Need it even be said?

The question as such, the very posing of this question, of any question whatsoever, already attests to it, as does also the very possibility of need, to say nothing of the need to say or the need that it be said.

Is it not, then, indisputable from the moment any question about it is asked, indeed even before the posing of the question, obviating, it seems, the need even to pose the question, bringing everything to a halt with the mere question of need? Or even just with a display—unquestionable—of need?

The question of finitude cannot, then, simply be posed. In this entanglement it is not possible to evade the question of the question. It will always be a question of what preceded the question, of an attestation that will already have taken place—that cannot but have taken place-when the question comes to be posed.

These entanglements, though hardly unique to this question, are, in this case, highly conspicuous and obtrusive.

Questioning does not, then, begin with the posing of the question. Rather, it begins with open receptiveness to the anterior attestation and with patient, veracious response to what it displays. This double, virtually silent affirmation, saying yes twice to oneself and, above all, to what is attested, clears the site of questioning. This clearing may require only the briefest interval; or its spread may be protracted, may seem almost as if it were endless, were it not indeed an attestation of finitude.

If what is attested, what is displayed in and through the attestation, is minimally articulated, then the words will be: finitude—human finitude—that humans are finite.

This articulation gives space to the question, to a posing of the question, even if it still lacks a well-defined direction, even if it cannot but continue to grope for the appropriate words.

What is displayed in the attestation of finitude? As what is finitude disclosed in and through this attestation? Or simply, responding now more directly to the attestation: What is finitude?—assuming, at least as a beginning, that it has a what, that it can be appropriately interrogated by asking about its whatness, that it accommodates itself to this question.

And yet, initially the sense of finitude or the finite seems to depend primarily, not on its whatness, but rather on a specific opposition. Or if, in this connection, the question of whatness is to be retained, then it will be asked: What is the finite other than the opposite of the infinite? Is it not precisely as the opposite of the infinite that it is determined as such? Since opposition is not necessarily symmetrical, since there can be an order of priority between the two terms opposed, the question mutates into one of priority: Is it that each—the finite and the infinite—is simply what the other is not? Or is there a formal priority of one over the other? If consideration is limited to the mere formation of the words, the addition of the purely privative prefix to the root, then a formal priority can be accorded to the finite. Yet, semantically considered, the order appears to be precisely the reverse. Finitus is the past participle of finere: to limit, bound. Hence, the finite would result, constitutively, from the imposition of a limit or bound on something otherwise unlimited, unbounded. Thus, the finite would presuppose the infinite, and priority would need to be accorded to the infinite.

The instability in the opposition considered at this level is indicative of the need to pose the question in a less formal, more rigorous manner. Each term needs to be reoriented to that to which it primarily pertains, or at least to that in relation to which its theoretical determination has been carried out.

The question of the finite is thus brought back to the initial, minimal articulation. In the question it is preeminently the human that is in question, the human as such. Determining the human as finite has nothing to do with the incapacity to perform this or that deed but is rather a strategy for thinking the human as such, for delimiting human being in its very propriety.

Though brought to bear on the idea of the transcendent in ways that are substantial and consequential, the original locus of the concept of the infinite—at least as rigorously developed—is that of number. Even within the framework of Greek mathematics, in which number (ἀριθμóς) refers to a number of things, which can be counted (ἀριθμέω), even at the level where these countables are not actual things but ideal units, the unlimited extent of number is fully recognized: especially if the countables are ideal units, it is always possible to count further. The series of numbers is unlimited, endless (ἄπειρος), without (α-privative) limit (πέρας), infinite. And yet, the mathematical concept of the infinite has proven not so stable, so secure, as had been assumed since antiquity. Modern developments in mathematics have shown that it does not suffice to refer simply to infinity (with its single symbol ∞) as if there were only one kind of infinity, as if infinity—the kinds or degrees of infinity—could not be manifold.

There are many ways in which the concept of infinity has been extended beyond the domain of number and thus brought to bear on a substantial content. Though these ways are sufficiently diverse that they resist being gathered under a common rubric, the dominant orientation is to the transcendent, to the determination of the divine in its Christian-theological form. The extension may be carried out by way of transition from finite to infinite, from experienced, finite characters or attributes to those same attributes in unlimited, infinite form. The result is a doctrine of the divine attributes: God is infinitely good, infinitely true, etc., and the pertinent question is whether and how humans in their finitude are capable of comprehending the infinity of the divine.

The critical philosophy takes a different path, although, except for its skeptical moment, the result is not so very different. In the Critique of Pure Reason the concept of God is determined transcendentally as the ideal completely determined by the idea of the totality of all positive predicates (realities).1 From this transcendental ideal the attributes of the infinite can be derived (ens originarium, ens summum, ens entium, ens realissimum), though within this critical, theoretical context the question of the existence of such a being remains undecidable.

And yet, to Kant’s successors it became evident that the positing of the opposition between finite and infinite—perhaps even as in the first Critique, but most definitely as required by the developments broached by the other two Critiques and furthered in German Idealism—can only have the effect of finitizing the allegedly infinite. Hegel makes this effect explicit when he writes in the Science of Logic: “If the infinite is kept pure and aloof from the finite, it is only finitized.”2 A passage in the Encyclopedia explains: “Here infinity is set firmly over against [fest gegenüberstellt] finitude, yet it is easy to see that if the two are set over against one another, then infinity, which is nevertheless supposed to be the whole, appears as one side only and is limited by the finite.—But a limited infinity is itself only something finite.”3 What is thus required, according to Hegel, is the speculative move by which the simple opposition between the finite and the infinite would be cancelled and surpassed as such—in a word, aufgehoben. What is required is that the infinite not be merely opposed to the finite but that it contain the finite within itself. In Hegel’s words: “the truly infinite is not merely a realm beyond the finite, but rather it contains the finite sublated within itself.”4 In another passage he describes this containment as a matter of the infinite’s being—or coming to be—with itself in its other, its finding itself in its other. This true concept of the infinite—or concept of the true (or truly) infinite—he contrasts with what he calls the bad infinite, that which consists in endless progression: “But this endless progression [Progress ins Unendliche] is not the truly infinite, which consists rather in being with itself [bei sich selbst] in its other, or, expressed as a process, in coming to itself in its other. It is of great importance to grasp adequately the concept of true infinity, and not just to stop at the bad infinity of the endless progression [bei der schlechten Unendlichkeit des unendlichen Progresses].”5

If the task that now imposes itself—and there is perhaps no saying definitively how this imperative originates—is to forbear the sublated opposition without regressing to mere endlessness, then it is necessary to frame a third concept, one that resists even being designated as a concept in the strictest sense. It may appear that at least in the area of cosmology the concept of infinity as endless progression must, even if in disguise, remain operative, as ever more powerful and refined telescopes reveal ever more remote galaxies; yet even in this area, as further analysis will show, there are profound mutations that have the effect of dislodging the merely linear representation. Furthermore, this representation depicts the infinite as entirely disconnected from the self-showing by which the human, precisely as finite, is engaged; there is no single endless progression that shows itself as such. If this representation is to be transformed and the concept of infinity appropriately redetermined, then the manner in which infinity becomes manifest must be accorded a decisive role.

To be sure, modern mathematics has succeeded in determining the concept of infinity with rigor and precision (though not without significant and, it seems, unavoidable lacunae). Yet this determination cannot be directly taken over but must, rather, be submitted to the protocol governing such transition. The result will contribute significantly to the preparation of a third concept of infinity. In turn, the relation between the infinite and the finite can be shown to be other than one of mere opposition, and in this way the concept of finitude, too, can be redetermined.

