6. Il Nuovissimo Melzi

____________________

I went down into the village. The hike back was a strain, but it was a lovely walk, and invigorating. Good thing I brought a few cartons of Gitanes with me, because here they carry only Marlboro Lights. Country people.

I told Amalia about the barn owl. She was not amused when I said I had taken it for a ghost. She looked serious: "Barn owls, no, good critters that never hurt a body. But over yonder," and she gestured toward the slopes of the Langhe hills, "yonder they’ve still got hellcats. What’s a hellcat? I’m almost afraid to say, and you should know, seems like my poor old pa was always telling you some story or other about them. Don’t worry, they don’t come up here, they stick to scaring ignorant farmers, not gentlemen who just might know the right word to send them running off. Hellcats are wicked women who traipse around at night. And if it’s foggy or stormy, all the better, then they’re happy as clams."

That was all she would say, but she had mentioned the fog, so I asked her if we got much of it here.

"Much of it? Jesus and Mary, too much. Some days I can’t see the edge of the driveway from my door-but what am I saying, I can’t even see the front of the house from here, and if someone’s home at night you can just make out the light ever so faint coming from the window, but like it was just a candle. And even when the fog doesn’t quite reach us, you should see the sight toward the hills. Maybe you can’t see a thing for a ways, and then something pokes up-a peak, a little church-and then just white again after. Like somebody down there had knocked over the milk pail. If you’re still around come September, you can bet you’ll see it yourself, because in these parts, except for June to August, it’s always foggy. Down in the village there’s Salvatore, a fellow from Naples who fetched up here twenty years ago looking for work, you know how bad things are down south, and he’s still not used to the fog, says that down there the weather’s nice even for Epiphany. You wouldn’t believe how many times he got lost in them fields and almost fell into the torrent and folks had to go find him in the dark with flashlights. Well, his kind might be decent folk, I can’t say, but they’re not like us."

I recited silently to myself:

And I looked toward the valley: it was gone, utterly vanished! A vast flat sea remained, gray, without waves or beaches; all was one. And here and there I noticed, when I strained, the alien clamoring of small, wild voices: birds that had lost their way in that vain land. And high above, the skeletons of beeches as if suspended in the sky, and dreams of ruins and the hermit’s hidden reaches.

But for now, the ruins and hermitages I was seeking, if they existed, were right there in broad daylight, yet no less invisible, for the fog was within me. Or perhaps I should be looking for them in the shadows? The moment had come. I had to enter the central wing.

When I told Amalia that I wanted to go alone, she shook her head and gave me the keys. There were a lot of rooms, it seemed, and Amalia kept them all locked, because you never knew when there might be a ne’er-do-well about. She gave me a bunch of keys, large and small, some of them rusty, telling me that she knew them all by heart, and if I really wanted to go on my own I would just have to try each key in each door. As if to say, "Serves you right, you’re just as headstrong now as when you were little."

Amalia must have been up there in the early morning. The shutters, which had been closed the day before, were now partly open, just enough to let light into the corridors and rooms so you could see where you were going. Despite the fact that Amalia came from time to time to air the place out, there was a musty smell. It was not bad, it simply seemed to have been exuded by the antique furniture, the ceiling beams, the white fabric draped over the armchairs (shouldn’t Lenin have been sitting there?).

Never mind the adventure, the trying and retrying of the keys, that made me feel like the head jailer at Alcatraz. The stairway led up into a room, a sort of well-furnished antechamber, with those Lenin chairs and some horrible landscapes, oils in the style of the nineteenth century, nicely framed on the walls. I had yet to get a sense of my grandfather’s tastes, but Paola had described him as a curious collector: he could not have loved those daubs. They must have been in the family, then, maybe the painting exercises of some great-grandparent. That said, in the penumbra of that room they were barely noticeable-dark blotches on the walls-and maybe it was right that they were there.

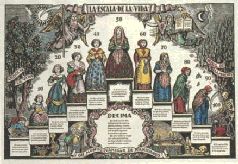

That room led at one end onto the façade’s only balcony and at the other into the midpoint of a long hallway, wide and shadowy, that ran along the back of the house, its walls almost completely covered in old color prints. Turning right, one encountered pieces from the Imagerie d’Épinal that depicted historical events: "Bombardement d’Alexandrie," "Siège et bombardement de Paris par les Prussiens," "Les grandes journées de la Révolution Française," "Prise de Pékin par les Alliées." And others were Spanish: a series of little monstrous creatures called "Los Orrelis," a "Colección de monos filarmónicos," a "Mundo al revés," and two of those allegorical stairways, one for men and another for women, that depict the various stages of life-the cradle and babies with leading strings on the first step; then, step by step, the approach to adulthood, which is represented by beautiful, radiant figures atop an Olympic podium; from there, the slow descent of increasingly elderly figures, who by the bottom step are reduced, as the Sphinx described, to three-legged creatures, two wobbly sticks and a cane, with an image of Death awaiting them.

