Chapter 3

WOLLEMIA NOBILIS

Ken Hill is a tall, softly spoken botanist with a Grizzly Adams beard, flecked with a surprising array of autumnal reds and browns. He mostly wears t-shirts and jeans and has the patient manner of a man with a pair of teenage children and who has spent years of researching the world’s slowest growing organisms—trees. On 22 November 1994 Allen and Jones took the tree material and a draft paper to Hill at Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens, confident in the knowledge that what they had been working on was a new genus. With all of the cuttings and cones that had been collected now in front of him, Hill knew that what was sitting on his desk was the most remarkable and botanically significant specimen that he had ever encountered.

To understand this part of the story required a visit to the herbarium and the grounds of the Royal Botanic Gardens. Hill had offered to introduce me to all the members of the family Araucariaceae that were growing there and to tell me everything he knew about their bizarre sex life. The herbarium is situated on one of the world’s best pieces of real estate—a headland that begins under the shadow of the political and legal heart of Sydney and ends jutting into the harbour at the Opera House. It was a steamy, rainy January day when we met in his office.

‘When I opened up the cone,’ Hill recalled, ‘I just thought, “This is amazing—this is a new genus. This is big news.” I had a chance to pull the cone apart. From the outside the seed-cone looked much more like an Araucaria cone than an Agathis. Inside it had more of the structure of Agathis but the seeds were different. I phoned Wyn the next morning to tell him, “Yes, it is new.”’

To show me what the password is to become a member of the Araucariaceae, Hill and I walked in the rain to the conifer section. Some of the dripping wet trees were barely recognisable to the untrained eye as conifers, with their soft rounded leaves and smooth trunks.

Araucariaceae range in height from ten metres to more than sixty. Their leaves are all spirally arranged and their seed-cones are hard and woody. Some have leaves shaped like savage daggers, with points like needles, others such as the Norfolk Island pine have tiny, dense, leathery leaves that form long cylindrical stems. One of my earliest memories as a child is pulling the stem out from the foot-long Norfolk Island pine needles at Manly Beach—like removing a sword from its sheath.

After a few minutes Hill found an elongated Araucariaceae pollen cone that had been soaked by the rain and broke it in half. He pointed at one of the cone’s hundreds of pollen sacs, each just a fraction larger than a pinhead. They looked like hundreds of minute squids impaled on tiny sticks. Every monkey puzzle tree, he told me, has the same structure in the architecture of the pollen sac. No matter which genus or species a monkey puzzle belongs to, its pollen cone identifies its place in the botanical kingdom as surely as if someone had carved the word ‘Araucariaceae’ to its trunk. ‘It is the fundamental difference between an Araucariaceae and the other conifer families,’ Hill said.

He explained on what basis botanists place some Araucariaceae into the genus Agathis and others into the genus Araucaria. One of the keys is the female seed-cone. It is in fact the seed-cone which has given Agathis its name. Agathis is Greek for a ball of thread, and the seed-cones are made up of hundreds of scales packed into a dense resinous ball.

When the cone is broken up a trained botanist can immediately divide the Araucariaceae family using the following rules. If the ovule sits on top of the scale, if one side of the seed has a wing and if the exterior of the cone is smooth then it is an Agathis. Its winged seeds spin as they fall—dropping like a helicopter approaching its landing pad. If the ovule is embedded into the scale, if the seeds are not winged and if the leaves are sharply pointed then the tree is an Araucaria.

In the cone which Jones took to Ken Hill the seed was free from the scales, winged all around and the cone was spiny like a little round pineapple. As Hill described, the seed-cones of this startling new genus had the external appearance of an Araucaria, such as the bunya pine, and the internal structure especially in its sexual organs of an Agathis such as New Zealand’s kauri pine. Jones and Allen were calling it a Wollemi pine but now the genus needed a scientific name.

