9. But Pippo Doesn’t Know

____________________

Other days (five, seven, ten?) have blurred together in my memory, which is just as well, since what that left me with was, so to speak, the quintessence of a montage. I put disparate pieces of evidence together, cutting and joining, sometimes according to a natural progression of ideas and emotions, sometimes to create contrast. What resulted was no longer what I had seen and heard in the course of those days, nor what I might have seen and heard as a child: it was a figment, a hypothesis formed at the age of sixty about what I could have thought at ten. Not enough to say, "I know it happened like this," but enough to bring to light, on papyrus pages, what I presumably might have felt back then.

I had returned to the attic, and I was beginning to worry that none of my school things remained when my eyes lit upon a cardboard box, sealed with adhesive tape, on which appeared the words ELEMENTARY AND MIDDLE YAMBO. There was another, labeled ELEMENTARY AND MIDDLE ADA, but I did not need to reactivate my sister’s memory. I had enough to do with my own.

I wanted to avoid another week of high blood pressure. I called Amalia and had her help me carry the box down to my grandfather’s study. Then it occurred to me that I must have been in elementary and middle school between 1937 and 1945, and so I also brought down the boxes labeled WA R, 1940s, and FASCISM.

In the study, I took everything out and arranged it on various shelves. Books from elementary school, history and geography texts from middle school, and lots of notebooks, with my name, year, and class. There were lots of newspapers. Apparently my grandfather, from the war in Ethiopia on, had kept the important issues: the one with the historic speech by Mussolini proclaiming the birth of the Italian Empire, the one from June 10, 1940, with the declaration of war, and so on until the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima and the end of the war. There were also postcards, posters, leaflets, and a few magazines.

I decided to proceed using the historian’s method, subjecting evidence to cross-comparison. That is to say, when I was reading my books and notebooks from fourth grade, 1940-41, I would also browse through the newspapers from the same years and, whenever I could, put songs from those years on the record player.

Because the books of the period were pro-Fascist, I had assumed that the newspapers would be, too. Everyone knows, for example, that Pravda in Stalin’s day didn’t provide the good citizens of the Soviet Union with accurate news. But I was forced to reconsider. As breathlessly propagandistic as the Italian papers could be, still they allowed readers, even in wartime, to figure out what was going on. Across a distance of many years, my grandfather was giving me a great lesson, civic and historiographic at once: You have to know how to read between the lines. And read between the lines he had, underscoring not so much the banner headlines as the inbriefs, the also-noteds, the news one might miss on a first reading. One issue of Corriere della Sera, from January 6-7, 1941, offered this headline: BATTLE ON THE BARDIA FRONT WAGED WITH GREAT FEROCITY. In the middle of the column, the war bulletin (there was one each day, a bureaucratic listing of such things as the number of enemy aircraft shot down) stated coolly that "other strongholds fell after courageous resistance from our troops, who inflicted substantial losses on the adversary." Other strongholds? From the context it was clear that Bardia, in North Africa, had fallen into British hands. In any case, my grandfather had made a note in red ink in the margin, as he had in many issues: "RL, lost B. 40,000 pris." RL apparently meant Radio London, and my grandfather was comparing the Radio London news with the official news. Not only had Bardia been lost, but forty thousand soldiers had been handed over to the enemy. As one can see, the Corriere had not lied, it had merely taken for granted the facts about which it had remained reticent. The same paper, on February 6, ran the headline OUR TROOPS COUNTERATTACK ON NORTHERN FRONT OF EAST AFRICA. What was the northern front of East Africa? Whereas many issues from the previous year, when giving news of our first inroads into Kenya and British Somalia, had provided detailed maps to show where we were victoriously trespassing, that article about the northern front gave no map, yet all you had to do was go look in an atlas to understand that the British had entered Eritrea.

The Corriere of June 7, 1944, ran this triumphant headline over nine columns: GERMAN DEFENSIVE FIREPOWER POUNDS ALLIED FORCES ALONG NORMANDY COAST. Why were the Germans and the Allies fighting on the coast of Normandy? Because June 6 had been the famous D-day, the beginning of the invasion, and the newspaper, which obviously had not had any news of that event on the previous day, was treating it as though it were already understood, except for pointing out that Field Marshal von Rundstedt had certainly not allowed himself to be surprised and that the beach was littered with enemy corpses. No one could say that was not true.

Proceeding methodically, I could have reconstructed the sequence of actual events simply by reading the Fascist press in the right light, as everyone probably had then. I turned on the radio panel, started the record player, and went back. Of course, it was like reliving someone else’s life.

First school notebook. In those days, we were taught before anything else to make strokes, and we moved on to the letters of the alphabet only when we could fill a page with neat rows of straight lines. Training of the hand, the wrist: handwriting counted for something in the days when typewriters were found only in offices. I moved on to The First Grade Reader, "compiled by Miss Maria Zanetti, illustrations by Enrico Pinochi," Library of the State, Year XVI.