The framing of this third concept must, then, steer a path between—and in a sense beyond—the determination of the infinite, on the one side, as endless progression and, on the other side, as the overarching concept that sublates the finite within itself, that passes through the finite in such a way that it draws the finite back into itself as itself. The itinerary must lie between the linear representation of infinity and its representation as a line that turns back upon itself to form a circle—or even, since the circling is reiterated, taking, as Hegel says, the shape of a circle of circles. Even though, because it is the figure operative in modern mathematics, the linear representation alone will be addressed at the outset, the analysis will eventually circle around to the Hegelian alternative. The definitive figure that, in this connection, will take shape will be neither a line nor a circle but rather a figure that combines—and transforms—these two. Yet even this figure, the spiral, is only a geometrical representation merely indicating, across the span joining and separating mathematics and philosophy, the originary determination that must be brought to bear on the sense of infinity.

The development through which modern mathematics has determined and investigated the concept of infinity has significant philosophical implications that cannot simply be passed over. Prior to this development it was assumed that there was only one infinity—only one type of infinity—without any further differentiation. This assumption was shared by mathematicians and philosophers, and it went almost entirely uninterrogated, even when, on the side of philosophers, the task of determining that which is allegedly infinite (the world as a whole, God, etc.) was strenuously undertaken. This situation is exemplified, in an aporetic context, by the Kantian antinomies. Even Hegel, in formulating his speculative concept of infinity, proceeded by opposing it to the single, common mathematical concept of infinity as an endless progression, exemplified, for example, by the series of natural numbers (positive integers).

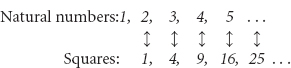

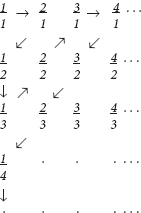

But already with Galileo a development began that eventually would overturn this common assumption. What Galileo discovered was a peculiar equivalence: that, in his words, “the multitude of squares is not less than that of all numbers, nor is the latter greater than the former.”6 Though he does not offer further information as to how he came to this conclusion, one can surmise that what he grasped was the possibility of establishing a one-to-one correspondence between the series of natural numbers and the series of squares of those numbers. The correspondence would take the following form:

Since both series are infinite, there could be no point at which either series would lack a further number to correspond with a number in the other series. Thus, it turns out that the set of natural numbers is equal in number to the set of all squares of these numbers, even though the set of squares is a subset of the set of natural numbers. Galileo’s conclusion was that “the attributes of equal, greater, and less have no place in infinite, but only in bounded quantities.”7

The next step in this development was carried out by Bolzano and Dedekind. In effect, they took the property of infinite sets that Galileo had discovered, that such a set can be put into a one-to-one correspondence with a part of itself, and made this the very definition of an infinite set.8 Furthermore, Bolzano proved that this property holds for the dense numbers of the continuum (dense defined to mean that between any two distinct numbers there exists another number).9 The proof is based on the simple function y = 2x, by means of which a one-to-one correspondence can be set up between the numbers in the interval 0 to 1 and in the interval 0 to 2.

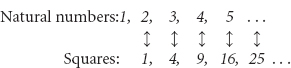

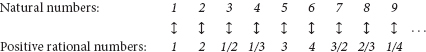

The most decisive stage in this development came in the work of Georg Cantor (beginning in the 1870s). Two conclusions that Cantor established were of unprecedented significance. Both had to do with whether certain sets of numbers are denumerable; a denumerable set is one that can be put into one-to-one correspondence with the set of natural numbers. The first of Cantor’s conclusions was that the set of all rational numbers (numbers expressible as fractions) is denumerable. In order to prove this, he used an ingenious method of diagonalization to set up a one-to-one correspondence between the set of natural numbers and the set of positive rational numbers.10 In this case it turns out again that the cardinal number of a subset (the natural numbers) is the same as that of the set to which it belongs (the positive rational numbers). Such numbers Cantor called transfinite numbers.

The question that arises is whether there is only one transfinite number, that is, whether all infinite sets are denumerable. Cantor’s answer to this question was the second of his major discoveries. His conclusion, that there are sets that are nondenumerable, altered once and for all the way in which infinity must be conceived.

Specifically, what Cantor proved was that the set of real numbers is nondenumerable. The real numbers include algebraic numbers (roots of polynomial equations with rational coefficients), which, in turn, include all rational numbers; and those that are not algebraic, which are called transcendental numbers. In other words the set of real numbers includes all numbers that can be expressed by an endlessly repeating or nonrepeating decimal. Cantor’s proof is limited to the real numbers in the interval 0 < x < 1, but since a one-to-one correspondence can be established between this interval and any other, the conclusion he draws is completely general. Here again Cantor employs a diagonal process in order to construct his proof.11

It follows that the transfinite number of the set of real numbers is greater than that of the set of natural numbers and greater than that of the set of rational numbers. Thus, not all infinities are equal; rather, there are at least two orders of infinity, two transfinite numbers. Cantor designated these by the Hebrew letter aleph: ![]() 0,

0, ![]() 1.

1.

The question that immediately arises concerns the difference between these orders: What, other than denumerability, distinguishes one order from the other? What, in other words, is the character of the ordering? What is the difference between the two infinities? In this connection Cantor established a result that even he found surprising and that—as with so much that concerns infinity—runs contrary both to common sense and to suppositions that seemed self-evident even to the mathematicians of the time. What Cantor proved was that the points on a square can be put in one-to-one correspondence with points on a line. To construct his proof, he began with the representation, in Cartesian geometry, of each point on a square by means of two coordinates. Taking a line segment from 0 to 1 and a square with sides consisting of line segments on the same interval (possible without loss of generality), he devised a method by which to transform each pair of coordinates into a single number (thus representing a point on the line).12 Cantor concluded that there are as many points on the line as on the plane. Using a similar method, he proved that the number of points on the line is the same as the number of points in a three-dimensional space, and likewise for a four-dimensional space and indeed for a space of any number of dimensions. In other words, the transfinite number of the continuum (= the number of points on the line = the number of the set of real numbers = ![]() 1) is the same as that of the plane and of any n-dimensional space. In all these cases the set is nondenumerable. More specifically, all have the same transfinite number. Therefore, it follows that the ordering of infinities has nothing to do with dimensions.

1) is the same as that of the plane and of any n-dimensional space. In all these cases the set is nondenumerable. More specifically, all have the same transfinite number. Therefore, it follows that the ordering of infinities has nothing to do with dimensions.

Yet establishing a positive ordering principle, even establishing the ordering itself of the various infinities, has proven much more difficult. Cantor was able to determine one other order of infinity greater than the first two (those of the natural numbers and of the real numbers): this was the infinity of all functions (continuous and discontinuous) defined on the real line (= the continuum). Furthermore, he succeeded in proving that for any set there is always a larger set, namely, the so-called power set, consisting of the set of all subsets of the given set. For a set of n elements, the power set consists of 2n elements. Thus Cantor could conclude that exponentiation does have a bearing on the ordering of infinite sets; hence 2![]() 0 is a greater transfinite number than

0 is a greater transfinite number than ![]() 0. And yet it has not been possible to establish the precise order of the transfinite numbers. Though it is commonly supposed that the transfinite number of the set of real numbers is the next such number after that of the set of natural numbers, no proof has been found for this ordering. Indeed it was on the attempt to prove this so-called continuum hypothesis that Cantor labored so intensely and so long that he allegedly suffered, as a result, a mental breakdown. What has been proved, much more recently, is that the continuum hypothesis is undecidable, that it is independent of the postulates of set theory and thus cannot be deduced from these postulates.13

0. And yet it has not been possible to establish the precise order of the transfinite numbers. Though it is commonly supposed that the transfinite number of the set of real numbers is the next such number after that of the set of natural numbers, no proof has been found for this ordering. Indeed it was on the attempt to prove this so-called continuum hypothesis that Cantor labored so intensely and so long that he allegedly suffered, as a result, a mental breakdown. What has been proved, much more recently, is that the continuum hypothesis is undecidable, that it is independent of the postulates of set theory and thus cannot be deduced from these postulates.13

The order of the third transfinite number that has been determined also remains unestablished. No proof has been found that this number, that of the set of all functions, is the next transfinite number after the number of the set of real numbers.