Soon after its formal identification Wyn Jones suggested the tree’s formal names should commemorate the Wollemi wilderness. Allen told him that it would have to be Wollemia because in botany the genus is always a noun of the feminine gender. Both also wanted to honour Dave Noble so they decided to add the Latin noun form noblei. Naming the tree, however, turned into the beginning of a bitter dispute between Allen and Jones on the one hand and Ken Hill on the other. Hill, who did play a crucial role in giving scientific rigour to the taxonomic description of the new genus, was frustrated that he had been excluded from the early identification process. Allen and Jones felt that they had done all the hard detective work and therefore decisions about naming the species should be made by them. Hill was backed by the full weight of two government bureaucracies, Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens and the National Parks and Wildlife Service. Allen and Jones, although both associated with government agencies, were discovering that the days of the tree being theirs alone were numbered.

Hill, together with his colleagues and superiors at the Royal Botanic Gardens, insisted on changing the species name to nobilis, the Latin adjective meaning ‘noble’. Noblei, they feared, would be bastardised to ‘nobbly’. A tense vote was held between Allen, Jones and Hill. Allen voted for noblei, determined to see Dave Noble honoured. Jones voted with Hill as part of a deal ensuring that Jan Allen would be allowed to be a joint author of the scientific paper announcing the discovery of the tree to the academic world. Thus the new genus became Wollemia nobilis by two votes to one.

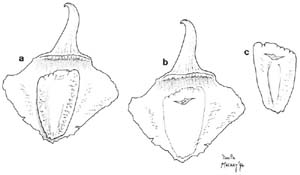

Cut open a Wollemia seed-cone and this is what you will see. On the left (a) the curly tail at the top of the seed-scale complex sticks out of the cone and gives it a prickly appearance. The seed itself is the fingernail-shaped object sitting on the scale. The drawing in the middle (b) shows the scale with the seed detached. And to the right (c) is the seed itself which has a papery wing all around it.

I first began to hear rumours that a weird species of fern had been found in September 1994, just days after Noble brought back the first fragment of foliage from the canyon. Such occurrences are fairly common in Australia and I didn’t think too much more of it, though I asked contacts in the National Parks and Wildlife Service to keep me informed. I began to hear gossip through November that something big had been discovered but was unable to find out what. On Sunday 11 December its full magnitude was revealed to me by NPWS staff, who invited me to travel to the Blue Mountains the next day to meet Jones, Noble and Allen. Everybody was very nervous about how the new genus would be publicised. Jones especially was concerned about the ramifications of the story being published at this point. But by this time—and I did not yet know of all the machinations that were taking place—the management of the tree was being wrested out of his control. At first Jones did not even want to show me material from the Wollemi pines. He later returned home and collected a bag of foliage hidden there. It was so fresh that the plastic bag was full of condensation. We agreed that I would write a story which the Sydney Morning Herald would not publish until Wednesday 14 December.

On the eve of publication, I went and met Ken Hill for the first time. He had not yet seen the Wollemi pines in the wild. That afternoon I asked him whether it was possible for me to see any of the fossils to which the living Wollemi pines were related. He had none in his office but together we walked across town, through Hyde Park, the green heart of Sydney, across William Street and into the bowels of the Australian Museum. There a 150-million-year-old fossil from an ancient monkey puzzle called Agathis jurassica was produced, which to an untrained eye was identical to the green Wollemi pine frond that Hill had brought with him from his office. This particular fossil specimen had, as it happened, been named and described by Mary White. The Herald photographer Peter Rae asked me to hold the flash as Hill posed with the fossil and the frond.

I returned to my office and, for the first time, fully briefed my editors about this incredible story. My immediate boss at the time was Bob Beale, one of the finest and most respected science correspondents in the country. Beale spoke to his superiors and in turn impressed upon them how significant this discovery was. I then sat down to write, and I remember clearly the sensation that I would not be able to do the story justice. After I had prepared a draft, Beale and I sat together and produced our finished copy. It was nearly dark when I left the office. I can still feel the sense of excitement that comes along only a few times in a journalist’s career when you know, as you head home to bed, that the presses are churning out a story which everyone in your city will either read or hear about when they wake up.

By Wednesday morning that photograph of Ken Hill had been digitised and wired around the planet. Stories about the Wollemi pine ran everywhere from the New York Times to the International Herald Tribune, from Japan’s Yomiuri Shimbun to the Daily Telegraph in London. A few months later when I was on exchange with an Indian newspaper the two things that my Indian colleagues most wanted to talk about were Australian cricket star Shane Warne and the ‘pinosaur’.