On the page of basic diphthongs, after io, ia, aia, and so on, there was Eia! Eia! next to the Fascist emblem. We learned the

alphabet to the sound of "Eia eia alalà!"-as far as I know one of D’Annunzio’s cries. For the letter B there were words like Benito, and a page devoted to Balilla. At that very moment, my radio began belting out a different syllabication: ba- ba- baby come and kiss me. I wonder how I learned the B, seeing that my little Giangio still confuses it with the V, saying things like bery instead of very?

The Balilla Boys and the Sons of the She-Wolf. A page with a boy in uniform: a black shirt and a sort of white bandolier crossed over his chest with an M at the center. "Mario is a man," the text said.

Son of the She-Wolf. It is May 24. Guglielmo is putting on his brand-new uniform, the uniform of the Sons of the She-Wolf. "Daddy, I’m one of Il Duce’s little soldiers, too, aren’t I? Soon I’ll become a Balilla Boy, I’ll carry the standard, I’ll have a musket, and later I’ll become a Vanguard Youth. I want to do the drills, too, just like the real soldiers, I want to be the best of all, I want to earn lots of medals…"

Right after that, a page that resembled the images d’Épinal, except that these uniforms did not belong to Zouaves or French cuirassiers, but rather to the various ranks of Fascist youth.

In order to teach the l-sound, the book offered examples such as bullet, flag, and battle. For six-year-old children. The ones for whom springtime comes a-dancing. Toward the middle of the syllabary, however, I was taught something about the Guardian Angel:

A boy walks along, down the long road, alone, all alone, where will he go? Small is the boy and the country is wide, but an Angel sees him and walks by his side.

Where was the Angel supposed to lead me? To the place where bullets danced? From what I knew, the Conciliation between

the Church and Fascism had been signed some years earlier, and so by this time they were supposed to educate us to become Balilla Boys without forgetting the Angels.

Did I, too, march in uniform through the streets of the city? Did I want to go to Rome and become a hero? The radio at that moment was singing a heroic anthem that evoked the image of a procession of young Blackshirts, but with the next song the view suddenly changed: walking down the road now was a certain Pippo, who had been poorly served by both Mother Nature and his personal tailor, given that he was wearing his shirt over his vest. With Amalia’s dog in mind, I envisioned this wanderer with a downcast expression, lids drooping over two watery eyes, a dim-witted, toothless smile, two disjointed legs and flat feet. And what connection was there between Pippo and Pipetto?

The Pippo in the song wore his shirt over his vest. But the voices on the radio did not say "shirt," but rather "shir-irt" (he wears his overcoat under his jacket / and he wears his shir-irt over his vest). It must have been to make the words fit the music. I had the feeling I had done the same thing but in a different context. I sang Youth of Italy aloud again, as I had the night before, but this time I sang For Benito and Mussolini, Eia Eia Alalà. We never sang For Benito Mussolini, but rather For Benito and Mussolini. That and was clearly euphonic, serving to give extra oomph to Mussolini. For Benito and Mussolini, his shirt over his vest.

But who was walking through the streets of the city, the Balilla Boys or Pippo? And at whom were people laughing? Might the regime have recognized in the figure of Pippo a subtle allusion? Might our popular wisdom have been offering us that almost infantile drivel as consolation for continually having to endure that heroic rhetoric?

My thoughts wandering, I came to a page about the fog. An image: Alberto and his father, two shadows outlined against other shadows, all of them black, the whole crowd silhouetted against a gray sky, from which emerge the profiles, in a slightly darker gray, of city houses. The text informed me that in the fog people look like shadows. Was that what fog was like?

Should not the gray of the sky have enveloped, like milk, or like water and anisette, even the human shadows? According to my collection of quotations, shadows are not outlined against the fog, but are born from it, confused with it-the fog makes shadows appear even where nothing is, and nothing precisely where shadows will emerge… My first-grade reader, then, was lying to me even about the fog? In fact, it concluded with an invocation to the beautiful sun to clear away the fog. Its message was that fog was inevitable, but undesirable. Why did they teach me fog was bad, if later I was to harbor an obscure nostalgia for it?

Gray, black, blackout. Words that call to mind other words. During the war, Gianni had said, the city was plunged into darkness so as not to be visible to enemy bombers, and none of us could

allow even a sliver of light to show through our windows. If that was true, we must have blessed the fog then, as it spread its protective mantle over us. Fog was good.

Of course my first-grade reader could not have had anything to tell me about blackouts, as it had been published in 1937. It spoke only of dreary fog, the kind that climbed the bristling hills. I paged through the books from subsequent years, but found no signs of the war even in the one for fifth grade, though it had been published in 1941 and the war was then a year old. It was still an edition from earlier years, and it mentioned only heroes from the Spanish Civil War and the conquest of Ethiopia. The hardships of war were not a seemly subject for schoolbooks, which avoided the present in favor of celebrating the glories of the past.

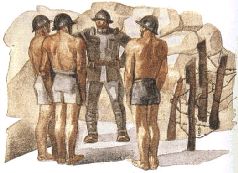

My reader from the fourth grade, 1940-1941 (that autumn we were in the first year of the war), contained only histories of glorious actions from World War I, with pictures that showed our infantrymen standing on the Carso, naked and muscled, like Roman gladiators.