The first door on the right opened into a vast old-style kitchen, with a large stove and an immense fireplace with a copper cauldron still hanging in it. All the furnishings were from times past, maybe going back to the days of my grandfather’s great-uncle. It was all antique by now. Through the transparent panes of the credenza I could see flowered plates, coffeepots, coffee cups. Instinctively I looked for a newspaper rack, so I must have known there was one. I found it hanging in a corner by the window, in pyrographed wood, with great flaming poppies etched against a yellow background. During the war, when there were shortages of firewood and coal, the kitchen must have been the only heated place, and who knows how many evenings I had spent in that room…

Next came the bathroom, also old-fashioned, with an enormous metal tub and curved faucets that looked like drinking fountains. And the sink looked like a font for holy water. I tried to turn on the taps, and after a series of hiccups some yellow stuff came out of them that began to clear only after two minutes. The toilet bowl and flusher called to mind the Royal Baths of the late nineteenth century.

Past the bathroom, the last door opened into a bedroom that contained a few small items of furniture, in pale green wood decorated with butterflies, and a small single bed. Propped against the pillow sat a Lenci doll, mawkish as only a cloth doll from the thirties can be. This was no doubt my sister’s room, as several little dresses in a drawer confirmed, but it seemed to have been stripped of every other furnishing and closed up for good. It smelled of damp.

Past Ada’s room, at the end of the hall, stood an armoire, which I opened: it still gave off a strong odor of camphor, and inside were neatly folded embroidered sheets, some blankets, and a quilt.

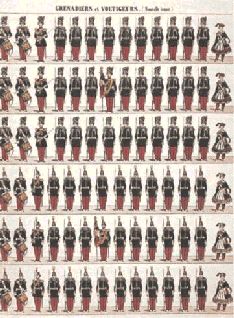

I walked back down the hall toward the antechamber and then started down the left-hand side. On these walls were German prints, very finely worked, Zur Geschichte der Kostüme: splendid Bornean women, beautiful Javanese, Chinese mandarins, Slavs from Sibenik with pipes as long as their mustaches, Neapolitan fishermen and Roman brigands with blunderbusses, Spaniards in Segovia and Alicante… And also historical costumes: Byzantine emperors, popes and knights of the feudal era, Templars, fourteenth-century ladies, Jewish merchants, royal musketeers, uhlans, Napoleonic grenadiers. The German engraver had captured each subject dressed for a great occasion, so that not only did the high and mighty pose weighed down by jewels, armed with pistols with decorated stocks, or decked out in parade armor or sumptuous dalmatics, but even the poorest African, the lowest commoner, appeared in colorful scarves that hung to their waists, mantles, feathered hats, rainbow turbans.

It may be that before reading many adventure books I explored the polychromatic multiplicity of the races and peoples of the earth in these prints, hung with their frames almost touching, many of them now faded from years and years of the sunlight that had rendered them, in my eyes, epiphanies of the exotic. "Races and peoples of the earth," I repeated aloud, and a hairy vulva came to mind. Why?

The first door belonged to a dining room, which also communicated with the antechamber. Two faux fifteenth-century sideboards, the doors of which were inset with circular and lozenge-shaped panes of colored glass, a few Savonarola-style chairs like something out of The Jester’s Supper, and a wrought-iron chandelier rising above the grand table. I whispered to myself, "capon and royal soup," but I did not know why. Later I asked Amalia why there should be capon and royal soup on the table, and what royal soup was. She explained to me that at Christmastime, each year our Good Lord granted us on this earth, Christmas dinner consisted of capon with sweet and spicy relishes, and before that the royal soup: a bowl of capon broth full of little yellow balls that melted in your mouth.

"Royal soup was so good, such a crime they don’t make it anymore, I reckon because they sent the king packing, poor man, and I’d like a word or two with Il Duce about that!"

"Amalia, Il Duce isn’t around anymore, even people who’ve lost their memories know that."