Even though the continuum hypothesis and other questions concerning the transfinite numbers remain undecidable or at least undecided, what Cantor’s research demonstrates is that there are multiple infinities, multiple kinds of infinities, infinities that can be rigorously differentiated, infinities that are greater than other infinities.

Beginning in antiquity, there is a recurrent realization that the transition from mathematics to philosophy requires a decisive shift in the mode of thinking. The shift involves multiple factors: a transition from abstract to concrete, from quantity to quality, or from the abstractly quantitative to the concretely qualitative. If the quantitative moment involved is that of transfinite arithmetic, then, as Galileo recognized, the very sense of greater and less, that is, of quantity as such, is transformed. Furthermore, the description of the shift as a transition from the quantitative is quite insufficient. For, especially in view of modern developments (such as those dealing with algebraic structures), it is evident that the concept of quantity does not suffice to delimit the domain of mathematics; rather, a more generalized conception is required, for example, that mathematics is the science of abstract form or structure. The other term of the shift would also require generalization: it would be necessary to redetermine the qualitative so that it no longer refers to qualitative properties of things, but rather to any aspect by which something might show itself.

This shift can also be regarded as a transition from the less to the more originary or archaic, as a transition in which thinking would achieve an otherwise unattainable proximity to the origin (ἀρχή). Yet the origin from which all things come forth is self-showing, and thus the transition would be effected by reference to the self-showing through which aspects—aspects of things, but also other kinds of aspects, aspects of other kinds, even aspects of what neither is nor belongs to a kind—come to show themselves concretely.

To a degree it can be maintained that mathematics, too, refers to self-showing and proceeds precisely on this basis. For in mathematical proofs the sequence of steps requires that one apprehend the connections that become evident and that at the end of the proof one have insight into the result that has come to be shown through the proof. And yet, the result stands apart from the showing that the proof effects rather than emerging directly in, as well as through, the showing. In this sense the proof does not belong to the result itself but rather, once the result has been reached, is over and has disappeared and, as far as the result is concerned, can be discarded. Hegel points out that in the proof of the Pythagorean theorem concerning the relation between the sides of a right triangle, the triangle itself is taken apart, and each part is related to another figure constructed on it, namely, in each case a square with sides equal to the side of the triangle. Only at the end is the triangle restored; from the result that has then been shown about it, the various constructions and the proof based on them can be detached, and indeed in the theorem itself they can be left behind, allowed to disappear.14 On the other hand, what the transition to philosophy requires is that the externality of the showing be eliminated so that the showing adheres to the result, so that what shows itself emerges directly in and from the showing.

In broaching this transition, it needs, then, to be asked: How does infinity show itself concretely? What is it that shows itself concretely as infinite? To suppose that it is endless progression would be to ignore both Hegel’s incisive critique and the sense of what the transition to philosophy requires. An endless progression cannot show itself concretely as such but can be apprehended only abstractly, only mathematically. What shows itself concretely as infinite is, rather, whatever surpasses us immeasurably, whatever exceeds us indefinitely, without limit, as does, perhaps most manifestly, the diurnal sky. It is the ἄπειρον, considered in its bearing on the configuration of self-showing.

Human finitude is, then, to be determined as being indefinitely exceeded. The exceeding that is most manifest, most open to view, is that of the elementals in nature, of earth and sky, of sea, wind, rain, thunder and lightning, etc. In exceeding the human, these elements of the natural infinite are not simply aloof, not utterly beyond the human; rather, the human, precisely as it is exceeded, is bound up with them, encompassed by them, by each in its distinctive way.

In their manner of showing themselves, these elementals are quite different from things: they have no lateral horizons, and consequently they do not show themselves by holding in store and deploying one by one a wealth of further profiles so as to acquire bounds and density. Rather, these elementals show themselves as indefinitely expansive, and this expansiveness is bound up with their excessiveness. Their expanse is not the same as their extension; it does not consist in their extending endlessly. Imposition of a uniform measure could mark limits, though the expanse would retain an indeterminateness somewhat like that of the borders treated in fractal geometry, which vary with the measure of the measure. These elementals in their expansiveness are gigantic in that there is lacking all proportionality with things and with all that otherwise concerns the human;15 their gigantean disproportionality is bound up with their character as moments of the concrete, natural infinite. While belonging to nature, they are not things of nature, do not display the bounds and containment that nature imparts to things. In this sense these elementals of nature are both natural and unnatural; they surpass natural things, fall outside nature, yet do so precisely within nature, bordering therefore on contradiction. They are like creatures in which parts of different creatures are unnaturally—in a way counter to nature—combined—that is, monsters.

The elementals in—yet also counter to, outside, beyond—nature are, then, gigantic and monstrous. In indefinitely exceeding the human, they are therefore overpowering, overwhelming. It is from their expanse that the giants and monsters who are said once to have strode across the earth would have arisen. Yet it is also from this elemental expanse as it enshrouds itself that what is most enthralling can radiate and in its radiance let the gods appear. And what is the passing of the last god if not a return into self-enshrouding radiance? Or into a renewed gigantomachy?

In the pluralizing of the elemental in nature, there is already a hint at the kind of identity and differentiation that is analogous to the results of transfinite arithmetic. Just as the transfinite number of a subset can be the same as that of the set to which it belongs (as, for instance, in the relation between the natural numbers and the rational numbers), so the expanse of wind and rain can coincide with the expanse of the storm to which they belong.

The elementals in nature exceed the human indefinitely. But what is the human? What is it to be human? What is it to be—as each is—a singular being? Does the sense of these expressions accord with questions concerning whatness, with questions as to what it is, questions about its being? Does it suffice to ask: What is its relation to its being—as if in the is the very question posed were not repeated, as if the sense of the is were not necessarily assumed in the very posing of the question? Or does the question of its relation to being remain abstract? Do humans relate to their being in the same manner, at the same level of concrete self-showing, as when in the depth of the night they behold the starry heaven?

The human is centered in the proper. What is most properly human is the proper. The proper is what is one’s own; it is indeed what is one’s own in an absolutely unique, incomparable way and degree—hence one’s ownmost. Whatever else can be called one’s own is so only on the basis of this ownmost; the proper is the very condition of possibility of owning in the usual—for instance, material—sense.