But on other pages there appeared, perhaps to reconcile Balilla Boys with Angels, stories about Christmas Eve that were full of sweetness and light. Since we were to lose all of Italian East Africa only at the end of 1941, by which time that book was already making the rounds in schools, our proud colonial troops were still featured, and I was struck by a Somali Dubat in his handsome, characteristic uniform, which had been adapted from the style of dress of those natives we were civilizing: he was bare-chested except for a white sash knotted to his ammo belt. The caption was pure poetry: The legionary Eagle spreads its wings-over the world: only the Lord shall stop it. But Somaliland had already fallen into English hands by February, perhaps even as I was first reading that page. Did I know it at the time?

In any case, in that same syllabary I was also reading The Basket recycled: Goodbye to the thunder blast! / Goodbye to the stormy day! / The clouds have run away / and the sky is clean at last… / The world, consoled, grows calm, / and on each afflicted thing, / quiet and comforting, / peace settles like a balm.

And what about the war in progress? My fifth-grade reader included a meditation on racial differences, with a section on the Jews and the attention that should be paid to this untrustworthy breed, who "having shrewdly infiltrated Aryan regions… introduced among the Nordic peoples a new spirit made up of mercantilism and profit hunger." I also found in those boxes various issues of Defense of the Race, a magazine founded in 1938. (I do not know whether my grandfather ever allowed it to fall into my hands, but I suspect I poked my nose into everything sooner or later.) They contained photos that compared aborigines to an ape and others that revealed the monstrous consequences of crossing a Chinese with a European (such degenerate phenomena, however, apparently occurred only in France). They spoke highly of the Japanese race and pointed out the unmistakable stigmata of the English race-women with double chins, ruddy gentlemen with alcoholic noses-and one cartoon showed a woman wearing a British helmet, immodestly covered with nothing but a few pages of the Times arranged like a tutu: she was looking in the mirror, and TIMES, backwards, appeared as SEMIT. As for actual Jews, there was little to choose from: a survey of hooked noses and unkempt beards, of piggy, sensual mouths with buckteeth, of brachycephalic skulls and scarred cheekbones and wretched Judas eyes, of the unchecked guts of well-dressed profiteers, their gold fobs dangling from their watch pockets and their greedy hands poised above the riches of the proletarian masses.

My grandfather, presumably, had inserted among those pages a propaganda postcard showing a repugnant Jew, with the Statue of Liberty in the background, thrusting his fists toward the viewer. And there was something for everyone: another postcard showed a grotesque, drunken Negro in a cowboy hat clutching a big, clawlike hand around the white midriff of the Venus de Milo. The artist had apparently forgotten that we had also declared war on Greece, so why should we have cared if that brute was groping a mutilated Greek woman, whose husband went around in a kilt with pompoms on his shoes?

For contrast, the magazine showed the pure, virile profiles of the Italic race, and when it came to Dante and a few of our leaders whose noses were not exactly small or straight, they spoke in terms of the "aquiline race." In case the appeal to uphold the Aryan purity of my countrymen had not completely convinced me, my school-book contained a fine poem about Il Duce (Square is his chin, his chest is squarer yet, / His footstep that of a pillar walking, / His voice as biting as a fountain’s jet) and a comparison of the masculine features of Julius Caesar with those of Mussolini (I would learn only later, from encyclopedias, that Caesar used to go to bed with his legionnaires).

Italians were all beautiful. Beautiful Mussolini himself, who appeared on the cover of Tempo, an illustrated weekly, on horseback, sword raised high (an actual photo, not some artist’s allegorical invention-does that mean he went around carrying a sword?) to celebrate our entry into the war; beautiful the blackshirt proclaiming things like HATE THE ENEMY and WE WILL WIN!; beautiful the Roman swords stretching toward the outline of Great Britain;

beautiful the rustic hand turning up its thumb as London burned; beautiful the proud legionnaire outlined against the backdrop of the ruins of Amba Alagi, promising WE WILL RETURN!

Optimism. My radio continued to sing Oh he was big but he wasn’t tall, they called him Bombolo, he danced a jig then started to fall and tumbled head over toe, he tumbled here, he tumbled there, he bounced like a rubber ball, his luck was gone, he fell in a pond, but he floated after all.

But beautiful above all else were the images, in magazines and publicity posters, of pure-blooded Italian girls, with their large breasts and soft curves, splendid baby-making machines in contrast to those bony, anorexic English misses and to the "crisis woman" of our own plutocratic past. Beautiful the young ladies who seemed to be actively competing in the "Five Thousand Lire for a Smile" contest, and beautiful also that provocative woman, her rear well defined by a seductive skirt, who strode across a publicity poster as the radio assured me that dark eyes might be pretty, blue eyes might be swell, but as for me, oh as for me, it’s their legs that I like well.

Utterly beautiful the girls in all the songs, whether they were rural, Italic beauties ("the buxom country girls") or urban beauties like the "lovely piccinina," that milliner’s assistant from Milan with her delicate half-powdered face, walking through crowds at a bustling pace… Or beauties on bikes, symbols of a brash, disheveled femininity, with legs so slim, so shapely and trim.

