosophy in Which Are Demonstrated the Existence of God, and the Immortality of the Soul. Both tracts were widely circulated throughout Europe, but it was the first, A Discourse on the Method, that vaulted Descartes into the public consciousness and made his name as a brilliant philosopher.

And so it was as something of an international celebrity that he first walked into the queen of Bohemia’s drawing room and there met her eldest daughter, Princess Elizabeth.

THERE IS NO RECORD of what occurred during this first interview, but by the spring of 1643, forty-seven-year-old Descartes, who had been made aware through an intermediary that twenty-four-year-old Princess Elizabeth had read his work and wished to discuss it with him, was sufficiently interested to make an impromptu visit to The Hague specifically to talk to her. Unfortunately, the princess was with her mother at the royal hunting lodge in Rhenen on the day the philosopher chose to call, an oversight that prompted a gracious note of apology from his absent hostess. “Monsieur Descartes,” Princess Elizabeth wrote on May 6, 1643, “I have learned with much pleasure and regret the intention you had of seeing me a few days ago, and was equally touched by your kindness in wishing to converse with one so ignorant… and by my misfortune in losing so profitable a conversation.” She went on to say that she had questions about some of his theories and had been encouraged by her tutor to approach him directly. In particular, she had trouble understanding how metaphysics controlled emotions and bodily functions, and so, “I have driven from my mind all other considerations than that of begging you to tell me how the soul of a man can determine the motions of the body to perform voluntary actions (being but a thinking substance). For it seems that all determination of movement comes from the force exercised on it… Therefore, I ask for a more particular definition of the soul… that is to say, of substance separate from its action, thought.”*

Although this was clearly not the ordinary “So sorry to have missed you!” society missive, Descartes, in his response, seems to have assumed that her position outweighed her intellect, and he elected to toady rather than teach. “The favor with which your Highness has honored me in allowing me to receive your commandments by letter is far greater than I could ever have dared hope,” his fawning reply began. “And it makes my defects easier to bear than the one event that I would have fervently wished for, to have received them from your own mouth… seeing a discourse more than human come from a body so like those painters give to angels, I would have been in the same rapture it seems must be those who, coming from earth, enter for the first time into heaven,” he continued, before fobbing her off with an answer that even he noted was not “entirely satisfactory.”

He was right; it wasn’t. “Your kindness is shown, not only in pointing out and correcting the faults of my reasoning, as I had expected,” Princess Elizabeth shot back on June 10, “but also to render their recognition less vexatious you try to console me—to the prejudice of your judgment—by undeserved praises, which might have been necessary… if my being brought up in a place where the ordinary style of conversation had not accustomed me to hearing of them from people incapable of estimating them truly, and made me presume myself safe in believing the contrary of what they said,” she observed drily. (Translation: I expected more from you than sycophancy. I don’t have to consult a renowned philosopher to hear cheap compliments, I get them at home for free all the time.) “But as you have undertaken to instruct me I assure myself that you will explain to me the nature of immaterial substance and the manner of its actions and passions in the body.” (In other words, Take me seriously or not at all.) Signed (to take the sting out of it), “Your very affectionate friend, Elizabeth.”

It was some time before Descartes responded to Elizabeth’s letter. Possibly he was pondering how best to approach her. But in the end he evidently decided to take her at her word, because, through an intermediary, he sent her a math problem.

And not just any math problem: a lulu, one of those that had stumped mathematicians from the beginning of recorded time, one that had never before been solved. Except that Descartes had just solved it.

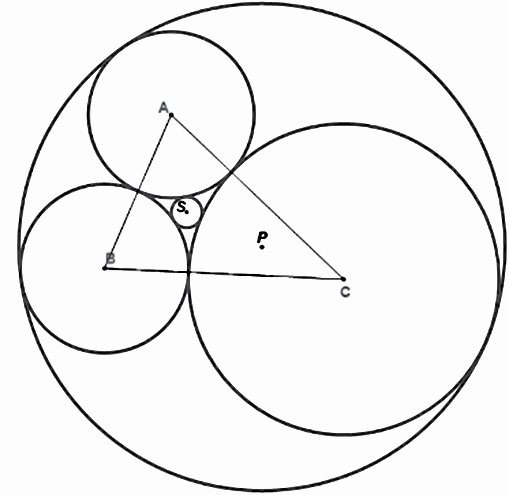

It’s called the kissing circles problem. There are three tangent circles (that is, all touching each other). Solve for a fourth circle that touches all of the other three.