The proper is not to be identified with the self: not because it is something other than the self but rather because it represents a way of thinking and saying the ownmost that is anterior to the formulation of the concept of the self. In fact, the concept of the self is of relatively recent origin.16 Even in Locke’s Essay, published in 1690, that which later will be designated by terms such as self-knowledge is repeatedly described as perception of “our own existence.”17 Though in the present endeavor there is no intention of returning to this earlier conception, there is an insistence on formulating the question of the human at a level prior to its encapsulation by the concept of self. Consistency in following up the implications of this formulation will require rigorous prescriptions regarding the semantics of certain common words in which the expression, if not the concept, of self has insinuated itself.18

The proper is the ownmost. What is ownmost is that into which nothing other than one’s own intrudes. It is that in which one is related only to one’s own, that in which one owns (as in owning up to a deed) what is one’s ownmost. Yet, what is decisive in this owning is that it is not such as to produce or enclose an interiority. It is not a circuit of self-consciousness that, constituting an interior space as such, would then be fulfilled through assimilation to this space; on the contrary, the proper is constitutively prior to the concept of consciousness, no less so than to the concept of the self. In its owning, indeed as its owning, the proper does not turn back enclosedly upon itself but rather opens the ownmost to the other in such a way that reflection from the other is possible without appropriation, reflection in which the proper of the other remains intact. The owning of the proper is also an opening out to the elemental, an opening in which the proper is given back to itself disclosedly.

Such return from engagement with the elemental in nature constitutes a reversion. As, in one direction, each elemental indefinitely exceeds the properly human, there occurs, in the opposite direction, a recoil back upon the human; thereby one is disclosed to oneself as enfolded, encompassed, by the elemental. In this self-disclosure it becomes manifest that one is continually reliant on the elements, most openly on the sky and much that comes from it, but also on the earth and its bounty. But equally it becomes manifest that one is exposed to the gigantic excess of the elements, as to the fury of a storm with its “tempestuous noise of thunder and lightning.”

This bidirectional relatedness to the elemental as natural infinity both belongs to the proper and transgresses the propriety of the human. It constitutes a moment of human finitude, which manifestly is no mere symmetrical opposite of infinity. In its bearing on the proper, this double relatedness turns the proper, in a sense, against itself; for in transgressing the limit of the proper, it installs impropriety within the proper, deforms it, as it were, into a propriety to which expropriation integrally belongs, an expropriation operative within the proper. In rupturing the sphere of ownness, this relatedness both robs one of ownness and yet belongs to the very constitution of one’s ownness, restores it. Because it is in relation to the natural elemental that the proper is thus shaped (in its misshapenness), this elemental can also be appropriately termed a proper elemental.

The expropriating relatedness to the natural elementals is perhaps most purely attested on those rare occasions when deliberate observation of nature is arrested in order to let natural elementals become completely engaging. One lets one’s vision be filled entirely by the sight of a towering mountain peak. One lets nearly all one’s senses be entranced by the sight, sound, waft, and coolness of the sea stretching to the horizon. On such occasions the engagement is not in discovery, measure, form, or essence. There is no intent to circumscribe what such elements are. It is only that one is prompted to let the senses be solicited by the elements, to abide with them, to linger there patiently and attentively. Such uncommon engagement can intensify into ecstasy: one is not only drawn beyond oneself but also restored to oneself as the elements resound in silence.

Whereas the framing of the third concept of infinity, as proposed at the outset, has, from that point, proceeded by concretizing and reorienting the concept of infinity as endless progression, the resulting determination of infinity as indefinite excess brings the exposition into a certain proximity to what Hegel designated as the concept of true infinity, in distinction from the bad infinity of endless progression. For it has been shown that the finite is not simply an opposite posited over against the infinite in such a way as to finitize the infinite. Rather, the relatedness is such that while the infinite indefinitely exceeds the finite, there is self-disclosive reversion to the finite. Just as indefinite exceeding is irreducible to mere symmetrical opposition, so reversion does not issue in containment. The finite is not sublated, is not enclosed within the infinite, not even (as with Hegel) in a way that, within the infinite, would preserve the opposition of finite to infinite. Rather, what is preserved is the distance across which the proper is expropriated, its limit transgressed. This distance of expansiveness and reversion is irreducible. It cannot be flattened out into an endlessly progressing line, into an infinity in relation to which the finite could only be entirely extrinsic. But also this distance and the bidirectional relatedness that spans it cannot be recast as a figure that would curve back upon itself so as, in its closure, to appropriate the finite to the infinite. The doubling back does not inscribe a circle enclosing the finite and reducing the opposition between it and the infinite to an opposition within the infinite. There is, rather, an open circulation that leaves both finite and infinite intact. In this connection the spacing consists in the circulation between finite and infinite by way of excess or expansiveness, on the one side, and self-disclosive encompassment, on the other. As a circulating determined by two points, this spacing has as its schema an ellipse, the two foci marking the finite and the infinite. Since the excess of the infinite is indefinite, the ellipse has no precisely determinable border (so that here again a reference to fractal geometry would be appropriate). In the same measure, as a circulation the repetition of which can concretize still further the excess of the elemental and further enhance the self-disclosure through reversion, the circling is opened up, and the ellipse mutates into a spiral.

Considered more concretely, the spacing governed by this schema is such as to prevent the assimilation of the properly human to the natural elementals. Since the elementals, especially earth and sky, delimit the region of nature itself (such is their monstrosity), the persistence of circulation between finite and infinite rules out any closure by which the properly human would be appropriated to the space of nature and, within that space, within nature itself, simply retained in opposition to the natural things, in an opposition that would have been sublated and hence enclosed by the elemental space of nature. No matter how inseparably the human may be bound to the natural elementals and thus to nature itself, the human in its propriety remains irreducible to the natural.

The concept of the infinite as the indefinitely exceeding breaks both with the abstractness of the concept of endless progression and with the closure of the speculative concept. Thus, it resists, evades, the very concept (or concepts) of concept: it passes between (and thus beyond) the static, abstract concept (of concept), on the one side, and the mobile, absolute concept (of concept), on the other. Because it is concrete yet open, because it is irreducible to the figure both of a line and of a circle, forming, instead, schematically, a focal point of an ellipse (which, together with the finite, mutates into a spiral), it functions otherwise than both the common and the speculative concept. It can, accordingly, be termed a protoconcept. This designation is also meant to affirm that, as further analysis will show, it is imagination—and not a faculty of concepts, not what has been called reason (among the many names)—that sustains it within its configuration.

Mathematically there are, as Cantor demonstrated, multiple infinities, different orders of infinity, as in the differentiation, in terms of denumerability, between the transfinite number of the natural numbers and that of the real numbers. The question is whether and how this pluralizing of mathematical infinity has a bearing on the philosophical protoconcept. If this result is to be taken over—in accord with what this transition requires—then it should be possible to identify multiple concrete infinities. On the basis of their differentiation, it should be possible then to identify the corresponding moments of human finitude.

The transition from mathematical to philosophical infinity requires enhanced proximity to self-showing, proximity not only in the sense that thinking must become more archaic but also in the sense that the aspect that comes to show itself must remain adherent to the self-showing itself. This connection must remain direct and enduring, unlike the relation between a mathematical proof and the result that is thereby deduced but that, as result, detaches itself from the proof. Thus, in philosophical purview, infinity is redetermined as what exceeds indefinitely the primary site of self-showing, that is, the proper. In this regard it is of prime significance that precisely in indefinitely exceeding this site, the infinite remains adjunctive to it; whatever exceeds cannot but remain also related to that which it exceeds. In redetermining the infinite as that which indefinitely exceeds the proper, a transition is also carried out from the abstractness of the mathematical concept of infinity to the concreteness of the protoconcept. Furthermore, there is effected a shift from quantity to quality, or rather, in more suitable and timely terms, from the abstractly formal concept of infinity to the concrete aspect in and as which infinity shows itself.

In order, beyond this differentiation and transition, to locate and articulate the domain of the question of multiple infinities, it is necessary to distinguish between the various ways in which proprietary self-showing can be ventured. There are two distinctively different ways in which such showing of oneself to oneself can be effectively accomplished, two kinds of showing in which one can come manifestly before oneself.