Ugly, of course, were our enemies, and several copies of Balilla, the weekly for the Italian Fascist Youth, contained illustrations by De Seta alongside stories that made fun of the enemy, always through brutish caricatures: The war had him worried / so King Georgie scurried / for defense from things sinister / to Big Winston, his Minister-and then there were the other two villains, Big Bad Roosevelt and the terrible Stalin, the red ogre of the Kremlin.

The English were bad because they used the equivalent of Lei, whereas good Italians were supposed to use, even when addressing people they knew, nothing but the oh-so-Italian Vo i. A basic knowledge of foreign languages suggests that it is the English and French who use Vo i (you, vous), whereas Lei is very Italian, though perhaps influenced by Spanish, and at the time we were thick as thieves with Franco’s Spain. As for the German Sie, it is a Lei or a Low, but not a Vo i. In any case, perhaps as a result of poor knowledge of things foreign, Lei as the polite form of you had been rejected by the higher powers in favor of Vo i -my grandfather had kept clippings that were quite explicit and rather inflexible on the matter. He had also had the presence of mind to save the last issue of a women’s magazine called Lei, in which it was announced that beginning with the next issue it would be called Annabella. Obviously, the Lei in this context was not an address to "you," the magazine’s ideal reader, but rather an instance of the pronoun "she," indicating that the magazine was aimed at women, not men. But regardless, the word Lei, even when serving a different grammatical function, had become taboo. I wondered if the whole episode had made the women who read the magazine laugh at the time, and yet it had happened and everyone had put up with it.

And then there were the colonial beauties, because even though Negroid types resembled apes and Abyssinians were plagued by a whole host of maladies, an exception had been made for the beautiful Abyssinian woman. The radio sang: Little black face / sweet Abyssinian / just wait and pray / we’re nearing our dominion / Then we’ll be with you / and gifts we’ll bring / yes we will give you / a new law and a new King.

Just what should be done with the beautiful Abyssinian woman was made clear in De Seta’s color cartoons, which featured Italian legionnaires buying half-naked, dark-skinned females in slave markets and sending them to their pals back home, as parcels.

But the feminine charms of Ethiopia had been evoked from the very beginning of the colonial campaign in a nostalgic caravan-style song: They’re off / the caravans of Tigrai / toward a star that by and by / will shine and glimmer with love.

And I, caught in this vortex of optimism, what had I thought? My elementary-school notebooks held the answer. It was enough to look at their covers, which immediately invited thoughts of daring and triumph. Except for a few that contained thick, white paper (they must have been more expensive) and bore on their covers the portraits of Great Men (I must have done some woolgathering around the name and the enigmatic, smiling face of a gentleman called Shakespeare-which I no doubt pronounced as it was spelled, with four syllables-seeing that I had gone over all the letters in pen, as if to interrogate or memorize them), the notebooks boasted images of Il Duce on horseback, of heroic combatants in black shirts lobbing hand grenades at the enemy, of slender PT boats sinking enormous battleships, of couriers with a sublime sense of sacrifice, who though their hands have been mangled by a grenade run on beneath the crackle of enemy machine guns, carrying their messages between their teeth.

Our headmaster (why headmaster and not headmistress? I do not know, but I could hear myself saying "Mr. Headmaster") had dictated to us the key passages from Mussolini’s historic address on the day he declared war, June 10, 1940, inserting, following the newspaper accounts, the reactions of the oceanic audience listening to him in Piazza Venezia:

Combatants on land, at sea, and in the air! Blackshirts of the revolution and of the legions! Men and women of Italy, of the Empire and of the kingdom of Albania! Listen! An hour signaled by destiny is striking in the skies of our fatherland. The hour of irrevocable decisions. The declaration of war has already been delivered (cheering, deafening cries of "War! War!") to the ambassadors of Great Britain and of France. We are going to battle against the plutocratic and reactionary democracies of the West, who at every turn have hindered the advance and often threatened the very existence of the Italian people…

According to the laws of Fascist morality, when one has a friend one marches with him wholeheartedly. (Shouts of "Duce! Duce! Duce!") This is what we have done and will do with Germany, with her people, with her marvelous armed forces. On the eve of this event of historic import, we turn our thoughts to his Majesty the Emperor King (the multitudes erupt in great cheers at the mention of the House of Savoy), who, as always, has understood the spirit of the fatherland. And we salute the Führer, the head of allied Greater Germany. (The crowd cheers at length at the mention of Hitler.) Italy, proletarian and Fascist, is on her feet for the third time, strong, proud, and united as never before. (The multitude cries out in a single voice: "Yes!") The watchword is one word only, categorical and binding for all. It has already taken wing, stirring hearts from the Alps to the Indian Ocean: Victory! And we will win! (The crowd erupts in deafening cheers.)

It was in those months that the radio must have begun playing "Victory," echoing the word of the Chief:

Steeled by a thousand passions, the voice of our nation rang clear! "Centuries, Cohorts, and Legions, attention, the hour is here!" March onward, young men!

Who holds us back

or blocks our track,

we’ll knock them aside!

Slaves never again!