"I’ve never been much on politics, but I know they sent him off once and he came back. I’m telling you, that fellow is off biding his time somewhere, and one day, well, you never know… But be that as it may, your good grandfather, may God rest his soul in glory, was partial to capon and royal soup, it wasn’t Christmas without them."

Capon and royal soup. Had the shape of the table brought them to mind? Or the chandelier that must have illuminated them each December? I did not remember the taste of the soup, just the name. It was like that word game called Target: table gives rise to chair or dining or wine. For me, it called to mind royal soup, purely through word association.

I opened another door. I saw a double bed, and I hesitated a moment before entering the room, as though it were off limits. The silhouettes of furniture loomed large in the shadows, and the four-poster bed, its canopy intact, seemed like an altar. Could it have been my grandfather’s bedroom, which I had not been allowed to enter? Had he died there, done in by grief? And had I been there to say my last good-byes?

The next room was also a bedroom, with furnishings from an indeterminate epoch, pseudo-Baroque. No right angles, everything curved, including the doors of the great wardrobe, with its mirror and chest of drawers. I suddenly felt a knot in my pylorus, as I had in the hospital when I saw the photo of my parents on the day of their honeymoon. The mysterious flame. When I had tried to describe the feeling to Dr. Gratarolo, he had asked me if it was like an extrasystole. Perhaps, I said, but accompanied by a warmth that rises in my throat… In that case, no, Gratarolo had said, extrasystoles are not like that.

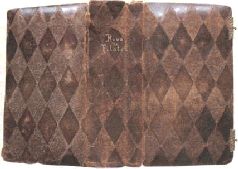

It was in this room that I caught sight of a book, a small one, bound in brown leather, on the marble surface of the right-hand bedside table, and I went straight to it and opened it, saying to myself riva la filotea. In the Piedmontese dialect riva means "arrives"… but what was arriving? I sensed that this mystery had been with me for years, with its question in dialect (but did I speak dialect?): La riva? Sa ca l’è c’la riva? Something is arriving, but what is a filotea? A filobus, a trolley car, a tram of some kind?

I opened the book-which felt like a sacrilegious act-and it was La Filotea, by the Milanese priest Giuseppe Riva, an 1888 anthology of prayers and pious meditations, with a list of feast days and a calendar of the saints. The book was falling apart, and the pages cracked beneath my fingers when I touched them. I put it back together with religious care (part of my job, after all, is taking care of old books), and as I did I saw the spine, on which was printed, in faded gilt letters, RIVA LA FILOTEA. It must have been someone’s prayer book, which I had never dared to open, but which, with the ambiguous wording on its spine that failed to distinguish between author and title, had seemed to herald the imminent arrival of some disquieting streetcar, which might have been named Desire.

Then I turned, and I saw that on the curved sides of the dresser were two smaller doors: with a quickening pulse, I hurried over and opened the one on the right, meanwhile looking around as though I were afraid of being observed. There were three shelves inside, curved too, but empty. I felt distressed, as if I had committed a theft. An ancient theft, perhaps: I must have snooped around in those drawers; perhaps they once contained something I was not supposed to touch, or see, and so I did it on the sly. By this time I was certain, reasoning almost like a detective: this had been my parents’ bedroom, La Filotea was my mother’s prayer book, and I used to go to those hiding places in the dresser in order to lay my hands on something intimate-old correspondence, perhaps, a billfold, packets of photographs that could not be put in the family album…

But if this was my parents’ bedroom, and if I was born in Solara, as Paola said, then this room was where I had come into the world. Not to recall the room where one was born is normal. But if for years people have pointed to a place and told you, That is where you were born, on that big bed, a place where you sometimes insisted that you be allowed to spend the night between papà and mamma, where who knows how often, already weaned, you tried to smell again the scent of the breast that suckled you-all that should have left at least a trace in these damn lobes of mine. But no, even here my body retained only the memory of certain oft repeated gestures, that was all. In other words, if I wanted I could instinctively repeat the sucking motion of a mouth on a nipple, but nothing more; I could not tell you whose breast it was or what the taste of the milk was like.

Is it worth it to be born if you cannot remember it later? And, technically speaking, had I ever been born? Other people, of course, said that I was. As far as I know, I was born in late April, at sixty years of age, in a hospital room.