Yet both take place within a prior opening of the proper. To be sure, it has repeatedly been observed that an unmediated turn inward does not lead to the discovery of an abiding self, that in such an inward turn nothing is to be found but fleeting images. It is from such images or perceptions that, according to Hume, the very idea of the self is derived—that is, intromitted, invented—by the imagination. Hume concludes that “consequently there is no such idea”—except through “the action of the imagination,”19 which he tacitly assumes to be incapable of attesting to existence, hence nothing but sheer phantasy. Indeed for Hume the “self or person” is so thoroughly reducible to congeries of perceptions that without the latter the self ceases to exist, that is, ceases to have whatever pseudo- or phantastical existence it has. In a most remarkable passage he writes: “When my perceptions are removed for any time, as by sound sleep, so long am I insensible of myself, and may truly be said not to exist.”20 Sleep is temporary death (and in fact in the very next sentence Hume refers to death, in which all perceptions are removed). Also, it is as if, while sleeping, dreams could not have the effect of sustaining some sensibility to oneself, as if they could never appear as one’s own, as if one could never figure in one’s own dreams.

Hume compares what he calls the mind to a kind of theatre “where several perceptions successively make their appearance; pass, repass, glide away, and mingle in an infinite variety of postures and situations.” Though he warns that “the comparison of the theatre must not mislead us,”21 precisely what is misleading here is that he fails to follow through with this otherwise insightful metaphor. What he fails to observe is that a theatre is not just a place in which the actors move about but rather a site where something comes to be shown: the character and consequences of certain actions, persons, beliefs—a showing that is significant because of its bearing on the world outside the theatre.

Even if the turn to oneself does not reveal a permanent self, to which perceptions would adhere as accidents inhere in a substance, it does open a space in which the proper can become operative as such. This turn to oneself must always already have occurred, though it can also be reenacted explicitly with specifically theoretical intent. It is not a turn inward, as though the proper were an interiority shielded from things and elements. Rather, it is a gathering and setting out of one’s own, of the ownmost, the owning, that constitutes the proper.

Setting out the proper so as to impel its owning constitutes the condition, the opening, by which the two primary ways of proper self-showing can become operative. The first of these ways is by reflection, by a mode of reflection that is mediated. In this mode the mediation can be provided either by something thingly in character or by another living being, preeminently—though not exclusively—another human. There is a reflection from the other (in the inclusive sense), a reflection as in a mirror, and in the reflection of the other one catches a glimpse of oneself; one is given back disclosively to oneself, while, in that very move, releasing the other, reaffirming its otherness. From things (which, as painters attest, look back at us), from instrumental complexes (from the machine that one can operate or the musical instrument that one can play), from the eyes of an animal (which display a fidelity or a ferocity of which we, too, are capable), from others (who speak to us and to whom we can make binding promises), we are reflected back to ourselves. We are shown where we are amidst things, what mechanical or musical skills are harbored in us, our capacity for certain affective intentions, our talents for engagement with others.22 Sounds, too, especially those of music, can resonate in such a way as to be revelatory of and to us. In appropriating these reflections from things and their complexes, from animals and other humans, from sonorous figures, proprietary self-showings are accomplished. Yet in the very move in which we draw from others a reflection of ourselves, we release the other, let it withdraw into itself, let it be what it itself is.

In every case that from which one is reflected back to oneself is set within limits. Things are of limited, measurable extent and occupy a uniquely determinable place. Sounds have a limited range and duration. Living beings, too, despite their mobility, can range and extend their senses only so far, though with humans these limits border on the indeterminable, especially if account is taken of the technological supplements that extend them ever farther. Still, the encounter with other humans always takes place within a complex of limits that shape forms of association and the possibilities and range of reflections. Because, when the foreign and the foreigner appear, the domestically operative complex of limits gives way to another, there is necessarily a discontinuity that distinguishes the encounter with the foreigner, no matter how hospitable one may be, and even though interaction with the foreigner can indeed prove to be disclosive in dimensions that would otherwise remain closed off.

Yet none of the modes of reflection are in any respect oriented to infinity, not even to infinity in the concreteness expressed in the protoconcept. In no case is the span across which reflection takes place infinite in any sense; neither do the terms between which reflection occurs involve, as terms of a reflection, infinity, though in quite different connections a comportment to the infinite may be sustained. Though indeed that from which reflection is cast back to the human is set within limits, as is the human itself as a term of reflection, this limitedness does not constitute finitude; for all modes of reflection lack the bidirectional relatedness to the infinite as indefinitely exceeding the properly human. In proprietary self-showing by way of reflection, neither the infinite nor the finite has any place whatsoever. They simply do not enter into reflection at all.

Multiple concrete infinities and the corresponding moments of finitude are not, then, to be found in reflective self-showing but rather must have their locus in another—the second—form of proprietary self-showing. Whereas in reflection the proper remains entirely intact and unexposed to expropriation, whereas in this connection its domesticity is preserved as it merely opens itself, as proper, to the look, the complex, the tone, and the proper of others, the second form of proprietary self-showing proceeds by transgressing the proper and thereby compromising it, installing impropriety within the proper. In this case there is a bidirectional relatedness to the infinite, which, precisely because of its relatedness to the proper, can fittingly be termed a proper elemental. The proper is both indefinitely exceeded by the infinite as expansive and overwhelming and, in the reversion, disclosed to itself as encompassed by elemental infinity. Human finitude consists precisely in this bidirectional relatedness to the infinite. Or, more precisely, this is the form that proprietary self-showing assumes insofar as the infinite is identified as the natural elemental. For it is the elements that are expansive and overwhelming and that encompass the properly human.

What other forms of infinity can be identified—assuming that infinities have a what (answering the ancient question: τί ἐστι . . . ?), that they have form (in a sense displaceable from the classical), and that each of these forms has a determinable identity? It is abundantly evident that the differentiation between these forms of infinity that pertain elementally to the properly human cannot, as in transfinite arithmetic, rely on such concepts as denumerability (even though Cantor’s discoveries have served here as a clue indicating the possibility of multiple concrete infinities). In order to avoid regressing either to the concept of infinity as endless progression or to that of a single, absolute infinity, the focus must remain on the open concreteness of the infinite, on its determination (in a sense reoriented to the nonterminating) as indefinitely exceeding the properly human. The multiple infinities can become manifest only through the manifold aspects in which infinities show themselves as bearing transgressively on the proper.

Although proprietary self-showing from the infinite is different in kind, different in its basic structure, from self-showing that proceeds by way of reflection, there is discernible in reflection from the other human a trace of an infinite other than that of nature. The primary instance is one in which reflection from the look of the other is overrun ever so discreetly. One catches sight of another as looking back, as returning one’s glance, as taking up in reverse one’s very line of vision. One gets a glimpse of the looking in the look of the other, the looking that comes from elsewhere than the mere look. In the gaze of the other there is a trace of a withdrawn depth, which thus is betrayed without presenting itself, without becoming present, without being captured even in the look. In this connection, discerning such a trace of recession is the only way of resolving the conundrum involved in seeking to reveal something intrinsically concealed, something that can be brought to light only at the cost of violating its intrinsic character. The looking of the other, this recession from all that can emerge through sense, must be disclosed without being disclosed. Here the time-honored pairing and effectiveness of intuition and presence loses its pertinence and is replaced by the momentary transgressive discernment of the trace.23

The trace of recession indicates without making present, without issuing in a self-showing, a depth that as such is secured against presence. It can be called retreat—the retreat into which withdraws whatever bears on the proper without being present and without showing its relation to the proper. It can be called seclusion or secludedness—the seclusion in which images are kept apart from being one’s own and from being such as to be also, duplicitously, of the object.24 Though, while in seclusion, they do not simply cease to be one’s own, they subside into a depth that the proper cannot sound. Hegel calls it the nocturnal pit, mine, or shaft (Schacht) of slumbering images, the dark depth of images that lie concealed25 Derrida glosses these descriptions by referring to images “submerged at the bottom of a very dark shelter”; or, turning these passages so as to allude to the shining of which images are capable when drawn up from the depth, he says that they are “rather like a precious vein at the bottom of the mine.”26

This retreat, seclusion, or shelter indefinitely exceeds the proper and does so in the direction of depth. It constitutes a concrete infinity that is recessional, profound, and unfathomable in character—that is, a second proper elemental. The mode of finitude that consists in being exceeded by the infinity of retreat, of seclusion, lies in being exposed to the upsurge of images—and indeed not only of images—stemming from one knows not where, images sheltered from the probings of proper apprehension.

