RUSSELL KNOX SAYS he hears Pia’s voice in his head when he’s competing in a tournament. “When I hit a so-so shot and I’m just about to complain or make a stupid comment to myself, Pia is always there,” he says with a laugh. “She’s saying, ‘Is your shot good enough, Russell? I’m sure it is. You’re still going to be able to make par. It might not be the best shot you’ve ever hit, but it’s going to be good enough. You’ll be okay.’ ”

Every player encounters setbacks on the golf course. This is the nature of variability. You will misjudge or mis-hit a shot. The weather will take a turn for the worse before your tee time. Your ball will hit a sprinkler head. Then, there are times when bona fide disaster strikes, usually in the greatest pressure moments: Greg Norman’s collapse at the finish of the 1996 Masters; Lorena Ochoa drop-kicking her drive into the water on the 18th hole at the 2005 U.S. Women’s Open; Ariya Jutanugarn’s implosion during the last three holes of the 2016 ANA Inspiration; Jordan Spieth’s quadruple-bogey 7 on the 12th hole of the 2016 Masters; or Phil Mickelson’s disastrous 18th hole at the 2006 U.S. Open.

Now we’re going to tell you a disaster story about one of the players we coach. This should illustrate both the challenge and the power of using your human skills in the most stressful situations you’ll encounter.

Russell Knox has lived in Jacksonville, Florida, for almost 15 years. He has played TPC Sawgrass’s Stadium Course more times than he can remember. During all those years, he has never hit a tee shot into the water at the par-3 17th hole.

During the third round of the 2016 Players Championship, Russell stepped onto the tee box of the famous island-green 17th hole and prepared to hit. He was 8 under par, among the top-10 players in the tournament. Russell lined up his pitching wedge for the 122-yard shot. It soared into the air, and came down inches short of the right side of the green, gently splashing into the water. Russell looked stunned. His shoulders slumped.

Instead of heading to the drop zone, he re-teed his ball. As soon as he hit, his body language showed he had shanked his second shot into the water, too. He shook his head, and hit his club on the ground in frustration. Then he teed the ball up for a third time. He hit again. This time he blocked the shot slightly to the right. The ball splashed into the water, close to where his first ball had entered. Dropping his club, he grabbed his head in disbelief.

Johnny Miller was commentating on television. “I feel for him,” he said with genuine anguish. “This is a fishbowl, and Russell’s under the microscope right now.”

This time, Russell and his caddie walked to the drop zone. He hit his seventh shot safely across the water, and onto the green. Walking to the island green, he tipped his cap to the crowd. Then he two-putted for a 9, tying for the fourth-highest score recorded on the hole in tournament history. Russell finished his third round with an 80.

“It was an epic fail,” he admitted afterward to a reporter. “I thought I hit a good first shot. I thought I’d stuffed it. It’s such an easy shot when you have no nerves or adrenaline in play. But it’s a different story once you’ve hit two in a row in the water. The green feels like the size of a quarter. After that, everything goes so quickly. Your blood is just pumping through your brain. Until you’re in that position, you don’t understand what it feels like.”

We were really proud of Russell. After the hole, he understood precisely what had happened to him. He practiced textbook emotional resilience later that day, and came back on Sunday to shoot an amazing 67 to finish in a tie for 19th place. Before his round on Sunday morning, he tweeted to his 11,000 followers, SHANK you very much for all the nice messages. Looking forward to getting my revenge today!!! A few days later, he tweeted again, putting his performance on No. 17 in context: Golf has given me my career and SO much more. Let’s keep growing the game and opening people’s eyes to our sport.

EMOTIONS. WHERE TO BEGIN? According to relatively new research at the Institute of Neuroscience and Psychology at the University of Glasgow, we humans have four fundamental emotions. Three are so-called negative emotions: fear, anger, and sadness. The fourth, and only positive, emotion is happiness.

When a golfer misses consecutive shots, the experience creates strong negative emotions: shock, panic, and anxiety. Your body begins to release hormones that have a direct effect on how you perform. Cortisol is the body’s “stress” hormone. It’s composed of the same base molecules as the “happy” hormone, DHEA, and the two hormones work on a fulcrum, constantly offsetting each other. When we have high levels of DHEA, we have low levels of cortisol. When we have high levels of cortisol, we have low levels of DHEA.