Within days all the researchers whose names had been mentioned in the various stories that were published around the world found themselves being swamped with requests from people who wanted either to see or obtain the tree. A letter from an American claimed that he had already begun to construct a special conservatory in which to grow a Wollemi pine: ‘A dawn redwood (about twenty-five feet) is thriving in my backyard. And I lust for the Wollemi pine, both to see it and to grow it.’ From a father in Japan, apologetic about his English: ‘I found a report of a newspaper which a new kind of pine trees had discovered in Australia, and the pine trees are thought that had extincted in the time when the dinosaurs had still lived. And at your botanical park, the buds come out.’

Unsubstantiated rumours immediately began circulating that one conifer collector had offered $500,000 for a Wollemi pine. These rumours would persist over the next few years. At the end of 1999 Ken Hill was at a conifer conference in the UK when he was told that a group of avid German collectors had discovered the location of the pines and was preparing a raid. Extra checks on the grove were ordered by the management team.

On the weekend after the story had broken I dreamed that a scorching forest fire had broken out in the canyon and that I was standing among smouldering charcoal remains—all that was left of the Wollemi pines. It was not such a ridiculous dream. Wollemi is a place where sometimes the best technique for fighting fires is to let them burn for weeks until they run out of fuel.

Only a couple of months after the pines had been discovered a massive blaze broke out in the park. A Wollemi wilderness fire is almost impossible to tackle on equal terms—usually the best firefighters can hope for is to contain the conflagration within the boundaries of the park.

At the time, the National Parks and Wildlife Service was employing a new technique to fight fires called bird-dogging. The name was borrowed from the nickname given to troops in choppers in Vietnam, whose job was to guide bomber pilots to their targets. David Crust, who in the next five years would spend more time with the pines than probably any other person, was the first ranger in New South Wales to be put through bird-dogger training. Instead of guiding napalm runs his task was to direct converted crop-dusters—called air tractors—to the exact location for a water drop. As a birddogger, Crust does not fly the helicopter but sits beside the pilot and controls all communications.

I went along to watch him at work. Sitting in the backseat of a chartered helicopter above the gorges of Wollemi—three choppers in total had been called in to fight the fire—we could see a wall of flame moving through the forest in a front a kilometre long. On the ground were teams of NPWS staff, ant-like from the air and armed with rakehoes. These firefighters had been dropped in by choppers. The Sydney Morning Herald photographer with me, Bob Pearce, was hoping to capture one of the air tractors on film as it dumped several tonnes of water on the inferno below. Over the radio Crusty asked the pilot to do a practice run so the photographer would have an idea of where the plane would fly.

The air-tractor pilot’s voice crackled over the radio agreeing to the request. Soon we could see his aircraft swing towards us, at first a mere dot against the smoke, then a beast bearing down towards our helicopter, which was still hovering above the fire-front. At the last second the air-tractor pilot remembered that as this was a practice run he had not offloaded his cargo of water and would be struggling to gain the height necessary to get above the gorge wall behind the fire. His plane and our helicopter were on a collision course because of the miscalculation. Our pilot had no choice but to put the chopper into free fall. It plummeted about a hundred metres, leaving our insides in the clouds and the photographer’s gear almost plastered to the roof. By a minor miracle the plane missed and the chopper pilot brought his strained aircraft under control. Crusty turned around from the front seat and said, with a strange smile, ‘Sorry’ bout that, guys.’

The final, formal act in the discovery of Wollemia nobilis was announcing its presence to the scientific world. ‘A stand of large trees has recently been discovered in a remote part of the Wollemi wilderness,’ begins the paper that was submitted on the day before Christmas and accepted in March 1995 for publication in the scientific journal Telopea under the authorship of Jones, Hill and Allen.