The depth of seclusion is set, as complement, over against the height of the natural elemental. On the one hand, there is the dark depth of retreat, while, on the other hand, there is the openness and brightness of the cloudless, diurnal sky, which, of all the natural elements, concretizes height as such most manifestly. A host of other elements are donatives from the sky: thunder and lightning, rain and snow, the alternation of day and night. Even earth and sea, while not directly displaying height, supply the base from which rises the dome of the heaven; they provide the lower bound of the domain within which living beings can aspire to ascend toward the heaven, the domain in which humans can stand upright and cast their vision above.

The spacing of all natural elementals is set within the all-encompassing enchorial spacing bounded by earth and sea and enclosed by sky. It is a spacing in which the enchorial space is opened, not as an opening within a space already there, presupposed as the site of the opening, but rather in the mode of originary engenderment. It is within this space that the spacings of all other natural elementals occur. Like enchorial spacing, the spacings of the other elementals have the character of encompassing, though each encompasses in its own distinctive way. Also, earth, sea, and sky, each taken separately and so in relative independence of enchorial spacing, have their own distinctive spacing: sky is spaced as open recession, sea as the transparency that conjoins surface and depth, earth as sealed-off opacity.

The spacing of seclusion shares with sea the moment of depth and with earth that of opacity. But what is decisive in its spacing is that its depth is abysmal and that its opacity has the effect of compounding its abysmal character. The spacing is such as to open originarily a depth beneath the proper, a nocturnal pit, where images—and not only images—are sheltered and from which they can well up and shine in the brilliance of the proper. Looking down into an abyss with the aid of a sufficiently powerful light source—the sun, for instance, directly overhead—one can see that the abyss goes ever farther downward as far as one can see; and then one can imagine that it is truly bottomless or wager that it continues downward so far that no available means would suffice to allow one to see its bottom, so that, in even remotely practical terms, it would be bottomless, a paradigmatic semblance of a true abyss. But the spacing of seclusion is otherwise. In this case what is decisive is the opacity that seals off the spacing, that keeps the nocturnal pit withdrawn from the proper, apart from it, and resistant to whatever soundings might be ventured. In short, the space of seclusion is so intensely abysmal that one cannot even declare whether it is (practically) bottomless, whether it is (a semblance of) a true abyss. Precisely as its downward plunge draws one on to look—or to attempt to look—ever deeper, its opacity interferes with—not to say blocks—the view. Whether it is truly abysmal remains undecidable, and this undecidability renders it more abysmal than the abyss as such, that is, a more than true abyss. There is, then, no saying whether the images—and whatever else—sheltered in this retreat lie at the bottom of the pit (as Derrida’s gloss suggests) or whether they float in an endlessly regressive space, which would, then, constitute a kind of inverse infinity within this proper, concrete infinity.

The proper is also improper. In its broadest aspect, this conjunction demonstrates that in the logic of the proper the alleged principle of noncontradiction has no pertinence. In its more specific bearing, it indicates that impropriety or expropriation belongs to the proper as the result of the double relatedness to concrete infinity, to the properly elemental. Concrete infinity both transgresses the proper, indefinitely exceeding it, and yet belongs to it through disclosive reversion. Thus, both the natural elementals and the seclusive, sheltering retreat indefinitely exceed the proper in the direction of height and depth, respectively. In connection with both of these proper elementals, there is also reversion from the infinite to the proper, though in these two connections the reversions do not display precisely the same form. From the natural elementals, one is disclosed to oneself as encompassed, as reliant on and exposed to the elementals. From the seclusive retreat, one is disclosed to oneself as submitted to an abyss more abysmal than an abyss as such, to a more than true abyss. In the disclosure of this submittal, it is shown how one comes to be disposed, drawn into a certain disposition, by the upsurge of images, by the emergence of content from the abyss. Even in the most direct cases, as when a remote memory image is evoked by a present intuition with similar content,27 there remains an abysmal moment: not only will the memory image have lain—or floated—in the darkness of the pit, but even the manner in which it is evoked—that is, the way in which similarity of content can prompt it to ascend into the light—remains undisclosed. It is this abysmal character at the heart of memory that makes it such a suitable subject for comedy, especially for Platonic comedy, in which—as with the example of the aviary in the Theaetetus28—abstraction from the abysmal is feigned in such a way that it then comes to be revealed as such through the enactment of the resulting comedy.

Submittal to the abysmal character of the seclusive retreat involves, not only disposition, but also reliance. Without the resources sheltered in the abysmal retreat, memory would be limited to what has remained simply one’s own, that is, to what one can, purely through one’s own agency, call up. Even the enormous store of language would be limited to the sphere of the proper, as if we were not more possessed by language than language by us.

There is still another aspect in which the proper is also improper. There is another concrete infinity, another proper elemental, to which the properly human sustains a double relatedness. But in this case both the excess and the reversion are intensified. Though it remains indefinite, the exceeding is such that its term, the concrete infinity, cannot, in principle, be made present, in the way in which, most manifestly, the natural elementals can be made present. Its withdrawal, the force of the transgression, has in this case an absoluteness that is lacking in the case both of the natural elementals and of the sheltering retreat: it is entirely absolved from presence, from being presented. In this case the reversion also assumes a different form: rather than giving one back to oneself in the sense of a self-disclosing to oneself (for instance, as encompassed), this proper elemental gives one oneself as such. Though it beckons from its anterior remoteness, one’s own birth can be neither represented (without dispelling that very ownness) nor reenacted by means of memory or imagining. With respect to what is one’s own, birth both is absolutely anterior and is the onset of all enabling. The double relatedness to birth, as to an absolute excess that, in reversion, absolutely bestows, constitutes natality.

The other proper elemental is complementary: equally absolved from presence, death deprives one of oneself. In sleep one is for a while stolen from oneself, as attested in the words with which the poet lets Helena express her wish:

And sleep . . .

Steal me awhile from mine own company.29

So in death such theft is extended without limit: one is stolen from oneself absolutely. Like birth, it beckons from afar, yet from a posterior remoteness. And though, on the one hand, its posteriority is absolutely resistant to representation and imaginary enactment, it is, on the other hand, a posteriority that, like the anteriority of birth, stretches across the entire span of life. Relatedness to this proper elemental constitutes mortality.

