ON A SUNDAY in the spring of 2005, we were out watching the LPGA Safeway International at Superstition Mountain, not far from where we lived in Phoenix. Legendary Mexican golfer Lorena Ochoa had just birdied the 15th hole, and now led the tournament, and Annika Sorenstam, whom she was paired with, by four strokes. With just three holes to play, it looked like Lorena had the tournament in the bag as they moved to the 16th hole. Lorena had double-bogeyed the hole the day before, and shockingly, she double-bogeyed it again. Annika made her par. Now Lorena was just two strokes ahead.

They teed off on 17, a par 3. Annika made another par. Lorena three-putted from seven feet for another bogey. Now Lorena led by only one shot as they headed to the final hole. No. 18 on the Prospector Course is a par-5 hole with a long, narrow lake hugging the left side of the fairway. It’s the only water on the course. Both players’ drives landed in the fairway. Then Annika hit a second shot that she later described as one of the best approach shots of her career. The ball landed 22 feet from the hole. Lorena reached the green in regulation. Annika two-putted with a tap-in birdie to tie, and force a playoff.

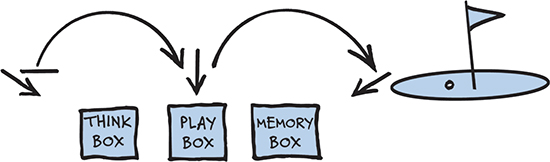

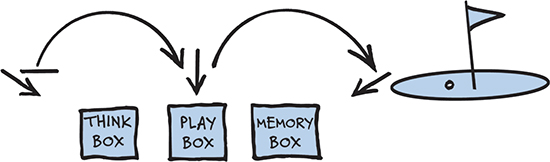

Here’s where things got really interesting. Lorena and Annika went back to the 18th tee for the sudden-death playoff. As Lorena was deciding on her shot, we watched her make the sign of the cross in the equivalent of her Think Box. Then she stepped into her Play Box. She had a 3-wood in her hand. Shockingly, she drop-kicked her shot; the club took a divot on its way to the ball, and she yanked it left into the water. Victory to Annika.

Because Arizona is close to Lorena’s home in Mexico, she had a group of about 200 people—close family, extended family, friends, and fans—following her that day. When she finally walked off the 18th green, they all gathered around her, crying and hugging her, trying to console her. It was like a funeral. We looked at each other and didn’t even need to say the words aloud: Lorena needs to be extremely careful about how she stores this memory.

Another of the essential lessons to understand about golf is the importance of memory and how it affects performance. It’s why we have made Memory Box the dramatic finale to the Think Box–Play Box performance routine.

Memory is powerful. It’s a central construct of our identities. Memory is the physio-neural mechanism by which we encode, store, and recall information important to our lives. Memory gives us the capability to access previous experiences, as well as to adapt to new ones. Neuroscientists describe memory as the retention, reactivation, and reconstruction of an experience-related internal representation. In other words, when we experience something, it gets imprinted and internally represented in specific areas of our brain, particularly the amygdala, which is in the oldest part of our brain.

Long ago, memory literally helped us survive. We needed to identify and remember dangerous things that might kill us—snakes or lions, for instance. Memory enabled us to avoid them and survive. The same mechanism still works in our brains today. For instance, as children not knowing better, we might touch a hot stove and burn our hand. We experience the sensory and emotional feeling of pain, and we might cry. Our brains store the association—hot stove = pain—as a memory. The more emotionally charged the event or experience, the stronger that memory will be. Here’s the fascinating thing: Our brains don’t make a distinction between a snake and a hot stove, or a hot stove and a golf hole that gives us fear. They’re all the same to the brain, if it associates the object with danger.

Several months after Lorena’s disaster in Phoenix, we were at the U.S. Women’s Open at Cherry Hills Country Club in Denver. In the final round, Lorena was three strokes behind the leaders at the turn, and making a thrilling Sunday charge. With four birdies on the back nine, she had taken the lead by one stroke as she approached the 18th hole. The 18th hole at Cherry Hills is a par 4 with water hugging the left side. It was similar enough to the 18th hole at Superstition Mountain in Phoenix. Lorena and her caddie had an intense conversation before she took the tee. She was holding a 3-wood in her hands. She looked tentative. As she swung the club, she came out of her shot and drop-kicked the club into the dirt—just as she had done in Phoenix. The ball veered left into the water. Lorena finished the hole with a quadruple-bogey 8 to lose the tournament by four strokes.

Johnny Miller, who was commentating for NBC, quickly connected the two events. “Lorena did the same thing earlier this year in Phoenix,” he said with astonishment. He then showed a side-by-side comparison of her two swings. “This seems to be a pattern,” he said, identifying the error as a repeating technical flaw in her swing.