Signor Pipino, born an old man and died a bambino. What story was that? Signor Pipino is born in a cabbage at sixty years of age, with a nice white beard, and over the course of his adventures he grows a little younger each day, till he becomes a boy again, then a nursling, and then is extinguished as he unleashes his first (or last) scream. I must have read that story in one of my childhood books. No, impossible, I would have forgotten it like the rest, I must have seen it quoted when I was forty, say, in a history of children’s literature-did I not know more about George Washington’s cherry tree than my own fig trees?

In any case, I had to begin the recovery of my personal history there, in the shadows of those corridors, so that if I was going to die in swaddling bands at least I would be able to see my mother’s face. My God, though, what if I expired with some blubbery, bewhiskered midwife looming over me?

At the end of the hallway, past a settle beneath the last window, were two doors, one on the end wall and one on the left. I opened the one on the left and entered a spacious study, aquarial and severe. A mahogany table dominated by a green lamp, like those in the Biblioteca Nazionale, was illuminated by two windows with panes of colored glass that opened out on the side of the left wing, onto perhaps the quietest, most private area of the house, offering a superb view. Between the two windows, a portrait of an elderly man with a white mustache, posing as if for a rustic Nadar. The photo could not possibly have been there when my grandfather was still alive, a normal person does not keep his own portrait in front of his eyes. My parents could not have put it there, since he died after they did, indeed as a result of his grief over their passing. Perhaps my aunt or uncle, after selling the city house and the land around this house, had redone this room as a kind of cenotaph. And in fact nothing testified that it had been a place of work, an inhabited space. Its sobriety was deathly.

On the walls, another series from the Imagerie d’Épinal, with lots of little soldiers in blue and red uniforms: Infantry, Cuirassiers, Dragoons, Zouaves.

I was struck by the bookcases, which, like the table, were mahogany: they covered three walls but were practically empty. Two or three books had been placed on each shelf, for decoration-exactly what bad designers do to provide their clients with a bogus cultural pedigree while leaving space for Lalique vases, African fetishes, silver plates, and crystal decanters. But these shelves lacked all such expensive trinkets: just a few old atlases, a set of glossy French magazines, the 1905 edition of the Nuovissimo Melzi encyclopedia, and French, English, German, and Spanish dictionaries. It was unthinkable that my grandfather, a seller and collector of books, had spent his life next to empty bookcases. And indeed, up on one shelf, in a silver-plated frame, I found a photograph, evidently taken from one corner of the room as sunlight from the windows shone on the desk:

Grandfather was seated, looking surprised, in shirtsleeves (but with a vest), barely fitting between two heaps of papers that cluttered the table. Behind him, the shelves were crowded with books, and among the books rose piles of newspapers, stacked sloppily. In the corner, on the floor, other heaps could be glimpsed, perhaps magazines, and boxes full of other papers that looked as though they had been tossed there to save them from being tossed out. Now that was what my grandfather’s room must have been like when he was alive, the warehouse of one who hoarded all manner of printed matter that others would have thrown in the trash, the hold of a ghost ship transporting forgotten documents from one sea to another, a place in which to lose oneself, to plunge into those untidy tides of paper. Where had all those marvels gone? Well-meaning vandals had apparently whisked away everything that could be seen as messy, all of it. Sold perhaps at some wretched junk shop? Perhaps it was after such a spring cleaning that I decided not to visit these rooms anymore, tried to forget Solara? And yet I must have spent hour after hour, year after year, in that room with my grandfather, discovering with him who knows what wonders. Had even this last handhold on my past been taken from me?

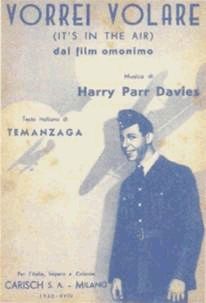

I went out of the studio and into the room at the end of the hall, which was much smaller and less austere: light-colored furniture, made perhaps by a local carpenter, in a simple style, sufficient no doubt for a boy. A small bed in a corner, a number of shelves, virtually empty except for a row of nice red hardbacks. On a little student desk, neatly arranged with a black book bag in the center and another green lamp, lay a worn copy of Campanini Carboni, the Latin dictionary. On one wall, attached with two tacks, an image that caused me to feel another very mysterious flame. It was the cover of a songbook, or an ad for a record, It’s in the Air, but I knew it came from a film. I recognized George Formby with his horsey smile, I knew he sang while playing his ukulele, and now I was seeing him again, riding an out-of-control motorcycle into a haystack and coming out the other side amid a din of chickens, as the colonel in the sidecar catches an egg that falls into his hand, and then I saw Formby spiraling downward in an old-style plane he had got into by mistake, but he righted himself, then rose and fell again in a nosedive- oh, how funny, I was dying of laughter, "I saw it three times, I saw it three times," I was nearly yelling. "The funniest picture show I ever saw," I kept repeating, saying picture show, as we apparently did in those days, at least in the country.