The four proper elementals, namely, the natural elements, the sheltering retreat, birth, and death, delimit, in their transgressive bearing on the proper, the space of propriety. The character of these proper elementals, along with that of the corresponding moments of finitude, makes it abundantly evident that neither the proper (one’s own as such) nor the proper compounded (and expropriated) by its relatedness to the proper elementals is to be identified as an interiority. The properly human is not a “within” (which could be conceived, for instance, as an indwelling soul) that somehow has to break out from itself into a “without,” an “outside.” Rather, it is always already extended, stretched, between birth and death, which, no matter how dissociated they may be from biological occurrences, have nothing to do with interiority. In addition, it is always already engaged with nature and the natural elementals and does not have first to escape from itself, to turn itself inside out, in order to engage all that belongs to nature. Furthermore, this engagement cannot be separated from what has been called the body, which, almost always determined in subordinate opposition to the soul, would, with the dissipation of interiority, require unsettling displacement and thorough redetermination. Even in the case of the sheltering retreat, which could most readily suggest an interiority, its character as infinite exceeding and as abyss would require conceiving it as an interior of the interiority, disrupting its conception as simply interiority. For a consciousness (to introduce this now dubious designation only in this negative connection) exceeded by an abyss belonging precisely to it would not be simply consciousness; but, at the very least, such a conception would broach the enormous difficulty, not to say aporia, that necessarily haunts a discourse on the so-called unconscious.

It has been called darkness, not just the darkness that descends in the night to enshroud all things, but that of an interminable night, a darkness that even the blinding light of the sun cannot finally penetrate and dispel. It is the darkness of a night that offers no promise of a dawn to come. Yet it condemns nothing unconditionally to eternal darkness. There is nothing—or almost nothing—that is totally incapable of escaping its shroud, if only for a time, nothing that cannot emerge into the light of day. Nonetheless, every emergence remains, as with Eurydice, bound to the threat of falling back into the nocturnal pit. The threat becomes uppermost at the moment when the madness of the day intervenes to turn its gaze back into the somber depths.

It has also been called the unruly: not only as the symmetrical opposite of rule, order, form, but also as what underlies all that displays the rule of order and form. It is an illogic that lies at the basis of logic; or, more precisely, it is a manifold that requires a logic twisted free of the demands of Aristotelian logic, that requires a logic extended into the exorbitant. In this case the directionality of the exorbitance is toward depth, toward ground, and the exorbitance consists in the persistence with which the unruly remains in the ground yet as though it could, at any moment, break through once again. Indeed it does break through in its most characteristic—if less disruptive—manner whenever a phantasy floats before the mind’s eye, or a memory wells up, or a word or expression comes to bear an intention and carry it toward fulfillment. It breaks through whenever something comes to light from one knows not where, whenever something from the enshrouded depth intrudes upon the proper, offering a display—if always from behind a veil—of both the infinity and the reversion of depth. Though the unruly has also been called ground, it is not the ground that invites and endures sunlight and rain, not the ground on which, self-possessed, humans can stand erect. It is a ground that, even more than a cave, is sealed off, verschlossen; or rather, it is a ground that has, from the beginning, already caved in under its own weight, a ground become abyss, an abyss become still more abysmal, a secluded infinite indefinitely exceeding the proper while also holding it in submission, installing impropriety within the proper, expropriating it.

Seclusion is this self-closing movement in which all that is sheltered in seclusion as well as the sheltering and the shelter itself are secured in their withdrawal from presence. Seclusion is both the nontopological place of enshroudment and the securing of all that will have descended into its depths or that will, from the beginning, have been confined there. Mythically it is Hades and its shades—except that it is no more the region of death than of birth. Put otherwise—still mythically—it affirms the possibility that Orpheus could have not turned his gaze back toward the abyss but through the power of love and music could have brought Eurydice back to the upper world of light.

Seclusion is infinite. It is not the infinite (for, as in mathematics, there is no single—kind of—infinite) but rather an infinite, the infinitude of which is to be differentiated from that of the elemental in nature. As infinite, it indefinitely exceeds the proper; its exorbitance lies in the direction of depth, of a depth that is self-closing, doubly abysmal. Though archaic, it takes place principally as concealment. In this word the same polysemy is displayed as in seclusion: it designates the space in which all that remains intrinsically concealed is sheltered in concealment, while also it includes in its semantic field both the operative spacing and the consequently concealed. Concealment is no less abysmal, no less radically abysmal: that something is concealed can itself be concealed—that is, concealment can be compounded through self-concealment. In this case concealment is sealed off, becomes imperceptible. As long as one sees the veil, one can venture to draw it aside so as to reveal what lies behind it. But when the veil itself becomes invisible, no direct strategy suffices to dispel the concealment; indeed what happens—except in very exceptional cases—is that one remains oblivious to the concealment, unaware that anything lies in concealment.

The relatedness of the proper to seclusion is, as with all proper elementals, bidirectional. This relatedness constitutes a moment of human finitude. As, in one direction, seclusion indefinitely exceeds the proper, so, in the opposite direction, there is reversion from seclusion. Through this reversion the human, exceeded by an infinite, is given back to itself, granted self-disclosure.

What is disclosed to the human in this fashion is sheer advent: something comes with no seal of origin; it comes without inscribing any legible trace of its genesis. It can, then, only have been released from behind the veil of seclusion: perhaps called up, prompted, by something apprehended, by something that calls for it; but perhaps, if the veil is invisible, by a more circuitous way. For instance, as one openly intimates a still shapeless and inarticulate concatenation, a word may come to crystallize the sight and the ordering that gives it sense. Or, a momentary glimpse of a landscape, the bouquet of an excellent wine, the night sounds of the woods in summer—all can prompt the arrival, as if from nowhere, of memories and sequences of memories, of phantasies, some of which are barely distinguishable from memories. Also, a brief, utterly insignificant everyday event or observation (a casual glance in a shop window) can, according to Freud’s analysis, prompt a dream in which “the dark powers in the depths of our soul” well up.30 The nowhere from which these all come, this unlocatable spacing, is seclusion.

Yet seclusion engenders not only fitting words, prompted memories, phantasies, and dreams; from behind the invisible veil, releasing what it will, it disposes humans in one way or another, gives them a certain bearing, a certain inclination, toward things and toward other elementals. It bestows on each a singular openness and directedness toward all that is encountered. It attunes each in a certain register, and it is precisely in this state of attunement, from out of it, that humans then—and only then—come to apprehend things. It is from out of—within the spacing of—this disposition that even the most direct and primary relation to presence, that of the sense-image,31 takes place. In its antecedence, disposition forms the proper by deforming it; and as such it constitutes the distinctive texture that belongs to seclusion.

As with all elementals, seclusion is to be rigorously distinguished from things. Indeed seclusion does not display even the affinity that natural elementals have with things, at least to the extent that such things belong directly to nature. The categories and principles by which, from Aristotle on, the field of things is determined have not the slightest applicability to seclusion. Since it manifests itself only as self-concealing source, nothing warrants ascribing to it such determinations as substantiality (even as οὐσία), causality, qualitative reality (Realität), or quantitative unity. Even more originary determination as the enclosure of a sense-image by various systems of horizons is entirely inappropriate. Insofar as the transcendental (in distinction from categorial) determination signified by the word being (in its various forms) extends only to things, discourse on seclusion and indeed on all elementals requires that the sense of being be accordingly displaced, not to avoid contradiction (which can be highly productive) but to maintain the minimal coherence needed for signification to remain operative. In the interest of a discourse accordant with the differentiation of elementals from things, it is imperative that the sense of being be made mobile.