A couple of months later, we ran into a friend of Lorena’s. “You need to hear the rest of the story,” the person told us.

Our source shared that as Lorena stood on the 18th tee at Cherry Hills, she said to her caddie, “I’m not sure about this. I feel like hitting a 4-iron.” Her caddie argued with her. “You’re playing great, Lorena,” he said. “There’s plenty of room for you to hit a 3-wood on this hole.”

“But I feel like hitting the 4-iron,” Lorena insisted. Her gut was telling her to hit a different club. And she let her caddie talk her out of it.

Johnny Miller had identified her problem as a repeating technical glitch in her swing. He was right about the technical glitch, but only partly. Miller was going with external cues. The other truth, in our opinion, was an internal cause: Lorena’s stored emotional memory showed up in her technique.

Let’s analyze what happened to Lorena at Cherry Hills through the filter of memory. She approaches the 18th tee and sees the hole with water on the left. It’s the last hole of the tournament, the pressure is on, and she has a 3-wood in her hand. Her brain recognizes it as similar to the hole at Superstition Mountain. Lorena’s brain sends a signal: Water on the left! Hot stove! Snake! Danger! It was telling her to do something—anything—different, so she wouldn’t repeat the result. Lorena tried to ignore her gut instinct to hit her 4-iron. But if you’ve touched a hot stove, the brain will always remember it.

Here’s another super-important fact about memory. Psychological research has shown that humans have a 3:1 negativity bias as our default setting in storing memories. The brain naturally stores negative memories faster and stronger than positive ones. Neuroscience and evolution give us a simple explanation. It was much more important to remember danger and threats long ago than to remember positive or happy incidents. If we remember the snake and the hot stove, we are more likely to avoid them—and survive. On the other hand, when we store negative memories, consciously or subconsciously, we are prone to triggering those memories and emotions when we encounter similar experiences.

Recently, we conducted an informal experiment. We asked golfers in the middle of a round, and after the round, how things were going. Nearly everyone said something negative. “If I hadn’t missed that shot on the 14 hole, I’d have had a great round.”

“Those three-putts really killed me.” We describe our own games more negatively than those who are watching us, which is why we need to be aware.

We need human skills to neutralize negative memories, and store positive memories more strongly. If Lorena had been prepared to address this situation properly, she might’ve finished off that U.S. Open win.

Here are the simple facts of golf. When we’re ready to hit, the ball is sitting at Point A. We use a club to propel it to Point B. Point B could be the middle of the fairway, in the water, off the property, and sometimes, Point B could even be in the hole. Point is, there is always Point B.

Then there’s you, the golfer—an emotionally complex human who is extremely invested in Point B, that is, the outcome of the shot. When we hit a good shot, we feel exhilaration: Wow! My ball’s on the green six inches from the hole! We celebrate, we high-five our partners. But because it’s not good etiquette to celebrate too much, we quiet down and move on to our next shot.

When we hit a shot that lands in the water, disappears into the deep rough, or soars out of bounds, we curse ourselves, slam our clubs, or find something to blame. Damn, it’s in the water! I hate this hole! I let my elbow fly out again! Depending if your past experience was positive or negative, when you face a similar shot in the future, you’ll find yourself feeling relaxed and confident, or you’ll walk up to the ball and think, Uh-oh. Your body might begin to feel a little tension. Absolutely nothing has happened yet, but your palms are getting sweaty. Unfortunately, the memory function in the brain doesn’t have a delete button. It doesn’t move our bad shots to the trash.

Remember, the brain stores negative memories three times more strongly than it stores positive memories.

So what can we do?

The Memory Box is the third and final part of your performance routine. Using the Memory Box skill, you can learn to be emotionally objective and neutral after bad shots, and reinforce your positive emotions after your decent, good, or great shots. For us, there are two things that are useful to evaluate after every shot: your process (how you executed your Think Box and Play Box) and your outcome (the quality of the shot and where the ball landed).

Let’s review. You’ve decided on your intended shot in your Think Box, and committed to the sensory feel to use in your Play Box. Here’s your first Memory Box practice goal: After you hit a shot—any shot—hold your swing until the ball comes to a stop. The 15 to 20 seconds after your swing are vital to how your brain stores a memory. By pausing and staying in your Play Box, or even taking a few breaths as you put the club in your bag, you’ll avert a premature negative emotional response to the outcome of the shot. When the ball lands, allow yourself only two reactions: objective or positive. Make these the only two choices for your Memory Box, if you want to fulfill your potential as a golfer. We’re not telling you to forget your bad shots—we’re asking you to be objective about them.