As we mentioned earlier, DHEA is a performance-enhancing hormone that, among other things, acts as a lubricant to the brain. When your brain receives information while your body is experiencing higher levels of DHEA, you have access to your highest brain and motor functions. It’s as if the brain and body are a smooth-running engine. This enables your best decision-making, visual acuity, balance, timing, and rhythm. While higher levels of DHEA don’t guarantee greatness, they do guarantee access to your fullest potential.

On the flip side, when cortisol spikes in your system—as it did in Russell’s—the brain basically says “Access Denied.” Instead of sending information and instructions seamlessly through your brain and body, the engine begins to stall. Decision-making suffers—or it shuts down completely. You literally don’t see as well, and your balance, timing, and rhythm lose their coordination. Russell’s brain essentially froze as his cortisol soared. After hitting his first ball into the water, he teed the ball up for a second and a third time. Spectators must have been asking, What is he thinking? And that’s precisely the point. He wasn’t thinking.

This is why it’s important to understand what’s happening physiologically when you mis-hit a shot under pressure. If you do, you’ll be able to use your human skills to recover.

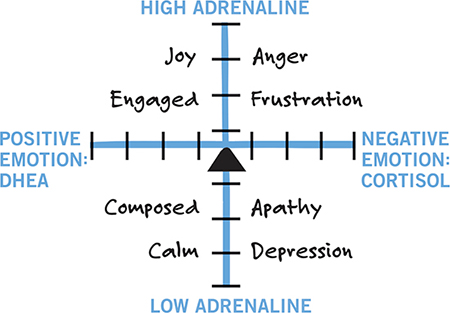

In explaining the concept to our students, we like to use this illustration of the adrenaline-DHEA-cortisol grid.

Hormones and emotions influence one another. They also interact with your adrenaline level. As you look at the grid, the vertical line is your adrenaline level. The horizontal line is your DHEA-to-cortisol continuum. In the upper-left quadrant, you have DHEA and high adrenaline. These golfers are having one of their best days on the course; they’re happy and engaged, with great access to all their mental, physical, and emotional skills. Words associated with DHEA and high adrenaline are joy, passion, pride, exhilaration, happiness, engagement, courage, and inspiration. These players are having a party on the outside (if they’re extroverts) or on the inside (if they’re introverts). Some players who show DHEA, high-adrenaline behavior (when they’re playing well) include Jordan Spieth, Tiger Woods, Suzann Pettersen, and Michelle Wie. (It’s an interesting exercise to observe the pros, and watch where they are in their quadrants.)

Now let’s move to the upper-right quadrant: high adrenaline and cortisol. Players in this quadrant are having a terrible day on the course, or have just made a huge error.

Adrenaline and cortisol are surging, shutting down their access to their best physical, mental, and emotional skills. Words associated with high adrenaline and cortisol are anger, frustration, anxiety, and terror. These players are exploding or imploding, depending on whether they’re extroverts or introverts. Extroverts throw clubs, curse, and kick their bags, and introverts fume silently. Players associated with cortisol, high-adrenaline behavior (when playing badly) include John Daly, Tiger Woods, Dottie Pepper, and Suzann Pettersen.

Next let’s go to the lower-left quadrant: DHEA and low adrenaline. These players are having a peaceful day on the course, with great access to all their skills. Words associated with DHEA and low adrenaline include calm, composure, fulfillment, ease, contentment, compassion, and appreciation. Players who exhibit DHEA and low-adrenaline behavior include Jason Day, Dustin Johnson, Catriona Matthew, Inbee Park, and Annika Sorenstam. (Oh, and you can probably add the Dalai Lama to this quadrant.)

The final quadrant is cortisol with low adrenaline. These players probably started out the round poorly, and are discouraged and demotivated. They have poor access to their abilities, and have pretty much given up on their round. Words associated with cortisol and low adrenaline include apathy, depression, self-pity, withdrawal, burnout, resentment, guilt, and boredom. Players who are in the cortisol, low-adrenaline quadrant (when not playing well) include David Duval, Ernie Els, Sergio Garcia, and Na Yeon Choi, as well as many professionals going through a tough time or becoming tired of tour life.