Our hands won’t be tied

like prisoners by our own sea!

Victory, victory, victory!

We will triumph in the air, on land, at sea!

The highest powers say

it’s the watchword of the day:

Victory, victory, victory!

At any cost: nothing will stand in our way!

Our hearts are eager to obey

even to our last breath.

And our voices swear today:

Victory or death!

How might I have experienced the beginning of a war? As a great adventure, undertaken at the side of my German comrade. His name was Richard, as the radio informed me in 1941: Comrade Richard, welcome … I learned how I, in those glorious years, might have imagined my comrade Richard (the song’s rhythm obliged us to pronounce that name like the French Richard, rather than the German Richard) from a postcard, on which he appeared alongside an Italian comrade, both in profile, both masculine and decisive, their gaze fixed on the finish line of victory.

But my radio, after "Comrade Richard," was already playing (by this point I was convinced it was a live broadcast) a different song. This one was in German, a sad dirge, almost a funeral march that seemed to me to keep time with some imperceptible rhythm in my gut, sung by a woman whose voice was deep and hoarse, mournful and sinful: Vo r d e r Kaserne / Vor dem großen Tor / Stand eine Laterne / Und steht sie noch davor…

My grandfather had owned the record, but in those days I would not have understood the German.

And indeed I listened next to the Italian version, which was more a paraphrase or an adaptation than a translation:

Every evening

beneath the streetlamp’s glow

not far from the garrison

I waited for you to show.

I’ll be there this evening too,

forgetting all the world with you,

with you, Lili Marleen,

with you, Lili Marleen.

When I must walk through the muck and mire beneath my heavy pack I feel unsure and tired.

Where will I go? What will I do? Then I smile and think of you, of you, Lili Marleen, of you, Lili Marleen.

Though the Italian lyrics fail to say so, in the German the streetlamp emerges from the fog: Wenn sich die späten Nebel drehn, when the late fog swirls. But in any case, in those days I would not have understood that the sad voice in the fog beneath that streetlamp (my concern then was probably how a streetlamp could have been lit during a blackout) belonged to the mysterious pitana, "the woman who sells by herself." That song must be why, years later, I took note of this passage from Corazzini’s poem "The Streetlamp": Murky and scant in the lonely thoroughfare, / in front of the bordello doors, it dims, / and the good smoke that from the censer swims / might be this fog that whitens out the air.

"Lili Marleen" came out not too long after the giddy "Comrade Richard." Either we were generally more optimistic than the Germans, or in the interim something had happened, our poor comrade had grown sad and, tired of walking through muck, longed to go back to his streetlamp. But I was coming to realize that the same series of propagandistic songs could explain how we had gone from a dream of victory to one of the welcoming bosom of a whore as hopeless as her clients.

After our initial enthusiasm, we grew accustomed not only to blackouts and, I imagine, to bombings, but also to hunger. Why else would it have been necessary to encourage the little Balilla Boy, in 1941, to cultivate a war garden on his apartment balcony, if not so that he could squeeze a few vegetables from the most paltry of spaces? And why has the boy received no news from his father at the front?

Dear Papà, my hand is shaking some, but you will understand what I am saying. It’s been so many days since you left home

and yet you haven’t told me where you’re staying.

As for the tears that trickle down my cheek,

you can be sure they’re only tears of pride.

I still can see you smile and hear you speak,

and your Balilla waits for you, arms wide.

I’m helping in the war, I’m fighting, too,

with discipline, with honor, and with faith.

I want this land of mine to bear good fruit,

so I tend my little garden every day

(my own war garden!) and ask God each night

to watch you, to make sure my dad’s all right.

Carrots for victory. By contrast, in one of my notebooks I found a place where the headmaster had made us take note of the fact that our English enemies were a five-meal people. I must have thought to myself that I had five meals, too: coffee with bread and marmalade, a snack at ten at school, lunch, an afternoon snack, then dinner. But perhaps other children were not as fortunate, and a people who ate five meals a day could not but stir resentment among those who had to grow tomatoes on their balcony.

But then why were the English so skinny? And why did one of my grandfather’s postcards feature (above the word Hush!) a crafty Englishman trying to overhear military secrets that some loose-lipped Italian comrade might let slip in some bar? How was such a thing possible if the entire population had rushed as one to take up arms? Were there Italians who spied? Had the subversives not been defeated, as the stories in my reader explained, by Il Duce with his march on Rome?

Various pages of my notebooks mentioned the now imminent victory. But as I was reading, a beautiful song dropped onto the turntable. It told the story of the last stand of Giarabub, one of our desert strongholds, where the exploits of our besieged soldiers, who finally succumbed to hunger and lack of munitions, attained epic dimensions. In Milan some weeks earlier, I had seen on television a

color movie about the last stand of Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie at the Alamo. Nothing is more exhilarating than the topos of the besieged fort. I imagine I once sang that sad elegy with the emotion of a boy watching a Western today.

I sang that England’s final stand had begun at Giarabub, but the song must have reminded me of Maramao, Why Did You Die, because it was the celebration of a defeat-my grandfather’s newspapers told me more: the Giarabub oasis in Cyrenaica had fallen, despite heroic resistance, in March of 1941. Using a defeat to electrify a population seemed to me a rather desperate measure.