That was certainly my room, my bed and desk, but except for those few items it was bare, as if it were the great poet’s room in the house of his birth: a donation at the door and a mise-en-scène designed to exude the scent of an inevitable eternity. This is where he composed August Song, Ode for Thermopylae, The Dying Boat-man’s Elegy… And where is he now, the Great One? No longer with us, consumption carried him away at the age of twenty-three, on this very bed, and notice the piano, still open just as He left it on his last day upon this earth, do you see? The middle A still shows traces of the spot of blood that fell from his pale lips as he was playing the Water Drop Prelude. This room is merely a reminder of his brief sojourn on this earth, hunched over sweat-drenched pages. And the pages? Those are locked away in the Biblioteca del Collegio Romano and can be seen only with the grandfather’s consent. And the grandfather? He is dead.

Furious, I went back into the hallway, leaned out the window that looked out on the courtyard, and called Amalia. How can it be, I asked her, that there are no more books or anything else in these rooms? Why are my old toys not in my bedroom?

"Signorino Yambo, that was still your room when you was sixteen, seventeen years old. What would you have been wanting with toys then? And why worry your head about them fifty years later?"

"Never mind. But what about Grandfather’s study? It must have been full of stuff. Where did that end up?"

"Up in the attic, it’s all in the attic. Remember the attic? It’s like a cemetery, breaks my heart just to go in, and I only go to set out the saucers of milk. Why? Well that’s how I put the three cats in a mind to go up there, and once they get there they have fun hunting the mice. One of your grandfather’s notions: Lots of papers up in the attic, got to keep the mice away, and you know in the country no matter how hard you try… As you got bigger, your old things would end up in the attic, like your sister’s dolls. And later, when your aunt and uncle got their hands on the place, well, I don’t mean to criticize, but they could at least have left out what was out. But no, it was like housecleaning for the holidays. Everything up to the attic. So of course that floor you’re on now turned into a morgue, and when you came back with Signora Paola nobody wanted to bother with it and that’s why you all went to stay in the other wing, which it’s not as nice but easier to keep clean, and Signora Paola got it fixed up real good…"

If I had been expecting the main wing to be the cave of Ali Baba, with its amphorae full of gold coins and walnut-sized diamonds, with its flying carpets cleared for takeoff, we had completely miscalculated, Paola and I. The treasure rooms were empty. Did I need to go up into the attic and bring whatever I discovered back down, so I could return the rooms to their original state? Sure, but I would have to remember what their original state had been, and that state was precisely what I needed to spur my memory.

I went back to my grandfather’s study and noticed a record player on a little table. Not an old gramophone, but a record player, with a built-in case. It must have been from the fifties, judging by the design, and only for 78s. So my grandfather listened to records. Had he collected them, as he collected everything else? If so, where were they now? In the attic, too?

I began to flip through the French magazines. They were deluxe magazines with a flowery, nouveau aesthetic and pages that looked illuminated, with illustrated margins and colorful Pre-Raphaelite images of pallid damsels in colloquy with knights of the Holy Grail. And there were stories and articles, these too in frames with lily scrolls, and fashion pages, already in the art deco style, featuring wispy ladies with bobs, chiffon or embroidered silk dresses with low waists, bare necks, and plunging backs, lips as blood-red as wounds, wide mouths from which to draw out lazy spirals of bluish smoke, little hats with veils. These minor artists knew how to draw the scent of powder puffs.

The magazines alternated between a nostalgic return to art nouveau, which had just gone out of fashion, and an exploration of what was currently in vogue, and perhaps that backward glance at charms that were ever so slightly outmoded lent a patina of nobility to their plans for the Future Eve. But it was over an Eve who was, apparently, slightly passé that I paused with a fluttering heart. It was not the mysterious flame, it was actual tachycardia this time, a flutter of nostalgia for the present.

It was the profile of a woman with long golden hair and something of the fallen angel about her. I recited silently:

Long-stemmed lilies, pale, devout, were dying in your bands, candles gone cold. Their perfume slipping through your fingers’ hold was the last gasp of great pain snuffing out. And your bright clothes gave off the life breath of both agony and love.