One amusing story we have concerning these quadrants is about one of the owners of the Chicago Bears football team who came to our VISION54 program. He listened to us talk about DHEA and cortisol, and said, “I want my running backs, my receivers, and my quarterback in high DHEA. I want my linemen in high cortisol.” One of our coaches, Kristine Reese, said to him, “I don’t think so. High cortisol is when you’re going to get your penalties.”

Of course, not all players are squarely in each quadrant. Most players are somewhere in the middle, so their behaviors are less extreme than the ones we’ve described. The important thing is understanding the adrenaline-DHEA-cortisol grid and how to develop your human skills to manage what’s happening. We see tour players arriving at the course in higher-cortisol states if they’ve gotten stuck in traffic or overslept. We also see cortisol rising during warm-ups if they don’t feel they are hitting the ball the way they want, and they’ll start getting anxious and down on themselves. You might be on one side of the grid during a round, until you put a shot into the water. The challenge is how quickly you can recognize your reaction and do something to get back to the other side. We call it “bounce-back” ability, or emotional resilience. One little shot of cortisol is like a paper cut; it’s not going to overwhelm you. But if it gets bigger, you’re going to start hemorrhaging. If Russell Knox had quickly recognized his reaction to his first shot going into the water at the 17th hole at the 2016 Players Championship, he could have stepped away and regrouped. He could have chosen a different club, ball flight, or Play Box, or played his next shot from the drop area. Because he didn’t, he hemorrhaged.

Human skills allow you to counter cortisol buildup by understanding that you need to elevate your DHEA. You can also focus on increasing your reservoirs of DHEA, so you stay on the good side of the grid. But the best way to raise your DHEA when you need to is by creating positive emotions. Remember, these are feelings, rather than thoughts, and they will be unique to each person.

The University of California–Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, which studies the psychology, sociology, and neuroscience of well-being, has published studies indicating that highly effective ways of raising DHEA include summoning feelings of gratitude, humor, or appreciating your natural surroundings. In less stressful situations than disaster during a final tournament round, former PGA Tour player Arron Oberholser raised his DHEA by becoming present to the natural beauty around him on the golf course—the trees, flowers, and mountains. During a tournament round, 2016 U.S. Women’s Open champion Brittany Lang makes a point to think about things she’s grateful for, such as her husband and her dog. (This is essentially why we carry around photos of our friends and family in our wallets. They invoke feelings of love and gratitude.)

Building DHEA is building emotional resilience. Building emotional resilience is a human skill. It’s putting another club in your bag. You’re creating a protective force field. Negative things happen on the golf course. When they do, how do you recognize what’s happening, and how can you limit cortisol and increase DHEA? Even better, how do you preemptively build emotional resilience?

For Russell, an emotional-resilience strategy on the 17th hole might have looked like this: He would have been aware that his cortisol and adrenaline would spike after hitting a shot into the water. He would have understood he needed to lower them, so he could have taken several deep breaths to bring down his adrenaline, and he could have recalled the hundreds of good shots he’d hit on that hole to create positive feelings. He would have chosen a Play Box sensory feel, and the shot easiest to execute at that moment (that is, his best, deepest Play Box feel, and a conservative and dependable “go-to” shot). He might have made sure to hit with 70-percent tempo all the way to the finish of his swing, knowing his adrenaline was sky high. And he would have aimed for the widest part of the green.

Pia likes to use herself as an example to illustrate diagnosis and strategy. “I play my best when I have lower-to-medium adrenaline and some DHEA,” she says. “On the way to the course, I listen to music I love in order to build my DHEA. Before warming up, I meditate for a few minutes to access calmness. During my warm-up, I can tend to go into the future and begin to worry, so often I’ll take long, deep breaths to lower my adrenaline (and commit to a few things under my control). I’ll hit shots with slow tempo. I also do my best to stay away from complainers. Then I’m ready.”

There’s an excellent awareness exercise you can practice on the course to keep track of your emotional states. Draw the adrenaline-DHEA-cortisol grid in your yardage book or on your scorecard. Put an X where you play your best golf. Are you playing well when the X is higher or lower on the adrenaline axis? Where do you play your best on the emotional axis? Is it in the upper-left quadrant when your adrenaline and DHEA are high?