And this other song, from the same year, that promised victory? "Blue Skies Are on the Way!" promised blue skies by April-by which time we were to lose Addis Ababa. In any case, people say "blue skies are on the way" when the weather is bad and they hope it will change. Why were blue skies supposed to be coming (in April)? A sign that during the winter, when the song was first sung, people had been looking forward to a reversal of fortune.

All the heroic propaganda we were raised on alluded to some frustration. What did the refrain "We will return" mean, if not that we looked forward to, hoped for, counted on a return to the place where we had been defeated?

And when did "The M Battalions" anthem come out?

Battalions of Il Duce, battalions of death created in life’s name, in the springtime begins the game, the continents will flame and flower! We’ll win with Mussolini’s Lions, made strong by his courageous power.

These battalions of death they are life battalions, too, there is no love without hate, so the game begins anew.

The M we wear is red like fate, our tassels black, and as for death we’ve faced it with grenades in hand and a flower between our teeth.

According to my grandfather’s dates, it must have come out in ’43, and once again, two years after Giarabub, springtime was invoked (we signed the armistice in September of ’43). Leaving aside the image, which must have fascinated me, of greeting death with grenades in hand and a flower between our teeth, why did the game have to begin again in springtime, why did it have to start over? Had it been stopped? And yet they had us singing it, in a spirit of incorruptible faith in final victory.

The only optimistic anthem that the radio offered me was the "Song of the Submariners": to creep through the ocean deep, laughing in the face of Lady Death and Fate… But those words reminded me of others, and I went looking for a song called "Young Ladies, Keep Your Eyes Off Sailor Boys."

They would not have had me sing this at school. Apparently it was played on the radio. The radio, then, played both the submariner’s song and the warning to young ladies. Two worlds.

The other songs, too, made it seem as if life were running on two different tracks: on one, the war bulletins; on the other, the endless lessons in optimism and gaiety that our orchestras offered in such abundance. Was war breaking out in Spain, with Italians dying on both sides, while our Chief passionately exhorted us to prepare for a larger, bloodier conflict? Luciana Dolliver sang (such an exquisite flame) don’t forget my words, my darling one, you don’t know what love is, the Barzizza Orchestra played oh baby how I love you, I’ve been dreaming of you, you slept, I stood above you, you smiled then in your sleep, and everyone was repeating Fiorin, Fiorello, l’amore è bello when you’re by my side. Was the regime celebrating beautiful country girls and productive mothers by imposing

a bachelor tax? The radio gave notice that jealousy had gone out of fashion, that it had become uncouth.

Was war breaking out, and did we have to darken our windows and stay glued to the radio? Alberto Rabagliati whispered that we should turn the volume way down low to hear his heart beat through the radio. Had our campaign to "break the back of Greece" got off to a bad start, and had our troops begun dying in the mud? No worries, one does not make love when rain is falling.

Did Pippo really not know? How many souls did the regime have? The battle of El Alamein was raging beneath the African sun, and the radio was intoning that’s how I want to live, sun on my face, singing happily, full of bliss. We were going to war against the United States and our papers were celebrating the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, and the airwaves were bringing us beneath Hawaiian skies you’ll watch the full moon rise and dream of paradise. (But perhaps the listening audience was not aware that Pearl Harbor was in Hawaii or that Hawaii was a U.S. territory.) Field Marshal Paulus was surrendering in Stalingrad amid stacks of bodies from both sides, and we were hearing I have a pebble in my shoe, and oh it’s really killing me.

Allied troops were landing in Sicily, and the radio (in the voice of Alida Valli!) was reminding us that love is not that way, love won’t turn to gray the way the gold fades in a woman’s hair. Rome was experiencing its first air raids, and Jone Caciagli was twittering night and day, hand in hand, you and I away from everyone, till the rising of tomorrow’s sun.

The allies were landing at Anzio and the radio could not get enough of "Bésame, Bésame Mucho"; the Fosse Ardeatine massacre took place, and the radio kept our spirits high with "Baldy" and "Where Is Zazà Now"; Milan was being tortured with bombardments, and Radio Milan was broadcasting "The Dandy-Girl of the Biffi Scala"…

And what about me, how did I experience this schizophrenic Italy? Did I believe in victory, did I love Il Duce, did I want to die for him? Did I believe in the Chief’s historic phrases, which the headmaster dictated to us: It’s the plow that makes the furrow but it’s the sword that defends it; We will not back down; If I advance, follow, if I retreat, kill me?

In a notebook from fifth grade, 1942, Year XX of the Fascist Era, I found one of my in-class compositions:

Topic: "O children, you must remain for the rest of your lives the guardians of the new heroic civilization that Italy is creating." (Mussolini)

Treatment: Here along the dusty road a column of young boys advances.

They are the Balilla Boys, proud and robust beneath the mild sun of early spring, marching with discipline, obeying the terse commands imparted by their officers; it is those boys who at twenty years of age will set aside their pens in order to take up muskets to defend Italy against its insidious enemies. Those Balilla Boys who can be seen marching through the streets on Saturdays and hunching over their school desks studying on other days, will at the proper age become faithful and incorruptible guardians of Italy and its civilization.