‘Distinguishing characters of Wollemia not shared with either Araucaria or Agathis,’ they declared, ‘are the spongy, nodular bark that sheds its outer surface in thin papery scales, and the terminal placement of male and female strobili on first-order branches…The generic epithet recalls the Wollemi National Park, where this plant was found…The specific epithet honours David Noble of the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service, a contemporary explorer of the remote parts of the Blue Mountains, who first discovered this plant.’

Genetically and in evolutionary terms the Wollemi pine appears to sit somewhere between the two genera known to exist prior to its discovery. ‘I would have expected Wollemia to have been fairly widespread,’ Ken Hill told me during a visit to the gardens. ‘The Araucariaceae were fairly widespread and I wouldn’t be entirely surprised if Wollemi pines were once in the northern hemisphere.’ The family has travelled far across two of the greatest barriers that the earth imposes on life—time and distance—and yet a Wollemi pine and some other members of the family still look like the ferns from which they evolved. ‘The Wollemi pine is 300 million years from a fern,’ Hill said. ‘It’s a very different thing from a fern. Wollemia is a conifer, it is a seed plant and all the evidence we have is that the seed plants, including the conifers and flowering plants, came from a single ancestor. Wollemi is closer to the dandelions than it is to the fern. They have both come from a common ancestor more recently than ferns have been related to them.’

The find meant that, while New Caledonia has the world’s most diverse collection of monkey puzzles, with five species of Agathis and thirteen species of Araucaria, Australia is the only place with all three genera—Agathis, Araucaria and Wollemia.

There was now a series of urgent questions that needed to be answered about the Wollemi pine. The first question of all was simple: how had such a big tree stayed hidden?

Had anyone come close to finding them before David Noble?

Wyn Jones has gone to extensive lengths to determine whether the Wollemi pine is recorded in local Aboriginal stories and has found absolutely no hint of this. The seeds of monkey puzzle trees like the bunya pine and the hoop pine have been documented as food sources for Aborigines living in Queensland. Trees notched to help Aboriginal climbers can still be seen in the Bunya Mountains National Park. Each bunya pine was the responsibility and property of a particular man—a right passed from father to son. Considering the detailed understanding Aboriginal people have of their country, it is hard to believe that if the Wollemi pine had been known by a tribe that its presence would not have become important. It is possible that there were so few trees and which proved so difficult to access that the Aborigines had no use for them.

There were at least two previous occasions when researchers almost stumbled on the trees. In autumn 1984 Jones was helping Alex Floyd, one of Australia’s great rainforest botanists, with a survey in Wollemi. Jones and Floyd did ten days of field work in the wilderness. They flew down the canyons in helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft and went along a tributary of the creek where the pines were eventually found. They got within 200 metres downstream of Wollemia.

Even earlier, in 1982, senior ecologist at the Royal Botanic Gardens, John Benson, was hiking in the wilderness and missed finding the trees by a few hundred metres. These two parties of respected botanists, within two years of each other, had come to within half a kilometre of the pine, proving just how remarkable it was that a scientifically unqualified bushwalker ended up making the botanical find of the century.

Benson was, nonetheless, one of the first humans to see the Wollemi pines—a week after the public announcement he was taken to the grove. He, like Jones, first saw them silhouetted against the sky. ‘It was like an alien had landed on earth because it was totally out of place with the vegetation of that area,’ Benson told me after his visit. ‘Of course it looked different from the eucalypt forest, but it also looked different from the rainforest because of the structure of the trees, the shape of the leaves, the bark—everything,’ He said the pines gave the impression of sheltering in that canyon as if they had travelled from far away to escape. ‘I have to think of the ents in The Lord of the Rings—the trees that fought alongside the hobbits and when they got really motivated they had the capacity to pull up their roots and move. These trees,’ he concluded, ‘retreated to an ever smaller niche as Australia dried out.’

Benson was also strangely reminded of the plastic Christmas trees that many families keep in dusty boxes in the top cupboard. Each year the box is pulled out, a tall straight trunk is slotted into a base and then in just a few seconds the branches are clicked into place. It was the simplicity of the pine’s architecture that was so striking.