He didn’t expect her to answer it. In fact, he almost immediately regretted sending it to her. “For the rest, I have much remorse for proposing the problem of the three circles to Madame the princess of Bohemia, because it is so difficult that it seems to me that an angel who had only the algebra taught her by [her math tutor] would not be able to solve it without a miracle,” he wrote on October 21 to the friend he had used to forward the puzzle in the first place. He knew that by sending it he’d been showing off a bit—he probably couldn’t resist—but it was also the gesture of respect that she had asked for. Mathematics was the measure by which Descartes judged the world. Those who grasped its principles and appreciated its beauty he held in high regard and counted among his intimate friends; those who did not were simply not taken as seriously.

And then she solved it.

It wasn’t an elegant answer, like Descartes’s, that solved for all possibilities, but she’d managed to work out a specific case. Princess Elizabeth herself was aware of this defect but decided to send her answer along anyway, “as a young angler might show an old fisherman his catch… For I know perfectly well that in my solution, there was nothing clear enough to result in a theorem,” she admitted in a letter of November 21, 1643. This problem, and Descartes’s solution (which was shown to her only afterward), “taught me more than I would have learned in six months with my tutor. I am very indebted to you… there are few things that I would not do to obtain the effects of your good will, which is infinitely esteemed by your very affectionate friend at your service, Elizabeth,” she concluded.

It was the turning point in their relationship. From a rocky start—condescension on his part, pride and frustration on hers—there now developed a warmth and closeness that rivaled physical intimacy. Descartes eventually took her step by step through his own solution to the kissing circles and used her queries to sharpen and refine his theories concerning the mind and the soul. “I have never met anyone who could so thoroughly understand all that is contained in my writings,” he enthused. “For there are many, even among the best and most highly instructed minds, who find them obscure, and I observe that almost all those who understand readily those things that pertain to mathematics are not capable of comprehending those that belong to metaphysics, and I can say with truth that I have met none except your Highness to whom both are equally easy.” He dedicated his next work, The Principles of Philosophy, published the following year, to her, and the inscription was so obviously heartfelt that it prompted comment. “Bless the good man!” the chatty French doctor said of Descartes. “He thinks only one man and one woman capable of entering into his doctrines, the physician Regius and the Princess of Bohemia.”

As for Princess Elizabeth, it would not be an exaggeration to say that the friendship she shared with Descartes—a friendship of ideas and analysis, a melding of minds and souls so different from the shallow pretense of her daily existence—was the most precious relationship in her life. To have secured the regard and affection of such a man, to have earned it through her own efforts, to be esteemed for who she was on the inside and not for her title, breeding, or connections—this was a source of great solace. There was no question of physical intimacy between a middle-aged Catholic philosopher and a Protestant princess twenty-three years his junior whose virginity might yet secure her an appropriate husband, but what they had together was more than most marriages could boast and that can only be described, without irony, as metaphysical love.

It was well for Princess Elizabeth that she managed to forge this intimacy with Descartes when she did, that she had someone she could trust to turn to during periods of sorrow or hardship. For life at her mother’s court at The Hague, never easy for her even in the good times, was about to become extremely challenging.

WHILE PRINCESS ELIZABETH WAS wrestling with algebra and geometry, the rest of Europe continued its armed struggles over religion and power. In the winter of 1642 again occurred one of those seminal events that resounded through the theater of war and that caused the dancers to pause momentarily in their steps. It was a loss not on the battlefield but in a quiet bedroom in Paris. There, on December 4, 1642, the architect of the French entrance into the German war, the man who had successfully, almost single-handedly, guided the kingdom through nearly two decades of serpentine political turmoil, Cardinal Richelieu, died at the age of fifty-seven.

He’d been sick for a long time, getting steadily weaker, as was true also of his sovereign, Louis XIII. The previous June both men had been so ill that the only way they could meet were in rooms that contained a bed for each to lie upon. By November Richelieu was coughing blood, and his physicians knew his end was near. “I pray God to condemn me, if I have had any other aim than the welfare of God and the State,” the cardinal was reported to have avowed just before his demise. At the time of his death, France, once apprehensive of being crushed between all-dominant Spain and the Empire, stood as the ascendant power in Europe. In nearly every direction—to the north, south, and east—the French had wrested territory away from the Habsburgs and pushed back their borders as a result of Richelieu’s tactics.