Write down the number of the hole you just played on the grid. Place it where your DHEA and adrenaline levels were. In the illustration above, the player is in lower adrenaline and DHEA after the first three holes. Something happens on the fourth hole to spike the player’s adrenaline and cortisol, so she or he will want to lower adrenaline and access a positive feeling before teeing off on hole 5. After the round, look at where your numbers appear on the grid.

These emotional management and resilience skills are ones you can practice continuously during a round. For instance, on the second hole, you hit a couple of great shots and end up with an eagle. Your adrenaline has risen, so what do you need to do before you tee off on the next hole? You need to take some longer exhales to lower your adrenaline. You’re able to do so and par the hole, but on the next hole, play slows down, which really bugs you. You make a double bogey. What do you need to do? Access something that makes you feel happy, calm, or grateful to create more DHEA. We guarantee that if you come off the 18th green with more DHEA in your system than when you started the round, no matter what your score is, you’re now in charge of your game and your body—you’re resilient. If you’re playing a tournament, you’ve got a human skill in your bag that your opponent might not.

Our VISION54 coaches, Kristine Reese and Tiffany Yager, love to tell a story about playing with some of the young male professionals who work in the Scottsdale area. “They’re in their mid-20s, and they work on their swings all the time,” says Kristine. “I don’t spend too much time on my game right now, but we play fun matches with them. They’re cortisol junkies, and we’ll watch them get more and more upset if they don’t like their shots. When we reach the 12th hole, we press our bet.”

Returning to the idea of the explicit and the implicit, great players used to practice these implicit human skills—even if they didn’t quite know what they were. Ben Hogan would drive to the course very slowly. It was his way of getting his state more regulated. Suzann Pettersen used to watch a sports event, or an inspiring movie like Rocky, before a later tee time. Ariya Jutanugarn listens to her favorite music before she tees off.

Think about things in life that affect our golf games. If you’re late to the course and have only five minutes to warm up, the last thing you want to do is hit balls on the practice range. You’re setting yourself up for an anxiety attack and spiking cortisol. If you only have a few minutes, what makes most sense? It would be much better to create positive emotions—do some balance, tempo, and tension exercises, and put yourself in a good state. That’s being mindful instead of mindless.

Emotional resilience, DHEA and cortisol awareness and management, are not skills we generally learn—or can put on autopilot. They’re necessarily subjective. Did I create cortisol with my negative reaction to that three-putt? What can I do to get back some DHEA before I hit my next tee shot? Some rounds will really test us, so it’s important to keep building this bank of emotional resilience. If this is especially important for you, check it before going out to play, and every so often during your round. The long-lasting effect occurs when you start with a lot of DHEA in your system; that is what it is to be emotionally resilient. Don’t wait until the tank is empty.

One crucial finding by researchers has been that it takes humans six to 10 hours of sleep to reestablish baseline levels of DHEA after an upsetting experience. That means if your cortisol spikes sky-high on a hole, or builds up over a few holes, it’s not likely you can restore the balance right away or even during the round. Russell Knox made sure to get a good night’s sleep that Saturday night, which restored his DHEA-cortisol balance. And he was able to play his final round in a positive state.

Dr. Al Petitpas is a sport psychologist whom we worked with at The First Tee for many years. He says the greatest skill an athlete can learn is to “catch themselves in mid-screwup.” That’s being a Master of Variability. That’s emotional resilience. That’s using your human skills. It’s worth many strokes on the golf course.

Russell has become a true believer. Even though he wasn’t able to catch himself “mid-screwup,” he used emotional resilience after his blowup on No. 17 to raise his DHEA levels before he teed off on Sunday morning.

“Everyone wants to be a perfectionist,” he says. “But golf isn’t a game of perfection. It’s about managing your bad shots and your emotions. At this point in my career, I feel like how I manage myself is way more important than my actual shots.”

EMOTIONAL RESILIENCE is among the most important human skills you can develop—on and off the course. We want to accentuate the point that emotional resilience is a skill, not just a concept. It’s a skill you can practice before a round, between shots, and between holes (and between events in your life, too!). Like many golfers, you might tend to be too outcome-dependent in general. External factors annoy you, such as a bad bounce, slow play, or bogeying a hole. Emotional resilience is important because you’re on the course for many hours. Be proactive about your emotional state—not reactive. Build DHEA before you step onto the course, and keep refining it during play.