One of the key officials involved in easing the strained relations between Jones, Allen and Hill was Carrick Chambers, director of the Royal Botanic Gardens. In the first few months of 1995 a memorandum of understanding was signed between the National Parks and Wildlife Service and the Royal Botanic Gardens that divided up responsibilities for the pine and addressed the sensitive subject of how any profits from propagation would be split.

Chambers, an eminent botanist, also became preoccupied in retrieving the results of a study undertaken in the mid-1980s, when he had found Araucariaceae vegetation new to science among 120-million-year-old fossils from Koonwarra in eastern Victoria. The Koonwarra site is truly remarkable— it is thought to have been a small basin beside a larger lake all those millions of years ago—because an entire ecosystem was preserved there, in effect snap-frozen, including uncountable numbers of fish suspected to have died en masse as they were starved of oxygen. Even more startling is the fact that this ecosystem was thriving near the South Pole—the Australian continent had not yet moved north to its present location. Some scientists believe that at that time Madagascar and India were still joined to Antarctica as was Australia. It would have been possible—if perilous given the wildlife—to walk from the South Pole to well beyond the equator. Winter darkness clamped down on this swampy and hostile landscape for months on end: the aurora australis, or southern lights, and the stars may have been the only illumination. In the forests the vegetation was spaced apart to take advantage of these low-light conditions.

Normally where plant fossils are discovered there are no animal remains and vice versa. This is because acid levels in the sediment that preserve plant material are higher than those that preserve animals. But at Koonwarra flea fossils are bountiful, indicating the presence of mammals, and cicadas that look the same as those that disturb the peace today were fossilised. Cockroaches rustled through this landscape, too, and flies, mosquitoes and spiders appear in the stone as though swatted only a few moments earlier. Such richness suggests that in these stultifyingly humid but cool conditions invertebrates would have made life a misery. A small collection of very precious and rare feathers were also found although no-one knows whether these were from a true bird or from one of their ancestors—a dinosaur. From other locations nearby, of a similar age, scientists have learned that this environment hosted swarms of dinosaurs of every variety: carnosaurs, kangaroo-sized Leaellynasaura with specially adapted eyes to cope with winter darkness, pterosaurs flying above the canopy and lurching relatives of stegosaurs. This world was a violent one, and a small fossilised Leaellynasaura was found, suffering from a chronic bone infection in one of its tibia. It may have received the infection after being attacked; the fossil evidence indicates that the animal lived for up to five years after its immune system began to fight the disease. Other placental mammals—creatures the size of marsupial mice—lived in this unforgiving environment. Among the dinosaur remains found in this area were lower jaws with dentition that indicates the animal may be an ancestor of the northern hemisphere’s hedgehog.

Many types of plants were preserved with the notable absence of flowering plants, which means that the deposits were laid down either before flowers had evolved or before they had reached that part of the prehistoric world. Koonwarra 120 million years ago was a forest dominated by ginkgoes—a tree represented today by a single species first seen by western botanists in China in the eighteenth century. Leaves from Koonwarra’s ginkgoes fell in huge autumnal beds and these too have been preserved.

Chambers and his colleague Andrew Drinnan published the results of their discoveries at Koonwarra including drawings and photographs of the material. They did not, however, ascribe a scientific name to the fossilised plant they had found but they clearly stated it belonged to the family Araucariaceae. Almost as soon as he learned of the discovery of the Wollemi pine, Chambers became intrigued by the possibility that it and his mystery plant were one and the same thing. The foliage that Jones had brought into the gardens looked like the fossilised vegetation Chambers and Drinnan had collected. In early 1995 Drinnan was working in Melbourne so Chambers flew down from Sydney with some Wollemi pine material. At Drinnan’s laboratory Chambers asked him to bring out the extra fossils they found in Koonwarra. The match was so exact that Drinnan exclaimed, ‘Jesus, Carrick, our drawings were upside down.’ What they had done was draw the ovule attached to the wrong end of the segment.

‘If Andrew and I, when we discovered the fossils,’ Chambers told me, ‘had said that one day the fossil may well be found alive we would have been drummed out of science.’

There could no longer be any doubt of the truth of Chambers’ remark on the significance of the discovery. ‘This is,’ he said, ‘the equivalent of finding a small dinosaur alive on earth.’