My God, I must have seen that profile before, as a child, as a boy, as an adolescent, perhaps again on the threshold of adulthood, and it had been stamped on my heart. It was Sibilla’s profile. I had known Sibilla, then, from time immemorial; a month ago in my studio I had simply recognized her. But this realization, rather than gratifying me and moving me to renewed tenderness, now withered my spirit. Because in that moment I realized that, seeing Sibilla, I had simply brought a childhood cameo back to life. Perhaps I had already done that, when we first met: I thought of her at once as a love object, because that image had been a love object. Later, when I met her again after my reawakening, I imagined an affair between us that was nothing more than something I had longed for in the days when I wore short pants. Was there nothing between myself and Sibilla but this profile?

And what if there were nothing but that face between me and all the women I have known? What if I have never done anything but follow a face I had seen in my grandfather’s study? Suddenly the project I was undertaking in those rooms took on a new valence. It was no longer simply an attempt to remember what I had been before I left Solara, but also an investigation of why I had done what I had done after Solara. But was that really what happened? Don’t exaggerate, I told myself, so you saw an image that reminds you of a woman you just met. Maybe for you this figure suggests Sibilla simply because she is slender and blond, but for someone else she might call to mind, who knows, Greta Garbo, or the girl next door. You are simply still obsessed, and like the guy in the joke (Gianni had told it to me when I was telling him about the hospital tests), you always see the same thing in every inkblot the doctor shows you.

So, here you are looking for your grandfather, and your mind is on Sibilla?

Enough with the magazines, I would look at them later. I was suddenly drawn to the Nuovissimo Melzi, 1905 edition, 4,260 plates, seventy-eight tables of illustrated nomenclature, 1,050 portraits, twelve chromolithographs, Antonio Vallardi publisher, Milan. As soon as I opened it, at the sight of those yellowed pages in 8-point type and the little illustrations at the beginning of the most important entries, I immediately went to look for what I knew I would find. The tortures, the tortures. And indeed, there they were, the page with various types of tortures: boiling, crucifixion, the equuleus (with the victim hoisted and then dropped buttocks-first onto a cushion of whetted iron spikes), fire (where the soles of the feet are roasted), the gridiron, live burial, pyres, burnings at the stake, the wheel, flaying, the spit, the saw (hideous parody of a magic show, with the victim in a box and two executioners with a great toothed blade, except that the subject actually ended up in two pieces), quartering (much like the previous one, except that here a lever-like blade must have presumably divided the unfortunate one lengthwise as well), then dragging (with the guilty party tied to a horse’s tail), foot screws, and, most impressive of all, impaling (and at that time I would have known nothing of the forests of burning impalees by the light of which Voivode Dracula dined), and on it went, thirty types of torture, each more gruesome than the last.

The tortures… Had I closed my eyes immediately after coming to that page, I could have named them one by one, and the bland horror, the mute exaltation I was feeling, were my own, in that moment, not those of someone else I no longer knew.

How long I must have lingered over that page. And how long, too, over other pages, some in color, to which I turned without relying on alphabetical order, as if I were following the memory of my fingertips: mushrooms, fleshy ones, the most beautiful among them poisonous- the fly agaric with its red cap flecked with white, the noxious yellow bleeding milk cap, the smooth parasol, Satan’s bolete, the sickener like a fleshy mouth opened in a grimace; then fossils, with the megathere, the mastodon, and the moa; ancient instruments (the ramsinga, the oliphant, the Roman bugle, the lute, the rebec, the aeolian harp, Solomon’s harp); the flags of the world (with countries named Cochin China, Anam, Baluchistan, Malabar,

Tripoli, Congo Free State, Orange Free State, New Granada, the Sandwich Islands, Bessarabia, Wallachia, Moldavia); vehicles, such as the omnibus, the phaeton, the hackney, the landau, the coupé, the cabriolet, the sulky, the stagecoach, the Etruscan chariot, the Roman biga, the elephant tower, the carroche, the berlin, the palanquin, the litter, the sleigh, the curricle, and the oxcart; sailing ships (and I had thought some sea-adventure tale had taught me such terms as brig-antine, mizzen sail, mizzen topsail, mizzen-topgallant sail, crow’s nest, mainmast, foremast, foretopmast, fore-topgallant sail, jib and flying jib, boom, gaff, bowsprit, top, broadside, luff the mainsail you scurvy boatswain, hell’s bells and buckets of blood, shiver my timbers, take in the topgallants, man the port broadside, Brethren of the Coast!); on to ancient weaponry-the hinged mace, the scourge, the executioner’s broadsword, the scimitar, the three-bladed dagger, the dirk, the halberd, the wheel-lock harquebus, the bombard, the battering ram, the catapult; and the grammar of heraldry: field, fess, pale, bend, bar, per pale, per fess, per bend, quarterly, gyronny… This had been the first encyclopedia in my life, and I must have pored over it at great length. The margins of the pages were badly worn, many entries were underlined, and sometimes there appeared beside them quick annotations in a childish hand, usually transcriptions of difficult terms. This volume had been used nearly to death, read and reread and creased, and many pages were now coming loose.