You may categorize your Think Boxes and Play Boxes as Not Good, Good Enough, Good, or Great. Your reaction to your shots and processes that are Not Good will be objective; your reaction to Good Enough, Good, and Great shots and processes will be some degree of positive feeling. An objective reaction states the facts: The ball is in the bunker; I lost my balance in the backswing. You will store Good Enough, Good, and Great shots and processes with a positive feeling. Being positive to your Good Enough shots is one of the secrets to optimal performance. It’s not about lowering your standards, but about seeing and playing the game with the right mind-set. Move on, and look at the trees, sing a song, or count the dimples on your golf ball as you head to your next shot. We guarantee you will play better, and enjoy yourself more.

Alternatively, soak up the experience of your Good Enough, Good, and Great shots. And absolutely celebrate, internally or externally, your Good and Great shots. In doing this, Memory Box becomes the all-important third step of your performance routine.

Here’s how Memory Box might look in different situations on the course. In Scenario 1: You stroke an important putt for birdie, but the ball slides three feet to the right of the hole. You say to yourself, “Okay, I obviously misread the break, so next putt, I’ll pay closer attention to reading the green (I’m being objective). But I’m happy about how I stroked the ball and held my motion to the finish. I kept my Play Box focus on finishing my stroke, so I’m positive and happy about my process and the stroke—good.”

See? No negative memories.

Scenario 2: You pull your drive into a bunker. Again, your reaction is to stay neutral and objective to the outcome: “Okay, the ball is in the bunker, but I’m confident about my bunker play.” What about your process? You wanted to swing at 70-percent tempo in your Play Box, but instead you swung at about 110 percent of your normal tempo. Next time, you’ll deepen your focus on your tempo and try to be more present in your Play Box. You’re neutral and objective about your swing, which is your process. You’re not denying what happened, but you’re not beating yourself up, either. Your Memory Box for this shot is neutral to outcome, neutral to process. You won’t store any negative memories.

Scenario 3: You’re a scratch golfer and you hit a wedge from a great lie to 20 feet left of the flag. You know you didn’t stay with the feeling of “soft shoulders” all the way to the finish. You chose to be objective to your process, but you’re still putting for birdie, so the outcome is Good Enough.

Or, you hit a fade off the tee. You wanted to hit a draw, but it ends up a lot shorter than you anticipated. You’re objective to your process, since you didn’t stay with your Play Box long enough, but you’re in the fairway and have a good chance to hit it on the green. So the outcome is Good Enough.

Scenario 4 (this is extreme, but that’s why we like it): You mis-hit your tee shot on a par 3, and the ball never gets airborne. It keeps rolling, but somehow the ball ends up in the hole. We’d be totally yippy-skippy about the outcome—a hole in one!—and we’d stay neutral and objective about the process, which was hitting it thin, and our center of gravity got really high. In this scenario, we’re positive to outcome and neutral to process. No negative memories.

The important human skill is exercising choice about your reaction to your shots. Manage your reactions. Don’t be blasé about your good shots. Give yourself a pat on the back, or a good fist pump, and feel some degree of happy. We see players who hit great shots and act like it’s a routine event, because they’re overachievers and think they should be hitting great shots all the time. But they’re hurting themselves by not storing positive memories. This skill isn’t about the power of positive thinking. It’s about the necessity of understanding your brain’s negativity bias and creating neutral or positive emotional states after your shots. Your brain will take care of the rest.

If we had been Lorena Ochoa’s coaches, this is how we might have worked with her after her debacle: First, we would have told her, “Listen to your gut’s ‘no’ signals.” If your gut is signaling it doesn’t like the shot or the club, step out of the Play Box. Change your club, choice of shot, or Play Box focus. Make sure you have a “go-to” shot you can use under extreme pressure. Understand that these situations will happen, and be ready to shift your plan of attack. If you see water on the left and your gut brain reacts, trust it. Hit your 4-iron, or a fade with your driver, or hit a low punch shot with the 3-wood. First and foremost, listen to yourself. Do not step into the Play Box if you’re trying to force something. Instead, make a change.

We work continuously with players on Memory Box skills, so they’ll learn to be factual and objective to bad shots. And we work on creating more positive memories to store. Sometimes players will need to re-create the situation of a negative memory to override it. Lorena could have gone back to the 18th hole later that evening, or early the next morning, and created some Good Enough, Good, and Great memories to store. She also could have worked on re-creating those situations in visualization or imagery on the range. She could have become neutral about the original shot, then stored a positive memory about her process.

All players need to train these Memory Box skills. Pia has trained her own skills for so long, they’ve become habit. She’s Positive Pia.