“A great politician has departed!” mourned Louis XIII when he was informed of the cardinal’s passing. Less than six months later, he too was dead, and the future of France—and, by extension, Europe—was left to his widow, the queen mother, Anne of Austria, who was regent for her two young sons, four-year-old Louis XIV and his younger brother, two-year-old Philippe, duke of Orléans.

But of course it was not France that occupied the thoughts and prayers of the queen of Bohemia’s court at The Hague at this time. It was to England and the civil war between Charles I and Parliament that the family’s anxious eyes were turned. They were right to worry. Charles’s war effort, feeble from the start, would likely have collapsed with the first battle were it not for the industry of one man whose exploits and expertise were so vital to the royal cause that they were analogous to possessing a secret weapon (or perhaps, more aptly, employing a ringer)—the king’s twenty-four-year-old nephew, Rupert.

THE ENERGETIC RUPERT’S EFFECT on his uncle’s military affairs was immediate and electric. No sooner had he and Maurice (who had accompanied his older brother to England to serve as his right-hand man) rendezvoused with Charles at Nottingham for the inauspicious planting of the royal standard, than Rupert, used to continental warfare and shocked by the overall lack of supplies and general ineptitude of the king’s troops, began to take over. The first order of business was obviously to train the cavalry they already had and then use them to secure additional men and armaments. This Rupert did so quickly that Charles made him not simply commander of the King’s Horse but general of the whole army. “That brave Prince and hopeful soldier, Rupert, though a young man, had in martial affairs some experience, and a good skill, and was of such intrepid courage and activity, that—clean contrary to former practice, when the King had great armies, but no commanders forward to fight—he ranged and disciplined that small body of men [Rupert had only 800 cavalry to begin with]—of so great virtue is the personal courage and example of one great commander. And indeed to do him right, he put the spirit into the King’s army that all men seemed resolved,” observed a member of Charles’s circle.

Having whipped his small team of men into shape in record time, Rupert, along with his white poodle, Boye, who was so intelligent that the opposition Parliamentarian soldiers believed the dog to be possessed by the devil, conducted a whirlwind tour through the countryside.* All those years of English lessons his mother had insisted on came in handy, as is evident in the letter he sent to the mayor of Leicester in advance of his arrival, which was typical of his approach. With great decorum, in the king’s name, he asked for £2,000, promising that it would be repaid at a more convenient period; signed the note “Your friend, Rupert”; and then added a postscript: “If any disaffected persons with you shall refuse themselves, or persuade you to neglect the command, I shall tomorrow appear before your town in such a posture, with horse, foot, and cannon, as shall make you know it is more safe to obey than to resist his Majesty’s command.” In this way, Charles’s 800 ragtag cavalry troops grew to 3,000 well-supplied horsemen in a single month.

As a result of his high spirits, military expertise, and seemingly limitless energy, Rupert very soon became the public face of the royal army to the rest of the kingdom, and particularly the enemy. The stories of his escapades were legion. It was said that he could travel fifty miles in a single day through hostile territory, win a battle, take prisoners, and be back at base camp by dinner. Once, interrupted at shaving by an enemy attack, he simply shrugged into his shirt, leaped onto his horse, and routed the opposition before returning calmly to his washbasin. A Puritan soldier reported that Rupert, out on a surveillance mission, met an apple peddler on the road near the enemy camp, bought the man’s entire stock on the spot, exchanged his coat and horse for the apple seller’s costume and cart, and arranged to meet him again later in the day. The prince then drove the cart to the heath where the Parliamentarian soldiers were stationed, sold them the apples, counted the number of their forces, perused the quality of their artillery, and then returned to the peddler. He rewarded the man with a golden coin and instructed him to go back to the opposition troops “and ask the commanders how they liked the fruit which Prince Rupert did, in his own person, but this morning sell them.”*

Rupert’s innovative methods, while condoned on the Continent (whose inhabitants had been at war for over two decades and who were therefore much more inured to intimidation), were considered highly unorthodox by his English victims. “The two young Princes, Rupert especially, the elder and fiercer of the two, flew with great fury through divers counties… whereupon the Parliament declared him and his brothers ‘traitors,’” affirmed a chronicler of the period.