Was this where my early knowledge had been shaped? I hope not; I sneered at the sight of certain entries, particularly those most underlined:

Plato. Emin. Gr. phil, greatest of ancient phils. Disciple of Socrates, whose doctrine he espoused in the Dialogues. Assembled fine collection of antiques. 429-347 B.C.

Baudelaire. Parisian poet, peculiar and artificial in his art.

Apparently one can overcome even a bad education. Later I grew older and wiser, and at college I read nearly all of Plato. Nowhere did I ever find evidence that he had put together a fine collection of antiques. But what if it were true? And what if it had been, for him, the most important thing, and the rest was a way to make a living and allow himself that luxury? As for the tortures, they no doubt existed, though I do not believe that the history books used in schools have much to say about them, which is too bad-we really should know what stuff we are made of, we children of Cain. Did I, then, grow up believing that man was irremediably evil and life a tale full of sound and fury? Was that why I would, according to Paola, shrug my shoulders when a million babies died in Africa? Was it the Nuovissimo Melzi that gave rise to my doubts about human nature? I continued to leaf through its pages:

Schumann (Rob.). Celeb. Ger. comp. Wrote Paradise and the Peri, many Symphonies, Cantatas, etc. 1810-1856.-(Clara). Distinguished pianist, widow of preced. 1819-1896.

Why "widow"? In 1905 they had both been dead for some time. Would we describe Calpurnia as Julius Caesar’s widow? No, she was his wife, even if she survived him. Why then was Clara a widow? My goodness, the Nuovissimo Melzi was also susceptible to gossip: after the death of her husband, and perhaps even before, Clara had had a relationship with Brahms. The dates are there (the Melzi, like the oracle of Delphi, neither reveals nor conceals; it indicates), Robert died when she was only thirty-seven, with forty more years ahead of her. What should a beautiful, distinguished pianist have done at that age? Clara belongs to history as a widow, and the Melzi was recording that. But how had I come to learn Clara’s story? Perhaps the Melzi had piqued my curiosity about that "widow." How many words do I know because I learned them there? Why do I know even now, with adamantine certainty, and in spite of the tempest in my brain, that the capital of Madagascar is Antananarivo? It was in that book that I had encountered terms that tasted like magic words: avolate, baccivorous, benzoin, cacodoxy, cerastes, cribble, dogmatics, glaver, grangerism, inadequation, lordkin, mulct, pasigraphy, postern, pulicious, sparble, speight, vespillo, Adrastus, Allobroges, Assur-Bani-Pal, Dongola, Kafiristan, Philopator, Richerus…

I leafed through the atlases: some were quite old, from before the First World War, when Germany still had African colonies, marked in bluish gray. I must have looked through a lot of atlases in my life-had I not just sold an Ortelius? But some of these exotic names had a familiar ring, as if I needed to start from these maps in order to recover others. What was it that linked my childhood to German West Africa, to the Dutch West Indies, and above all to Zanzibar? In any case, it was undeniable that there in Solara every word gave rise to another. Would I be able to climb back up that chain to the final word? What would it be? "I"?

I had gone back to my room. I felt absolutely sure about one thing. The Campanini Carboni did not include the word "shit." How do you say that in Latin? What did Nero shout when, hanging a painting, he smashed his thumb with the hammer? Qualis artifex pereo? When I was a boy, those must have been serious questions, and official culture offered no answers. In such cases one turned to nonscholastic dictionaries, I imagined. And indeed the Melzi records shit, shite, shitten, shitty… Then like a flash I heard a voice: "The dictionary at my house says that a pitana is a woman who sells by herself." Someone, a schoolmate, had flushed out from some other dictionary something not found even in the Melzi; he pronounced the forbidden word in a kind of semidialect (the dialect form was pütan’na), and I must have long been fascinated by that phrase "sells by herself." What could be so forbidden about selling, as it were, without a clerk or bookkeeper? Of course, the word in his prim dictionary must have been puttana, whore, a woman who sells herself, but my informer had mentally translated that into the only thing he thought might have some malicious implication, the sort of thing he might hear around the house: "Oh, she’s a wily one, she does all her selling by herself…"

Did I see anything again-the place, the boy? No, it was as though phrases were resurfacing, sequences of words, written about a story I once had read. Flatus vocis.