We’ve seen extraordinary turnarounds in people’s games with this one skill. Suzann Pettersen took control of her Memory Box, and learned to be more objective about her missed shots and more positive about her good ones. Interestingly, youngsters who take our junior clinics get this right away. One 12-year-old boy started nodding when we explained Memory Box and blurted out, “Oh my gosh! I wish I had learned this when I was 8.” The other thing kids regularly say to us is, “Could you please teach this to my parents?”

One more point: Positive and negative memory storage can endure long after the shot. For amateurs, when you’re having a beer at the 19th hole after your round, be aware of what you and your friends are talking about.

“Did you see my shot that went in the water?”

“I can’t believe how many three-putts I had today.”

“If I hadn’t hit that shot into the rough on 16, I’d have had my best score of the season.”

Professional golfers need to take extra care of their Memory Boxes. If they triple-bogey or three-putt a hole during a tournament, reporters will surely ask them about it afterward, likely over and over again. The players need to be mindful about how they answer. Annika Sorenstam became a master at this skill. If she was asked about a double bogey she’d made, she would answer, “Yes I double-bogeyed that hole, but it was what happened afterward that was important. I committed to every swing after that hole, and I came back.” She refused to over-emotionalize a mistake and replay it.

PGA Tour pro Chris DiMarco learned the skill after he finished playing a round with Tiger Woods at the Masters. DiMarco was listening while Tiger did his interviews. Tiger talked about how well he hit the ball during the round and the great shots he’d made. Afterward, DiMarco shook his head. “I just played with the guy. He hit it terrible out there today!” At that moment, he says he realized that Tiger was taking control of his memories of the round. Tiger had an important skill he didn’t have. DiMarco began to practice it, and it led to big changes in his career.

“I’ve observed that if most professionals have one weakness, it’s their Memory Boxes,” says former PGA Tour player and VISION54 student Arron Oberholser. “Good players tend to be proficient with their Think Boxes and Play Boxes, because that’s the heart of playing at a high level. If you’re a player who’s breaking 70 on a regular basis, you’ve probably got good skill-sets in your Think Box and Play Box. But when you’re competing under intense pressure, and you’re not able to put aside a poor shot, that’s what separates the winners from the rest of the field.” Arron added: “For my career, taking control of Memory Box was the thing that elevated my game to the next level.”

Russell Knox knows that Memory Box skills can make a huge difference in performance. “You can have two equally talented golfers standing next to each other hitting the ball identically, and one of them goes out and wins the tournament, and the other one goes out and misses the cut,” Knox says. “You’re like, ‘Okay, what’s the difference between those two?’ One of them reacts negatively to his poor shots, and allows his emotions to get control of him. He has no chance against the player who can control his emotions, and his outlook, during a round. Far too many people, professionals and amateurs, spend a lot of time complaining. You hit a shot that’s not quite what you wanted it to be. You get down on yourself. But golf isn’t a game of perfection. It’s about managing your bad shots and your emotions. Most times, those shots will be good enough.” When he hits a so-so shot, Russell says he catches himself on the verge of complaining, and he hears Pia’s voice. Is it good enough? You’re still going to be able to make a par. It might not be a birdie, but it’s good enough.

Russell used his Memory Box skills to near-perfection when he won the WGC-HSBC Champions in Shanghai in 2015. When he made the turn on Sunday, he was tied for the lead with Kevin Kisner. Russell birdied holes 10 and 11 to give himself a two-shot advantage.

“I was thinking to myself, ‘Okay, I trust my short game, and I trust my recovery game. Don’t get mad at yourself if you hit it in a fairway bunker, hit it in the rough, or miss a green. Trust your ability to make a par.’ That day I hit some shots that weren’t great, but I didn’t store them in a negative way. They were good enough. I kept making pars, and eventually I birdied 16, which gave me a three-shot lead with two holes to play.

“It’s something I’m going to keep with me for the rest of my life,” Russell says. “Golf is a tough game. When you’re out there under pressure, you have to be good to yourself and not beat yourself up. Being so close to winning, I knew I couldn’t afford to be negative. I remember thinking that even if I hit it in the water on one hole, I’m going to stay objective to the outcome and tell myself, ‘That was a good swing, Russell.’ ”

ON THE COURSE, we don’t use the word practice very much, because we tend to think about it differently than most people in golf. Some golf clubs have explicit policies in their rule books: NO PRACTICING ON THE COURSE. Their interpretation of practice is hitting lots of extra balls, taking extra chips around the green, and putting several putts—which beats up the course and holds up play. That’s why we prefer to say we’re going out to “learn,” “train,” or “explore” on the course. Look at these questions and explorations as a new kind of practice.

Memory Box skills don’t come alive until you put them in context on the course. This is where our patterns and negativity biases show up, something that doesn’t happen on the range. Do these Memory Box questions and explorations. Keep practicing them!