But then the sense of negativity will also be mobilized. To being as a transcendental determination extending to the entire field of things, there is opposed nonbeing, negativity, or, in Hegel’s idiom, abstract negativity. When the sense of being undergoes the displacement from substance to subject, which is “expressed in the representation of the absolute as spirit,”32 then the sense of negativity undergoes a profound shift. No longer is it the mere opposite of being, something from which one simply turns away as a mere nothing and from which then one passes on to something else, to something substantial, something that truly is. Rather than such a mere turn away, what the new sense of negativity requires is endurance. Spirit is the power of such endurance. In an assertion so decisive that its consequences remain, even today, unlimited, Hegel writes: Spirit “is this power only by looking the negative in the face, tarrying [verweilen] with it. This tarrying is the magical power that converts [or inverts, turns upside down—umkehren] it [the negative] into being.”33 No longer a mere opposite of being, negation is comprehended as determinate negation, as always the negation of some content, hence as turning into being.34 In every sense of the expression: nothing is lost. Whatever is negated is recovered, given back to itself as a new form at a higher level.

Aside from his own multiple strategies for marking certain fissures in Hegel’s text (he once said, in fact, that he would never be finished with the reading and rereading of Hegel’s text),35 Derrida has set clearly in focus Bataille’s athwart resistance to Hegel’s concept of determinate negation and to the systematic structure that it makes possible. Over against the Hegelian imperative that “there must be meaning [sens], that nothing must be definitively lost in death,”36 Bataille, to the contrary, calls for “the deepest foray into darkness without return.”37 He attests—says Derrida—to an “absolute comicalness,” obliquely opposing comedy to the serious work of the Hegelian concept (as if Hegel had not elevated comedy to the pinnacle of art). What Bataille finds absolutely comical is “the anguish experienced when confronted by expenditure without security, by the absolute sacrifice of meaning: a sacrifice without return and without reserves.” He counters what is expressed in the concept of Aufhebung, namely, “the busying of a discourse . . . as it reappropriates all negativity for itself.” To engage such discourse is to blind oneself “to the groundlessness of the non-meaning [au sans-fond du non-sens] from which the ground [le fonds] of meaning is drawn and on which it is exhausted.”38

It is, then, a question of appropriation, of whether it is possible to assimilate everything to the proper without loss, without remainder. The failure to comprehend the impossibility of such appropriation constitutes, according to Bataille, the blind spot of Hegelianism. Yet even to refer to a failure of comprehension, hence to the possibility of comprehension, is to appeal to meaning as the correlate of comprehension and thus is not yet an absolute sacrifice of meaning. Only in absolving oneself from meaning, only in embracing noncomprehension, could one regain one’s sight of the groundless nonmeaning. Yet such sight could not but be senseless, devoid of comprehension, an utterly nondisclosive comportment—in a word: ignorance, indeed an ignorance incapable of sustaining discourse on what would have been—almost blindly—seen. Little wonder, then, that Derrida marks the limit, the point of no return, “which no longer leaves us with the resources with which to think of this expenditure [without reserve] as negativity.”39 Derrida concludes: “In sacrificing meaning,” he “submerges the possibility of discourse.”40

There is a very remarkable passage in Inner Experience that could be read as Bataille’s appeal to his last resort. It is no accident that it occurs in a section entitled simply “Hegel.” The passage begins with Bataille’s confession that it is his last resort, his final recourse, or, as he puts it, “ultimate possibility.” Immediately he identifies this possibility: “That non-knowledge still be knowledge”—that is, that in the “without reserve” there remain somehow—but how?—a reserve of meaning. Then, most remarkably, he writes: “I would explore the night! But no, it is the night that explores me . . .” The ellipsis with which the passage ends belongs to it.41

The night cannot be made one’s own. It can be neither a possession nor something to be taken to heart. No one owns the night. It simply comes; and after nightfall one sees a more somber landscape and senses a depth that bears on, but exceeds, all that is most one’s own.

Darkness, the unruly, seclusion cannot be appropriated, absorbed without remainder into the proper. Yet the remainder is no fund of nonfundament, of non-sense, which would emasculate discourse, but rather consists in the removal of the infinite from the proper, in the indefinite excess by which seclusion is set apart from the proper, yet in such a way that, in reversion, its reserve comes to bear on the proper and thus is opened to meaning and discourse. It is in this birelationality that the negativity of seclusion consists.

Yet in the case of seclusion, negativity assumes the specific guise of concealment. The compounding of concealment provides the basis for a distinction that is parallel, though only up to a point, to the psychoanalytic distinction between the preconscious and the unconscious. Whatever is merely concealed is never entirely hidden from view, never inaccessible; rather, it is simply that which is not properly entertained, not truly apprehended (in the broadest sense), but which can be prompted to become so, which can be called up as if drawn to the proper. Such seclusive moments are exemplified by the word that comes to crystallize a vague conception or the figure that comes to inform a scene. These moments and their way of being called up correspond, in psychoanalytic conceptuality, to the preconscious.

Yet concealment can be compounded into self-concealment, into concealment that is imperceptible as such, into the invisible veil. In this case the seclusive moments are, like the locus and operation of seclusion, withdrawn into virtual inaccessibility. And yet, it must be possible—even if unaccountably, even if without direct prompting, even if only for an instant—for these seclusive moments to come to bear on the proper, and indeed in such a way that their more radical character is displayed, though its deciphering may well require a hermeneutics that hardly yet exists. The self-concealment to which these moments may—most indirectly—be referred is parallel to what psychoanalysis calls the unconscious.

In the relationality between seclusion and the proper, there are, then, both overt and covert moments. It is imperative, however, that what Freud calls the preconscious and the unconscious be rethought as overt and covert seclusion, respectively. This requirement stems, first of all, from the inadequacy of the concept of consciousness as such. There is no need to repeat once again the demonstration that to the degree that the concept of intentionality is thought in a radical fashion, it has ever more decisively the effect of dissolving the interiority by which the concept of consciousness is determined. The consequence, that the human is not to be conceived as an interiority, as an inner self, is extended in a positive fashion in the determination of the human as the space of propriety.

Yet even aside from these philosophical developments, many of Freud’s own remarks justify suspicion about the rigor—or lack thereof—with which this concept is determined in his analysis. For example, near the beginning of a text expressly meant to explain the unconscious briefly and as clearly as possible, Freud prepares his account by stating what is meant by conscious. The vacuousness and circularity of the statement are startling: “We would like to call conscious the conception which is present in our consciousness and which we perceive.”42 Another passage, this one in The Interpretation of Dreams, offers an equally inept, if less circular, definition of consciousness, which, says Freud, “means for us a sense-organ for the apprehension of psychical qualities.”43

On the other hand, Freud cannot avoid granting to consciousness a certain privilege, identifying it as the starting-point of his inquiry. For instance, near the beginning of the text “The Unconscious,” he draws explicitly the distinction between the preconscious and the unconscious. He describes the preconscious as consisting of acts that are temporarily unconscious but otherwise no different from conscious ones; to characterize the unconscious in the strict sense and in distinction from the preconscious, he refers to repressed processes, which, were they to become conscious, would contrast strongly with conscious ones. Freud alludes to ways in which the distinction between conscious and unconscious (in the strict sense) could be rendered inoperative, but since, as he declares, these ways are “impracticable,” the ambiguity involved in using these words in both a descriptive and a systematic sense must be tolerated. He proposes to avoid confusion to some degree by using “arbitrarily chosen names” for the two systems, names that make no reference to consciousness; yet oddly enough it turns out that these names, alleged to be arbitrarily chosen, are simply abbreviations for conscious (Bw for bewusst) and unconscious (Ubw for unbewusst). In fact, just as he is about to introduce these abbreviations, he grants, in effect, the futility of seeking to avoid the ambiguity and confusion that surround these concepts and distinctions. He says that in distinguishing between the systems (Bw and Ubw) “one cannot evade [umgehen] consciousness, since it forms the starting-point of all our investigations.”44