Who would have imagined, watching the legions parading by during the "Youth March," that those beardless boys, many still Vanguard Youths at that time, would already have reddened the burning sands of Marmarica with their blood? Who imagines, seeing these boys now, cheerful and always in a joking mood, that within a few years they, too, may die on the battlefield with the name of Italy on their lips?

My insistent thought has always been this: when I grow up, I will be a soldier. And now that I hear on the radio about the countless deeds of courage, heroism, and self-denial performed by our brave soldiers, my desire has become even more deeply anchored in my heart, and no human force could uproot it.

Yes! I will be a soldier, I will fight and, if it is Italy’s will, die for the new, heroic, holy civilization, which will bring well-being to the world and which God desired should be built by Italy.

Yes! The happy, playful Balilla Boys will become lions when they grow up should any enemy dare to profane our holy civilization. They would fight like wild beasts, fall and get back up to fight again, and they would triumph, bringing another victory to Italy, immortal Italy.

And with the guiding memory of past glories, with the results of present glories, and with the hope for future glories to be brought home by the Balilla Boys, youths today but soldiers tomorrow, Italy will continue its glorious path toward winged victory.

Did I really believe all that, or was I repeating stock phrases? What did my parents think when I brought home (with high marks) such compositions? Perhaps they believed it themselves, having absorbed phrases of the kind even prior to Fascism. Had they not, as is commonly known, been born and grown up in a nationalistic climate in which the First World War was celebrated as a purifying bath? Had the futurists not said that war was the world’s only hygiene? Among the books in the attic, I had come across an old copy of Heart, the famous late nineteenth-century children’s book by De Amicis, in whose pages, among the heroic deeds of the Little Paduan Patriot and the magnanimous acts of Garrone, I found this passage, in which Enrico’s father writes to his son in praise of the Royal Army:

All these young people full of strength and hope may from one day to the next be called upon to defend our Nation and within a few hours be smashed by bullets and grapeshot. Every time you hear someone at a festival shout, "Long live the Army, long live Italy," I want you to picture, beyond the passing regiments, a field covered with corpses and flooded with their blood, and then your hurrahs for the army will spring from deeper in your heart, and your image of Italy will be more severe and grand.

So it was not only myself, but my elders, too, who had been raised to conceive of love for our country as a blood tribute, and to feel not horror but excitement when faced with a landscape flooded with blood. For that matter, had not the great Leopardi himself, gentlest of poets, written a hundred years earlier: O providential, dear, and hallowed were / the days of old when for their fatherland / the people ran in squads to die?

I understood that even the massacres in the Illustrated Journal of Voyages and Adventures must not have seemed exotic to me at all, since I had been raised in a cult of horror. And it was not simply an Italian cult, for in that same Illustrated Journal I had read other encomiums to war and to redemption through bloodbaths uttered by heroic French poilus, who had turned the Sedan debacle into their own rabid, vengeful myth, as we were to do with Giarabub. Nothing is more likely to incite a holocaust than the rancor of a defeat. That was how we, fathers and sons, were taught to live, through stories of how beautiful it was to die.

But how much did I really want to die and what did I know of death? In my fifth-grade reader, I found a story called "Loma Valente." Its pages were more tattered than the rest, the title had been marked in pencil with a cross, many passages were underlined. The story describes a heroic episode from the Spanish Civil War, involving a battalion of Black Arrows emplaced below a harsh, rugged hilltop (loma in Spanish) that offers little opening for an attack. But one platoon is commanded by a dark-haired athlete, twenty-four years of age, named Valente, who back home in Italy studied literature and wrote poetry, though he also won the boxing prize at the Fascist Games. Valente, who has volunteered in Spain, where "pugilists and poets both had something to fight for," orders the attack fully aware of the risks, and the story treats the various phases of the gallant undertaking: the Reds ("Damn them, where are they? Why won’t they show themselves?") fire every weapon they have, a torrent, "as if throwing water on a wildfire that was spreading and coming closer." Valente has only a few steps left to conquer the hill, when a sudden, sharp blow to his head fills his ears with a terrible din:

Then, darkness. Valente’s face lies in the grass. The darkness now grows less black; it is red. The eye of our hero that lies closest to the ground sees two or three blades of grass as thick as stakes.

A soldier comes up to him and whispers that the hill has been taken. The author now speaks for Valente: "What does it mean to die? It is the word, usually, that is frightening. Now that he is dying, and knows it, he feels neither heat, nor cold, nor pain." He knows only that he has done his duty and that the loma he has conquered will bear his name.

I understood from the tremor that accompanied my adult rereading of those few pages that they had offered me my first vision of actual death. That image of blades of grass as thick as stakes seemed to have inhabited my mind from time immemorial, I could almost see them as I was reading. Indeed I had the feeling that as a child I had often repeated, as a sacred rite, a descent into the garden, where I would lie prone, my face flattened against some patch of redolent grass, in order to really see those stakes. That reading had been the fall on the road to Damascus that had marked me, perhaps, forever. It was during those same months that I had written the composition that now so disturbed me. Was such duplicity possible? Or had I read the story after writing the composition, and had everything changed from that moment?