The hardbacks could not have been mine. I must have taken them from my grandfather, or maybe my aunt and uncle had moved them here from my grandfather’s study, for decorative reasons. Most of them were cartonnés from the Collection Hetzel, the complete works of Verne, red bindings with gilt ornaments, multicolored covers with gold decorations… Perhaps I had learned my French through these books, and once again I turned confidently to the most memorable images: Captain Nemo looking through the porthole of the Nautilus at the gigantic octopus, the airship of Robur the Conqueror abristle with its high-tech yards, the hot-air balloon crash-landing on the Mysterious Island ("Are we rising again?" "No! On the contrary! We’re descending!" "Worse than that, Mr. Cyrus! We’re falling!"), the enormous projectile aimed at the moon, the caverns at the center of the earth, the stubborn Kéraban, and Michel Strogoff… Who knows how much those figures had unsettled me, always emerging from dark backgrounds, outlined by thin black strokes alternating with whitish gashes, a universe void of solid chromatic zones, a vision made of scratches, or streaks, of reflections dazzling for their lack of marks, a world viewed by an animal with a retina all its own-maybe the world does look like that to oxen or dogs, to lizards. A ruthless nightworld seen through ultrathin Venetian blinds. Through these engravings, I entered the chiaroscuro world of make-believe: I lifted my eyes from the book, emerged from it, was wounded by the full sun, then went back down again, like a submarine sinking to depths at which no color can be distinguished. Had they made any Verne books into color movies? What does Verne become without those engravings, those abrasions that generate light only there where the graver’s tool has hollowed out the surface or left it in relief?

My grandfather had had other volumes bound, though he kept the old illustrated covers: The Adventures of a Parisian Lad, The Count of Monte Cristo, The Three Musketeers, and other masterpieces of popular romanticism.

There were two versions of Jacolliot’s Les ravageurs de la mer, the French original and Sonzogno’s Italian edition, retitled Captain Satan. The engravings were the same, who knows which I had read. I knew there were two terrifying scenes: first the evil Nadod cleaves the good Harald’s head with a single hatchet blow and kills his son Olaus; then at the end Guttor the executioner grasps Nadod’s head and begins squeezing it by degrees between his powerful hands, until the wretch’s brains spurt straight up to the ceiling. In the illustration of that scene, the eyes of both victim and executioner are bulging nearly out of their sockets.

Most of the action takes place on icy seas covered by hyperborean mist. In the engravings, foggy, mother-of-pearl skies contrast "With the whiteness of the ice. A wall of gray vapor, a milky hue more evident than ever… A fine white powder, resembling ashes, falling over the canoe… From the depths of the ocean a luminous glare arose, an unreal light… A downpour of white ashy powder, with momentary rents within which one glimpsed a chaos of indistinct forms… And a human figure, infinitely larger in its proportions than any dweller among men, wrapped in a shroud, its face the immaculate whiteness of snow… No, what am I saying, these are memories of another story. Congratulations, Yambo, you have a fine short-term memory: were these not the first images, or the first words, that you remembered as you were waking in the hospital? It must be Poe. But if these lines by Poe are so deeply etched in your public memory, might that not be because when you were small you had these private visions of the pallid seas of Captain Satan?

I stayed there reading (rereading?) that book until evening. I know that I was standing when I began, but I ended up sitting with my back against the wall, the book on my knees, forgetful of time, until Amalia came to wake me from my trance, shouting, "You’ll ruin your eyes like that, your poor mother tried to teach you! My goodness gracious, you didn’t set foot outside today, and it was the prettiest afternoon a body could ask for. You didn’t even come see me for lunch. Come on, let’s go, time for supper!"

So I had repeated an old ritual. I was worn out. I ate like a boy at the height of a growth spurt, then was overcome by drowsiness. Usually, according to Paola, I read for a long time before falling asleep, but that night, no books, as if on Mother’s orders.

I dozed off at once, and I dreamed of the lands of the South Seas, made of streaks of cream arranged in long strands across a plate of mulberry jam.