Unfortunately, her younger sons’ highly public intervention in English affairs, so necessary to her brother’s war effort, put great stress on the queen of Bohemia and her court. Since his ascension to the throne, Charles I had been helping to support his sister and her family with an annual stipend of £12,000—not sufficient for grandeur but enough to cover basic expenses and keep food on the table. But with the advent of the civil war, Parliament held the purse strings, and its members declined to support the mother of the commander of His Majesty’s forces. Instead, through Puritan spies, they put the court at The Hague under surveillance.

This dilemma appears to have been anticipated by Karl Ludwig (whom Charles had also supported financially) and had in fact been at least partly responsible for his leaving England when he did. But despite Karl Ludwig’s attempts at neutrality, no money was forthcoming. The court at The Hague entered a period of increasing austerity. “We were at times obliged to make even richer repasts than that of Cleopatra, and often had nothing at our court but pearls and diamonds to eat,” Sophia recalled. To help cut expenses, the queen of Bohemia once again sent her two youngest sons, twenty-year-old Edward and sixteen-year-old Philip, to live with relatives in France, taking the risk that, with the reviled Cardinal Richelieu safely in the grave, there would be no plots against them.

She was right—in a way. Under the new regime, the queen of Bohemia’s younger sons were perfectly safe from the threat of espionage, prison cells, and sword thrusts. But not, as it turned out, from Cupid’s arrows.

LIKE HIS OLDER BROTHER Rupert, Edward had grown into a very attractive young man. He had long, flowing dark locks, a little pencil mustache, and a muscular body. He spoke French to perfection, having spent much of his later childhood and adolescence in France. He knew the manners and customs of Paris better than those of Holland. He liked the fashionable pleasures of the capital, which were much more sophisticated and entertaining than life at The Hague, but, alas, he had not the financial means to pursue them as fully as he would have liked. Still, as a nephew of the queen of England, herself a member of the French royal family and aunt to the boy sovereign Louis XIV, Edward managed to get around a little, and was invited to dinners. At one of these soirees he met a force of nature by the name of Anna de Gonzaga.

Anna was born in 1616, which made her nearly eight years Edward’s senior. She was both highly political and notoriously passionate and was as a result in possession of a reputation sorely in need of rehabilitation. The second daughter of the count of Mantua, Anna had been raised in a French convent where she and a younger sister were enjoined to take the veil by their father, who wanted to put all his resources into obtaining an advantageous marriage for his beautiful eldest daughter, Marie.* But the count of Mantua died before he could force his middle daughter to say her vows, and at twenty-one, Anna exchanged the nunnery for the French court. There, she met Henri, duke of Guise,† with whom she fell instantly, hopelessly, recklessly in love. “M. de Guise had the figure, the attitude and the manners of a Roman hero,” she sighed in her memoirs. Henri reciprocated her passion and shortly thereafter seduced her, promising her marriage in a letter signed in blood. His mother tried to put a stop to it by using her influence to promote him to archbishop of Rheims, a position he accepted. His new life in the Church did not, however, get in the way of his torrid affair with Anna, although it did come in handy, as he was able to bully a priest into marrying them secretly in a private chapel with no witnesses. Anna was so infatuated that she disguised herself as a man in order to follow her lover wherever he went, and she referred to herself as the duchess of Guise in letters to friends. It therefore came as something of a shock when Henri suddenly eloped with a French countess, whom he (legitimately) married in Brussels. By 1643, Anna was back in Paris, devastated and seriously on the rebound, when she met Edward.

She was wealthy in her own right but wanted respectability and a title; he was young, penniless, and malleable. He never had a chance.* “This princess,” reported another lady of the French court, “did not despise the conquests of her eyes, which were in truth very beautiful; but besides that advantage, she had that which was of more value, I mean wit, address, capacity for conducting an intrigue, and a singular facility in finding expedients for succeeding in what she undertook.” But of course Anna was a Catholic and Edward was a Protestant, and this wouldn’t do—to have the marriage accepted by French society, he would have to convert. As a matter of fact, it would be much to Anna’s credit if she could get the son of the queen of Bohemia, who was widely recognized as one of the staunchest Protestants in Europe, to accept the Catholic faith, and this may have contributed something to his allure. Edward weighed the advantages of a marriage to Anna—a brilliant life in Paris, money, a worldly, fascinating wife—against those of his religion—poverty, rootlessness, a mother he barely knew, and the generally uncertain existence that could be expected by the middle son of a deposed king—and took the deal.