I had come to the end of my elementary school years, which concluded with the death of Valente. The middle-school books were less interesting-Fascist or not, if your subject is the seven kings of Rome or polynomials, you have to say more or less the same things. But among my middle-school materials were notebooks called "Chronicles." Some kind of curriculum reform had taken place, and we were no longer assigned compositions on fixed topics, but were apparently encouraged to recount episodes from our lives. And we had a different teacher, who read all the chronicles and marked them in red pencil, not with a grade but with a critical comment regarding their style or inventiveness. It was clear from the feminine endings of certain words in those comments that the teacher was a woman. Clearly an intelligent woman (perhaps we adored her, because reading those red messages I sensed that she must have been young and pretty and, God knows why, very fond of lilies of the valley), who had tried to push us to be sincere and original.

One of my most highly praised chronicles was the following, dated December 1942. I was eleven by then, but only nine months had passed since the earlier composition.

Chronicle: The Unbreakable Glass

Mother had purchased an unbreakable glass. But it was actual glass, real glass, and I was dumbfounded, because when this event took place, the undersigned was only a few years old, and his mental faculties were not yet so well developed that he could imagine that a glass, a glass similar to the ones that went crash! when they fell (leading to a good cuffing) could be unbreakable.

Unbreakable! It seemed like a magic word. The boy tries it once, twice, three times, and each time the glass falls, bounces with a terrible racket, and remains intact.

One evening some family friends come by and chocolates are passed around (note that back then those delicacies still existed, and in great number). With my mouth full (I no longer recall the brand, Gianduia or Strelio or Caffarel-Prochet), I proceed to the kitchen and return with the famous glass.

"Ladies and gentlemen," I exclaim, with the voice of a ringmaster calling out to passersby to attend the show, "I present to you a unique, magic, unbreakable glass. I will now throw it to the ground and you will see that it will not break," and in a grave and solemn manner I add, "IT WILL REMAIN INTACT."

I throw it, and… needless to say, the glass shatters into a thousand pieces.

I feel myself turn red, I stare in shock at those shards that, struck by the light of the chandelier, are gleaming like pearls… and I burst into tears.

End of my story. Now I was trying to analyze it as though it were a classic text. I was writing about a pretechnological society, in which an unbreakable glass was a rarity, and people would purchase a single glass to try it out. Breaking it was not only a humiliation, but also a blow to the family finances. It was thus a story of defeat on all fronts.

My story, from 1942, evoked the prewar period as a happier era, when chocolates were still available, and foreign brands at that, when people received guests in their living rooms or in their dining rooms beneath a bright chandelier. The appeal I had made to my audience had not resembled Il Duce’s appeals from the balcony of Palazzo Venezia, but had rather the ridiculous air of the barkers I may have heard at the market. I was evoking a gamble, an attempted triumph, an incorruptible certainty, and then, with a nice anticlimax, I reversed the situation and recognized that I had lost.

It was one of the first stories that was truly mine, not the repetition of schoolboy clichés nor the rehashing of some adventure novel. The drama of a promissory note not made good. In those shards that, lit by the chandelier, gleamed (falsely) like pearls, I was celebrating at the age of eleven my own vanitas vanitatum and professing a cosmic pessimism.

I had become the narrator of a failure, whose breakable objective correlative I represented. I had become existentially, if ironically, bitter, radically skeptical, impervious to all illusion.

How can a person change so much in the course of nine months? Natural growth, no doubt, one gets cleverer with age, but there was more: the disillusionment caused by broken promises of glory (perhaps I, too, still in the city then, was reading the newspapers my grandfather had underlined), and my encounter with the death of Valente, whose heroic act had resolved into that terrible image of rot-green stakes, the final fence separating me from the underworld and the fulfillment of every mortal’s natural fate.

In nine months I had become wise, with a sarcastic, disenchanted wisdom.

And what of everything else: the songs, Il Duce’s speeches, the oh-babys, and the idea of facing death with grenades in hand and a flower between our teeth? Judging by the headings in my notebooks, I spent the first year of middle school, during which I had written that chronicle, still in the city, then the next two years in Solara. Meaning that my family had decided to evacuate definitively to the country, because the first bombardments had finally reached our city. I had become a citizen of Solara in the wake of my remembrance of that broken glass, and my remaining chronicles, from the second and third years of middle school, were all remembrances of better, bygone times, when if you heard a siren you knew it came from the factory and you said to yourself, "It’s noon, father will be home soon," stories about how great it would be to return to a peaceful city, reveries about the Christmasses of yesteryear. I had taken off my Balilla Boy uniform and had become a little decadent, devoted already to the search for lost times.

And how had I spent the years from 1943 to the end of the war, the darkest years, with the Partisan struggle and the Germans no longer our comrades? Nothing in the notebooks, as if speaking of the horrid present had been taboo and our teachers had encouraged us not to do it.

I was still missing some link, perhaps many links. At some point I had changed, but I did not know why.