They were married in April of 1645 and afterward Edward very publicly converted to Catholicism, accepting Communion at the hands of a popular priest in Paris. Anna was given the credit for this coup, and her career at court was assured. She and Edward set up housekeeping in Paris as the prince and princess of Palatine, where they were accorded honors and a status comparable to those assigned to foreign dignitaries, and Edward would go on to watch his wife become a political force in France. “She had so much intelligence, and a talent so peculiar for business, that no one in the world ever succeeded better than she did,” a French statesman concurred.

Edward and his new wife, Anna de Gonzaga

The news of Edward’s conversion and marriage fell upon the family court at The Hague like one of the ten plagues called upon the pharaoh by Moses in the Bible. His mother would have preferred that he take out his dagger and plunge it into her breast than to suffer the humiliation of having raised a traitor to the Protestant cause. Karl Ludwig, who had gone back to England, not to support his uncle’s cause, but to personally assure Parliament of his goodwill and lobby for the reinstatement of his income, was equally incensed, as Edward’s rejection of Protestantism played directly into Puritan fears that Charles I would call on Catholic forces to invade the kingdom. Moreover, as the nominal head of the family, Karl Ludwig should have been consulted before his brother entered into a marital alliance. To prevent further damage, he immediately ordered his youngest brother, Philip, to leave Paris, “where were only to be found either Atheists or hypocrites,” as he scornfully avowed, and return to the vigilant orthodoxy of The Hague.

Princess Elizabeth was, if possible, even more distressed than the rest of the family by what she considered to be a betrayal on Edward’s part. The sensational tidbit was picked up by the Dutch papers, and as might have been expected, they had a great deal of fun with it. The princess was used to adversity, even tragedy, but had always been firm in the family’s cause and clearly took her religion very seriously. The very public nature of the scandal mortified her. So used to turning to Descartes was she that, despite his being a devout Catholic who could not help but rejoice at Edward’s conversion, she poured out her heart to him. After first apologizing for not having answered an earlier letter as promptly as usual, “It is with shame that I confess the cause, since it has overthrown all that your lessons seemed to have established in my mind,” she continued, distraught. “I believed that a strong resolution only to seek happiness in the things which depend on my will would render me less sensitive to those which came from without, before the folly of one of my brothers made me feel my weakness. For it has disturbed the health of my body and the tranquility of my soul more than all the misfortunes which have yet happened to me.* If you take the trouble to read the gazette you must be aware that he has fallen into the hands of a certain sort of people who have more hatred to our family than love of their own worship, and has allowed himself to be taken in their snares to change his religion and become a Roman Catholic, without making the least pretence which could impose on the most credulous that he was following his conscience. And I must see one whom I loved with as much tenderness as I know how to feel, abandoned to the scorn of the world and the loss of his own soul (according to my creed).” Then, as if suddenly remembering that Descartes was a Catholic, she added quickly, “If you had not more charity than bigotry it would be an impertinence to speak to you of this matter, and if I were not in the habit of telling you all my faults as the person most able to correct them.”

This humble disclaimer notwithstanding, her correspondent took offense; the letter that came back was a very long, full-on defense of Edward’s conversion to Catholicism, for Descartes was as passionate about his dogma as she was about hers. “I cannot deny that I was surprised to hear of your Highness’s anger, even to the inconvenience of her health, by a thing that the greater part of the world finds right [bonne], and which for many forceful reasons render it excusable to the rest,” he began coldly. He then went on to scold her for her reaction and to put Edward’s behavior, and that of those who had advised him to convert, in the best possible light, although at the very end, possibly realizing that he had been harsh, he added: “It is with the ingenuousness and frankness that I profess to observe in all my actions that I also particularly profess to be, etc.” (which was the way he signed all his letters, implying yours truly, in your service, and so forth).

She had asked him always for honesty, and that is what he gave her: there was nothing of the courtier in this letter. Nonetheless, it took Princess Elizabeth several months to renew the correspondence. The reason for this is unclear, as certainly the events of 1646 were sufficiently distracting to take up so much of her attention that there was no time to dally in the world of metaphysics. Or it could have been that truth is subjective after all.